Abstract

Head and neck angiosarcomas (HN-AS) are rare malignancies with a poor prognosis relative to other soft tissue sarcomas. To date, the HN-AS literature has been limited to short reports and single-institution experiences. This study evaluated patients registered with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program who had been diagnosed with a primary HN-AS. Predictors were drawn from demographic and baseline tumor characteristics. Outcomes were survival months and cause of death. Kaplan–Meier analyses were used to estimate overall (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) rates. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used for multivariate analyses. A total of 1250 patients (mean age 73.3 years) were identified, and nearly all lesions (93.5%) were cutaneous. Two- and 5-year OS rates were 47.3% (95% CI 44.3–50.3) and 26.5% (95% CI 23.7–29.3), while 2- and 5-year DSS rates were 66.6% (95% CI 63.6–69.6) and 48.3% (95% CI 44.5–52.1). In the univariate analyses, age, race, tumor grade, tumor size, AJCC stage, SEER historic stage, and surgery were significant predictors of both OS and DSS. Multivariate regression revealed that independent predictors of poor OS and DSS were older age [OS: HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.02–1.05), p < 0.01; DSS: HR 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05), p < 0.01], increased tumor size [OS: HR 1.01 (95% CI 1.01–1.01), p < 0.01; DSS: HR 1.01 (95% CI 1.01–1.02), p < 0.01], and distant disease [OS: HR 2.97 (95% CI 1.65–5.34), p < 0.01; DSS: HR 4.99 (95% CI 2.50–9.98), p < 0.01]. Age, tumor size, and disease extent were determinants of HN-AS survival. When all other factors were controlled, lower histologic grade and surgery did not improve the risk of death.

Keywords: Angiosarcoma, Head and neck malignancy, Population data, Survival analysis

Introduction

Angiosarcomas (AS) are a family of aggressive malignancies that demonstrate vascular endothelial cell differentiation. The majority of AS occur spontaneously, however proven risk factors include radiation [1], chronic lymphedema as part of Stewart-Treves syndrome [2], and chemical exposures [3]. Tumors may arise within any anatomic location but the most common primary sites are the skin of the head and neck and the breast [4]. Head and neck AS (HN-AS) classically occurs on the scalp of older Caucasian men, mimicking either a bruise or a benign hemangioma [5]. Local recurrence rates are high because multifocal extension makes obtaining negative margins difficult. In addition, AS follows a relatively subclinical course, and this diagnostic challenge coupled with the tendency for local recurrence contributes to a significantly poorer overall survival rate when compared to that of other sarcomas [6].

AS is a rare lesion with an estimated annual incidence of 200 new cases per year in the United States [5, 7]. As a result, few studies other than case reports and single-institutional experiences have comprehensively described its clinical features, treatment, and prognosis [5]. When discussing AS, primary location has been shown to affect the characteristics, behaviors, and prognosis [4]. HN-AS have the worst survival rates [8, 9], and although the head and neck region is commonly affected [4], the paucity of cases makes studying this subset of tumors increasingly difficult.

This retrospective analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry represents the largest AS cohort in the literature to date. The purpose of this study was to describe the characteristics of and determine the prognostic factors associated with primary HN-AS. To achieve our aims, patient demographics and tumor characteristics at the time of diagnosis were reported and evaluated against the outcomes of overall and disease-specific survival.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

This study evaluated patients registered with the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program who were diagnosed with a primary angiosarcoma of the head and neck region. The SEER program of the National Cancer Institute is a nationwide coordinated system of cancer registries. The SEER 18 database was used for this study and includes cases recorded between 1973 and 2015 spanning 18 different US geographic areas that encompass roughly 27.8% of the US population. Institutional review board approval was not required for this study because all patient information is de-identified and publicly available.

Patient Selection and Variables

Patients were included if they had been diagnosed with a primary HN-AS. Lesions within the central nervous system and orbits were excluded. Angiosarcoma was defined using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3) morphological code 9120/3. The search was limited to the head and neck region using the ICD-O-3 topographical codes: C00-C14; C30-C33; C41.0; C41.1; C44.0-4; C47.0; C49.0; C76.0; C77.0. Baseline variables were recorded regarding age at diagnosis, gender, race, marital status, tumor grade, tumor size, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, SEER historic stage, and location. Tumor grade was classified as either grade I well differentiated; grade II moderately differentiated; grade III poorly differentiated; or grade IV undifferentiated. As in prior studies [10–13], grades I and II were considered low grade, and grades III and IV were considered high grade. Grade, as reported through SEER, was determined by the reporting pathologist for each lesion. There are no universal criteria for grading AS, and final classification relies on both visual inspection and objective criteria that were not disclosed. Tumor size was determined using the length of the largest dimension. A value of ≥ 5 cm was used as the threshold for large size, and this cutoff was adopted from the AJCC TNM criteria. AJCC stage was derived from the AJCC 6th edition and was defined as either stage 1, 2, 3, or 4 as assigned by the TNM grouping for soft tissue sarcomas. For cases before 2004, AJCC stage was retroactively determined using collaborative stage and extent of disease staging codes for tumor size, extent, and lymph node involvement. SEER historic stage is based on categories developed by the End Results Group of National Cancer Institute (NCI) and was classified as localized, regional, or distant. Localized was defined as being confined completely within the organ, regional was defined as extending beyond the limits of the primary organ into surrounding organs, tissues, and/or lymph nodes, and distant was defined as spreading either by direct extension or discontinuous metastasis to distant organs, tissues, or via the lymphatic system to distant lymph nodes. Location was divided between cutaneous and non-cutaneous sites. Outcome variables were recorded regarding survival months and cause of death. Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from diagnosis to death of any cause. Disease-specific survival (DSS) was defined as time from diagnosis to death caused by AS diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all baseline variables. Kaplan–Meier analyses were used to plot survival and estimate 1-, 2-, 5-, and 10-year overall and disease-specific survival rates. The log-rank test was used to perform univariate analyses and test differences in survival. Predictors for the multivariate model were chosen from those factors identified in the univariate analysis to be statistically significant. Because AJCC stage is derived from related information already contained within tumor size and SEER histologic stage, it was not included as a predictor in the final model in order to avoid issues of multicollinearity. Cox proportional hazards regression models were taken to perform multivariate analyses. Hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated and their significance was determined using the Wald Chi square test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all analyses were performed with SAS® software version 9.4 (2002–2012, Cary NC).

Results

Descriptive

During the period between 1973 and 2015, there were 1250 patients in the SEER 18 database who had a diagnosis of a primary HN-AS. The mean age of diagnosis was 73.3 years (range 0–102), and roughly two-thirds of the sample was over 70 at the time of diagnosis. With respect to gender, 68.6% were male and 31.4% were female (Table 1). Eighty-five percent were white, 5.3% black, and 9.2% other.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and tumor characteristics for head and neck angiosarcomas diagnosed between 1973–2015

| N, number | %, percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 1250 | 100 |

| Age at diagnosis, years (mean ± SD) | 73.3 ± 14.0 | |

| Age groups | ||

| 0–19 | 6 | 0.48 |

| 20–29 | 11 | 0.88 |

| 30–39 | 16 | 1.3 |

| 40–49 | 40 | 3.2 |

| 50–59 | 113 | 9.0 |

| 60–69 | 205 | 16.4 |

| 70–79 | 389 | 31.1 |

| 80+ | 470 | 37.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 857 | 68.6 |

| Female | 393 | 31.4 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1055 | 85.5 |

| Black | 66 | 5.3 |

| Other | 113 | 9.2 |

| Not recorded | 16 | - |

| Location | ||

| Cutaneous | 1169 | 93.5 |

| Non-cutaneous | 81 | 6.5 |

| Size | ||

| Largest dimension, cm (mean ± SD) | 4.9 ± 7.3 | |

| 5 cm | 313 | 66.0 |

| 5 cm | 161 | 34.0 |

| Not recorded | 776 | – |

| Histologic grade | ||

| Grade I: well differentiated | 58 | 10.8 |

| Grade II: moderately differentiated | 96 | 17.9 |

| Grade III: poorly differentiated | 204 | 38.1 |

| Grade IV: undifferentiated/anaplastic | 177 | 33.1 |

| Not recorded | 715 | – |

| AJCC stage | ||

| Stage 1 | 31 | 18.0 |

| Stage 2 | 53 | 30.8 |

| Stage 3 | 16 | 9.3 |

| Stage 4 | 72 | 41.9 |

| Not recorded | 1078 | – |

| SEER historic stage | ||

| Localized | 617 | 57.7 |

| Regional | 319 | 29.8 |

| Distant | 134 | 12.5 |

| Not recorded | 180 | – |

AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer, SEER Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

Nearly all lesions were cutaneous (n = 1169, 93.5%). Of the remaining 81 non-cutaneous lesions, 12 were located within the facial bones; 11 on the tongue; 10 within the nasal cavity; 9 within the parotid; 8 within the paranasal sinuses; 8 on either the buccal mucosa, gums, or mouth not otherwise specified; 8 within either the nasopharynx, oropharynx, or pharynx not otherwise specified; 7 within the larynx; 5 on the palate; and 3 arose on the peripheral nerves. The average tumor size was 4.9 cm (range 0.1–98.9) with 66% being less than 5 cm at the largest dimension. The distribution of histological grades was grade III poorly differentiated (38.1%), grade IV undifferentiated (33.1%), grade II moderately differentiated (17.9%), and grade I well differentiated (10.8%). The majority of lesions were localized to their primary site (57.7%) with less lesions demonstrating regional (29.8%) or distant (12.5%) invasion. Among those with AJCC staging available, 41.9% were stage 4, 30.8% stage 2, 18% stage 1, and 9.6% stage 3.

Survival

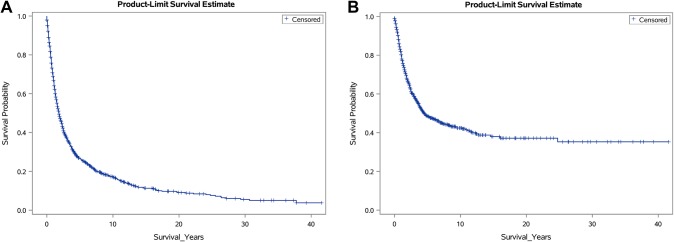

The mean length of follow-up was 40.0 months (range 0–499), and 315 (25.2%) patients were reported alive at their last follow-up. Overall 1-, 2-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates were 66.9% (95% CI 64.1–69.7), 47.3% (95% CI 44.3–50.3), 26.5% (95% CI 23.7–29.3), 16.9% (95% CI 14.3–19.5) respectively (Table 2) (Fig. 1a). The median OS time was 1.8 years (95% CI 1.7–2.1). Among the 935 patients who died, 476 (50.9%) had cause-specific deaths attributable to their AS diagnosis. Disease-specific 1-, 2-, 5-, and 10-year survival rates were 80.2% (95% CI 77.8–82.6), 66.6% (95% CI 63.6–69.6), 48.3% (95% CI 44.5–52.1), and 42.0% (95% CI 37.8–46.2) respectively (Table 2) (Fig. 1b). The median DSS time was 4.5 years (95% CI 3.8–6.4).

Table 2.

Overall survival and disease-specific survival as estimated by Kaplan–Meier analyses

| 1-year, % (95% CI) |

2-year, % (95% CI) |

5-year, % (95% CI) |

10-year, % (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival, OS | 66.9 (64.1–69.7) | 47.3 (44.3–50.3) | 26.5 (23.7–29.3) | 16.9 (14.3–19.5) |

| Disease-specific survival, DSS | 80.2 (77.8–82.6) | 66.6 (63.6–69.6) | 48.3 (44.5–52.1) | 42.0 (37.8–46.2) |

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival plots for patients with head and neck angiosarcomas showing a overall survival (OS) and b disease-specific survival (DSS)

In the univariate analyses, age (p < 0.01), race (p < 0.01), tumor grade (p < 0.01), tumor size (p < 0.01), AJCC stage (p < 0.01), SEER historic stage (p < 0.01), and surgery (p < 0.01) were all predictors of both OS and DSS (Table 3). Gender (p < 0.01) and lesion location (p = 0.03) were predictors of DSS only.

Table 3.

Univariate analyses for overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients with angiosarcoma of the head and neck diagnosed between 1973–2015

| 2-year DSS, % (95% CI) |

5-year DSS, % (95% CI) |

p-value* | 2-year OS, % (95% CI) |

5-year OS, % (95% CI) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| 70 | 77.1 (72.3–81.9) | 60.8(54.8–66.8) | 65.3 (60.3–70.3) | 45.3 (39.7–50.9) | ||

| 70 | 61.3 (57.3–65.3) | 40.3 (35.3–45.3) | 39.0 (35.4–42.6) | 17.3 (14.3–20.3) | ||

| Race | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| White | 70.1 (66.9–73.3) | 50.3 (46.1–54.5) | 49.7 (46.5–52.9) | 27.8 (24.8–30.8) | ||

| Non-white | 43.4 (34.6–52.2) | 32.1 (22.7–41.5) | 30.2 (23.0–37.4) | 16.1 (10.1–22.1) | ||

| Gender | < 0.01** | 0.13 | ||||

| Male | 70.1 (66.5–73.7) | 53.2 (48.6–57.8) | 49.2 (45.6–52.8) | 28.8 (25.4–32.3) | ||

| Female | 59.1 (53.5–64.7) | 37.8 (31.4–44.2) | 43.2 (38.0–48.4) | 21.6 (17.0–26.2) | ||

| Location | 0.03** | 0.25 | ||||

| Cutaneous | 66.2 (63.0–69.4) | 47.3 (43.5–51.1) | 47.4 (44.4–50.4) | 26.4 (23.6–29.2) | ||

| Not cutaneous | 70.7 (58.7–82.7) | – | 42.3 (30.7–53.9) | 26.2 (15.0–37.4) | ||

| Grade | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| Low | 73.1 (64.9–81.3) | 55.1 (44.5–65.7) | 53.7 (45.3–62.1) | 31.1 (22.7–39.5) | ||

| High | 67.0 (61.6–72.4) | 41.0 (34.0–48.0) | 50.1 (44.7–55.5) | 21.7 (16.9–26.5) | ||

| Tumor size, cm | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| 5 | 82.1 (76.9–87.3) | 58.2 (49.2–67.2) | 58.0 (52.0–64.0) | 32.3 (25.7–38.9) | ||

| 5 | 47.3 (37.7–56.9) | 15.5 (3.5–27.5) | 32.0 (24.0–40.0) | 5.7 (0.70–10.7) | ||

| AJCC stage | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| Stage 1 or 2 | 74.1 (62.9–85.3) | 42.4 (24.8–60.0) | 57.0 (45.2–68.8) | 27.4 (15.0–39.8) | ||

| Stage 3 or 4 | 41.5 (28.7–54.3) | 12.1 (1.7–25.9) | 31.5 (20.5–42.5) | 6.6 (− 1.2 to 14.4) | ||

| SEER historic stage | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| Localized | 73.3 (69.3–77.3) | 58.3 (50.1–63.5) | 55.2 (51.0–59.4) | 34.2 (30.0–38.4) | ||

| Regional | 63.3 (57.3–69.3) | 39.4 (32.2–46.6) | 47.5 (41.7–53.3) | 21.6 (16.6–26.6) | ||

| Distant | 25.5 (15.5–35.5) | 5.8 (− 3.6 to 15.2) | 12.8 (6.6–19.0) | 3.9 (− 0.3 to 8.1) | ||

| Surgery | < 0.01** | < 0.01** | ||||

| Yes | 72.1 (68.1–76.1) | 49.3 (43.9–54.7) | 52.6 (48.4–56.8) | 28.0 (24.0–32.0) | ||

| No | 56.9 (50.1–63.7) | 35.4 (26.6–44.2) | 33.1 (27.5–38.7) | 13.6 (9.0–18.2) |

OS overall survival, DSS disease-specific survival

*By the log-rank test

**p < 0.05

The multivariate models (Table 4) conducted for both OS and DSS included the predictors of age as a continuous variable, gender, race, tumor size as a continuous variable, histologic grade, SEER stage, and surgery. Older age [OS: HR 1.04 (95% CI 1.02–1.05), p < 0.01; DSS: HR 1.03 (95% CI 1.01–1.05), p < 0.01], increased tumor size [OS: HR 1.01 (95% CI 1.01–1.01), p < 0.01; DSS: HR 1.01 (95% CI 1.01–1.02), p < 0.01], and distant disease [OS: HR 2.97 (95% CI 1.65–5.34), p < 0.01; DSS: HR 4.99 (95% CI 2.50–9.98), p < 0.01] all independently increased the risk of both overall and disease-specific death. Regional disease [DSS: HR 0.59 (95% CI 0.36–0.97), p = 0.04] was found to reduce the risk of disease-specific death relative to localized disease.

Table 4.

Cox proportions hazards models for multivariate analyses of overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients with angiosarcoma of the head and neck diagnosed between 1973–2015

| DSS | OS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

p-value* | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

p-value* | |

| Age, years | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | < 0.01** | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | < 0.01** |

| Gender | 0.83 | 0.33 | ||

| Male | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Female | 0.95 (0.59–1.52) | 0.84 (0.59–1.20) | ||

| Race | 0.15 | 0.32 | ||

| White | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Non-white | 1.48 (0.87–2.50) | 1.24 (0.81–1.90) | ||

| Tumor size, mm | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | < 0.01** | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | < 0.01** |

| Grade | 0.37 | 0.57 | ||

| Low | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| High | 1.28 (0.75–2.19) | 1.12 (0.76–1.64) | ||

| SEER historic stage | ||||

| Localized | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Regional | 0.59 (0.36–0.97) | 0.04** | 0.72 (0.50–1.05) | 0.08 |

| Distant | 4.99 (2.50–9.98) | < 0.01** | 2.97 (1.65–5.34) | < 0.01** |

| Surgery | 0.14 | 0.20 | ||

| Yes | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| No | 1.61 (0.86–3.00) | 1.39 (0.84–2.29) | ||

OS overall survival, DSS disease-specific survival, Ref reference value

*By the Wald Chi square test

**p < 0.05

Gender [OS: 0.84 (95% CI 0.59–1.20), p = 0.33; DSS: 0.95 (95% CI 0.59–1.52), p = 0.83], race [OS: 1.24 (95% CI 0.81–1.90), p = 0.32; DSS: 1.48 (95% CI 0.87–2.50), p = 0.15], surgery [OS: 1.39 (95% CI 0.84–2.29), p = 0.20; DSS: 1.61 (95% CI 0.86–3.00), p = 0.14], and histologic grade [OS: 1.12 (95% CI 0.76–1.64), p = 0.57; DSS: 1.28 (95% CI 0.75–2.19), p = 0.37], when all other predictors are controlled for, did not significantly improve the risk of overall or disease-specific death at any given time point.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to report on the clinicopathologic characteristics and survival outcomes of HN-AS. Our results found that nearly all (93.5%) of the HN-AS were cutaneous (cHN-AS). Demographic characteristics showed a mean age of 73.3 with a greater proportion of white (85.5%) male (68.6%) patients. Lesions were more frequently smaller than 5 cm (66%) and poorly differentiated (38.1%). The sample was divided almost evenly between those with localized disease (57.7%) and those with disease involving the regional lymph nodes and/or distant sites (41.9%). Survival rates were generally poor with a 5-year OS and DSS of 26.5% and 48.3% respectively. In the univariate analyses, both DSS and OS were significantly improved in whites, males, those younger than 70, and those who received surgery either alone or as part of multimodal therapy. Likewise, favorable tumor characteristics such as non-cutaneous location, lower grade, lower AJCC stage, and decreased size were found to have significantly better OS and DSS. In the multivariate analyses, age, tumor size, and the presence of distant disease all were independent predictors of both OS and DSS. Every 1 year increase in age at diagnosis increased the risks of overall and disease-specific death by 3.8 and 3.1% respectively. Every 1 mm increase in tumor size increased the risks of overall and disease-specific death by 0.9 and 1.2%. The presence of distant disease, relative to localized disease, increased the risks of overall and disease-specific death by 197 and 399%. Interestingly, regional, compared to localized, disease had a 41.1% reduction in disease-specific survival. Because AS is often multifocal, diseases classified as localized may in fact fail to detect regional or even distant involvement when present. A diagnosis of regional disease may have a better specificity allowing for early and appropriate management of those identified cases. When all other predictors were controlled for, surgery and histologic grade were not found to alter either OS or DSS.

In our sample we found that the vast majority of HN-AS were cHN-AS, and this distribution agrees with what has been reported in past studies. Mark et al. surveyed 28 HN-AS of which 25 (89.3%) were cutaneous [14]. Likewise, 6 (75%) of the 8 HN-AS cases presented by Mullins et al. were cutaneous [15]. Among cHN-AS, multiple reports agree that the scalp is the most likely region affected [4, 9, 13, 14, 16, 17]. The 5- and 10-year relative survival rates of cHN-AS are worse than that of other cutaneous sites [9], with scalp primaries noted to have a worse survival than those arising on the face [10, 12, 17, 18]. The reasons for these findings are unknown, however there is an increased rate of positive margins in cHN-AS [8], and the improved survival at other sites may be due to an enhanced ability to perform wider resections with less reconstruction concerns. Previous studies evaluating cHN-AS reported 3-year and 5-year OS rates of 31–71% [6, 10, 11] and 12–43% [6, 10, 12, 13, 17] respectively. We determined a 5-year OS survival rate of 26.5% (95% CI 23.7–29.3) which is at the lower end of what was previously reported for cHN-AS. Our figure may be a more accurate estimate of the true OS because the calculated survival rate is derived from a larger database which better represents the geographic distribution of the US population.

Our sample’s demographic distributions for HN-AS were consistent with what has been previously reported in the literature [11, 13–16]. There have only been 6 prior studies that included both a sample of at least 45 patients and evaluated prognostic factors for cHN-AS [10–13, 16, 17] (Table 5). Of these studies, only 1 [11] found age > 70 years to be associated with decreased survival. Four studies [10, 12, 13, 16] concluded that advanced age was not significantly associated with a poorer OS. Three of these studies [10, 13, 16] did report lower OS rates in their older cohorts, but univariate testing did not reach the prescribed level of significance. Our study found that older patients had both significantly poorer OS and DSS, and our improved statistical power likely allowed us to detect OS differences that previous authors, limited by smaller samples, were unable.

Table 5.

Univariate independent predictors associated with poorer survival in cutaneous head and neck angiosarcomas among previous studies with > 45 subjects

| Author, year | Sample size, n | 5-year OS, % | Age | Tumor size | Histologic grade | AJCC stage | Surgery | Margin status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holden, 1987 [12] | 72 | 12 | ns | > 10 cm | ns | – | – | – |

| Guadagnolo, 2011 [17] | 70 | 43 | – | > 5 cm | – | – | No surgery | ns |

| Ogawa, 2012 [16] | 48 | 22.1* | ns | ns | – | – | No surgery | – |

| Dettenborn, 2014 [11] | 80 | 62** | > 70 years | ns | ns | – | – | Positive |

| Patel, 2015 [13] | 55 | 38 | ns | ns | ns | – | ns | ns |

| Bernstein, 2017 [10] | 50 | 16 | ns | ns | ns | ns | – | ns |

|

Lee, 2018*** (present study) |

1250 | 17.7 | 70 years | 5 cm | High | Stage 3 or 4 | No surgery | – |

ns not significant

*2-year OS

**Disease-specific survival

***93.5% cutaneous lesions

– Not assessed

In our study, univariate analyses revealed that the tumor factors of size 5 cm, higher histologic grade, increased AJCC stage, and disseminated SEER historic stage were significantly associated with decreased OS and DSS. Only 2 [12, 17] out of the 6 prior studies evaluating cHN-AS prognostic factors also reported significantly poorer OS rates with tumor size 5 cm. The remaining 4 studies [10, 11, 13, 16] did report lower survival with increased size, but as was the case with patient age, statistical testing did not demonstrate significance. Bernstein et al. [10] found that AJCC stage 3/4 disease had a slightly lower OS than stage 2 but their difference did not reach significance. All 4 studies [10–13] comparing histologic grade found no significant OS differences, although Holden et al. [12] noted that well-differentiated tumors appeared to survive longer. We found that histologic grade was not a significant predictor in either of our multivariate models, and this suggests that lower grade lesions might have been more common in younger patients with localized disease.

The traditional mainstay of cHN-AS treatment focuses on wide local excision with adjuvant radiotherapy [5, 19]. Two prior studies [16, 17] showed cHN-AS OS benefits with surgery (versus no surgery) while 1 study [13] reported an improvement that did not reach statistical significance. Our study did not assess surgical margins, however the results of previous studies suggest that negative resection margins may not confer a survival benefit [10, 13, 17]. Some have proposed that, because of the multifocal nature of cutaneous AS growth, true negative margins are extremely difficult to achieve and that surgery should aim to debulk rather than chase negative margins [20]. Our univariate analyses support the current role of surgery with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy to significantly improve both OS and DSS. However, these results should be interpreted with caution because surgery as an independent predictor of survival lost significance in our investigated multivariate models, and therefore those who did not receive surgery may have been older with more advanced disease that was not amendable to resection. Radiation monotherapy has been accepted to be an inferior alternative to surgery [17], and current evidence recommends first-line chemotherapy only for unresectable and metastatic disease [19]. Still, given the poor survival outcomes with mainstay surgical therapy, the role of first-line systemic treatment regiments is an area of active investigation. Phase 2 trials have been conducted on paclitaxel [21] and bevacizumab [22] and there is some evidence suggesting that chemoradiotherapy is superior to conventional surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy [23].

In a recent meta-analysis of scalp and face AS, Shin et al. [18] provide a comprehensive summary of the available literature, much of which we have previously addressed. Their meta-analysis of univariate statistics reported that age 70 years, size 5 cm, scalp location, and lack of surgery were associated with significantly decreased 5-year OS [18]. Shin et al. found that histologic grade was not related to survival. Given that none of the large studies from Table 5 were significant for histologic grade, their result comes as little surprise since their data were pooled from the numbers of past studies. Our population study formally confirms the findings of multiple smaller studies, namely that age, tumor size, and stage are independent predictors of survival. In addition, we are the first large-scale study to suggest that AS patients with lower histologic grade and surgery falsely appear to have improved survival because their presenting lesions may be smaller and more localized.

Although the SEER database provides researchers the opportunity to analyze population data, there are limitations to the dataset that previous authors using similar methods have acknowledged. Over the years, classification schemes and variables of interest have changed, and it was not always possible to retroactively recode the data. This was particularly problematic when determining AJCC 6th edition staging for lesions recorded before 2004, as it was often impossible to retrofit the data. Precise size measurements and extend of disease may be inaccurate because AS may have multifocal satellite or skip lesions. Although some have suggested that histologic features be used to stratify the risk of smaller tumors [24], information regarding specific features, such as pattern of growth, predominant cell type, and the presence of necrosis, were not available. SEER does not differentiate between congenital and sporadic lesions, as original diagnoses were not reviewed histologically for consistency. Radiation treatment variables were recently removed from the public research database, and chemotherapy variables have never been included in the data. With respect to surgical treatment, extent of resection and margin status are unavailable. However, despite these limitations multiple prior studies have successfully used the SEER database to provide useful reports on rare head and neck malignancies.

In conclusion, by utilizing population data we were able to overcome the power limitations of previous studies on HN-AS. Overall, 74.8% of patients died at or before their last follow-up, half of whom died from disease-specific causes. Five-year OS and DSS rates were found to be 26.5 and 48.3% respectively, which were at the lower end of what was previously reported in the literature. The majority of HN-AS were cutaneous, and cHN-AS had a significantly lower DSS. We propose that patients with older age, increased tumor size, and distant disease are at significantly greater risk of overall and disease-specific death at any follow-up timepoint. We found that lower histologic grade and the presence of surgery, when all other predictors are controlled for, do not significantly improve the risk of death. Past reports of improved survival with surgery may be biased toward those cases amenable to resection, and despite mainstay surgical therapy survival rates for HN-AS are poorer than those of reported for other soft tissue sarcomas. Efforts should continue toward developing systemic monotherapies that may eventually supplant surgery as the first-line treatment of choice.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest declared by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Huang J, Mackillop WJ. Increased risk of soft tissue sarcoma after radiotherapy in women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2001;92(1):172–180. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<172::AID-CNCR1306>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma A, Schwartz RA. Stewart-Treves syndrome: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(6):1342–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee FI, Harry DS. Angiosarcoma of the liver in a vinyl-chloride worker. Lancet (London England) 1974;1(7870):1316–1318. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Lao IW, Yu L, Wang J. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors in angiosarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 200 patients from a single Chinese medical institute. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(5):5370–5378. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, Fujimura T, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: the possibility of new treatment options especially for patients with large primary tumor. Front Oncol. 2018;8:46. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez MC, Padhya TA, Messina JL, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a single-institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3391–3397. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouhani P, Fletcher CD, Devesa SS, Toro JR. Cutaneous soft tissue sarcoma incidence patterns in the U.S.: an analysis of 12,114 cases. Cancer. 2008;113(3):616–627. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinnamon AJ, Neuwirth MG, McMillan MT, et al. A prognostic model for resectable soft tissue and cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114(5):557–563. doi: 10.1002/jso.24352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albores-Saavedra J, Schwartz AM, Henson DE, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma. Analysis of 434 cases from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, 1973–2007. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15(2):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein JM, Irish JC, Brown DH, et al. Survival outcomes for cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp versus face. Head Neck. 2017;39(6):1205–1211. doi: 10.1002/hed.24747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dettenborn T, Wermker K, Schulze HJ, Klein M, Schwipper V, Hallermann C. Prognostic features in angiosarcoma of the head and neck: a retrospective monocenter study. J Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surg. 2014;42(8):1623–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holden CA, Spittle MF, Jones EW. Angiosarcoma of the face and scalp, prognosis and treatment. Cancer. 1987;59(5):1046–1057. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870301)59:5<1046::AID-CNCR2820590533>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel SH, Hayden RE, Hinni ML, et al. Angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: the Mayo Clinic experience. JAMA Otolaryngol. 2015;141(4):335–340. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark RJ, Tran LM, Sercarz J, Fu YS, Calcaterra TC, Juillard GF. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck. The UCLA experience 1955 through 1990. Arch Otolaryngol. 1993;119(9):973–978. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880210061009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullins B, Hackman T. Angiosarcoma of the head and neck. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19(3):191–195. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa K, Takahashi K, Asato Y, et al. Treatment and prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: a retrospective analysis of 48 patients. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1019):e1127–e1133. doi: 10.1259/bjr/31655219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK, Araujo D, Ravi V, Shellenberger TD, Sturgis EM. Outcomes after definitive treatment for cutaneous angiosarcoma of the face and scalp. Head Neck. 2011;33(5):661–667. doi: 10.1002/hed.21513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin JY, Roh SG, Lee NH, Yang KM. Predisposing factors for poor prognosis of angiosarcoma of the scalp and face: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 2017;39(2):380–386. doi: 10.1002/hed.24554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishida Y, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: update on biology and latest treatment. Curr Opin Oncol. 2018;30(2):107–112. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buschmann A, Lehnhardt M, Toman N, Preiler P, Salakdeh MS, Muehlberger T. Surgical treatment of angiosarcoma of the scalp: less is more. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61(4):399–403. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31816b31f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penel N, Bui BN, Bay JO, et al. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel for unresectable angiosarcoma: the ANGIOTAX Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(32):5269–5274. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, et al. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(1):257–263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujisawa Y, Yoshino K, Kadono T, Miyagawa T, Nakamura Y, Fujimoto M. Chemoradiotherapy with taxane is superior to conventional surgery and radiotherapy in the management of cutaneous angiosarcoma: a multicentre, retrospective study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1493–1500. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyrup AT, McKenney JK, Tighiouart M, Folpe AL, Weiss SW. Sporadic cutaneous angiosarcomas: a proposal for risk stratification based on 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32(1):72–77. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180f633a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]