Abstract

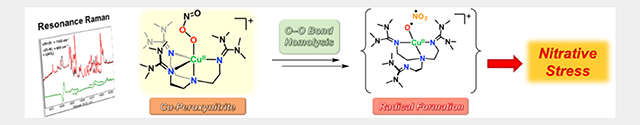

We report the formation of a new copper peroxynitrite (PN) complex [CuII(TMG3tren)(κ1-OONO)]+ (PN1) from reaction of [CuII(TMG3tren)(O2•–)]+ (1) with NO•(g) at –125 ºC. The first resonance Raman spectroscopic characterization of such a metal bound PN moiety supports a cis κ1-OONO– geometry. PN1 transforms thermally to an isomeric form (PN2) with κ2-O,O’-(–OONO) coordination, which undergoes O–O bond homolysis to generate a putative cupryl (LCuII–O•) intermediate and NO2•. These transient species do not recombine to give a nitrato (NO3–) product but instead proceed to effect oxidative chemistry and formation of a Cu(II)-nitrito (NO2–) complex (2).

Keywords: Bioinorganic Chemistry, Copper, Nitrogen Oxides, Raman Spectroscopy, Peroxynitrite

Graphical Abstract

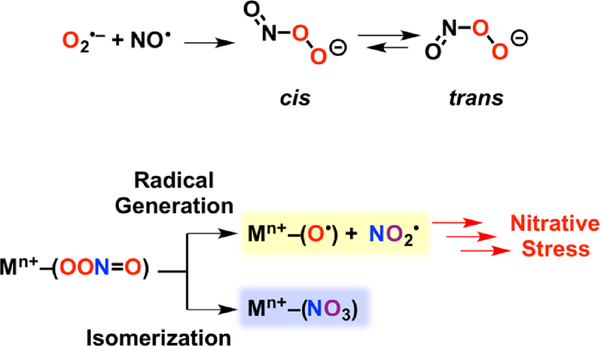

Nitric oxide (NO•) is an essential molecule in biology due to its role as a signaling agent,[1–3] its utilization in the human immune response,[4–6] and as an obligatory intermediate in the geobiochemical nitrogen cycle.[7,8] At elevated concentrations (μM) NO• is toxic[4,9–12] and its downstream derivatives can lead to oxidation and nitration of proteins[13–15], lipids[16,17] and nucleic acids.[18,19] Phagocytes leverage the toxicity of nitric oxide in combination with other reactive nitrogen and oxygen species (such as O2•–, H2O2 and NO2–) as tools to combat invading microorganisms.[5,6] Phagocytes also employ metal toxicity, and in particular copper, as a bactericide, but the synergy between destructive reactive nitrogen and oxygen species and copper burst in the macrophage remains largely unknown.[6,20–22] A key intermediate postulated to be responsible for nitric oxide’s toxicity is peroxynitrite (–OONO, PN), which may be derived from NO• and O2•– (Scheme 1).[23–25] Peroxynitrite can exist in two isomers, cis, or trans, and upon protonation, or in the presence of CO2, yield either nitrate, or freely diffusing radicals such as NO2•, HO•, and CO3•–.[10,26] Studies of aqueous peroxynitrite have deduced that the predominant decay pathway is isomerization to nitrate.[27,28]

Scheme 1.

Formation of Peroxynitrite from Superoxide and Nitric Oxide, and Mechanisms of Peroxynitrite Decomposition through Metal Ion Coordination.

Metal coordinated peroxynitrites are of interest due to the intimate role metals play in the regulation and processing of both NO• and O2•–,[3,29–32] which may implicate metals as important factors in the physiological formation and transformations of peroxynitrite (Scheme 1). While progress has been made to implicate metal ions in the decay of peroxynitrite, a discrete peroxynitrite coordination complex is rarely observed.[33–42] Examples of stable peroxynitrite complexes are scarce[43,44], and those containing vibrational (i.e., IR spectroscopic) information about the peroxynitrite ligand even more so.[45–48]

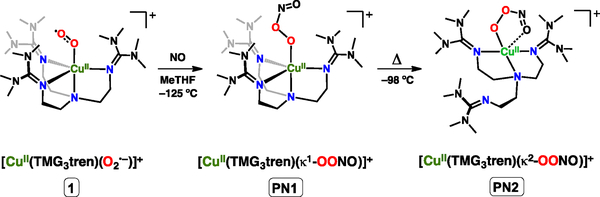

In a previous report we have described the formation of a cupric-peroxynitrite complex from the addition of NO• to [CuII(TMG3tren)(O2•–)]+ (1) at –80 ºC to generate the cupric-peroxynitrito complex [CuII(TMG3tren)(κ2-O,O’-OONO)]+ (PN2) (Scheme 2).[49] Direct vibrational evidence of this peroxynitrite complex was unable to be obtained, and information concerning the structural identity was derived from EPR spectroscopy and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Herein we report the formation of a new peroxynitrite complex, [CuII(TMG3tren)(κ1-OONO)]+ (PN1) formed prior to PN2, and the resonance Raman (RR) spectroscopic characterization of PN1 which to our knowledge is the first RR characterization of a metal-peroxynitrite species.

Scheme 2.

Generation of PN1 from addition of NO to complex 1. Thermal transformation of PN1 leads to formation of PN2.

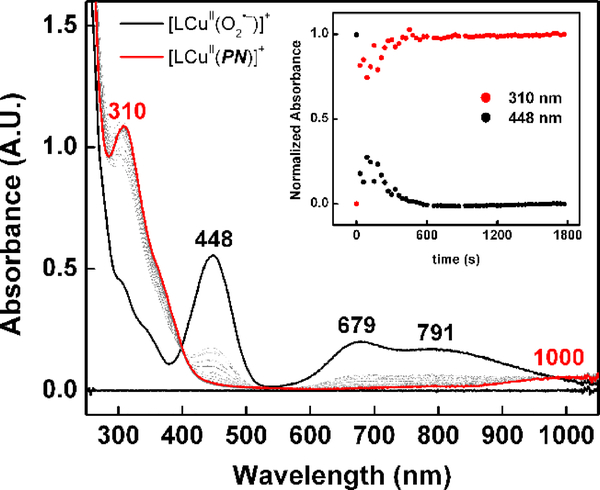

The complex PN1 is generated from the addition of NO• solubilized in 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (NO(MeTHF), see SI), to 1 at –125 ºC (Scheme 2). Monitoring the reaction by UV-vis spectroscopy reveals the gradual decrease of the cupric-superoxide features at 448, 679 and 791 nm and accompanied by the appearance of a new intense electronic transition at 310 nm (7300 M−1 cm−1) and a weak d-d transition at 1000 nm (~410 M−1 cm−1) (Figure 1). The intense high-energy feature near 310 nm has been has been reported for alkali and ammonium salts[50,51] and in metal coordination complexes of peroxynitrite.[43,45]

Figure 1.

Addition of NO(MeTHF) (7 equiv) to 1 (0.15 mM) in MeTHF at –125 ºC (black); full conversion to PN1 was observed within 30 minutes (red).

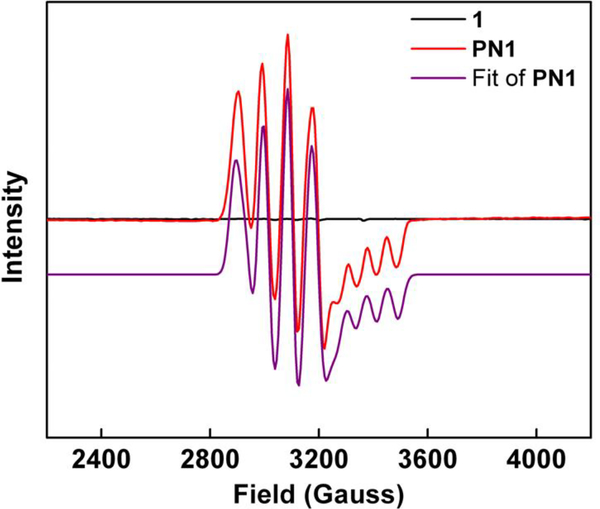

Formation of PN1 is easily monitored via EPR spectroscopy. Addition of NO(MeTHF) to the EPR silent 1 leads to the generation of an active EPR signal (Figure 2), consistent with the radical coupling of 1 (S = 1)[52] with NO• (S = ½) to give a S = ½ complex. A quantitative analysis of the EPR data through a Job’s plot shows maximal PN1 formation at a 1:1 mole ratio of Cu to NO•, confirming the 1:1 cupric-superoxide to NO stoichiometry (Figure S1).

Figure 2.

X-band EPR spectra of 1 (black, EPR silent), PN1 (red, 0.41 mM ) and fitted PN1 spectra (purple; g1–3 = 1.9874, 2.1945, 2.2040; A1–2 = 77.2 G, 111.3 G)

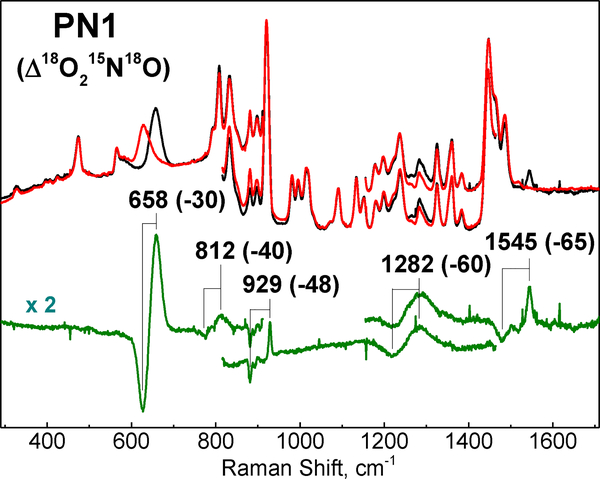

The RR spectra of PN1 reveal multiple isotopically sensitive features assigned to stretching and bending modes of the cupric-peroxynitrite complex (Figure 3). The feature with the highest intensity is at 658 cm–1 and shows a 30 cm−1 downshift with full labeling of the peroxynitrite ligand (i.e., 18O18O15N18O). This RR signal is unusually broad with a 29 cm−1 full width at half maximum (FWHM), and is reminiscent of the broad 642 cm−1 band observed in the Raman spectrum of the cis peroxynitrite anion in aqueous solution.[53,54] Labeling with 18O2 or 15N18O shifts the 658 cm−1 band –26 and –9 cm−1 respectively, supporting significant O–N stretching character to this mode which was otherwise assigned to an out of plane deformation in the free ion (Table 1 and Figure S2). Indeed, the observed shifts match well calculated shifts based on Hooke’s law for an O–N oscillator (–29.5 cm−1 with 18O–15N, –17 cm−1 with 18O–N, and –12 cm−1 with O–15N). The DFT vibrational analysis also supports a mode description that combines O–N stretch with O-ON=O bending (see below).

Figure 3.

RR spectra of PN1 (407 nm excitation) generated from O2 and 14N16O (black) or 18O2, 15N18O (red). Difference spectrum (unlabeled – labeled) is shown in green.

Table 1.

Summary of Isotopically Sensitive Vibrations of PN1; observed RR frequencies in cm−1 (isotope shift, cm−1), and calculated frequencies for cis and trans conformers (italicized numbers).

| Head 1 | OONO | 18O215N18O | 18O2NO | OO15N18O |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ν(O–N) +δ(NO2) | 658 | 628 (−30) | 637 (−21) | 647 (−11) |

| cis | 708 | (−35) | (−26) | (−9) |

| trans | 845 | (−45) | (−35) | (−12) |

| ν(O–O) +δ(NO2) | 812 | 772 (−40) | --- | --- |

| cis | 833 | (−45) | (−37) | (−14) |

| trans | 630 | (−35) | (−23) | (−15) |

| ν(O–O) +δ(NO2) | 929 | 881 (−48) | 900 (−29) | 912 (−17) |

| cis | 970 | (−53) | (−35) | (−16) |

| trans | 1002 | (−51) | (−35) | (−15) |

| ν(N=O) | 1545 | 1480 (−65) | 1543 (−2) | 1482 (−43) |

| cis | 1601 | (−68) | (−2) | (−68) |

| trans | 1627 | (−74) | (−3) | (−72) |

A much weaker and sharper band at 1545 cm–1 band is readily assigned to the peroxynitrite ν(N=O) stretch based on its frequency and large downshift with 15N18O (–65 cm–1) (Figure 3). This assignment is further strengthened by the limited sensitivity of this mode to the labeling of O2 (Δ18O2 = –2 cm–1) (Table 1 and Figure S3).

A band at 929 cm–1 strongly impacted by O2 labeling (Δ18O2 = –29 cm–1) as well as NO labeling (Δ15N18O = –17 cm–1) is assigned to an O–O stretch mixed with an O-N=O bend (Table 1 and Figure S4). A very weak band at 812 cm–1, which can be extracted from the MeTHF Raman spectrum background only after labeling of both O2 and NO, is tentatively assigned to another mixed vibrational mode that combines O–O stretch with in plane OO-N=O deformation. Finally, a broad signal at 1282 cm–1 that shifts –60 cm−1 after full labeling of the peroxynitrito group and that shows a moderate intensity relative to the fundamental mode at 658 cm−1 is likely to correspond to its first overtone.[55]

To aid interpretation of the RR data, predicted structures for PN1 were obtained via DFT calculations. The reverse axial copper EPR signal (Figure 2) is indicative of a trigonal bipyramidal copper geometry. Based on that constraint two possible structures were calculated, where the peroxynitrite ligand in either a cis or trans confirmation (Figures S5 & S6). The cis cupric-peroxynitrite isomer is predicted to be the more stable isomer by 4.1 kcal/mol, in line with previously reported calculations of the anion where the cis isomer is more stable by 3 kcal/mol.[53] The calculated Raman spectra provide satisfactory match with the experimental data, with the most highly Raman-active vibration observed in the mid-frequency range with significant O–N stretching character (Figures S7–S9). Calculated frequencies for this mode are 708 cm–1 in the cis-PN and 845 cm–1 in the trans-PN conformer, the former matching better with the 658 cm−1 observed frequency. Similarly, the calculated frequencies for modes dominated by ν(O–O) and ν(N=O) for the cis-PN are better match than that of the trans-PN (Table 1). In fact, the four fundamental Raman frequencies observed in PN1 are reproduced in the calculated spectrum of cis-PN with overestimations ranging from 0.02 to 0.08 typical of DFT calculations. Thus, the RR data support a cis geometry for the peroxynitrite ligand in PN1, as depicted in Scheme 2.

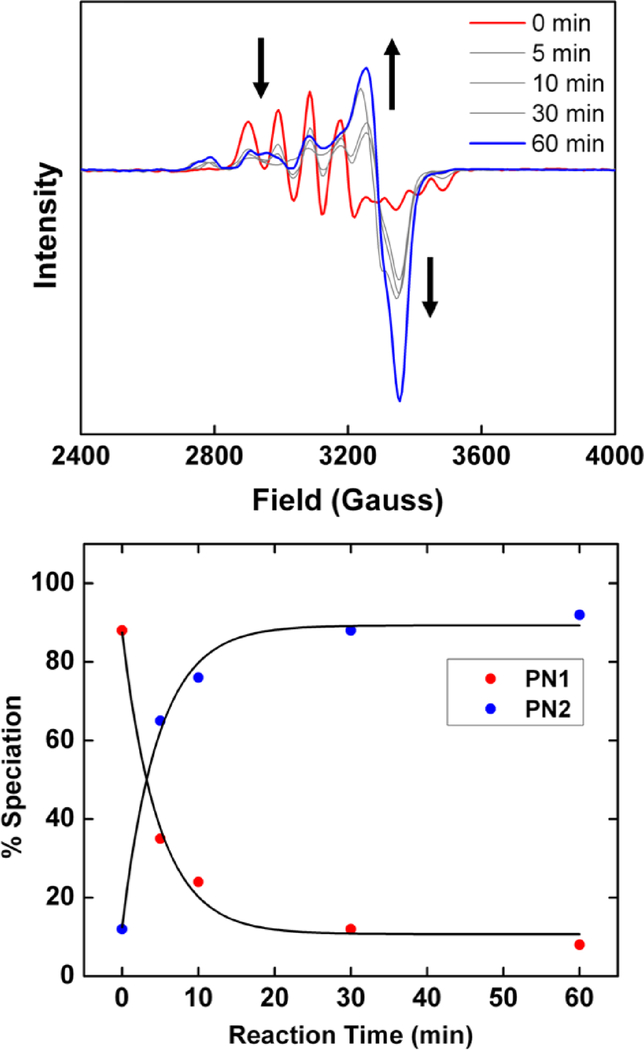

When NO• is added to 1 at –80 ºC a chelating peroxynitrite intermediate [CuII(TMG3tren)(κ2-O,O’-OONO)]+ (PN2) is formed, giving an axial EPR spectrum;[49] as described above, PN1 is formed at –125 ºC exhibiting a reverse axial copper geometry (Figure S10). If NO• is added at an intermediate temperature (–98 ºC) PN1 is observed as the initial species followed by conversion to PN2. The conversion from reverse axial to axial EPR signal (Figure 4) reflects a change in the copper center geometry from trigonal bipyramidal to square pyramidal. Such a change results in the deligation one of the tetramethylguanidine (TMG) arms which allows for the adaptation of a square pyramidal geometry.[49] Careful analysis of the EPR spectra after 60 minutes reveal the presence of two axial Cu signals (Figure 4) which is assigned to the partial decomposition of PN2 to the final Cu-nitrito product (see below).

Figure 4.

(Top) Conversion of PN1 (red) to PN2 (blue) at –98 ºC (see Figure S10 for fitted EPR parameters of PN2). (Bottom) Speciation of PN1 and PN2 (calculated via EasySpin, Figure S27) as a function of time and fit to a single exponential. Conversion of 90% of PN1 to PN2 occurs within 30 minutes.

Attempts to obtain RR spectra from PN2 were inconclusive. Gradual photo-bleaching of PN1 was observed during the acquisition of the Raman spectra and presumably PN2 exhibits a greater photosensitivity.

Upon further warming to –60 ºC, PN2 decays to a chelating copper nitrito species [CuII(TMG3tren)(κ2-O,O’-NO2)]+ (2) confirmed by ESI–MS (Figure S11). EPR spectroscopy (Figure S12) indicates the copper maintains a tetragonal coordination geometry, thus also with one deligated ligand arm, as confirmed by comparison of UV-vis and EPR properties with a square-pyramidal CuII-NO2− analogue with tridentate ligand, [CuII(TMG2dien)k2-O,O’-NO2−)]+ (X-ray structure, UV-vis & EPR properties have also been determined; Figures S13 and S14). UV-vis quantification puts the yield of 2 at 95 ± 4% (Figure S15), and the presence of nitrite was independently quantified via a Griess assay was found to be in good yield (75 ± 2 %) (Figure S16 & Table S1). The kinetics of PN2 transformation to CuII-NO2 species 2 indicated overall first order in Cu behavior (Figure S17) consistent with unimolecular decay, most likely though cleavage of the O–O bond. This result rules against higher order copper adducts participating in peroxynitrite decay as suggested in the aqueous H+ and CO2 mediated decay pathways.[27,28]

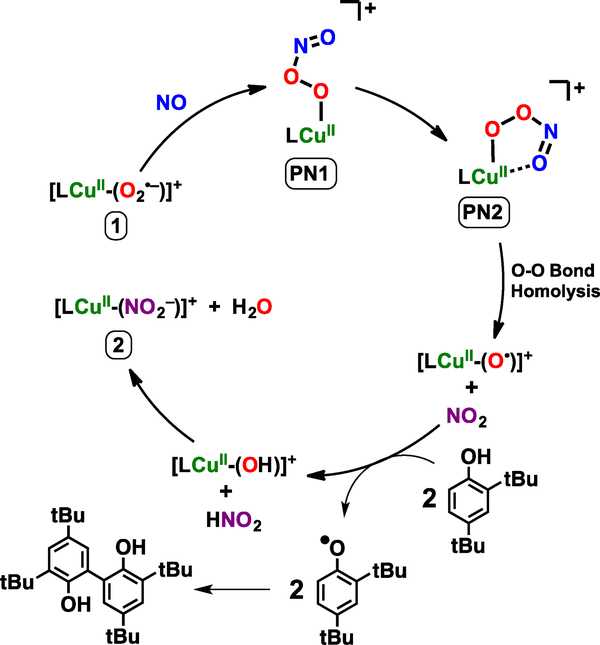

The detection and characterization (see SI) of a high yield cupric-nitrite (NO2–) product from PN2 thermal transformation is consistent with the formation of cupryl [CuII(TMG3tren)(O•)]+ and NO2• intermediates following peroxynitrite homolytic O–O bond cleavage; the most common recombination of such radicals to give a Cu-nitrate product does not occur (Scheme 1). In the absence of substrate we postulate the putative cupryl intermediate goes on to hydroxylate the solvent via a radical rebound pathway to give LCuI and R–OH (R = solvent) before LCuI reacts with NO2• to yield LCuII–(NO2–) as the final product (Scheme S1).[36,44,46,56,57] To verify the generation of these radical species, addition of >500 equiv excess of 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (DTBP) results in the nearly quantitative formation of both 2 and the coupled bis-phenol product, 3,3’,5,5’-tetra-tert-butyl-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2,2’-diol (Figures S18 & S19). The coupling of phenoxyl species to give the observed diol can be rationalized by successive hydrogen atom abstractions by LCuII–O• and NO2• (a strong oxidant[58,59]) to give LCuII–OH and HNO2 before ligand exchange to give LCuII–NO2 and H2O (Scheme 3). A concerted O–O bond cleavage / O–H bond activation pathway is also plausible; further mechanistic studies will be required to differentiate between stepwise and concerted substrate oxidation. Additional experiments using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO, 500 equiv), a known radical trapping agent used to probe O–O bond scission reactions,[60,61] resulted in detection of LCuII(O–DMPO) by ESI-MS (Figure S20) following warming of the reaction mixture. These results are consistent with the generation of two equivalents of oxidant per equivalent of copper-peroxynitrite, the two species deriving from O-O bond cleavage.

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol oxidation and CuII-NO2− production via PN2 thermal transformation.

In summary, we have described the synthesis and preparation of the first transition metal-peroxynitrite complex characterized by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Comparison with Raman data from alkylammonium cis-peroxynitrite, combined with analytical Raman calculations have suggested the peroxynitrito ligand is coordinated to copper in a cis-geometry. Thermal transformation of this peroxynitrite complex leads to O–O homolysis and the generation of LCu–O• and NO2• which go on to perform further oxidative chemistry. These results further underscore the importance of understanding the biological role transition metal ions may play in biochemical oxidative and nitrative damage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (GM28962 to K.D.K. and GM074785 to P.M.-L.). J.J.L. thanks the Zeltmann family for the Eugene W. and Susan C. Zeltmann fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1].Ignarro LJ, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 1990, 30, 535–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ignarro LJ, Nitric Oxide as a Communication Signal in Vascular and Neuronal Cells, Academic Press, San Diego, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Tennyson AG, Lippard SJ, Chem. Biol 2011, 18, 1211–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Toledo JC, Augusto O, Chem. Res. Toxicol 2012, 25, 975–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hu K, Li Y, Rotenberg SA, Amatore C, Mirkin MV, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 4564–4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dalecki AG, Crawford CL, Wolschendorf F, in Adv. Microb. Physiol. (Ed.: Poole RK), Elsevier Ltd, Oxford, UK, 2017, pp. 193–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lehnert N, Dong HT, Harland JB, Hunt AP, White CJ, Nat. Rev. Chem 2018, 2, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lancaster KM, Caranto JD, Majer SH, Smith MA, Joule 2018, 2, 421–441. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L, Physiol. Rev 2007, 87, 315–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ferrer-Sueta G, Campolo N, Trujillo M, Bartesaghi S, Carballal S, Romero N, Alvarez B, Radi R, Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 1338–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Radi R, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 5839–5848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Li Y, Hu K, Yu Y, Rotenberg SA, Amatore C, Mirkin MV, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 13055–13062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ischiropoulos H, Zhu L, Chen J, Tsai M, Martin JC, Smith CD, Beckman JS, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1992, 298, 431–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Demicheli V, Moreno DM, Jara GE, Lima A, Carballal S, Ríos N, Batthyany C, Ferrer-Sueta G, Quijano C, Estrĺn DA, et al. , Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3403–3417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ye H, Li H, Gao Z, Chem. Res. Toxicol 2018, 31, 904–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jain K, Siddam A, Marathi A, Roy U, Falck JR, Balazy M, Free Radic. Biol. Med 2008, 45, 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Davies SS, Guo L, in Mol. Basis Oxidative Stress, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013, pp. 49–70. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fujii S, Sawa T, Ihara H, Tong KI, Ida T, Okamoto T, Ahtesham AK, Ishima Y, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M, et al. , J. Biol. Chem 2010, 285, 23970–23984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ahmed KA, Sawa T, Ihara H, Kasamatsu S, Yoshitake J, Rahaman MM, Okamoto T, Fujii S, Akaike T, Biochem. J 2012, 441, 719–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].White C, Lee J, Kambe T, Fritsche K, Petris MJ, J. Biol. Chem 2009, 284, 33949–33956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Achard MES, Stafford SL, Bokil NJ, Chartres J, Bernhardt PV, Schembri MA, Sweet MJ, McEwan AG, Biochem. J 2012, 444, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fu Y, Chang F-MJ, Giedroc DP, Acc. Chem. Res 2014, 47, 3605–3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Beckman JS, in Nitric Oxide Princ. Actions (Ed.: Lancaster JJ), Academic Press, Inc, San Diego, 1996, pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Blough NV, Zafiriou OC, Inorg. Chem 1985, 24, 3502–3504. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bohle DS, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 1998, 2, 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Goldstein S, Merényi G, in Methods Enzymol, 2008, pp. 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Molina C, Kissner R, Koppenol WH, Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 9898–9905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Serrano-Luginbuehl S, Kissner R, Koppenol WH, Chem. Res. Toxicol 2018, 31, 721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sheng Y, Abreu IA, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ, Miller AF, Teixeira M, Valentine JS, Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 3854–3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Herold S, Koppenol WH, Coord. Chem. Rev 2005, 249, 499–506. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schopfer MP, Wang J, Karlin KD, Inorg. Chem 2010, 49, 6267–6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Su J, Groves JT, Inorg. Chem 2010, 49, 6317–6329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Koebke KJ, Pauly DJ, Lerner L, Liu X, Pacheco AA, Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 7623–7632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gogoi K, Saha S, Mondal B, Deka H, Ghosh S, Mondal B, Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 14438–14445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yokoyama A, Cho K-B, Karlin KD, Nam W, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 14900–14903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kumar P, Lee Y, Hu L, Chen JJ, Jun Y, Yao J, Chen H, Karlin KD, Nam W, Park YJ, et al. , J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 7753–7762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hong S, Kumar P, Bin Cho K, Lee YM, Karlin KD, Nam W, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2016, 55, 12403–12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kurtikyan TS, Ford PC, Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 8570–8572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schopfer MP, Mondal B, Lee D, Sarjeant AAN, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 11304–11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Kalita A, Kumar P, Mondal B, Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 4636–4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kalita A, Deka RC, Mondal B, Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 10897–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mondal B, Saha S, Borah D, Mazumdar R, Mondal B, Inorg. Chem 2019, 58, 1234–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Park GY, Deepalatha S, Puiu SC, Lee D-H, Mondal B, Narducci Sarjeant AA, del Rio D, Pau MYM, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2009, 14, 1301–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sharma SK, Schaefer AW, Lim H, Matsumura H, Moënne-Loccoz P, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Solomon EI, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 17421–17430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wick PK, Kissner R, Koppenol WH, Helv. Chim. Acta 2000, 83, 748–754. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kurtikyan TS, Eksuzyan SR, Hayrapetyan VA, Martirosyan GG, Hovhannisyan GS, Goodwin JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 13861–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kurtikyan TS, Eksuzyan SR, Goodwin JA, Hovhannisyan GS, Inorg. Chem 2013, 52, 12046–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Cao R, Elrod LT, Lehane RL, Kim E, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 16148–16158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Maiti D, Lee D-H, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Pau MYM, Solomon EI, Gaoutchenova K, Sundermeyer J, Karlin KD, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 6700–6701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bohle DS, Glassbrenner PA, Hansert B, in Methods Enzymol, 1996, pp. 302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lo W, Lee Y, Tsai JM, Beckman S, Chem. Phys. Lett 1995, 242, 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Woertink JS, Tian L, Maiti D, Lucas HR, Himes R. a, Karlin KD, Neese F, Würtele C, Holthausen MC, Bill E, et al. , Inorg. Chem 2010, 49, 9450–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tsai JM, Harrison JJG, Martin JC, Hamilton TP, Van Der Woerd M, Jablonsky MJ, Beckman JS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1994, 116, 4115–4116. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tsai H, Hamilton TP, Tsai JM, Van Der Woerd M, Harrison JG, Jablonsky MJ, Beckman JS, Koppenol WH, J. Phys. Chem 1996, 100, 15087–15095. [Google Scholar]

- [55]. Calculating the anharmonicity constant based on these two observed Raman frequencies leads to a frequency corrected for anharmonicity of 692 cm–1 well matched by the DFT frequency calculations for the cis-PN1 optimized geometry.

- [56].Kalita A, Kumar P, Mondal B, Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 4636–4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Unlike a previous report using the same system where a putative cupryl (generated via O2 and H-atom donor or directly via an O-atom donor) performs intramolecular hydroxylation,[62] no such reaction takes place in the present study as evidenced by ESI-MS.

- [58].Wilmarth WK, Stanbury DM, Byrd JE, Po HN, Chua C, Coord. Chem. Rev 1983, 51, 155–179. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Koppenol WH, Moreno JJ, Pryor WA, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS, Chem. Res. Toxicol 1992, 5, 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Kunishita A, Ishimaru H, Nakashima S, Ogura T, Itoh S, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 4244–4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Iovan DA, Wrobel AT, McClelland AA, Scharf AB, Edouard GA, Betley TA, Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 10306–10309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Maiti D, Lee D-H, Gaoutchenova K, Würtele C, Holthausen MC, Narducci Sarjeant AA, Sundermeyer J, Schindler S, Karlin KD, Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2008, 47, 82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.