Abstract

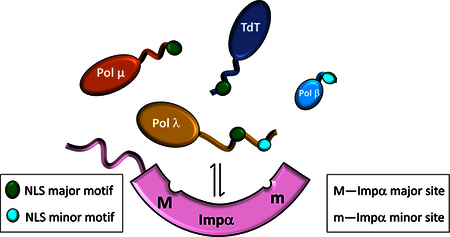

Despite the essential roles of pol X family enzymes in DNA repair, information about the structural basis of their nuclear import is limited. Recent studies revealed the unexpected presence of a functional NLS in DNA polymerase β, indicating the importance of active nuclear targeting, even for enzymes likely to leak into and out of the nucleus. The current studies further explore the active nuclear transport of these enzymes by identifying and structurally characterizing the functional NLS sequences in the three remaining human pol X enzymes: terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), DNA polymerase μ (pol μ), and DNA polymerase λ (pol λ). NLS identifications are based on Importin α (Impα) binding affinity determined by fluorescence polarization of fluorescein-labeled NLS peptides, X-ray crystallographic analysis of the ImpαΔIBB•NLS complexes, and fluorescence-based subcellular localization studies. All three polymerases use NLS sequences located near their N-terminus; TdT and pol μ utilize monopartite NLS sequences, while pol λ utilizes a bipartite sequence, unique among the pol X family members. The pol μ NLS has relatively weak measured affinity for Impα, due in part to its proximity to the N-terminus that limits non-specific interactions of flanking residues preceding the NLS. However, this effect is partially mitigated by an N-terminal sequence unsupportive of Met1 removal by methionine aminopeptidase, leading to a 3-fold increase in affinity when the N-terminal methionine is present. Nuclear targeting is unique to each pol X family enzyme with variations dependent on the structure and unique functional role of each polymerase.

Keywords: nuclear transport, DNA polymerase, DNA repair, crystal structure, protein import, microscopic imaging, NLS binding, Importin α

Synopsis

The mammalian DNA polymerase X enzymes play important roles in the maintenance of genome integrity, however participation in DNA repair requires nuclear localization. Here we report: the structural basis for nuclear import of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, DNA polymerase μ, and DNA polymerase λ (pol λ); apparent Kd values for binding to Impα as well as to the individual major and minor Impα binding pockets; and functional studies verifying the identities of the nuclear localization signals.

INTRODUCTION

DNA polymerase X (pol X) family enzymes fulfill a broad range of functions and contribute to multiple DNA repair pathways 1–4. However, despite the critical importance of nuclear localization of these enzymes, detailed information about their nuclear transport pathways has been limited and the identity of critical residues involved in nuclear transport has generally not been experimentally determined. Several web-based programs 5–9 provide useful predictions for potential nuclear localization signals (NLS) that mediate uptake via the classical Importin α/β system 10,11. However, these predictions can be inconsistent due to constraints on spacing between motifs, or adherence to specific sequence contexts. Although useful as starting points, identification of the NLS residues requires rigorous experimental verification. For example, bipartite NLS motifs have often been missed, presumably due to the atypical separation of the two component Importin α (Impα)-binding motifs 12–14.

It is increasingly recognized that altered subcellular distribution can lead to cellular dysfunction and disease 15–17. Ligase4 (LIG4) syndrome is an autosomal hereditary disorder leading to impairment of the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and V(D)J pathways. One of the common mutations identified in LIG4 syndrome patients, Lig4(R580X), lacks the C-terminal segment containing both the XRCC4-binding motif and the NLS, preventing nuclear localization 18. A mutation adjacent to the NLS sequence in ZNF687 has recently been identified as a cause of Paget’s disease 19. Amyotropic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is associated with mutations in the non-classical NLS region of the Fused in Sarcoma (FUS) protein 20,21. Variant forms of Xeroderma Pigmentosum have been determined to result from a mutation in the NLS sequence 22 or deletions of the C-terminal region containing the entire NLS 23 of the translesion repair enzyme DNA polymerase η. As more data become available associating altered localization with disease, it becomes increasingly critical to have a detailed understanding of the residues involved in nuclear localization to understand the role polymorphisms or post-translational modifications play in altering localization.

We recently demonstrated that DNA polymerase β (pol β), generally considered to lack a classical NLS, does in fact contain one at its far N-terminus. This NLS exhibits highly selective binding affinity for the minor binding pocket of Impα. We also found that this NLS contributes to the localization of the enzyme and is required to maintain a significant nuclear/cytosolic concentration gradient 24. In the case of pol β, the small size of the enzyme does not eliminate the requirement for active nuclear import since nuclear pol β so readily leaks out of the nucleus through the nuclear pore.

As a consequence of the issues outlined above, we have extended our studies to include the three other mammalian pol X enzymes: DNA polymerase mu (pol μ), DNA polymerase lambda (pol λ), and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), in order to better understand variations in nuclear import among this family of proteins. Previous reports identifying potential NLS sequences in these proteins were used 25–29, as well as identifications based on the software NLS Mapper 5. NLS sequences and their interactions with ImpαΔIBB (Impα lacking the Importin β binding domain) were subsequently characterized by X-ray crystallography and fluorescence polarization binding assays. We further substantiated the functional importance of the identified NLS sequences by fluorescence imaging studies of pol X-GFP adducts using U2OS cells.

RESULTS

Initial identification of Pol X NLS sequences

Initial identification of the pol X NLS sequences was based on available prediction software 5–9,30 summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. Most of these algorithms were able to identify the high scoring monopartite TdT NLS, but had more difficulty with pol μ and pol λ. Results obtained using NLSMapper 5, which we found to be the most user friendly and versatile, and which are consistent with most of the sequences identified using other software, are summarized in Table 1. Several of the identified sequences extend into the BRCT domain that follows the N-terminal residues or involve other folded regions of the protein. The resulting structural conflicts make these sequences less likely to act as functional NLSs, since a significant energetic penalty would be required to unfold the residues to make them available for Impα binding. For example, it has recently been demonstrated that the NLS segment of Influenza A RNA polymerase exists as an equilibrium of ordered and disordered states, with only the disordered state capable of binding to Impα 5. Only one of the sequences identified by NLS mapper, corresponding to the N-terminal residues of TdT, yielded a score above 5.0, the suggested default threshold for significance. Using these initial predictions, we designed a set of peptides based on the putative NLS sequences (see Methods) and used them in crystallization trials. In selecting these test peptides, we made an effort to ensure that the length was sufficiently inclusive to cover residues that might be part of the functional NLS but were not identified by the computational screen. In the case of pol λ, which had only very low scoring NLS sequences, NLS localization to the N-terminal region of the enzyme is also supported by reported biochemical and localization studies 27–29.

Table 1. NLS Mapper-predicted binding motifs.

The highest scoring representative sequences are shown; the NLS residues identified on the basis of binding interactions or crystallographic studies are in green, boldface font. Residues indicated in italicized, red font correspond to folded regions of the protein and are unlikely to interact with Impα.

| Protein | NLS Type | Sequence | residues | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPol μ | Monopartite | MLPKRRRAR | 1–9 | 2.5 |

| Bipartite | L2PKRRRARVGSPSGDAASSTPPSTRFPGV | 2–30 | 4.7 | |

| Bipartite | RELRRFSRKEKGLWLNSHGLFDPEQKTFF | 442–470 | 4.3 | |

| Bipartite | DPEQKTFFQAASEEDIFRHLGLEYLPPEQRN | 463–493 | 2 | |

| hPol λ | Monopartite | L7KAFPKRQKIH | 7–17 | 3.5 |

| Bipartite | K23VLAKIPRREEGEEAEEWLSSLRAHVVRTGI | 23–53 | 3.6 | |

| Bipartite | R4GILKAFPKRQKIHADASSKVLAKIPRRE | 4–32 | 3.1 | |

| hTDT | Monopartite | LSPRKKRPRQT | 9–19 | 11 |

| Bipartite | PRKKRPRQTGALMASSPQDIKFQDL | 11–35 | 4.6 | |

| Bipartite | RQFERDLRRYATHERKMILDNHALYDKTKRIFLK | 453–486 | 4 |

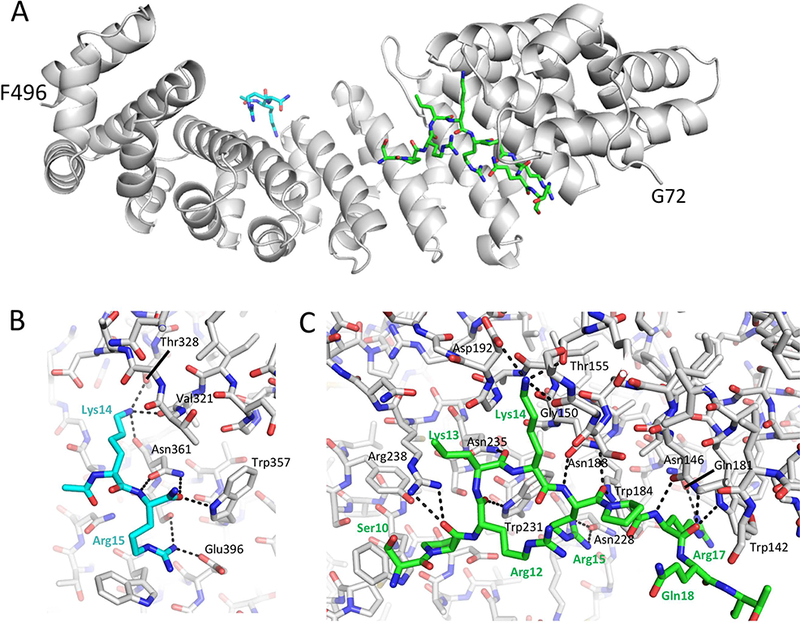

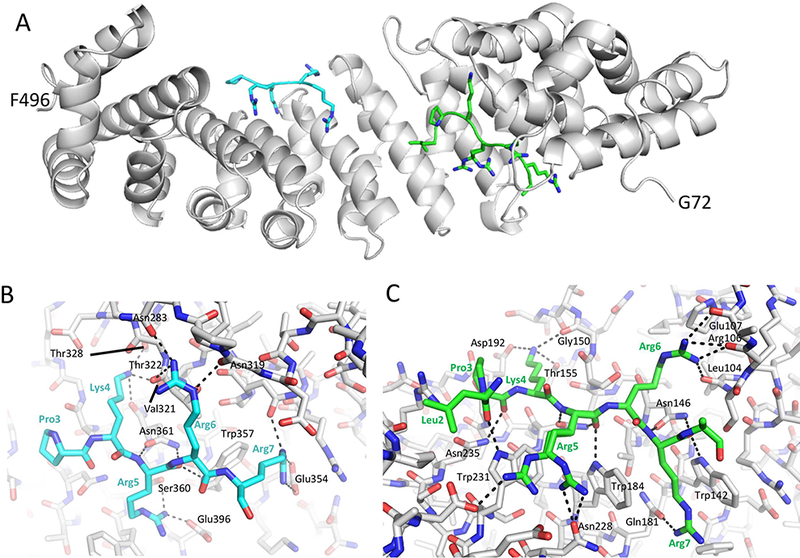

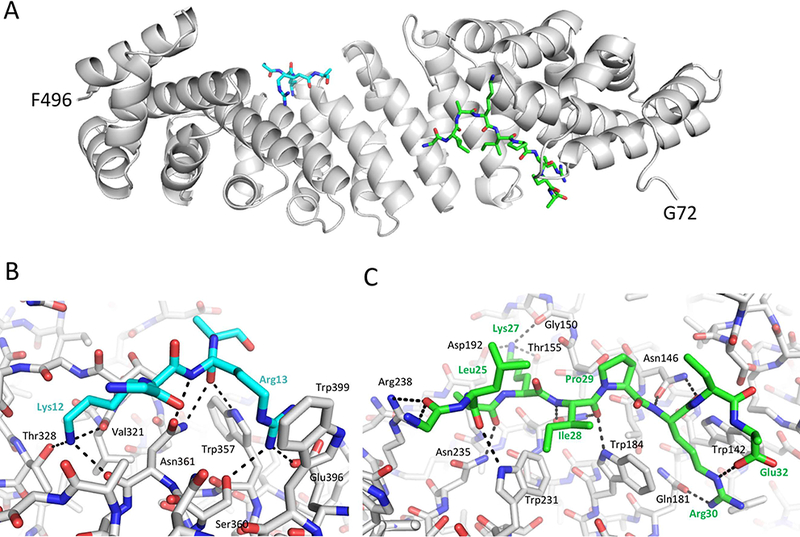

Crystallographic characterization of ImpαΔIBB-NLS complexes

We solved crystal structures for ImpαΔΙΒΒ in complex with the NLS peptides of TdT (Figure 1), pol μ (Figure 2), and pol λ (Figure 3). These structures demonstrate that TdT and pol μ contain monopartite Impα binding sequences, while the pol λ NLS complex utilizes a bipartite sequence, despite containing an overlapping monopartite consensus sequence that was preferred by NLSMapper and by several other NLS prediction programs (Supplementary Table S1). Alignments of the bound NLS sequences with the Impα binding pockets are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. For the sequences corresponding to TdT and pol μ, the NLS peptides are observed to interact primarily with the major binding pocket of Impα, however weak electron density is also observed in the minor site that was modeled with partial occupancy by shorter fragments of the NLS monopartite sequence. Simulated annealing fo-fc difference maps contoured at 2.5 sigma for the TdT, pol μ and pol λ peptides bound at the major and minor sites of Impα are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 1.

Crystallographic complex of ImpαΔIBB with the TDT NLS peptide. A) structural overview. B) H-bonding interactions in the minor Impα binding pocket, and C) the major binding pocket. Sidechain positions for only Lys14 and Arg15 are resolved in the minor binding pocket, while 10 residues are resolved in the major binding pocket.

Figure 2.

Crystallographic complex of ImpαΔIBB with the pol μ NLS peptide. A) structural overview showing the monopartite sequence occupying both the major and minor binding Impα binding pockets. B) H-bonding interactions in the minor site. C) H-bonding interactions in the major site.

Figure 3.

Crystallographic complex of ImpαΔIBB with the bipartite pol λ NLS peptide. A) structural overview; B) H-bonding interactions in the minor binding pocket; C) H-bonding interactions in the major binding pocket.

The TdT NLS peptide complex at the major binding pocket of Impα involves 10 residues (Ser10 Thr19); additional electron density at the minor binding pocket was fit corresponding to partial occupancy by four residues, with only two sidechains, corresponding to Lys14 and Arg15 that could be refined (Figure 1). We identified 16 H-bond interactions with major binding pocket residues and 8 H-bonds with minor binding pocket residues (defined by CO---N distance < 3.5 Å).

Although the pol μ test peptide (L2PKRRRARVGSPSGDAASSTPPSTRFPGV) includes residues suggested by NLS Mapper to form a bipartite complex, the structure shows only monopartite complexes that form at both the major (7 residues) and minor (5 residues) Impα binding pockets (Figure 2 A). A total of 17 or 18 H-bonds – depending on the conformation of Arg5, were identified with Impα residues in the major binding pocket, while electron density for five residues is observed at the minor site pocket, forming 15 intermolecular H-bonds (Figure 2 B, Figure 2 C).

We identified the pol λ NLS using a peptide that contains both the monopartite and lower-scoring bipartite sequences suggested by NLS Mapper (R4GILKAFPKRQKIHADASSKVLAKIPRRE). As indicated in Table 1, the higher-scoring bipartite sequence would include residues determined to form part of the pol λ BRCT domain 32. The observed crystal structure for the ImpαΔΙΒΒ-pol λ NLS complex (Figure 3) corresponds to the lower-scoring bipartite NLS, in which the major site forms 14 intermolecular H-bonds, and the minor site 8 intermolecular H-bonds. In contrast with the behavior of TdT and pol μ in which the major and minor binding pockets compete for common residues in the monopartite NLS, the pol λ NLS interacts with both the major and minor binding pockets simultaneously. However, based on the observed electron density, the occupancy of the minor pocket is estimated as ~ 70%, compared with approximately full occupancy of the major site.

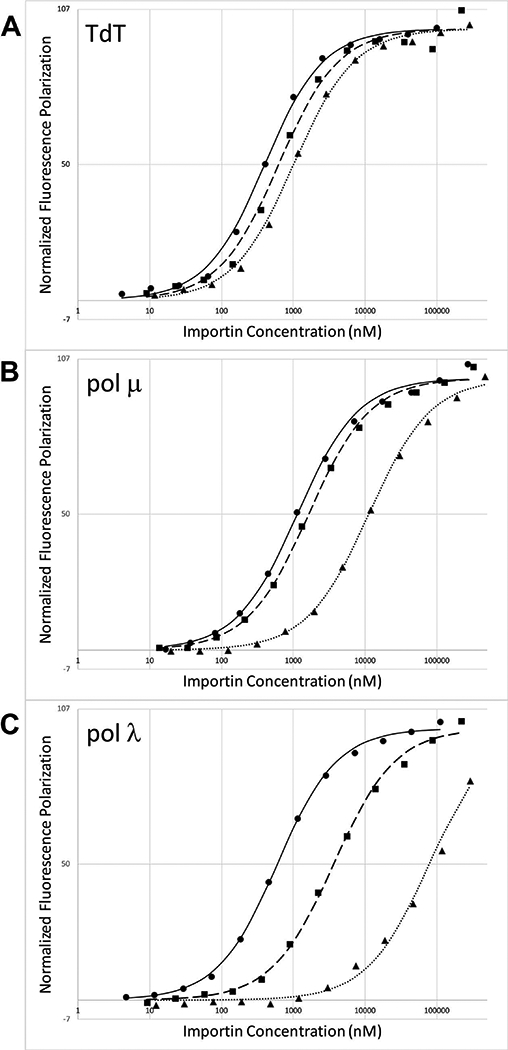

Affinity and selectivity of the pol X NLS-Impα interactions

We determined affinities of the identified pol X NLS sequences for Impα by fluorescence polarization measurements using fluorescein-NLS peptide adducts (Figure 4, Table 2). These binding experiments were performed using ImpαΔIBB, as well as two constructs in which either the major or minor binding site was blocked: major-site blocked analog, ImpαΔIBB(W184R,W231R); minor site-blocked analog, ImpαΔIBB(W357R,W399R) 13,24. Several previous studies have utilized Impα mutants containing mutated Asp192 or Glu396 14,33 to define subsite binding specificity, although other mutational strategies have also been followed 34. However, we were concerned that single site mutations might be insufficient to fully block these interactions. For example, the N-terminal IBB domain remains bound to the major Impα binding pocket in a D192A,E396A double mutant (pdb: 3tpo (33)). The Trp→Arg Impα mutants were designed to fully block binding at the major or minor binding pockets by: 1) removing Trp sidechains that stack against major site residues in the P3 and P5 sites or minor site residues in the P2’ and P4’ sites; 2) removing the corresponding H-bond interactions between the Trp NHε and the NLS backbone carbonyl oxygens; and 3) creating an unfavorable electrostatic environment for positively charged NLS sidechains. This strategy thus counters each of the three classes of Impα-NLS interaction identified by Conti et al. 35, viz, “Hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions between [Impα] and the NLS backbone and side chains are likely to be the primary determinants of affinity, with specificity arising from electrostatic complementarity.” In the present study, we have further characterized the major- and minor-site mutants crystallographically in order to further check that the Trp→Arg substitutions introduced were not causing more extensive structural perturbations. As is apparent from the data in Supplementary Figure S2, and Supplementary Table S3 (deposited under pdb ID codes 6D7M and 6D7N), not only do the mutations not introduce long-range structural perturbations, but they in fact exert negligible local structural perturbations in the regions containing the substitutions. Thus, the effects of the mutations are targeted to the NLS interactions and do not affect binding via structural perturbations. These structural results are consistent with previously published results demonstrating, e.g., that the bipartite XRCC1 NLS binding affinity to the major site mutant was equivalent to the binding affinity of the isolated minor-site motif peptide 13.

Figure 4.

Binding of the pol X NLS peptides to Impα constructs. A) TdT NLS peptide—SHLSPRKKRPRQTGAK-FITC; B) pol μ NLS peptide—MLPKRRRARVGGK-FITC; C) pol λ NLS peptide—KAFPKRQKIHADASSKVLAKIPRREEGK-FITC. For each panel, the fluorescence polarization studies of the fluorescein-labeled peptide as a function of Impα concentration correspond to: ImpαΔIBB (solid circles, solid line); minor site-mutated ImpαΔIBB (W357R,W399R) (solid squares, dashed line); or major site mutated ImpαΔIBB (W184R,W231R) (solid triangles, dotted line). Experiments were run in duplicate and curve-fitting allowed determination of Kd and 95% confidence interval.

Table 2. Pol X NLS dissociation constants.

Kd values with 95% confidence interval are in columns 3, 4, and 5 for the interaction of the indicated Impα protein with the labeled NLS peptide in column 2.

| pol X | NLS Peptidea | Dissociation constant (μM)b |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImpαΔIBB | ImpαΔIBB minor site mutant |

ImpαΔIBB major site mutant |

||

| TdT | SHLSPRKKRPRQTGAK-FITC | 0.349 ± 0.036 | 0.581 ± 0.111 | 0.964 ± 0.083 |

| pol μ | LPKRRRARVGGK-FITC | 3.52 ± 0.26 | 4.48 ± 0.28 | 29.3 ± 2.0 |

| pol μ | MLPKRRRARVGGK-FITC | 1.09 ± 0.11 | 1.59 ± 0.15 | 11.2 ± 0.9 |

| pol λ | KAFPKRQKIHADASSKVLAKIPRREEGK-FITC | 0.548 ± 0.042 | 3.61 ± 0.39 | 78.9 ± 16.5 |

Surprisingly, the fluorescein-labeled TdT NLS peptide exhibits fairly similar affinities for both sites (Figure 4 A, Table 2), with a major site/minor site affinity ratio of only 1.7, consistent with the possibility that either binding pocket may mediate nuclear transport. The electron density in the minor site was only sufficient to allow modeling of the Lys14 and Arg15 sidechains – a sequence typical of minor-site binding motifs 36. Minor site interaction with a Lys-Lys-Arg sequence (corresponding to pol μ residues 13–15) has also been observed, but much less frequently 36,37. Since the major and minor binding pockets compete for the TdT NLS with similar binding affinities, it is not surprising that blocking either site selectively has only a modest effect on the observed binding affinity. Potential binding interactions to regions other than the major or minor Impα binding pockets are negligible (Supplementary Table S5).

The dissociation constants measured for the pol μ NLS using a fluorescein-labeled pol μ peptide (Figure 4 B, Table 2) indicate that the affinity for both the major and minor binding pockets of Impα is relatively weak (Table 2). Extensive crystallographic characterizations as well as numerous binding studies support the conclusion that the interaction of Impα with the basic NLS recognition sequences is typically augmented by non-specific interactions of residues preceding the consensus binding motif 38; however, for pol μ the NLS is positioned so near the N-terminus that the contributions of such interactions are minimal. A comparison of the NLS Mapper predictions for pol μ NLS sequences of various species (Supplementary Table S4) reveals that all of the very low scoring sequences are positioned very close to the N-terminus, while those located a few residues farther from the end correspond to much higher scores. Furthermore, all of the low scoring sequences nearest the N-terminus begin with a Met-Leu-Pro sequence, which has a low cleavage probability by both the E. coli and human methionine aminopeptidases 39, while the higher scoring sequences generally contain residues a position 2 that will allow cleavage by this enzyme. A comparison of the binding affinity of the NLS sequences with and without Met1 (Table 2) demonstrates that retaining Met1 reduces the dissociation constants by ~ 3-fold. This result further supports the identified pol μ NLS and, more generally, illustrates the importance of the uncleaved Met1 for NLS sequences positioned very close to the protein N-terminus.

Analysis of the Impα binding affinities for fluorescein-labeled pol λ peptides is consistent with a cooperative bipartite interaction (Figure 4 C, Table 2). The cooperativity triggered by the NLS motifs binding to both major and minor pockets leads to an apparent overall dissociation constant of 0.548 μM compared with the 3.61 μM and 78.9 μM Kds for the major and minor pockets, respectively (Table 2).

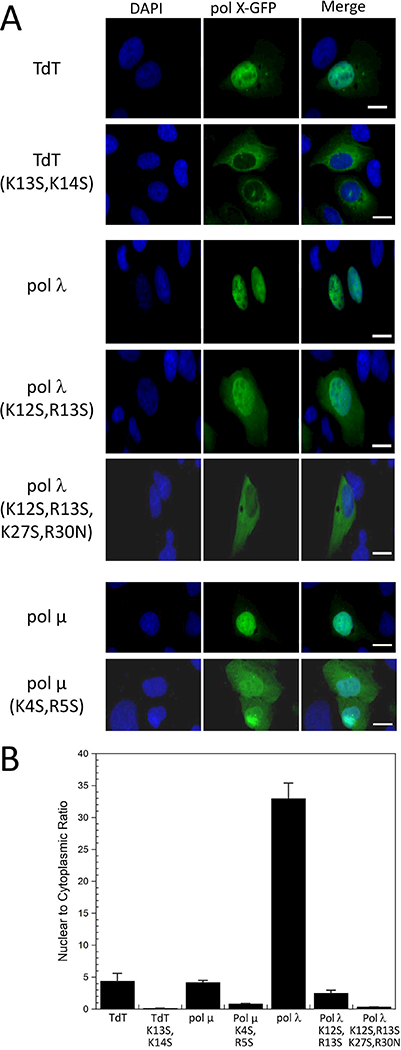

Subcellular distribution of pol X enzymes

We evaluated the subcellular distribution of the polymerases in U2OS cells transfected with GFP-adducts containing either the wild-type polymerases or variants in which important binding residues in the NLS were mutated. The nuclear/cytosolic intensity ratios are summarized in Table 3, and illustrative fluorescence data is shown in Figure 5. As outlined in Methods, the mutations were selected in order to substitute the primary binding residues identified from the crystal structures with hydrophilic Ser residues not expected to interact significantly with Impα. In the case of TdT, both Lys13 and Lys14 are replaced by Ser residues in order to eliminate the two alternate binding modes in which either one could interact with the Lys-selective P2 (major) site and P1’ (minor) site positions. The nuclear/cytosolic ratios for the TdT and pol μ GFP adducts are considerably lower than the ratio observed for pol λ, however most of this difference arises as a consequence of dividing by the very low cytosolic value obtained in the pol λ study. Differences may also arise due to perturbations related to the presence of the adducted GFP and likely also depend on cell type, as well as the possibility that the somewhat smaller TdT and pol μ enzymes may leak through the nuclear pore 40. In studies of pol λ distribution in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, a ratio of 8 obtains (unpublished observations). Overall, these results confirm the identities of the crystallographically-identified NLS sequences and support their importance in determining the subcellular distribution of these polymerases. Since TdT and pol μ have more specialized roles in DNA transactions 1,3,4,41, the lower nuclear/cytosolic ratios may represent a true variation, and additional studies in other cell types and under other conditions will be required to more completely evaluate how these variations influence subcellular localization.

Table 3.

Nuclear/Cytosolic concentration ratios of pol X enzymes

| Protein | N/C ± SEM | No. of cells |

|---|---|---|

| TdT-GFP | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 42 |

| TdT(K13S,K14S)-GFP | 0.16 ± 0.006 | 150 |

| Pol μ-GFP | 4.2 ± 0.32 | 82 |

| Pol μ(K4S,R5S)-GFP | 0.85 ± 0.037 | 73 |

| GFP-pol λ | 33.0 ± 2.4 | 60 |

| GFP-pol λ(K12S,R13S) | 2.5 ± 0.043 | 34 |

| GFP-pol λ(K12S,R13S,K27S,R30N) | 0.33 ± 0.014 | 85 |

Figure 5.

Fluorescence images of U2OS cells containing pol X-GFP fusion adducts A) Illustrative images of cells containing the TdT, pol μ and pol λ GFP adducts. The images correspond to the adducts formed with the wild-type enzymes, as well as to the variants containing residue substitutions in the identified NLS sequences. The three columns correspond to: cells stained with 4’,6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (column 1); the GFP signal arising from the pol X-GFP adducts indicated on the left-hand side of the panel (column 2); the merged fluorescence images (column 3). B) Nuclear/cytosolic intensity ratios of the fluorescence signals, corresponding to the data contained in Table 3. As is apparent from the figure, not all of the cells express the pol X-GFP adducts.

DISCUSSION

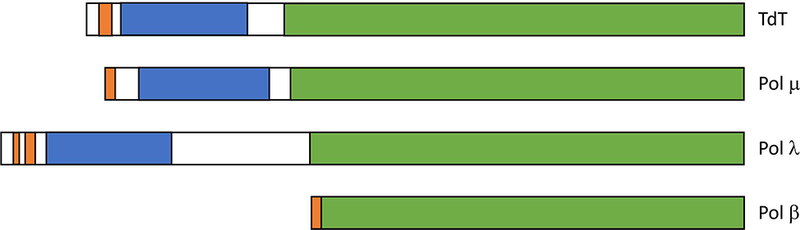

The DNA repair functions of the pol X enzymes require nuclear localization 16. Although initial identification of nuclear localization signals can be made using web-based software, reliable identification of these sequences requires additional characterization and quantitation. Of the three pol X NLS enzymes studied here, NLS Mapper as well as other prediction programs that we evaluated (Supplementary Table S1) correctly identified the high-affinity monopartite NLS for TdT, while in most cases either missed or required very low thresholds to identify pol μ and pol λ NLS sequences. A pol μ bipartite NLS sequence identified by NLS Mapper does not bind Impα, and if bound, the overlap of the C-terminal residues of the identified sequence with the N-terminus of the pol μ BRCT domain would be structurally problematic 42, but is in agreement with the initially proposed sequence 25. The pol λ bipartite NLS complex identified crystallographically was either not identified by some software programs or, as indicated in Table 1, corresponded to a very low scoring sequence, but was in the N-terminal region previously shown to contain an NLS 27–29. Similarly, we recently determined that pol β, generally thought to lack a nuclear localization signal, contains a functional NLS at its N-terminus, and that XRCC1 contains a bipartite NLS separated by an atypically long internal linker that is not readily identified by many NLS software analysis programs 13,24. These results illustrate that nuclear localization can be achieved through a variety of sequences and sequence contexts which prediction software may fail to recognize or evaluate as less probable (Figure 6). Therefore, there is a need to identify and evaluate such sequences at a level that goes beyond initial, software-based identification. In addition, the increasing availability of detailed information relating polymorphisms or mutations to pathological conditions makes it useful to identify the residues that support protein function, mediate interactions or cellular localization which may provide insight into the basis for the effects of these sequence variations.

Figure 6.

NLS positions in human pol X enzymes. Positions of the NLS (orange), BRCT (blue), and pol β-like regions (green) are indicated. TdT and pol μ contain a monopartite NLS that targets primarily the major binding pocket of Impα, the pol β NLS targets the Impα minor site pocket, and pol λ uses a bipartite NLS. Positions of the nuclear localization signals were determined here and previously24.

The present study completes the characterization of the pol X NLS sequences (Figure 6). Previous reports of the subcellular localization of these enzymes have been variable. Several studies have been reported on the two splice variants of murine TdT 43–46. Although both forms contain the predicted N-terminal NLS signal, only the shorter form lacking a C-terminal 20-residue insertion (TdTS), was observed to localize in the nucleus 44. It was subsequently determined that the longer variant, for which a human analog has not been reported, is considerably less stable at physiological temperatures 45, and this reduced stability was suggested as a possible explanation for its lack of nuclear accumulation 46. An analogous relationship between stability and nuclear accumulation has been suggested for XRCC1, although in this case, stabilization is suggested to result from XRCC1 phosphorylation 47. Surprisingly, Repasky et al. 43 have reported that nuclear localization of murine TdTS in murine 3TGR cells is observed even for mutants lacking the NLS, BRCT, and C-terminal segments. This result is inconsistent with the localization data obtained here for hTdT in U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Unfortunately, no quantitative localization data was included, limiting further evaluation of the basis for these differences.

The nuclear localization of pol μ obtained in the present study is consistent with a previous report 41. The pol μ monopartite NLS sequence is highly basic and able to interact with the major and minor binding pockets of Impα, however the binding affinity for both was in the micromolar range. We attribute this weakness primarily to the proximity of the pol μ NLS to the protein N-terminus, as also suggested by NLS mapper analysis of pol μ from other species (Supplementary Table S4). Consistent with this conclusion, we found that those examples in which the NLS sequence begins very close to the protein N-terminus invariably contained a Leu-Pro at positions 2–3, making the protein a poor substrate for methionine aminopeptidase 39. Inclusion of the N-terminal Met1 residue in the NLS sequence results in increased binding affinity that can be attributed to an interaction of the Met1 backbone at the P-1 position of the major site. The NLS binding affinity required to support nuclear import has been subject to controversy 48, and studies of shorter NLS peptides that lack large extensions potentially capable of additional, non-specific binding have generally yielded Kd values in the range of 0.1 – 10 μM 49–52. As discussed recently, cooperative Impα binding of the major- and minor-site NLS motifs – and potentially other motifs contained in the cargo protein 10, provides a strategy that is well suited to produce both high affinity binding and intra-nuclear dissociation involving minor site-directed dissociation factors 13.

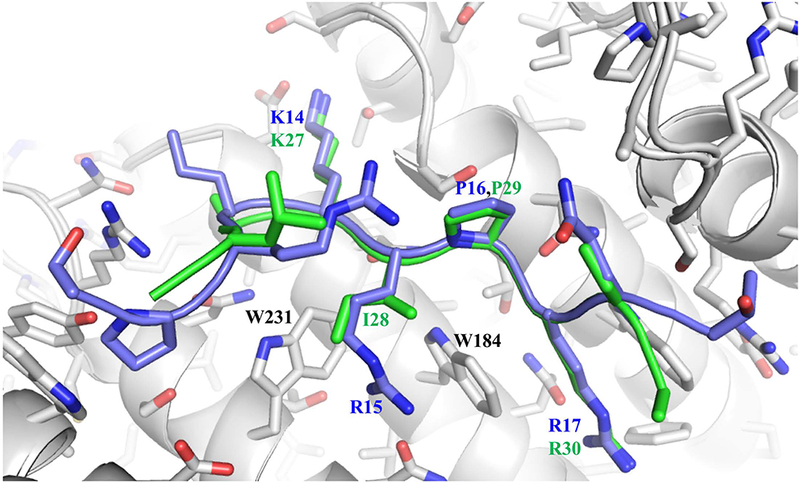

Of the four mammalian enzymes, only the pol λ NLS utilizes a bipartite structure and in the cell-types investigated, shows the greatest extent of nuclear localization; these results are consistent with earlier reports indicating that the NLS is located in the N-terminal region of the enzyme 27–29. In the pol λ-Impα complex, the AKIPR motif found in the major binding pocket lacks a basic residue at position P3 that is commonly encountered at this position 36,53 (Supplementary Table S2). Nevertheless, hydrophobic residues at this position have been found in a number of instances including the TPX2 NLS 14, the androgen receptor NLS 49, the phospholipid scramblase 1 NLS 54, and histone acetyltransferase MOF 55. The latter two examples also contain an Ile residue at position P3. As illustrated by the comparison in Figure 7, the Ile side chain also supports favorable interactions with the Trp residues in the binding pockets. For pol λ, the bipartite sequence with an Ile at the P3 position of the major site motif is apparently favored over a monopartite consensus sequence (K12RQK) also contained in the test peptide (Table 1). Bipartite sequences that contain internal, disordered linking segments, offer inherent advantages of affording a higher affinity binding interaction due to the cooperative binding of the minor and major pocket-directed motifs, while providing a more efficient unloading strategy involving minor site-targeted unloading factors such as Nup50 13,56. Although frequently discussed as a displacement mechanism, competition for the minor binding pocket of Impα is ultimately determined by site availability that results from the lower affinity binding to the minor site pocket. The greater availability of the unliganded minor site in this case is directly demonstrated by electron density observed in the complex corresponding to ~ 70% occupancy of the minor binding pocket. Thus, as discussed previously, the bipartite interaction motif leads to a significant enhancement of the binding affinity to sub-micromolar Kd values (Table 1), while providing a partially dissociated complex that facilitates substitution of the minor site pocket with minor pocket-directed cargo unloading factors.

Figure 7.

Overlaid structures of the TdT NLS (blue) and pol λ NLS (green) peptides in the major binding pocket of Impα (gray). The pol λ Ile residue at position P3 is able to interact effectively with Trp231 and perhaps Trp184.

The DNA repair system is designed with a substantial level of redundancy, allowing repair to proceed when optimal repair proteins may be less available. There is significant overlap of repair pathways utilizing pol β and pol λ 57, so that differences in nuclear concentrations may influence polymerase selection. These enzymes have different error profiles, e.g. the tendency to incorporate ribonucleotides 58. As shown here, in U2OS cells the ratio of nuclear/cytosolic pol λ was determined as ~ 33:1. This compares with ratios of ~ 3:1 for pol β 24—similar results for these two polymerases have recently been reported by Stephenson et al. 28. Although the involvement of these enzymes in the repair process is also dependent on expression levels as well as recruitment of other interacting repair factors such as XRCC1 59 and Ku 60, differences in nuclear localization may influence the net contribution that each of these repair enzymes makes. Further, the low nuclear/cytosolic gradient of pol β makes its nuclear concentration more subject to fluctuations of the cytosolic pol β pool such as CHIP-mediated degradation 61. Finally, the identities of these NLSs provide a basis for understanding the potential relationship of NLS polymorphisms to pathological conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Peptides used for crystallization studies included the NLS-Mapper-identified sequences for TdT: Ac-S7HLSPRKKRPRQTGAL, pol μ: Ac-L2PKRRRARVGSPSGDAASSTPPSTRFPGV, and pol λ: Ac-R4GILKAFPKRQKIHADASSKVLAKIPRRE, and were obtained from Genscript at a purity level of >90%. With the exception of the pol μ peptide, NLS Mapper-identified sequences that extended into the succeeding BRCT domain were not investigated. The fluorescein-labeled NLS peptides for TdT: SHLSPRKKRPRQTGAK-FITC; pol μ: LPKRRRARVGGK-FITC and MLPKRRRARVGGK-FITC; and pol λ: KAFPKRQKIHADASSKVLAKIPRREEGK-FITC, used in the fluorescence polarization assays were also obtained from Genscript at a purity level of >90%.

Impα major and minor binding pocket variants

Studies of Impα containing mutations in major or minor binding pockets were used to identify the binding pocket selectivity of NLS sequences. In order to block Impα major or minor binding pocket NLS interactions, we utilized W184R/W231R major-site or W357R/W399R minor-site variants. Although Trp residues are often used by proteins to stabilize the hydrophobic core, the Impα binding sites utilize solvent-exposed Trp residues that intercalate with the sidechains of the NLS peptides and form H-bonds with the NLS backbone. In order to eliminate these Trp-dependent interactions, we prepared His-tagged murine Importin α1 with the Importin β binding domain (IBB) deleted (ImpαΔIBB), its major pocket variant: ImpαΔIBB(W184R/W231R), and its minor pocket variant: ImpαΔIBB(W357R/W399R) as described previously 13,24, and have now characterized these constructs crystallographically (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3). Supplementary Table S5 shows that the often-used D192K and E396R ImpαΔIBB mutants give similar binding results and that the double mutant exhibits poor affinity for the fluorescein-labeled peptides.

Crystallization

ImpαΔIBB (15 mg/ml) was in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.8, 125 mM NaCl, and 5 mM DTT. Each NLS peptide was added to the solution at a molar excess of 1.25:1 prior to crystallization. All crystals were grown using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 2 μl of the ImpαΔIBB/peptide solution with the mother liquor solution and equilibrating over 900 μL of mother liquor. For the complexes with the TdT and pol μ peptides, the mother liquor consisted of 0.7 or 0.8 M sodium citrate (respectively), and 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0. For pol λ, 1.4–1.5 M ammonium sulfate and 0.1 M Bis-tris propane (BTP) pH 7.0 was used.

Data Collection and Processing

For data collection, crystals of TdT, pol μ and pol λ were transferred into a cryo solution consisting of the mother liquor plus 23%, 23% and 20% glycerol respectively. Data were collected at 100 K at the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline at the Advanced Photo Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Data were processed using HKL2000 62. PHASER 63 was used to solve the molecular replacement with the coordinates of importin from PDB idcode 5E6Q as a starting model 13. The same Rfree test set as found in 5E6Q was utilized for the Rfree calculations and extended to higher resolution for each data set. Model building and refinement were carried out using Phenix 64 and Coot 65. The final structures displayed good geometry with 100% of the residues in the allowed region of the Ramachandran plot as assessed by Molprobity 64. The structure statistics are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| data set | TdT | Pol λ | Pol μ |

|---|---|---|---|

| unit cell | a=78.7, b=89.5, c=100.3 α=β=γ= 90° |

a=78.8, b=90.4, c=101.5 α=β=γ= 90° |

a=79.0, b=89.82, c=99.54 α=β=γ= 90° |

| # of crystals | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Space Group | P212121 | P212121 | P21212 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–2.2 | 50.0 – 2.1 | 50.0 – 2.0 |

| # of observations | 247,511 | 225,666 | 318,924 |

| unique reflections | 36,690 | 41,954 | 48,426 |

| Rsym(%)(last shell)1 | 7.1 (32.8) | 7.1 (34.7) | 6.9(38.0) |

| I/σI (last shell) | 10.8 (3.3) | 13.6 (2.6) | 11.9 (2.5) |

| Mosaicity range | 0.2 – 0.5 | 0.4 – 0.5 | 0.2–0.4 |

| completeness(%) (last shell) | 97.3 (76.1) | 96.9 (78.9) | 97.4 (74.1) |

| Refinement statistics | |||

| Rcryst(%)2 | 16.3 | 16.8 | 16.7 |

| Rfree(%)3 | 19.1 | 19.7 | 19.9 |

| # of waters | 277 | 251 | 318 |

| Average B (Å) | |||

| importin | 42.7 | 39.2 | 37.6 |

| peptide | 45.6 | 45.4 | 34.1 |

| solvent | 48.0 | 43.9 | 44.7 |

| r.m.s. deviation from ideal values | |||

| bond length (Å) | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.008 |

| bond angle (°) | 1.13 | 0.69 | 1.08 |

| dihedral angle (°) | 11.77 | 13.12 | 11.14 |

| Ramachandran Statistics4 | |||

| favored (98%) | 98.4 | 97.2 | 97.7 |

| allowed (>99.8%) | 1.6 | 2.8 | 2.3 |

Rsym = ∑ (| Ii - < I>|)/ ∑(Ii) where Ii is the intensity of the ith observation and <I> is the mean intensity of the reflection.

Rcryst = ∑|| Fo| - | Fc ||/ ∑| Fo| calculated from working data set.

Rfree was calculated from 5% of data randomly chosen not to be included in refinement.

Ramachandran results were determined by MolProbity.

Peptide binding measurements

Apparent peptide dissociation constants were determined based on fluorescence polarization measurements using the fluorescein-labeled peptides as previously described 13, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated 66. We found that inclusion of 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin is useful for the NLS studies since it reduces non-specific binding of the positively charged peptides to test tubes. Fluorescence polarization was read at room temperature with the POLARstar Omega microplate reader (BMG Labtech) using excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm. Protein concentrations were determined by the Edelhoch procedure 67.

Cell lines and plasmids

U2OS human osteosarcoma cells were a gift from Dr. Joel Andrews at the University of South Alabama Mitchell Cancer Institute. The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Mycoplasma testing was performed routinely using a MycoAlert® Mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza) and results were negative.

The coding sequence for human pol λ with an N-terminal flag tag and flanking attL recombination sites was purchased from Genscript. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent) was used to create two pol λ NLS variants, one replacing residues 12 and 13 with serines (K12S,R13S), and another replacing residues 12, 13, and 27 with serines and residue 30 with asparagine (K12S,R13S,K27S,R30N). These mutations preserve the hydrophilic nature of the residues while eliminating specific interactions with Impα. The wild-type and mutant NLS cDNA were then moved into the N-terminal GFP containing pcDNA-DEST53 vector utilizing Gateway technology (Life Technologies). This resulted in the three sequence-verified mammalian cell expression vectors used in this study, pDEST53 pol λ, pDEST53 pol λ(K12S,R13S), and pDEST53 pol λ(K12S,R13S,K27S,R30N). The coding sequence for human pol μ and human TdT in a pCDNA3.1 backbone with a C-terminal GFP tag were purchased from Genscript, along with the same vectors expressing the pol μ(K4S,R5S) NLS variant and the TdT(K13S,K14S) variant.

Expression of the pol X family protein fusions was verified by screening for the presence of GFP by western blotting (Supplementary Figure S3). U2OS cells were seeded in 100 mm dishes at 106 cells/dish and grown until 70% confluent. Cells were then transfected with 5 μg of plasmid DNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) at a 1:4 ratio of DNA to Lipofectamine. 24 h after transfection cells were washed in PBS and collected by scraping. Cell were then resuspended in two volumes of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 0.3% NP-40) containing 1× Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitors and incubated on ice for 30 min. After agitating the tubes briefly, the lysates were centrifuged at 20,800×g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant fraction was removed. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard. 60 μg of prepared lysates from each cell line were separated by 4–20% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane in a TurboBlot apparatus (BioRad). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBS-T) and probed with the anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (1∶500 dilution; abcam). Detection was by ECL following incubation with secondary antibody conjugated to HRP. The blot was stripped by incubating with ReView™ buffer as suggested by the manufacturer (Amresco), then washed twice for 30 min with room temperature TBS-T. After stripping, the membrane was then probed with anti-Tubulin (1∶10,000; Sigma-Aldrich) as a loading control.

Fluorescence Microscopy

For nuclear localization studies, U2OS cells were seeded at 10,000 cells per chamber in an 8-chamber slide Nunc Lab-Tek (Fisher Scientific) in 0.25 ml of growth medium. Cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 pol μ-GFP, pcDNA3.1 pol μ(K4S,R5S)-GFP, pcDNA3.1 TdT-GFP, pcDNA3.1 TdT(K13S,K14S)-GFP, pDEST53 pol λ, pDEST53 pol λ(K12S,R13S), and pDEST53 pol λ(K12S,R13S, K27S,R30N) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) at a 1:4 ratio of DNA to Lipofectamine. 24 h after transfection cells were fixed with a 3.7% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution (Thermo Scientific) for 10 min at room temperature and washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, HyClone). After fixation, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, then washed 3 times in PBS. The whole cell was then stained with HCS CellMask™ Deep Red Stain per manufacturer’s protocol (Life Technologies), and nuclei were stained with NucBlue® Fixed Cell Stain ReadyProbes™ (Life Technologies) for 5 min.

Fluorescent images were acquired with a 20X C-Apochromat (NA 0.75) air immersion objective coupled to a Nikon A1rsi laser scanning confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments). Multichannel images were collected using 405, 488, and 647 nm laser lines to acquire three fluorescent channels in addition to transmitted DIC. 2-D images were acquired and DAPI staining was used to select the best focal plane for nuclear imaging. Images were acquired at 1024×1024 resolution with a pinhole of 67.69 μm, a zoom of 1.0. NIS-Elements 4.51 software was used for all image acquisition and analysis.

Nuclear to cytoplasmic (N/C) ratios were determined by designating regions of interest for the nucleus and the cytoplasm using the images taken from the DAPI and HCS CellMask channels, respectively. The intensity of the GFP staining for each of these regions was then determined from the 488 channel. The intensity indicates the relative amount of the GFP-protein fusion that is localized to either cellular compartment. The ratio of the nuclear intensity of GFP to the cytoplasmic intensity of GFP was taken to represent the extent of nuclear localization. A minimum of 30 cells were analyzed in this manner for each U2OS cell line expressing TdT, TdT(K13S,K14S), pol μ, pol μ(K4S,R5S), pol λ, pol λ(K12S,R13S), and pol λ(K12S,R13S, K27S, and R30N). N/C values of all imaged cells for each construct were averaged to determine a mean value. Values that were 2 standard deviations above or below the mean value were determined to be outliers and were eliminated. The data were analyzed by means of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s posthoc test.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Joel Andrews, University of South Alabama Mitchell Cancer Institute, for providing us with the U2OS cells, to Dr. Samuel Wilson (NIEHS) and Dr. Dale Ramsden, for providing other materials used in these studies, to Dr. R. Scott Williams for allowing us the use of the POLARstar Omega fluorescence microplate reader, and to Dr. Geoffrey Mueller for assistance with NLS software.

FOOTNOTES/Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, project number ZIA ES050111 to REL and start-up funding from the University of South Alabama to NRG. Funding for open access charge: Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [project number ZIA ES050111].

The abbreviations used are:

- FUS

fused in sarcoma

- Impα

Importin α

- Lig4

DNA ligase 4

- Impα

Importin α

- ImpαΔIBB

Importin α with deletion of the Importin β binding domain

- NHEJ

non-homologous end joining

- NLS

nuclear localization signal; NUP50, Nucleoporin 50kDa

- NUP50

Nucleoporin 50kDa

- pol β

DNA polymerase β

- pol λ

DNA polymerase λ

- pol μ

DNA polymerase μ

- TdT

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase

- TPX2

target protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2

- XRCC1

X-ray cross-complementing group 1 protein

- XRCC4

X-ray cross-complementing group 4 protein

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

REL, NRG, and TWK designed the study and wrote the paper. SAG and LCP crystallized ImpαΔIBB along with NLS peptides and determined the X-ray structures. TWK performed and analyzed peptide binding experiments. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ramadan K, Shevelev I, Hubscher U. The DNA-polymerase-X family: controllers of DNA quality? Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology. 2004;5(12):1038–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon AF, Garcia-Diaz M, Batra VK, et al. The X family portrait: structural insights into biological functions of X family polymerases. DNA Repair (Amst). 2007;6(12):1709–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uchiyama Y, Takeuchi R, Kodera H, Sakaguchi K. Distribution and roles of X-family DNA polymerases in eukaryotes. Biochimie. 2009;91(2):165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamtich J, Sweasy JB. DNA polymerase family X: function, structure, and cellular roles. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804(5):1136–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosugi S, Hasebe M, Matsumura N, et al. Six classes of nuclear localization signals specific to different binding grooves of importin α. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(1):478–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakai K, Horton P. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24(1):34–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen Ba AN, Pogoutse A, Provart N, Moses AM. NLStradamus: a simple Hidden Markov Model for nuclear localization signal prediction. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2009;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin JR, Hu J. SeqNLS: nuclear localization signal prediction based on frequent pattern mining and linear motif scoring. PloS one. 2013;8(10):e76864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernhofer M, Goldberg T, Wolf S, et al. NLSdb-major update for database of nuclear localization signals and nuclear export signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D503–D508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christie M, Chang CW, Rona G, et al. Structural Biology and Regulation of Protein Import into the Nucleus. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(10 Pt A):2060–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lange A, Mills RE, Lange CJ, Stewart M, Devine SE, Corbett AH. Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin α. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5101–5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen MJ, King CR, Dikeakos JD, Mymryk JS. Functional analysis of the C-terminal region of human adenovirus E1A reveals a misidentified nuclear localization signal. Virology. 2014;468:238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby TW, Gassman NR, Smith CE, et al. Nuclear Localization of the DNA Repair Scaffold XRCC1: Uncovering the Functional Role of a Bipartite NLS. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giesecke A, Stewart M. Novel binding of the mitotic regulator TPX2 (target protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2) to importin-α. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(23):17628–17635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung MC, Link W. Protein localization in disease and therapy. Journal of Cell Science. 2011;124(20):3381–3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knudsen NO, Andersen SD, Lutzen A, Nielsen FC, Rasmussen LJ. Nuclear translocation contributes to regulation of DNA excision repair activities. DNA Repair (Amst). 2009;8(6):682–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLane LM, Corbett AH. Nuclear localization signals and human disease. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(7):697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girard PM, Kysela B, Harer CJ, Doherty AJ, Jeggo PA. Analysis of DNA ligase IV mutations found in LIG4 syndrome patients: the impact of two linked polymorphisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(20):2369–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Divisato G, Formicola D, Esposito T, et al. ZNF687 Mutations in Severe Paget Disease of Bone Associated with Giant Cell Tumor. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(2):275–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dormann D, Rodde R, Edbauer D, et al. ALS-associated fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations disrupt Transportin-mediated nuclear import. Embo Journal. 2010;29(16):2841–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu Y, Chi BK, Xia W, et al. U1 snRNP is mislocalized in ALS patient fibroblasts bearing NLS mutations in FUS and is required for motor neuron outgrowth in zebrafish. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(6):3208–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opletalova K, Bourillon A, Yang W, et al. Correlation of Phenotype/Genotype in a Cohort of 23 Xeroderma Pigmentosum-Variant Patients Reveals 12 New Disease-Causing Polη Mutations. Human Mutation. 2014;35(1):117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kannouche P, Broughton BC, Volker M, Hanaoka F, Mullenders LHF, Lehmann AR. Domain structure, localization, and function of DNA polymerase η, defective in xeroderma pigmentosum variant cells. Genes & Development. 2001;15(2):158–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirby TW, Gassman NR, Smith CE, et al. DNA polymerase β contains a functional nuclear localization signal at its N-terminus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(4):1958–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dominguez O, Ruiz JF, de Lera TL, et al. DNA polymerase μ (Pol μ), homologous to TdT, could act as a DNA mutator in eukaryotic cells. Embo Journal. 2000;19(7):1731–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peterson RC, Cheung LC, Mattaliano RJ, White ST, Chang LMS, Bollum FJ. Expression of Human Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase in Escherichia-Coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260(19):495–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimazaki N, Yoshida K, Kobayashi T, Toji S, Tamai K, Koiwai O. Over-expression of human DNA polymerase λ in E-coli and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Genes to Cells. 2002;7(7):639–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson AA, Taggart DJ, Suo Z. Noncatalytic, N-terminal Domains of DNA Polymerase λ Affect Its Cellular Localization and DNA Damage Response. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30(5):1240–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takakusagi K, Takakusagi Y, Ohta K, Aoki S, Sugawara F, Sakaguchi K. A sulfoglycolipid β-sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol (β SQDG) binds to Met1-Arg95 region of murine DNA polymerase λ (Mmpol λ) and inhibits its nuclear transit. Protein Engineering Design & Selection. 2010;23(2):51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehdi AM, Sehgal MS, Kobe B, Bailey TL, Boden M. A probabilistic model of nuclear import of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(9):1239–1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Delaforge E, Milles S, Bouvignies G, et al. Large-Scale Conformational Dynamics Control H5N1 Influenza Polymerase PB2 Binding to Importin α. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(48):15122–15134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mueller GA, Moon AF, DeRose EF, et al. A comparison of BRCT domains involved in nonhomologous end-joining: Introducing the solution structure of the BRCT domain of polymerase λ DNA Repair. 2008; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirano H, Matsuura Y. Sensing actin dynamics: structural basis for G-actin-sensitive nuclear import of MAL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414(2):373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melen K, Fagerlund R, Franke J, Kohler M, Kinnunen L, Julkunen I. Importin α nuclear localization signal binding sites for STAT1, STAT2, and influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(30):28193–28200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conti E, Uy M, Leighton L, Blobel G, Kuriyan J. Crystallographic analysis of the recognition of a nuclear localization signal by the nuclear import factor karyopherin α. Cell. 1998;94(2):193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pang X, Zhou H-X. Design Rules for Selective Binding of Nuclear Localization Signals to Minor Site of Importin α. PLoS One. 2014;9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fontes MR, Teh T, Kobe B. Structural basis of recognition of monopartite and bipartite nuclear localization sequences by mammalian importin-α. J Mol Biol. 2000;297(5):1183–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fontes MR, Teh T, Toth G, et al. Role of flanking sequences and phosphorylation in the recognition of the simian-virus-40 large T-antigen nuclear localization sequences by importin-α. Biochem J. 2003;375(Pt 2):339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao Q, Zhang F, Nacev BA, Liu JO, Pei D. Protein N-terminal processing: substrate specificity of Escherichia coli and human methionine aminopeptidases. Biochemistry. 2010;49(26):5588–5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang R, Brattain MG. The maximal size of protein to diffuse through the nuclear pore is larger than 60 kDa. FEBS Letters. 2007;581(17):3164–3170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahajan KN, Nick McElhinny SA, Mitchell BS, Ramsden DA. Association of DNA polymerase μ (pol μ) with Ku and ligase IV: role for pol μ in end-joining double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(14):5194–5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Derose EF, Clarkson MW, Gilmore SA, et al. Solution structure of polymerase μ’s BRCT domain reveals an element essential for its role in nonhomologous end joining. Biochemistry. 2007;46(43):12100–12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Repasky JA, Corbett E, Boboila C, Schatz DG. Mutational analysis of terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated N-nucleotide addition in V(D)J recombination. J Immunol. 2004;172(9):5478–5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bentolila LA, Dandon MF, Nguyen QT, Martinez O, Rougeon F, Doyen N. The 2 Isoforms of Mouse Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase Differ in Both the Ability to Add N-Regions and Subcellular-Localization. Embo Journal. 1995;14(17):4221–4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boule JB, Rougeon F, Papanicolaou C. Comparison of the two murine terminal deoxynucleo- tidyltransferase isoforms. A 20-amino acid insertion in the highly conserved carboxyl-terminal region modifies the thermosensitivity but not the catalytic activity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(42):33184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doyen N, Boule JB, Rougeon F, Papanicolaou C. Evidence that the long murine terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase isoform plays no role in the control of V(D)J junctional diversity. J Immunol. 2004;172(11):6764–6767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parsons JL, Dianova II, Finch D, et al. XRCC1 phosphorylation by CK2 is required for its stability and efficient DNA repair. DNA Repair. 2010;9(7):835–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wirthmueller L, Roth C, Banfield MJ, Wiermer M. Hop-on hop-off: importin-α-guided tours to the nucleus in innate immune signaling. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cutress ML, Whitaker HC, Mills IG, Stewart M, Neal DE. Structural basis for the nuclear import of the human androgen receptor. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 7):957–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barros AC, Takeda AA, Dreyer TR, Velazquez-Campoy A, Kobe B, Fontes MR. Structural and Calorimetric Studies Demonstrate that Xeroderma Pigmentosum Type G (XPG) Can Be Imported to the Nucleus by a Classical Nuclear Import Pathway via a Monopartite NLS Sequence. J Mol Biol. 2016;428(10 Pt A):2120–2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lott K, Bhardwaj A, Sims PJ, Cingolani G. A minimal nuclear localization signal (NLS) in human phospholipid scramblase 4 that binds only the minor NLS-binding site of importin α1. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(32):28160–28169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ge Q, Nakagawa T, Wynn RM, Chook YM, Miller BC, Uyeda K. Importin-α protein binding to a nuclear localization signal of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP). J Biol Chem. 2011;286(32):28119–28127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chelsky D, Ralph R, Jonak G. Sequence requirements for synthetic peptide-mediated translocation to the nucleus. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9(6):2487–2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen MH, Ben-Efraim I, Mitrousis G, Walker-Kopp N, Sims PJ, Cingolani G. Phospholipid scramblase 1 contains a nonclassical nuclear localization signal with unique binding site in importin α. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(11):10599–10606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng W, Wang R, Liu X, et al. Structural insights into the nuclear import of the histone acetyltransferase males-absent-on-the-first by importin α1. Traffic. 2018;19(1):19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsuura Y, Stewart M. Nup50/Npap60 function in nuclear protein import complex disassembly and importin recycling. Embo Journal. 2005;24(21):3681–3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Braithwaite EK, Kedar PS, Stumpo DJ, et al. DNA Polymerases β and λ Mediate Overlapping and Independent Roles in Base Excision Repair in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts. Plos One. 2010;5(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crespan E, Furrer A, Rosinger M, et al. Impact of ribonucleotide incorporation by DNA polymerases β and λ on oxidative base excision repair. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cuneo MJ, London RE. Oxidation state of the XRCC1 N-terminal domain regulates DNA polymerase β binding affinity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(15):6805–6810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma YM, Lu HH, Tippin B, et al. A biochemically defined system for mammalian nonhomologous DNA end joining. Molecular Cell. 2004;16(5):701–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fang QM, Inanc B, Schamus S, et al. HSP90 regulates DNA repair via the interaction between XRCC1 and DNA polymerase β. Nature Communications. 2014;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Macromolecular Crystallography, Pt A. 1997;276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mccoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallographica Section D: Biological Crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2004;60:2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu W, Xie J, Chau HW, Si BC. Evaluation of parameter uncertainties in nonlinear regression using Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet. Environmental Systems Research. 2015;4(1):4. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edelhoch H Spectroscopic determination of tryptophan and tyrosine in proteins. Biochemistry. 1967;6(7):1948–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.