Abstract

We report a 12-week-old boy presenting with incomplete refractory Kawasaki disease (KD) complicated with macrophage activation syndrome (MAS). The infant presented with cerebral irritability, pain, tachypnoea and vomiting for 10 days. He did not fulfil any of the classic diagnostic criteria for KD. Pericardial effusion on echocardiography in addition to severe dilatation of the coronary arteries in combination with leucocytosis and raised acute phase reactants led to the diagnosis of incomplete KD. Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin and aspirin was initiated but without any response. The condition was subsequently refractory to additional treatment with infliximab and high-dose methylprednisolone. His condition worsened, fulfilling the criteria for MAS. High-dose anakinra was initiated, and remission of the inflammation was achieved.

Keywords: paediatrics (drugs and medicines), vasculitis

Background

Macrophage-activating syndrome (MAS) is a rare and potential life-threatening complication of rheumatic disease, most often seen in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) but also described in systemic lupus erythematosus and Kawasaki disease (KD).

Kawasaki disease is an acute vasculitis of unknown aetiology that predominantly affects children under 5 years. Coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) is a well-described complication to KD and the leading course of acquired heart disease in children.1 Infants <6 months with KD, rarely meet the classic diagnostic criteria of KD and are therefore often diagnosed late in the course of the disease.2 They are classified as having incomplete KD.1 The frequency of cardiac complications including CAA, in patients younger than 6 months, is significantly higher compared with the risk in older children.2 3 Incomplete KD can mimic viral or septic illness and can present with irritability, gastrointestinal symptoms, unexplained aseptic meningitis, sterile pyuria and reactivation of Bacille de Calmette-Guérin vaccine spot among other non-classic symptoms.1 3 In a study of 120 children <6 months with KD, Chang revealed that the rate of incomplete KD was 35%,2emphasising the importance of a high index of suspicion of this entity in infants. Recommended first-line treatment for KD is high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in combination with aspirin reducing the risk of developing CAA from 15%–25% to 5%–7%.1 Children not responding to first-line treatment (10%–20%) are referred to as having refractory KD. They have a high risk of developing CAA.1

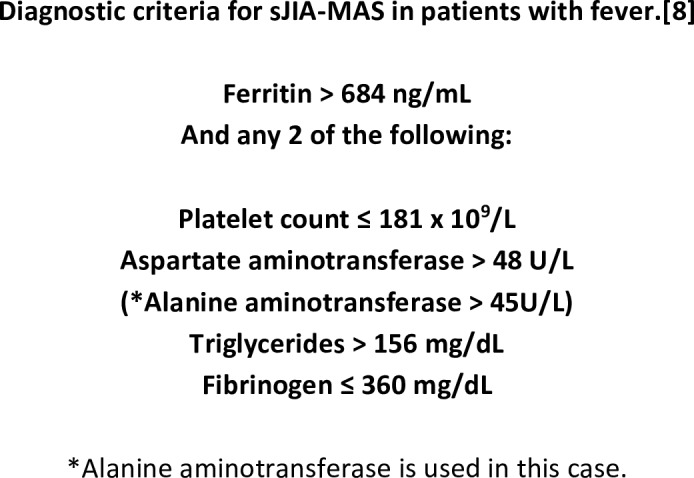

MAS is currently classified among the secondary or acquired forms of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH). Primary HLH (pHLH) is an autosomal recessive disorder with gene defects in one of the HLH loci.4 Secondary HLH (sHLH) is primarily triggered by infections, malignancies or rheumatic disorders. Clinical MAS is characterised by high fever, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and arthritis. Involvement of the central nervous system, heart, lungs and kidneys and may consequently lead to multiple organ failure.5 Laboratory findings are increased serum ferritin, cytopaenias and liver involvement (figure 1). The pathogenesis of MAS is defined by increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-18, tumour necrosis factor alpha and interferon gamma, expansion of T lymphocytes and haemophagocytic macrophages.6 Several proposals for diagnostic criteria for HLH exist, trying to identify the condition as soon as possible to avoid severe complications. The HLH 2004 protocol7 and sJIA-MAS classification8 are used as guidelines for diagnosis and treatment but have not been evaluated in relation to MAS in KD. Studies comparing the diagnostic approaches of HLH and sJIA-MAS have revealed that the sJIA-MAS classification has the highest sensitivity in patients with MAS as a complication of rheumatic disease.8 Similarities between the laboratory findings in KD and MAS are well known, and this increases the risk of overlooking MAS.1 8

Figure 1.

Diagnostic criteria for macrophage activation syndrome. sJIA-MAS, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis macrophage-activating syndrome.

No established international consensus exits on how to treat KD-MAS. We report a case of incomplete refractory KD complicated with MAS successfully treated with high-dose anakinra.

Case presentation

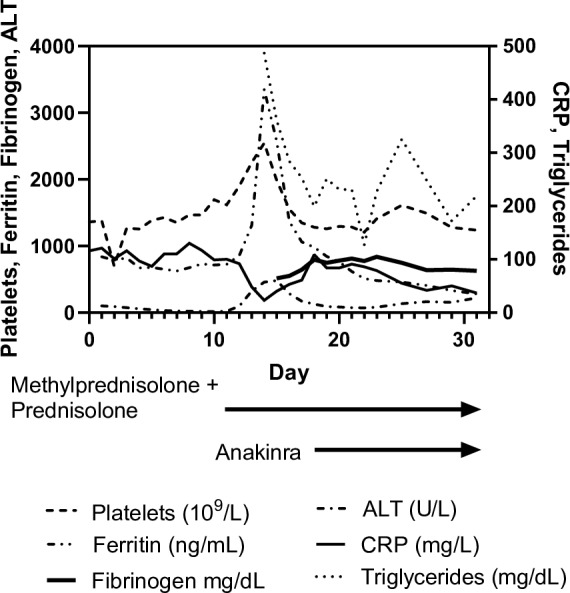

A 12-week-old Caucasian boy was admitted to the paediatric emergency department with a history of 10 days of vomiting, continuous crying and irritability. There was no rash, conjunctivitis, oral changes, peripheral oedema, signs of arthritis or cervical lymphadenopathy neither at admission nor in the history. The parents had no suspicion of fever in the child before admission. After admission, the body temperature was monitored every 6 hours, to rule out sJIA, and never exceeded 37.5°C. He was the third child in the family with no history of inherited diseases, and the neonatal period had been uncomplicated. At admission, he was irritable and responded poorly. Initial laboratory studies showed elevated acute phase reactants (figure 2). Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) revealed leucocytosis of mononuclear dominance, normal glucose and protein levels. Antibiotic and antiviral treatment was initiated for both suspected sepsis and viral encephalitis.

Figure 2.

Acute phase reactants. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CRP, C reactive protein.

Within the following 12 hours, his clinical condition deteriorated. He developed respiratory distress and chest radiography was suspicious for apical pneumonia and enlargement of the heart. Echocardiography showed pericardial effusion and severe dilatation of the left anterior descending (4.2 mm; Z-score 12.68) and right coronary artery (4.2 mm; Z-score 9.3). Atypical KD was diagnosed and the patient was started on IVIG (2 g/kg) and aspirin (100 mg/kg) resulting in a short temporary improvement of his clinical condition and biochemical markers (figure 2, day 2). The following days there was an increased activation of the immune system with rising C reactive protein (CRP), platelet count and leucocytes. His general appearance worsened and despite supplementary nutrition, he lost weight. Refractory KD was suspected. Infliximab (5 mg/kg) was administered on day 3. As the inflammatory markers kept rising, a second dose of IVIG (2 g/kg) was administered on day 7. Echocardiography showed no reduction of pericardial effusion and coronary artery dilatation remained stationary. A 3-day course of high-dose methylprednisolone (dose reduction to 15 mg/kg/day due to hypertension) was initiated at day 12 but only administered for two consecutive days because of adverse effects. Methylprednisolone was followed by oral prednisolone (2 mg/kg/day). Simultaneously elevated platelets (2544×109/L) and leucocytosis (50×109/L) was interpreted as a consequence of steroid treatment. At day 15 (figure 2), he developed remarkably hyperferritinaemia (3349 ng/mL). A subsequent elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (457 U/L) and triglyceride (487 mg/dL) in combination with a rapid fall in CRP made concerns about MAS/HLH present. Bone marrow aspiration was obtained, showing few haemophagocytic cells. The inflammatory response was massive and multiple organ systems affected why empirical treatment with anakinra (5 μg/kg/day) was administered on day 18. As no improvement in his clinical condition was seen, the dose of anakinra was increased (10 µg/kg/day) on day 19. Shortly after, his clinical appearance improved and during the next weeks, he slowly recovered and the inflammatory markers normalised.

He was discharged from the hospital on day 53, continuing daily aspirin. Oral prednisolone and subcutaneous anakinra were tapered totally over the next 6 months.

Investigations

At admittance, a complete blood count revealed elevated platelets (1360×109/L), leucocytosis (35.2×109/L), neutrophils (20×109/L), low haemoglobin (95 g/L) and high ferritin (837 ng/mL), increased CRP (116 mg/L) and ALT (101 U/L) all compatible with KD (figure 2). The patient had serositis involving the urinary tract (urine sample showed aseptic pyuria), meninges (CSF revealed leucocytosis of mononuclear dominance, normal glucose and proteins) and pericardium (pericardial effusion). No confirmed presence of bacteria or viruses in CSF, urine, tracheal secretion or blood was found.

Ultrasound of the abdomen revealed hepatomegaly.

Immune defect investigation was conducted. Flow-cytometry revealed marked neutrophilia (22.1×109/L; normal (in house) range: 5.5–17.0×109/L, monocytosis (2.9×109/L; 0.3–1.2×109/L), CD19+ B (2.2×109/L; 0.3–1.0×109/L), CD4+ T (7.8×109/L; 0.9–4.1×109/L) and CD8+ T (1.7×109/L; 0.9–4.1×109/L) cell lymphocytosis with normal T cell subset distributions. Increased T-cell activation (HLA-DR expression: 2%) was not observed. The patient had normal natural killer cell concentrations (0.5×109/L; 0.1–1.1×109/L). The neutrophil oxidative response was normal as indicated by a normal dihydrorhodamine flow cytometric test, thereby precluding chronic granulomatous disease as a cause for HLH.

Genetic workup revealed no mutations in genes associated with pHLH (PRF1, UNC13D, Syntaxin 11). Also next-generation sequencing, using a custom-made in-house Ion AmpliSeq panel (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA) which targeted 276 primary immunodeficiency genes, revealed no clinically significant genetic variations in genes also implicated in HLH such as SH2DIA (100% coverage, encodes X-linked SLAM-Associated Protein), BIRC4 (99% coverage, encodes X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis (XIAP)) as well as three autosomal genes: LYST (96% coverage, encodes lysosomal trafficking regulator), RAB27A (94% coverage, encodes the Rab27a protein) and STXBP2 (92% coverage, encodes the syntaxin binding protein 2). It did reveal that the patient was hemizygous for a CD40LG variant reported to cause recurrent viral and bacterial infections, hypogammaglobulinaemia and Epstein-Barr virus-driven lymphoproliferation when cosegregated with a hypomorphic hemizygous mutation in XIAP.9

The IgG, IgM and IgA levels were within the normal range.

Outcome and follow-up

At the point of this report, the patient is 19 months old. No relapse was seen, and he does not suffer from infectious diseases more frequently than children of the same age. His physical and mental development is normal. Inflammatory markers normalised 6–7 weeks after initiating treatment with anakinra, apart from platelets, which were above the normal range for 3 months. No progression in coronary artery dilatation was seen during the disease course but no improvement either.

Discussion

The outcome of MAS can be fatal, and it is therefore of great importance to diagnose and start treatment as early as possible. This case illustrates the difficulties in both diagnosing incomplete KD and subsequently MAS in an infant.

Late diagnosis and treatment are prognostic for the development of cardiac complications in KD,1 10 emphasising the already accepted knowledge that treatment of KD should not always await the fulfilment of the classic criteria when systemic inflammation is ongoing. This case emphasizes the importance of introducing echocardiography as an early examination in an atypical presentation of systemic inflammatory illness in infants, as detection of coronary artery dilatation helps diagnosing KD. Coronary dilatation and pleural effusion are also seen in sJIA. Our patient did not present with arthritis or fever at any time and sJIA, therefore, did not seem to be the most obvious cause of the clinical picture. Coronary dilatation is much more commonly seen in KD than in sJIA,11 12 especially severe coronary artery abnormalities as seen in our patient.

Diagnostic criteria and treatment recommendations for KD-MAS are non-existing. The available recommendations about MAS builds on data from sJIA-MAS.

Wang et al concluded that MAS may frequently be an under-recognised complication of KD due to lack of sufficient diagnostic criteria.13 This point of view is supported by Choi et al who raise the question: ‘Should refractory Kawasaki disease be considered occult macrophage activation syndrome?’.14 It puts the clinicians in a diagnostic challenge as early recognition, and treatment of MAS is of great importance. When untreated, MAS has a mortality rate of 8% in children with sJIA-MAS.5 The current clinical criteria for sJIA-MAS,8 or HLH,7 are not validated in KD-MAS.

In this case, the sJIA-MAS criteria were used to make the diagnosis. The patient did fulfil the criteria (figures 1 and 2) for sJIA-MAS except for the presence of fever. In the 2016 sJIA-MAS guidelines, Ravelli et al outline that the sJIA-MAS classification criteria do not capture all instances of MAS and particularly not those with an incomplete clinical presentation.8

The patient had elevated ferritin and ALT, in this case considered equivalent to aspartate aminotransferase used in the 2016 classification criteria for MAS in sJIA.8 Ferritin is a biochemical marker with high sensitivity in detecting early development of MAS.15 Triglycerides were elevated (487 mg/dL). Fibrinogen was not below its normal range as expected in MAS. In this case fibrinogen behaved as an acute phase protein. Platelet count did not show low values as seen in sJIA-MAS but was high as seen in KD.1

Regardless of the diagnostic approach, the main goal in the clinical setting was to obtain control of the inflammatory response as fast as possible. Based on the clinical and biochemical findings, we found it most likely that the patient had MAS triggered by KD. This case underlines the major challenges in both diagnosing and treating inflammatory diseases in infants. Due to the critical condition of the patient and the fact that several anti-inflammatory drugs were administered already, alternative anti-inflammatory treatment was needed to avoid fatal development. High-dose methylprednisolone had been administered just before the rise in ferritin and ALT. The patient was refractory to the first dose of IVIG, why secondary treatment with infliximab and later methylprednisolone was introduced. At present time, there is no general consensus on how to align the management of refractory KD.

In this case anakinra was chosen as the best possible treatment, based on multiple case reports revealing the effect of anakinra in refractory KD16–20 and the recommendation from The American Heart Association in refractory KD.1 In addition, the successful use of anakinra as treatment for both KD-MAS,20 21 and sJIA-MAS,8 is reported, suggesting that IL-1 most likely plays a key role in the inflammatory response. An IL-1 blocking agent was chosen in hope of achievement of fast disease control.

There has been an increased focus on IL-1 as a central mediator in systemic inflammation. Lee et al made studies in mouse models, strongly indicating that both IL-1α and IL-1β play a central role in KD and in the development of CAA. They demonstrated that an IL-1 antagonist could block this pathway successfully.22

In the present case, the patient improved clinically within a few days after initiating treatment with anakinra and a rapid fall in ferritin and ALT was observed. Whether the improvement was an effect of anakinra or steroid or a combination of both remains uncertain.

Clinical trials with the purpose of investigating treatment with IL-1 antagonist in relation to KD are currently initiated.23 In addition, international initiatives are taking place with the purpose of making guidelines for diagnosing and treating MAS not only related to sJIA. Hopefully they will provide new important knowledge for future treatment of both KD and KD-MAS. We accentuate the need for international clinical guidelines for the diagnosis of KD-MAS. Meanwhile, we recommend the use of the sJIA-MAS guideline.8

Learning points.

Development of macrophage-activating syndrome (MAS) should be considered early in the management of children with refractory Kawasaki disease (KD).

Diagnostic criteria for MAS triggered by KD are non-existing, and in the meanwhile, we recommend the systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis MAS criteria to be used.

Treatment of refractory KD and MAS with IL-1 antagonist should be taken into consideration.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML-H has been in charge of the writing process of this case report and made changes to the manuscript. She has made the figure regarding the laboratory findings and MAS criteria and the submission and resubmission. UBH supported with the information on genetic and immune deficiency investigation and contributed with grammar correction. AEC has been supportive with knowledge of expert level and supported with input on the focus of this case report. She was responsible for the correction of language and grammar.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

References

- 1. McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Long-Term Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement for Health Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e927–e999. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chang F-Y. Characteristics of KD in infants younger than 6 month. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2006;25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yoon YM, Yun HW, Kim SH. Clinical Characteristics of Kawasaki Disease in Infants Younger than Six Months: A Single-Center Study. Korean Circ J 2016;46:550–5. 10.4070/kcj.2016.46.4.550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2009;1:127-31 10.1182/asheducation-2009.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minoia F, Davì S, Horne A, et al. Clinical features, treatment, and outcome of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multinational, multicenter study of 362 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014;66:3160–9. 10.1002/art.38802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schulert GS, Grom AA. Pathogenesis of macrophage activation syndrome and potential for cytokine- directed therapies. Annu Rev Med 2015;66:145–59. 10.1146/annurev-med-061813-012806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. 10.1002/pbc.21039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davì S, et al. 2016 Classification Criteria for Macrophage Activation Syndrome Complicating Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:481–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rigaud S, Lopez-Granados E, Sibéril S, et al. Human X-linked variable immunodeficiency caused by a hypomorphic mutation in XIAP in association with a rare polymorphism in CD40LG. Blood 2011;118:252–61. 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salgado AP, Ashouri N, Berry EK, et al. High Risk of Coronary Artery Aneurysms in Infants Younger than 6 Months of Age with Kawasaki Disease. J Pediatr 2017;185:112–6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar S, Vaidyanathan B, Gayathri S, et al. Systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis with macrophage activation syndrome misdiagnosed as Kawasaki disease: case report and literature review. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:1065–9. 10.1007/s00296-010-1650-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Binstadt BA, Levine JC, Nigrovic PA, et al. Coronary artery dilation among patients presenting with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatrics 2005;116:e89–e93. 10.1542/peds.2004-2190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang W, Gong F, Zhu W, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in Kawasaki disease: more common than we thought? Semin Arthritis Rheum 2015;44:405–10. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi UY, Han SB, Lee SY, et al. Should refractory Kawasaki disease be considered occult macrophage activation syndrome? Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;46:e17 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ravelli A, Davì S, Minoia F, et al. Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2015;29:927–41. 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sánchez-Manubens J, Gelman A, Franch N, et al. A child with resistant Kawasaki disease successfully treated with anakinra: a case report. BMC Pediatr 2017;17:102 10.1186/s12887-017-0852-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kone-Paut I, Cimaz R, Herberg J, et al. The use of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) in Kawasaki disease: A retrospective cases series. Autoimmun Rev 2018;17:768–74. 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dusser P, Koné-Paut I. IL-1 Inhibition May Have an Important Role in Treating Refractory Kawasaki Disease. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:163 10.3389/fphar.2017.00163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen S, Tacke CE, Straver B, et al. A child with severe relapsing Kawasaki disease rescued by IL-1 receptor blockade and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:2059–61. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shafferman A, Birmingham JD, Cron RQ. High dose Anakinra for treatment of severe neonatal Kawasaki disease: a case report. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2014;12:26 10.1186/1546-0096-12-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miettunen PM, Narendran A, Jayanthan A, et al. Successful treatment of severe paediatric rheumatic disease-associated macrophage activation syndrome with interleukin-1 inhibition following conventional immunosuppressive therapy: case series with 12 patients. Rheumatology 2011;50:417–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee Y, Schulte DJ, Shimada K, et al. Interleukin-1β is crucial for the induction of coronary artery inflammation in a mouse model of Kawasaki disease. Circulation 2012;125:1542–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.072769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burns JC, Koné-Paut I, Kuijpers T, et al. Review: Found in Translation: International Initiatives Pursuing Interleukin-1 Blockade for Treatment of Acute Kawasaki Disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017;69:268–76. 10.1002/art.39975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]