Abstract

Stensen’s duct carcinoma (StDC) is an extremely rare neoplasm, with fewer than 40 cases reported in the literature. We report a unique case of primary StDC with papillary features and intestinal differentiation of a 74-year-old male. We discuss the radiologic and pathologic correlation along with the differential diagnosis of this rare entity.

Keywords: Stensen’s duct, Parotid gland, Carcinoma, Intestinal differentiation

Introduction

Primary tumors arising from the excretory duct of the parotid gland (Stensen’s duct) are exceedingly rare. First reported by Goforth JL in 1927, StDC is mostly described in the literature through case reports [1]. The tumor usually presents as a buccal submucosal mass with elderly patients more likely to be affected. The literature describes several histologic types of StDC including squamous, mucoepidermoid and adenocarcinoma [2]. A differential diagnosis includes primary malignancy of the parotid and minor salivary glands and primary tumors of the oral mucosa. Currently there are no defined criteria or specific ancillary studies to aid in the diagnosis; however, the final diagnosis is usually established by the intraductal location of the tumor and exclusion of primary tumors of the minor salivary glands, parotid gland or of the oral mucosa. Metastatic tumors from distant sites should be ruled out as well [3]. With this background, we report a unique case of primary StDC with papillary features and intestinal differentiation.

Case Report

A 74-year-old male presented with a history of painless swelling on the right side of the buccal mucosa over the past 18 months which he attributed to frequent biting. On physical examination, a fairly mobile mass was palpated deep to the buccal mucosa and centered along the course of the salivary duct. The parotid duct opening was not appreciated, and no saliva was expressed upon manipulation. Cervical lymphadenopathy was absent and parotid gland swelling was not noted. The clinical impression at this point was that of a granulomatous process or a primary neoplasm.

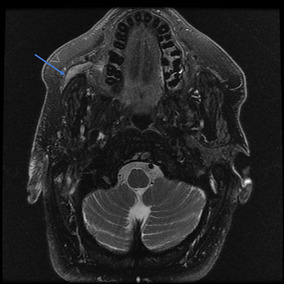

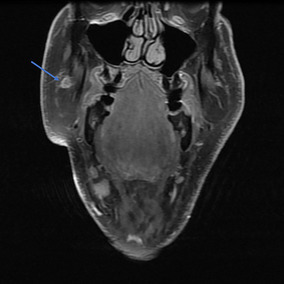

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (Figs. 1, 2) was performed and the T2 weighted images revealed enhancement in the right buccal mucosa at the Stensen’s duct opening. The distal right parotid duct showed abnormal enlargement and thickening, starting at the level of the buccal surface and extending beyond the masseter curvature of the duct. Additionally, the right duct showed diffuse heterogenous enhancement along its course, yet no infiltration of the adjacent fatty tissues was appreciated. In comparison to the left parotid gland, the right side showed atrophy and fatty infiltrate.

Fig. 1.

Axial MRI view of head, T2 fat suppressed image showing tumor dilating and filling the right parotid (Stensen’s) duct (arrow pointing to tumor)

Fig. 2.

Coronal MRI view of head, T1 fat suppressed, post-contrast image again showing tumor dilating and filling the right parotid (Stensen’s) duct (arrow pointing to tumor)

An excisional biopsy demonstrated adenocarcinoma with intestinal features. A transoral excision of the tumor with resection of the parotid duct to the hilum of the parotid gland was subsequently performed. In addition, the entire parotid duct was resected. Grossly the specimen was composed of a 2.2 × 1.1 × 0.8 cm buccal mass, a portion of the parotid gland and a 1.0 cm portion of the parotid duct. The extruded tissue from the duct opening was composed of 0.7 × 0.5 × 0.3 cm tan, red soft tissue fragments. The specimen was serially sectioned to reveal a pink-tan dilated proximal portion of the parotid duct (0.6 cm) and tan-gray mass obliterating the distal portion of the duct (Fig. 3).

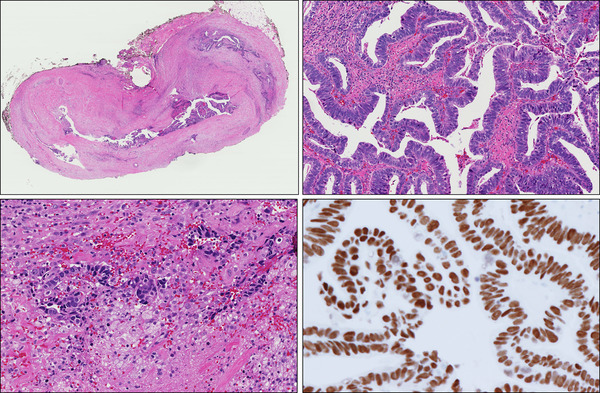

Fig. 3.

Gross specimen photograph of right buccal mass. Black stitch marks the proximal duct margin. Note the distal portion of the duct is obliterated by tan-gray mass. Insert shows a cross section of the mass involving the parotid duct lumen and infiltrating through the duct wall

On microscopic examination; Hematoxylin and Eosin (H & E) sections of Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded tissue (FFPE) demonstrated papillary tumor proliferation with well-developed fibrovascular cores. The papillae were lined by atypical oval to columnar cells with nuclear pseudostratification, high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, coarse chromatin and occasional discernable eosinophilic nucleoli. Most of the cells contained apical secretions. Occasional mitotic figures were identified including atypical forms. The tumor in the main specimen was continuous with the lining of Stensen duct and showed intraductal components with invasion into the ductal wall and the surrounding fibrous tissue. Normal salivary gland tissue was unable to be identified in the background. Immunohistochemical stains showed strong nuclear positivity of the neoplastic cells for CDX-2 which is suggestive of intestinal-type differentiation (Fig. 4). The tumor cells did not show reactivity for androgen receptors.

Fig. 4.

Top left, a photograph of a whole mount section showing a protruding mass involving the dilated duct and extending beyond it to involve the surrounding tissue. Bottom left, tumor invading the ductal wall and the surrounding fibrous tissue. Top right, prominent papillary architecture with intestinal differentiation and strong and diffuse nuclear expression of CDX2 (bottom right)

Discussion

The parotid duct (Stensen’s duct) is the main excretory duct of the parotid gland. Saliva produced in the parotid gland gains access to the oral cavity through Stensen’s duct, which has intra-parotid and extra-parotid segments. Stensen’s duct opens in the vestibule of the mouth next to the second maxillary molar tooth at the parotid ampulla. Tumors of Stensen’s duct are rare and mainly described in the literatures as case reports. These case reports describe the lining epithelial of the tumor giving rise to a variety of carcinomas which can differentiate along different histological lines, including squamous cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma and carcinosarcoma [2]. A tumor can arise anywhere along the duct course; however, the most common location of the tumor is immediately proximal to the duct orifice [3]. From the reported cases, the tumors of the Stensen’s duct appear to have a male predilection with a male to female ratio of 2:1, and wide age of presentation ranging from the 3rd to 8th decades (mean age of 51) [3, 4]. Diagnosis of StDC is established primarily by demonstrating the epicenter of the tumor within the Stensen’s duct and excluding other possible diagnoses.

Our patient presented with painless swelling in the buccal mucosa, mirroring the clinical presentation of reported cases in the literature. Multiple features of this case supported the fact that the origin of the tumor came from Stensen’s duct. The MRI study, as well as the gross examination, revealed that the tumor was located in the distal segment of the parotid duct and extended proximally. Compared to the left parotid gland, the right parotid gland on MRI had shown atrophy and fatty infiltrate. This difference can be explained by chronic obstruction of the right parotid duct. In our case, the duct orifice was obstructed due to the presence of the tumor epicenter within the Stensen’s duct, which was confirmed during the surgery, as tumor fragments were extruded from inside the duct upon manipulation. Moreover, on histologic examination intraductal component was identified.

The possibility of an alternative diagnosis was carefully entertained. In our case, the tumor extended to the ductal orifice, meaning the differential diagnosis had to include tumors of the minor salivary gland; however, Stensen’s duct is usually not obstructed in these neoplasms [5], and no possible other primary tumor was identified in the nearby tissue during surgery. Other possibilities included a primary tumor of the parotid gland. This diagnosis was less likely because the parotid gland was atrophic, no tumor was identified on a clinical exam and no tumor was identified on the submitted portion of the superficial parotid tissue. Our case showed intestinal differentiation. PET scan along with a CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis showed no evidence of other potential primary sites of malignancy. Upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy with corresponding biopsies showed only mild gastritis and a single tubular adenoma within the colon, but failed to reveal any primary GI tract malignancy. Fiberoptic nasal endoscopy exam excluded any skull base tumors that could have explained the patient’s ductal malignancy representing a metastatic lesion from this site.

More importantly, this entity should not be confused with salivary duct carcinoma, which is a high-grade tumor that arises from the excretory duct reserve cells rather than the main parotid/ Stensen’s duct [6]. A salivary duct carcinoma shows histologic and biologic features similar to mammary ductal carcinoma and usually expresses androgen receptors, which was negative in this case [7, 8]. Salivary duct carcinoma has a poor prognosis with local recurrence and high rate of lymph node and distant metastasis. The overall prognosis of the StDC is not well characterized. With so few cases reported, it is not feasible to compare survival rates to the histologic type and treatment modality. It is worth mentioning that a case of primary salivary duct carcinoma arising from the Stensen’s duct has been recently reported [9].

Papillary architecture has been previously described in StDC. In addition, StDC arising from a background of intraductal papilloma has also been described [3, 10, 11]. The papillary configuration observed in the present case, as well as the patient’s presentation with swelling, could raise the possibility that the tumor was arising in a background of intraductal papilloma. Clear cut invasion was observed in our case, supporting the diagnosis of invasive StDC. Also, our case showed an intestinal differentiation which was supported by CDX-2 expression; however, the significance of this is not known.

On follow-up, the patient was last seen 5 months after surgery and showed no signs of disease recurrence. He had a post-resection MRI that showed no evidence of recurrence. Follow up for our patient includes visits every 6 months with repeat MRIs for the foreseeable future, as our ability to monitor this area can be challenging.

In summary, we are reporting a unique case of StDC with papillary architecture and intestinal differentiation. To the best of our knowledge, StDC with intestinal differentiation has not previously reported.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

- 1.Jl G. Carcinoma developing in the parotid (Stensen’s) duct. Am J Med Sci. 1927;173:624–629. doi: 10.1097/00000441-192705000-00004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner M, Gould AR, Miller RL, Johnson JA. Malignant tumors of Stensen’s duct. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:73–77. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(99)70298-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nissanka-Jayasuriya EH, Odell EW, Falconer DT. Stensen’s duct carcinoma with a papillary architecture. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:412–416. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0596-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frechette CN, Demetris AJ, Barnes EL, Futrell JW. Primary carcinoma of Stensen’s duct: recognition and management with literature review. J Surg Oncol. 1984;27:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930270102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batsakis JG. Pathology consultation accessory parotid gland. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988;97:434–435. doi: 10.1177/000348948809700420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murrah VA, Batsakis JG. Salivary duct carcinoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1994;103:244–247. doi: 10.1177/000348949410300315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kleinsasser O, Klein HJ, Hübner G. Salivary duct carcinoma. A group of salivary gland tumors analogous to mammary duct carcinoma. Arch Klin Exp Ohren Nasen Kehlkopfheilkd. 1968;192:100–105. doi: 10.1007/BF00301495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams MD, Roberts D, Blumenschein GR, Temam S, Kies MS, Rosenthal DI, et al. Differential expression of hormonal and growth factor receptors in salivary duct carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1645–1652. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180caa099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noda K, Hirano T, Okamoto T, Suzuki M. Primary salivary duct carcinoma arising from the Stensen duct. Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95:E15–E17. doi: 10.1177/014556131609500907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiotani A, Kawaura M, Tanaka Y, Fukuda H, Kanzaki J. Papillary adenocarcinoma possibly arising from an intraductal papilloma of the parotid gland. ORL. 1994;56:112–115. doi: 10.1159/000276621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagao T, Sugano I, Matsuzaki O, Hara H, Kondo Y, Nagao K. Intraductal papillary tumors of the major salivary glands: case reports of benign and malignant variants. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:291–295. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0291-IPTOTM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]