Abstract

Azithromycin is effective at controlling exaggerated inflammation and slowing the long-term decline of lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis. We previously demonstrated that the drug shifts macrophage polarization towards an alternative, anti-inflammatory phenotype. Here we investigated the immunomodulatory mechanism of azithromycin through its alteration of signaling via the NF-κB and STAT1 pathways. J774 murine macrophages were plated, polarized (with IFNγ, IL4/13, or with azithromycin plus IFNγ), and stimulated with LPS. The effect of azithromycin on NF-κB and STAT1 signaling mediators was assessed by Western blot, HTRF assay, nuclear translocation assay, and immunofluorescence. The drug’s effect on gene and protein expression of arginase was evaluated as a marker of alternative macrophage activation. Azithromycin blocked NF-κB activation by decreasing p65 nuclear translocation while blunting the degradation of IκBα due at least in part to a decrease in IKKβ kinase activity. A direct correlation was observed between increasing azithromycin concentrations and increased IKKβ protein expression. Moreover, incubation with the IKKβ inhibitor IKK16 decreased arginase expression and activity in azithromycin-treated cells, but not in cells treated with IL4 and IL13. Importantly, azithromycin treatment also decreased STAT1 phosphorylation in a concentration-dependent manner, an effect that was reversed with IKK16 treatment. We conclude that AZM anti-inflammatory mechanisms involve inhibition of the STAT1 and NF-κB signaling pathways through the drug’s effect on p65 nuclear translocation and IKKβ.

Introduction

While the function of alternatively activated macrophages (M2-polarized) has primarily been evaluated in host responses to disease processes that elicit Th2-type immune mechanisms (1–4), little is known of their role in regulating inflammation in response to extracellular Gram-negative bacterial infections. M2-polarized macrophages primarily function to orchestrate remodeling and repair by producing effector molecules such as arginase-1 and TGFβ. In the cystic fibrosis lung, these mediators control lung homeostasis, inflammation, and subsequent pulmonary damage associated with pneumonia (4, 5). We have demonstrated that the antimicrobial azalide azithromycin can induce macrophage characteristics that are consistent with M2 polarization, both in vitro and in a mouse model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia (6–8). The subsequent improvement observed in the severity of lung destruction and in the mortality of this infection model has direct bearing on chronic inflammatory lung conditions such as cystic fibrosis, where P. aeruginosa relapsing pneumonias contribute to the decline in pulmonary function over time (9, 10).

Macrophages are polarized to distinct functional phenotypes via signaling through two separate pathways (11–13). Classical, or M1 macrophages are activated by TNFα or IFN-γ when stimulated by non-self foreign antigens (such as LPS in the case of gram-negative bacteria) (14, 15). Signaling through IRF and STAT is the central governing mechanism of macrophage M1-M2 polarization (14–16). LPS signaling through the pattern recognition receptor TLR4 activates several signaling cascades which involve two adaptors, MyD88 and TRIF. MyD88 signaling activates the nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB), the main M1 macrophage transcription factor (14, 15). Alternatively, TRIF signaling promotes the secretion of type I interferons through IRF3 activation. Consequently, secreted interferons bind receptors on macrophages and stimulate the phosphorylation and activation of the second M1 transcription factor, STAT-1. Phosphorylated STAT-1 subunits form dimers and translocate to the nucleus (15), inducing the transcription of many inflammatory mediators and cytokines (12, 17).

Similarly, NF-κB activation involves a series of phosphorylation steps which result in its translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Canonical NF-κB is the prototypical pro-inflammatory transcription factor activated through TLR and inflammatory cytokine signaling. In the absence of TLR and cytokine receptor stimulants, NF-κB activation is suppressed by an inhibitory subunit (IκBα, IκBβ, or IκBɛ) which binds to dimerized NF-κB subunits (p50 or RelA (also named p65)) and prevents them from translocating to their site of action in the nucleus. Therefore, stimulation through TLR, IL1R, or other TNF receptor family members results in a series of phosphorylation reactions activating the IKK complex (a trimeric complex composed of two catalytic subunits, IKKα and IKKβ, and a regulatory subunit, IKKγ) (18, 19). Activated IKKβ phosphorylates the NF-κB inhibitory subunit, IκBα. Once phosphorylated, the IκBα subunits undergo rapid ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thus releasing p50/p65 from the inhibited state. Dimerized subunits then translocate to the nucleus where they bind to the NF-κB DNA promoter region, thereby controlling several genes for pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, iNOS, and IFNγ (20–24). Regulation of NF-κB activation mainly involves tight control of the activity and synthesis of the IκBα and IKKβ proteins (sensitive to NF-κB activation through negative feedback regulation) as well as controlling subunit nuclear translocation and DNA binding (19). Additionally, IKKβ activation requires phosphorylation of two serines; thus, regulation of IKKβ activation involves tight control of its trans-autophosphorylation as well as its phosphorylation by the upstream kinases (19, 21, 22).

Alternative, or M2 macrophage polarization, occurs through the binding of either IL-4 or IL-13 to their respective receptors leading to the phosphorylation and dimerization of STAT-6. Upon activation, STAT-6 translocates to the nucleus and upregulates the expression of genes associated with anti-inflammatory processes (25–29). Through our work characterizing the effects of azithromycin, we found that the drug is only able to polarize macrophages to an M2-like phenotype when they are also stimulated with LPS (27). This characteristic provides the basis for our hypothesis that the mechanism of the drug’s ability to polarize cells lies in its interference with these signaling cascades. Others have shown that azithromycin decreases the activation of NF-κB signaling and subsequent production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory effectors (30, 31). While these effects alone may help to explain the beneficial effects of azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis, the mechanism by which azithromycin is able to polarize macrophages towards an M2-like phenotype is unknown.

In the present study we investigate the hypothesis that azithromycin polarizes macrophages to an M2 phenotype via inhibition of STAT-1 and NF-κB signaling mediators. We demonstrate that azithromycin inhibits the nuclear translocation of p65, and this correlated with concurrent increased amounts of IKKβ. Additionally, STAT-1 phosphorylation was inhibited by the drug. The addition of an IKKβ competitive inhibitor resulted in a reversal of production of the alternatively activated macrophage effector arginase-1. These results provide insights into the immunomodulatory mechanism of azithromycin and support studies by others that demonstrate an interface between the 2 pathways through IKKβ.

Materials and Methods

Macrophage polarization

In-vitro assays used to study azithromycin’s mechanism of action were performed using the murine macrophage cell line J774A.1 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) as well as using primary bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs). J774 macrophages were allowed to grow and reach confluency using DMEM + 10% FBS + 1% sodium pyruvate + 1% penicillin/streptomycin in all experiments. Confluent cells were scrapped, counted, and plated in 24-well plates at a concentration of 2.5×105 cells per 1ml of media. Cells were allowed to adhere for 4–8 hours and then polarized to an M1 phenotype with IFNγ (final concentration 20 ng/ml) or to an M2 phenotype with both IL-4 and IL-13 (final concentration 10 ng/ml of each). Azithromycin was added to select wells along with IFNγ at concentrations ranging from 5 to 100 μM. Additionally, IKK-16, an IKKβ inhibitor, was added to select wells with azithromycin and IFNγ (final concentrations 50 or 100 nM). Cells were then incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Polarized cells were then stimulated with LPS (final concentration 100 ng/ml). The duration of LPS stimulation ranged from 0 to 60 minutes or up to 24 hours depending on the experimental goals. Cells were then washed, harvested by scraping, enumerated, and lysed in 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100 (protease and phosphatase inhibitors were added to the lysis buffer prior to use). Protein concentrations were quantified utilizing the Pierce BCA reaction kit. Alternatively, in some experiments cells were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic contents or homogenized with Trizol for RNA extraction. Additionally, bone marrow cells isolated from the femur and tibia bones of sacrificied C57BL/6 mice were cultured for 6 days in RPMI supplemeted with L929 suppernatant containing M-CSF. After 6 days, BMDMs were plated at 2.5× 105 cells/ml in a 24-well plate. Cells were allowed to adhere for 8 hours and then polarized to an M1 phenotype or to an M2 phenotype as described above.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA isolation was performed using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNeasy Mini Kits (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) per manufacturers instructions. Isolated RNA was quantified using Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Equal amounts of RNA were then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocols. cDNA samples were then used for quantitative real-time PCR using the TaqMan gene expression arrays for murine Arg1 (arginase-1), Ikbkb (IKKβ) and GAPDH. An epMotion 5070 robot was used to accurately pipette the PCR reaction components (cDNA template, forwards and reverse primers, TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, and RNase-free water) into 384-well plates. Plates were centrifuged briefly and transferred into the ABI Prism 7900HT Fast Real Time-PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) set for 40 standard thermal PCR cycles. The generated CT values were used to quantify gene expression. ΔCt values were calculated by normalizing the target gene expression (Arg1 and Ikbkb) to the housekeeping gene expression (GAPDH). The ΔΔCt was then calculated by comparing the expression of the experimental condition to the control condition. Power analysis of the generated ΔΔCt values was then used to interpret the fold change in gene expression.

RelA translocation assay

A nuclear translocation assay was used to interpret NF-κB activation by quantifying the amount of translocated p65 subunit (RelA) in the nucleus compared to that remaining in the cytoplasm. Polarized and stimulated J774 macrophages were counted and fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions using the NF-κB Assay Kit (FivePhoton Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer protocol. Supernatants containing the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were collected, and p65 was quantified in each by Western blot.

Immunofluorescence staining and analysis

Immunostaining was used to visualize the NF-κB subunit localization in stimulated cells. Macrophages were polarized as described except that round glass coverslips (12 mm) were added to each well of the 24-well plates. Cells were allowed to attach to the glass coverslips overnight. After polarization and stimulation, the coverslips were washed three times with PBS++ (PBS contianing 0.5 mM CaCl2 and MgCl2). Cells were then fixed and permeabilized by with ice-cold methanol. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted at appropriate concentrations in 3% BSA as determined by titration experiments, and each was applied to the coverslips sequentially for 45 minute incubations in a humidified chamber. The coverslips were finally incubated in DAPI nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), washed, and mounted using an antifade reagent. Stained cells were visualized using a Zeiss fluorescent microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) with a 100X objective. Multiple fields were evaluated to score at least 150 cells per replicate coverslip by 2 blinded investigators. Each cell was evaluated to determine the localization of the p65 signal with respect to the nucleus as follows: p65 signal in cytoplasm only (score 0), evenly distributed between the nucleus and cytoplasm (score 1), mostly nuclear with faint cytoplasmic signal (score 2), or nuclear signal only (score 3). Scores were then averaged and compared to the control condition.

Arginase assay

Arginase enzymatic activity was assessed using the urea-based assay. Arginase is an enzyme which metabolizes arginine into ornithine and urea; therefore, urea concentrations directly correlate with the activity and expression level of arginase. J774 murine macrophages were polarized and lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 (containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors) as described. The enzyme was activated by incubating 50 μL of the cell lysate with 50 μL of the arginase activation solution (10 mM MnCl2 in 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5) for 10 minutes at 55 °C. Subsequently, 25 μL of the mixture was added to 25 μL of the arginase substrate solution (0.5 M L-arginine in water, pH 9.7) and incubated at 37 °C for 6 hours. The reaction was then terminated by adding an acid mixture (H2SO4, H3PO4, water at a ratio of 1:3:7), followed by the addition of 25 μL of alpha-isonitrosopropiophenone (9% w/v) which was heated to 100°C for 45 minutes. Optical density was then read at 540 nm wavelength using a spectrophotometer (the intensity of color change of the urea-chromogen complex was measured). A standard curve was used to interpret the results by repeating the assay described above using standard stock solutions with known urea concentrations. Readings were normalized to the optical density of blank sample and water, and normalized to total protein concentration of each sample.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to determine the effect of macrophage polarization on the protein mediators of NF-κB and Stat1 signaling pathways. Cell lysates obtained from the polarization assay described above were quantified. Samples of 20–30 μg of protein were denatured in loading buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) containing β-mercaptoethanol. Denatured samples were loaded onto 4–15% precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were then separated by electrophoresis at 100 V for 1–2 hours and transferred onto a methanol-activated and wetted Immobilon®-FL PVDF membranes at 100–200 V for 90 minutes (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). The membranes were rinsed and then blocked using TBS based Odyssey® Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies specific for p65, IκBα, IKKβ, phospho-IKKβ (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), phospho-Stat1 (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX), Stat1 (ThermoFisher, Wilmington, DE), or actin (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) at recommended dilutions. Membranes were washed and subsequently incubated with the appropriate IRDye Subclass Specific secondary antibody (IRDye 680RD Goat anti-rabbit or IRDye 800CW Goat anti-mouse, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Membranes were imaged and analyzed using the Odyssey® CLx Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). Quantification was performed using ImageJ.

IKKβ Kinase Assay

A two-plate HTRF assay was used to examine the effects of AZM on IKKβ kinase activity. The assay detects endogenous levels of IKKβ only when phosphorylated at Ser 177 and Ser 181 (32, 33). Polarized macrophages were stimulated with LPS and cells were lysed according to manufacturer protocol (Cisbio, Codolet, France). Supernatants were removed and cells were incubated with the supplemented lysis buffer for 30 minutes at room tempreture with shaking. After homogenization, samples were incubated with the antibody mix (Phospho-IKKβ Cryptate/Phospho-IKKβ d2 antibodies) for 2 hours at room tempreture in 384-well small volume white plates. Fluorescence emission was then read at 665nm and 620nm using Synergy H1 plate reader. HTRF ratios are calculated by dividing the fluorescene signal at 665nm by the fluorescene signal at 620 nm and multiplied by a factor of 104. CV% is equal to the standard deviation divided by the mean ration and multiplied by 100.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Comparison between groups was made via one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test multiple comparisons, paired sample T-test with McNemar’s test, or via two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test where appropriate. Repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests were utilized for time course experiments.

Results

Azithromycin prevents p65 nuclear translocation while increasing IKKβ concentrations

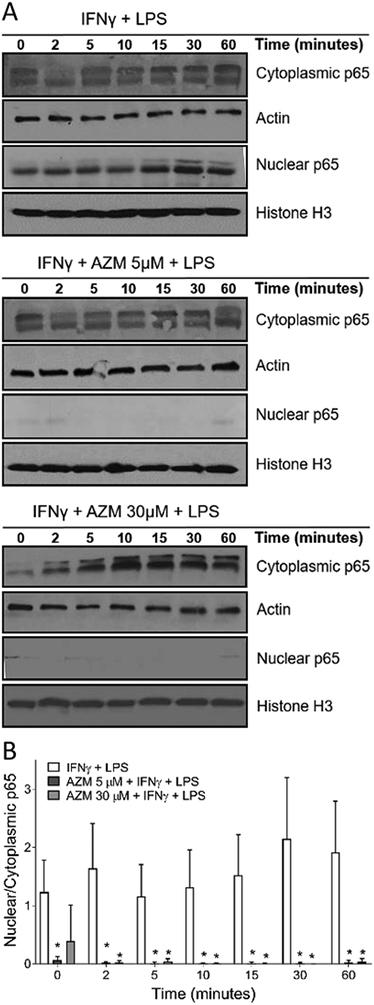

We first assessed the effects of azithromycin on the activation of transduction proteins involved in the NF-κB signaling cascade. Macrophages incubated overnight with IFNγ alone or with azithromycin were stimulated with LPS then fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions to assess the effects of azithromycin on the translocation of p65 subunits to the nucleus. (Fig. 1). Overnight incubation with IFNγ and stimulation with LPS (Fig. 1A) induced p65 nuclear translocation, with a peak in nuclear p65 fractions at 30 minutes post LPS stimulation. However, azithromycin treatment in the presence of IFNγ completely prevented p65 translocation to the nucleus at all timepoints. Treatment with azithromycin at all concentrations tested was associated with retention of p65 in the cytoplasm, shown for azithromycin concentrations of 5 μM and 30 μM. This was coupled with decreased p65 fractions in the nuclei of cells treated with azithromycin compared to cells treated with IFNγ only, with the ratios of p65 nuclear to cytosolic fractions shown over time in Fig. 1B.

Figure 1.

Azithromycin decreases NF-κB activation and prevents p65 nuclear translocation. J774 cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 cells per 1 ml of media in 24 well plates. Cells were allowed to attach for 8 hours and were then polarized overnight with IFNγ (50U/ml) alone or with azithromycin over a range of concentrations. Cells were then stimulated with LPS (10 nM) for durations ranging from 0 to 60 minutes. (A) Cells were harvested by scrapping and the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were separated. Western blots were performed to detect p65 in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. (B) Bar graph represents the ratio of nuclear to cytoplasmic fractions of p65 from (A). Nuclear fractions are normalized to histone H3 and cytoplasmic fractions are normalized to actin. Data are depicted as mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. AZM-treated groups were compared to the control group ((*) p-value < 0.05).

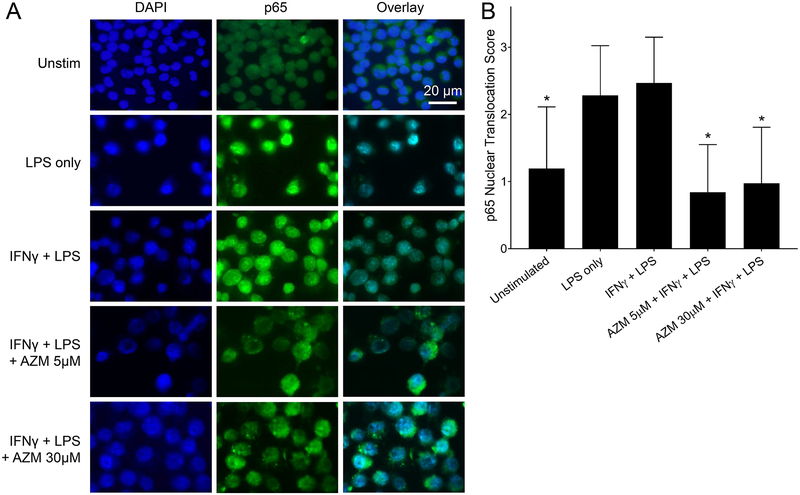

Additionally, immunostaining was used to visualize the localization of p65 subunits relative to the nucleus at 30 minutes post LPS stimulation (Fig. 2). NF-κB p65 subunits were stained with a FITC-conjugated antibody (green). The p65 signal was overlayed with the DAPI stained nuclei (blue) to determine the localization of the subunits in the polarized macrophages (Fig. 2A). Similar to the observations in Fig. 1, a strong nuclear signal was observed in IFNγ polarized macrophages while azithromycin treatment was associated with a strong cytoplasmic signal. The nuclear translocation scoring (Fig. 2B) shows a significant decrease in p65 nuclear translocation with azithromycin treatment at all the concentrations tested compared to IFNγ polarized macrophages. Similar results were also observed using primary BMDMs, with azithromycin causing blunted p65 nuclear translocation to a similar extent (Fig. S1 and S2).

Figure 2.

NF-κB p65 subunit accumulates in the cytoplasm around the nuclear membrane in azithromycin treated macrophages. J774 murine macrophages were plated at 2.5 × 105 cells on round glass coverslips. Cells were allowed to attach to the glass and then polarized overnight with IFNγ (50U/ml) alone or along with azithromycin. Cells were then stimulated with LPS (10 nM) for 30 minutes. (A) Immunofluorescence staining for the p65 subunit of NF-κB at 100X. Images show NF-κB p65 subunits stained in green (FITC) overlayed with DAPI nuclear staining. (B) Bar graphs represent the nuclear versus cytoplasmic fractions of p65 quantified using a scoring system as follows: p65 signal in cytoplasm only (score 0), evenly distributed between the nucleus and cytoplasm (score 1), mostly nuclear with faint cytoplasmic signal (score 2), or nuclear signal only (score 3). Data values depict mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance determined by two-way ANOVA, with AZM treated groups compared to the control (IFNγ plus LPS) condition ((*) p-value < 0.05).

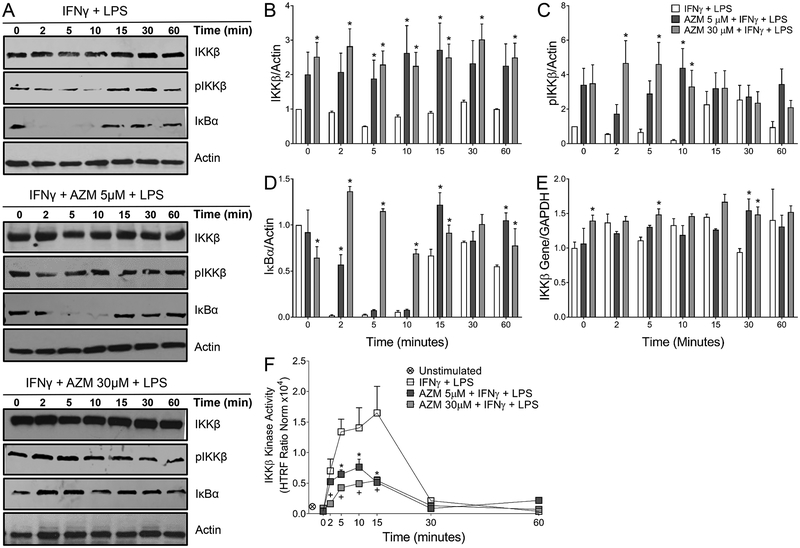

The impact of azithromycin treatment upon the expression of NF-κB associated proteins was then assessed. The amounts of IκBα, IKKβ, and phospho-IKKβ were measured by Wester blot over time after incubation overnight with azithromycin and IFNγ and stimulation with LPS as described in Methods (Fig. 3A). The amount of IKKβ present in cell lysates remained relatively constant across all timepoints for the control and azithromycin treatment conditions, but was increased at all timepoints by azithromycin even before the addition of LPS (Fig. 3B). This baseline increase was sustained throughtout the 60 minute assay period. Similarly, azithromycin polarized macrophages displayed increases in phospho-IKKβ levels compared to cells polarized with only IFNγ through 10 minutes after LPS addition (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Azithromycin prevents IκB-α degradation while accumulating IKKβ. J774 cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 cells per 1 ml of media in 24 well plates. Cells were allowed to attach for 8 hours and then were polarized overnight with IFNγ (50U/ml) alone or along with azithromycin at concentrations ranging from 5 to 100 μM. Cells were then stimulated with LPS (10 nM) and harvested at timepoints between 0 and 60 minutes. Proteins and RNA were then collected and probed for mediators in the NF-κB signaling cascade using Western blot, RT-PCR, and HTRF assay. (A) Western blots depict IκB-α, IKKβ, phospho-IKKβ and actin over time. (B, C, D) Relative fold change over time post LPS simulation of IKKβ, phospho-IKKβ, and IκB-α respectively. IKKβ, phospho-IKKβ, and IκB-α band intensities were normalized to actin and the control condition at time 0. Data represents mean ± SD (p-value < 0.05 (*)). (E) Relative fold change in IKKβ gene expression calculated from the ΔΔCt values, normalized to GAPDH, and compared to IFNγ treated macrophages at time 0. Data represents mean ± SD (p-value < 0.05 (*)). (F) Changes in IKKβ kinase activity over time post LPS stimulation. HTRF ratios were calculated from the flurorescense signals at 665nm and 620nm and are representative of the kinase activity of IKKβ. Values represent mean ± %CV (p-value < 0.05 (*) AZM 5 μM; (+) AZM 30 μM) and are normalized to total IKKβ and actin. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Additionally, azithromycin affected the degradation of IκBα in macrophages upon LPS stimulation. For cells incubated with IFNγ, LPS caused the expected decrease in IκBα within 2 minutes (Fig. 3). This is due to activation of this pathway, because when IκBα is phosphorylated it is rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded. However, azithromycin at concentrations of 5 μM delayed the degradation kinetics of IκBα, and at a concentration of 30 μM the drug blocked its degradation entirely, as graphically represented in Figure 3D. Within 10 minutes of NF-κB activation, resynthesis of IκBα was observed in macrophages polarized with IFNγ.

The increase in IKKβ is potentially a result of the inhibition of p65 translocation to the nucleus in azithromycin polarized macrophages. Termination of the NF-κB pathway involves resynthesis of IκBα induced by the activated NF-κB as well as downregulation of IKKβ synthesis, as IKKβ gene (Ikbkb) transcription is inhibited when p65 is in the nucleus as a feedback mechanism (11, 19, 34–37). To test this, we compared messenger RNA expression for Ikbkb via RT-PCR and found that azithromycin treatment caused a modest increase as compared to the control condition (Fig. 3E). Significant differences were observed with an increase in gene expression at some timepoints including time zero, however the increased gene expression of Ikbkb induced by azithromycin was not substantial, with only moderate increases of approximately 1.5 times control expression levels observed.

Lastly, because azithromycin blunts IκBα degradation in the presence of increased IKKβ protein expression, we sought to determine whether the drug affects IKKβ kinase activity. Activated phospho-IKKβ (Ser177/181) was detected using antibodies labelled with Eu3+-Cryptate (donor) and d2 (acceptor). Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) is triggered when the two dyes are in close proximity thus fluorescing at a specific wavelength of 665 nm. The flourescese signal is proportional to the phospho-IKKβ at Ser177/181, which is measured as a surrogate for kinase activity. Kinase activity increased as expected after LPS stimulation in the control cells over time. Azithromycin treatment was associated with significantly lower IKKβ kinase activity (when normalized to actin and IKKβ protein levels) between 5 and 15 minutes after stimulation compared to the IFNγ polarized macrophages (Fig. 3F). By 30 minutes post-LPS stimulation, kinase activity returned to baseline levels in all treatment groups. Similar results were demonstrated using primary mouse BMDMs polarized with azithromycin (Fig. S1, C).

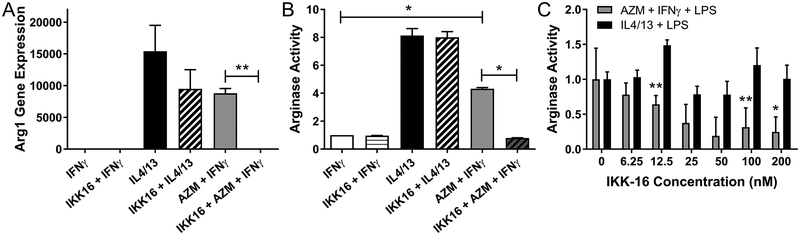

Inhibition of IKKβ activation prevents azithromycin from increasing production of the M2 macrophage effector protein arginase

Because azithromycin increased the amount of IKKβ present, we sought to determine whether azithromycin exerts its effect on macrophage polarization via this mechanism. A previous report by Fong et. al. shows that excessive IKKβ activation prevents the induction of pro-inflammatory characteristics of macrophages (38). We treated macrophages with cytokines and azithromycin to polarize them into either M1 or M2 cells, and in addition added IKK-16, an inhibitor of IKKβ (Fig. 4). This inhibitor displays a high affinity for IKKβ, with an IC50 of 40nM. At higher concentrations, it can also inhibit the activation of the entire IKK complex (39). Arginase-1 (Arg1) is an important effector of M2 macrophages and it is a marker of M2 macrophage polarization induced in response to Th2 cytokines (40). Azithromycin increased Arg1 gene expression in cells incubated with IFNγ and exposed to LPS (Fig. 4A). The addition of the IKKβ inhibitor significantly negated the effect of azithromycin on Arg1 gene expression. Interestingly, the decrease in Arg1 gene expression was not statistically significant when IKK-16 was added to wells treated with IL4 and IL13 (the M2 control condition) (p=0.115). These data suggest that azithromycin’s ability to induce expression of Arg1, an important M2 effector, is dependent on its effect on IKKβ.

FIGURE 4.

Azithromycin induced arginase gene expression and activity are reversed with IKKβ inhibition. J774 cells were stimulated overnight with IFNγ, IL4 and IL13, or with azithromycin (concentration 10 μM shown here) plus IFNγ in the presence or absence of the IKKβ inhibitor, IKK-16. Cells were then stimulated with LPS for 24 hours. (A) Arginase-1 gene expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. Bar graphs represent fold change in arginase-1 gene expression calculated from the ΔΔCt values normalized to GAPDH and compared to IFNγ treated macrophages. (B) Arginase activity as determined using an enzymatic assay in lysates from polarized macrophages. Data values represent fold change in arginase activity calculated from the standard curve under different polarization conditions compared to IFNγ treated macrophages. (C) Fold-change in arginase activity with increasing IKK-16 concentrations compared to no inhibitor treatment for cells treated with IFNγ plus AZM or with IL4/13. Data depicts mean ± SD and is representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA (p-value of < 0.05 (*); p-value of <0.0001 (**)).

We next assessed the effect of IKK-16 on arginase protein activity (Fig. 4B). In this series of experiments cells were treated with 100nM of IKK-16, a concentration chosen due to its maximal inhibition. Once again azithromycin increased the amount of arginase activity as previously published, but not to the extent of the M2 control condition of IL4 and IL13 treatment. The inhibitor had no effect on arginase activity in cells treated with IL4 and IL13 plus LPS, but for the cells incubated with azithromycin, treatment with IKK-16 decreased arginase activity to similar levels as cells that were not exposed to the drug. When cells were treated with increasing concentrations of IKK-16, the inhibition of azithromycin-induced arginase activity was consistent over a wide range of concentrations, with statistically significant decreases from 12.5 to 200nM (Fig. 4C). The inhibition of IKKβ had a little effect however on IL4 and IL13-dependent arginase production over the broad range of concentrations.

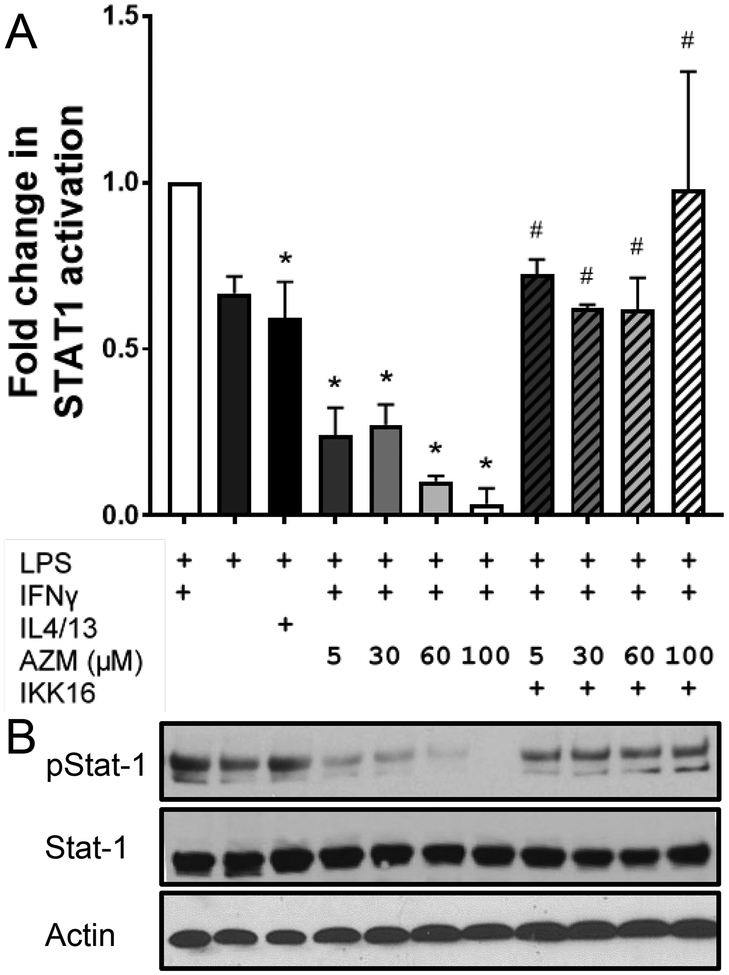

Inhibition of STAT-1 phosphorylation by azithromycin is dependent upon IKKβ

We then assessed the effect of azithromycin on the phosphorylation of STAT-1. Phosphorylated STAT-1 dimerizes and translocates to the nucleus of the cell where it initiates the transcription of several cytokines and inflammatory genes, most of which are associated with M1 macrophage activation (11, 12). J774 macrophages were polarized under conditions to drive them to either an M1 (IFNγ) or an M2 (IL4/13) phenotype. IFNγ-treated cells were also polarized in the presence of different azithromycin concentrations. After stimulation with LPS we assessed the concentrations of phospho-STAT-1 and STAT-1. As shown in Fig. 5, IFNγ activated STAT-1 leading to an increase in the phosphorylated form, whereas IL4 and IL13 blunted this increase in phosphorylation and resulted in lower levels of phospho-STAT-1 as expected. The LPS alone control had similar levels of phospho-STAT-1 as the media control. Azithromycin treatment also blunted IFNγ-dependent STAT-1 phosphorylation decreasing phospho-STAT-1 levels in a concentration-dependent manner. These results support our previous observation that azithromycin blunts NF-κB activation and subsequently shifts macrophage polarization away from the M1 phenotype. Inhibiting IKKβ via IKK-16 was associated with a reversal of azithromycin’s effect, with the addition of IKK-16 to the azithromycin-polarized macrophages restoring the phosphorylation of STAT-1. Additionlly, primary BMDMs polarized with azithromycin also show decreased STAT1 activation compared to IFNγ polarized BMDMs, an effect which is again reversed by IKK-16 treatment (Fig. S3).

FIGURE 5.

Azithromycin prevents STAT-1 activation via an IKKβ-dependent mechanism. J774 cells were plated at 2.5 × 105 cells per 1 ml of media in 24 well plates. Cells were then polarized with IL4 and IL13 (10 nM each), IFNγ (50U/ml) alone, or with IFNγ plus azithromycin (5, 30, 60, and 100 μM) with or without IKK-16 (100 nM). After overnight polarization cells were stimulated with LPS (10 nM) for 15 minutes and proteins were harvested by cell lysis. (A) Bar graph represents fold change in STAT-1 phosphorylation under different polarization conditions compared to IFNγ and LPS stimulated macrophages (normalized to actin and STAT-1 levels) depicted by Western blot in (B). Western blot represents treatment conditions denoted above each lane corresponding with (A). Data depicts mean ± SD and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test ((*) denotes significant difference compared to IFNγ + LPS; (#) denotes significant difference compared to the corresponding AZM concentration with no IKK16 treatment; p-value < 0.05).

Discussion

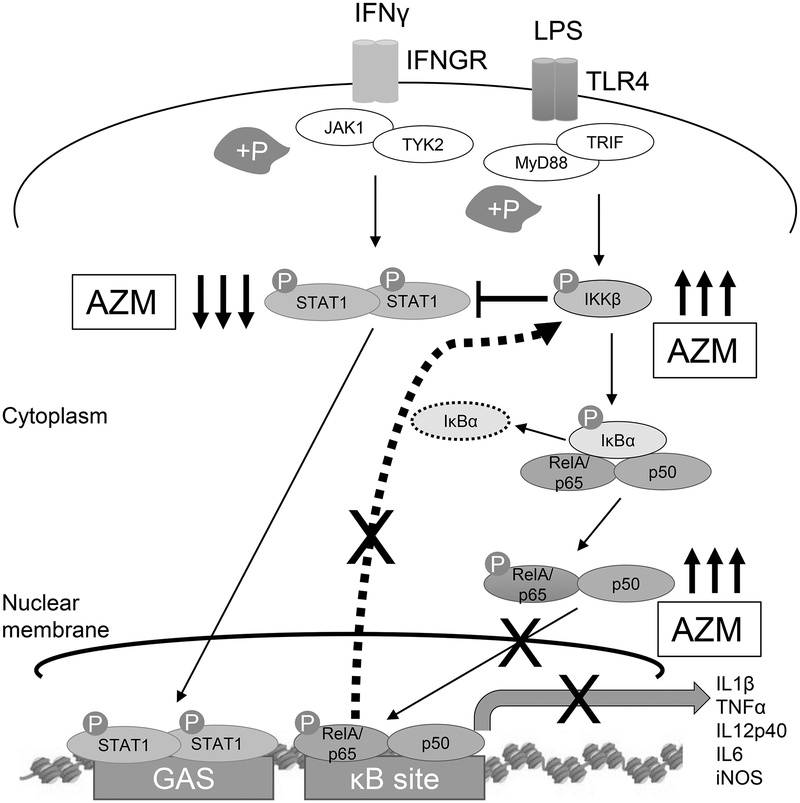

Macrophages constitute the first line of defense for pathogen infiltration into the lungs through their ability to initiate inflammation. This is accomplished in the case of Gram-negative pathogens primarily through the binding of TLR4 to bacterial LPS (41). NF-κB activation, through the binding of IFNγ and LPS, leads to the transcription of inflammatory genes including cytokines and chemokines. The NF-κB signaling cascade synergizes with STAT-1 activation to polarize macrophages to this classically activated phenotype (11, 12). Here we demonstrate that the immunomodulatory mechanism of azithromycin involves elements of both of these pathways, which results in the inhibition of the translocation of p65 to the nucleus. The production of IKKβ is also increased by the drug, which in turn blocks the phosphorylation of STAT-1, further increasing the expression of M2 effectors (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

The proposed interaction induced by azithromycin (AZM) is depicted. Azithromycin inhibits IFNγ-induced STAT-1 activation as well as inhibiting LPS mediated NF-κB activation. The nuclear translocation of p65 that results in pro-inflammatory gene transcription is inhibited by azithromycin. This is due, in part, to sustained IκBα levels at higher azithromycin concentrations, likely stemming from decreased kinase activity of IKKβ. Because p65 nuclear translocation is inhibited at time zero and at low azithromycin concentrations, additional mechanisms are likely at work. Increased total IKKβ is in part caused by a loss of negative feedback which otherwise shuts down the inflammatory signal by decreasing IKKβ production through decreased IKKβ gene expression. Accumulated IKKβ protein cross-inhibits the STAT-1 signaling pathway by decreasing STAT-1 phosphorylation thereby decreasing the associated pro-inflammatory gene transcription and increasing the expression of the M2-associated proteins including arginase-1.

Neutrophils migrate into infected tissues to prevent bacterial pathogen replication and spread. In chronic inflammatory lung conditions, responses to bacteria like P. auruginosa induce exaggerated or prolonged neutrophilia leading to pulmonary damage and fibrosis. Lung scaring is caused by excessive neutrophil elastase concentrations, an imbalance in the protease-antiprotease ratio, and a vicious cycle of excessive inflammation (42–46). While many groups have demonstrated that azithromycin reduces NF-κB activation (31, 47–50), our previous work showed that azithromycin also polarizes macrophages to an M2-like phenotype, both in vitro and in vivo during P. auruginosa infection (6, 7). Subsequently, we demonstrated in a mouse model of P. auruginosa infection that polarizing the macrophage response to one in which the M2 phenotype predominates early in the inflammatory process reduces neutrophil influx, decreases inflammation, and reduces fibrotic changes that correlate to improved morbidity and survival (7). Other effects included decreased production of iNOS and an increased production of the M2 effectors, mannose receptor and arginase-1. Our results show that, when the addition of azithromycin polarizes the macrophage response early in the infection, lung damage is mitigated (7). The efficacy of azithromycin in this setting is also reflected in clinical practice, as this agent is used as a chronic therapy for patients with cystic fibrosis. This is reflected in our methods to incubate cells with AZM overnight before exposing cells to LPS. Multiple clinical trials have demonstrated that quality of life is improved with chronic use of azithromycin, and extended treatment with azithromycin slows the decline of pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis who are colonized with P. aeruginosa (51–53). We have observed in our mouse model that the clearance of P. aeruginosa is not altered, and likewise no changes in the incidence of bacterial infection have been observed in these studies that place subjects on azithromycin long-term (51–53).

Additional published studies corroborate the results presented here. Previous reports demonstrate that the nuclear translocation of phospho-p65 is inhibited by azithromycin (49, 50). Additionally, Vrancic et al. showed no overall impact of azithromycin on the phosphorylation of p65—this is consistent with our findings when factoring in the increase in phospho-p65 in the cytoplasmic fraction that we observed (48). They also demonstrated that azithromycin inhibits the phosphorylation of STAT-1. We extend these studies here in our model to prove a direct relationship between increased IKKβ protein concentrations and this effect on STAT-1 through experimentally blocking IKKβ through competitive inhibition.

Evidence from the work by Fong and colleagues alludes to a link between the NF-κB and STAT-1 signaling pathways. This group demonstrated that the NF-κB signaling molecule IKKβ can inhibit STAT-1 signaling in macrophages in a model of Group B Streptococcus infection (38). While deletion of IKKβ in airway epithelial cells led to a decrease in inflammation, macrophage-specific deletion of IKKβ caused a resistance to Group B Streptococcus infection that was associated with increased expression of M1-associated inflammatory molecules including IL-12, iNOS, and MHCII (38). Additionally, in macrophages infected with Group B Streptococcus and in macrophages incubated with IFNγ, the absence of IKKβ led to an increase in phosphorylation of STAT-1 (38). These findings, along with our data, suggest that the increase in IKKβ expression in macrophages by azithromycin may be the mechanism through which polarization to the M2 phenotype occurs.

There are other examples of small molecules that inhibit the translocation of NF-κB including aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and 1,8-Cineol (54–57). The nuclear binding of p65 normally provides a feedback signal to shut down the production of IKKβ (19, 58–63). Therefore, it is likely that the inhibition of p65 translocation contributes to the increase in IKKβ production. Additionally, IKKβ degradation occurs through a mechanism of autophosphorylation. Because p65 concentrations are high in the cytoplasm, this autophosphorylation process is likely decreased, which turns the degradation pathway off (33, 58, 64–68). We have shown by PCR that message expression for Ikbkb is increased, therefore a reversal of the feedback loop is at least partly responsible. However, the difference is moderate and message expression is not increased until 30 minutes after LPS stimulation at lower azithromycin concentrations, whereas the IKKβ protein expression is increased earlier, even at time zero, suggesting other potential mechanisms at work.

Despite the evidence concerning macrophage polarization, the primary immunomodulatory mechanism of azithromycin remains to be discovered. Clearly NF-κB activation is highly dependent upon the degradation of IκB (58, 60, 63, 69). Our data shows that with higher azithromycin concentrations, degradation of IκBα is inhibited, leading to decreases in p65 nuclear translocation. The IκBα concentration is decreased upon stimulation with LPS for 30 minutes, and then rebounds to baseline concentrations (Fig. 3), with p65 translocation peaking at the corresponding 30-minute timepoint (Fig. 1)—all of which is blocked by azithromycin. It is likely that the decrease in IKKβ kinase activity (Fig. 3) is a critical aspect of the drug’s mechanism which is the likely cause of the effect on IκBα, although other aspects including proteosomal degredation could also be affected. Additionally, the fact that p65 translocation is inhibited at time zero and by lower (5 μM) azithromycin concentrations provides additional evidence that other mechanisms are likely at work. This will be a focal point for future investigations.

Nuclear translocation of p65 also depends upon a number of other factors. Alteration of the nuclear location sequence of p65 can occur through a number of mechanisms, including changes in the dimerization or improper folding, which are both required. The function of importins and other nuclear shuttling machinery (70–72), and permeability characteristics of the nuclear membrane can be disrupted (73–78). Additionally, acetylation of the activated subunit in the nucleus at multiple lysine residues is required for translocation and is governed by histone regulation and coactivators such as CREP-binding protein (79–82). We are continuing to evaluate the impact of azithromycin on these mechanisms.

Future studies will investigate whether the modulation of macrophage phenotype with azithromycin via inhibition of the NF-κB and STAT-1 signaling pathways is beneficial in patients with cystic fibrosis. Several groups have studied the impact of macrolides including azithromycin, clarithromycin, and erythromycin on ERK1/2 and p35 MAPK signaling cascades which result in decreased downstream NF-κB and AP-1 signaling. Azithromycin was shown in vivo and in vitro, both in human and murine cell culture models, to decrease NF-κB activation, decrease its nuclear translocation, and decrease NF-κB and Sp1 transcription factor binding to DNA (31, 48, 50, 83, 84). These effects were associated with a significant reduction in inflammatory cell infiltration into infected lungs, and a profound decrease in proinflammatory cytokine concentrations in the alveolar space. Groups studying the anti-inflammatory mechanisms of azithromycin show that decreases in NF-κB activation lead to suppressed induction of pro-inflammatory gene and protein expression in different murine and in vitro models of various inflammatory and infectious diseases (30, 31, 47–50, 84, 85). We expanded these studies here to address the specific effects on the upstream mediators of the NF-κB signaling cascade and their interaction with the other inflammatory signaling pathways.

In conclusion, the immunomodulation of macrophage function by azithromycin is a complex effect associated with the alteration of STAT1 signaling through the inhibition of NF-κB mediators, linked through the drug’s effect on IKKβ. Macrolides effect the polarization of macrophages in several models of inflammation. Studies have been extended to investigate the impact of azithromycin-polarized macrophages in spinal cord injury, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction (86, 87). An improved understanding of the mechanisms associated with these agents could lead to promising therapeutic target discovery in these and other devastating disease processes. And, defining interactions between signaling pathways will lead to a better understanding of cellular biology and provide the impetus for future drug discovery.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

1. Azithromycin’s immunomodulatory mechanism involves both NF-κB and STAT1 pathways

2. Azithromycin’s impact on STAT1 phosphorylation works in part through IKKβ

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Cynthia Mattingly.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases under Award Number R01AI095307 to D.J.F.

Abbreviations used in this article:

- AZM

azithromycin

- IKK

IκB kinase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IRF

interferon regulatory transcription factor

- HTRF

homogeneous time resolved fluorescence

References

- 1.Herbert DR, Holscher C, Mohrs M, Arendse B, Schwegmann A, Radwanska M, Leeto M, Kirsch R, Hall P, Mossmann H, Claussen B, Forster I, and Brombacher F. 2004. Alternative macrophage activation is essential for survival during schistosomiasis and downmodulates T helper 1 responses and immunopathology. Immunity 20: 623–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, and Donaldson DD. 1998. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science 282: 2258–2261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reece JJ, Siracusa MC, and Scott AL. 2006. Innate immune responses to lung-stage helminth infection induce alternatively activated alveolar macrophages. Infect. Immun 74: 4970–4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pesce JT, Ramalingam TR, Mentink-Kane MM, Wilson MS, El Kasmi KC, Smith AM, Thompson RW, Cheever AW, Murray PJ, and Wynn TA. 2009. Arginase-1-expressing macrophages suppress Th2 cytokine-driven inflammation and fibrosis. PLoS Pathog 5: doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morty RE, Konigshoff M, and Eickelberg O. 2009. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling across ages: from distorted lung development to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc 6: 607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy BS, Sundareshan V, Cory TJ, Hayes D Jr, Anstead MI, and Feola DJ. 2008. Azithromycin alters macrophage phenotype. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 61: 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feola DJ, Garvy BA, Cory TJ, Birket SE, Hoy H, Hayes D Jr., and Murphy BS. 2010. Azithromycin alters macrophage phenotype and pulmonary compartmentalization during lung infection with Pseudomonas. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 54: 2437–2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maarsingh H, Pera T, and Meurs H. 2008. Arginase and pulmonary diseases. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol 378: 171–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson RL, Burns JL, and Ramsey BW. 2003. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 168: 918–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lycza JB, Cannon CL, and Pier GB. 2002. Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 15: 194–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christian F, Smith EL, and Carmody RJ. 2016. The Regulation of NF-kappaB Subunits by Phosphorylation. Cells 5: doi: 10.3390/cells5010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gough DJ, Levy DE, Johnstone RW, and Clarke CJ. 2008. IFNgamma signaling-does it mean JAK-STAT? Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 19: 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovarik P, Stoiber D, Novy M, and Decker T. 1998. Stat1 combines signals derived from IFN-gamma and LPS receptors during macrophage activation. EMBO J 17: 3660–3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Locati M, Mantovani A, and Sica A. 2013. Macrophage activation and polarization as an adaptive component of innate immunity. Adv. Immunol 120: 163–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang N, Liang H, and Zen K. 2014. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage M1–M2 polarization balance. Front. Immunol 5: 614. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rath M, Müller I, Kropf P, Closs EI, and Munder M. 2014. Metabolism via arginase or nitric oxide synthase: two competing arginine pathways in macrophages. Front. Immunol 5: doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovarik P, Stoiber D, Novy M, and Decker T. 1998. Stat1 combines signals derived from IFN‐γ and LPS receptors during macrophage activation. EMBO J 17: 3660–3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun SC 2011. Non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Res 21: 71–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oeckinghaus A, and Ghosh S. 2009. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4: doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koehler DR, Downey GP, Sweezey NB, Tanswell AK, and Hu J. 2004. Lung inflammation as a therapeutic target in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol 31: 377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pahl HL 1999. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-κB transcription factors. Oncogene 18: 6853–6866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghosh S, and Karin M. 2002. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 109 Suppl: S81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang WC, Chen JJ, and Chen CC. 2003. c-Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of IKKbeta is involved in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression. J. Biol. Chem 278: 9944–9952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li JD, Feng W, Gallup M, Kim JH, Gum J, Kim Y, and Basbaum C. 1998. Activation of NF-κB via a Src-dependent Ras-MAPK-pp90rsk pathway is required for Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced mucin overproduction in epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 95: 5718–5723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daley JM, Leadley TA, and Drouillard KG. 2009. Evidence for bioamplification of nine polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners in yellow perch (Perca flavascens) eggs during incubation. Chemosphere 75: 1500–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra BB, Gundra UM, and Teale JM. 2011. STAT6(−)/(−) mice exhibit decreased cells with alternatively activated macrophage phenotypes and enhanced disease severity in murine neurocysticercosis. J. Neuroimmunol 232: 26–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelms K, Keegan AD, Zamorano J, Ryan JJ, and Paul WE. 1999. The IL-4 receptor: signaling mechanisms and biologic functions. Annu. Rev. Immunol 17: 701–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutschman R, Lang R, Hesse M, Ihle JN, Wynn TA, and Murray PJ. 2001. Cutting edge: Stat6-Dependent Substrate Depletion Regulates Nitric Oxide Production. J. Immunol 166: 2173–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weng M, Huntley D, Huang I-F, Foye-Jackson O, Wang L, Sarkissian A, Zhou Q, Walker WA, Cherayil BJ, and Shi HN. 2007. Alternatively activated macrophages in intestinal helminth infection: effects on concurrent bacterial colitis. J. Immunol 179: 4721–4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheung PS, Si EC, and Hosseini K. 2010. Anti-inflammatory activity of azithromycin as measured by its NF-kappaB, inhibitory activity. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm 18: 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cigana C, Assael BM, and Melotti P. 2007. Azithromycin selectively reduces tumor necrosis factor alpha levels in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 51: 975–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanaka H, Fujita N, and Tsuruo T. 2005. 3-Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1-mediated IkappaB kinase beta (IkkB) phosphorylation activates NF-kappaB signaling. J. Biol. Chem 280: 40965–40973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delhase M, Hayakawa M, Chen Y, and Karin M. 1999. Positive and negative regulation of IkappaB kinase activity through IKKbeta subunit phosphorylation. Science 284: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shih VF, Tsui R, Caldwell A, and Hoffmann A. 2011. A single NFkappaB system for both canonical and non-canonical signaling. Cell Res 21: 86–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreno R, Sobotzik JM, Schultz C, and Schmitz ML. 2010. Specification of the NF-κB transcriptional response by p65 phosphorylation and TNF-induced nuclear translocation of IKKε. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 6029–6044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hacker H, and Karin M. 2006. Regulation and function of IKK and IKK-related kinases. Sci. STKE 2006: doi: 10.1126/stke.3572006re13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoesel B and Schmid JA. 2013. The complexity of NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer 12: doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fong CH, Bebien M, Didierlaurent A, Nebauer R, Hussell T, Broide D, Karin M, and Lawrence T. 2008. An antiinflammatory role for IKKbeta through the inhibition of “classical” macrophage activation. J. Exp. Med 205: 1269–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waelchli R, Bollbuck B, Bruns C, Buhl T, Eder J, Feifel R, Hersperger R, Janser P, Revesz L, and Zerwes H-G. 2006. Design and preparation of 2-benzamido-pyrimidines as inhibitors of IKK. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 16: 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briken V and Mosser DM. 2011. Editorial: switching on arginase in M2 macrophages. J. Leukoc. Biol 90: 839–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mogensen TH 2009. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 22: 240–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elizur A, Cannon CL, and Ferkol TW. 2008. Airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Chest 133: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rao S, and Grigg J. 2006. New insights into pulmonary inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Arch. Dis. Child 91: 786–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nichols D, Chmiel J, and Berger M. 2008. Chronic inflammation in the cystic fibrosis lung: alterations in inter- and intracellular signaling. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol 34: 146–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyer KC and Zimmerman J. 1993. Neutrophil mediators, Pseudomonas, and pulmonary dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. J. Lab. Clin. Med 121: 654–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abboud RT, and Vimalanathan S. 2008. Pathogenesis of COPD. Part I. The role of protease-antiprotease imbalance in emphysema. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis 12: 361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stellari FF, Sala A, Donofrio G, Ruscitti F, Caruso P, Topini TM, Francis KP, Li X, Carnini C, and Civelli M. 2014. Azithromycin inhibits nuclear factor‐κB activation during lung inflammation: an in vivo imaging study. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect 2: doi: 10.1002/prp2.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vrancic M, Banjanac M, Nujic K, Bosnar M, Murati T, Munic V, Stupin Polancec D, Belamaric D, Parnham MJ, and Erakovic Haber V. 2012. Azithromycin distinctively modulates classical activation of human monocytes in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol 165: 1348–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li DQ, Zhou N, Zhang L, Ma P, and Pflugfelder SC. 2010. Suppressive effects of azithromycin on zymosan-induced production of proinflammatory mediators by human corneal epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 51: 5623–5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanoh S, and Rubin BK. 2010. Mechanisms of action and clinical application of macrolides as immunomodulatory medications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 23: 590–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Equi A, Balfour-Lynn IA, Bush A, and Rosenthal M. 2002. Long term azithromycin in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Lancet 360: 978–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saiman L, Marshall BC, Mayer-Hamblett N, and Burns JL. 2003. Azithromycin in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290: 1749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolter J, Seeney S, Bell S, Bowler S, Masel P, and McCormack J. 2002. Effect of long term treatment with azithromycin on disease parameters in cystic fibrosis: a randomised trial. Thorax 57: 212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kopp E, and Ghosh S. 1994. Inhibition of NF-kappa B by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science 265: 956–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamamoto Y, Yin MJ, Lin KM, and Gaynor RB. 1999. Sulindac inhibits activation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J. Biol. Chem 274: 27307–27314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greiner JF, Muller J, Zeuner MT, Hauser S, Seidel T, Klenke C, Grunwald LM, Schomann T, Widera D, Sudhoff H, Kaltschmidt B, and Kaltschmidt C. 2013. 1,8-Cineol inhibits nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB p65 and NF-kappaB-dependent transcriptional activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833: 2866–2878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong BC, Jiang X, Fan XM, Lin MC, Jiang SH, Lam SK, and Kung HF. 2003. Suppression of RelA/p65 nuclear translocation independent of IkappaB-alpha degradation by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor in gastric cancer. Oncogene 22: 1189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karin M 1999. How NF-kappaB is activated: the role of the IkappaB kinase (IKK) complex. Oncogene 18: 6867–6874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perkins N and Gilmore T. 2006. Good cop, bad cop: the different faces of NF-κB. Cell Death Differ 13: 759–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scheidereit C 2006. IkappaB kinase complexes: gateways to NF-kappaB activation and transcription. Oncogene 25: 6685–6705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barisic S, Strozyk E, Peters N, Walczak H, and Kulms D. 2008. Identification of PP2A as a crucial regulator of the NF-kappaB feedback loop: its inhibition by UVB turns NF-kappaB into a pro-apoptotic factor. Cell Death Differ 15: 1681–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh S and Aggarwal BB. 1995. Activation of transcription factor NF-kappa B is suppressed by curcumin (diferuloylmethane). J. Biol. Chem 270: 24995–25000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gupta SC, Prasad S, Reuter S, Kannappan R, Yadav VR, Ravindran J, Hema PS, Chaturvedi MM, Nair M, and Aggarwal BB. 2010. Modification of cysteine 179 of IkappaBalpha kinase by nimbolide leads to down-regulation of NF-kappaB-regulated cell survival and proliferative proteins and sensitization of tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents. J. Biol. Chem 285: 35406–35417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gupta SC, Sundaram C, Reuter S, and Aggarwal BB. 2010. Inhibiting NF-kappaB activation by small molecules as a therapeutic strategy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1799: 775–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schomer-Miller B, Higashimoto T, Lee Y-K, and Zandi E. 2006. Regulation of IκB kinase (IKK) complex by IKKγ-dependent phosphorylation of the T-loop and C terminus of IKKβ. J. Biol. Chem 281: 15268–15276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koul D, Yao Y, Abbruzzese JL, Yung WA, and Reddy SA. 2001. Tumor suppressor MMAC/PTEN inhibits cytokine-induced NFκB activation without interfering with the IκB degradation pathway. J. Biol. Chem 276: 11402–11408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Israel A 2010. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2: doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeong JY, Woo JH, Kim YS, Choi S, Lee SO, Kil SR, Kim CW, Lee BL, Kim WH, Nam BH, and Chang MS. 2010. Nuclear factor-kappa B inhibition reduces markedly cell proliferation in Epstein-Barr virus-infected stomach cancer, but affects variably in Epstein-Barr virus-negative stomach cancer. Cancer Invest 28: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meyer S, Kohler NG, and Joly A. 1997. Cyclosporine A is an uncompetitive inhibitor of proteasome activity and prevents NF-kappaB activation. FEBS Lett 413: 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Theiss AL, Jenkins AK, Okoro NI, Klapproth J-MA, Merlin D, and Sitaraman SV. 2009. Prohibitin inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha–induced nuclear factor-kappa b nuclear translocation via the novel mechanism of decreasing importin α3 expression. Mol. Biol. Cell 20: 4412–4423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu D, Lillico SG, Barnett MW, Whitelaw CB, Archibald AL, and Ait-Ali T. 2012. USP18 restricts PRRSV growth through alteration of nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB p65 and p50 in MARC-145 cells. Virus Res 169: 264–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guzman JR, Koo JS, Goldsmith JR, Muhlbauer M, Narula A, and Jobin C. 2013. Oxymatrine prevents NF-kappaB nuclear translocation and ameliorates acute intestinal inflammation. Sci Rep 3: doi:1038/srep01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin YZ, Yao S, Veach RA, Torgerson TR, and Hawiger J. 1995. Inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor NF-κB by a synthetic peptide containing a cell membrane-permeable motif and nuclear localization sequence. J. Biol. Chem 270: 14255–14258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Torgerson TR, Colosia AD, Donahue JP, Lin Y-Z, and Hawiger J. 1998. Regulation of NF-κB, AP-1, NFAT, and STAT1 nuclear import in T lymphocytes by noninvasive delivery of peptide carrying the nuclear localization sequence of NF-κB p50. J. Immunol 161: 6084–6092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Letoha T, Somlai C, Takács T, Szabolcs A, Jármay K, Rakonczay Z Jr, Hegyi P, Varga I, Kaszaki J, and Krizbai I. 2005. A nuclear import inhibitory peptide ameliorates the severity of cholecystokinin-induced acute pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol 11: 990–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abate A, Oberle S, and Schroder H. 1998. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in mouse macrophages is inhibited by chloromethylketones and a direct inhibitor of NF-kappa B translocation. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 56: 277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kolenko V, Bloom T, Rayman P, Bukowski R, Hsi E, and Finke J. 1999. Inhibition of NF-kappa B activity in human T lymphocytes induces caspase-dependent apoptosis without detectable activation of caspase-1 and −3. J. Immunol 163: 590–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mohan RR, Mohan RR, Kim WJ, and Wilson SE. 2000. Modulation of TNF-α–induced apoptosis in corneal fibroblasts by transcription factor NF-κB. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 41: 1327–1336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kiernan R, Bres V, Ng RW, Coudart MP, El Messaoudi S, Sardet C, Jin DY, Emiliani S, and Benkirane M. 2003. Post-activation turn-off of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription is regulated by acetylation of p65. J. Biol. Chem 278: 2758–2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen L, Fischle W, Verdin E, and Greene WC. 2001. Duration of nuclear NF-kappaB action regulated by reversible acetylation. Science 293: 1653–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen LF and Greene WC. 2004. Shaping the nuclear action of NF-kappaB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 5: 392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Corraliza IM, Campo ML, Soler G, and Modolell M. 1994. Determination of arginase activity in macrophages: a micromethod. J. Immunol. Methods 174: 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li DQ, Zhou N, Zhang L, Ma P, and Pflugfelder SC. 2010. Suppressive effects of azithromycin on zymosan-induced production of proinflammatory mediators by human corneal epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 51: 5623–5629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Matsumura Y, Mitani A, Suga T, Kamiya Y, Kikuchi T, Tanaka S, Aino M, and Noguchi T. 2011. Azithromycin may inhibit interleukin-8 through suppression of Rac1 and a nuclear factor-kappa B pathway in KB cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. J. Periodontol 82: 1623–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Iwamoto S, Kumamoto T, Azuma E, Hirayama M, Ito M, Amano K, Ido M, and Komada Y. 2011. The effect of azithromycin on the maturation and function of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol 166: 385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang B, Bailey WM, Kopper TJ, Orr MB, Feola DJ, and Gensel JC. 2015. Azithromycin drives alternative macrophage activation and improves recovery and tissue sparing in contusion spinal cord injury. J. Neuroinflammation 12: doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0440-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Al-Darraji A, Haydar D, Chelvarajan L, Tripathi H, Levitan B, Gao E, Venditto VJ, Gensel JC, Feola DJ, and Abdel-Latif A. 2018. Azithromycin therapy reduces cardiac inflammation and mitigates adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction: Potential therapeutic targets in ischemic heart disease. PLoS One 13: doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.