Abstract

Women are more susceptible to developing cocaine dependence than men, but paradoxically, are more responsive to treatment. The potent estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), mediates these effects by augmenting cocaine seeking but also promoting extinction of cocaine seeking through E2’s memory-enhancing functions. Although we have previously shown that E2 facilitates extinction, the neuroanatomical locus of action and underlying mechanisms are unknown. Here we demonstrate that E2 infused directly into the infralimbic-medial prefrontal cortex (IL-mPFC), a region critical for extinction consolidation, enhances extinction of cocaine seeking in ovariectomized (OVX) female rats. Using patch-clamp electrophysiology, we show that E2 may facilitate extinction by potentiating intrinsic excitability of IL-mPFC neurons. Because the mnemonic effects of E2 are known to be regulated by brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its receptor, tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB), we examined whether BDNF/TrkB signaling was necessary for E2-induced enhancement of excitability and extinction. We found that E2-mediated increases in excitability of IL-mPFC neurons were abolished by Trk receptor blockade. Moreover, blockade of TrkB signaling impaired E2-facilitated extinction of cocaine seeking in OVX female rats. Thus, E2 enhances IL-mPFC neuronal excitability in a TrkB-dependent manner to support extinction of cocaine seeking. Our findings suggest that pharmacological enhancement of E2 or BDNF/TrkB signaling during extinction-based therapies would improve therapeutic outcome in cocaine-addicted women.

Keywords: cocaine abuse, conditioned place preference (CPP), estrogens, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, electrophysiology, intrinsic excitability, extinction learning, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)

Introduction

Susceptibility to developing cocaine abuse disorders is higher in females than in males, an effect mediated by the actions of estrogens (McCance-Katz et al., 1999; Elman et al., 2001; Lynch et al., 2002; O’Brien and Anthony, 2005; Lejuez et al., 2007; Becker and Hu, 2008; Evans and Foltin, 2010). Previous work has shown that the potent form of estrogen, 17β-estradiol (E2), promotes formation and expression of drug-related memories in females (Lynch et al., 2001; Larson et al., 2007; Evans and Foltin, 2010; Bobzean et al., 2014; Segarra et al., 2014; Doncheck et al., 2018) and enhances learning and memory across multiple behavioral paradigms (Daniel, 2006; Frick, 2012, 2015). Paradoxically, the mnemonic effects of E2 facilitate extinction of cocaine seeking in female rats and lack of E2 in ovariectomized (OVX) female rats results in extinction failure leading to perseverative cocaine seeking across more than 40 days (Twining et al., 2013). Systemic administration of E2, however, rescues extinction learning in these rats (Twining et al., 2013). Extinction memories to suppress fear- and drug-associated behaviors are consolidated in the infralimbic-medial prefrontal cortex (IL-mPFC; Quirk et al., 2000; Peters et al., 2008; Quirk and Mueller, 2008; Torregrossa and Taylor, 2013), but the effects of E2 in this region on neuronal function and extinction learning are unknown. Previous work has demonstrated that E2 alters dorsal hippocampus (DH) function, enhancing neuronal excitability during the proestrus (high E2) phase relative to the metestrus (low E2) phase of the rat estrous cycle (Scharfman et al., 2003). Whether E2 acts within IL-mPFC to promote extinction learning and alter IL-mPFC neuronal excitability remains to be determined.

E2 may promote learning-related plasticity and intrinsic excitability by targeting neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and its high-affinity receptor, tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB; Singh et al., 1995; Aguirre and Baudry, 2009; Hill, 2012; Wu et al., 2013; Fortress et al., 2014; McCarthny et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2019). For example, a single subcutaneous injection or direct infusions of E2 into the hippocampus increase BDNF protein levels in this region (Gibbs, 1999; Fortress et al., 2014). Furthermore, bath-application of a Trk receptor antagonist, K-252a, to hippocampal slices attenuates neuronal excitability during the proestrus (high E2) phase of the rat estrous cycle (Scharfman et al., 2003), suggesting that E2 may enhance neuronal excitability via a BDNF/Trk-dependent mechanism. Whether the interaction between E2 and BDNF/Trk signaling is necessary for IL-mPFC neuronal excitability and whether this interaction supports extinction learning remains unknown.

Using a cocaine conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm, we determined if infusions of E2 in IL-mPFC would facilitate extinction of cocaine seeking in OVX female rats. To assess the physiological effects of E2, we used patch-clamp electrophysiology to investigate if bath-application of E2 would enhance intrinsic excitability of IL-mPFC neurons and whether E2-mediated excitability could be prevented in the presence of Trk receptor antagonists. Additionally, we tested whether E2-BDNF interactions were necessary for extinction of a cocaine CPP in OVX female rats. Our results reveal that E2 enhances excitability in IL-mPFC neurons via BDNF/Trk signaling to promote extinction of a cocaine CPP.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Surgery

Female Long-Evans rats weighing between 275 and 300 g were individually housed in clear plastic cages. Rats were maintained on a 14-h light/10-h dark cycle and had unlimited access to water and standard laboratory chow (Teklad, Harlan Laboratories). Rats were weighed and handled daily for approximately 3 days prior to surgery and before the start of experiments. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines.

Surgeries were performed as previously described (Frick et al., 2004; Otis et al., 2013; Twining et al., 2013). Rats were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine/xylazine (90/10.5 mg/kg, i.p.) and underwent bilateral OVX using a dorsal approach (Frick et al., 2004). A single, horizontal incision was made along the spine and the ovary was isolated. The tip of the uterus was clamped and ligated and the ovary was removed with a scalpel. The remaining tissue was returned to the abdomen. The same procedure was repeated on the other ovary, and the incision was closed with sterile sutures and wound clips. For infusion experiments, rats were implanted with a double-barrel guide cannula aimed bilaterally at IL-mPFC (anteriorposterior, +2.8; mediolateral ±0.6, and dorsoventral, −4.4 mm relative to bregma). Following surgeries, rats were given an antibiotic (penicillin G procaine, 75,000 units in 0.25 mL) and an analgesic (carprofen, 5.0 mg in 0.1 mL) subcutaneously and then allowed to recover for approximately 10 days before behavioral testing.

Drugs

Cocaine HCl (National Institute on Drug Abuse) was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline at a concentration of 10 mg/mL, and administered systemically at a dose of 10 mg/kg, i.p. To ensure that E2 levels did not build over time from repeated infusions, a water-soluble form of E2 dissolved in 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HBC) that is metabolized within 24 h was used (Pitha and Pitha, 1985). HBC vehicle and HBC-encapsulated E2 were dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline (0.2 mg/mL) and injected i.p. at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg (Gresack and Frick, 2006) or directly infused into IL-mPFC at 5 μg/0.5 μl/side (Fernandez et al., 2008). ANA-12 (selective TrkB receptor antagonist) was dissolved in 1% DMSO in physiological saline (Zhang et al., 2015) and administered i.p. at 0.5 mg/kg (Cazorla et al., 2011). For electrophysiological recordings, 25 nM β-estradiol (not HBC encapsulated) was dissolved in 100% DMSO and diluted with artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) to a final DMSO concentration of 0.0001%. K-252a (Trk receptor antagonist) was dissolved in 100% DMSO and bath-applied at 100 nM and diluted with aCSF to a final concentration of 0.001% DMSO (Montalbano et al., 2013).

Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology

Female rats aged 3 months were OVXed and allowed to recover for 7 days. Rats received systemic injections of E2 or HBC vehicle for 3 days before being euthanized for patch-clamp recordings. They were anesthetized with isofluorane, and their brains were rapidly removed and transferred to ice-cold, oxygenated (95%/O2/5% CO2) aCSF containing the following composition (in mM): 124 NaCL, 2.8 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, and 20 dextrose. Coronal slices were cut 400 μM in ice-cold aCSF using a vibrating blade microtome (Leica VT1200). Slices recovered in warm aCSF (32–35°C) for 30 min followed by incubation in room-temperature aCSF for the remainder of the experiment. Slices were transferred to a submersion chamber, mounted, and perfused with aCSF (~2 ml/min; room temperature). Pyramidal neurons with visible apical dendrites in layer 5 of the IL-mPFC were visualized with differential interference contrast using a 60× water-immersion lens on an upright Eclipse FN1 microscope (Nikon Instruments). Whole-cell patch recordings of IL-mPFC pyramidal neurons were obtained using fire polished borosilicate glass pipettes (3–8 MΩ), filled with internal solution containing the following (in mM): 110 K-gluconate, 20 KCL, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 2 ATP, 0.3 GTP, 10 phosphocreatine; 0.2% biocytin, pH 7.3, and 290 mOsm. Intrinsic excitability was obtained with current clamp using a MultiClamp 700B (Molecular Devices) patch-clamp amplifier connected to a Digidata 1440A digitizer (Molecular Devices). The liquid-liquid junction potential (measured as 13 mV) was compensated for all recordings. All electrophysiological data were analyzed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices).

After 10 min of stable recordings, layer 5 IL-mPFC neurons were polarized to approximately −60 mV to control for variance in resting membrane potential. A series of 1 s current steps were applied (−40 to 500 pA; 10 pA steps) and the number of evoked action potentials (APs) was recorded to measure basic membrane properties (Table 1). To measure input resistance, current pulses were injected and the resulting voltage deflections were measured to create a V-I plot. Furthermore, a rheobase was measured, which is the minimum amount of current required to elicit a single AP. Rheobase was analyzed in a subset of layer 5 pyramidal neurons by applying 1 s current steps with 10 pA increments until a single AP was elicited. Intrinsic excitability was measured by applying a 2 s depolarizing step every 7.5 s and evoked APs were recorded. The level of depolarizing step was adjusted to rheobase and remained constant throughout the experiment (Otis et al., 2013). To measure effects of E2 on intrinsic excitability, 25 nM of E2 was bath-applied and baseline current steps were applied every 5 min for approximately 30 min. To ensure that excitability was enhanced by E2 and not by the current pulses on its own, the same protocols were repeated for the same amount of time in slices that remained in aCSF and did not receive any E2 treatment. To measure the effects of K-252a on E2-induced excitability, slices were bathed in 100 nM K-252a (Montalbano et al., 2013) for approximately 20 min before bath-application of E2. Following recording, brain slices were fixed in phosphate-buffered formalin overnight.

Table 1.

Effects of E2 on intrinsic excitability of infralimbic-medial prefrontal cortex (IL-mPFC) pyramidal neurons.

| Group | Time | RN (MΩ) | VRest (MΩ) | Rheobase (pA) | Threshold (mV) | Amplitude (mV) | Half width (ms) | sAHP (ms) | mAHP (ms) | fAHP (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic HBC | Pre E2 | 272.3 ± 33.3 | −58.9 ± 0.5 | 29.0 ± 3.8 | −35.8 ± 0.6 | 73.5 ± 3.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 19.0 ± 1.1 |

| Post E2 | 308.0 ± 39.5* | −58.5 ± 0.7 | 18.0 ± 3.2* | −38.3 ± 0.8** | 71.5 ± 3.5 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 16.1 ± 1.1* | |

| Systemic HBC | Pre E2 + K-252a | 291.7 ± 42.2 | −59.7 ± 0.5 | 35.7 ± 4.8 | −34.0 ± 0.6 | 67.8 ± 3.3 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 22.7 ± 1.1 |

| Post E2 + K-252a | 329.7 ± 41.5* | −60.7 ± 0.4 | 37.1 ± 5.7 | −35.4 ± 0.5 | 64.3 ± 3.5 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 22.9 ± 0.8 | |

| Systemic E2 | Pre E2 | 282.3 ± 35.3 | −59.9 ± 0.6 | 33.3 ± 5.8 | −35.3 ± 1.0 | 72.5 ± 2.6 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 19.6 ± 1.5 |

| Post E2 | 318.0 ± 45.1* | −58.5 ± 0.5 | 26.7 ± 6.0* | −37.2 ± 1.1** | 71.4 ± 2.7 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 17.6 ± 1.4 |

E2, 17β-estradiol; RN, input resistance; Vrest, resting potential; sAHP, slow afterhyperpolarization; mAHP, medium afterhyperpolarization; fAHP, fast afterhyperpolarization. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001.

To confirm that patch-clamp recordings were from layer 5 IL-mPFC neurons, biocytin-filled pyramidal neurons were washed in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 1% NaBH4 in PBS and 10% normal goat serum. The slices were incubated overnight with 3% NGS, 0.2% Triton-X, and PBS. After 24 h, slices were washed in PBS and incubated for 2 h with a green fluorescent antibody (streptavidin, 1:250). Slices were washed with PBS before being mounted with antifade mounting medium and coverslipped and were visualized using 20× magnification with green fluorescent light, to locate neurons and verify that they were pyramidal.

Electrophysiological data were analyzed using Clampfit (Molecular Devices). Basic neuron properties were examined: input resistance, resting membrane potential, AP half-width, AP amplitude, and AP threshold (Table 1). To analyze slow afterhyperpolarization (sAHP), voltage was recorded 1 s following current offset, which was then subtracted from baseline voltage before current injection (Kaczorowski et al., 2012). To analyze medium AHP (mAHP), voltage was recorded 150 ms following current offset, which was then subtracted from baseline voltage before current injection (Song et al., 2015). Fast AHP (fAHP) was measured as the antipeak amplitude relative to AP threshold (Song and Moyer, 2017), which was then subtracted from baseline. Basic measures of intrinsic excitability were analyzed using independent samples t-test before and immediately following drug application. To analyze number of APs, the average number of spikes was plotted against time. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare excitability across time and between groups.

Conditioned Place Preference

Testing and conditioning were conducted in a 3-chamber apparatus in which two larger conditioning chambers (33 × 23 × 29 cm) were separated by a smaller chamber (15 × 18 × 29 cm). The larger conditioning chambers had wire mesh flooring with white walls, whereas the other had gold-grated flooring with a black wall. The center chamber had aluminum sheeting as flooring. All floors were raised 4 cm, with removable trays placed beneath. Removable partitions were used to isolate the rats within specific chambers during conditioning. During baseline and CPP trials, the doors were removed to allow free access to the entire apparatus. Each of the larger chambers contain two infrared photobeams separated by 8 cm. If the beam furthest from the door was broken, then the rat was considered to be in the larger chamber. If only the beam closest to the center chamber was broken, then the rat was considered to be in the center chamber. During all phases of the experiments, the room was kept in semi-darkness.

A pre-test determined baseline preferences by placing the rats into the center chamber with free access to the entire apparatus for 15 min and recording time in each chamber. Rats spent an equal amount of time in the larger conditioning chambers, but less time in the center chamber. ANOVA revealed an effect of chamber for all rats during baseline test (F(2,204) = 98.73, p < 0.001), and post hoc analyses confirmed that less time was spent in the center chamber than either of the conditioning chambers (p < 0.001). Therefore, an unbiased procedure was used, in which rats were randomly assigned to receive cocaine in one of the two larger chambers, independent of baseline preference scores. After a pre-test, rats were conditioned to associate one chamber, but not another, with cocaine in a counterbalanced fashion over 8 days. Systemic cocaine injections were given immediately before placing the rats in their chambers for 20 min conditioning sessions. Following conditioning, rats went through extinction training in which they were placed into the center chamber and allowed free access to the entire apparatus for 15 min.

All rats received daily 0.2 mg/kg, i.p. (Gresack and Frick, 2006) injections of E2 throughout the conditioning phase. Rats received E2 treatment 1 h before eight conditioning trials. Conditioning trials consisted of four pairings with cocaine and four pairings with saline. Following conditioning, rats remained in their homecages for 2 days. To test whether infusions of E2 in IL-mPFC facilitated extinction, HBC vehicle and HBC-encapsulated E2 (0.5 μg/0.5 μl/side; Fernandez et al., 2008) were directly infused in IL-mPFC 5 min prior to each extinction trial. We examined whether inactivation of TrkB receptors impairs extinction by systemically administering the selective TrkB receptor antagonist, ANA-12. One hour prior to each extinction trial (15 min), rats received either systemic injections of 0.2 mg/kg, i.p. E2 (Gresack and Frick, 2006) and 0.5 mg/kg, i.p. ANA-12 (Cazorla et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2015) or E2 and vehicle. ANA-12 was systemically administered 1 h prior to a CPP trial because active concentrations have been detected as early as 30 min and up to 6 h after systemic injections (Cazorla et al., 2011).

After behavioral testing, rats were euthanized with an overdose of ketamine and perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. Brains were removed and placed in 30% sucrose/formalin solution. Following brain submersion, 40 μM thick coronal sections were sliced using a microtome from brain regions in which cannula were implanted. Sections were then mounted and stained with cresyl violet. Injector tip locations were confirmed using a rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007).

Drug-seeking behavior was analyzed using a three-way ANOVA to compare time within each chamber across trials and between groups (Twining et al., 2013; Otis et al., 2014). When appropriate main interaction effects were detected, Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests were used to make pairwise comparisons.

Results

Infusions of E2 in IL-mPFC Facilitate Extinction of Cocaine Seeking

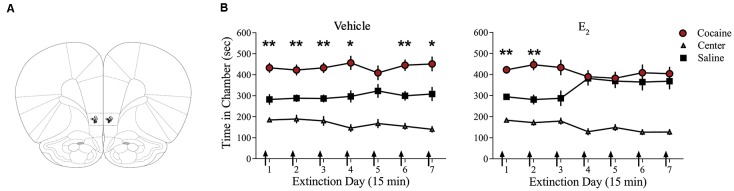

Systemic injections of E2 promote extinction of cocaine seeking in OVX female rats (Twining et al., 2013), but the site of action of E2 is unknown. Consolidation of extinction of cocaine seeking is dependent on actions within the IL-mPFC (Otis et al., 2014; Hafenbreidel et al., 2015), therefore, we tested whether localized infusions of E2 in this region would facilitate extinction in OVX female rats. Following conditioning, rats received IL-mPFC microinfusions of E2 (n = 21; 5 μg/0.5 μl/side) or HBC vehicle (n = 21) 5 min before extinction (Figure 1). ANOVA revealed no significant trial by chamber by group interaction (F(12,480) = 1.004, p > 0.05). However, there was a significant effect of trial by chamber (F(12,480) = 2.554, p < 0.01) and an overall effect of chamber (F(2,80) = 64.152, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis confirmed that both E2-treated and HBC vehicle-treated rats spent more time in the previously cocaine-paired chamber than in the saline-paired chamber during the first trial (p < 0.01). Whereas HBC vehicle-treated rats demonstrated a significant preference for the cocaine-paired chamber during trials 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 7 (post hoc p < 0.05), E2-treated rats did not show a significant preference for the cocaine-paired chamber after trial 2 (post hoc p > 0.05). The results suggest that E2 acts within IL-mPFC to enhance extinction of a cocaine CPP.

Figure 1.

Infusions of E2 into infralimbic-medial prefrontal cortex (IL-mPFC) enhance extinction of a cocaine conditioned place preference (CPP). (A) Coronal drawings showing injector tip placements for IL-mPFC infusions. (B) IL-mPFC infusions (arrows) of E2 (n = 21) but not vehicle (n = 21) before each CPP trial promoted extinction of a CPP. **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. Error bars indicate SEM.

E2 Potentiates IL-mPFC Pyramidal Neuron Excitability

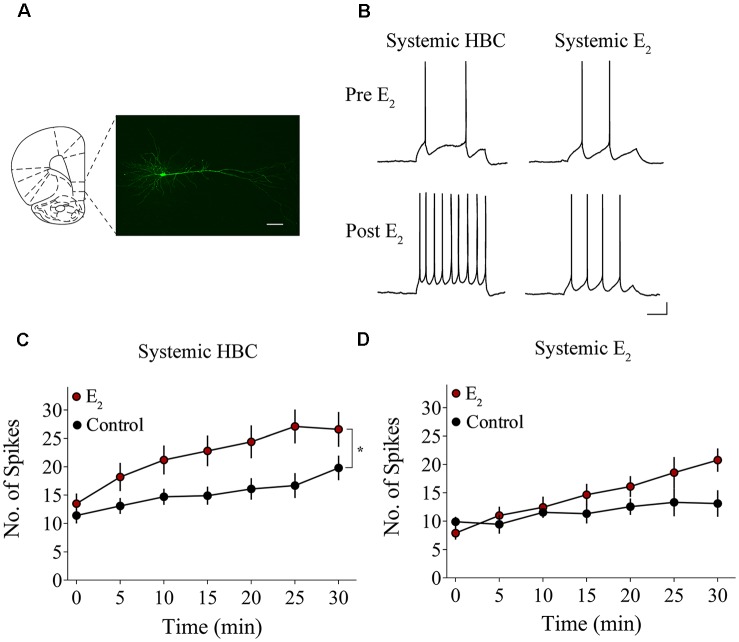

We tested whether bath-application of E2 alters intrinsic excitability in identified layer 5 IL-mPFC pyramidal neurons (Figure 2A). To control for hormonal manipulations prior to recordings, OVX female rats were systemically injected with E2 or HBC vehicle for 3 days before they were euthanized for patch-clamp recordings. Slices extracted from OVX female rats that were previously injected with HBC vehicle were incubated in 25 nM E2 or aCSF and the number of evoked APs were recorded from IL-mPFC neurons (Figures 2B,C). To ensure that excitability was drug-dependent and not due to the current injections, cells in the control group (n = 10) received the same number of current injections over time as cells in the E2 group (n = 10; Figure 2C). Bath-application of E2 (25 nM) increased the number of evoked APs in IL-mPFC neurons (Figure 2C). ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time (F(6,108) = 28.404, p < 0.001) and a treatment by time interaction (F(6,108) = 3.599, p < 0.05). Post hoc tests confirmed that bath-application of E2 significantly increased the number of APs compared to controls (p < 0.05). E2 did not cause membrane depolarization or reduce sAHP (a 1–2 s hyperpolarization that follows a train of APs) but significantly reduced fAHP (a 2–5 ms hyperpolarization that follows a single AP, carried by the calcium- and voltage-dependent BK channel; Storm, 1987) of IL-mPFC neurons (Table 1). Thus, bath-application of E2 enhances excitability of IL-mPFC pyramidal neurons from OVX female rats previously treated with HBC vehicle.

Figure 2.

Bath-application of E2 potentiates IL-mPFC pyramidal neuron excitability. (A) Photomicrograph of a biocytin-filled IL-mPFC pyramidal neuron. Scale bar, 50 μm. (B) Individual traces of current-evoked action potentials (APs) from IL-mPFC pyramidal neurons before (top) and after (bottom) bath-application of E2 in slices from ovariectomized (OVX) female rats that were systemically injected with 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HBC)-vehicle (left) or with E2 (right). Scale bars, 10 mV (vertical) and 500 ms (horizontal). (C) Compared to artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) alone (n = 10), bath-application of E2 (n = 10) enhances intrinsic excitability in IL-mPFC neurons from OVX female rats that were systemically injected with HBC-vehicle prior to recordings. (D) Compared to aCSF alone (n = 9), bath-application of E2 (n = 9) does not enhance intrinsic excitability in IL-mPFC neurons from OVX female rats that were systemically injected with E2 prior to recordings. *p < 0.05. Error bars indicate SEM.

Slices extracted from OVX female rats that were previously treated with E2 were incubated in 25 nM E2 or aCSF and the number of evoked APs were recorded from layer 5 IL-mPFC neurons (Figures 2B,D). The control group (n = 9) received the same number of current injections over time as the E2 group (n = 9; Figure 2D). Interestingly, bath-application of E2 (25 nM) did not increase the number of evoked APs in slices extracted from rats that had previously received systemic injections of E2 (Figure 2D). ANOVA revealed a significant effect of time (F(6,96) = 10.332, p < 0.001), but no significant treatment by time interaction (F(6,96) = 2.933, p > 0.05). In slices from OVX female rats that received systemic injections of E2, bath-application of E2 did not enhance excitability of IL-mPFC neurons.

Trk Receptor Blockade Prevents E2-Induced Potentiation of IL-mPFC Pyramidal Neuron Excitability

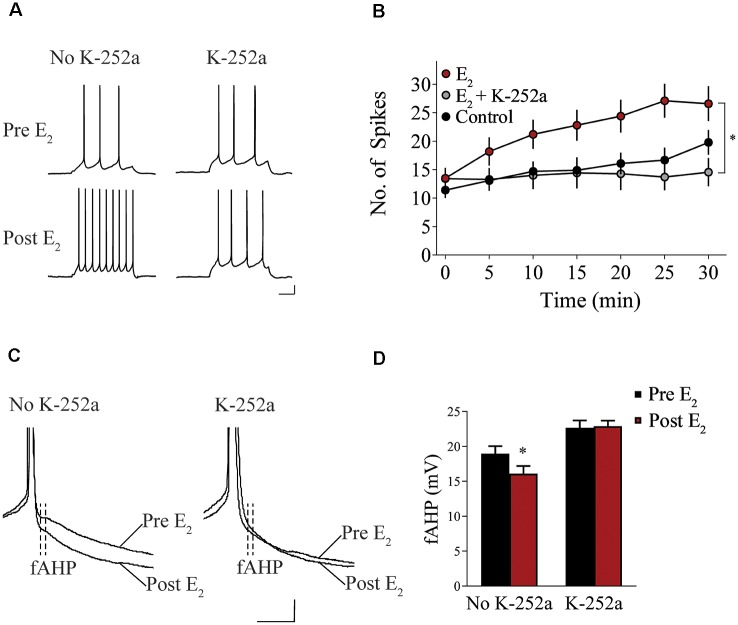

We assessed whether Trk receptor blockade prevents E2-induced enhancement of intrinsic excitability in layer 5 IL-mPFC pyramidal neurons from OVX female rats without prior systemic E2 injections. Slices were first incubated for 20 min in 100 nM K-252a (Montalbano et al., 2013) and then E2 (25 nM) was bath-applied. The effect of E2 was blocked by bath-application of K-252a (Figures 3A,B), indicating that Trk receptor blockade prevents E2-induced potentiation of IL-mPFC neuronal excitability. E2 reduced fAHP and these changes did not occur when slices are incubated with K-252a (Figures 3C,D). Comparing neurons treated with E2 (n = 10), E2 + K-252a (n = 7), and aCSF alone (n = 10), ANOVA revealed an effect of time (F(6,144) = 20.91, p < 0.001), and a treatment by time interaction (F(12,144) = 5.546, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests confirmed that E2 significantly increased the number of APs compared to control or E2 + K-252a administration (p < 0.05). Together, these results show that E2 potentiates excitability in layer 5 IL-mPFC neurons via a Trk receptor-dependent mechanism.

Figure 3.

Blockade of tropomyosin-related kinase (Trk) receptors prevents E2-induced potentiation of IL-mPFC neuronal intrinsic excitability. (A) Individual traces of current-evoked APs from IL-mPFC neurons that were not incubated in K-252a (left) or were incubated in K-252a (right), before (top) and after (bottom) bath-application of E2. Scale bars, 10 mV (vertical) and 500 ms (horizontal). (B) IL-mPFC neurons treated with E2 (n = 10) have increased intrinsic excitability compared to aCSF alone (n = 10) or neurons that were incubated in K-252a prior to bath-application of E2 (n = 7). (C) Representative waveforms showing fast afterhyperpolarization (fAHP) in neurons that were not incubated in K-252a (left) or were incubated in K-252a (right), and after bath-application of E2. Scale bars, 10 mV (vertical) and 10 ms (horizontal). (D) E2 suppresses fAHP and this effect was blocked in the presence of Trk receptor antagonist, K-252a. *p < 0.05. Error bars indicate SEM.

E2-Induced Facilitation of Extinction Is disrupted by TrkB Receptor Blockade

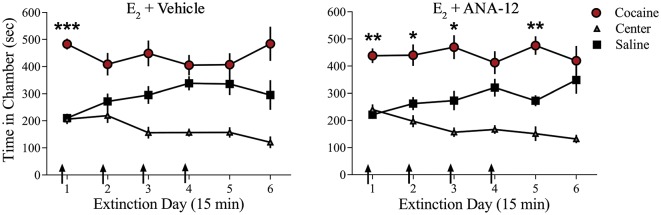

We examined whether TrkB receptor blockade prevented E2-facilitated extinction. Because K-252a does not cross the blood-brain barrier, we used a highly selective TrkB receptor antagonist, ANA-12, that is known to cross the blood-brain barrier effectively (Cazorla et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2015). All rats received 0.2 mg/kg of E2 (Gresack and Frick, 2006) 1 h prior to each CPP test trial. In addition to E2 injections, rats received either a systemic injection of 0.5 mg/kg of ANA-12 (n = 9; Cazorla et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2015) or vehicle (n = 10) 1 h before a CPP trial (Figure 4). ANOVA revealed no significant trial by chamber by group interaction (F(10,170) = 0.1203, p > 0.05). However, there was a significant effect of trial by chamber (F(10,170) = 3.926, p < 0.001) and an overall effect of chamber (F(2,34) = 38.457, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis confirmed that both E2 + ANA-12-treated and E2 + vehicle-treated rats spent more time in the previously cocaine-paired chamber than in the saline-paired chamber during the first trial (p < 0.001). However, E2 + vehicle-treated rats did not show a significant preference for the cocaine-paired chamber during subsequent trials (post hoc p > 0.05). In contrast, E2 + ANA-12-treated rats showed a significant preference for the cocaine-paired chamber during trials 2, 3, and 5 (post hoc p < 0.05). Therefore, E2-induced facilitation of extinction is impaired by TrkB receptor blockade.

Figure 4.

Injections of selective TrkB receptor antagonist disrupted E2-induced facilitation of extinction of a cocaine CPP. Systemic injections (arrows) of E2 + ANA-12 (n = 9) but not E2 + vehicle (n = 10) before the first four CPP trials impaired extinction. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05. Error bars indicate SEM.

Discussion

Systemic E2 administration facilitates extinction of cocaine seeking (Twining et al., 2013), but the locus and mechanism of action have been elusive. Here we show that E2 acts locally within IL-mPFC to faciliate extinction of a cocaine CPP through a BDNF/TrkB-dependent mechanism. First, we found that OVX female rats fail to extinguish in the absence of E2 and that direct bilateral infusions of E2 into IL-mPFC permit extinction of cocaine seeking. Second, we show that E2 acts by enhancing intrinsic excitability in layer 5 IL-mPFC pyramidal neurons from OVX female rats, an effect that is blocked in the presence of a Trk inhibitor. Third, we demonstrate that E2-induced extinction of cocaine seeking is impaired by concurrent blockade of TrkB signaling. Thus, E2 interacts with BDNF/TrkB signaling in IL-mPFC to enhance neuronal excitability and facilitate extinction of cocaine seeking in female rats.

Our findings are consistent with evidence that E2 is necessary for extinction of both conditioned fear (Milad et al., 2010; Zeidan et al., 2011; Graham and Milad, 2013; Graham and Scott, 2018) and cocaine seeking (Twining et al., 2013). Extinction training results in the formation of a new inhibitory memory that masks the original fear or drug memory. Therefore, E2 could promote extinction of fear or cocaine seeking by enhancing acquisition, retrieval, and/or consolidation of the new extinction memory (Torregrossa and Taylor, 2013), the latter of which is mediated by IL-mPFC (Quirk et al., 2000; Quirk and Mueller, 2008). Previous studies demonstrated that women using hormonal contraceptives, which reduce circulating E2 (Rivera et al., 1999), exhibited poorer extinction recall compared to naturally cycling women (Graham and Milad, 2013). Extinction impairment was also observed in female rats treated with hormonal contraceptives, however, these impairments were restored either by exogenous treatment of E2 or by terminating use of hormonal contraceptive after fear conditioning (Graham and Milad, 2013). Similarly, systemic administration of E2 to OVX female rats promoted extinction of cocaine seeking as compared to vehicle-treated rats (Twining et al., 2013). In that study, E2-treated rats extinguished within a week whereas vehicle-treated rats continued to perseverate for over 6 weeks. Importantly, the extinction impairment observed in vehicle-treated OVX rats was reversed by administration of E2 (Twining et al., 2013). We now show that E2 acts locally within IL-mPFC to facilitate extinction of cocaine seeking in OVX female rats. Whether these findings extend to extinction of drug seeking across drug classes, or to extinction of natural reward seeking, remains to be tested.

In addition to showing that E2 acts within the IL-mPFC to facilitate extinction learning, our results are the first to reveal that E2 enhances intrinsic excitability in IL-mPFC neurons. Greater intrinsic excitability lowers the threshold for synaptic changes and is a neural correlate of extinction learning (Daoudal and Debanne, 2003; Santini et al., 2008; Mozzachiodi and Byrne, 2010; Sehgal et al., 2013). We found that bath-application of E2 increased excitability in IL-mPFC neurons from OVX female rats that did not receive systemic E2 injections prior to recordings. Previously, bath-application of E2 was shown to increase excitability in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Wong and Moss, 1991; Kumar and Foster, 2002; Carrer et al., 2003; Woolley, 2007; Wu et al., 2011). E2 enhances excitability by regulating the slow Ca2+-activated K+ current (sIAHP) and suppressing sAHP in hippocampal slices from OVX female rats (Kumar and Foster, 2002; Carrer et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2011). In IL-mPFC neurons, however, E2 did not alter sAHP but reduced fAHP. One reason for this may be that sAHP and fAHP are differentially modulated depending on the type of learning. For example, changes in sAHP occur following fear conditioning (Santini et al., 2008), eye-blink conditioning (Moyer et al., 1996; Thompson et al., 1996), and Morris water maze learning (Oh et al., 2003), whereas fAHP (but not sAHP) is reduced after extinction learning (Santini et al., 2008). Thus, both extinction and E2 may enhance excitability of IL-mPFC neurons through suppression of fAHP.

Bath-application of E2 did not induce excitability or reduce fAHP in IL-mPFC neurons from OVX female rats that received systemic injections of E2 prior to recordings. These results have also been observed in hippocampal neurons where pretreatment of E2 prevented the effects of bath-applied E2 on excitability (Carrer et al., 2003). The lack of excitability changes may be due to a negative feedback mechanism as E2 has been shown to facilitate seizures (Newmark and Penry, 1980; Woolley, 2000). Systemic injections of E2 could have downregulated ERs in IL-mPFC and reduced the effects of E2 bath-application to prevent the induction of seizures. Future work is needed to elucidate exactly how pretreatment with E2 influences the extinction circuitry.

Our findings show that E2 potentiates IL-mPFC neuronal excitability via Trk receptor activation. Behaviorally, E2 may aid extinction of cocaine seeking by regulating BDNF/Trk signaling. BDNF is a likely target as it has been shown to promote extinction of cocaine seeking and fear learning (Peters et al., 2010; Otis et al., 2014), whereas the TrkB receptor antagonist, ANA-12, impaired extinction of cocaine seeking in male rats (Otis et al., 2014). Similarly, we demonstrate that ANA-12 prevents the facilitating effects of E2 on extinction of a cocaine CPP in OVX female rats. Our data support previous work that E2-BDNF interactions may be necessary for learning-related plasticity. For example, E2 replacement in young adult OVX female rats enhances BDNF protein levels in the olfactory bulbs (Jezierski and Sohrabji, 2000, 2001), hippocampus (Gibbs, 1998; Allen and McCarson, 2005; Fortress et al., 2014), cortex (Sohrabji et al., 1995; Allen and McCarson, 2005) amygdala (Liu et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2005), septum (Gibbs, 1999; Liu et al., 2001), dorsolateral area of the bed nucleus terminalis, and the lateral habenular nucleus (Gibbs, 1999). E2 has also shown to increase BDNF expression in the entorhinal cortex of aged OVX female rats (Bimonte-Nelson et al., 2004) as well as in the hippocampus of gonadectomized male mice (Solum and Handa, 2002). Moreover, BDNF is necessary for E2 regulation of dendritic spines and ultimately synaptic transmission. E2-mediated increases in dendritic spine density are attenuated by inhibiting TrkB receptors with K-252a in hippocampal slice cultures (Sato et al., 2007). Furthermore, aromatase knockout mice, which have depleted neuron-derived E2, had a large decrease in both BDNF protein as well as dendritic spine density and these deficits were rescued by treatment with estradiol benzoate (Sasahara et al., 2007; Lu et al., 2019). Although E2 influences multiple brain structures to enhance cognitive processes, evidence to date indicates that E2 primarily targets IL-mPFC to promote extinction of fear- and drug-associated memories. For example, intrahippocampal infusions of E2 did not facilitate extinction of a cocaine CPP in OVX female rats (preliminary data, not shown). Moreover, systemic administration of E2 to naturally cycling rats enhanced c-fos activity in IL-mPFC relative to prelimbic mPFC and central amygdala during fear extinction recall (Maeng et al., 2017). Thus, E2 and BDNF may act synergistically to potentiate plasticity within the IL-mPFC and strengthen extinction learning.

E2 is known to modulate BDNF through regulation of the gene encoding BDNF as this gene contains a sequence similar to the estrogen response element (ERE; Sohrabji et al., 1995). Through the classical genomic mechanism, estrogens bind to intracellular ERs to form complexes, which bind to ERE in the DNA to influence gene transcription. ER-ligand complexes bind to the ERE-like motif on the BDNF gene and may regulate BDNF expression (Sohrabji et al., 1995). Moreover, both E2 and BDNF share common signal transduction pathways and transcription factors. These include signaling through the extracellular regulated protein kinase (ERK; Toran-Allerand et al., 1999; Yamada and Nabeshima, 2003; Boulware et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2019) the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K; Mizuno et al., 2003; Znamensky et al., 2003; Fortress et al., 2013), Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII; Sawai et al., 2002; Blanquet et al., 2003) and cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB; Ernfors and Bramham, 2003; McEwen et al., 2001; Boulware et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2019). Although there are indirect findings that E2 and BDNF interact to enhance memory, much more work is required to understand how E2 activates specific signaling pathways to regulate BDNF/Trk expression.

In conclusion, our data provide the first evidence that E2 localized within IL-mPFC facilitates extinction in female rats through a BDNF/TrkB-dependent mechanism. These findings have implications for the treatment of cocaine abuse in women. Cocaine dependence has increased among adolescent women between the ages of 12–17, and more women are admitted for cocaine abuse treatment compared to their male counterparts (Lejuez et al., 2007). So far, little progress has been made towards sex-specific therapeutic approaches for cocaine addiction. Treatment options, such as extinction-based exposure therapy, have had limited success without any pharmacological adjuncts (Conklin and Tiffany, 2002). Thus, pharmacological enhancement of E2 or BDNF/TrkB signaling may prove to be clinically relevant for the treatment of disorders in women involving maladaptive memories and behavioral inflexibility such as addiction or posttraumatic stress disorder.

Data Availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines.

Author Contributions

HY, KF and DM designed experiments. HY and DM analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. HY, CS, MH, JT, AF and DM carried out the experiments.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to James M. Otis, PhD, Carolynn Rafa Todd and Megha Sehgal, PhD for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 DA038042 to DM, and a grant (00044) from the Puerto Rico Science, Technology and Research Trust to DM.

References

- Aguirre C. C., Baudry M. (2009). Progesterone reverses 17β-estradiol-mediated neuroprotection and BDNF induction in cultured hippocampal slices. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 447–454. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06591.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen A. L., McCarson K. E. (2005). Estrogen increases nociception-evoked brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene expression in the female rat. Neuroendocrinology 81, 193–199. 10.1159/000087002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J. B., Hu M. (2008). Sex differences in drug abuse. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 29, 36–47. 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bimonte-Nelson H. A., Nelson M. E., Granholm A. C. E. (2004). Progesterone counteracts estrogen-induced increases in neurotrophins in the aged female rat brain. Neuroreport 15, 2659–2663. 10.1097/00001756-200412030-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanquet P. R., Mariani J., Derer P. (2003). A calcium/calmodulin kinase pathway connects brain-derived neurotrophic factor to the cyclic AMP-responsive transcription factor in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 118, 477–490. 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00963-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobzean S. A., Dennis T. S., Perrotti L. I. (2014). Acute estradiol treatment affects the expression of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in ovariectomized female rats. Brain Res. Bull. 103, 49–53. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware M. I., Heisler J. D., Frick K. M. (2013). The memory-enhancing effects of hippocampal estrogen receptor activation involve metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling. J. Neurosci. 33, 15184–15194. 10.1523/jneurosci.1716-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware M. I., Weick J. P., Becklund B. R., Kuo S. P., Groth R. D., Mermelstein P. G. (2005). Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on cAMP response element-binding protein. J. Neurosci. 25, 5066–5078. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrer H. F., Araque A., Buño W. (2003). Estradiol regulates the slow Ca2+-activated K+ current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 23, 6338–6344. 10.1523/jneurosci.23-15-06338.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla M., Prémont J., Mann A., Girard N., Kellendonk C., Rognan D. (2011). Identification of a low-molecular weight TrkB antagonist with anxiolytic and antidepressant activity in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 1846–1857. 10.1172/jci43992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin C. A., Tiffany S. T. (2002). Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction 97, 155–167. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J. M. (2006). Effects of oestrogen on cognition: what have we learned from basic research? J. Neuroendocrinol. 18, 787–795. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoudal G., Debanne D. (2003). Long-term plasticity of intrinsic excitability: learning rules and mechanisms. Learn. Mem. 10, 456–465. 10.1101/lm.64103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doncheck E. M., Urbanik L. A., DeBaker M. C., Barron L. M., Liddiard G. T., Tuscher J. J., et al. (2018). 17β-estradiol potentiates the reinstatement of cocaine seeking in female rats: role of the prelimbic prefrontal cortex and cannabinoid type-1 receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology 43, 781–790. 10.1038/npp.2017.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elman I., Karlsgodt K. H., Gastfriend D. R. (2001). Gender differences in cocaine craving among non-treatment-seeking individuals with cocaine dependence. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 27, 193–202. 10.1081/ada-100103705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernfors P., Bramham C. R. (2003). The coupling of a trkB tyrosine residue to LTP. Trends Neurosci. 26, 171–173. 10.1016/s0166-2236(03)00064-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S. M., Foltin R. W. (2010). Does the response to cocaine differ as a function of sex or hormonal status in human and non-human primates? Horm. Behav. 58, 13–21. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez S. M., Lewis M. C., Pechenino A. S., Harburger L. L., Orr P. T., Gresack J. E., et al. (2008). Estradiol-induced enhancement of object memory consolidation involves hippocampal extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and membrane-bound estrogen receptors. J. Neurosci. 28, 8660–8667. 10.1523/jneurosci.1968-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortress A. M., Fan L., Orr P. T., Zhao Z., Frick K. M. (2013). Estradiol-induced object recognition memory consolidation is dependent on activation of mTOR signaling in the dorsal hippocampus. Learn. Mem. 20, 147–155. 10.1101/lm.026732.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortress A. M., Kim J., Poole R. L., Gould T. J., Frick K. M. (2014). 17β-Estradiol regulates histone alterations associated with memory consolidation and increases Bdnf promoter acetylation in middle-aged female mice. Learn. Mem. 21, 457–467. 10.1101/lm.034033.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick K. M. (2012). Building a better hormone therapy? How understanding the rapid effects of sex steroid hormones could lead to new therapeutics for age-related memory decline. Behav. Neurosci. 126, 29–53. 10.1037/a0026660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick K. M. (2015). Molecular mechanisms underlying the memory-enhancing effects of estradiol. Horm. Behav. 74, 4–18. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick K. M., Fernandez S. M., Bennett J. C., Prange-Kiel J., MacLusky N. J., Leranth C. (2004). Behavioral training interferes with the ability of gonadal hormones to increase CA1 spine synapse density in ovariectomized female rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 3026–3032. 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2004.03427.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs R. B. (1998). Levels of trkA and BDNF mRNA, but not NGF mRNA, fluctuate across the estrous cycle and increase in response to acute hormone replacement. Brain Res. 787, 259–268. 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01511-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs R. B. (1999). Treatment with estrogen and progesterone affects relative levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein in different regions of the adult rat brain. Brain Res. 844, 20–27. 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01880-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham B. M., Milad M. R. (2013). Blockade of estrogen by hormonal contraceptives impairs fear extinction in female rats and women. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 371–378. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham B. M., Scott E. (2018). Effects of systemic estradiol on fear extinction in female rats are dependent on interactions between dose, estrous phase and endogenous estradiol levels. Horm. Behav. 97, 67–74. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresack J. E., Frick K. M. (2006). Post-training estrogen enhances spatial and object memory consolidation in female mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 84, 112–119. 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafenbreidel M., Twining R. C., Todd C. R., Mueller D. (2015). Blocking infralimbic basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF or FGF2) facilitates extinction of drug seeking after cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2907–2915. 10.1038/npp.2015.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R. A. (2012). Interaction of sex steroid hormones and brain-derived neurotrophic factor-tyrosine kinase B signalling: relevance to schizophrenia and depression. J. Neuroendocrinol. 24, 1553–1561. 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02365.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierski M. K., Sohrabji F. (2000). Region-and peptide-specific regulation of the neurotrophins by estrogen. Mol. Brain Res. 85, 77–84. 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00244-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierski M. K., Sohrabji F. (2001). Neurotrophin expression in the reproductively senescent forebrain is refractory to estrogen stimulation. Neurobiol. Aging 22, 311–321. 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00230-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski C. C., Davis S. J., Moyer J. R., Jr. (2012). Aging redistributes medial prefrontal neuronal excitability and impedes extinction of trace fear conditioning. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 1744–1757. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Foster T. C. (2002). 17β-estradiol benzoate decreases the AHP amplitude in CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 621–626. 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson E. B., Anker J. J., Gliddon L. A., Fons K. S., Carroll M. E. (2007). Effects of estrogen and progesterone on the escalation of cocaine self-administration in female rats during extended access. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 15, 461–471. 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez C. W., Bornovalova M. A., Reynolds E. K., Daughters S. B., Curtin J. J. (2007). Risk factors in the relationship between gender and crack/cocaine. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 15, 165–175. 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Fowler C. D., Young L. J., Yan Q., Insel T. R., Wang Z. (2001). Expression and estrogen regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene and protein in the forebrain of female prairie voles. J. Comp. Neurol. 433, 499–514. 10.1002/cne.1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Sareddy G. R., Wang J., Wang R., Li Y., Dong Y., et al. (2019). Neuron-derived estrogen regulates synaptic plasticity and memory. J. Neurosci. 39, 2792–2809. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1970-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch W. J., Roth M. E., Carroll M. E. (2002). Biological basis of sex differences in drug abuse: preclinical and clinical studies. Psychopharmacology 164, 121–137. 10.1007/s00213-002-1183-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch W. J., Roth M. E., Mickelberg J. L., Carroll M. E. (2001). Role of estrogen in the acquisition of intravenously self-administered cocaine in female rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 68, 641–646. 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00455-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeng L. Y., Cover K. K., Taha M. B., Landau A. J., Milad M. R., Lebrón-Milad K. (2017). Estradiol shifts interactions between the infralimbic cortex and central amygdala to enhance fear extinction memory in female rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 95, 163–175. 10.1002/jnr.23826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance-Katz E. F., Carroll K. M., Rounsaville B. J. (1999). Gender differences in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers—implications for treatment and prognosis. Am. J. Addict. 8, 300–311. 10.1080/105504999305703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthny C. R., Du X., Wu Y. C., Hill R. A. (2018). Investigating the interactive effects of sex steroid hormones and brain-derived neurotrophic factor during adolescence on hippocampal NMDA receptor expression. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2018:7231915. 10.1155/2018/7231915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B., Akama K., Alves S., Brake W. G., Bulloch K., Lee S., et al. (2001). Tracking the estrogen receptor in neurons: implications for estrogen-induced synapse formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 98, 7093–7100. 10.1073/pnas.121146898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad M. R., Zeidan M. A., Contero A., Pitman R. K., Klibanski A., Rauch S. L., et al. (2010). The influence of gonadal hormones on conditioned fear extinction in healthy humans. Neuroscience 168, 652–658. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno M., Yamada K., He J., Nakajima A., Nabeshima T. (2003). Involvement of BDNF receptor TrkB in spatial memory formation. Learn. Mem. 10, 108–115. 10.1101/lm.56003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montalbano A., Baj G., Papadia D., Tongiorgi E., Sciancalepore M. (2013). Blockade of BDNF signaling turns chemically-induced long-term potentiation into long-term depression. Hippocampus 23, 879–889. 10.1002/hipo.22144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer J. R., Jr., Thompson L. T., Disterhoft J. F. (1996). Trace eyeblink conditioning increases CA1 excitability in a transient and learning-specific manner. J. Neurosci. 16, 5536–5546. 10.1523/jneurosci.16-17-05536.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozzachiodi R., Byrne J. H. (2010). More than synaptic plasticity: role of nonsynaptic plasticity in learning and memory. Trends Neurosci. 33, 17–26. 10.1016/j.tins.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark M. E., Penry J. K. (1980). Catamenial epilepsy: a review. Epilepsia 21, 281–300. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1980.tb04074.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M. S., Anthony J. C. (2005). Risk of becoming cocaine dependent: epidemiological estimates for the United States, 2000–2001. Neuropsychopharmacology 30, 1006–1018. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M. M., Kuo A. G., Wu W. W., Sametsky E. A., Disterhoft J. F. (2003). Watermaze learning enhances excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 2171–2179. 10.1152/jn.01177.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis J. M., Dashew K. B., Mueller D. (2013). Neurobiological dissociation of retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memory. J. Neurosci. 33, 1271a–1281a. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3463-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis J. M., Fitzgerald M. K., Mueller D. (2014). Infralimbic BDNF/TrkB enhancement of GluN2B currents facilitates extinction of a cocaine-conditioned place preference. J. Neurosci. 34, 6057–6064. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4980-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Watson C. (2007). The Rat Brain Atlas in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Burlington, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peters J., Dieppa-Perea L. M., Melendez L. M., Quirk G. J. (2010). Induction of fear extinction with hippocampal-infralimbic BDNF. Science 328, 1288–1290. 10.1126/science.1186909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J., LaLumiere R. T., Kalivas P. W. (2008). Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J. Neurosci. 28, 6046–6053. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitha J., Pitha J. (1985). Amorphous water-soluble derivatives of cyclodextrins: nontoxic dissolution enhancing excipients. J. Pharm. Sci. 74, 987–990. 10.1002/jps.2600740916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk G. J., Mueller D. (2008). Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 56–72. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk G. J., Russo G. K., Barron J. L., Lebron K. (2000). The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in the recovery of extinguished fear. J. Neurosci. 20, 6225–6231. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06225.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera R., Yacobson I., Grimes D. (1999). The mechanism of action of hormonal contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptive devices. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 181, 1263–1269. 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70120-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E., Quirk G. J., Porter J. T. (2008). Fear conditioning and extinction differentially modify the intrinsic excitability of infralimbic neurons. J. Neurosci. 28, 4028–4036. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2623-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasahara K., Shikimi H., Haraguchi S., Sakamoto H., Honda S.-I., Harada N., et al. (2007). Mode of action and functional significance of estrogen-inducing dendritic growth, spinogenesis, and synaptogenesis in the developing Purkinje cell. J. Neurosci. 27, 7408–7417. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0710-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Akaishi T., Matsuki N., Ohno Y., Nakazawa K. (2007). β-Estradiol induces synaptogenesis in the hippocampus by enhancing brain-derived neurotrophic factor release from dentate gyrus granule cells. Brain. Res. 1150, 108–120. 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.02.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawai T., Bernier F., Fukushima T., Hashimoto T., Ogura H., Nishizawa Y. (2002). Estrogen induces a rapid increase of calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 950, 308–311. 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03186-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman H. E., Mercurio T. C., Goodman J. H., Wilson M. A., MacLusky N. J. (2003). Hippocampal excitability increases during the estrous cycle in the rat: a potential role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J. Neurosci. 23, 11641–11652. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11641.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra A. C., Torres-Díaz Y. M., Silva R. D., Puig-Ramos A., Menéndez-Delmestre R., Rivera-Bermúdez J. G., et al. (2014). Estrogen receptors mediate estradiol’s effect on sensitization and CPP to cocaine in female rats: role of contextual cues. Horm. Behav. 65, 77–87. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal M., Song C., Ehlers V. L., Moyer J. R., Jr. (2013). Learning to learn-intrinsic plasticity as a metaplasticity mechanism for memory formation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 105, 186–199. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M., Meyer E. M., Simpkins J. W. (1995). The effect of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement on brain-derived neurotrophic factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cortical and hippocampal brain regions of female Sprague-Dawley rats. Endocrinology 136, 2320–2324. 10.1210/en.136.5.2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabji F., Miranda R., Toran-Allerand C. D. (1995). Identification of a putative estrogen response element in the gene encoding brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 92, 11110–11114. 10.1073/pnas.92.24.11110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solum D. T., Handa R. J. (2002). Estrogen regulates the development of brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 22, 2650–2659. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02650.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Ehlers V. L., Moyer J. R., Jr. (2015). Trace fear conditioning differentially modulates intrinsic excitability of medial prefrontal cortex-basolateral complex of amygdala projection neurons in infralimbic and prelimbic cortices. J. Neurosci. 35, 13511–13524. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2329-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Moyer J. R., Jr. (2017). Layer and subregion-specific differences in the neurophysiological properties of rat medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 119, 177–191. 10.1152/jn.00146.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm J. F. (1987). Action potential repolarization and a fast after-hyperpolarization in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Physiol. 385, 733–759. 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. T., Moyer J. R., Jr., Disterhoft J. F. (1996). Transient changes in excitability of rabbit CA3 neurons with a time course appropriate to support memory consolidation. J. Neurophysiol. 76, 1836–1849. 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand C. D., Singh M., Sétáló G., Jr. (1999). Novel mechanisms of estrogen action in the brain: new players in an old story. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 97–121. 10.1006/frne.1999.0177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torregrossa M. M., Taylor J. R. (2013). Learning to forget: manipulating extinction and reconsolidation processes to treat addiction. Psychopharmacology 226, 659–672. 10.1007/s00213-012-2750-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining R. C., Tuscher J. J., Doncheck E. M., Frick K. M., Mueller D. (2013). 17β-estradiol is necessary for extinction of cocaine seeking in female rats. Learn. Mem. 20, 300–306. 10.1101/lm.030304.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M., Moss R. L. (1991). Electrophysiological evidence for a rapid membrane action of the gonadal steroid, 17 β-estradiol, on CA1 pyramidal neurons of the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 543, 148–152. 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91057-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley C. S. (2000). Estradiol facilitates kainic acid-induced, but not flurothyl-induced, behavioral seizure activity in adult female rats. Epilepsia 41, 510–515. 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley C. S. (2007). Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 47, 657–680. 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W. W., Adelman J. P., Maylie J. (2011). Ovarian hormone deficiency reduces intrinsic excitability and abolishes acute estrogen sensitivity in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 31, 2638–2648. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6081-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Hill R., Gogos A., van den Buuse M. (2013). Sex differences and the role of estrogen in animal models of schizophrenia: interaction with BDNF. Neuroscience 239, 67–83. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Nabeshima T. (2003). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB signaling in memory processes. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 91, 267–270. 10.1254/jphs.91.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan M. A., Igoe S. A., Linnman C., Vitalo A., Levine J. B., Klibanski A., et al. (2011). Estradiol modulates medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala activity during fear extinction in women and female rats. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 920–927. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-C., Yao W., Dong C., Yang C., Ren Q., Ma M., et al. (2015). Comparison of ketamine, 7, 8-dihydroxyflavone, and ANA-12 antidepressant effects in the social defeat stress model of depression. Psychopharmacology 232, 4325–4335. 10.1007/s00213-015-4062-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Zhang H., Cohen R. S., Pandey S. C. (2005). Effects of estrogen treatment on expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cAMP response element-binding protein expression and phosphorylation in rat amygdaloid and hippocampal structures. Neuroendocrinology 81, 294–310. 10.1159/000088448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Znamensky V., Akama K. T., McEwen B. S., Milner T. A. (2003). Estrogen levels regulate the subcellular distribution of phosphorylated Akt in hippocampal CA1 dendrites. J. Neurosci. 23, 2340–2347. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02340.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.