Abstract

Background and purpose:

AV-1451 (18F-AV-1451, flortaucipir) positron emission tomography (PET) was performed in C9orf72 expansion carriers to assess tau accumulation and disease manifestation.

Methods:

Nine clinically characterized C9orf72 expansion carriers and 18 age- and gender- matched cognitively normal individuals were psychometrically evaluated and underwent tau PET imaging. Regional AV-1451 standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) from multiple brain regions was analyzed. Spearman correlation was performed to relate AV-1451 SUVR to clinical, psychometric, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) measures.

Results:

C9orf72 expansion carriers had increased AV-1451 binding in entorhinal cortex compared to controls. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART) was observed post-mortem in one patient. AV-1451 uptake did not correlate with clinical severity, disease duration, psychometric performance, or CSF markers.

Conclusion:

C9orf72 expansion carriers exhibited increased AV-1451 uptake in entorhinal cortex when compared to cognitively normal controls, suggesting a propensity for PART. However, AV-1451 accumulation was not associated with psychometric performance in our cohort.

Keywords: C9orf72, Tau, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), positron emission tomography (PET), AV-1451

INTRODUCTION

The C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion is the most common genetic cause of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and fronto-temporal dementia (FTD). Nearly 50% of patients with C9orf72-related ALS develop cognitive impairment [1].

Cognitively impaired C9orf72 expansion carriers have been described with accumulation of intracellular tau fibrils [2, 3] and a pathologic burden of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) consistent with AD [3]. Other studies found minimal tau pathology in C9orf72-positive patients across the ALS/FTD spectrum [2].

PET tracers that bind to aggregated tau, such as AV-1451, provide a novel non-invasive approach for investigating the spatial accrual of tau [4] and have shown promise as biomarkers for disease progression in AD [5] and other tauopathies [6]. Here, we study the AV-1451 uptake in C9orf72 expansion carriers and examine relationships between AV-1451 binding and clinical features.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The study was approved by the Washington University in Saint Louis (WU) Institutional Review Board and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02414230). Participants (n= 9) were recruited from the WU neuromuscular clinic and provided written informed consent. All had an expanded C9orf72 allele by repeat-primed PCR through a CLIA-approved laboratory. None were diagnosed with FTD. Clinical history, physical exam, and a revised ALS functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R) assessment were collected. ALS cognitive behavioral score (ALS-CBS) was obtained from the medical record.

Eighteen cognitively normal participants (mean age: 63.9 ± 5.4 years, % male: 50%) were recruited from the WU Knight Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center to match our experimental cohort 2:1. Controls had a clinical dementia rating (CDR) score of zero and were amyloid-negative by imaging with 18F-AV-45.

Neuropsychological tests administered included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), trailmaking A (TMA), trailmaking B (TMB), letter-number sequencing (LNS), category fluency (animals), and the logical memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale III. One C9orf72 expansion carrier was unable to perform neuropsychological testing due to advanced disease. Four additional participants did not complete the logical memory subtest due to speech limitations.

CSF AD biomarker analysis

CSF Aβ42, total tau, and phospho-tau were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (INNOTEST®, Fujirebio-Europe; Ghent, Belgium) [7].

Brain Imaging

Structural MRI scans were acquired using a Biograph mMR PET-MRI scanner. AV-1451 PET scans ([18F] AV-1451,T807, flortaucipir) were acquired on a Siemens Biograph 40 PET-CT scanner for controls, or a Biograph mMR PET-MRI scanner for C9orf72 expansion carriers. Attenuation correction, tracer analysis, volumetric segmentation, and partial volume correction were preformed as previously described [8]. Scanner specific spatial filters were applied to achieve a common resolution (8 mm3) across PET scanners [9, 10]. Regional SUVRs were obtained using the cerebellar gray matter as a reference region during the 80 – 100 minute post-injection time. Additional comparisons to the brainstem and cortical regions were performed.

Neuropathologic analysis

Brain and spinal cord sections were analyzed by the Anatomic and Molecular Pathology Core Lab at WU.

Statistical analyses

AV-1451 SUVRs were compared by independent 2-tailed t-tests using a Bonferroni corrected p-value of 0.0042 (adjusted p-value= 0.05/ 12) to correct for multiple comparisons. Spearman correlation was used to relate AV-1451 uptake to clinical/paraclinical measures.

RESULTS

Clinical and Neuropsychological Characteristics

C9orf72 expansion carriers varied in site of onset, disease duration, and ALSFRS-R scores. Two participants, #2 and #7, did not display motor impairment (Table 1). C9orf72 expansion carriers performed worse on a global measure of neuropsychological performance (MMSE) and required longer times to complete TMA (control: 27.39 ± 8.49; C9orf72: 45.96 ± 12.56, p= 0.0003) and TMB (control: 64.06 ± 29.35; C9orf72: 105.5 ± 43.86, p= 0.011) tasks. TMA/TMB performance was not related to motor impairment from the ALSFRS-R handwriting subscore (TMA: Spearman r= −0.232, p= 0.529; TMB: Spearman r= −0.020, p= 0.781). Thus, C9orf72 expansion carriers had cognitive deficits in attentional and executive domains.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of C9orf72 expansion carriers. N/A- not available. Educational level denoted Bachelor’s degree (B), Master’s degree (M.S.), Doctorate (Ph.D.), High School (HS), or General Educational Development Test (GED). ALSFRS-R: revised amyotrophic lateral sclerosis functional rating scale. MMSE: mini-mental state examination. ALS-CBS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis cognitive behavioral score. TMA: Trailmaking A, TMB: Trailmaking B, LNS: Letter-Number-Sequence, sec: seconds. CSF biomarkers include Aβ, total-tau (t-tau), and phosphorylated tau (p-tau).

| Participant | Age | Gender | Site of Onset |

Disease Duration (years) |

ALSFRS-R (/48) |

MMSE (/30) |

ALS-CBS (/21) |

Ed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | Female | Spinal | 1.57 | 13 | N/A | N/A | B |

| 2 | 60 | Male | N/A | N/A | N/A | 30 | N/A | M.S. |

| 3 | 60 | Male | Bulbar | 1.21 | 37 | 30 | 17 | B |

| 4 | 65 | Female | Bulbar | 3.67 | 22 | 27 | 10 | N/A |

| 5 | 64 | Male | Spinal | 4.19 | 21 | 23 | 16 | M.S. |

| 6 | 69 | Male | Spinal | 2.67 | 25 | 24 | 8 | Ph.D. |

| 7 | 57 | Female | N/A | N/A | N/A | 25 | N/A | GED |

| 8 | 68 | Female | Bulbar | 2.25 | 39 | 30 | 20 | HS |

| 9 | 60 | Male | Spinal | 1.94 | 36 | 30 | N/A | HS |

| Avg | 63.0 ± 4.0 | 56% Male | N/A | 2.50 ± 1.09 | 28 ± 9.8 | 27.4 ± 3.0 | 14.2 ± 5.0 | |

| Control cohort demographics (n= 18) | ||||||||

| 63.5 ± 5.3 | 50% Male | N/A | N/A | N/A | 29.9 ± 0.4 | N/A | N/A | |

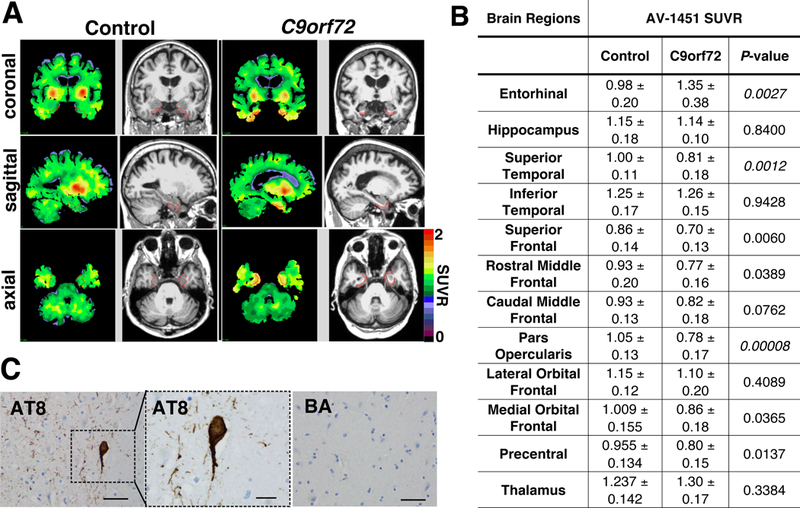

We examined AV-1451 SUVRs in regions commonly affected by C9orf72-related disease based on prior morphometric or pathologic studies [2, 3, 11]. The entorhinal cortex displayed elevated AV-1451 SUVR in C9orf72 expansion carriers (C9orf72: 1.347 ± 0.376, control: 0.982 ± 0.199, p= 0.0027) (Fig. 1A-B). No other targeted ROI displayed increased AV-1451 uptake (Fig. 1B). Since cerebellar pathology has been described in C9orf72-related disease [11], comparisons using AV-1451 SUVR normalized to brainstem and mean cortical regions were also performed and revealed increases in entorhinal tau deposition (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Tau PET uptake in C9orf72 expansion carriers and controls. A) Representative coronal, sagittal, and axial images showing regional distribution of cerebellar gray-normalized AV-1451 SUVR values and paired T2-weighted MRI images in C9orf72 expansion (right) and control participants (left). Entorhinal cortex is outlined in red. B) AV-1451 SUVR values in twelve brain regions. Statistics by student’s t-test using a Bonferroni significance level of 0.0042. C) Post-mortem analysis of hippocampus from a C9orf72 participant with tau PET SUVR of 1.26. Sections stained with AT8 antibody show tau reactivity (scale bar: 50 μm) in the entorhinal cortex. Inset shows tau pathology at higher magnification (scale bar: 20 μm). Entorhinal cortical sections stained for β-amyloid (BA) did not display reactivity (scale bar: 50 μm).

Neither ALSFRS-R (r= 0.357, p= 0.444) nor disease duration (r= 0.571, p= 0.200) correlated with entorhinal AV-1451 uptake suggesting that AV-1451 uptake is not associated with physical decline.

TMA/TMB performance has been associated with activation of frontal regions [12]. We examined relationships between TMA and TMB performance with AV-1451 SUVR in entorhinal (TMA: r= −0.071, p= 0.906; TMB: r= 0.571, p= 0.2), caudal middle frontal (TMA: r= −0.5, p= 0.267; TMB: r= −0.179, p= 0.713), and rostral middle frontal (TMA: r= −0.536, p= 0.236; TMB: r= 0.036, p= 0.964) regions. AV-1451 accumulation in frontal cortex was not associated with TMA or TMB performance.

CSF Aβ42 levels (CSF Aβ42: 973 ± 443 pg/mL) were within ranges reported for cognitively normal and amyloid negative individuals [7]. CSF biomarker levels did not correlate with entorhinal AV-1451 uptake in C9orf72 patients (Aβ: r= 0.543, p= 0.297; t-tau: 0.257, p= 0.658; p-tau: r= 0.257, p= 0.658).

Post-mortem analysis was performed on tissue from participant #3 (entorhinal SUVR 1.26). Staining for phospho-tau showed neurofibrillary tangles primarily within the entorhinal cortex. Entorhinal cortical sections did not exhibit β-amyloid deposition (Fig. 1C), consistent with PART.

DISCUSSION

Tau PET imaging in C9orf72 expansion carriers with motor and cognitive deficits revealed that a subset of had increased tau burden in the entorhinal cortex compared to controls. Prior pathological studies of tauopathy in C9orf72-related FTD and ALS/FTD [2, 3] identified a burden of neurofibrillary tangles that ranged from mild (in most cases) to moderate/high likelihood of AD by Braak staging. PART was seen in ~50% of C9orf72 expansion carriers. Post-mortem analysis of a C9orf72 and entorhinal tau PET-positive participant revealed entorhinal tau pathology in the absence of β-amyloid deposition, most consistent with PART. However, tau deposition was not associated with clinical features or psychometric performance \.

AV-1451 has been shown to bind neurofibrillary tangles and paired helical filament tau in situ [4]. However, its propensity to bind tau in alternatively modified or aggregated states is not well characterized. We cannot exclude the presence of alternative tau species with poor tracer affinity in C9orf72-related disease.

Study limitations include lack of testing for episodic memory or behavioral changes, relatively small sample size, and relatively mild cognitive burden in this cohort. A larger longitudinal study C9orf72 expansion carriers spanning from pure FTD to pure ALS would help address the predictive power of AV-1451 as a biomarker for cognitive impairment in these patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the WU Knight Alzheimer’s Research Imaging Program and the Knight ADRC clinical core for participant assessments. We thank Ms. Marina Platik for optimizing immunohistochemistry protocols. We thank our research participants and their families.

Funding for the study was received from a Washington University McDonnell Center grant; National Institutes of Health T32 Training grant NS007205 (Dr. Ly); American Academy of Neurology/ ALS Association Clinical Research Training fellowship (Dr. Ly); National Institute of Health grant K08NS107621; National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke grant P30 NS048056; the Hope Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders (Dr. Benzinger); the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation Willman Scholar Fund (Dr. Gordon); the American Society for Neuroradiology (Dr. Gordon); National Institute of Health grant K01AG053474 (Dr. Gordon); National Institute of Health grants P01AG03991, P50AG005681, P01AG026276, UL1TR000448, P30NS098577. Dr. Ances is funded by grants R01NR012907, R01NR012657, R01NR014449, 1R01AG057680, 1R01AG052550 from the National Institutes of Health and from the Paula and Rodger O Riney Fund. Dr. Miller is funded by grants R01NS078398, R01NS097816, R21NS099766, and U01MH10913301 from the National Institutes of Health. Support from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly) included provision of the precursor to AV-1451 and radiochemistry support.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

REFERENCES

- 1.Chio A, Borghero G, Restagno G, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis carrying the pathogenic GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat expansion of C9ORF72. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2012;135(Pt 3):784–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behrouzi R, Liu X, Wu D, et al. Pathological tau deposition in Motor Neurone Disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration associated with TDP-43 proteinopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bieniek KF, Murray ME, Rutherford NJ, et al. Tau pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with C9ORF72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion. Acta neuropathologica. 2013;125(2):289–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien DT, Bahri S, Szardenings AK, et al. Early clinical PET imaging results with the novel PHF-tau radioligand [F-18]-T807. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2013;34(2):457–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brier MR, Gordon B, Friedrichsen K, et al. Tau and Abeta imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(338):338ra–66.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi Y, Ha S, Lee YS, et al. Development of tau PET Imaging Ligands and their Utility in Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2018;52(1):24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vlassenko AG, McCue L, Jasielec MS, et al. Imaging and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in early preclinical alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2016;80(3):379–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon BA, Friedrichsen K, Brier M, et al. The relationship between cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer pathology and positron emission tomography tau imaging. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2016;139(Pt 8):2249–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi A, Koeppe RA, Fessler JA. Reducing between scanner differences in multi-center PET studies. NeuroImage. 2009;46(1):154–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon BA, Blazey TM, Su Y, et al. Spatial patterns of neuroimaging biomarker change in individuals from families with autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study. The Lancet Neurology. 2018;17(3):241–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Boeve BF, et al. Neuroimaging signatures of frontotemporal dementia genetics: C9ORF72, tau, progranulin and sporadics. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2012;135(Pt 3):794–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miskin N, Thesen T, Barr WB, et al. Prefrontal lobe structural integrity and trail making test, part B: converging findings from surface-based cortical thickness and voxel-based lesion symptom analyses. Brain imaging and behavior. 2016;10(3):675–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]