Abstract

Cervicofacial actinomycosis is a common form of Actinomyces infection. However, the latter seldom occurs in the tongue. We present a case of a 66 year-old man with macroglossia caused by actinomycosis of the tongue. Radiographic features were compatible with a chronic inflammatory disease. Biopsies revealed granulomas containing giant cells and Gram positive bacterial clusters consistent with actinomycosis. The patient was treated with a 22 week course of antibiotics. Imaging showed a notable improvement in the extent of the lesions 1 year later. The patient was asymptomatic and in good condition during his second year follow-up. Diagnosis of actinomycosis of the tongue can prove to be challenging because of the non-specific nature of its symptoms, clinical signs, and radiographic features. Isolation of Actinomyces sp. is an added diagnostic hurdle, because of its fastidious nature.

Keywords: Actinomycosis, Actinomyces, Tongue, Macroglossia

Introduction

Orofacial actinomycosis is a relatively common infection. Its clinical appearance is remarkably varied, and may present as periodontal infections, pericoronitis, non-healing extraction sites, ulcerations, and so on. Actinomycosis is known to mimic numerous conditions, including malignancies [1–3]. Furthermore, secondary actinomycosis often complicate preexisting conditions, such as osteoradionecrosis and osteonecrosis of the jaws related to bone-targeted therapy [4, 5].

Actinomycosis of the tongue is a very rare occurrence and represents less than 3% of cases of cervicofacial actinomycosis [6, 7]. It has been reported as a tongue mass [6, 8], as an enlargement of the tongue [9, 10], and as a unilateral swelling of the tongue [7].

True macroglossia is a relatively rare condition that may be caused by a wide variety of local and systemic conditions. Local conditions include muscular hypertrophy, hamartomas and neoplasia, the most frequent of which are lymphangioma, hemangioma, and squamous cell carcinoma [10–12]. Systemic causes include hypothyroidism, gigantism, acromegaly, angioedema, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis and other types of granulomatous disease [10, 12–14].

Case Report

A 66 year-old Caucasian male was initially seen by an otolaryngologist with a 1 year history of progressive macroglossia and loss of lingual motricity. According to the patient, his dentist had noted that his denture had become unstable. At the time of his initial visit, the patient complained of dysphagia and speech impediment. He denied having pain, dysesthesia or dyspnea. The relevant medical history included steatosis, renal cysts, a 45 pack-years tobacco intake and a daily alcohol consumption of up to five drinks. Patient also denied any history of oral or cervicofacial trauma.

Physical examination revealed generalized enlargement of the tongue extending to the base of tongue without any surface ulceration (Fig. 1). There was no induration or palpable mass; however, restriction of tongue movements was evident. Cranial nerves were unaffected and the head and neck examination was otherwise within normal limits.

Fig. 1.

Clinical oral examination shows a diffuse enlargement of the tongue. No surface ulceration was detected. The photo has been taken after the first biopsy

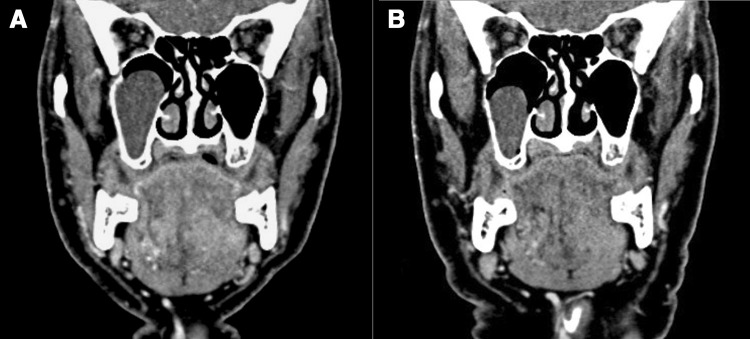

A contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed and revealed diffuse, bilateral soft-tissues opacities of the tongue that extended into the mylohyoid and genioglossus muscles (Fig. 2a). A polyp in the right maxillary sinus was incidentally detected. Cervical lymph nodes were not involved. Radiographic features were suggestive of chronic inflammatory disease.

Fig. 2.

Coronal section of a craniofacial computed tomography scan with contrast showing diffuse bilateral radiopacities in the tongue (a), and slight improvement 1 year later (b). A retention cyst/polyp in the right maxillary sinus was also noted as an incidental finding, and subsided without any treatment

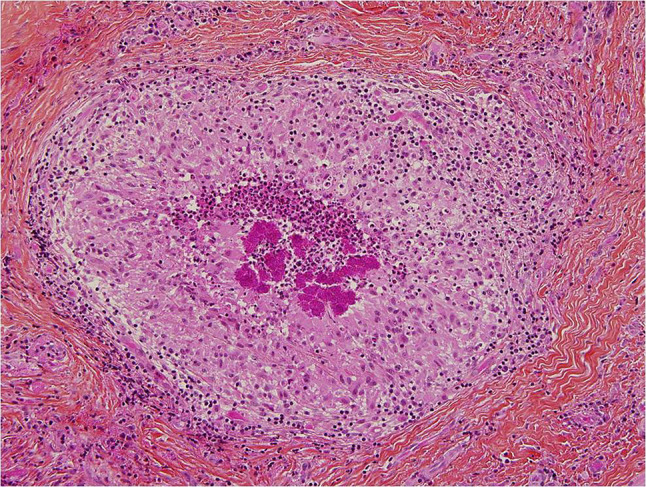

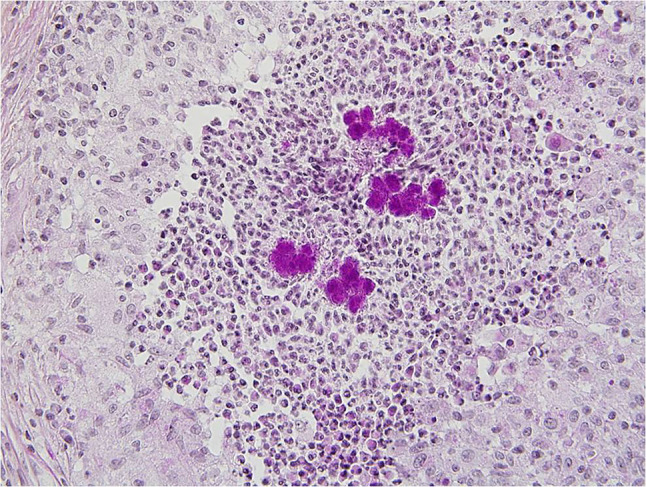

Cultures were negative for Mycobacteria and Actinomyces. Three incisional biopsies were performed at different times. Histology of all three specimens revealed the presence of numerous granulomas with central abscess formation (Fig. 3) Giant cells were present in most granulomas. Many granulomas contained eosinophilic, Gram positive, PAS-D (periodic acid-Schiff-diastase) positive bacterial clusters, consistent with Actinomyces infection (Fig. 4). Grocott, Giemsa and acid-fast bacilli stains were negative. Features of neoplasia were absent.

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin–eosin stained section revealing the presence of granulomas. Magnification level 10 × 10

Fig. 4.

Section stained with periodic acid-Schiff with diastase showing the presence of eosinophilic clusters in the granulomas, consistent with actinomycosis. Magnification level 10 × 10

Before completing the diagnostic work-up, the patient was empirically treated with piperacillin/tazobactam (3.375 g every 6 h) for 2 weeks. When the diagnosis of actinomycosis was confirmed, the antimicrobial therapy was changed to intravenous penicillin G (3.5 × 106 U every 4 h) for 8 weeks followed by oral penicillin V (300 mg every 6 h) for 12 weeks. 1 year later, a second CT scan revealed slight improvement in the extent of the lesions (Fig. 2b). However, residual scar-like opacities were still present, without any evidence of necrosis. The patient was asymptomatic and free of disease 2 years after the initial diagnosis, and was lost to follow-up afterwards.

Discussion

Actinomyces species consists of a heterogeneous group of Gram positive, anaerobic, non-spore-forming, pleomorphic rods, and are part of the normal oral flora [15, 16]. Actinomyces israelii is the most common pathogen isolated in cervicofacial actinomycosis [17, 18]. In the latter, Actinomyces species are often isolated in combination with other aerobic and/or anaerobic bacteria [18]. Actinomyces is thought to infect deep tissues via a point of entry, such as mucosal lesions, endodontic pathways and periodontal pockets [17, 19]. Dental caries, invasive dental or maxillofacial procedures, trauma and radionecrosis are the most common causes [19, 20]. No racial or geographic predisposition has been reported [21]. The main predisposing factors include diabetes, alcohol abuse, malnutrition and immunosuppression [20]. Furthermore, patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) often had poor outcomes [22, 23].

Actinomycosis is usually a chronic, progressively enlarging, fluctuant mass characterized by abscess formation, woody fibrosis and can also be associated with draining sinus tracts and sulfur granules [22, 24, 25]. The latter are characteristic of actinomycosis. In a study by Weese and Smith, they were present in about 54% of 57 cases [26]. However, the presence of sulfur granules is not pathognomonic, as they can also be present in nocardiosis. Actinomycosis of soft tissues may extend to adjacent bone in up to 15% of cases [1, 19]. Lymphadenopathy is uncommon but can develop later [17, 20].

Although actinomycosis can affect any structure of the cervicofacial area, it involves the mandibular area (submandibular region, ramus and angle) in over 50% of cases [20, 27].

Early diagnosis of actinomycosis can be difficult for many reasons. First, patients may delay seeking medical attention because symptoms are non-specific, and can be either absent or mild at first. Actinomycosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of any long-standing cervicofacial pathologic condition [17, 24, 27–29]. Belmont et al. [17] state that fewer than 10% of infections are accurately diagnosed on initial presentation because they are often confused with pyogenic abscesses or neoplasia. Blood tests are usually unhelpful; however, leukocytosis may be present in some cases [26]. Radiographic features are non-specific and may resemble any chronic inflammatory process [17, 20, 24]. Secondly, cultivating Actinomyces sp. is notoriously difficult, thus leading to a high percentage of false negative.

A culture may yield a positive result in less than 30% of cases and may take up to 3 weeks [24, 25]. Some authors recommend an incisional biopsy as a mean to determine a definitive diagnosis [17]. Others advocate fine needle aspiration (FNA) as the method of choice of diagnosing cervical actinomycosis. Less invasive, this diagnostic technique is accurate, safe and simple. It allows morphologic identification and collection of material needed for microbiologic cultures [17, 20]. We feel that this method, although simple and minimally invasive, may yield false negative results, especially if antibiotic therapy has been empirically initiated. We believe that in the context of actinomycosis diagnosis, the biopsy should remain the gold standard.

Cervicofacial actinomycosis may respond to several antibiotics, such as penicillin, tetracycline, clindamycin, erythromycin, third-generation cephalosporins and many others. Penicillin is the drug of choice, but there seems to be no agreement on the ideal duration of therapy. Some studies have shown that a 3–10 weeks antibiotic therapy, combined or not with surgery, may be sufficient, while some authors advocate long term treatment (6–12 months). Tetracycline and erythromycin can replace penicillin in allergic patients, and cephalosporins can be used in co-infection not responding to penicillin [17, 20, 28–31]. The use of steroids may be helpful in treating any residual inflammatory granulomatous reaction [21], however, we believe further studies are needed to assess the validity of this treatment. Surgery is indicated whenever bone is involved, or in presence of necrotic tissue, and in the presence of a sinus tract [22, 30, 32]. Whenever clinically feasible, pharmaceutical treatment should be preferred to surgical excision [17, 22].

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Miller M, Haddad AJ. Cervicofacial actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:496–508. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raj AT, Patil S. Cervicofacial actinomycosis can obscure a malignancy: a case report. Oral Oncol. 2018;80:94. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozkan A, Topkara A, Ozcan RH. Facial actinomycosis mimicking a cutaneous tumor. Wounds. 2017;29:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koerdt S, Dax S, Grimaldi H, et al. Histomorphologic characteristics of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:448–453. doi: 10.1111/jop.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan I, Anavi K, Anavi Y, et al. The clinical spectrum of Actinomyces-associated lesions of the oral mucosa and jawbones: correlations with histomorphometric analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atespare A, Keskin G, Ercin C, et al. Actinomycosis of the tongue: a diagnostic dilemma. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:681–683. doi: 10.1017/S0022215106001757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brignall ID, Gilhooly M. Actinomycosis of the tongue. A diagnostic dilemma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;27:249–253. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(89)90153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuepper RC, Harrigan WF. Actinomycosis of the tongue: report of case. J Oral Surg. 1979;37:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhler IV, Dolan LA. Actinomycosis of the tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1972;34:199–200. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(72)90408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizer FM, Schechter GL, Richardson MA. Macroglossia: etiologic considerations and management techniques. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1985;8:225–236. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(85)80083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guelmann M, Katz J. Macroglossia combined with lymphangioma: a case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2003;27:167–169. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.27.2.a466020r10440121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Topouzelis N, Iliopoulos C, Kolokitha OE. Macroglossia. Int Dent J. 2011;61:63–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawoud BES, Ariyaratnam S. Amyloidosis presenting as macroglossia and restricted tongue movement. Dent Update. 2016;43:641–642. doi: 10.12968/denu.2016.43.7.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovach TA, Kang DR, Triplett RG. Massive macroglossia secondary to angioedema: a review and presentation of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:905–917. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brailsford SR, Lynch E, Beighton D. The isolation of Actinomyces naeslundii from sound root surfaces and root carious lesions. Caries Res. 1998;32:100–106. doi: 10.1159/000016438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarridge JE, 3rd, Zhang Q. Genotypic diversity of clinical Actinomyces species: phenotype, source, and disease correlation among genospecies. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3442–3448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3442-3448.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belmont MJ, Behar PM, Wax MK. Atypical presentations of actinomycosis. Head Neck. 1999;21:264–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199905)21:3<264::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pulverer G, Schutt-Gerowitt H, Schaal KP. Human cervicofacial actinomycoses: microbiological data for 1997 cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:490–497. doi: 10.1086/376621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reichenbach J, Lopatin U, Mahlaoui N, et al. Actinomyces in chronic granulomatous disease: an emerging and unanticipated pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1703–1710. doi: 10.1086/647945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lancella A, Abbate G, Foscolo AM, et al. Two unusual presentations of cervicofacial actinomycosis and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008;28:89–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bubbico L, Caratozzolo M, Nardi F, et al. Actinomycosis of submandibular gland: an unusual presentation. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004;24:37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sudhakar SS, Ross JJ. Short-term treatment of actinomycosis: two cases and a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:444–447. doi: 10.1086/381099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaudhry SI, Greenspan JS. Actinomycosis in HIV infection: a review of a rare complication. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11:349–355. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JK, Lee HK, Ha HK, et al. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: CT and MR imaging findings in seven patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:331–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volante M, Contucci AM, Fantoni M, et al. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: still a difficult differential diagnosis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2005;25:116–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weese WC, Smith IM. A study of 57 cases of actinomycosis over a 36-year period. A diagnostic ‘failure’ with good prognosis after treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:1562–1568. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1975.00330120040006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerbino G, Bernardi M, Secco F, et al. Diagnosis of actinomycosis by fine-needle aspiration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:381–382. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valour F, Senechal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183–197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brook I. Actinomycosis: diagnosis and management. South Med J. 2008;101:1019–1023. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181864c1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barabas J, Suba Z, Szabo G, et al. False diagnosis caused by Warthin tumor of the parotid gland combined with actinomycosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2003;14:46–50. doi: 10.1097/00001665-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moghimi M, Salentijn E, Debets-Ossenkop Y, et al. Treatment of cervicofacial actinomycosis: a report of 19 cases and review of literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:e627–e632. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oostman O, Smego RA. Cervicofacial actinomycosis: diagnosis and management. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7:170–174. doi: 10.1007/s11908-005-0030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]