Abstract

Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A), biosynthesized by activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) 2, was initially identified as a potent endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor in perfused rat kidney. Subsequently, the effect of Up4A on vascular tone regulation was intensively investigated in arteries isolated from different vascular beds in rodents including rat pulmonary arteries, aortas, mesenteric and renal arteries as well as mouse aortas, in which Up4A produces vascular contraction. In contrast, Up4A produces vascular relaxation in porcine coronary small arteries and rat aortas. Intravenous infusion of Up4A into conscious rats or mice decreases blood pressure, and intravenous bolus injection of Up4A into anesthetized mice increases coronary blood flow, indicating an overall vasodilator influence in vivo. Although Up4A is the first dinucleotide described that contains both purine and pyrimidine moieties, its cardiovascular effects are exerted mainly through activation of purinergic receptors. These effects not only encompass regulation of vascular tone, but also endothelial angiogenesis, smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and vascular calcification. Furthermore, this review discusses a potential role for Up4A in cardiovascular pathophysiology, as plasma levels of Up4A are elevated in juvenile hypertensive patients and Up4A-mediated vascular purinergic signaling changes in cardiovascular disease such as hypertension, diabetes, atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Better understanding the vascular effect of the novel dinucleotide Up4A and the purinergic signaling mechanisms mediating its effects will enhance its potential as target for treatment of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Up4A, purinergic receptor, vascular function, cardiovascular disease

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Increasing evidence suggests that extracellular nucleotides contribute to cardiovascular homeostasis [1-3]. Nucleotides, such as ATP, UTP, and nucleosides such as adenosine, can be released from adventitial nerves or from platelets, erythrocytes and endothelial cells and interact with purinergic receptors to regulate vascular tone, endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and migration, vascular permeability, inflammation and angiogenesis. In addition to mononucleotides, dinucleotides exist [4, 5]. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A) contains both a purine and a pyrimidine part, and was the first dinucleotide of this kind identified in living organisms [6]. Up4A is biosynthesized by activation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) 2 [6, 7]. Up4A synthesis by the endothelium is enhanced by stimulation with ATP, UTP, acetylcholine (ACh), endothelin-1 (ET-1), the calcium ionophore (A23187) as well as by mechanical stress [6]. The plasma concentrations of Up4A detected in healthy subjects (~4 nM) are in the vasoactive range suggesting that Up4A contributes to the regulation of vascular tone [6]. Indeed, Up4A was initially identified as a potent endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor in isolated perfused rat kidneys [6]. Similar vasoconstrictor effects were subsequently found in several other rodent vascular beds including rat pulmonary arteries, aortas, mesenteric and renal arteries as well as in isolated mouse aortas and hearts [6, 8-10]. Notably, the plasma level of Up4A is elevated (~33 nM) in juvenile hypertensive patients and intra-aortic bolus injection of Up4A increases mean arterial pressure in rats in vivo suggesting a potential role for Up4A in the pathogenesis of hypertension and possibly other cardiovascular diseases [6, 11].

Interestingly, more recent investigations of its vascular effects have shown Up4A to produce potent relaxation of porcine coronary small arteries [12], to increase coronary blood flow in anesthetized mice [10] and to induce hypotension in conscious rats and mice [13]. Moreover, Up4A was recently shown to stimulate tubule formation in a 3D co-culture system, reflecting its angiogenetic potential [14], to promote VSMC proliferation [15] and migration [16] and vascular calcification [17]. Finally, recent studies have explored the alteration in the vascular responses to Up4A in disease conditions, such as hypertension [18-21], diabetes [22-24], atherosclerosis [10] and myocardial infarction [12]. This review will provide an overview of the vascular effects of Up4A, its signaling and alterations therein in cardiovascular disease.

2. Biosynthesis and degradation of Up4A

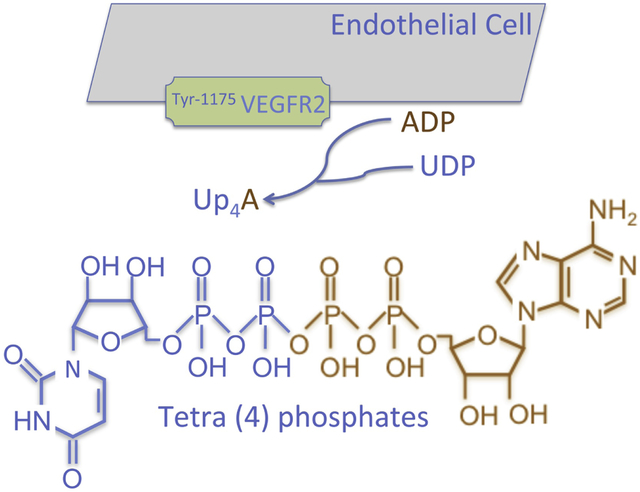

Up4A was identified in human endothelial cells by Jankowski et al. more than a decade ago [6]. Up4A was subsequently shown by the same group of investigators to be biosynthesized by VEGFR2 [7]. Human dermal endothelial cells generate increasing concentrations of Up4A when incubated with ADP and UDP. The responsible enzyme was isolated by chromatography and mass spectrometric analysis revealed that the enzymatic activity was specifically caused by VEGFR2, as no Up4A was detected after incubation of ADP and UDP with VEGFR1 or VEGFR3 [7]. Several functional domains are shared within VEGFR1, 2, and 3. However, the unique domain of Tyr-1175 of VEGFR2 is most likely essential for the enzymatic activity mediating Up4A synthesis [7] (Fig. 1). Further proof on the key role of VEGFR2 in synthesis of Up4A was provided by VEGFR2-transfection into the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293T/17, which could then synthesize Up4A in vitro [7]. Up4A subsequently facilitates VEGFR2-mediated pathways such as p42/44 MAP kinase (ERK1/2) phosphorylation [7], suggesting that Up4A could amplify the proliferative or angiogenic response to VEGF. Given that VEGFR2 is primarily expressed in endothelial cells, the biosynthesis of Up4A may play a crucial role in cardiovascular homeostasis.

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of Up4A is biosynthesized by activation of VEGFR2 (particularly via domain of Tyr-1175) in endothelial cells with substrates of ADP and UDP. Up4A is the first dinucleotide containing both purine and pyrimidine moieties and exerts its biological influence in vascular system mainly through activation of purinergic receptors.

In addition to its synthesis in endothelial cells, Up4A was found to be synthesized in renal tubular cells [25], human liver hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2, human acute monocytic leukemia cell line THP-1 and murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 [7]. As renal tubular and peritubular cells [26, 27], HepG2 [28, 29], THP-1 [30], and RAW264.7 [31] all have been shown to express VEGFR2, Up4A synthesis by these cells is likely also mediated by activation of VEGFR2. Future studies are needed to establish whether Up4A synthesis in these cells is indeed mediated by the VEGFR2, and whether other VEGFR2-expressing cells also are capable of synthesizing Up4A. This is particularly interesting with respect to erythrocytes, as these cells express VEGFR2 [32] and are regarded as a nucleotide pool releasing ATP in response to low oxygen tensions to regulate tissue perfusion [33-35].

In addition to Up4A, other dinucleotide polyphosphates have also been shown to be synthesized by activation of VEGFR2, depending on the local availability of mononucleotides. These include Ap4A, Ap3G and Gp2G which were all detected when the immobilized VEGFR2 was incubated with ADP+GMP, and Ap6A, Ap4G and Gp2G which were detected in the presence of ATP+GMP in endothelial cells [7].

Whereas activation of VEGFR2 has been shown to be responsible for the synthesis of Up4A, with a half-life of 4.5 min in plasma [36], the catabolism of Up4A remains poorly understood. Previous reports showed that dinucleotides were mainly degraded to mononucleotides by ecto-nucleotidases such as nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (NTPDase, also known as ecto-ATPDase CD39) and ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD37) [5, 37]. These ecto-nucleotidases are present on a variety of cell types, including vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells [37], epithelial cells [38], human liver cells [39, 40], lymphocytes [41], dendritic cells [42], chromaffin cells [43], rat mesangial cells [44], periodontal cells [45]. This implies that Up4A may be also degraded through those ecto-nucleotidases, and that its vascular effects may be exerted by its degradation products. However, the Up4A-induced increase in perfusion pressure in isolated kidneys was greater than that caused by UTP or ATP. Moreover, Up4A had a longer half-life than ATP [6, 25], Up4A exerted no tachyphylactic pattern in rat aortas [46] and the NTPDase inhibitor ARL67156 had no effect on Up4A-mediated potent coronary relaxation [12]. Another NTPDase, apyrase, inhibited UTP- and ATP- but not Up4A-mediated VSMC migration [16]. Altogether, these findings suggest that Up4A-mediated vascular effects are direct, and not indirect through its degradation products or inhibition of purinergic enzymes [36]. The catabolism of Up4A may be through other types of ecto-nucleotidases e.g. nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterases (NPP) and further studies are needed to explore this mechanism.

3. Purinergic receptors in the vascular system

All purine and pyrimidine mononucleotides and dinucleotides predominantly exert their biological effects through purinergic receptors. Purinergic receptors have been classified into two subtypes: P1 and P2 receptors, based on their pharmacological properties and molecular cloning [33, 47]. Four subtypes of P1 receptors (also termed adenosine receptors), all metabotropic, have been cloned, namely A1R, A2AR, A2BR and A3R. A1R and A3R are negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase through the Gi/o protein alpha-subunits and decrease cAMP levels, whereas A2AR and A2BR are positively coupled to adenylyl cyclase through Gs and enhance cAMP levels [48-50]. The P2 receptors are further classified into two major families: ionotropic P2XRs and metabotropic P2YRs [33, 51]. At least 7 P2XRs (P2X1-7R), and 8 P2YRs (P2Y1R, P2Y2R, P2Y4R, P2Y6R, P2Y11R, P2Y12R, P2Y13R and P2Y14R) have been cloned to date [52].

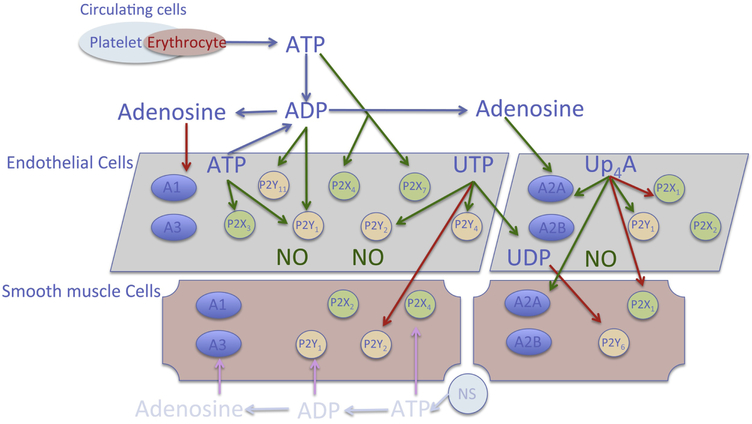

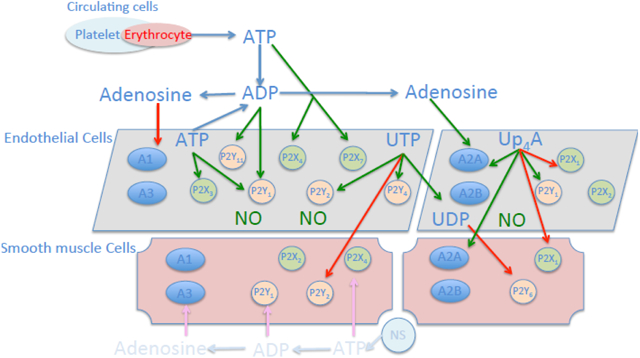

Upon stimulation by extracellular nucleo(t/s)ides (ATP, ADP, UTP, UDP and adenosine), purinergic signaling is initiated and results in various physiological responses, including platelet aggregation, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis, immune responses and vascular tone regulation [3, 33, 34, 48, 50]. Purinergic receptors are capable of mediating responses to several nucleotides and have overlapping ligand preferences. P2X1-7Rs are mainly activated by ATP; P2Y1R, P2Y12R and P2Y13R are activated by ADP, while P2Y1R are sensitive to both ATP and ADP. Moreover, P2Y2R and P2Y4R are preferably sensitive to UTP, while P2Y6R preferably responds to UDP stimulation [33] (Fig. 2). Distribution and expression of purinergic receptors are ubiquitous throughout the body, with sub-type distributions varying regionally across tissues, including brain, heart, lung, liver, vasculature, circulation, autonomic nerve terminals, as well as across species [33, 34, 48]. In the vascular system, all four P1 receptor subtypes are expressed in both endothelial and smooth muscle cells [48, 50]. With respect to regulation of vascular tone, activation of A1R and A3R typically results in vascular contraction, whereas activation of A2AR and A2BR leads to vascular relaxation [48, 50]. The P1 receptor-mediated vascular tone regulation appears to be independent of receptor subtype location [48], whereas activation of P2 receptor subtypes on endothelial cells typically leads to vasodilation, while activation of P2 receptor subtypes on smooth muscle cells results in vasoconstriction [3, 53]. Thus, activation of P2X1R, P2X2R, P2X4R, P2Y1R, P2Y2R and P2Y6R on smooth muscle cells results in vasoconstriction [3], while activation of P2X1R, P2X2R, P2X3R, P2X4R P2X7R, P2Y1R, P2Y2R, P2Y4R and P2Y11R on endothelial cells has been shown to induce the production of nitric oxide (NO) and subsequent vasodilation [3] (Fig. 2), although there are also observations to suggest that activation of P2X1R upon stimulation in endothelial cells contributes to vascular contraction [9, 54].

Figure 2.

Distribution and location of key purinergic receptors in vascular system. Nucleotides are released from different sources in circulation including endothelial cells, erythrocytes, platelets and neural system (NS). Different nucleo(s)tides activate their preferable purinergic receptors to exert vascular biological influence. In general, activation of purinergic receptors on endothelial cells results in nitric oxide (NO) production leading to vasodilation, whereas activation of purinergic receptors on smooth muscle cells leads to vasoconstriction. The dinucleotide Up4A mainly activates A2AR, P2X1R on both endothelial and smooth muscle cells, as well as P2Y1R on endothelial cells. Red arrow: contractile effect; green arrow: dilating effect.

Intriguingly, dimerization and cross-talk among purinergic receptors have been reported, which increases the diversity of purinergic signaling. For example, in the coronary microcirculation, the A1R may inhibit A2AR-dependent relaxation [55] and the A3R negatively regulates the A2AR-mediated increase in coronary flow [56]. Oligomeric association of A1R with P2Y1R has been found in HEK293 cells to generate P2Y-like adenosine receptors [57]. It has been also shown that A1R and P2Y1R are co-localized in neurons of the rat cortex, hippocampus and cerebellum [58]. In addition, P2Y6R has been found to heterodimerize with the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), e.g. angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1) to promote angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced hypertension [59].

Signaling through purinergic receptors is terminated/repressed via feedback mechanisms of desensitization (during the continued presence of ligand or receptor agonist stimulation), with the temporal and mechanistic aspects of these processes varying across purinergic receptor subtypes. The A1R appears relatively resistant to phosphorylation and slowly internalizes over hours [48, 60]. Both A2AR and A2BR desensitize within hours and similarly through G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) 2-dependent phosphorylation [48, 61], while the A3R undergoes desensitization within minutes via GRK2 phosphorylation [62]. P2X1R and P2X3R desensitization occurs in milliseconds, while the rate of desensitization of other P2XRs like P2X2R and P2X4R is 100-1,000 times slower [33]. Both P2Y1R and P2Y12R rapidly desensitize in human platelets requiring PKC and GRK2/6, respectively [63]. A unique feature of the P2Y6R is its slow desensitization and internalization with only one known potential phosphorylation site for PKC [33, 64]. For more details on purinergic receptor desensitization, the reader is referred to several excellent review articles [33, 48, 65].

As mentioned above, nucleotide-mediated purinergic signaling contributes to a number of processes involved in normal vascular function. Importantly, the vascular effects of nucleotides are influenced by the location of the release of purine/pyrimidine. In general, nucleotides released at the adventitia (e.g., ATP from sympathetic nerves) are vasocontractile, whereas their effects upon release at the intima (e.g., from erythrocytes, endothelial cells) depend on endothelial integrity, i.e. endothelium-dependent vasodilation occurs with intact endothelium, whereas contraction is induced if the endothelium is damaged [3]. The balance between nucleotide release and the activities of ecto-nucleotidases eventually determines the extracellular levels of ATP, ADP, UTP, and adenosine and consequently the prevailing target effects [33]. As all cells in the vascular system express one or more (sub)types of purinergic receptors, and significant changes in vascular purinergic signaling pathways occur in pathological conditions including hypertension, ischemic heart disease and diabetes, purinergic receptors provide potential targets for treatment of vascular disease [33, 34, 48, 66, 67]. Indeed, P2Y12R-blockers, like clopidogrel and prasugrel, are widely prescribed as platelet inhibitors in the treatment of thrombosis, stroke and myocardial infarctions in millions of patients [34, 67]. For further details on the pathophysiological role of purinergic receptors in cardiovascular disorders, the reader is referred to several excellent review articles [68-70].

4. Up4A and physiological vascular function

Up4A was initially identified as a potent vasoconstrictor [6]. Subsequent studies performed in various vascular beds revealed that Up4A not only produces vascular contraction but can also elicit vascular relaxation [8, 12]. Intra-aortic injection of Up4A into rats induces a long-lasting increase in mean arterial blood pressure [6], while intravenous infusion of Up4A into conscious rats and mice induces systemic vasodilation [13], and an intravenous bolus injection of Up4A into mice increases coronary blood flow [10]. Up4A contains both a purine and pyrimidine structure and therefore can activate both P1 and P2 receptors to launch such diverse vascular actions. As outlined below, there is a large heterogeneity of Up4A-mediated effects on vascular tone between different vascular beds and species or strains, which likely depends on local variations in purinergic receptor expression. In addition to purinergic receptors, Up4A can activate non-purinergic receptors. Thus, Up4A-induced vascular contraction in mouse aortas is partly mediated through activation of AT1 receptors in addition to P2X1R [20], suggesting a cross-talk between purinergic receptors and G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) [57, 59]. Similarly, our preliminary observations indicate that Up4A-induced relaxation in porcine coronary small arteries can be attenuated by ET-1 receptor (belonging to GPCRs) blockade (unpublished). Whether Up4A has its own unique receptor is currently unknown, and future studies exploring Up4A-induced non-purinergic signaling will yield more insights into Up4A-mediated vascular tone regulation.

4.1. Aorta

4.1.1. Rats

Linder et al. characterized the effect of Up4A in aortas isolated from Sprague Dawley rats and found that Up4A, without preconstriction, produced a concentration-dependent contraction [46]. This Up4A-mediated contraction was potentiated by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) blockade and by endothelium denudation to a similar extent, while NOS blockade failed to affect the Up4A-mediated contraction in endothelium-denuded aortic rings, suggesting NO is the main endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) that is responsible for mitigating Up4A-mediated contraction in isolated rat aortas [46]. In endothelium-denuded aortic rings, Up4A-mediated contraction was significantly attenuated by P1R inhibition with the non-selective P1R antagonist 8-(p-sulphophenyl)-theophylline (8PST) and P2XR inhibition with a high concentration (100 μM) of NF279 (IC50 of 19 nM for P2X1R, 0.76 μM for P2X2R and 1.62 μM for P2X3R) [71], respectively [46]. As for the post-receptor signaling pathways in smooth muscle cells, Up4A-mediated vascular contraction was markedly attenuated by L-type Ca2+ channel blockade with nifedipine and by Rho-kinase inhibition with Y27632. Moreover, the vasoconstrictor effect of Up4A in endothelium-denuded aortas was also decreased by reducing oxidative stress through either the superoxide anion dismutase mimetic TEMPOL or by inhibition of NADPH oxidases with apocynin [46]. These findings suggest that P1R and most likely P2X1R on VSMCs activate L-type Ca2+ channels and Rho-kinase signaling, accounting for Up4A-mediated smooth muscle contraction. This effect involves NADPH activation and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In the same study, Linder et al. observed a ~25% vasodilator action of Up4A on rat aortas when vascular tone was elevated by phenylephrine (PE) prior to administration of Up4A [46]. This vasodilator effect was fully abolished by endothelial denudation [46], suggesting that the Up4A-induced vascular relaxation in rat aortas is endothelium-dependent.

Matsumoto et al. found a similar contraction pattern induced by Up4A in aortas isolated from Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka rats (LETO), a control to type 2 diabetic Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats (OLETF). In contrast to Sprague Dawley rats, Up4A-induced contraction was endothelium-dependent [72]. Moreover, upon PE-induced preconstriction, Up4A produced a concentration-dependent contraction, which was further enhanced by NOS blockade, while Up4A induced relaxation in the presence of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition [72]. Hence, studies in both Sprague Dawley and LETO rats indicate that there is an endothelium-dependent attenuation of Up4A-induced vasoconstriction. The difference in vascular effect between these two rat strains may be due to increased generation of predominant vasoconstrictor prostanoids PGF2α and thromboxane (TxA2) over the vasodilator prostanoid PGE2 in the LETO rats [72].

4.1.2. Mice

A mild and transient vascular contraction was observed by Hansen et al. [13] and Zhou et al [9, 20] when a cumulative Up4A concentration response was performed under basal conditions in C57BL/6 mouse aortas. In isolated aortas preconstricted with PE, Up4A produced a significantly more pronounced vascular contraction of 18±2% and 76±16% at concentrations of 10−7 and 10−6 M, respectively. At 10−5 M, Up4A caused a transient contraction followed by a dominant relaxation (~40%) [9, 13]. This transient relaxation is unlikely due to the desensitization of purinergic receptors, as vascular contraction reappeared at an even higher concentration of Up4A (5×10−5 M) [13].

Notably, a single concentration of 10−5 M Up4A resulted in intense contraction [13]. In a lower concentration range and with the application of a single concentration, Up4A-mediated vascular contraction in preconstricted mouse aortas was significantly attenuated by the non-selective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor indomethacin [13] as well as by COX1, but not COX2-inhibition [9], suggesting the involvement of vasoconstrictor prostanoids. Furthermore, Up4A-induced aortic contraction was blunted by the TxA2 synthase (TXS) inhibitor ozagrel and TxA2 receptor (TP) antagonist SQ29548, respectively [9]. Altogether, these data imply a role for the COX1-TXS-TxA2 pathway in Up4A-induced aortic contraction in mice. Previous studies demonstrated that activation of A1R and A3R results in vascular contraction via TxA2 production [73, 74]. Zhou et al. however found that A3R deletion had no effect on Up4A-induced contraction, and that A1R or A1/A3R deletion using A1R knockout (KO) mice or A1/A3R double KO (DKO) mice and pharmacological blockade with an A1R antagonist potentiated Up4A-induced aortic contraction, likely due to an interaction between A1R and the vasodilator P2Y1R [9]. Further, the non-selective purinergic P2 receptor antagonist PPADS significantly blunted Up4A-induced aortic contraction to a similar extent as the selective P2X1R antagonist MRS2159 [9]. In contrast to the concept that activation of P2Rs on endothelial cells leads to vasodilation, while activation of P2Rs on smooth muscle cells results in vasoconstriction, endothelial denudation almost fully blocked Up4A-induced contraction, suggesting that Up4A-induced vascular contraction is mainly endothelium-dependent. A constrictor effect of P2XR on endothelium is further supported by studies showing that ATP-induced activation of endothelial P2XR [75] or NADPH-induced stimulation of P2X1R lead to vascular contraction [54]. Taken together, Up4A-induced vascular contraction in mouse aortas depends on activation of TXS and TP, which is mediated, at least in part, through activation of endothelial P2X1R but not AIR or A3R.

4.2. Pulmonary arteries

4.2.1. Rats

Gui et al. characterized the effect of Up4A on pulmonary vascular tone in Sprague Dawley rats using isometric tension recording. Up4A (10−8-10−4 M) produced a concentration-dependent contraction in isolated rat pulmonary arteries [76]. In contrast to the observations in rat aortas [6, 46], endothelium-denudation had no effect on Up4A-induced pulmonary contraction [76]. Similarly, Matsumoto et al. showed that NOS blockade failed to enhance Up4A-mediated pulmonary contraction [18]. Following preconstriction however, Gui et al. observed a mild relaxation at a concentration of 10−6 M Up4A [76], which was abrogated by endothelial denudation [76], suggesting the presence of a slight endothelium-dependent Up4A-mediated pulmonary relaxation.

Up4A-induced contraction in intact pulmonary arteries in the absence of preconstriction was attenuated by the non-selective P2YR antagonist suramin but not by the non-selective P2XR antagonist Ip5I or P2X1R desensitizer α, β-methylene-ATP [76]. Moreover, Up4A-induced contraction in isolated pulmonary arteries was as potent as UTP (a ligand that favors both P2Y2R and P2Y4R) and UDP (a ligand that favors P2Y6R) in endothelium-denuded arteries, while much more effective than UTP and UDP in endothelium-intact preparations [76]. These findings suggest that Up4A induces contraction mainly through activation of P2YR (not only P2Y2R, P2Y4R and P2Y6R but also other P2YRs) but not P2XR. As for the post-receptor signaling, Up4A-mediated pulmonary contraction was blocked by thapsigargin, an inhibitor that blocks Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and EGTA (a Ca2+ chelator), but was not affected by Rho-kinase inhibition with H-1152 [76]. These observations indicate that the contractile effect of Up4A on pulmonary arteries involves the entry of extracellular Ca2+ and release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores but not Ca2+ sensitization of the myofilaments due to the activation of RhoA/Rho kinase pathway in VSMCs.

4.3. Coronary vasculature

4.3.1. Swine

Zhou et al. found that Up4A in concentrations of up to 10−5 M failed to produce an appreciable vasoconstrictor response in porcine coronary small arteries at baseline, but rather induced potent relaxation up to 100% when vessels were preconstricted [12]. Up4A-induced relaxation in porcine coronary small arteries is as potent as the effect by well-studied mono-nucleot(s)ide vasodilators such as adenosine, ATP and ADP [12]. This vasodilator effect by Up4A is not mediated by potential degradation to adenosine, as it was not affected by inhibition of ecto-nucleotidase [12]. A significant part of the vasodilator response to Up4A in porcine coronary small arteries is mediated by activation of A2AR located on both endothelium and smooth muscle cells [12]. Moreover, Zhou et al. observed that vessel size and/or age of the animals might affect the involvement of P2-receptor subtypes in Up4A-mediated coronary relaxation. Thus, Up4A-mediated relaxation was not affected by P2X1R inhibition in coronary arteries with diameter of ~250 μm from swine with an age of 6 months [12], but was significantly attenuated by both P2X1R and P2Y1R inhibition in vessels with diameter of ~150 μm from animals with an age of 4-5 months [21, 77]. Accordingly, the P2X1R, that was not detectable in vessels with diameter of ~250 μm, was expressed in vessels with diameter of ~150 μm [21, 77]. This observation suggests an increased involvement of purinergic receptors in smaller vessels [78]. In coronary arteries with diameter of ~150 μm from animals with an age of 9 months however, only P2X1R but not P2Y1R was involved in Up4A-induced relaxation [24], suggesting a decreased involvement of purinergic receptors during life [79]. Taken together, in the porcine coronary vasculature, the involvement of purinergic receptor subtypes in Up4A-mediated relaxation may differ in vessels with different diameters and/or vessels of animals with different ages.

Zhou et al. further found that Up4A-induced coronary relaxation in swine was attenuated by NOS/COX blockade as well as endothelium-denudation [12]. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP 2C9), of which the metabolites may also act as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarization factor (EDHF) [80], had no effect on Up4A-mediated coronary relaxation from swine with ages of 4-6 months either in the absence or presence of NOS/COX blockade (unpublished). Of note, CYP 2C9 inhibition, in the presence of NOS/COX blockade, potentiated Up4A-induced coronary relaxation in swine with an age of 9 months [24]. These data are consistent with the notion that CYP 2C9 activity increases with age [81], but predominantly produces ROS in healthy porcine coronary small arteries [82, 83]. Taken together, these findings suggest that Up4A-mediated porcine coronary relaxation is partly endothelium-dependent, while the involvement of CYP 2C9 metabolites in Up4A-mediated coronary relaxation depends on age of animals.

4.3.2. Mice

In epicardial arteries isolated from C57BL/6 mice, Teng et al. found that Up4A barely induced vascular contraction at baseline but produced a mild contraction when the vessel tone was elevated [10]. In isolated mouse hearts, continuous infusion of Up4A (10−9-10−5 M) resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease in coronary flow (~22%), consistent with a vasoconstrictor influence of Up4A in the murine coronary microcirculation [10]. This vasoconstrictor influence involved activation of P2X1R. The more potent vasoconstrictor effect observed in isolated mouse hearts as compared to epicardial arteries may be due to a more abundant expression of P2X1R in the coronary microvasculature [84]. Interestingly, a bolus injection of a high dose of Up4A (i.v., 1.6 mg/kg) into anesthetized mice resulted in an increase in heart rate and decreases in stroke volume and cardiac output, and more than a 2-fold increase in coronary blood flow as compared to baseline [10]. When measuring the vasoactive effects of Up4A in vivo it should be taken into account that circulating hormones, nerve-activity, flow and blood components may influence this effect either directly or indirectly. Moreover, the net vasodilator effect of Up4A observed in vivo is a combination of the direct vasodilator effect from Up4A-activated NO in some types of arteries e.g. rat aortas [46] and the indirect vasodilator effect from Up4A-activated vasodilator purinergic receptors in non-vascular cells (e.g. erythrocytes) outweighing the direct vasoconstrictor effect from Up4A-activated vasoconstrictor purinergic receptors (P1R/P2X1R-ROS pathway) in the vessel wall. Finally, it is possible that intravenous injections of Up4A in vivo predominantly stimulate the endothelial vasodilator purinergic receptors, whereas in isolated vessel experiments in vitro, purinergic receptors on VSMC are also reached. Future studies are needed to address these issues.

4.4. Renal vasculature

4.4.1. Rodents

In the main branches of renal arteries isolated from Wistar rats, Matsumoto et al. found that Up4A produced a mild contraction, which was enhanced by NOS blockade [18]. The contraction was sensitive to blockade of suramin-sensitive P2YR but not to P2XR-antagonism with Ip5I (diinosine pentaphosphate pentasodium salt hydrate) [18]. Jankowski et al. observed that Up4A acted as a strong vasoconstrictor on renal afferent arterioles, but had no significant effect on the efferent arterioles in C57BL/6 mice [25]. The selective preglomerular vasoconstrictor activity of Up4A may be due to the lack of P2X1R in postglomerular arterioles, as the P2X1R has been found to be absent in postglomerular arterioles of rats [85].

As outlined above, Up4A can be synthesized in renal tubular cells [25], which may affect renal perfusion and further contribute to regulation of renal vascular tone [86, 87]. Jankowski et al. investigated the effect of Up4A in perfused kidneys isolated from Wistar rats and demonstrated that Up4A dose-dependently (10−11 to 10−7 M) increased renal microvascular resistance [6], suggesting a potent vasoconstrictor effect. This potent vasoconstrictor effect was further increased in the presence of NOS inhibition, while it was attenuated by the non-selective P2R antagonist Ip5I and the P2X1R desensitizer α, β-methylene-ATP [6] as well as by extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) inhibition. The remaining vasoconstrictor effect of Up4A after P2X1R blockade was shown to be attributable to the P2YR (most likely P2Y2R)-mediated long-lasting activation [88]. The Ip5I antagonizes multiple P2XRs including P2X1R [33]. The observation that P2X1R blockade reduced Up4A-induced vasoconstriction in isolated perfused kidneys but not in isolated renal arteries is consistent with a more dense P2X1R expression in smaller vessels (e.g., renal resistance arteries) as compared to relatively larger vessels (e.g., main branch of renal arteries) [84].

Following preconstriction of the renal vasculature with angiotensin (Ang) II, Up4A initially induced a further dose-dependent constriction followed by a dose-dependent vasodilation of the isolated perfused rat kidney [88]. This suggests that, also in the renal vasculature, Up4A is capable of inducing vasodilation in addition to vasoconstriction. Up4A-mediated renal vasodilation was inhibited by the non-selective P2R antagonists (suramin, PPADS, and RB2) and the selective P2Y1R antagonist MRS2179 [88], suggesting that Up4A-induced renal vasodilation is exerted through P2Y1R and possibly P2Y2R. Tölle et al. further found that the Up4A-induced renal vasodilation was decreased in the presence of NOS inhibition or endothelium-denudation, suggesting that endothelial NO production contributes to Up4A-induced renal vasodilation [88]. Altogether, these data suggest that Up4A contributes to renal hemodynamics and blood pressure regulation. Furthermore, Up4A may contribute to fluid homeostasis through the regulation of glomerular perfusion, intraglomerular pressure, and glomerular filtration rate.

4.5. Other vascular beds

Matsumoto et al. compared the vasoactive effects of Up4A in basilar arteries, mesenteric arteries and femoral arteries from Wistar rats in vitro. They found that Up4A (10−9−3×10−5 M) produced a concentration dependent contraction at baseline in all of those vascular beds, but the magnitude of Up4A-induced contraction in those vascular beds was very different with the highest contraction of ~60% in basilar and the lowest contraction of ~20% in femoral arteries, whereas contraction of the mesenteric arteries was ~40% [19]. Similarly, Zhou et al. observed a ~25% contraction induced by 10−5 M Up4A in rat mesenteric arteries at baseline [77].

Hansen et al. observed hypotension (~6 mmHg decrease in mean arterial blood pressure induced by 128 nmol/kg/min Up4A in rats and ~35 mmHg decrease induced by 512 nmol/kg/min Up4A in mice) when Up4A was infused via femoral vein [13], indicating that Up4A induces systemic vasodilation. This observation seems to be in contrast with the observation that Up4A acts as a mild to potent vasoconstrictor in most of vessels isolated from systemic vascular beds. This difference is not readily explained, but may be due to several possibilities as discussed above (see mouse coronary section). Thus, there is a large heterogeneity of Up4A-induced vascular responses i.e. Up4A produces both/either contraction and/or relaxation. This may be attributed to different expression/distribution and receptor density in different vascular beds and in corresponding vascular beds in different species. The vascular effects of Up4A in various vascular beds of different species and the involvement of purinergic signaling are summarized in Table 1 (vasoconstrictor effect of Up4A) and Table 2 (vasodilator effect of Up4A), respectively.

Table 1.

Vasoconstrictor effect of Up4A in various vascular beds of different species

| Vascular beds |

Arterial segments |

Diameter | Condition | Species | Vascular influence |

Maximal effect |

Receptors | Pathways | Delivery | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aorta | Intact aortas | Basal tone | Rat (Wistar) |

Increased mean arterial blood pressure | Intraarterial bolus injection in anesthetized rats | Jankowski et al. [6] | ||||

| Isolated thoracic aortas | Basal tone | Rat (SD, Wistar) |

Contraction | ~40% | P1Rs, P2X1R | Effect suppressed by NO | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Linder et al. [46], Masumoto et al. [19] | ||

| L-type Ca2+ channel | ||||||||||

| Rho kinase | ||||||||||

| NADPH-derived ROS | ||||||||||

| Isolated thoracic aortas | Basal tone | Rat (LETO) |

Contraction | ~60% | Endothelial dependent | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Matsumoto et al. [72] | |||

| Isolated thoracic aortas | Elevated tone* | Rat (LETO) |

Contraction | ~20% | Effect suppressed by NO PGF2α; TxA2 | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Matsumoto et al. [72] | |||

| Isolated thoracic aortas | Basal tone | Mouse | Transient and mild contraction | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Zhou et al. [9], Hansen et al. [13] | |||||

| Isolated thoracic aortas | Elevated tone* | Mouse | Contraction | >70% | P2X1R, A1R, AT1 | COX1-derived TxA2; TP | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Zhou et al. [9], Hansen et al. [13] | ||

| Pulmonary artery | Isolated pulmonary arteries | 1-1.5 mm | Basal tone | Rat (SD, Wistar) |

Contraction | ~60% | P2Y2R, P2Y4R, P2Y6R and other P2YRs | Ca2+ (extracellular/intracellular stores) | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Gui et al. [76], Matsumoto et al. [18] |

| Coronary vasculature | Perfused hearts | Basal tone | Mouse | Decreased coronary flow | ~20% | P2X1R | Continuous infusion | Teng et al. [10] | ||

| Isolated coronary arteries | ~100 μm | Elevated tone* | Mouse | Contraction | ~8% | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Teng et al. [10] | |||

| Renal vasculature | Perfused kidneys | Basal tone | Rat (Wistar) |

Increased perfusion pressure | >100 mmHg | P2X1R, P2Y2R | Effect suppressed by NO | Continuous infusion | Jankowski et al. [6], Tolle et al. [88] | |

| Perfused kidneys | Basal tone | Mouse | Vasoconstriction in afferent arterioles | ~20% change in diameter | P2X1R | Continuous infusion | Jankowski et al. [25] | |||

| Isolated renal arteries | Basal tone | Rat (Wistar) |

Contraction | ~20% | P2YRs | Effect suppressed by NO; ERK | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Matsumoto et al. [18] | ||

| Others | Isolated mesenteric arteries | <100 μm | Basal tone | Rat (Wistar) |

Contraction | ~40% | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Matsumoto et al. [19] | ||

| Isolated basilar arteries | Basal tone | Rat (Wistar) |

Contraction | ~60% | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Matsumoto et al. [19] | ||||

| Isolated femoral arteries | Basal tone | Rat (Wistar) |

Contraction | ~20% | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Matsumoto et al. [19] | ||||

AR: adenosine receptors; AT1: angiotensin II receptor type 1; COX: cyclooxygenase; ERK: extracellular signal-related kinase; NO: nitric oxide; PR: purinergic receptors; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TP: thromboxane receptor; TxA2: thromboxane A2. SD: Sprague Dawley; LETO: Long-Evans Tokushima Otsuka rats.

Elevated tone induced by phenylephrine.

Table 2.

Vasodilator effect of Up4A in various vascular beds of different species

| Vascular beds |

Arterial segments |

Diameter | Condition | Species | Vascular influence |

Maximal effect |

Receptors | Pathways | Delivery | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aorta | Isolated thoracic aorta | Elevated tone* | Rat (Wistar) |

Relaxation | ~25% | Endothelium-dependent | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Linder et al. [46] | ||

| Isolated thoracic aorta | Elevated tone* | Mouse | Transient relaxation | ~46%/~41% | Zhou et al. [9], Hansen et al. [13] | |||||

| Pulmonary artery | Isolated pulmonary arteries | 1-1.5 mm | Elevated tone* | Rat (SD) |

Relaxation induced by 10−6 M Up4A | ~10% | Endothelium-dependent | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Gui et al. [76] | |

| Coronary vasculature | Isolated coronary arteries | ~250 μm | Elevated tone† | Pig | Relaxation | ~100% | A2AR | Partially via NO and PGI2 | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Zhou et al. [12] |

| ~150 μm | Elevated tone† | Pig | Relaxation | ~100% | A2AR, P2X1R, P2X7R, P2Y1R, P2Y6R | Partially via NO | Bolus addition in the organ chamber | Zhou et al. [21, 24, 77] | ||

| Coronary circulation | Basal tone | Mouse | Vasodilation | >2 fold increase | Bolus injection i.v. | Teng et al. [10] | ||||

| Renal vasculature | Perfused kidney | Elevated tone** | Rat (Wistar) |

Decreased perfusion pressure | ~60 mmHg | P2Y1R, P2Y2R | NO | Bolus application | Tolle et al. [88] | |

| Others | Systemic circulation in vivo | Basal tone | Rat (SD) |

Decreased mean arterial blood pressure | ~6 mmHg | i.v. infusion | Hansen et al. [13] | |||

| Mouse | ~25 mmHg | i.v. infusion | ||||||||

AR: adenosine receptors; ET: endothelin; NO: nitric oxide; PGI2: prostaglandin; PR: purinergic receptors.

Elevated tone induced by phenylephrine;

Elevated tone induced by angiotensin II;

Elevated tone induced by U46619.

5. Up4A and vascular function under pathophysiological conditions

The plasma concentrations of Up4A are increased in hypertensive (~33 nM) as compared to normotensive (~4 nM) juvenile humans, and the increase in Up4A concentration significantly correlates with the increased left ventricular mass and intima/media wall thickness in hypertensive subjects [6, 11]. Similarly, the average plasma level of Up4A in patients with chronic kidney diseases who undergo hemodialysis is 5.2-fold higher than in healthy controls [17]. The up-regulation of Up4A in disease conditions suggests a role for Up4A in the development of cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, the effect of Up4A on vascular function may be altered in the presence of cardiovascular disease and endothelial dysfunction.

5.1. Hypertension

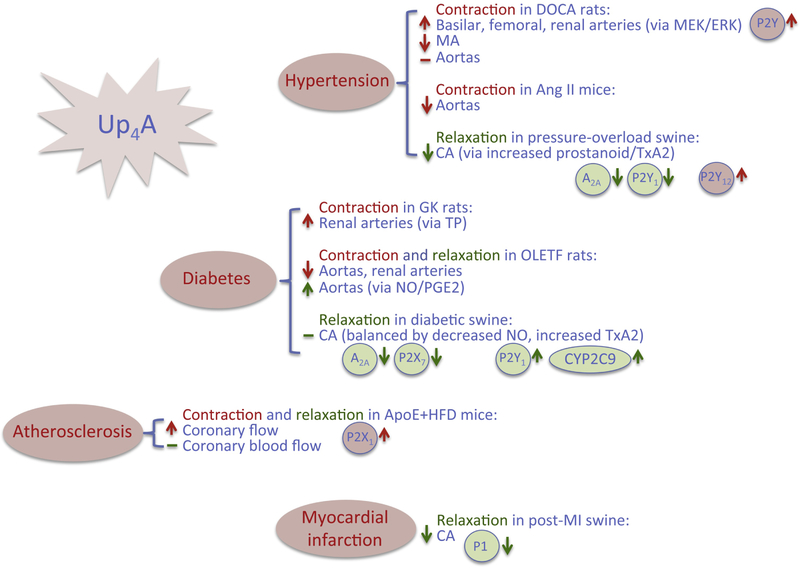

Vascular reactivity to Up4A is altered in hypertension (Fig. 3). Matsumoto et al. investigated the vascular contractile responses of Up4A in various isolated arteries of deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt rats, a salt-dependent experimental model of arterial hypertension. In DOCA-salt rats (vs. control rats): Up4A-induced vascular contraction was 1) increased in basilar, renal, and femoral arteries, 2) decreased in small mesenteric arteries, and 3) unchanged in thoracic aortas and pulmonary arteries [18, 19]. These results suggest that Up4A-induced contraction is heterogeneously affected among various vessels in this model. Activation of P2YR was shown to contribute to the increased Up4A-induced contraction in basilar, femoral, and renal arteries [18, 19]. In the renal arteries, Up4A-stimulated ERK activation was increased and the enhanced Up4A-induced contraction was decreased by MEK/ERK pathway inhibitor (PD98059) [18], suggesting that increased activity of ERK contributes to increased Up4A-induced renal arterial contraction in DOCA-salt rats. However, since the difference in Up4A-induced renal arterial contraction between DOCA-salt and control groups was not completely abolished by ERK inhibition, other signaling pathway(s) likely also contribute to the increased Up4A-induced contraction [18]. Various signal-transduction pathways, such as Rho kinase, epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor transactivation and MAPK, have been shown to be activated upon P2YR stimulation [89-91]. Moreover, these signal-transduction pathways have been shown to be altered in various hypertensive models including mineralocorticoid hypertension [92-95].

Figure 3.

Alteration of purinergic signaling in response to Up4A in various cardiovascular diseases. Red up arrow: increased contractile effect; red down arrow: decreased contractile effect; green up arrow: increased dilating effect; green down arrow: decreased dilating effect. Ang II: angiotensin II; CA: coronary arteries; DOCA: deoxycorticosterone acetate; ERK: extracellular signal-related kinase; GK: Goto-Kakizaki; HFD: high fat diet; MA: mesenteric arteries; MI: myocardial infarction; NO: nitric oxide; OLETF: Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty; TP: thromboxane receptor; TxA2: thromboxane A2.

The effect of hypertension on vascular reactivity to Up4A was further investigated in mice with hypertension induced by chronic infusion of Ang II for 21 days. Contrary to findings in rat aorta, Zhou et al. found in mice aorta that, despite an up-regulation of AT1 and P2X1R protein expression, Up4A-induced contraction was significantly reduced in hypertensive mice as compared to controls, while no difference in KCl- or PE-induced vascular contraction between saline- and Ang II-infused mice was observed [20]. Surprisingly, the impaired contractility to Up4A in hypertensive mice was likely due to P2X1R desensitization rather than to AT1 receptor desensitization [20]. Such desensitization may also exist in vivo, as Up4A infusion in rodents desensitizes purinergic receptors accounting for the lack of increase in blood pressure [6, 13]. Up4A-induced P2X1R desensitization may provide a compensatory mechanism to counteract the hyper-contractility present in the vasculature of hypertensive subjects. Indeed, a chronic increase in renal interstitial ATP concentration in rats with Ang II-induced hypertension induced P2X1R desensitization [96], which is in line with the impaired ATP-induced vasoconstriction in afferent renal arteries in these rats [97]. Altogether, these findings from Zhou et al. imply that vascular purinergic receptor activity rather than circulating Up4A, which has been observed to be increased in hypertension, may determine the role of Up4A in hypertension. However, further studies into the relation between altered circulating Up4A, vascular purinergic receptor activity and downstream changes in signal-transduction pathways activated by Up4A in arterial hypertension are needed.

Hypertension induced by pressure-overload is accompanied by structural abnormalities in the coronary microvasculature as well as by endothelial dysfunction. In a swine model with prolonged pressure-overload induced by aortic banding (AoB), Zhou et al. found that Up4A-induced relaxation in isolated coronary small arteries was blunted in vessels from AoB swine compared to sham-operated swine [21]. Non-selective P1R blockade attenuated Up4A response to the same extent in coronary small arteries of AoB and sham-operated swine, while the contribution of A2AR to the response was abolished in AoB swine. A possible involvement of other adenosine receptors in AoB swine was therefore proposed. Although non-selective P2 receptor blockade blunted the effect of Up4A more in coronary small arteries from AoB as compared to sham-operated animals, P2X1R blockade attenuated Up4A response to the similar extent between AoB and sham-operated swine, while the effect of P2Y1R blockade was lost in vessel from AoB. Expression of the P2Y12R was increased in coronary small arteries from AoB, while expression of other purinergic receptor subtypes involved in vascular tone regulation including A1R, A2AR, A3R, P2X1R, P2X7R, P2Y1R, P2Y2R and P2Y6R was not altered. As for endothelium-derived factors, the authors found that NOS blockade attenuated Up4A-induced relaxation to the same extent in AoB and sham-operated swine, whereas additional COX inhibition had no effect in sham-operated swine, but enhanced Up4A-induced relaxation in AoB, suggesting a production of vasoconstrictor prostanoids in AoB upon Up4A stimulation. Consistent with a link between the vasoconstrictor effect of Up4A and TxA2 production, P2Y12R blockade and/or TxA2 inhibition enhanced the vasodilator response to Up4A in denuded coronary small arteries to the similar extent [21]. This suggests that activation of the P2Y12R may result in TxA2 production in response to Up4A, thereby blunting its vasodilator effect in the coronary microcirculation. Future studies are needed to confirm the direct link between P2Y12R and TxA2.

5.2. Diabetes

Vascular complications including macro- and micro-vascular dysfunction are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in diabetes mellitus [98]. Diabetes is associated with (micro)vascular dysfunction [99, 100], i.e. an imbalance between relaxation and contraction in a wide variety of vascular beds from diabetic patients and animal models [100-105]. However, the extent of vascular dysfunctions differs between ligands, vessel types, sexes, and severity of diabetes.

Several studies have investigated the reactivity to Up4A in arteries from diabetic models (Fig. 3). Matsumoto et al. observed that Up4A-induced contraction was enhanced in renal arteries from Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats [22], a non-obese type 2 diabetic model [106], at 44±2 weeks of age. Using a pharmacological approach, they found that the Up4A-induced contraction of renal arteries was abolished by the non-selective P2R antagonist suramin in both GK and age-matched control Wistar rats [22], indicating that the enhanced Up4A-induced contraction in the diabetic rat renal artery was due to activation of suramin-sensitive P2Rs. However, as the protein expression for P2X1R and P2Y2R was unchanged, it is unlikely that the increased renal contraction to Up4A involves altered activation of those two P2Rs [22]. Diabetes has been shown to be accompanied by changes in the interaction between vasoconstrictors and NO as well as COX-derived prostanoids [100, 107]. In accordance with this concept, Up4A-induced contraction was enhanced by endothelial removal in renal arteries of Wistar rat, whereas such contraction was not affected by endothelial denudation in the GK renal artery. These results suggest that the endothelium can suppress Up4A-induced contraction in healthy subjects and that the enhanced Up4A-induced contraction from GK rats is due to an impaired endothelial function. NOS blockade increased Up4A-induced contraction similarly in Wistar as compared to GK groups [22]. Conversely, the effect of COX-derived prostanoids on Up4A-induced renal artery contraction was altered in GK as compared to Wistar rats. Thus, COX2 inhibition (NS398) reduced the renal arterial contraction induced by Up4A only in the GK but not Wistar group and the differences in Up4A-induced contraction between GK and Wistar groups were abolished following non-selective COX inhibition (indomethacin), selective COX1 inhibition (valeroyl salicylate) as well as the TP receptor antagonist (SQ29548) in renal arteries from both GK and Wistar rats [21]. In accordance with these findings, the protein expressions of COX1 and COX2 in renal arteries were increased in GK group. Surprisingly, the release of TxA2 induced by Up4A was similar between two groups [22], but sensitivity to the TP receptor agonist U46619 was enhanced in renal arteries of GK rats (vs. Wistar rats) [22]. These results imply that the enhanced Up4A-induced contraction in the renal arteries from type 2 diabetic GK rats is attributable to increased sensitivity to TP receptors rather than the production of TxA2. Future investigations are required to study the production of vasoconstrictor prostanoids including other prostanoids and activities of each COX-subtype upon Up4A stimulation in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. In addition, the specific P2R that couples the response of Up4A to increased TP sensitivity in type 2 diabetes remains to be identified.

Using Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) type 2 diabetic rats, a strain that gradually develops high blood glucose after birth with obesity, thereby resembling human type 2 diabetes with obesity [108], Matsumoto et al. investigated the vascular effects of Up4A in aortas and renal arteries. Up4A-induced contraction was decreased in aortas of the OLETF rat as compared to control LETO rats at baseline without preconstriction [72]. The decreased contraction may provide a compensatory mechanism to counteract the hyper-vascular contractility present in diabetes and hypertension. With elevated tone, Up4A produced a mild relaxation in aortas from OLETF rats as compared to the vasoconstrictor effect in LETO rats [72]. In healthy LETO rats in the absence and presence of preconstriction, the endothelium predominantly released vasoconstrictors i.e. vasoconstrictor prostanoids PGF2α and TxA2 in response to Up4A, facilitating its vasoconstrictor effect. Conversely, the endothelium produced vasodilators i.e NO and the vasodilator prostanoid PGE2 suppressing Up4A effects in OLETF rats [72].

Similar to aortas, Up4A-induced contraction in renal arteries was decreased in the OLETF rat as compared to control LETO rats at age of 4 months in the absence of preconstriction [72]. Of note, the Up4A-induced renal contraction in OLETF rats was enhanced with age and duration of diabetes (i.e., 18 vs. 4 months old), whereas there was no age-associated effect on the Up4A-induced contraction in LETO rats [23]. Furthermore, an age-related enhancement of contraction induced by PE was also observed in renal arteries from OLETF rats but not LETO rats [23]. Altogether, these findings suggest that the contractile responses to Up4A were mainly influenced by the duration of diabetes, as aging did not influence these renal arterial contractions under the non-disease condition. Matsumoto et al. further investigated the relationship between endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and Up4A-induced contraction in renal arteries from OLETF rats. Treatment with an ER stress inhibitor (tauroursodeoxycholic acid, i.p.) for 1 week slightly reduced the Up4A-induced renal arterial contraction in 12 month-old OLETF rats (vs. vehicle treatment group) [23]. The vasoconstrictor effect was abolished in the presence of COX inhibition to a similar extent between OLETF and LETO rats [23]. Moreover, expression of ER stress-related genes as well as COX1 was increased in renal arteries from OLETF rats during aging [23]. These findings suggest that increased reactivity to Up4A in renal arteries of type 2 diabetes with age may be attributable to increased ER stress and COX activity.

Interestingly, Up4A-induced coronary relaxation was maintained in swine with metabolic derangement (diabetes induced by streptozotocin in combination with high fat diet) compared to normal swine, despite impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation to bradykinin [24]. Indeed, eNOS mRNA expression, as well as expression of the vasodilator A2AR and P2X7R was reduced in isolated coronary small arteries from swine with metabolic derangement [24]. Zhou et al. further investigated the mechanisms involved in Up4A-induced coronary relaxation and found that there was a balanced but altered cross-talk among purinergic signaling and endothelium-derived vasoactive factors. Thus, there was a decreased P2X7R and NO-mediated vasodilator influence of Up4A, while a TxA2-mediated vasoconstrictor influence was unmasked [24]. These alterations acting to increase vasoconstriction were balanced by an increased vasodilator influence via P2Y1R and CYP 2C9 switched from producing vasoconstrictor to vasodilator metabolites in swine with metabolic derangement [24].

The local and circulating levels of Up4A are currently unknown in diabetes. Given the altered expression of total and phosphorylated VEGFR2, the putative enzyme for Up4A biosynthesis, in diabetes [109, 110], circulating Up4A level is likely to be increased in diabetes. It would therefore be of interest to investigate whether altered Up4A biosynthesis affects subsequent purinergic signaling contributing to vascular dysfunction in diabetes.

5.3. Coronary atherosclerosis

Coronary plaque formation due to atherosclerosis is an important cause of ischemic heart disease, one of the leading causes of death worldwide [111, 112]. When coronary plaques rupture or erode, the ensuing thromboembolism often leads to cardiac ischemia and infarction [112]. Myocardial tissue injury promotes the release of extracellular nucleot(s)ides, which subsequently activate and/or alter purinergic signaling [70]. Pharmacological vasodilation with ATP and/or adenosine is commonly used to investigate the severity of coronary artery stenosis, while the purinergic P2Y12R antagonist clopidogrel is commonly used reduce plaque formation and improve plaque stability in patients with coronary artery disease [69]. Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that purinergic receptor expression is altered in atherosclerosis. Thus, in coronary arteries isolated from ApoE knockout mice on a high fat diet, there was a dramatic decrease in P2X1R expression in endothelial cells, while P2X1R expression remained unaltered in VSMCs [10]. Hence, the smooth muscle to endothelial cell ratio of P2X1R expression was enhanced, suggesting a net vasoconstrictor potential of P2X1R in coronary atherosclerosis [10]. Consistent with these findings in the murine coronary conductance arteries, infusion of Up4A (10−9-10−5 M) into isolated hearts from ApoE knockout mice with high fat diet, in which coronary lesions were observed, decreased coronary flow more as compared to hearts from control mice (Fig. 3) [10]. The exaggerated decrease in coronary flow was reversed by P2X1R antagonism, suggesting a functional role of the P2X1R on VSMC in Up4A-mediated coronary microvascular contraction. In contrast to ex vivo findings, a bolus injection of Up4A (1.6 mg/kg) into the femoral vein of these mice increased coronary blood flow to a similar extent (more than 2-fold increase compared to baseline) between control and atherosclerotic mice [10]. It is important to note that Up4A injection resulted in an increase in heart rate and decreases in stroke volume and cardiac output in control, which may have resulted in metabolic alterations in coronary blood flow. However, heart rate and cardiac output did not change in response to Up4A in atherosclerotic mice [10], suggesting a direct effect of Up4A on coronary flow regulation in atherosclerosis.

5.4. Myocardial infarction

Zhou et al. investigated the effect of Up4A on coronary microvessels from swine that underwent myocardial infarction (MI) (Fig. 3). The authors found that Up4A concentration response curve was shifted rightwards in coronary small arteries from the non-infarcted remote territory of swine with MI as compared to sham-operated swine, with no change in maximal vasodilator response, indicating reduced sensitivity of the coronary microvasculature to Up4A after MI [77]. The reduced response to Up4A in remote coronary microvessels after MI is consistent with their in vivo observation, that coronary vasodilation to ATP, which is mediated via activation of purinergic receptors and subsequent NO production, was reduced after MI [113]. Nevertheless, NOS inhibition attenuated the vasodilator response to Up4A similarly in vessels from MI and normal swine [77]. The reduced vasodilator response to Up4A appeared to be due to a reduced contribution of P1R, as the attenuation of Up4A-induced vasorelaxation by non-selective P1R blockade was significantly less in MI as compared to sham-operated swine. This reduced response involved P1R subtypes other than A2AR, as both the attenuation of the vasodilation with selective A2AR blockade, and the A2AR mRNA levels were comparable in sham-operated and MI swine [77]. Future studies are required to test a possible involvement of loss of A2BR in the coronary microvasculature particularly after MI. Their study of the contribution of P2R to the reduced response to Up4A was limited. Neither non-selective P2 blockade with PPADS, nor selective P2X1R inhibition with MRS2159 and P2Y1R inhibition with MRS2179 differentially affected Up4A-induced coronary relaxation between sham-operated and MI swine, which was in accordance with a similar expression of those receptors between the two groups [77].

6. Up4A and its long-term (trophic) actions

Like other nucleotides [114], Up4A exerts various long-term actions on endothelial and VSMCs as well as on monocytes (Table 3), that may contribute to structural physiological and pathological changes in the vasculature.

Table 3.

Up4A-induced trophic actions

| Experimental model | Duration | Vascular influence | Maximal effect | Receptors | Pathways | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HUVEC, HMVEC, HCAEC | 5 days | Angiogenesis | P2Y6R | VEGFA | Zhou et al. [14] | |

| Human VSMC | 2 days | Proliferation | P2YRs | Jankowski et al. [11] | ||

| Human VSMC | 5 days | Proliferation | as potent as ATP and UTP | PI3K/Akt, MAPKs | Gui et al. [15] | |

| Rat VSMC | 2-24 h | MCP-1 formation | P2Y2R | NOX1-derived ROS, MAPKs | Schuchardt et al. [119] | |

| Rat VSMC | Up to 24 h | Migration, OPN expression/secretion | P2Y2R | ERK1/2, PDGFR | Wiedon et al. [16] | |

| Rat aorta/VSMC, mouse aorta | Up to 30 days | Calcification, Cbfa1 expression | P2Y2R, P2Y6R | MEK, ERK1/2 | Schuchardt et al. [17] | |

ERK: extracellular signal-related kinase; HCAEC: human carotid arterial endothelial cells; HMVEC; human microvascular endothelial cells; HUVEC: human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MAPK: mitogen activated protein kinase; MCP-1: Monocyte chemotactic protein 1; NOX1: NADPH oxidase isoform 1; PDGFR: platelet-derived growth factor receptor; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PR: purinergic receptors; ROS: reactive oxygen species; VEGFA: vascular endothelial growth factor A; VSMC: vascular smooth muscle cells.

6.1. Angiogenesis

Zhou et al. explored the effect of Up4A on angiogenesis in human endothelial cells of different origins. A tubule formation assay was performed using a three-dimensional system, in which human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human microvascular endothelial cells (HMVECs) were co-cultured with pericytes up to 5 days. Zhou et al. found that there was no difference in initial tubule formation between Up4A stimulation and control conditions at day 2 [14]. In contrast, Up4A at day 5 with an optimal concentration of 5 μM significantly promoted tubule length, number of tubules as well as number of junctions [14], indicating an angiogenic response. However, an increase in tubule formation was not detected at day 5 if Up4A was added at day 2, suggesting Up4A stimulation during early sprouting is required to enhance vascular growth [14]. Of note, Up4A-promoted tubule formation in both HUVECs and HMVECs was attenuated by P2Y6R inhibition using its selective antagonist MRS2578 [14], indicating the involvement of P2Y6R. The Up4A-mediated angiogenic response in the co-culture system is associated with up-regulation of P2YR as well as proangiogenic factors [69]. Thus, Up4A increased mRNA levels of P2Y2R, P2Y4R and P2Y6R, of which the increase in P2Y2R and P2Y6R mRNA levels was attenuated by MRS2578 [14]. However, Up4A had no effect on mRNA level of P2XRs (P2X4R and P2X7R) or P1Rs (A2AR and A2BR). In addition to its effect on mRNA levels of P2Y receptors, Up4A up-regulated mRNA levels of the proangiogenic genes VEGFA, ANGPT1 but had no effect on expression of VEGFR2, ANGPT2, Tie1 and Tie2 in HUVECs. In accordance with its increased mRNA, Up4A also increased protein level of VEGFA in human carotid artery endothelial cells [14]. Altogether, available evidence suggests that Up4A acts as a novel angiogenic substance, which promotes sprouting and tubule formation in human vascular endothelial cells. This Up4A proangiogenic function is mediated via P2Y6R signaling and is associated with up-regulation of P2YRs and other proangiogenic factors.

6.2. Vascular remodeling and atherogenesis

Jankowski et al. showed that Up4A induced VSMC proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner [11]. Up4A-induced VSMC proliferation was abolished in the presence of the non-selective P2R antagonists suramin and PPADS, respectively, but not significantly affected by the non-selective P2XR antagonist Ip5I [11]. These observations suggest that Up4A-induced proliferation is likely mediated via P2YR rather than P2XR. Similarly, Gui et al. found that treatment with Up4A (1-100 μM) for up to 5 days resulted in a time- and concentration-dependent proliferative effect in human VSMCs [15]. The proliferative effect of Up4A was comparable to that of ATP and UTP that also stimulates the P2Y1R, P2Y2R and P2Y4R [15]. Based on the Up4A-P2YR signaling involving in VSMC proliferation, Gui et al. further investigated involvement of post-purinergic receptor signaling and found that the Up4A-induced VSMC proliferation was mediated through the PI3-kinase/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, leading to the independent activation of S6K and an increase in cycle-dependent kinase 2 expression [15]. The increased proliferation of VSMCs may not only be involved in microvascular remodeling but may also contribute to atherogenesis [115-117].

Schuchardt et al. studied the effect of Up4A on formation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), an important early component of the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis, induced by oxidative stress [116, 118]. VSMCs were stimulated with Up4A. 4 h of incubation with Up4A (0.1-100 μM) induced a concentration-dependent increase in MCP-1 mRNA expression. Upon prolonged (24 h) Up4A stimulation (1-100 μM) MCP-1 protein secretion was increased [119]. This Up4A-induced increase in MCP-1 expression was attenuated by the non-selective P2R antagonist suramin, but not by other non-selective P2R antagonists PPADS and RB-2 or the specific P2Y1R antagonist MRS2179 [119]. This effect of Up4A was mimicked by the P2Y2R agonist ATPγS (1-100 μM) induced a concentration-dependent increase in MCP-1 expression and protein secretion, which was significantly diminished by suramin [119]. These findings indicate that Up4A-induced MCP-1 formation is likely mediated through activation of the suramin-inhibitable P2Y2R in VSMCs. Several findings suggest a role for NADPH oxidase (NOX) in this process. Thus, Up4A-induced MCP-1 formation was suppressed by the NOX inhibitor apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium as well as by NOX1 silencing [119]. Furthermore, Up4A dose-dependently increased NOX1 mRNA level and stimulated Rac1 activation and p47phox translocation from cytosol to the plasma membrane, which is required for assembling and activation of NOX. Incubation with Up4A resulted in an increase in superoxide, which was subsequently converted to H2O2. Up4A-induced H2O2 production was diminished by suramin and apocynin, while Up4A failed to increase ROS in VSMCs lacking NOX1[119]. Finally, Up4A-mediated intracellular signal transduction involved activation of MAPKs (i.e. ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK) [119]. These observations demonstrate that Up4A induces NOX1-dependent ROS production, which further stimulates MCP-1 formation through MAPK phosphorylation and activation in VSMCs. Up4A-induced ROS production is not only present in in vascular cells. Schepers et al. found that Up4A has a stimulatory effect on the oxidative burst response of non-stimulated and N-formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine-(fMLP)-activated monocytes. Up4A-induced ROS production was also observed in both monocytes and lymphocytes after stimulation of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) [120]. Thus, Up4A is a potent inducer of proinflammatory response, which may further contribute to the development of atherosclerosis.

Wiedon et al. investigated the potential effect of Up4A on migration in VSMCs. Up4A (0.1-10 μM) induced a concentration-dependent stimulation of VSMC migration, which was not affected by the nucleotidase apyrase [16]. The Up4A-mediated migration in VSMCs was attenuated by the non-selective purinergic receptor antagonists suramin, PPADS and RB-2 but not by the selective P2Y1R and P2Y6R antagonists MRS2179 and MRS2578, respectively [16]. The effect of Up4A on migration may be mediated by osteopontin (OPN), as OPN mRNA and protein increased upon Up4A stimulation of VSMCs [16]. OPN is overexpressed in human vessels showing intimal thickening and is thought to play an important role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis [121]. Thus, OPN expression and secretion play a key role in both UTP-induced VSMC migration [122] and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-directed migration [123]. Up4A-induced increase in OPN mRNA level was abolished by suramin [16], suggesting that OPN-dependent migration is mainly mediated by P2Y2R. The signaling mechanism downstream from the P2R involves activation of the ERK1/2 pathway as well as through transactivation of the PDGF receptor [16].

Schuchardt et al. examined the effect of Up4A on aortic calcification. Stimulation of aortic rings with calcifying medium (CM) resulted in mineralization of the media. Addition of Up4A further increased this mineral deposition in the media [17]. Similarly, CM induced a time-dependent mineral deposition in cultured VSMCs, which was further enhanced with stimulation of Up4A [17]. These findings suggest that Up4A is capable of increasing calcification of VSMCs ex vivo and in vitro. This effect of Up4A was mediated by enhanced expression of different genes specific for osteochondrogenic VSMCs including Cbfa1, while Up4A decreased the expression of a VSMC marker SM22α [17]. The increased Cbfa1 expression induced by Up4A was mimicked by the P2Y6R agonist inosine diphosphate and was significantly attenuated in the presence of suramin, PPADS, RB-2, and the specific P2Y6R antagonist MRS2578 [17]. Moreover, the P2Y2R agonist ATPγS as well as UTP, which activates both P2Y2R and P2Y4R, stimulated Cbfa1 mRNA expression [17]. As the P2Y4R is minimally expressed in VSMCs, these data collectively suggest a prominent role for P2Y2R and P2Y6R. A role for P2Y2R was confirmed by the observation that Up4A potentiated the CM-induced increase in calcium content in aortic rings from WT but not P2Y2R KO mice [17]. Downstream mechanisms of P2YR signaling involved phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated kinases MEK and ERK1/2 [17]. Thus, Up4A activation of P2YRs influences phenotypic transdifferentiation of VSMCs to osteochondrogenic cells.

In conclusion, in addition to its effect on vasomotor tone, Up4A is capable of inducing angiogenesis in endothelial cells, as well as inducing proliferation and migration in smooth muscle cells, increasing calcification in vitro and ex vivo and may contribute to vascular remodeling and atherogenesis. All those chronic effects are mediated through activation of P2YRs.

7. Conclusions and perspectives

As the first dinucleotide that contains both purine and pyrimidine moieties, Up4A exerts both short-term and long-term vascular effects through P1R, P2R as well as non-purinergic signaling pathway in health and disease. Vascular effects induced by Up4A are not only vessel types- but also species-dependent. The involvement of purinergic receptor subtypes in response to Up4A is altered in various cardiovascular diseases. There is only limited evidence available suggesting that circulating Up4A levels are altered in cardiovascular disease, more specifically, in hypertension and chronic kidney disease. Although the vasoactive effect of Up4A may rely more on receptor activity than circulating Up4A level, the precise contribution of the elevated Up4A plasma levels to vascular dysfunction in other forms of cardiovascular disease requires further investigation. Moreover, it should be explored whether the increased Up4A plasma level in hypertension and possibly in other cardiovascular diseases may serve as a diagnostic biomarker, and/or more importantly a causative factor. Targeting Up4A biosynthesis as well as subsequent purinergic signaling may improve vascular function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Southwestern Medical University China Grant MEPSCKL201301 (to ZZ), the Karolinska Institutet Grant (to ZZ), the Loo och Hans Ostermans Stiftelse from Karolinska Institutet (to ZZ), the Olausson Fund from Thorax of Karolinska University Hospital (to ZZ), the Sigurt and Elsa Goljes Memorial Foundation (to ZZ) and NIH-HL027339 (to SJM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest:

None

Declaration of interest

None

References

- [1].Ralevic V, Burnstock G, Involvement of purinergic signaling in cardiovascular diseases, Drug News Perspect 16(3) (2003) 133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ralevic V, Dunn WR, Purinergic transmission in blood vessels, Auton Neurosci 191 (2015) 48–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Burnstock G, Control of vascular tone by purines and pyrimidines, Br J Pharmacol 161(3) (2010) 527–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tolle M, Jankowski V, Schuchardt M, Wiedon A, Huang T, Hub F, Kowalska J, Jemielity J, Guranowski A, Loddenkemper C, Zidek W, Jankowski J, van der Giet M, Adenosine 5'-tetraphosphate is a highly potent purinergic endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor, Circ Res 103(10) (2008) 1100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jankowski V, van der Giet M, Mischak H, Morgan M, Zidek W, Jankowski J, Dinucleoside polyphosphates: strong endogenous agonists of the purinergic system, Br J Pharmacol 157(7) (2009) 1142–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jankowski V, Tolle M, Vanholder R, Schonfelder G, van der Giet M, Henning L, Schluter H, Paul M, Zidek W, Jankowski J, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate: a novel endothelium- derived vasoconstrictive factor, Nat Med 11(2) (2005) 223–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jankowski V, Schulz A, Kretschmer A, Mischak H, Boehringer F, van der Giet M, Janke D, Schuchardt M, Herwig R, Zidek W, Jankowski J, The enzymatic activity of the VEGFR2 receptor for the biosynthesis of dinucleoside polyphosphates, J Mol Med (Berl) 91(9) (2013) 1095–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Matsumoto T, Tostes RC, Webb RC, The role of uridine adenosine tetraphosphate in the vascular system, Adv Pharmacol Sci 2011 (2011) 435132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhou Z, Sun C, Tilley SL, Mustafa SJ, Mechanisms underlying uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced vascular contraction in mouse aorta: Role of thromboxane and purinergic receptors, Vascul Pharmacol 73 (2015) 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Teng B, Labazi H, Sun C, Yang Y, Zeng X, Mustafa SJ, Zhou Z, Divergent coronary flow responses to uridine adenosine tetraphosphate in atherosclerotic ApoE knockout mice, Purinergic Signal 13(4) (2017) 591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jankowski V, Meyer AA, Schlattmann P, Gui Y, Zheng XL, Stamcou I, Radtke K, Tran TN, van der Giet M, Tolle M, Zidek W, Jankowski J, Increased uridine adenosine tetraphosphate concentrations in plasma of juvenile hypertensives, Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(8) (2007) 1776–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhou Z, Merkus D, Cheng C, Duckers HJ, Jan Danser AH, Duncker DJ, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate is a novel vasodilator in the coronary microcirculation which acts through purinergic P1 but not P2 receptors, Pharmacol Res 67(1) (2013) 10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hansen PB, Hristovska A, Wolff H, Vanhoutte P, Jensen BL, Bie P, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate affects contractility of mouse aorta and decreases blood pressure in conscious rats and mice, Acta Physiol (Oxf) 200(2) (2010) 171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhou Z, Chrifi I, Xu Y, Pernow J, Duncker DJ, Merkus D, Cheng C, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate acts as a proangiogenic factor in vitro through purinergic P2Y receptors, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 311(1) (2016) H299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gui Y, He G, Walsh MP, Zheng XL, Signaling mechanisms mediating uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced proliferation of human vascular smooth muscle cells, J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 58(6) (2011) 654–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wiedon A, Tolle M, Bastine J, Schuchardt M, Huang T, Jankowski V, Jankowski J, Zidek W, van der Giet M, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A) is a strong inductor of smooth muscle cell migration via activation of the P2Y2 receptor and cross-communication to the PDGF receptor, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 417(3) (2012) 1035–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schuchardt M, Tolle M, Prufer J, Prufer N, Huang T, Jankowski V, Jankowski J, Zidek W, van der Giet M, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate activation of the purinergic receptor P2Y enhances in vitro vascular calcification, Kidney Int 81(3) (2012) 256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Matsumoto T, Tostes RC, Webb RC, Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced contraction is increased in renal but not pulmonary arteries from DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301(2) (2011) H409–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Matsumoto T, Tostes RC, Webb RC, Alterations in vasoconstrictor responses to the endothelium-derived contracting factor uridine adenosine tetraphosphate are region specific in DOCA-salt hypertensive rats, Pharmacol Res 65(1) (2012) 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhou Z, Yadav VR, Sun C, Teng B, Mustafa JS, Impaired Aortic Contractility to Uridine Adenosine Tetraphosphate in Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertensive Mice: Receptor Desensitization?, Am J Hypertens (2017) 304–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhou Z, Lankhuizen IM, van Beusekom HM, Cheng C, Duncker DJ, Merkus D, Uridine Adenosine Tetraphosphate-Induced Coronary Relaxation Is Blunted in Swine With Pressure Overload: A Role for Vasoconstrictor Prostanoids, Front Pharmacol 9 (2018) 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Matsumoto T, Watanabe S, Kawamura R, Taguchi K, Kobayashi T, Enhanced uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced contraction in renal artery from type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats due to activated cyclooxygenase/thromboxane receptor axis, Pflugers Arch 466(2) (2014) 331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Matsumoto T, Watanabe S, Ando M, Yamada K, Iguchi M, Taguchi K, Kobayashi T, Diabetes and Age-Related Differences in Vascular Function of Renal Artery: Possible Involvement of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Rejuvenation Res 19(1) (2016) 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhou Z, Sorop O, de Beer VJ, Heinonen I, Cheng C, Jan Danser AH, Duncker DJ, Merkus D, Altered purinergic signaling in uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced coronary relaxation in swine with metabolic derangement, Purinergic Signal (2017) 319–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]