Abstract

In the present study the production of α-glycosidase inhibitors was used as a strategy to screen endophytic fungi with insecticidal and antifungal potential. Endophytic fungi were isolated from Calotropis gigantea L. (Gentianales: Apocynaceae) and evaluated for their α-glycosidase inhibitory activity. Maximum inhibitory activity was observed in an isolate AKL-3, identified to be Alternaria destruens E.G.Simmons on the basis of morphological and molecular analysis. Production of inhibitory metabolites was carried out on malt extract and partially purified using column chromatography. Insecticidal potential was examined on Spodoptera litura Fab. (Lepidoptera: Noctudiae). Partially purified α-glycosidase inhibitors induced high mortality, delayed the development period as well as affected the adult emergence and induced adult deformities. Nutritional analysis revealed the toxic and antifeedant effect of AKL-3 inhibitors on various food utilization parameters of S. litura. They also inhibited the in vivo digestive enzymes activity in S. litura. Partially purified α-glycosidase inhibitors were also studied for their antifungal potential. Inhibitors demonstrated antifungal activity against the tested phytopathogens inducing severe morphological changes in mycelium and spores. This is the first report on production of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens with insecticidal and antifungal activity. The study also highlights the importance of endophytes in providing protection against insect pests and pathogens to the host.

Subject terms: Fungal host response, Environmental microbiology

Introduction

Insect pests and fungal pathogens have become a source of concern as great losses to economically important crops are caused by them worldwide1–4. To alleviate their effect, excessive dependence on chemical pesticides has resulted in many environmental issues such as contamination of food and water sources, poisoning of non-target beneficial insects and resistance development in insect pests5,6. Researchers have focused on alternative methods to control pests with special emphasis on bio-control. Among bio-control agents, endophytes would be an ideal choice as these are integrated into the host plant. They are the microorganisms which spend the whole or part of their life cycle colonizing inter- or intra-cellularly, in the healthy living tissues of the host, without causing any symptoms7. These microbes confer benefits to the host plants such as greater access to the nutrients8–10, protection from insect pests, parasitic fungi, etc. and from abiotic stresses like desiccation11,12. The protective role of endophytes against insect pests and fungal pathogens has been well documented in literature13,14. Plants artificially inoculated with endophytic fungi were also found to demonstrate resistance against insect pests15,16. These microorganisms synthesize a number of bioactive compounds mainly alkaloids, phenols, terpenoids, sterols etc.17 which play a significant role in protecting their host plants from herbivores18–20. One of the mechanisms employed by these microbes for providing protection could be through inhibition of vital enzymes of pests and pathogens.

α-Amylase (3.2.1.1) and α-glucosidase (3.2.1.20) are glycoside hydrolase enzymes responsible for digestion of carbohydrates. These enzymes hydrolyze carbohydrates by acting on 1,4-α linkages, releasing D-glucose from the non-reducing end of the sugar21. In insects, these enzymes are found in the salivary secretions, hemolymph and alimentary canal22. The inhibition of these enzymes would slow the process of digestion; leading to adverse effects in the insects. The production of α-glycosidase inhibitors (AGIs) has been reported as an inherent mechanism in plants to resist herbivory and insect pests23–26. Transgenic plants expressing AGI genes have been produced and found to possess resistance against various insects27–29. Though, digestive enzyme inhibitors from plants have been extensively reported for their insecticidal activity23–26, there are few reports available of similar studies on bio control efficiency of enzyme inhibitors from endophytes. In this study, we evaluated the insecticidal potential of AGIs obtained from endophytic fungi against Spodoptera litura (Fab.). S. litura is a polyophagous lepidopteran pest causing huge ecomomic losses to variety of agriculturally important crops. Moreover, it has developed resistance to a number of commercially available insecticides6.

α-Glycosidase enzymes are also involved in processes during fungal growth and have a role in synthesis and extension of cell wall30. Inhibitors of such enzymes could affect the growth and development of fungi leading to antifungal activity. Keeping this in view, AGI potential of endophytic fungi isolated from Calotropis gigantea L. was used as a strategy for isolating potential strains with insecticidal and antifungal activity. Endophytes are known to produce compounds with similar properties as that of host plant through genetic recombination and vice versa31–33. C. gigantea was selected as it possesses, antifungal, antidiabetic and insecticidal potential34–36 and their endophytes might produce metabolites with α-glycosidase inhibitory activity.

Results

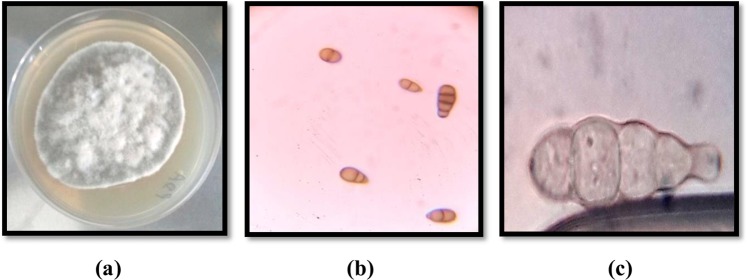

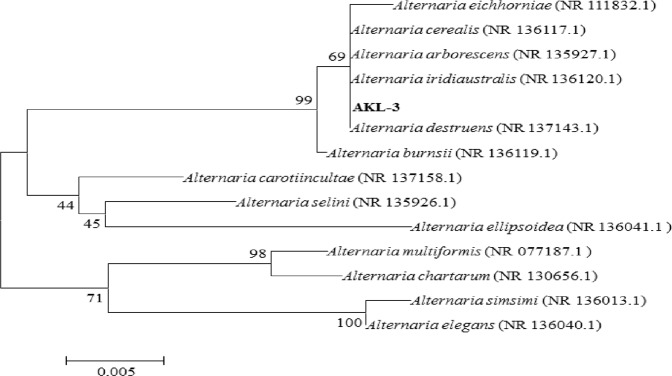

In the present study, 22 endophytic fungi were isolated from C. gigantea and screened for inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase and α-amylase. Six cultures exhibited α-glucosidase inhibitory activity in the range of 55–93.4% with maximum being found in AKL-3 (93.4%) followed by AKL-9 (84.4%). AKL-3 also inhibited α-amylase to the extent of 32% while other cultures did not show inhibition against α-amylase. Culture AKL-3 was selected for further studies and identified according to standard taxonomic key including colony diameter, color and morphology of hyphae and conidia. The colonies were slow growing having a diameter of 5.3 cm when incubated on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plates at 30 °C for 9 d. These were white in color when young and turned greenish on maturity with dark reverse (Fig. 1a). Hyphae were septate and branched in the apical region, conidia were multi-celled with transverse as well as longitudinal septa and round to oval in shape. Longitudinal septa were fewer in number than transverse septa (Fig. 1b,c). The genetic relationship of AKL-3 was determined by amplification of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA region. The size of the amplified sequence was 476 bp. After sequencing, the sequence was deposited with GenBank under accession number MH071380. Alignment with homologous nucleotide sequences, revealed the strain AKL-3 to be closest to Alternaria destruens with a similarity of 100% with type specimen (Fig. 2). Thus, on the basis of molecular and morphological analysis, the strain AKL-3 could be identified as A. destruens. The culture was submitted to National Centre for Microbial Resource (NCMR) at National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, Maharashtra, India under accession number MCC1666.

Figure 1.

Morphology of (a) colony and (b,c) conidia at 40X and 100X of A. destruens AKL-3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the position of AKL-3 on the basis of ITS1-5.8 rDNA-ITS2 gene sequence. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method. The analysis involved 14 nucleotide sequences. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. There were a total of 461 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 6.

Column chromatography of ethyl acetate extract of A. destruens AKL-3 yielded two active fractions (AF1 and AF2) which differed with respect to their color and also exhibited different TLC profiles. AF1 was yellow in color whereas AF2 was red. Active fraction AF1 inhibited α-glucosidase enzyme to an extent of 87.75% whereas AF2 showed 72.11% inhibition. Active fractions AF1 and AF2 were also assayed for their inhibitory potential against α-amylase and β-glucosidase. It was observed that AF1 was highly specific as it possessed α-glucosidase inhibitory potential but showed no inhibition against the other two enzymes (α-amylase and β-glucosidase), while active fraction AF2 exhibited inhibition against β-glucosidase (54.62%) as well as α-amylase (34.55%). Both the active fractions were found to possess phenolic compounds after staining with Fast Blue B and FeCl3.

Insecticidal activity

Preliminary studies to determine the insecticidal potential were carried out on second instar larvae of S. litura by feeding them on artificial diet supplemented with 1.5 mg/ml of AF1, AF2 and after pooling them together. The mean average larval mortality recorded was 19.99, 23.33 and 33.3 percent due to AF1, AF2 and pooled fraction, respectively. The effect of pooled fraction was more evident than the individual fractions therefore detailed studies on various parameters viz. larval mortality, larval period, pupal period and total development period were conducted using different concentrations (0.5–2.5 mg/ml) of pooled fraction.

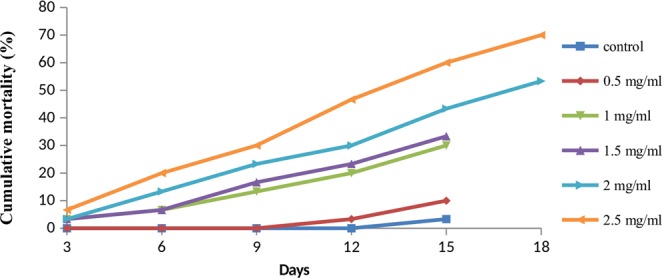

Larval exposure to diet amended with varying concentrations of pooled fraction of A. destruens resulted in total average mortality of 10 to 70 percent as compared to 3.33 percent in control. The larval mortality increased in a dose dependent manner with significant effect at 2.0 and 2.5 mg/ml (F = 13.55, p ≤ 0.001). The mortality rate increased steadily with the increase in feeding duration (Fig. 3). The LC50 value was determined to be 1.875 mg/ml using probit analysis. Sluggishness and failure of molting were observed prior to larval deaths (Fig. 4). The negative impact of the inhibitors was also observed on growth and developmental parameters of S. litura. Relative to control, the larval period extended significantly by 3.64 and 4.55 days due to 2.0 and 2.5 mg/ml of pooled fraction of A. destruens respectively (F = 41.92, p ≤ 0.001; Table 1). Similarly, the pupal period was also prolonged with significant effect at these two higher concentrations (F = 3.45, p ≤ 0.001). In comparison to control, the development period of S. litura was delayed by 7.89 and 9.19 days when the larvae consumed 2.0 and 2.5 mg/ml of partial purified inhibitor as evident in Table 1. Toxic effects of pooled fraction were also detected on adult emergence as 23.33 percent adults emerged at the highest concentration as compared to 96.67 percent in control.

Figure 3.

Mean cumulative mortality of second instar larvae of S. litura fed on diet supplemented with different concentrations of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3.

Figure 4.

Failure of molting in larva of S. litura due to α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3.

Table 1.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on larval mortality and development period of S. litura.

| Concentration (mg/ml) | Larval mortality (%) | Larval period (days) | Pupal period (days) | Total development period (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 03.33 ± 03.72a | 13.08 ± 0.17a | 8.73 ± 0.22a | 21.81 ± 0.25a |

| 0.5 | 10.00 ± 04.56a | 13.61 ± 0.29a | 8.82 ± 0.27a | 22.62 ± 0.35ab |

| 1.0 | 30.00 ± 05.56ab | 13.84 ± 0.25a | 10.00 ± 0.35ab | 24.40 ± 0.98bc |

| 1.5 | 33.33 ± 10.21ab | 13.39 ± 0.45a | 10.96 ± 0.35ab | 25.43 ± 0.84c |

| 2.0 | 53.33 ± 10.86bc | 16.72 ± 0.46b | 12.40 ± 0.27b | 29.70 ± 0.49d |

| 2.5 | 70.00 ± 06.97c | 17.63 ± 0.29b | 13.00 ± 0.0b | 31.00 ± 0.00d |

| F | 13.55** | 41.92** | 3.45* | 50.00** |

Values are Means ± S.E. Means followed by different superscript letters within a column are significantly different. Tukey’s test p ≤ 0.05. **Significant at 1%, *Significant at 5%.

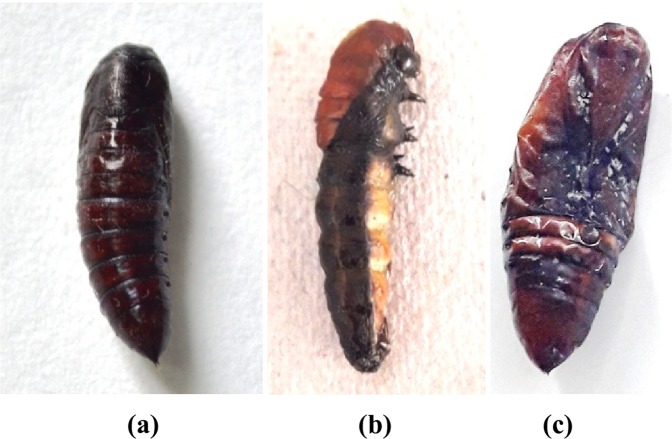

Sub lethal effects

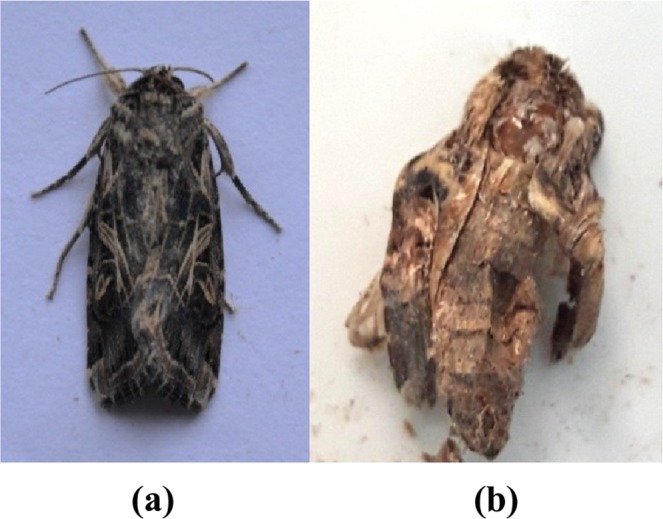

Sub lethal effects in the form of morphological deformities like larval pupal intermediates as well as pupae with attached larval exuviae, depressed head and unsclerotised cuticle were also manifested in S. litura (Fig. 5a–c). However, in some of the cases pupae were normal but the adults emerged with underdeveloped and crumpled wings (Fig. 6a,b).

Figure 5.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on pupae of S. litura (a) normal, (b) larval pupal intermediate, (c) deformed.

Figure 6.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on adults of S. litura (a) normal, (b) deformed.

Nutritional physiology

Nutritional analysis revealed a significant influence of pooled fraction of A. destruens AKL-3 culture on food utilization efficiency of S. litura (Table 2). A significant decline of 31.96–53.94 percent in relative growth rate (RGR) over control was recorded when fed on diet amended with different concentrations of the pooled fraction (F = 155.43, p ≤ 0.001). It was observed to be a dose dependent effect. Similarly, a significant decrease was recorded in relative consumption rate (RCR), which dropped by 19.24–72.93 percent over control at different concentrations (F = 442.51, p ≤ 0.001). The highest concentration of the inhibitor was found to be the most effective. Similar deleterious effects were observed in the efficiency of conversion of ingested (ECI) and digested food (ECD) of S. litura (ECI: F = 115.91, p ≤ 0.001; ECD: F = 255.66, p ≤ 0.001). The highest concentration exhibited maximum inhibitory effect by dropping the ECD by 2.85 times over control.

Table 2.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on nutritional physiology of S. litura larvae.

| Concentration (mg/ml) | RGR (mg/mg/day) | RCR (mg/mg/day) | ECI (%) | ECD (%) | AD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.94 ± 0.02a | 16.48 ± 0.35a | 7.42 ± 0.15a | 7.53 ± 0.16a | 99.68 ± 0.19 |

| 0.5 | 1.32 ± 0.05b | 13.31 ± 0.32b | 5.96 ± 0.30b | 6.09 ± 0.11b | 99.64 ± 0.15 |

| 1.0 | 1.25 ± 0.02b | 08.97 ± 0.18c | 4.67 ± 0.18c | 4.83 ± 0.11c | 99.62 ± 0.02 |

| 1.5 | 1.12 ± 0.04c | 07.42 ± 0.16d | 3.99 ± 0.07d | 4.09 ± 0.89d | 99.44 ± 0.55 |

| 2.0 | 1.08 ± 0.03c | 05.60 ± 2.18e | 3.49 ± 0.04de | 3.39 ± 0.09e | 99.29 ± 0.36 |

| 2.5 | 0.89 ± 0.02d | 04.45 ± 0.19f | 3.06 ± 0.16e | 2.64 ± 0.11f | 99.23 ± 0.04 |

| F | 155.43** | 442.51** | 115.91** | 255.66** | NS |

RGR = Relative growth rate, RCR = Relative consumption rate, ECI = Efficiency of conversion of ingested food, ECD = Efficiency of conversion of digested food, AD = Approximate digestibility. Values are Mean ± SE. Means followed by different superscript letters within a column are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) based on Tukey’s test. **Significant at 1%, NS non-significant.

In vivo effects on digestive enzymes

Addition of inhibitory fraction of A. destruens AKL-3 to larval diet significantly decreased α-glucosidase activity in the insect gut. As compared to control, there was 11.49–47.74 percent decline in the level of α-glucosidase activity after 48 hr (F = 262.34, p ≤ 0.001; Table 3). The larvae feeding on the highest concentration of pooled fraction showed 48.67 percent reduction in enzyme activity after 72 hr over control (F = 368.64, p ≤ 0.001). Similar effects were recorded on β-glucosidase. The decrease in enzyme activity was observed in the range of 18.96–42.06 percent after 48 hr (F = 135.46, p ≤ 0.001; Table 4). Although prolonged exposure to pooled fraction did not further drop the level of enzyme activity, but in comparison to control it remained significantly lower (F = 29.53, p ≤ 0.001). Pooled fraction also significantly suppressed the level of α-amylase of S. litura larvae. Larval exposure to amended diet for 48 hr reduced the α-amylase activity by 18.57–25.37 percent at higher concentrations (F = 36.29, p ≤ 0.001; Table 5) and 14.57–30.42 percent after 72 hr in comparison to control larvae (F = 104.73, p ≤ 0.001).

Table 3.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on α-glucosidase activity of S. litura larvae.

| α-Glucosidase activity (µmol/mg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/ml) | 48 hours | 72 hours |

| Control | 32.89 ± 1.09a | 40.35 ± 0.25a |

| 0.5 | 29.10 ± 0.42b | 38.54 ± 1.11a |

| 1.0 | 22.03 ± 0.43c | 34.62 ± 0.16b |

| 1.5 | 20.5 ± 0.08cd | 31.18 ± 0.21c |

| 2.0 | 19.26 ± 0.20de | 29.16 ± 0.21c |

| 2.5 | 17.18 ± 0.33e | 20.71 ± 0.50d |

| F | 262.34** | 368.64** |

Values are Mean ± SE. Means followed by different superscript letters within a column are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) based on Tukey’s test. **Significant at 1%.

Table 4.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on β-glucosidase activity of S. litura larvae.

| β-Glucosidase activity (µmol/mg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/ml) | 48 hours | 72 hours |

| Control | 37.28 ± 0.69a | 51.97 ± 2.16a |

| 0.5 | 30.21 ± 0.97b | 48.60 ± 2.54ab |

| 1.0 | 28.86 ± 0.52bc | 43.10 ± 0.28bc |

| 1.5 | 26.65 ± 0.06cd | 42.41 ± 0.07c |

| 2.0 | 24.52 ± 0.27d | 39.55 ± 0.19c |

| 2.5 | 21.60 ± 0.91e | 37.80 ± 0.79c |

| F | 135.46** | 29.53** |

Values are Mean ± SE. Means followed by different superscript letters within a column are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) based on Tukey’s test. **Significant at 1%.

Table 5.

Effect of α-glycosidase inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 on α-amylase activity of S. litura larvae.

| α-Amylase activity (µmol/mg) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/ml) | 48 hours | 72 hours |

| Control | 79.57 ± 0.86a | 88.90 ± 1.41a |

| 0.5 | 75.47 ± 2.91ab | 75.95 ± 2.31b |

| 1.0 | 74.11 ± 1.12ab | 70.33 ± 1.38c |

| 1.5 | 70.93 ± 0.79bc | 66.39 ± 0.52cd |

| 2.0 | 64.81 ± 1.71cd | 64.16 ± 0.92d |

| 2.5 | 59.38 ± 2.05d | 61.86 ± 0.97d |

| F | 36.29** | 104.73** |

Values are Mean ± SE. Means followed by different superscript letters within a column are significantly different (p ≤ 0.05) based on Tukey’s test. **Significant at 1%.

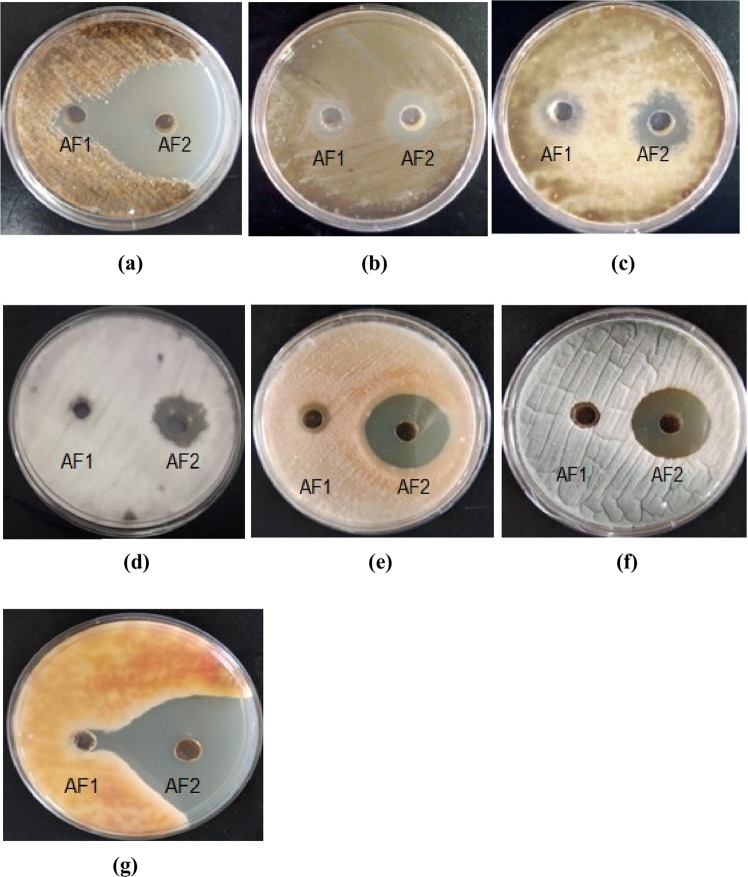

Antifungal activity

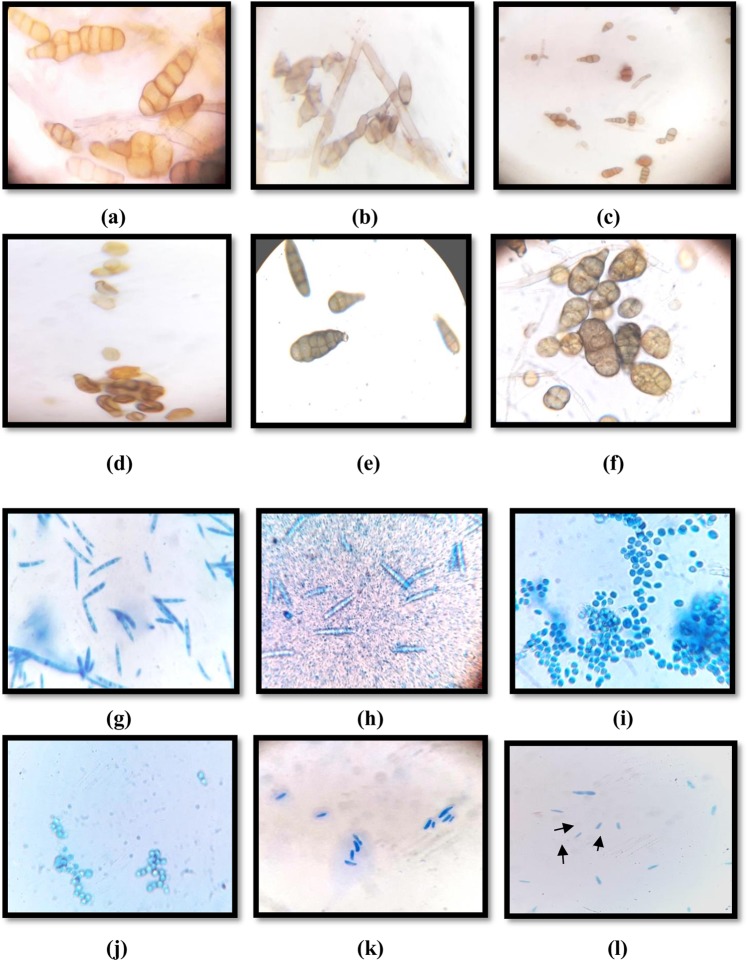

Both the active fractions of A. destruens AKL-3 were examined for their antifungal activity against phytopathogens. It was observed that active fraction AF2 was more potent in terms of its antifungal potential. Even at a lower concentration (250 µg/ml) it evinced higher antifungal activity as compared to AF1 (500 µg/ml). The fraction AF1 exhibited antagonist effect only against all tested Alternaria spp. and Cercospora beticola Sacc., producing inhibitory zones in the range of 10–11 mm whereas AF2 inhibited all the test pathogens producing higher zones of inhibition (22–44 mm) (Fig. 7a–g). The results of antifungal activity of AF2 prompted the examination of the spores and mycelial structures of the affected phytopathogens viz. Alternaria brassicicola (Schwein.) Wiltshire, Alternaria mali Roberts., Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissl., C. beticola, Cladosporium herbarum (Pers.) Link, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Sacc. and Fusarium oxysporum Schltdl.. Light microscopic studies demonstrated severe morphological abnormalities such as leakage of cellular material, thinning of hyphae, formation of vesicles, discoloration of hyphae and alteration in the spore morphology caused by metabolites near the inhibition zone. In A. brassicicola pronounced effects as manifested in mycelial breakage, deformed and shrunken spores and hyphal swellings resulting in bulbous structures were seen under light microscope (Fig. 8a,b). Shrunken and distorted spores were also observed in A. alternata and A. mali (Fig. 8c–f). No visible effects on hyphae were observed. In C. beticola and C. herbarum leakage of cytoplasmic content as well as morphological deformities were observed in spores as noticed in A. brassicicola. The treated spores were lightly stained as compared to untreated ones (Fig. 8g–j). In F. oxysporum reduction in the size of spores was observed (Fig. 8k,l).

Figure 7.

Zones of inhibition exhibited by active fractions AF1 and AF2 of A. destruens AKL-3 against different phytopathogenic fungi (a) A. brassicicola (b) A. alternata (c) A. mali (d) C. beticola (e) F. oxysporum (f) C. herbarum (g) C. gloeosporioides.

Figure 8.

Effect of active fraction AF2 of A. destruens AKL-3 on mycelial structure and spores of A. brassicicola (a: untreated, b: treated), A. alternata (c: untreated, d: treated), A. mali (e: untreated, f: treated), C. beticola (g: untreated, h: treated), C. herbarum (i: untreated, j: treated), F. oxysporum (k: untreated, l: treated).

Discussion

In the present study endophytes have been isolated from C. gigantea and screened for their α-glycosidase (α-glucosidase and α-amylase) inhibitory potential. Maximum α-glucosidase inhibitory potential was demonstrated by a culture AKL-3, identified to be Alternaria destruens. Although, a number of reports are available on endophytes with ability to produce α-glycosidase inhibitors37–42, this is the first study reporting the α-glycosidase inhibitory potential of an endophytic A. destruens. The isolate also exhibited good insecticidal and antifungal activity. A. destruens is a dothideomycetous fungus patented as a bioherbicide for controlling dodder species, a serious parasitic weed in the crops43, but no reports are available on its bio-control ability against insect pests and pathogens. Inhibitors of α-glycosidases have been recognized as inherent mechanisms of defense against insect pests23–25, but only a few reports are available on the insecticidal potential of digestive enzyme inhibitors from endophytic fungi40,42. Detrimental effects of α-glucosidase inhibitors produced by an endophytic Exophiala spinifera (Nielsen & Conant) McGinnis on S. litura have been documented by Kaur et al.42. In this study, partially purified AGIs from A. destruens were biochemically characterized as phenolic compounds after staining positively with Fast blue B and FeCl3. High larval mortality induced in the presence of inhibitory fraction could be attributed to phenolic nature of α-glycosidase inhibitory compounds. Detrimental effects of phenolic compounds on insect pests have been documented by Singh et al.44 and Singh et al.45. The AGI’s of A. destruens AKL-3 also delayed the overall development period. Delay in the development period of S. litura when fed on diet supplemented with phenolic compounds has been reported by other workers45,46. The molting process was also affected under the influence of A. destruens inhibitors, which caused morphological deformities like larval-pupal intermediates, undeveloped pupae and adults with underdeveloped and crumpled wings. It is possible that the AGIs obtained in the present study could be affecting the chitinase enzymes involved in the process of molting. Inhibitors of chitinase are known for their insecticidal activity47. Effect of inhibitors from A. destruens AKL-3 was also observed on nutritional analysis as it affected all the nutritional indices. Relative consumption and growth rate of larvae feeding on diet containing different concentrations of inhibitory compounds of A. destruens AKL-3 was also significantly reduced as compared to control. As consumption rate is directly proportional to growth rate, low consumption rate indicates antifeedant effects of the inhibitor. A decreased value of ECI indicated that food ingested was being mainly utilized for energy required for detoxification and less was being metabolized to insect biomass. With the increased requirement for energy, major proportion of digested food is utilized to fulfill energy requirement, hence lowering the ECD value. This diversion of energy from biomass production into detoxification reduces the growth48. Also, in vivo evaluation on S. litura’s digestive enzymes was carried out to determine whether the deleterious effects being observed under the influence of the inhibitors could be mediated by inhibiting digestive enzymes of insect. The in vivo studies corroborated the in vitro results and activity of all the tested digestive enzymes of S. litura was lowered to a significant level in in vivo studies. The inhibitory effects of phenolics on digestive enzymes have been reported in literature. Singh et al.45 reported the detrimental effects of chlorogenic acid isolated from an endophytic Cladosporium velox Zalar, de Hoog & Gunde-Cim., on digestive enzymes of S. litura. Karthik et al.49 isolated phenolics from the lichen Heterodermia leucomela (L.) Poelt (Caliciales: Physciaceae) and found them to inhibit digestive enzymes of mosquito Aedes aegypti L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Campbell et al.50 documented the inhibitory effects of an AGI castanospermine on disaccharide enzymes of sap feeding insects.

Glycosidase inhibitors have also been reported to possess antifungal activities51. Microscopic observations of phytopathogenic fungi treated with active fraction AF2 revealed severe detrimental effects on mycelium as well as on fungal spores. It is possible that inhibitory metabolites attack the cell wall as indicated by morphological alterations in vegetative cells and spores. As previously suggested they could be inhibiting the enzyme chitinase which is involved in processes during fungal growth and has a role in synthesis and extension of cell wall30. Therefore, glycosidase inhibitors can induce antifungal effects by affecting the chitinase enzymes52. In in vitro studies, it was determined that AF2 also possessed α-amylase and β-glucosidase inhibitory activities, which may be the contributing factors in increasing its antifungal activity. Kim et al.53 reported the antifungal activity of a β-glucosidase inhibitor which affected the hydrolytic enzymes of fungi.

Conclusion

This is the first report of α-glycosidase inhibitors from endophytic A. destruens. The study reveals the potential of endophytic fungi as sources of α-glycosidase inhibitors with insecticidal and antifungal potential. The present study also demonstrates that α-glycosidase inhibitory potential can be used as strategy for screening of endophytes with bio-control potential against pests and pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of endophytic fungi

Endophytic fungi were isolated from different parts viz. leaves and stems of healthy C. gigantea plants. After washing with running tap water, the plant parts were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water. Surface sterilization was carried out with 70% ethanol for 1–2 min followed by treatment with 4% sodium hypochlorite solution for 2–3 min. Again the plant parts were rinsed with sterilized distilled water. To ensure surface sterilization, the water obtained after last wash was plated on PDA. The plant parts (5–6 pieces) in the size range of 2–5 mm were inoculated on water agar plates supplemented with chloramphenicol (20 µg/ml) (HiMedia, Mumbai, India). Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 3–4 days to few weeks till the hyphae emerged. The emerging fungal hyphae from inoculated plant parts, were picked, purified and preserved on PDA slants for further studies42.

Production of secondary metabolites

The production was carried out in Erlenmeyer flasks (250 ml) containing 50 ml of malt extract broth (dextrose 2%, malt extract 2%, protease peptone 0.1%, pH 5.5)42. The production medium was inoculated with one plug (8 mm diameter) taken from periphery of freshly grown purified culture. The flasks were incubated for 10 days on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm and 30 °C. After 10 days of incubation, 50 ml ethyl acetate was added to each of the flask and extraction was carried out at 120 rpm and 40 °C for 1.5 hr twice. The extracted organic phase was concentrated on rotary evaporator (BUCHI). The concentrated samples were re-suspended in HPLC grade water and used for further studies.

Assay for α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase inhibition

Enzyme activity was determined in a microtiter 96-well plate. Reaction mixture consisting of 50 μl of phosphate buffer (50 mmol/l; pH 6.8), 10 μl of α-glucosidase enzyme (1U/ml) from Saccharomyces sp. (HiMedia) and 20 μl of inhibitory extract was pre-incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. After 5 min, 20 μl of 2 mmol/l pNPG substrate (HiMedia) (prepared in 50 mmol/l phosphate buffer, pH 6.8) was added followed by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Termination of reaction was carried out by addition of 50 μl of sodium carbonate (100 mmol/l)42. Acarbose was used as a positive control. The breakdown of pNPG into yellow coloured p-nitrophenol was quantified by reading the absorbance at 405 nm. Every experiment was performed in triplicate, along with appropriate blanks. The % inhibition was calculated using the formula:

For the determination of β-glucosidase inhibitory potential same procedure was applied using p-nitrophenyl–β-d-glucopyranoside as substrate.

Assay for α-amylase inhibition

The assay was conducted as described by Nair et al.54 with slight modification. The assay mixture containing 200 μl of 20 mmol/l sodium phosphate buffer, 40 μl of α-amylase enzyme from porcine pancreas (2 U/ml) (HiMedia) and 40 μl of fungal extract was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C, followed by addition of 50 μl of starch in all test tubes and further incubated for 20 min. The reaction was terminated with the addition of 500 μl DNS reagent and placed in boiling water bath for 5 min, cooled and diluted with 5 ml of distilled water. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm. The control samples were prepared without any fungal extract. Acarbose was used as positive control.

Identification of the producer culture

Selected culture was identified on the basis of morphological and molecular analysis. Morphological studies were conducted using slide culturing as described by Larone55. Thin layer PDA (potato dextrose agar) plates were prepared and small blocks were cut. These blocks were placed aseptically onto glass slide and inoculated with fungal culture. Coverslip was placed over it and incubated at 30 °C. The branching pattern, sporulation and arrangement of the hyphae were examined under microscope (OLYMPUS BX 60).

Phylogenetic analysis

The culture AKL-3 was identified on molecular basis by amplification of ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rDNA region using primer pair ITS1 and ITS4 by National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune (Maharashtra), India. Phylogenetic analysis of AKL-3 culture was conducted by NCCS, Pune.

Partial purification and biochemical analysis

For partial purification extract was loaded onto a silica gel (100–200 mesh size) column (2 × 25 cm). The solvent system used was chloroform: ethyl acetate: formic acid in 5:4:1 ratio. Using this solvent system, fractions of 10 ml each were collected and activity was observed in fraction no. 11 and 14 which were designated as AF1 and AF2, respectively. Chemical nature of active fractions was determined using various TLC based biochemical methods using different visualization reagents viz. Dragendroff’s reagent for alkaloids, FeCl3 and Fast Blue B for phenols, ninhydrin for amine group, p-anisaldehyde for the detection of steroids and terpenoids.

Insecticidal activity

Insect culture

Insecticidal activity was determined on larvae of S. litura. The culture was collected from fields around Amritsar (Punjab), India. It was reared on Ricinus communis L. (Euphorbiaceae) leaves in glass jars (15 × 10 cm) at 25 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5% relative humidity in the laboratory. Hygienic conditions were maintained by changing leaves regularly until pupation. The emerging pupae were separated and kept in pupation jars (15 × 10 cm) with 2–3 cm layer of moist sterilized sand covered with filter paper. The adult moths on emergence were transferred to oviposition jars in the ratio of (1:2) males and females|. For nourishment of adults, cotton swab dipped in water and honey solution (4:1) was provided daily as food. To facilitate egg laying the oviposition jars were lined with filter paper. On hatching larvae were maintained on artificial diet as recommended by Koul et al.56 with slight modifications.

Bioassay studies

Insecticidal potential of both active fractions (AF1 and AF2) of A. destruens AKL-3 was evaluated individually as well as after pooling them together, on S. litura at a concentration of 1.5 mg/ml. Pooled fraction of A. destruens AKL-3 induced significantly higher mortality than individual fractions. Therefore, detailed studies on various parameters viz. larval mortality, total development period were conducted using different concentrations (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5 mg/ml) of pooled fraction. Diet without inhibitor was taken as control. The experiment was designed randomly with six treatments including control and five replications per treatment. Six second instar larvae (6 days old) were taken per replication. Plastic containers (4 × 6 cm) were used to rear larvae individually on treated and control diets. The experiment was conducted under controlled temperature and humidity condition of 25 ± 2 °C and 65 ± 5%, respectively42. The diet was changed regularly on alternate days and larvae were checked daily for survival. Observations were made on larval mortality, larval period, pupal period as well as adult emergence. Furthermore, observations were recorded on morphological deformities in larvae, pupae and adults.

Nutritional analysis

The gravimetric method given by Waldbauer57 was used to determine the nutritional indices. For each concentration of inhibitor, twenty five second instar (6 days old) larvae were starved for 3–4 hr and fed on artificial diet amended with 0.5–2.5 mg/ml of inhibitor from A. destruens and unamended diet served as control. Larvae were maintained in plastic containers (4 × 6 cm) containing a known amount of diet. Optimum temperature and humidity of 25 ± 2 °C, and 65 ± 5%, respectively were maintained. After termination of experiment i.e. after 72 hr larvae, residual diet and faecal matter were separated, dried by incubation at 60 °C for 72 hr and weighed. All nutritional indices were calculated using dry weights and therefore 25 second instar larvae and 25 diet samples were dried to a constant weight to determine fresh/dry weight ratios58. Nutritional indices were calculated as per Wheelar and Isman59 by using following formulae:

RGR = Relative growth rate, RCR = Relative consumption rate, ECI = Efficiency of conversion of ingested food, ECD = Efficiency of conversion of digested food, AD = Approximate digestibility, d = day.

Effect on glycosidase enzymes of S. litura

To determine the activity of α-glucosidases, β-glucosidases and α-amylase in vivo, late second instar larvae were fed on a diet supplemented with different concentrations ranging from 0.5–2.5 mg/ml of the inhibitor as well as control diet for 48 hr and 72 hr. Ten larvae per replication were used for each time interval and the experiment was replicated thrice. Homogenates (1% w/v) were used as extracts and prepared by homogenizing larval midguts (25 mg) in 2.5 ml distilled water followed by transfer to 1.5 ml centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 13000 g for 20 min at 4 °C. α-Amylase and α-, β-glucosidase enzyme activities of homogenates were then assayed42.

Evaluation of antifungal activity

Antifungal activity was determined against various phytopathogens viz. A. brassicicola (MTCC 2102), A. mali (lab isolate), A. alternata (lab isolate), C. gloeosporioides (lab isolate), C. beticola (KJ461435), C. herbarum (MTCC 351), F. oxysporum (MTCC 284). Test fungi were inoculated on PDA plates and punctured with sterile cork borer to make wells (6 mm diameter). The inhibitor (200 µl) was transferred to each well under aseptic conditions and incubated at 30 °C for three days. The concentrations of inhibitors used were 250 µg/ml for AF2, 500 µg/ml for AF1. The antifungal activity was observed as clear zones of inhibition around wells and measured in millimeters (mm). The deformed hyphae of tested phytopathogens at zones of inhibition were picked and stained with lactophenol blue dye and examined under microscope for detection of morphological changes.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate except for bioassay studies were six replicates were taken. To compare difference in means, one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05 was performed. SPSS v17.0 software for windows version and Microsoft office excel 2007 (Microsoft Corp., USA) were used to perform the statistical analysis. The data on larval mortality was subjected to probit analysis for calculation of LC50 value.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies involving human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India for providing financial assistance.

Author Contributions

Amarjeet Kaur, Sanehdeep Kaur and Rajesh Kumari Manhas designed the study and analyzed the content. Jasleen Kaur and Avinash Sharma isolated the culture and performed all the insect based experiments. Manish Sharma performed the antifungal experiments and analyzed the content related to it. All authors read and approved the final manuscripts.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Oerke EC. Crop losses to pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006;144(1):31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhaliwal GS, Jindal V, Mohindru B. Crop losses due to insect pests: global and Indian scenario. Indian J. Entomol. 2015;77(2):165–168. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matny ON. Fusarium head blight and crown rot on wheat and barley: losses and health risks. Adv. Plant Agric. Res. 2015;2(39):10–15406. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shuping DSS, Eloff JN. The use of plants to protect plants and food against fungal pathogens: A review. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement Altern. Med. 2017;14(4):120. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i4.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kranthi KR, et al. Insecticide resistance in five major insect pests of cotton in India. Crop Prot. 2002;21(6):449–460. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmad M, Arif MI, Ahmad M. Occurrence of insecticide resistance in field populations of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Pakistan. Crop Prot. 2007;26(6):809–817. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz B, Boyle C. The endophytic continuum. Mycol. Res. 2005;109(6):661–686. doi: 10.1017/s095375620500273x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behie S, Zelisko P, Bidochka M. Endophytic insect-parasitic fungi translocate nitrogen directly from insects to plants. Science. 2012;336(6088):1576–1577. doi: 10.1126/science.1222289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behie SW, Bidochka MJ. Ubiquity of insect-derived nitrogen transfer to plants by endophytic insect-pathogenic fungi: an additional branch of the soil nitrogen cycle. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2014;80(5):1553–1560. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03338-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.González-Teuber M, Urzúa A, Morales A, Ibáñez C, Bascuñán-Godoy L. Benefits of a root fungal endophyte on physiological processes and growth of the vulnerable legume tree Prosopis chilensis (Fabaceae) J. Plant Ecol. 2018;12(2):264–271. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodriguez RJ, White JF, Jr., Arnold AE, Redman ARA. Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. New Phytol. 2009;182(2):314–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lata R, Chowdhury S, Gond SK, White JF., Jr. Induction of abiotic stress tolerance in plants by endophytic microbes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;66(4):268–276. doi: 10.1111/lam.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S, Kaushik N. Endophytic fungi isolated from oil-seed crop Jatropha curcas produces oil and exhibit antifungal activity. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e56202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sánchez-Rodríguez AR, et al. An endophytic Beauveria bassiana strain increases spike production in bread and durum wheat plants and effectively controls cotton leafworm (Spodoptera littoralis) larvae. Biol. Control. 2018;116:90–102. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiba T, Sugawara K. Inhibitory effect of an endophytic fungus, Neotyphodium lolii, on the feeding and survival of Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenee)(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) and Sesamia inferens (Walker)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on infected Lolium perenne. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 2010;45(1):225–231. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menjivar RD, Cabrera JA, Kranz J, Sikora RA. Induction of metabolite organic compounds by mutualistic endophytic fungi to reduce the greenhouse whitefly Trialeurodes vaporariorum (Westwood) infection on tomato. Plant Soil. 2012;352(1-2):233–241. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan RX, Zou WX. Endophytes: a rich source of functional metabolites. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001;18(4):448–459. doi: 10.1039/b100918o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breen JP. Enhanced resistance to fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Acremonium endophyte-infected turf grasses. J. Econ. Entomol. 1993;86(2):621–629. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azevedo JL, Maccheroni W, Jr., Periera JO, Araujo WL. Endophytic microorganisms: A review on insect control and recent advances on tropical plants. Electron J. Biotechn. 2000;3(1):40–65. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudgers JA, Clay K. An invasive plant-fungal mutualism reduces arthropod diversity. Ecol. Lett. 2008;11(8):831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall BG, Pikis A, Thompson J. Evolution and biochemistry of family 4 glycosidases: Implications for assigning enzyme function in sequence annotations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009;26(11):2487–2497. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asadi A, Ghadamyari M, Sajedi RH, Sendi JJ, Tabari M. Biochemical characterization of α-and β-glucosidases in alimentary canal, salivary glands and haemolymph of the rice green caterpillar, Naranga aenescens M.(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Biologia. 2012;67(6):1186–1194. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franco OL, Rigden DJ, Melo FR, Grossi de Sa MF. Plant α-amylase inhibitors and their interaction with insect α-amylases structure, function and potential for crop protection. Euro. J. Biochem. 2002;269(2):397–412. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esmaeily M, Bandani AR. Interaction between larval α-amylase of the tomato leaf miner, Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) and proteinaceous extracts from plant seeds. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2015;55(3):278–286. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esmaeily M, Bandani AR, Farahani S, Amini S. Effect of seed proteinaceous extracts on α-amylase activity of carob moth, Ectomyelois ceratoniae Zeller (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2016;4(4):129–134. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nash RJ, Fenton KA, Gatehouse AMR, Bell EA. Effects of the plant alkaloid castanospermine as an antimetabolite of storage pests. Entomol. Exper. Appl. 1986;42(1):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shade RE, et al. Transgenic pea seeds expressing the α-amylase inhibitor of the common bean are resistant to bruchid beetles. Nat. Biotechnol. 1994;12(8):793–796. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbosa AE, et al. α-Amylase inhibitor-1 gene from Phaseolus vulgaris expressed in Coffea arabica plants inhibits α-amylases from the coffee berry borer pest. BMC Biotechnol. 2010;10(1):44. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lüthi C, et al. Potential of the bean α‐amylase inhibitor αAI‐1 to inhibit α‐amylase activity in true bugs (Hemiptera) J. Appl. Entomol. 2015;139(3):192–200. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seidl V. Chitinases of filamentous fungi: a large group of diverse proteins with multiple physiological functions. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2008;22(1):36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stierle A, Strobel G, Stierle D. Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science. 1993;260(5105):214–216. doi: 10.1126/science.8097061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puri SC, Verma V, Amna T, Qazi GN, Spiteller M. An endophytic fungus from Nothapodytes foetida that produces camptothecin. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68(12):1717–1719. doi: 10.1021/np0502802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kusari S, Verma VC, Lamshoeft M, Spiteller M. An endophytic fungus from Azadirachta indica A. Juss. that produces azadirachtin. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28(3):1287–1294. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0876-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.David M, Kumar R, Bhavani M. Experimental studies on active metabolites of Calotropis gigantea for evaluation of possible antifungal properties. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2013;4(5):250–254. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manivannan R, Shopna R. Antidiabetic activity of Calotropis gigantea white flower extracts in alloxan induced diabetic rats. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2017;7(3):106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kovendan K, et al. Mosquitocidal properties of Calotropis gigantea (Family: Asclepiadaceae) leaf extract and bacterial insecticide, Bacillus thuringiensis, against the mosquito vectors. Parasitol. Res. 2012;111(2):531–544. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-2865-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mun’im A, Ramdhan MG, Soemiati A. Screening of endophytic fungi from Cassia siamea Lamk leaves as α-glucosidase inhibitor. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2013;4(5):128–131. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramdanis R, Soemiati A, Mun’im A. Isolation and alpha glucosidase inhibitory activity of endophytic fungi from mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla king) seeds. Int. J. Med. Aromat. Plants. 2012;2(3):447–452. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh B, Kaur A. Antidiabetic potential of a peptide isolated from an endophytic Aspergillus awamori. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015;120(2):301–311. doi: 10.1111/jam.12998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh B, Kaur T, Kaur S, Manhas RK, Kaur A. Insecticidal potential of an endophytic Cladosporium velox against Spodoptera litura mediated through inhibition of alpha glycosidases. Pest Bioch. Physiol. 2016;131:46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centko RM, et al. Alpha-glucosidase and alpha-amylase inhibiting thiodiketopiperazines from the endophytic fungus Setosphaeria rostrata isolated from the medicinal plant Costus speciosus in Sri Lanka. Phytochem. Lett. 2017;22:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaur J, Kaur R, Dutta R, Kaur S, Kaur A. Exploration of insecticidal potential of an alpha glucosidase enzyme inhibitor from an endophytic Exophiala spinifera. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018;125(5):1455–1465. doi: 10.1111/jam.13947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cook JC, et al. Effects of Alternaria destruens, glyphosate, and ammonium sulfate individually and integrated for control of dodder (Cuscuta pentagona) Weed technol. 2009;23(4):550–555. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh H, Dixit S, Verma PC, Singh PK. Evaluation of total phenolic compounds and insecticidal and antioxidant activities of tomato hairy root extract. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(12):2588–2594. doi: 10.1021/jf405695y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh B, Kaur T, Kaur S, Manhas RK, Kaur A. An alpha-glucosidase inhibitor from an endophytic Cladosporium sp. with potential as a biocontrol agent. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015;175(4):2020–2034. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-1325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva TRFB, et al. Effect of the flavonoid rutin on the biology of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Acta. Sci. Agron. 2016;38(2):165–170. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saguez J, Vincent C, Giordanengo P. Chitinase inhibitors and chitin mimetics for crop protection. Pest Technol. 2008;2(2):81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senthil-Nathan S, Kalaivani K. Efficacy of nucleo polyhedron virus (NPV) and azadirachtin on Spodoptera litura Fabricius (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Biol. Control. 2005;34:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karthik S, Nandini KC, Kekuda TRP, Vinayaka KS, Mukunda S. Total phenol content, insecticidal and amylase inhibitory efficacy of Heterodermia leucomela (L) Ann. Biol. Res. 2011;2(4):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campbell BC, Molyneux RJ, Jones KC. Differential inhibition by castanospermine of various insect disaccharidases. J. Chem. Ecol. 1987;13(7):1759–1770. doi: 10.1007/BF00980216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asano N. Glycosidase inhibitors: update and perspectives on practical use. Glycobiology. 2003;13(10):93R–104R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bortone K, Monzingo AF, Ernst S, Robertus JD. The structure of an allosamidin complex with the Coccidioides immitis defines a role for second acid residue in substrate-assisted mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320(2):293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00444-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim KJ, Yang YJ, Kim J. Production of α-glucosidase inhibitor by β-glucosidase inhibitor producing Bacillus lentimorbus B-6. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;12(6):895–900. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nair SS, Kavrekar V, Mishra A. In vitro studies on alpha amylase and alpha glucosidase inhibitory activities of selected plant extracts. Euro. J. Exp. Bio. 2013;3(1):128–132. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larone, D. H. Medically important fungi: a guide to identification. Washington, DC: ASM press (2002).

- 56.Koul O, et al. Bioefficacy of crude extracts of Aglaia species (Meliaceae) and some active fractions against lepidopteran larvae. J. Appl. Entomol. 1997;121(1-5):245–248. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Waldbauer GP. The consumption and utilization of food by insects. Adv. Insect. Physiol. 1968;5:229–288. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farrar RR, Barbour JD, Kennedy GG. Quantifying food consumption and growth in insects. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1989;82(5):593–598. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wheeler DA, Isman MB. Antifeedant and toxic activity of Trichilia americana extract against the larvae of Spodoptera litura. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2001;98(1):9–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.