Abstract

This study addresses the hypothesis that IL-6/STAT3 signaling is of clinical relevance in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC). We evaluated relationships between key components of this pathway in tumors from a unique cohort of n = 59 fully annotated, treatment-naïve patients with OPSCC. The multiplex Opal platform was utilized for immunofluorescence (IF) analysis of tissues to detect IL-6 and phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3), taking into consideration its nuclear versus cytoplasmic localization. Abundant staining for both IL-6 and pSTAT3 was evident in tumor-rich regions of each specimen. IL-6 correlated with cytoplasmic pSTAT3 but not nuclear or total pSTAT3 in this cohort of OPSCC tumors, regardless of p16 status (r = 0.682, p < 0.0001). There was a significant association between increased total pSTAT3, nuclear pSTAT3, cytoplasmic pSTAT3 and IL-6 in p16 negative tumors. Our data indicate STAT3 phosphorylation was a key feature in p16-negative OPSCC tumors. When IL-6 data was stratified by median expression in tumors, there was no association with overall survival. In contrast, both total and nuclear pSTAT3 were significant predictors of poor overall and disease free survival. This strong inverse relationship with overall survival was present in p16 negative tumors for both total and nuclear pSTAT3, but not in p16 positive OPSCC tumors. Together these data indicate that activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway is a marker of p16 negative tumors and relevant to OPSCC prognosis and a potential target for treatment of this more aggressive OPSCC sub-population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12105-018-0962-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Interleukin-6, STAT3, P16, Cytokines, Head and neck cancer, Squamous cell carcinoma

Introduction

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is a malignancy with a high recurrence rate and poor prognosis when it presents at advanced stages [1]. Multimodality treatments (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy) lend further complexity to patients, as these procedures can be disfiguring and contribute to functional deficits, including inability to effectively chew or swallow, and impaired speech [2]. OPSCC is a heterogeneous disease linked to infection by high risk human papilloma virus (HPV) in the majority of cases, but HPV negative OPSCC has worse prognosis than HPV positive disease [3]. Since EGFR targeting is currently an integral part of treating first-line metastatic OPSCC, the understanding of relevant alterations and resistance mechanisms to EGFR targeting such as (i.e. HER2, ErbB3/HER3) is important [4, 5]. These inherent variables affect the outcome of patients with advanced OPSCC and are a topic of research in the treatment of advanced disease [6–8]. Greater insight into key features of this disease are clearly needed to inform its biology and uncover new targets that can complement existing treatment approaches.

More recently, immunotherapy targeting T cell inhibitory and activating receptors have emerged as a therapeutic strategy that can elicit complete and durable responses in OPSCC. The activity of these agents has garnered further interest in immune features in the tumor microenvironment (TME) that may influence the course of disease and the response of tumors to conventional or immune-based therapy. One prominent feature of tumors in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) patients is the dysregulated profile of immunomodulatory cytokines that fuels a network of redundant immunosuppressive cellular and soluble factors in the TME. Collectively, these factors thwart antitumor T cell responses, and may limit the efficacy of immunotherapy. Indeed, altered systemic cytokines are evident in patients with advanced SCCHN, and have been linked to advanced disease [9–13].

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) has emerged as a prominent cytokine in OPSCC, given its distinct tumor-intrinsic and extrinsic roles. This pleiotropic Th2 cytokine binds membrane receptor complexes containing the common signal transducing receptor chain gp130 (glycoprotein 130) [14], thereby initiating a complex series of signaling events that involve the Jak/STAT, NF-κB, MAPK and PI3K pathways [15, 16]. In particular, STAT3 is activated via phosphorylation at Tyr705 in SCC specimens and is of interest as a therapeutic target in this disease [17]. Together, these signaling pathways induced by IL-6 and other cytokines promote a feed-forward loop of soluble factors that act concurrently upon malignant cells and their supporting microenvironment. Signaling downstream of IL-6 is relevant in SCC tumorigenesis and progression via promoting cell growth and catalyzing the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [18, 19]. In addition, IL-6 and other Th2 cytokines can mediate immune suppression, via their ability to alter T cell phenotype, function and facilitate the expansion of multiple suppressive immune cell subsets [17, 20].

Evidence exists that STAT3 is up-regulated and constitutively activated in both primary human head and neck tumors as well as in normal mucosa of HNSCC patients compared to normal mucosa from patients without cancer diagnosis [21]. Furthermore, it has been reported that HPV- HNSCC is characterized by co-activated STAT3 and NF-κB pathways and that this phenotype can be effectively targeted with combined anti-NF-κB and anti-STAT therapies [22]. In the present study, we hypothesized that IL-6/STAT3 signaling is of clinical relevance in OPSCC. We evaluated the relationships between key components of this pathway along with other key biologic features of disease and clinical outcomes data from a unique cohort of fully annotated, treatment-naïve specimens obtained from patients with OPSCC. This study may lend further support to the potential for components of this pathway as a therapeutic target in subsets of SCCHN.

Materials and Methods

Patient Characteristics

This study was conducted using a total of 59 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) specimens from patients with a diagnosis of OPSCC at the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. All specimens were obtained under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol at Emory University and clinical characteristics were obtained in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA). Patient specimens for this study were obtained prior to any treatment for their disease between the years 1994–2008. Key clinical parameters including gender, race, p16/HPV status, smoking status (never, former or current), pathologic data (differentiation, tumor stage, presence of metastasis to lymph nodes) and number of treatments were all considered as variables in this analysis. These clinical data were obtained from clinically-annotated source documents including pathologic reports and other relevant electronic medical records.

Opal Multiplex Immunofluorescence (IF) Analysis

Double fluorescence staining (Opal520 and Opal 620) was obtained using a PerkinElmer Opal kit (Catalog # NEL821001KT, Hopkinton, MA.) Staining was optimized and performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, FFPE tissue sections were heated at 60 °C for 1 h, deparaffinized with series of xylenes, and rehydrated with decreasing concentrations of alcohol followed by formaldehyde fixation. The slides were subjected to antigen retrieval using microwave treatment (MWT) followed by cooling at room temperature. Tissue sections were blocked with blocking agent provided with the kit and incubated for 1 h with primary antibody against IL-6 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX. Clone 1, dilution 1:200) in a humidified chamber. Opal polymer HRP Ms + Rb (Perkin Elmer, Hopkington, MA) was used as the secondary antibody. IL-6 visualization was accomplished using Opal 620 Fluorophore (1:100), after which the slides were placed in target antigen retrieval solution and heated using MWT. The slides were then incubated with pSTAT3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA. Clone D3A7, dilution 1:50) for overnight at 4° followed by secondary antibody. This primary antibody specifically recognizes STAT3 phosphorylated at tyrosine-705. pSTAT3 staining was visualized using Opal 520 Fluorophore (1:100) and the slides were placed in target antigen retrieval solution for MWT to remove unbound antibody. Nuclei were subsequently stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole solution provided along with the kit, and the sections were coverslipped using Prolong Gold mounting media (Thermo Fisher Scientific). In each batch of the IF staining, colon cancer tissues provided by pathology core of Emory University School of Medicine and known to have immune reactivity to pSTAT3 or IL-6 antibody were used as positive controls. IF staining which lacks the relevant primary antibody was used as negative control (Fig. 1).

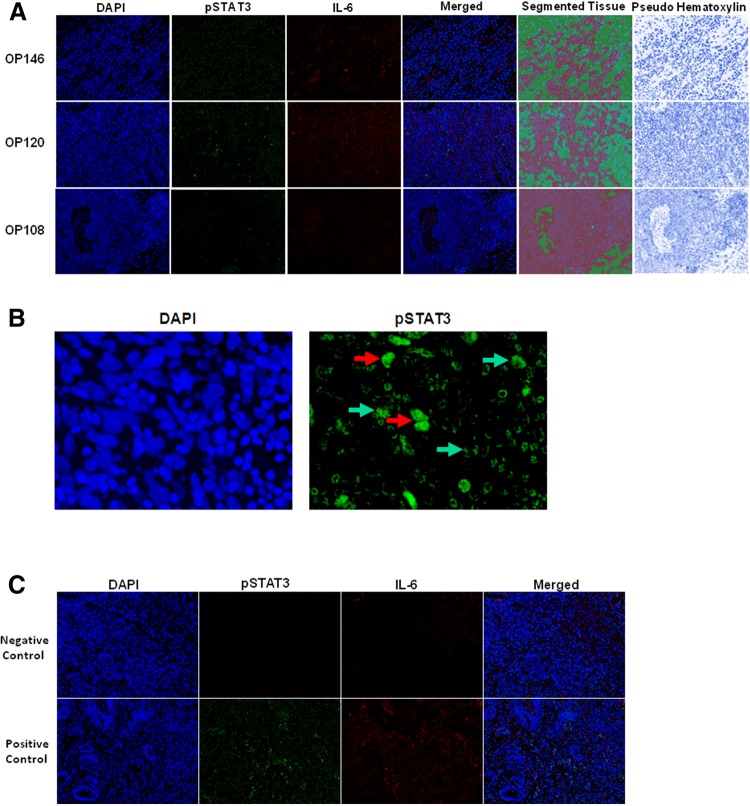

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence staining of IL-6 and pSTAT3 in OPSCC cases. a Three areas were randomly selected while taking pictures at × 200 and were analyzed using inFORM analysis software, which quantifies the segmented tissue based on respective biomarker expression. OPSCC cases OP146 and OP120 are P16 Negative (high expression) and OP108 is P16 positive (low expression). The far panel depicts pseudo hematoxylin stains for each image to illustrate morphology. b Subcellular localization of phosphorylated STAT3 in the nuclear (red arrows) and cytoplasmic (green arrows) compartments of a representative OPSCC case. c Staining from representative negative controls (no primary antibody), or a human colorectal cancer specimen with positivity for IL-6 and pSTAT3 as a positive control

Imaging Analysis with Nuance Imaging System and InForm Software

Three tumor images were captured randomly for each of the samples at × 200 magnification using Nuance imaging system (PerkinElmer), which captures the fluorescent spectra at 20 nm wavelength intervals from 420 to 720 nm with identical exposure times, and combines them to create a single stacked image. Images of single-stained tissues and unstained tissue were used to extract the spectrum of each fluorophore and of tissue autofluorescence, respectively, and to establish a spectral library required for multispectral unmixing before obtaining the images from the samples. Image analysis was performed using InForm image analysis software (PerkinElmer). InForm software analysis allows objective counting of cell populations and biomarker signals and increases accuracy of statistical analysis. Algorithms for the three images randomly selected from the tissues and subcellular compartment separation were created by machine learning function built in InForm software. All algorithms created by machine learning had approximate precision above 90%, and were used for separating tissue morphology into tumor and stroma, and to identify nuclei to accurately assign associations for positive staining to a specific compartment in the tumor microenvironment. All immunostains and subsequent segmented InForm analysis images were examined by a head and neck pathologist (CCG) for accuracy using pseudo-hematoxylin images (Fig. 1a) and referencing with a hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain from the same patient. This strategy was used to enrich the fields of view for tumor-rich regions, although it did not formally exclude all non-malignant cells.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were first used to summarize the characteristics for each patient. To assess the correlations between categorical clinical factors and numerical biomarker variables, t test or ANOVA tests were conducted when data followed a normal distribution, otherwise Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal–Wallis test were used instead. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to measure the correlation between two numerical variables, and the significance of coefficients were tested using Wald’s test. For disease free survival (DFS), disease progression or death from any cause was defined as the event. Time of DFS was calculated as the time from study enrollment to disease progression date, death date, or last contact whichever comes first. For overall survival (OS), death from any cause was defined as the event. Time of OS was calculated as the time from study enrollment to death or last contact. For both DFS and OS, patients were censored at time of last follow-up. OS and DFS rates of two patient groups stratified by each biomarker or other factors were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between different groups using the log-rank test, respectively. The DFS and OS of each patient group at specific time points, such as 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years, etc. were also estimated alone with 95% CI. Cox proportional hazards models were further used in the multivariable analyses to assess adjusted effects of biomarkers on the patients’ OS and DFS after adjusting for other factors. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated graphically and analytically with regression diagnostics. All data management and statistical analysis were conducted using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics

Tumor specimens from a total of n = 59 patients diagnosed with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) were analyzed in this study (Table 1). The median age of this patient cohort was 58 years, consistent with demographics of this disease [3]. The majority of patients enrolled in this study were Caucasian (44.1%) and 78% were male. Never smokers comprised 15.3% of the patients, while 44.1% and 40.7% were former or current smokers, respectively. Most tumors were early stage (T1/2 = 90.7%), moderately or poorly differentiated (MD = 45.8%; PD/NK = 50.8%), with nodal involvement (65.7% ≥ N1). While all tumors were obtained prior to any treatment for OPSCC, most patients included in this cohort received subsequent therapy with radiation (65.5%) or chemoradiotherapy (21.8%). Finally, 64.4% of patient tumors were positive for p16, a surrogate for HPV involvement [3]. These data permitted us to stratify staining data for IL-6 and pSTAT3 based on p16 status, and identify potential associations between disease biology and this key cytokine or its canonical downstream signaling pathway.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical characteristics and biomarkers

| Variable | Level | N (%) | Nuclear pSTAT3 | Cyto pSTAT3 | Total pSTAT3 | Total IL6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | p Value | Mean (SD) | p Value | Mean (SD) | p Value | Mean (SD) | p Value | |||

| Gender | Male | 46 (78.0) | 0.89 (0.42) | 0.064 | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.711 | 0.64 (0.27) | 0.098 | 0.63 (0.08) | 0.347 |

| Female | 13 (22.0) | 1.15 (0.49) | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.79 (0.30) | 0.65 (0.08) | |||||

| Race | AA | 8 (13.6) | 1.43 (0.27) | 0.003 | 0.14 (0.07) | 0.409 | 0.93 (0.16) | 0.017 | 0.64 (0.11) | 0.651 |

| White | 50 (44.1) | 0.87 (0.43) | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.28) | 0.63 (0.08) | |||||

| Unknown | 1 (40.7) | 1.12 (–) | 0.11 (–) | 0.82 (–) | 0.56 (–) | |||||

| Smoking | Never | 9 (15.3) | 0.72 (0.30) | 0.157 | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.543 | 0.55 (0.22) | 0.198 | 0.65 (0.05) | 0.805 |

| Former | 26 (44.1) | 0.93 (0.39) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.66 (0.24) | 0.63 (0.09) | |||||

| Current | 24 (40.7) | 1.05 (0.52) | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.74 (0.74) | 0.63 (0.08) | |||||

| Differentiation | WD | 2 (3.4) | 0.87 (0.20) | 0.07 | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.448 | 0.62 (0.12) | 0.096 | 0.67 (0.02) | 0.497 |

| MD | 27 (45.8) | 1.09 (0.44) | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.76 (0.28) | 0.62 (0.06) | |||||

| NK | 30 (50.8) | 0.82 (0.44) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.60 (0.28) | 0.64 (0.10) | |||||

| Tumor stage | 1 | 24 (44.4) | 0.94 (0.42) | 0.871 | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.086 | 0.68 (0.27) | 0.891 | 0.65 (0.10) | 0.600 |

| 2 | 25 (46.3) | 1.00 (0.50) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.70 (0.70) | 0.63 (0.06) | |||||

| 3 | 3 (5.6) | 0.85 (0.39) | 0.18 (0.10) | 0.62 (0.27) | 0.60 (0.16) | |||||

| 4 | 2 (3.7) | 0.78 (0.33) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.55 (0.21) | 0.59 (0.002) | |||||

| Missing | 5 | |||||||||

| Treatment | Radiother | 36 (65.5) | 0.90 (0.40) | 0.358 | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.218 | 0.65 (0.26) | 0.498 | 0.62 (0.08) | 0.490 |

| Chemo-Rad | 12 (21.8) | 1.10 (0.58) | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.75 (0.36) | 0.65 (0.10) | |||||

| None | 7 (12.7) | 1.05 (0.40) | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.74 (0.26) | 0.64 (0.06) | |||||

| Missing | 4 | |||||||||

| Node metastasis | 0 | 20 (34.5) | 1.15 (0.50) | 0.033 | 0.14 (0.06) | 0.053 | 0.81 (0.31) | 0.027 | 0.65 (0.11) | 0.660 |

| 1 | 7 (12.2) | 0.77 (0.19) | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.58 (0.13) | 0.63 (0.08) | |||||

| 2 | 28 (48.3) | 0.87 (0.40) | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.62 (0.26) | 0.62 (0.06) | |||||

| 3 | 3 (5.2) | 0.55 (0.32) | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.44 (0.24) | 0.65 (0.07) | |||||

| Missing | 1 | |||||||||

| Variable | N | Nuclear pSTAT3 | Cyto pSTAT3 | Total pSTAT3 | Total IL6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson CC | p Value | Pearson CC | p Value | Pearson CC | p Value | Pearson CC | p Value | |||

| Age | 59 | 0.245 | 0.061 | 0.209 | 0.113 | 0.250 | 0.057 | 0.151 | 0.252 | |

Bold values indicate p < 0.05

Multiplex IF Analysis of IL-6, pSTAT3 and Their Association with Clinical Parameters in OPSCC

The multiplex Opal platform was utilized for IF analysis of tissues to detect IL-6 and phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) in the same area of interest (AOI), taking into consideration its nuclear versus cytoplasmic localization. The Opal platform allows simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers using Opal-reactive Fluorophores within the same AOI. This technology permits unmixing of signals between spectral wavelengths and quantification of signals based on their expression in cellular compartments. Multispectral IF staining from a representative tumor section is shown in Fig. 1 and demonstrates abundant staining for both IL-6 and pSTAT3 in tumor-rich regions of each specimen. Primary tumors from patients with nodal metastasis had significantly reduced nuclear pSTAT3 as compared to those without metastasis by univariate analysis (Table 1; p = 0.03). In contrast, no relationship between total pSTAT3 (combined nuclear and cytoplasmic staining), cytoplasmic pSTAT3 or IL6 was observed for any of the variables of interest when considered in univariate analyses. IL-6 correlated with cytoplasmic pSTAT3 but not nuclear or total pSTAT3 in this cohort of OPSCC tumors, regardless of p16 status (r = 0.682, p < 0.0001). Since EGFR and IL-6 can elicit cross talk via the Jak/STAT pathway [23, 24], other canonical receptors of relevance to the EGFR pathway were also measured using standard IHC methodology as reported in our recent publication [8]. EGFR, HER2, and HER3 all displayed prominent expression on tumor cells contained within each specimen.

Activation of the IL-6/STAT3 Signaling Pathway is Restricted Primarily to p16 Negative OPSCC Tumors

Individual covariates of interest were also considered in the context of p16 status for this analysis. There was a significant association between increased total pSTAT3, nuclear pSTAT3, cytoplasmic pSTAT3 and IL-6 in p16 negative tumors (Table 2). These data were further analyzed in the context of expression data from our other receptors of relevance to OPSCC that influence EGFR signaling (EGFR, HER2, HER3) or immune response (PD-1, PD-L1, PD-L2) [8]. Of these covariates only IL-6 was significantly correlated with EGFR expression across all tumors (r = 0.289; p = 0.026) and among p16 negative tumors (r = 0.5347; p = 0.015) (Table S1–3).

Table 2.

Comparison of biomarkers between p16 positive patients and negative patients

| Covariate | Statistics | p16 | Parametric p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (N = 21) | Positive (N = 38) | |||

| Nuclear pSTAT3 | Mean | 1.25 | 0.78 | < 0.001 |

| SE | 0.43 | 0.37 | ||

| Cyto pSTAT3 | Mean | 0.15 | 0.1 | < 0.001 |

| SE | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||

| Total pSTAT3 | Mean | 0.86 | 0.57 | < 0.001 |

| SE | 0.27 | 0.24 | ||

| Total IL6 | Mean | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.009 |

| SE | 0.09 | 0.07 | ||

Expression of pSTAT3 in OPSCC Tumors is Associated with Reduced Overall and Disease-Free Survival

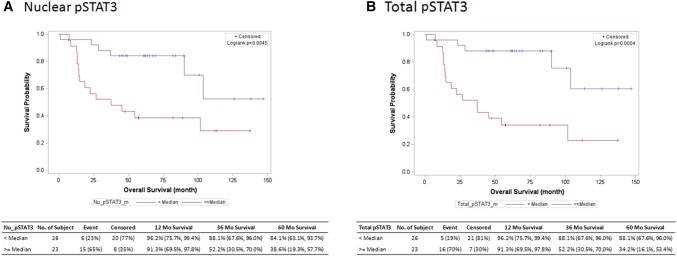

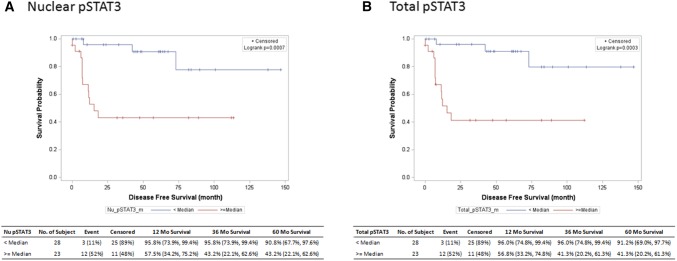

The relationship between IL-6/pSTAT3 components in OPSCC tumors and survival was next evaluated. When IL-6 data was stratified by median expression values in tumors, there was no association with overall survival. In contrast, both total (hazard ratio 0.19, 95% CI 0.07–0.53) and nuclear (hazard ratio 0.28, 95% CI 0.11–0.71) localized pSTAT3 were significant predictors of poor overall survival (Fig. 2a, b), as well as disease free survival (Fig. 3a, b). This strong inverse relationship between pSTAT3 and overall survival was present in p16 negative tumors for both total (hazard ratio 0.11, 95% CI 0.01–0.89, p < 0.001) and nuclear (hazard ratio 0.11, 95% CI 0.01–0.89, p < 0.001) localized pSTAT3, but not in p16 positive OPSCC tumors (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

The relationship between overall survival and a nuclear pSTAT3 and b total STAT3 is depicted in months as a Kaplan–Meier Plot showing product-limit survival estimates

Fig. 3.

The relationship between disease-free survival and a nuclear pSTAT3 and b total STAT3 is depicted in months as a Kaplan–Meier Plot showing product-limit survival estimates

Table 3.

OS and DFS Hazard Ratio of Dichotomized Biomarkers

| Covariate | Level | N | OS in month | DFS in month | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Log-rank p value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Log-rank p value | |||

| Nuclear pSTAT3 | < Median | 26 | 0.28 (0.11–0.71) | 0.004 | 0.15 (0.04–0.53) | < 0.001 |

| > Median | 23 | – | – | – | ||

| Cyto pSTAT3 | < Median | 26 | 0.58 (0.24–1.38) | 0.212 | 0.49 (0.17,1.39) | 0.170 |

| > Median | 23 | – | – | – | ||

| Total pSTAT3 | < Median | 26 | 0.19 (0.07–0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.13 (0.04–0.48) | < 0.001 |

| > Median | 23 | – | – | – | ||

| Total IL6 | < Median | 27 | 0.98 (0.42–2.31) | 0.964 | 1.43 (0.51–4.01) | 0.498 |

| > Median | 22 | – | – | – | ||

Bold values indicate p < 0.05

Discussion

Measuring key cytokines and signaling events can give insight into the biology of tumors, their clinical relevance and provide data to inform novel therapeutic targets. This report addresses the role of IL-6 and activation of STAT3, its canonical downstream transcription factor in tumors from a well-defined cohort of OPSCC patients. Importantly, all tumors were obtained from patients upon their initial diagnosis, thus reflect underlying biology of the tumors, rather than treatment exposure which could influence results. Our data indicate STAT3 phosphorylation is a key feature in p16-negative OPSCC tumors. This observation highlights the need for additional study into relationships between activation of this key oncogenic pathway and the role of HPV in these tumors. The significant relationship between pSTAT3, p16 status and patient survival in this cohort of treatment naïve tumors is certainly novel, and consistent with other published reports. A prior study by Verma et al. also uncovered a relationship between activation of STAT3 and other inflammatory signaling pathways (AP-1 and NF-κB) in p16 negative oral cancer [25]. The present study compliments these results in an additional cohort of patients, and provides further data linking this pathway to both overall and disease free survival. Consistent with the dichotomy in STAT3 phosphorylation and p16 status, we observed a strong relationship between phosphorylated STAT3 and reduced overall and disease free survival. Together these data indicate that activation of the STAT3 signaling pathway is a marker of p16 negative tumors and relevant to OPSCC prognosis and a potential target for treatment of this more aggressive OPSCC sub-population.

In contrast to pSTAT3, intratumoral IL-6 expression was not associated with p16 status or clinical outcomes in this cohort of patients. These results do not support IL-6 as a key predictive marker in untreated OPSCC tumors or an added biomarker to differentiate between tumors with a higher likelihood of HPV-involvement. This likely also reflects the redundancy by which STAT3 phosphorylation can be achieved in the tumor microenvironment [17]. Certainly multiple cytokines or growth factors over-expressed in OPSCC tumors have potential to activate Jak-STAT signal transduction to promote proliferative and metastatic gene expression profiles. These include VEGF, IL-10, and EGF, among others [26]. Furthermore, many tumors including OPSCC and HNSCC often display constitutive STAT3 phosphorylation. In other systems this can occur in response to mutations in genes encoding upstream kinases, such as SRC [27]. Finally, STAT3 activation was less prevalent in specimens from patients with tumor-positive lymph nodes. Though STAT3 signaling was reported to support epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [28, 29], studies in SCCHN remained mostly in cell line models. Our observation on the relationship between lymph node status and activation of STAT3 is the first with a focus on OPSCC tissues. In OPSCC, it is known that HPV positive OPSCC has high frequency of lymph node involvement which may not be induced by STAT3 activation since pSTAT3 level is higher in HPV negative than HPV positive OPSCC. A more comprehensive understanding into the molecular profile of individual OPSCC tumors could certainly be of value in understanding the stimuli responsible for activation of STAT3 in these tumors beyond the presence of IL-6.

Despite the lack of association between IL-6 and clinical parameters, it is worth noting that IL-6 promotes resistance of tumors to systemic cytotoxic and local radiotherapy, and remains important in the context of standard-of-care treatment. For instance, IL-6 levels are increased in SCCHN patient tissues following conventional therapies including radiation [30–34], chemotherapy [9, 35], and targeted therapies [36]. Evidence suggests that IL-6 can mediate resistance to radiation by suppressing oxidative stress via the Nrf2-antioxidant pathway in OPSCC [37]. These data implicate IL-6 as a clinically-relevant mediator of therapeutic resistance in SCC of the oropharynx and head and neck. Certainly, with IL-6 targeting agents being FDA-approved for other indications, the potential to translate data from pre-clinical studies into patients is quite feasible.

Some key strengths of these analyses from our single institution experience include the use of a well-annotated collection of tumor specimens from treatment naïve patients, and use of an innovative, quantitative imaging analysis platform. This has resulted in a robust dataset that produced information for both nuclear and cytoplasmic STAT3. This study also has a number of inherent limitations that are important to note in interpreting the data. First, p16 status was utlized as a surrogate for HPV infection, which although is well-accepted, could influence our conclusions. Second, there was a significant difference in the proportion of African American versus caucasian patients and a greater number of male versus female patients in this study. These factors reflect the cohort of patients who consented to this study, rather than the true demographic distribution of the disease across all patients. This certainly could influence the results and limit conclusions from this study across other patient groups who may be of a different racial profile. Considering these limitations, care should be taken in future validation cohorts to encompass a more balanced demographic distribution of patient tissues so that conclusions can be better generalized. Finally, given the limited quantity of tissue available, the expression of IL-6 and pSTAT3 was measured via a single histologic approach. Since cytokines can be present in the extracellular space, their detection can be problematic. Although this remains an inherent technical limitation, these biomarkers have been detected successfully by our group in tumors from other origins, such as pancreatic cancer [38], and the expression of IL-6 and cytoplasmic pSTAT3 were indeed correlated in specimens from this study.

In conclusion, these data provide new insight into the role of IL-6 and pSTAT3 expression in OPSCC tumors and their relationship to key phenotypic and clinical outcomes. The results justify additional investigation into the role of STAT3 or its upstream cytokines as key factors that influence the biology of p16 negative tumors, and potentially a viable target for therapeutic intervention.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/NCI under Award Numbers P30CA138292 and 1R01CA208253-01 (G. Lesinski).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Contributor Information

Dong M. Shin, Email: dmshin@emory.edu

Nabil F. Saba, Phone: (404)-778-1900, Email: nfsaba@emory.edu

References

- 1.Pignon JP, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke P, et al. Speech and swallow rehabilitation in head and neck cancer: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(S2):S176–S180. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang KK, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian G, et al. Heregulin and HER3 are prognostic biomarkers in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3600–3611. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, et al. HER3 targeting sensitizes HNSCC to cetuximab by reducing HER3 activity and HER2/HER3 dimerization: evidence from cell line and patient-derived xenograft models. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(3):677–686. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fayette J, et al. Randomized phase II study of duligotuzumab (MEHD7945A) vs. cetuximab in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MEHGAN Study) Front Oncol. 2016;6:232. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saba NF. Commentary: randomized phase II study of duligotuzumab (MEHD7945A) vs. cetuximab in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MEHGAN Study) Front Oncol. 2017;7:31. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steuer CE, et al. A correlative analysis of PD-L1, PD-1, PD-L2, EGFR, HER2, and HER3 expression in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(3):710–716. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao J, Zhao S, Halstensen TS. Increased interleukin-6 expression is associated with poor prognosis and acquired cisplatin resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(6):3265–3274. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leon X, et al. Expression of IL-1alpha correlates with distant metastasis in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(35):37398–37409. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guenin S, et al. Interleukin-32 expression is associated with a poorer prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2014;53(8):667–673. doi: 10.1002/mc.21996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green VL, et al. Serum IL10, IL12 and circulating CD4+ CD25 high T regulatory cells in relation to long-term clinical outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Int J Oncol. 2012;40(3):833–839. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hathaway B, et al. Multiplexed analysis of serum cytokines as biomarkers in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck patients. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(3):522–527. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000157850.16649.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose-John S, et al. Interleukin-6 biology is coordinated by membrane-bound and soluble receptors: role in inflammation and cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80(2):227–236. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher DT, Appenheimer MM, Evans SS. The two faces of IL-6 in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(1):38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheller J, et al. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813(5):878–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DE, O’Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(4):234–248. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dominguez C, David JM, Palena C. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and inflammation at the site of the primary tumor. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;47:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiesel BF, et al. Toxicity, pharmacokinetics and metabolism of a novel inhibitor of IL-6-induced STAT3 activation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;78(6):1225–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3181-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grandis JR, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling abrogates apoptosis in squamous cell carcinogenesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(8):4227–4232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaykalova DA, et al. NF-kappaB and stat3 transcription factor signatures differentiate HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(8):1879–1889. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colomiere M, et al. Cross talk of signals between EGFR and IL-6R through JAK2/STAT3 mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition in ovarian carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(1):134–144. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Squarize CH, et al. Molecular cross-talk between the NFkappaB and STAT3 signaling pathways in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2006;8(9):733–746. doi: 10.1593/neo.06274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verma G, et al. Characterization of key transcription factors as molecular signatures of HPV-positive and HPV-negative oral cancers. Cancer Med. 2017;6(3):591–604. doi: 10.1002/cam4.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(11):798–809. doi: 10.1038/nrc2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, et al. Activation of Stat3 in v-Src-transformed fibroblasts requires cooperation of Jak1 kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(32):24935–24944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bharti R, Dey G, Mandal M. Cancer development, chemoresistance, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and stem cells: a snapshot of IL-6 mediated involvement. Cancer Lett. 2016;375(1):51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wendt MK, et al. STAT3 and epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in carcinomas. JAKSTAT. 2014;3(1):e28975. doi: 10.4161/jkst.28975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russo N, et al. Cytokines in saliva increase in head and neck cancer patients after treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122(4):483–90 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zang C, et al. IL-6/STAT3/TWIST inhibition reverses ionizing radiation-induced EMT and radioresistance in esophageal squamous carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(7):11228–11238. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yadav A, et al. Bazedoxifene enhances the anti-tumor effects of cisplatin and radiation treatment by blocking IL-6 signaling in head and neck cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(40):66912–66924. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centurione L, Aiello FB. DNA Repair and Cytokines: TGF-beta, IL-6, and Thrombopoietin as Different Biomarkers of Radioresistance. Front Oncol. 2016;6:175. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, et al. IL-6 signaling promotes DNA repair and prevents apoptosis in CD133+ stem-like cells of lung cancer after radiation. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:227. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0534-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Tamatani T, et al. Enhanced radiosensitization and chemosensitization in NF-kappaB-suppressed human oral cancer cells via the inhibition of gamma-irradiation- and 5-FU-induced production of IL-6 and IL-8. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(6):912–921. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanam A, et al. Upregulated interleukin-6 expression contributes to erlotinib resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 2015;9(7):1371–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuoka Y, et al. IL-6 controls resistance to radiation by suppressing oxidative stress via the Nrf2-antioxidant pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(10):1234–1244. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mace TA, et al. IL-6 and PD-L1 antibody blockade combination therapy reduces tumour progression in murine models of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2018;67(2):320–332. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.