Abstract

The APETALA1 (AP1)/FRUITFULL (FUL)-like transcription factor OsMADS18 plays diverse functions in rice development, but the underlying molecular mechanisms are far from fully understood. Here, we report that down-regulation of OsMADS18 expression in RNAi lines caused a delay in seed germination and young seedling growth, whereas the overexpression of OsMADS18 produced plants with fewer tillers. In targeted OsMADS18 genome-edited mutants (osmads18-cas9), an increased number of tillers, altered panicle size, and reduced seed setting were observed. The EYFP-OsMADS18 (full-length) protein was localized to the nucleus and plasma membrane but the EYFP-OsMADS18-N (N-terminus) protein mainly localized to the nucleus. The expression of OsMADS18 could be stimulated by abscisic acid (ABA), and ABA stimulation triggered the cleavage of HA-OsMADS18 and the translocation of OsMADS18 from the plasma membrane to the nucleus. The inhibitory effect of ABA on seedling growth was less effective in the OsMADS18-overexpressing plants. The expression of a set of ABA-responsive genes was significantly reduced in the overexpressing plants. The phenotypes of transgenic plants expressing EYFP-OsMADS18-N resembled those observed in the osmads18-cas9 mutants. Analysis of the interaction of OsMADS18 with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS57 strongly suggests an essential role for OsMADS18 in rice development.

Keywords: ABA, MADS-box, membrane-bound transcription factor, plant architecture, rice, tiller

OsMADS18 plays an essential role in rice development, including seed maturation and germination, tiller formation, and the response to ABA

Introduction

The MADS-box transcription factors represent one of the best-known gene families and play critical roles in plant development. MADS is an acronym referring to the first four members of the family to be identified: MINICHROMOSOME MAINTENANCE 1 from the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, AGAMOUS from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), DEFICIENS from snapdragon (Antirrhinum majus), and SERUM RESPONSE FACTOR from humans (Homo sapiens) (Smaczniak et al., 2012). Proteins in the MADS-box family contain a common DNA-binding domain (the MADS domain) and recognize DNA sequences such as CC[A/T]6GG, termed the CArG box. The MADS-box genes are believed to be involved in almost all organ morphogenesis processes throughout the plant life cycle (Smaczniak et al., 2012; Schilling et al., 2018).

In rice (Oryza sativa), OsMADS18 and its two paralogs, OsMADS14 and OsMADS15, have been phylogenetically classified into the AP1/FUL-like group of MADS-box family proteins (Masiero et al., 2002). OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 are classified as a pair of sister subclasses, while OsMADS18 is considered to be a relatively distant subclass (Litt and Irish, 2003; Yamaguchi and Hirano, 2006). Although the overexpression of OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS18 promotes flowering in rice (Jeon et al., 2000; Fornara et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2012), OsMADS18 is believed to have additional functions in development (Yamaguchi and Hirano, 2006). The expression pattern of OsMADS18 is very different from that of OsMADS14 or OsMADS15, which are largely detected in the floral meristem, glume primordia, lemma, palea, and lodicules (Callens et al., 2018). OsMADS18 is expressed in most tissues, including the roots, leaves, inflorescences, and flowers, and its expression has been shown to increase during rice reproduction (Masiero et al., 2002; Fornara et al., 2004). Along with OsMADS18, OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 are involved in specifying the inflorescence meristem identity through interaction with PANICLE PHYTOMER 2 (PAP2/OsMADS34), another MADS-box member that belonging to a grass-specific subclade of the SEPALLATA subfamily (Kobayashi et al., 2012). A recent study revealed that the AP1/FUL-like genes are recruited for a homeotic (A)-function in the grasses and some eudicots, and that OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 are required to specify the palea and lodicule identities (Wu et al., 2017).

Plant architecture is important for crop growth and productivity. Favorable architectural traits confer greater yields of products such as seeds and fruits (Wang et al., 2018). The ideal rice architecture is characterized by a low number of tillers, few of which are unproductive tillers, more grains per panicle, and thick and sturdy stems (Khush, 1995). Several genes controlling plant architecture have been identified in rice. DWARF14 (D14) encodes an α/β hydrolase that functions as a strigolactone (SL) receptor to negatively regulate rice branching; the d14 mutant displays increased shoot branching and a decreased plant height (Arite et al., 2009; Yao et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2018). TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1 (OsTB1), also known as FINE CULM 1 (FC1), inhibits the outgrowth of rice axillary buds by modulating the signal transduction of SL (Takeda et al., 2003), while IDEAL PLANT ARCHITECTURE 1 (IPA1), one of the transcription factors in the SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE family, plays an important role in the determination of plant architecture targeted by SL signaling (Jiao et al., 2010; Song et al., 2017). MONOCULM 1 (MOC1), a member of the GRAS (GAI, RGA, SCR) transcription factor family, has been identified as an important player in the control of tillering (Li et al., 2003); however, it can be targeted for degradation by the activity of TILLERING AND DWARF 1 (TAD1), a coactivator of the anaphase-promoting complex (Xu et al., 2012).

Most transcription factors are generally cytosolic and can be prevented from entering the nucleus by protein–protein interactions, restricting their ability to regulate transcription (Zupicich et al., 2001). It is believed that more than 10% of transcription factors in the whole genome of plants are membrane-tethered or membrane-bound, and the activation of membrane-bound transcription factors (MTFs) is important for adaptation to a stress condition (Seo et al., 2008). In general, the C-terminus of a MTF is crucial for its anchorage to the membrane (Seo et al., 2008). Upon responding to the abrupt environmental signals, the MTFs can be cleaved by a mechanism such as proteolytic cleavage or ubiquitination, then translocated to the nucleus to regulate the expression of their target genes (Vik and Rine, 2000; Chen et al., 2008; Seo et al., 2008; Slabaugh and Brandizzi, 2011; Zhou et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018).

In this study, we report that OsMADS18 plays an essential role in rice development. Down-regulation of OsMADS18 activity leads to delayed seed germination and retarded growth in young seedlings, while the overexpression of OsMADS18 results in altered plant architecture, including reduced numbers of tillers. When the function of OsMADS18 is completely blocked using targeted OsMADS18 genome editing, the resulting mutant plants produce more tillers, display delayed flowering, and have decreased seed setting. The membrane-bound and nuclear localization traits observed for OsMADS18 during different developmental stages implied its functional characteristics. OsMADS18 responds to abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, demonstrating its involvement in this pathway in rice. The interaction of OsMADS18 with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS57 suggests that OsMADS18 may function in various developmental stages of rice.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

All plants were in the Oryza sativa L. japonica cv. Nipponbare (Nip) background. Transgenic lines were generated via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, using the method described by Nishimura et al. (2006). In brief, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 was transformed and confirmed to be harboring the desired plasmid. Rice calli were induced from mature Nip seeds and transformed. The Agrobacterium-infected rice calli were selected by screening for resistance to hygromycin B (Phyto Technology, USA); resistant calli were transferred to N6D-S medium, and plantlets were regenerated on MS-NK medium (Nishimura et al., 2006).

The osmads18-cas9 mutants were generated by BioRun (http://www.biorun.net), using CRISPR/Cas9 targeted genome editing. Mutants were selected by screening for resistance to hygromycin B. The selected plants were either grown in a greenhouse with a 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod, at 24–32 °C, or outdoors from April to October in Wuhan, China.

Plasmid construction

To construct plasmids for generating transgenic lines, the binary vector pCAMBIA1300 (Addgene, https://www.addgene.org) containing a maize (Zea mays) ubiquitin promoter (Christensen and Quail, 1996) was used. To construct the plasmids pCAMBIA1300-OsMADS14, pCAMBIA1300-OsMADS15, and pCAMBIA1300-OsMADS18, the full-length coding sequences (CDS) of OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS18 were amplified from RNA extracted from young panicles of Nip by reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR). The confirmed PCR fragment of OsMADS14 (762 bp), OsMADS15 (804 bp), or OsMADS18 (750 bp) was cloned into pCAMBIA1300 at the cloning sites KpnI and SacI. Similarly, to construct the plasmids pCAMBIA1300-EYFP-OsMADS18, pCAMBIA1300-EYFP-OsMADS18-N, and pCAMBIA1300-OsMADS18-C, the fragment of EYFP-OsMADS18 (+1 bp to +750 bp), EYFP-OsMADS18-N (+1 bp to +513 bp), or OsMADS18-C (+172 bp to +249 bp) was cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300 at the cloning sites KpnI and SacI. The plasmid pCAMBIA1300-HA-OsMADS18 was constructed by fusing the full-length OsMADS18 fragment with a hemagglutinin (HA) tag, and cloning the fused cassette into pCAMBIA1300 at the cloning sites BamHI and SacI.

To generate RNA interference (RNAi) transgenic lines, the plasmid pCAMBIA1300-OsMADS18-RNAi was made by the method reported by Shen et al. (2018), with minor modifications. Briefly, two inverted 364 bp double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) fragments (from +440 bp to +813 bp of OsMADS18 CDS) were amplified by PCR using the primer pairs 18RNAiF and 18RNAiR. The dsRNAi cassette, containing two oppositely oriented sequences, was cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1300 at the cloning sites XhoI and XbaI.

The plasmid pCAMBIA1300-OsMADS18pro-GUS was constructed for producing a transgenic line expressing OsMADS18pro-GUS. The promoter sequence, 2.0 kb upstream of the start codon ATG, was amplified from the genomic DNA of Nip. The confirmed PCR fragment was fused with the fragment of the β-glucuronidase gene (GUS). The cassette OsMADS18pro-GUS was then inserted between the cloning sites HindIII and SacI in pCAMBIA1300.

For analyzing cellular localization using a transient expression assay, the plasmids p35S-EYFP-OsMADS14, p35S-EYFP-OsMADS15, p35S-EYFP-OsMADS18, p35S-EYFP-OsMADS18-N, and p35S-EYFP-OsMADS18-C were constructed, following the protocol described in previous reports from our laboratory (Wang et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2015). At the same time, the full-length CDS of OsPRA2 (a small G protein that is homologous with Pea Pra2 protein; 678 bp; Zhang et al., 2016) and DLT (DWARF AND LOW-TILLERING; 1854 bp; Tong et al., 2009) were amplified from cDNA of 45-day-old Nip seedlings and cloned into p35S-CFP (Lu et al., 2013) with EcoRI and BamHI to produce the constructs p35S-CFP-OsPRA2 and p35S-CFP-DLT, respectively.

For expressing recombinant proteins, the CDS of OsMADS14 (764 bp), OsMADS15 (804 bp), and OsMADS18 (750 bp) were respectively cloned into the pET28a vector (Novagen, USA) at the BamHI and SacI cloning sites. In addition, the OsMADS18 (750 bp) and OsMADS57 (729 bp) fragment were respectively inserted into the pGEX-4TI vector (GE Healthcare, USA) at the EcoRI and SacI cloning sites. For the bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay, the CDS of OsMADS14 (764 bp), OsMADS15 (804 bp), OsMADS18 (750 bp), and OsMADS57 (729 bp) were inserted into the vector p35S-YC-MCS or p35S-YN-MCS, following the protocol described by Lu et al. (2013). The primer sequences used for all plasmid constructions are listed in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online.

Histochemical analysis

The histochemical analysis for the expression of the GUS reporter in transgenic plants harboring OsMADS18pro-GUS followed the method described by Jefferson et al. (1987). Photographs were taken using a Nikon SMZ1500 dissection microscope (Nikon, Japan) or a Canon EOS 70D digital camera (Canon, Japan).

Seed germination

Only seeds kept under the same storage conditions for the same period of time were used for the seed germination assay. The peeled seeds were first surface-sterilized with 2% sodium hypochlorite and then kept overnight in sterilized distilled water at 37 °C. On the second day, the seeds were sown on Murashige and Skoog (MS; Murashige and Skoog, 1962) plates containing 3% sucrose and 0.8% (w/v) agar (Sigma, USA) and transferred to a growth chamber with a 14 h light/10 h dark photoperiod, at 30 °C. Coleoptile greening was then analyzed.

Hormone measurement

Leaves harvested from 45-day-old Nip plants were used for measurement of the content of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). The extraction and derivatization of IAA were performed as described previously (Li et al.,2015; Xiong et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019). Briefly, [2H5] IAA (15.0 ng g–1) was added to the samples as internal standard. The IAA contents were quantified using the microTOFq orthogonal-accelerated TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany).

Preparation and transformation of protoplasts

Protoplasts were isolated from 5-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings, 7-day-old Nip seedlings, or 35-day-old rice plants, by following the methods described previously (Zhang et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2013). For each transformation, 5–10 μg plasmid DNA was gently mixed with 100 μl protoplast suspension and 110 μl 40% polyethylene glycol 4000 (PEG4000; Sigma, USA) solution containing 0.4 M mannitol and 100 mM CaCl2. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min. To stop the reaction, 440 μl W5 solution (2 mM MES, pH 5.7, 154 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 125 mM CaCl2) was added. The protoplasts were collected by brief centrifugation and resuspended in W5 solution, and incubated at 23 °C in the dark.

Analysis of gene expression

Gene expression levels were assessed by quantitative RT–PCR (qRT–PCR). Total RNA in fully expanded fresh blades of rice was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were reverse-transcribed with ReverTra Ace-α-® (Toyobo, Japan). The cDNA was amplified using a SYBR Green master mixture (Applied Biosystems, USA) with a CFX connect real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, USA). The expression level of OsACTIN1 (Os03g0718100) was used as a loading control. The primer sequences used for the qRT–PCR experiments are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Cellular localization analysis

The plasmids p35S-EYFP-OsMADS14, p35S-EYFP-OsMADS15, p35S-EYFP-OsMADS18, p35S-EYFP-OsMADS18-N, and p35S-EYFP-OsMADS18-C were respectively transformed into protoplasts, and cellular localization was analyzed by methods described previously (Lu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2015). The fluorescent lipophilic cationic indocarbocyanine dye Dil (1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine; Beyotime, China) at a concentration of 20 mM was used to indicate the plasma membrane (Qian et al., 2014). Plasmid p35S-CFP-OsPRA2 was used as a marker for indicating plasma membrane localization and p35S-CFP-DLT for nuclear localization. DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma, USA) at a concentration of 0.29 mM was used for staining the nucleus.

ABA treatment

The ABA treatment was performed according to the method described by Tang et al. (2012). In brief, to measure the response to ABA of the expression level of OsMADS18, Nip seeds were germinated on MS plates for 2 days, and then the germinated seeds were transferred to half-strength liquid MS culture medium and grown for 8 days in a greenhouse. Then, 100 μM ABA [(±) abscisic acid; Sigma-Aldrich, USA] was added to the half-strength liquid MS culture medium, and the samples were harvested at 0, 3, 6, and 9 h. To examine ABA responsiveness, seeds were germinated on MS plates containing 3% sucrose and 0.8% (w/v) agar for 24 h and then transferred to MS plates containing 3% sucrose and 0.8% (w/v) agar with or without ABA. The shoot length was measured at day 9 after transfer. The control culture medium contained an equal amount of 100% ethanol, which was used for preparing the ABA stock solution.

Immunoblotting and protein pull-down assay

The accumulation of HA-OsMADS18 protein after ABA induction was analyzed by an immunoblotting assay. Blades from 35-day-old HA-OsMADS18 transgenic plants were treated with 100 μM ABA for 0, 3, 6, and 12 h. The blades were homogenized in extraction buffer containing 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM NaF, 0.5 mM Na3VO4, 15 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail, to prepare a total protein extract. An equal amount of protein from each treatment was subjected to the immunoblotting assay. The protein was separated in 12% SDS-PAGE gel, and anti-HA antibody (Abcam, USA) was used for detecting the HA-OsMADS18 protein. Total protein extracted from transgenic plants expressing empty vector pCAMBIA1300-HA was used as the control. As an internal control, anti-Actin antibody (ABclonal, China) was used to detect endogenous Actin protein.

Pull-down experiments were performed according to previously described methods Wang et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2015). Purified GST-OsMADS18 protein (using glutathione sepharose beads; GE Healthcare, USA) was incubated with purified His-OsMADS14 or His-OsMADS15 protein in binding buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA) overnight at 4 °C. Purified GST-OsMADS57 was incubated with His-OsMADS14, His-MADS15, or His-MADS18 protein in binding buffer. To remove unbound protein, the beads were collected by centrifugation at 700 g for 5 min and then washed five times with binding buffer. After washing, the collected protein pellet was separated in a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-His antibody (ABclonal, China).

Results

OsMADS18 modulates seed germination and tiller development

To elucidate the function of OsMADS18 in rice development, we qualitatively and quantitatively surveyed the expression of OsMADS18 in various tissues. OsMADS18 expression was barely detectable in mature seeds and germinated seedlings, and was not detected in plants less than 4 weeks old (Supplementary Fig. S1). A strong OsMADS18pro-GUS signal was observed in the internodes, stems, young panicles, florets, and pollinated ovaries of 75-day-old plants (Supplementary Fig. S1), consistent with previous reports (Masiero et al., 2002; Fornara et al., 2004). We generated transgenic rice lines overexpressing OsMADS18 or with down-regulated OsMADS18 expression (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Two overexpression (OE) lines (OE5 and OE8) with elevated OsMADS18 expression, and two RNAi lines (RNAi5 and RNAi6) with reduced levels of OsMADS18 expression, were selected for subsequent studies. We observed that seeds of the RNAi lines germinated much more slowly on MS plates than those of Nip and the OE lines (Fig. 1A, B); for instance, after 2 days of germination, over 95% of Nip and OE seeds had germinated and their green coleoptiles had emerged, while only up to 40% of the RNAi seeds had germinated. The root growth of the germinating OE seeds was smaller than that of Nip. The shoot growth of the RNAi lines was also smaller that of the Nip and OE plants (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S2B). To determine the reason for the differential germination behaviors among the seeds of the Nip, OE, and RNAi lines, we examined their grain quality, which revealed that the grains of the RNAi lines were severely chalked (Supplementary Fig. S2C, D). Chalky seeds commonly have germination problems (Zhang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). We hypothesized that the lower germination rate of the RNAi5 and RNAi6 seeds was caused by the reduced OsMADS18 expression in these lines.

Fig. 1.

OsMADS18 modulates seed germination and tiller development. (A) Delayed seed germination in the RNAi lines. Seeds were sown on MS plates. Photographs were taken on the second day of germination. Scale bar=5 mm. (B) Germination percentage. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>40 for each experiment). (C) Inhibition of auxiliary tiller growth observed in 45-day-old OE greenhouse-grown plants. Scale bar=1 cm. (D) The OE plants showed an earlier flowering phenotype. All plants were grown in natural conditions for 72 days. Scale bar=10 cm. (E) Tiller numbers in 72-day-old plants. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (F) Relative expression levels of a set of genes. RNAs were extracted from the blades of 45-day-old plants. OsACTIN1 expression was used as an internal control. The gene expression level in Nip was assigned a value of 1. Data represent the mean ±SD of three replicates. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (G) Endogenous IAA content (ng g–1 fresh weight) in the leaves of 45-day-old Nip and OE8 plants. Data represent the mean ±SD of three replicates. **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

We tracked the growth phenotypes of plants of the Nip, OE, and RNAi lines and noticed that the OE plants flowered early, had inhibited axillary bud growth, and produced remarkably fewer tillers than the Nip (Fig. 1C–E). To understand why the altered expression level of OsMADS18 affected tiller growth, we analyzed the expression profile of a set of tiller-related genes in 45-day-old Nip, OE, and RNAi plants. The expression level of D14 (Yao et al., 2016), the SL receptor gene, was reduced in OE8 plants but increased in RNAi6 plants, while the expression level of OsTB1 (Minakuchi et al., 2010), a SL signaling component, was markedly higher in the OE8 plants than in Nip and RNAi6 plants. The expression of the brassinosteroid repressor gene Homeobox protein knotted-1-like 1 (OSH1) (Tsuda et al., 2014; Singh and Savaldi-Goldstein, 2015) was significantly increased in the RNAi6 plants, but not altered in OE8, compared with that of Nip (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these data suggest that the altered tiller development in the OE plants is associated with changes in the expression of these tillering-related genes. Auxin homeostasis is essential for the growth of axillary buds in rice (Lu et al., 2015); therefore, we also measured the content of endogenous IAA in the Nip and OE plants. The IAA content in 45-day-old OE8 plants was significantly lower than that of Nip plants (Fig. 1G); this difference may have resulted in the differences in axillary bud growth between these lines.

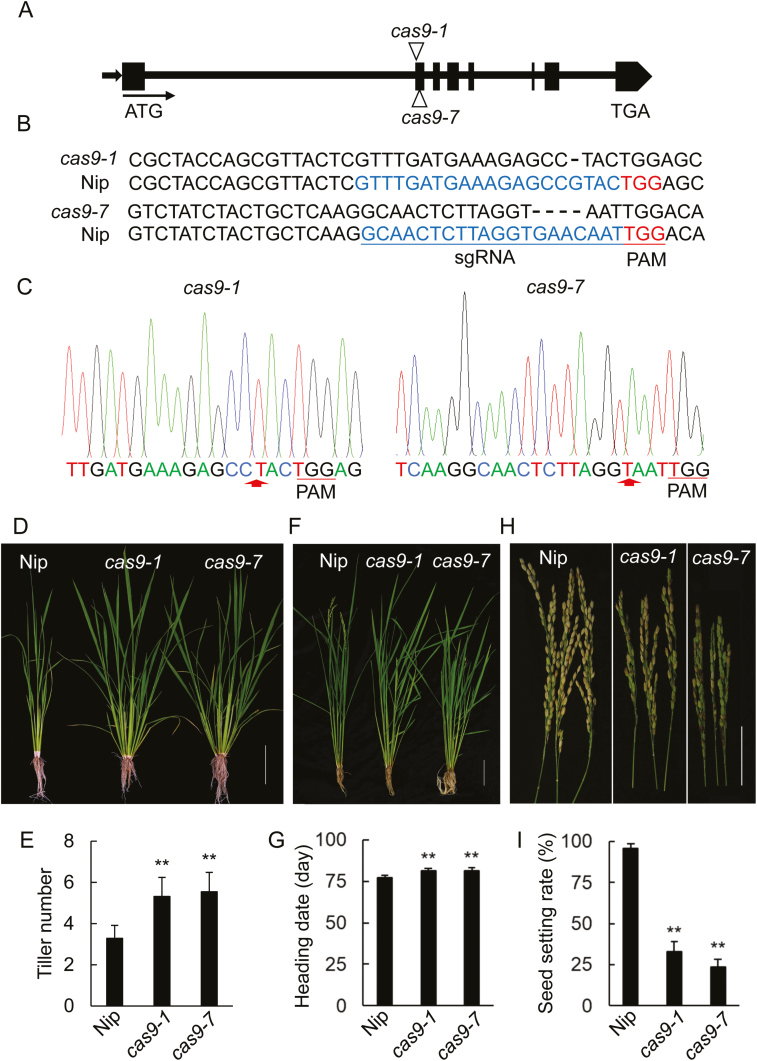

Development is altered in the targeted osmads18 genome-edited mutants

We generated loss-of-function osmads18 mutants using the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system (Feng et al., 2013). Several mutant lines with different types of base-pair deletions in the second exon of OsMADS18 were identified using sequencing, two of which, cas9-1 (one base pair deleted) and cas9-7 (four base pairs deleted), were subjected to further analysis (Fig. 2A–C). The development of the cas9 mutants was significantly different from that of Nip. These knockout mutants produced more tillers than Nip, had a slightly delayed heading date, and showed severely altered panicle architecture and decreased seed setting (Fig. 2D–I). Blocking OsMADS18 function therefore affects the vegetative and reproductive development of rice.

Fig. 2.

Characterization of targeted OsMADS18 genome-edited mutants. (A) Schematic diagram (not to scale) of the CRISPR/Cas9 targeted sites in two mutant alleles, named cas9-1 and cas9-7. Arrows indicate the transcription orientation of OsMADS18. (B) Targeted and edited DNA sequences in OsMADS18. The dashed line indicates the deletion in the DNA sequences. sgRNA, single guide RNA; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif. (C) Sequences of genomic DNA fragments amplified from the cas9-1 and cas9-7 plants . Arrows indicate the deletion sites of the DNA base pairs. (D) 55-day-old cas9-1 and cas9-7 plants had more tillers than Nip plants of the same age. Plants were grown in natural conditions. Scale bar=10 cm. (E) Tiller numbers for Nip and the cas9 lines. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (F) 80-day-old cas9-1 and cas9-7 plants showed a delayed flowering phenotype. Plants were grown in natural conditions. Scale bar=5 cm. (G) Heading date for Nip and the cas9 lines. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (H) The cas9-1 and cas9-7 plants had smaller panicles and fewer seeds. Scale bar=5 cm. (I) Seed setting rate in Nip and the cas9 lines. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

OsMADS18 displays spatiotemporal plasma membrane and nuclear localization characteristics

We investigated the cellular localization of OsMADS18 in both Nip protoplasts and sheath cells derived from transgenic rice plants expressing an EYFP-tagged OsMADS18 protein. We found that EYFP-OsMADS18 was localized either at the plasma membrane or in the nucleus, depending on the developmental stage of the plant (Fig. 3A–D). In protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip seedlings and sheath cells of EYFP-OsMADS18 transgenic seedlings of the same age, the EYFP-OsMADS18 fusion protein was mainly distributed at the plasma membrane. This localization was confirmed by revealing that EYFP-OsMADS18 was co-localized with CFP-OsPRA2, a protein known to be localized to the plasma membrane (Zhang et al., 2016), as well as with Dil, a fluorescent lipophilic cationic indocarbocyanine dye (Fig. 3C, D). In protoplasts isolated from 35-day-old Nip plants and sheath cells of EYFP-OsMADS18 transgenic plants of the same age, the EYFP-OsMADS18 signal was weakly but clearly detected in the nucleus. The nuclear localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 was verified by its co-localization with CFP-DLT, a known nuclear localization protein (Tong et al., 2009), as well as with DAPI (Fig. 3A, D).

Fig. 3.

OsMADS18 has nucleus-localization and plasma membrane-localization traits. (A) Co-localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 and CFP-OsPRA2 at the plasma membrane in protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip seedlings. Scale bar=10 μm. (B) Co-localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 and Dil (a marker for the plasma membrane) at the plasma membrane in sheath cells of 7-day-old seedlings of the EYFP-OsMADS18 transgenic line. Scale bar=10 μm. (C) Co-localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 and CFP-DLT (a marker for the nucleus) in protoplasts isolated from 35-day-old Nip seedlings. Scale bar=10 μm. (D) Co-localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 and DAPI (a marker for the nucleus) in the sheath cells of 35-day-old seedlings of the EYFP-OsMADS18 transgenic line. Scale bar=10 μm. (E) Schematic diagram (not to scale) of the structure of full-length OsMADS18, OsMADS18-N, and OsMADS18-C proteins. (F) Nuclear localization of OsMADS18-N (EYM18-N) in protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip seedlings. Scale bar=10 μm. (G) Detection of OsMADS18-C (EYM18-C) in protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip seedlings. EYFP, Empty vector. Scale bar=10 μm. (H) Intensity of fluorescence (shown as a two-dimensional histogram projection) of EYFP-OsMADS18 (EYM18), EYFP-OsMADS18-N (EYM18-N), and EYFP-OsMADS18-C (EYM18-C) in protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip seedlings. (I) Expression level of OsMADS18-N in 15-day-old seedlings of transgenic lines harboring pCAMBIA1300-EYFP (empty vector EYFP) or pCAMBIA1300-EYFP-OsMADS18-N (N-1, N-3, N-7). OsACTIN1 expression was used as an internal control. The expression level of OsMADS18 was analyzed relative to the level of gene expression in plants carrying the empty vector EYFP, which was assigned a value of 1. (J) Cellular localization of OsMADS18 and OsMADS18-N in the sheath cells of 7-day-old (left panel) and 60-day-old (right panel) transgenic plants. Scale bar=10 μm.

Considering the known functional relationship between OsMADS18, OsMADS14, and OsMADS15 (Kobayashi et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2017), we then compared the cellular localization properties of EYFP-OsMADS18 with those of EYFP-OsMADS14 and EYFP-OsMADS15. The EYFP-OsMADS14 and EYFP-OsMADS15 signals were only ever detected in the nucleus, regardless of the developmental stage of the plants (Supplementary Fig. S3). Hence, the spatiotemporal localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 may distinguish its function from that of other MADS-box proteins, such as OsMADS14 and OsMADS15.

OsMADS18 belongs to the type II lineage of MADS-domain proteins (Smaczniak et al., 2012). It has a modular MIKC structure containing an N-terminal DNA-binding MADS domain [M; 10–65 amino acids (aa)], an intervening region (I; 66–84 aa), a keratin-like region (K; 85–171 aa), and a C-terminal domain (C; 172–249 aa) (Fig. 3E). The I and K regions are crucial for protein dimerization and the formation of higher-order complexes, and the C-terminal domain may also play a role in the formation of protein complexes as well as in transcriptional regulation (Kaufmann et al., 2005). To explore the correlation of these protein domains with the cellular localization of OsMADS18, we assessed the localization traits of various truncations of OsMADS18 (Fig. 3E) in rice protoplasts using transient expression assays (Fig. 3F–H). In protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip seedlings, EYFP-OsMADS18-N (EYM18-N; 1–171 aa) was mainly detected in the nucleus (Fig. 3F), whereas EYFP-OsMADS18-C (EYM18-C; 172–249 aa) was present throughout the cell (Fig. 3G, H). We also examined the cellular localization of EYFP-OsMADS18-N in the sheath cells of 7-day-old and 60-day-old transgenic plants carrying the plasmid pEYFP-OsMADS18-N, in which EYFP-OsMADS18-N was also localized in the nucleus (Fig. 3I, J). The EYFP-tagged N-terminus of OsMADS18 was therefore shown to be necessary and sufficient for nuclear localization.

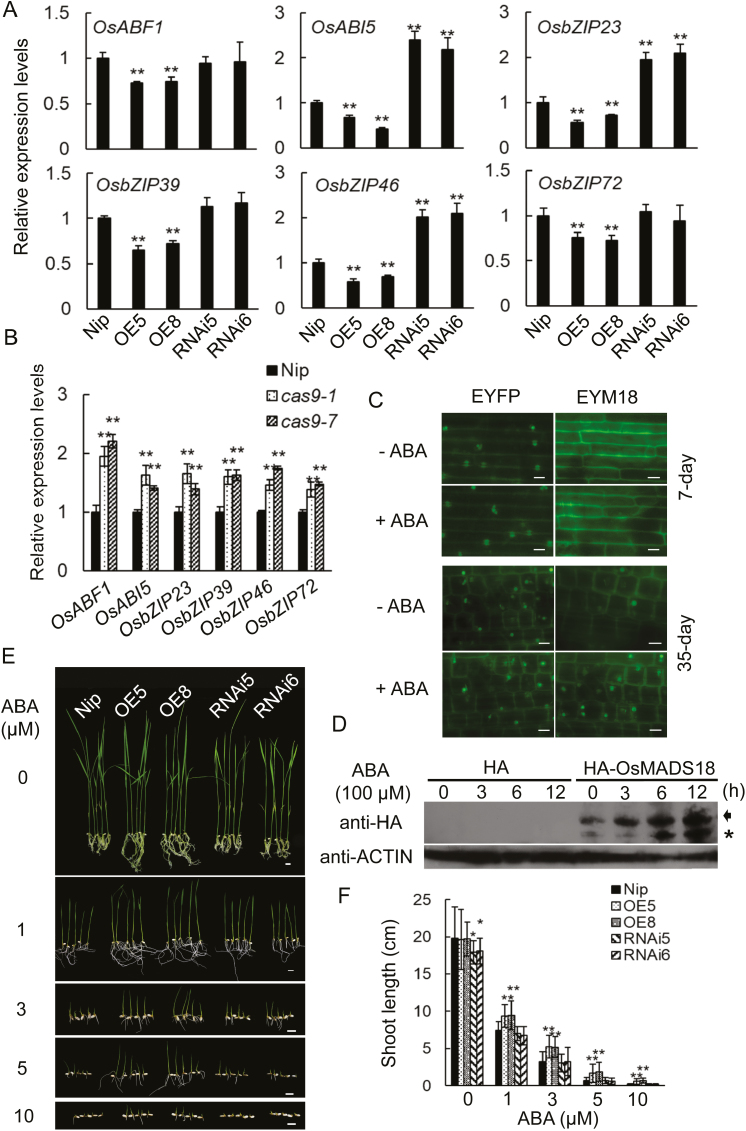

ABA induces OsMADS18 expression

While analyzing the gene sequence properties of OsMADS18, we detected five putative ABA-responsive elements (ABREs; PyACGTGG/TG) in its promoter region (from –1.0 kb to the start codon ATG; Supplementary Fig. S4A). We therefore tested the responsiveness of OsMADS18 to ABA, and found that OsMADS18 expression was indeed stimulated by treatment with 100 μM ABA (Supplementary Fig. S4B). To investigate the relationship between ABA and OsMADS18, we compared the expression levels of a set of ABA-responsive genes in 45-day-old Nip, OE, RNAi, and cas9 plants. Almost all the tested genes were down-regulated in the OE plants but up-regulated in the RNAi and cas9 plants (Fig. 4A, B). The expression levels of a subset of genes, such as OsABF1 (ABRE-BINDING FACTOR 1; Amir Hossain et al., 2010), OsABI5 (ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE 5; Zou et al., 2007), OsbZIP23 (basic leucine zipper 23; Xiang et al., 2008), OsbZIP39 (Takahashi et al., 2012), OsbZIP46/OsABF2/ABL1 (ABI5-Like gene 1; Tang et al., 2012), and OsbZIP72 (Lu et al., 2009) were decreased in the OE plants (Fig. 4A), while the expression levels of OsABI5, OsbZIP23, and OsbZIP46 were increased in the RNAi (Fig. 4A) and cas9 (Fig. 4B) plants.

Fig. 4.

OsMADS18 responds to ABA. (A) Expression levels of a set of ABA-responsive genes in Nip, OE, and RNAi plants. RNAs were extracted from the blades of 45-day-old plants. OsACTIN1 expression was used as an internal control. The expression level was analyzed relative to the level of gene expression in Nip, which was assigned a value of 1. Data represent the mean ±SD of three replicates. **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (B) Expressions level of a set of ABA responsive genes in Nip and cas9 plants. RNAs were extracted from the blades of 45-day-old plants. OsACTIN1 expression was used as an internal control. The expression level was analyzed relative to the level of gene expression in Nip, which was assigned a value of 1. Data represent the mean ±SD of three replicates. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (C) EYFP-OsMADS18 (EYM18) was mostly detected in the plasma membrane of the sheath cells of 7-day-old EYFP-OsMADS18 plants treated with 100 μM ABA for 6 h (upper panel), but in the nuclei of sheath cells of 35-day-old EYFP-OsMADS18 plants treated with 100 μM ABA for 6 h (lower panel). EYFP represents the control transgenic line carrying the empty vector. Scale bar=10 μm. (D) ABA triggers the accumulation and cleavage of OsMADS18 protein in 35-day-old HA-OsMADS18 transgenic plants. The control transgenic line carries the empty vector (HA). Blades from 35-day-old plants were subjected to treatment with 100 μM ABA treatment for the indicated time periods. The arrow indicates the precursor form of HA-OsMADS18 and the asterisk indicates the cleaved form. ACTIN was used as a loading control. Anti-HA antibody was used to detect HA-OsMADS18. (E) Shoot growth in OE lines was less affected by ABA than in Nip and RNAi lines. Seeds were sown on MS plates and after 24 h were transferred to the MS plates containing different concentrations of ABA as indicated. Photographs were taken on day 9 after transfer. Scale bar=0.5 cm. (F) Shoot length quantified at day 9 after transfer. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

To determine whether ABA could influence the localization of EYFP-OsMADS18, we compared its localization in sheath cells from 7-day-old and 35-day-old EYFP-OsMADS18-expressing plants with or without a 6 h treatment with 100 μM ABA. Plasma membrane localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 was observed in the sheath cells of ABA-treated 7-day-old plants, but in ABA-treated 35-day-old plants, EYFP-OsMADS18 was largely localized in the nuclei of sheath cells (Fig. 4C); this observation prompted us to further explore the impact of ABA on the abundance of OsMADS18 protein in rice. The leaf blades of transgenic plants expressing a HA-tagged OsMADS18 protein were subjected to treatment with 100 μM ABA, after which the abundance of HA-OsMADS18 was determined using an immunoblotting approach. This analysis revealed that the ABA treatment not only stimulated the accumulation of HA-OsMADS18 protein, but also promoted its cleavage (Fig. 4D). Generally, MTFs can be cleaved and released from the intracellular membranes in response to a signal (Zhou et al., 2015), after which the cleaved MTFs are translocated to the nucleus to regulate the expression of their target genes (Seo et al., 2008). Our findings suggest that OsMADS18 may act as a MTF in response to ABA.

Since the cellular localization of EYFP-OsMADS18 can be influenced by ABA, we sought to investigate the effect of ABA on the growth of rice plants. We characterized the growth phenotype of Nip, OE, and RNAi seedlings with or without various ABA treatments. Overall, the higher the concentration of ABA that was applied, the stronger its inhibitory effect on the growth of the seedlings, regardless of their genetic background. The inhibitory effect of ABA on the growth of the OE seedlings was relatively weaker than that for the other genotypes (Fig. 4E, F). These data further demonstrate that OsMADS18 is responsive to ABA.

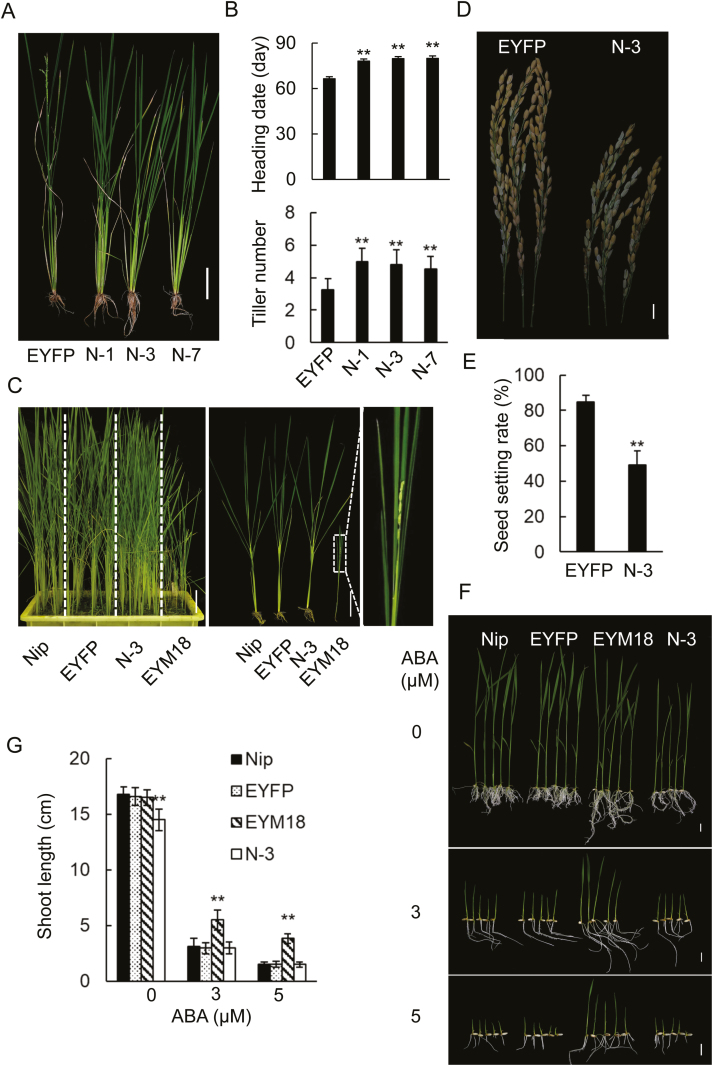

Plants expressing a truncated OsMADS18 lacking a C-terminus have similar phenotypes to the cas9 mutants

A previous study revealed that removing the C-terminal domains of some MADS-box members does not affect their function (Piwarzyk et al., 2007). To determine the importance of the C-terminal domains of OsMADS18, we generated and analyzed transgenic lines expressing EYFP-OsMADS18-N and OsMADS18-C. The OsMADS18-C (C-4) plants showed no significant phenotypic differences from Nip plants (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, the phenotypes of the EYFP-OsMADS18-N (N-1, N-3, and N-7) plants were markedly different from Nip, EYFP (empty vector control), and EYFP-OsMADS18 plants; they produced more tillers and had a delayed heading time and reduced seed setting (Fig. 5A–E). These phenomena were surprisingly similar to the phenotypes of the cas9-1 and cas9-7 mutants (Fig. 2). We also treated EYFP-OsMADS18-N-3 seedlings with ABA; however, this treatment did not significantly alter the growth of these plants (Fig. 5F, G). Taken together, these results indirectly suggested that the C-terminal domain is important for the normal function of OsMADS18 in rice.

Fig. 5.

Altered growth phenotypes in transgenic plants expressing EYFP-OsMADS18-N. (A) Compared to EYFP (empty vector) plants, plants (N-1, N-3, N-7) expressing EYFP-OsMADS18-N had an increased tiller number and delayed flowering time. Plants shown are 67 days old and were grown in a greenhouse. Scale bar=10 cm. (B) Heading date and tiller number in plants (N-1, N-3, N-7) expressing EYFP-OsMADS18-N or empty vector EYFP. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (C) Growth phenotypes of Nip, EYFP, N-3, and EYM18 (EYFP-OsMADS18) plants. All plants were 45 days old and were grown in a greenhouse. The enlarged image shows the early flowering in EYM18. Scale bar=10 cm. (D) N-3 plants had smaller panicles and fewer seeds than EYFP plants. Scale bar=5 cm. (E) Seed setting rate in N-3 and EYFP plants. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>20 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test). (F) The growth of N-3 plants was inhibited by ABA in a manner similar to that of Nip. Seeds were germinated on MS plates for 24 h and then transferred to MS plates with ABA (0, 3, 5 μM). Photographs were taken on day 9 after transfer. Scale bar=1 cm. (G) Shoot length measured on day 9 after transfer. Data represent the mean ±SD of three independent experiments (n>25 for each experiment). **P<0.01 (Student’s t-test).

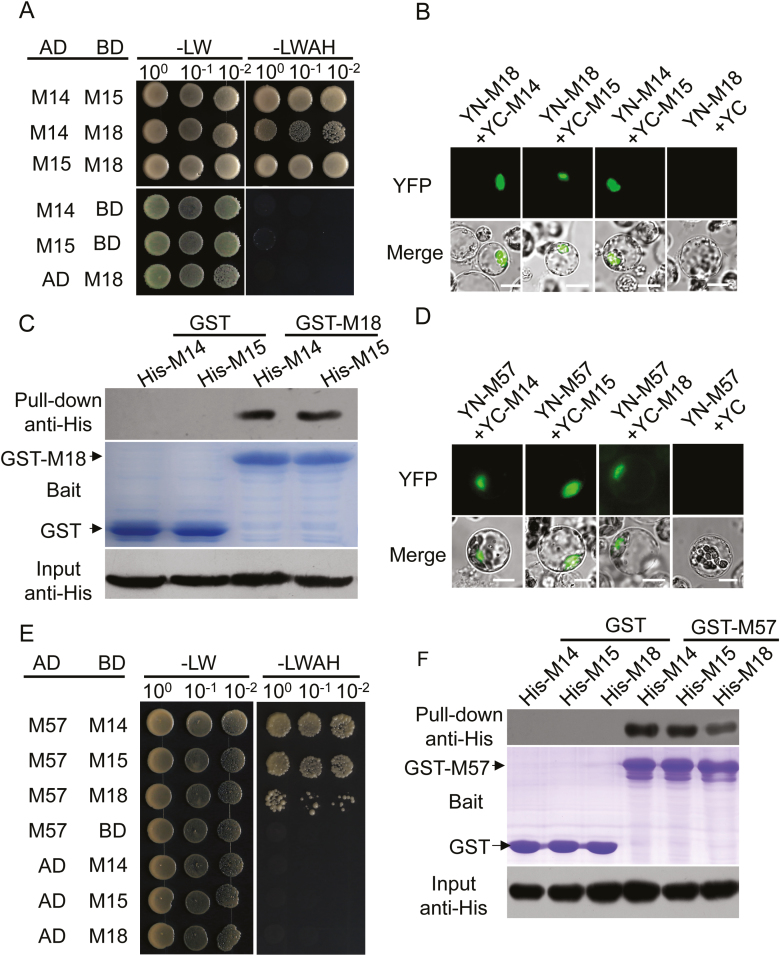

OsMADS18 interacts with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS57

OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 are known to interact with each other (Kobayashi et al., 2012). OsMADS18 has the highest sequence similarity to OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 of any AP1/FUL-like paralog in the rice genome (Yamaguchi and Hirano, 2006); therefore, we sought to explore whether it could interact with these proteins. By annotating their protein sequences, we revealed that OsMADS18 shares 51.97% of its sequence with OsMADS14 and 49.81% with OsMADS15. When their divergent C-terminal domains were not considered, the similarity levels of OsMADS18 to OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 were 63.16% and 65.50%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S6A). By combining methods such as yeast two-hybrid (Y2H), BiFC, and protein pull-down assays, we confirmed that OsMADS18 could directly interact with OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 (Fig. 6A–C). The interactions between OsMADS18 and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 were detected in the nuclei of protoplasts isolated from 35-day-old rice plants (Fig. 6B) as well as from 5-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings transiently expressing the rice genes (Supplementary Fig. S6B). However, no interaction between OsMADS18 and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 was detected in protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old rice plants (Supplementary Fig. S6C). To determine which domain is essential for these interactions, we evaluated the interactions of the truncated OsMADS18 proteins with OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 in a Y2H assay. Only the N-terminal domain of OsMADS18 (OsMADS18-N), and not the C-terminal domain (OsMADS18-C), was able to interact with OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 (Supplementary Fig. S6D). We further characterized these interactions in protoplasts using a transient expression assay, which demonstrated that the interaction between OsMADS18-N and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 took place in the nuclei of protoplasts isolated from 7-day-old Nip plants (Supplementary Fig. S6E), despite no interaction being detected between full-length OsMADS18 and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 in protoplasts at the same developmental stage (Supplementary Fig. S6C).

Fig. 6.

OsMADS18 interacts with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS57. (A) The interaction between OsMADS18 (M18) and OsMADS14 (M14) or OsMADS15 (M15) was analyzed in a Y2H assay. Controls: AD (pGADT7) and BD (pGBKT7); -LW, low-stringency medium (SD/Leu-/Trp-); -LWAH, high-stringency selective medium (SD/Leu-/Trp-/Ade-/His-). (B) The interaction between OsMADS18 (YN-M18) and OsMADS14 (YC-M14) or OsMADS15 (YC-M15) was detected in the nucleus of protoplasts isolated from 35-day-old Nip seedlings in a BiFC assay. YC, C-terminal EYFP fragment, YN, N-terminal EYFP fragment. Scale bar=10 μm. (C) The interaction between OsMADS18 and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 was confirmed in a pull-down assay. The separated GST-OsMADS18 (GST-M18) and GST proteins (bait) in 12% SDS-PAGE gel were visualized with Coomassie staining. The empty vector GST was used as the control. His-OsMADS14 (His-M14) and His-OsMADS15 (His-M15) were immunoblotted with anti-His antibody (Input). (D) The interaction between OsMADS57 (YN-M57) and OsMADS14 (YC-M14), OsMADS15 (YC-M15), or OsMADS18 (YC-M18) was detected in the nucleus of protoplasts isolated from 35-day-old Nip seedlings in a BiFC assay. Scale bar=10 μm. (E) The interaction between OsMADS57 (M57) and OsMADS14 (M14), OsMADS15 (M15), or OsMADS18 (M18) was also analyzed in a Y2H assay. Controls: AD (pGADT7) and BD (pGBKT7); -LW, low-stringency medium (SD/Leu-/Trp-); -LWAH, high-stringency selective medium (SD/Leu-/Trp-/Ade-/His-). (F) The interaction of OsMADS57 with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, or OsMADS18 was confirmed in a pull-down assay. The separated GST-OsMADS57 (GST-M57) and GST proteins (bait) in 12% SDS-PAGE gel were visualized with Coomassie staining. The empty vector GST was used as the control. His-OsMADS14 (His-M14), His-OsMADS15 (His-M15), and His-OsMADS18 (His-M18) were immunoblotted with anti-His antibody (Input).

OsMADS57 plays a crucial role in SL-mediated tiller development in rice (Guo et al., 2013). Since tillering was severely affected in the OE plants in the present study (Fig. 1C), we investigated whether there was any connection between OsMADS18 and OsMADS57. Similar to the interactions between OsMADS18 and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15, an interaction between OsMADS18 with OsMADS57 was detected in the nuclei of protoplasts isolated from 35-day-old, but not 7-day-old, Nip plants (Fig. 6D; Supplementary Fig. S6F). This interaction was confirmed using Y2H and protein pull-down assays (Fig. 6E, F). Additionally, we revealed that OsMADS57 could interact with OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in the nucleus, regardless of the developmental stage of the Nip plants (Fig. 6D–F; Supplementary Fig. S6F).

Next, we investigated the genetic significance of the interaction between OsMADS18 and OsMADS14 or OsMADS15. We generated transgenic lines overexpressing OsMADS14 (M14) or OsMADS15 (M15) (Supplementary Fig. S7A), neither of which showed any difference in growth compared with Nip before 30 days, while the line OE8 already showed the reduced tiller phenotype (Supplementary Fig. S7B). At the mature flowering stage, however, M14 and M15 produced significantly fewer tillers than Nip (Supplementary Fig. S7C, D). This phenotype was reminiscent of the reduced number of tillers produced by OE8 (Fig. 1C, D; Supplementary Fig. S7B), and is also similar to the phenotype reported for RNAi lines of OsMADS57 (Guo et al., 2013).

Discussion

OsMADS18 affects seed germination and plant architecture

The MADS-box proteins are involved in diverse developmental processes in rice (Smaczniak et al., 2012; Callens et al., 2018). OsMADS18, one of the AP1/FUL-like subfamily of MADS-box proteins, has been reported to play significant roles in rice development (Fornara et al., 2004), and is known to have overlapping functions with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and PAP2 in specifying inflorescence initiation (Kobayashi et al., 2012). During seed maturation, the down-regulation of OsMADS18 expression results in some green endosperm grains and reduces the seed setting rate, while the simultaneous loss of OsMADS18 and either OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 causes the seeds to be shrunken (Wu et al., 2017). These previous discoveries highlight that OsMADS18 is indispensable for rice development.

Although OsMADS18 has a pronounced role in the flowering and formation of floral organs in rice (Fornara et al., 2004; Kobayashi et al., 2012), its function in other developmental processes, such as seed germination and tiller formation, is elusive. The delayed seed germination and retarded early seedling growth of the OsMADS18 RNAi lines (Fig. 1A, B) was most likely associated with the increased chalkiness of their seeds (Supplementary Fig. S2C, D). In general, chalky seeds often result in delayed seed germination and impaired seedling growth (Zhang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015). The down-regulation or loss of function of several genes has been reported to cause seed chalkiness, including OsMADS6 (Zhang et al., 2010), OsNF-YB1 (Nuclear Factor Y B1; Sun et al., 2014; Bai et al., 2016), and OsMADS29 (Yang et al., 2012). Considering the potential interaction of OsMADS6, OsMADS29, or OsNF-YB1 with OsMADS18 (Moon et al., 1999; Masiero et al., 2002; Nayar et al., 2014), we speculate that OsMADS18 may function together with OsMADS6, OsMADS29, or OsNF-YB1 to control grain quality.

Previous reports have demonstrated that early flowering can be induced in plants overexpressing OsMADS18; however, no growth defects were observed in the OsMADS18 RNAi knockdown lines (Fornara et al., 2004; Kobayashi et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2017). The effect of complete loss of OsMADS18 function has not previously been reported, however. In this study, we generated knockout osmads18 mutants (cas9-1 and cas9-7) using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing (Fig. 2A–C), and characterized their growth phenotypes. These cas9 mutants produced more tillers and had slightly delayed flowering times (Fig. 2D–I), demonstrating the importance of OsMADS18 in tiller formation and the floral transition of rice.

When the C-terminal domain of OsMADS18 was removed, the OsMADS18-N protein caused phenotypes similar to those of the cas9 mutants, in contrast to those produced in the OsMADS18 OE lines (Fig. 5A–E). Given the fact that both full-length OsMADS18 and OsMADS18-N could interact with OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in the nucleus (Fig. 6A–C; Supplementary Fig. S6B), we hypothesize that the N-terminal domain of OsMADS18 is crucial for its interaction with its partner proteins in the nucleus, leading to a dominant negative effect. Mature plants (55 days old) overexpressing OsMADS14 (M14) or OsMADS15 (M15) had reduced tiller numbers (Supplementary Fig. S7), demonstrating that the functional effects of OsMADS14 or OsMADS15 were related to those of OsMADS18. Generally, the expression of OsMADS18 can be detected in plants over 4 weeks old (Supplementary Fig. S1), which suggests that OsMADS18 might be involved in the growth of M14 or M15 plants at later developmental stages. In addition, OsMADS18 also interacts with OsMADS57 (Fig. 6D–F). By binding to the promoter of the SL receptor gene D14, OsMADS57 is believed to play a key role in SL-mediated vegetative growth in rice. The overexpression of OsMADS57 can significantly increase the number of tillers produced, whereas its down-regulation can inhibit auxiliary branch growth (Guo et al., 2013). These results suggest that OsMADS18 may coordinate its function with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and/or OsMADS57 to regulate tiller formation in rice.

Auxin regulates plant growth and development by controlling cell division, elongation, and differentiation. The crosstalk between the auxin- and SL-signaling pathways is important for the outgrowth and secondary growth of buds (Brewer et al., 2009; Agusti et al., 2011; Kapulnik et al., 2011). Here, we showed that plants overexpressing OsMADS18 have decreased IAA contents (Fig. 1G) and altered expression levels of D14 and OsTB1 (Fig. 1F), two key components in SL signaling (Minakuchi et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2016). These findings suggest that OsMADS18 is involved in both auxin- and SL-regulated growth in rice. Future studies should address these relationships to further elucidate the mechanisms by which OsMADS18 modulates rice development.

OsMADS18 responds to ABA signaling

The MADS-box transcription factors are classified by their common DNA-binding domain, which enables them to recognize similar DNA sequences (Smaczniak et al., 2012). Some transcription factors, known as MTFs, are translated but remain dormant in the cytoplasmic pool and/or are anchored to intracellular membrane systems, usually at their C-terminus, but can be activated by environmental signals (Vik and Rine, 2000; Seo et al., 2008). It is believed that MTFs play important roles in the adaption to environmental stresses and endoplasmic reticulum stress (Slabaugh and Brandizzi, 2011; Liu et al., 2018). Once stimulated, the MTFs are usually cleaved from the membranes by a ubiquitin–proteasome mechanism or membrane-associated proteases, freeing them to be translocated to the nucleus to execute their regulatory roles on the transcription of genes responding to the stress (Seo et al., 2008). A genome-wide analysis indicated that over 10% of all transcription factors in plants are membrane-bound; however, very few studies have been performed on plant MTFs, except for the NAC (NAM, ATAF, and CUC) family and some bZIP members (Seo et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2018).

We showed that the full-length OsMADS18 protein was detectable near the cell periphery and the plasma membrane of the sheath cells and protoplasts of 7-day-old Nip seedlings, while in 60-day-old sheath cells it was present in the nucleus, cytosol, and at the plasma membrane (Fig. 3J). When the C-terminal domain of OsMADS18 was removed, the resulting EYFP-OsMADS18-N protein was mainly detected in the nucleus (Fig. 3F, H), suggesting that the C-terminus of OsMADS18 is vital for membrane anchoring. The removal of the N-terminal domain caused the resulting EYFP-OsMADS18-C protein to be distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 3G, H). The spatiotemporal nuclear and plasma membrane localization traits of OsMADS18 suggest that it functions in specific stages during rice development; OsMADS18 was largely localized at the plasma membranes of cells in younger (7-day-old) seedlings (Fig. 3A, B), but was predominantly present in the nuclei of cells in older plants (Fig. 3J).

The plasma-membrane-bound trait of OsMADS18 suggests that it may respond to specific signals. By analyzing the genomic DNA sequence of OsMADS18, we identified five putative ABREs in its promoter region (Supplementary Fig. S4A), suggesting a connection between OsMADS18 function and ABA signaling. Indeed, OsMADS18 expression could be induced by exogenous ABA treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4B), while altering the expression level of OsMADS18 also altered the transcription of a set of ABA-related genes (Fig. 4A, B). The ABA treatment triggered the accumulation of EYFP-OsMADS18 in the nucleus (Fig. 4C), while the inhibitory effect of ABA on shoot growth was reduced in the OE plants (Fig. 4E, F); these findings both demonstrated the influence of ABA on the function of OsMADS18 in rice. In Arabidopsis, FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), a MADS-box member, was found to function downstream of ABI5 during ABA-mediated inhibition of the floral transition (Wang et al., 2013). The FLC-like cluster may also function as a facilitator for rapid adaptations to changes in the ambient temperature (Theißen et al., 2018). Since rice does not require vernalization before flowering, the FLC clade is believed to have been lost from the rice genome over the course of its evolution (Arora et al., 2007). The way in which the MADS-box members substitute for the roles of FLC in ABA-mediated inhibition of the rice floral transition has yet to be elucidated, and future studies investigating whether OsMADS18 plays a similar role to Arabidopsis FLC are likely to yield intriguing results.

Overall, our study highlights that OsMADS18 can function as a MTF and play a pleiotropic role in rice development, including seed maturation and germination, tiller formation, and the response to ABA. Future studies should investigate the regulatory mechanisms concerning the interaction of OsMADS18 and OsMADS57 in SL-mediated tiller formation and the role of OsMADS18 in ABA signaling, which will expand our understanding of the roles of OsMADS18 in rice development.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Analysis of the expression patterns of OsMADS18 in various tissues of rice.

Fig. S2. Comparison of chalkiness in seeds of Nip, OE, and RNAi lines.

Fig. S3. Characterization of the cellular localization of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in Nip protoplasts.

Fig. S4. ABA triggers expression of OsMADS18 in rice.

Fig. S5. OsMADS18-C plants show no significant difference from Nip plants.

Fig. S6. Analysis of the interaction of OsMADS18 with OsMADS14, OsMADS15, and OsMADS57.

Fig. S7. Altered plant growth in transgenic plants overexpressing OsMADS14, OsMADS15, or OsMADS18.

Table S1. Primer sequences used for plasmid construction in this study.

Table S2. Primer sequences used for qRT–PCR analyses.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Wu Lab for their technical help and comments on this manuscript. We thank Dr Jie Zhao (College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, China) for kindly providing seeds of Nip. We thank the Large-scale Instrument and Equipment Sharing Foundation of Wuhan University for supporting the use of the instruments in the College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University. This work was supported by grants to Y.W. from the Major State Basic Research Program from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2013CB126900), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31270333).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ABA

abscisic acid

- ABRE

abscisic acid-responsive element

- BiFC

bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- CDS

coding sequence

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- MTF

membrane-bound transcription factor

- OE

overexpression

- RNAi

RNA interference

- SL

strigolactone

- Y2H

yeast two-hybrid.

References

- Agusti J, Herold S, Schwarz M, et al. 2011. Strigolactone signaling is required for auxin-dependent stimulation of secondary growth in plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 20242–20247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir Hossain M, Lee Y, Cho JI, Ahn CH, Lee SK, Jeon JS, Kang H, Lee CH, An G, Park PB. 2010. The bZIP transcription factor OsABF1 is an ABA responsive element binding factor that enhances abiotic stress signaling in rice. Plant Molecular Biology 72, 557–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arite T, Umehara M, Ishikawa S, Hanada A, Maekawa M, Yamaguchi S, Kyozuka J. 2009. d14, a strigolactone-insensitive mutant of rice, shows an accelerated outgrowth of tillers. Plant & Cell Physiology 50, 1416–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora R, Agarwal P, Ray S, Singh AK, Singh VP, Tyagi AK, Kapoor S. 2007. MADS-box gene family in rice: genome-wide identification, organization and expression profiling during reproductive development and stress. BMC Genomics 8, 242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai AN, Lu XD, Li DQ, Liu JX, Liu CM. 2016. NF-YB1-regulated expression of sucrose transporters in aleurone facilitates sugar loading to rice endosperm. Cell Research 26, 384–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer PB, Dun EA, Ferguson BJ, Rameau C, Beveridge CA. 2009. Strigolactone acts downstream of auxin to regulate bud outgrowth in pea and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 150, 482–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callens C, Tucker MR, Zhang D, Wilson ZA. 2018. Dissecting the role of MADS-box genes in monocot floral development and diversity. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 2435–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YN, Slabaugh E, Brandizzi F. 2008. Membrane-tethered transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana: novel regulators in stress response and development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 11, 695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Li L, Xu B, Zhao S, Lu P, He Y, Ye T, Feng Y, Wu Y. 2019. Phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C2 functions in auxin-modulated root development. Plant, Cell and Environment 42, 1441–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AH, Quail PH. 1996. Ubiquitin promoter-based vectors for high-level expression of selectable and/or screenable marker genes in monocotyledonous plants. Transgenic Research 5, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Zhang B, Ding W, et al. 2013. Efficient genome editing in plants using a CRISPR/Cas system. Cell Research 23, 1229–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornara F, Parenicová L, Falasca G, Pelucchi N, Masiero S, Ciannamea S, Lopez-Dee Z, Altamura MM, Colombo L, Kater MM. 2004. Functional characterization of OsMADS18, a member of the AP1/SQUA subfamily of MADS box genes. Plant Physiology 135, 2207–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Xu Y, Liu H, Mao Z, Zhang C, Ma Y, Zhang Q, Meng Z, Chong K. 2013. The interaction between OsMADS57 and OsTB1 modulates rice tillering via DWARF14. Nature Communications 4, 1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA, Kavanagh TA, Bevan MW. 1987. GUS fusions: beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. The EMBO Journal 6, 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JS, Lee S, Jung KH, Yang WS, Yi GH, Oh BG, An GH. 2000. Production of transgenic rice plants showing reduced heading date and plant height by ectopic expression of rice MADS-box genes. Molecular Breeding 6, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Wang Y, Xue D, et al. 2010. Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nature Genetics 42, 541–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapulnik Y, Resnick N, Mayzlish-Gati E, Kaplan Y, Wininger S, Hershenhorn J, Koltai H. 2011. Strigolactones interact with ethylene and auxin in regulating root-hair elongation in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2915–2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann K, Melzer R, Theissen G. 2005. MIKC-type MADS-domain proteins: structural modularity, protein interactions and network evolution in land plants. Gene 347, 183–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush GS. 1995. Breaking the yield frontier of rice. GeoJournal 35, 329–332. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Yasuno N, Sato Y, Yoda M, Yamazaki R, Kimizu M, Yoshida H, Nagamura Y, Kyozuka J. 2012. Inflorescence meristem identity in rice is specified by overlapping functions of three AP1/FUL-like MADS box genes and PAP2, a SEPALLATA MADS box gene. The Plant Cell 24, 1848–1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, He Y, Wang Y, Zhao S, Chen X, Ye T, Wu Y, Wu Y. 2015. Arabidopsis PLC2 is involved in auxin-modulated reproductive development. The Plant Journal 84, 504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Qian Q, Fu Z, et al. 2003. Control of tillering in rice. Nature 422, 618–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt A, Irish VF. 2003. Duplication and diversification in the APETALA1/FRUITFULL floral homeotic gene lineage: implications for the evolution of floral development. Genetics 165, 821–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Li P, Fan L, Wu M. 2018. The nuclear transportation routes of membrane-bound transcription factors. Cell Communication and Signaling 16, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Coneva V, Casaretto JA, Ying S, Mahmood K, Liu F, Nambara E, Bi YM, Rothstein SJ. 2015. OsPIN5b modulates rice (Oryza sativa) plant architecture and yield by changing auxin homeostasis, transport and distribution. The Plant Journal 83, 913–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Gao C, Zheng X, Han B. 2009. Identification of OsbZIP72 as a positive regulator of ABA response and drought tolerance in rice. Planta 229, 605–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Wei H, Wang Y, Wang H, Yang R, Zhang X, Tu J. 2012. Over-expression of a transcription factor OsMADS15 modifies plant architecture and flowering time in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Molecular Biology Reporter 30, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Chen X, Wu Y, Wang Y, He Y, Wu Y. 2013. Directly transforming PCR-amplified DNA fragments into plant cells is a versatile system that facilitates the transient expression assay. PLoS One 8, e57171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiero S, Imbriano C, Ravasio F, Favaro R, Pelucchi N, Gorla MS, Mantovani R, Colombo L, Kater MM. 2002. Ternary complex formation between MADS-box transcription factors and the histone fold protein NF-YB. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 277, 26429–26435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakuchi K, Kameoka H, Yasuno N, et al. 2010. FINE CULM1 (FC1) works downstream of strigolactones to inhibit the outgrowth of axillary buds in rice. Plant & Cell Physiology 51, 1127–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon YH, Kang HG, Jung JY, Jeon JS, Sung SK, An G. 1999. Determination of the motif responsible for interaction between the rice APETALA1/AGAMOUS-LIKE9 family proteins using a yeast two-hybrid system. Plant Physiology 120, 1193–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar]

- Nayar S, Kapoor M, Kapoor S. 2014. Post-translational regulation of rice MADS29 function: homodimerization or binary interactions with other seed-expressed MADS proteins modulate its translocation into the nucleus. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 5339–5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura A, Aichi I, Matsuoka M. 2006. A protocol for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in rice. Nature Protocols 1, 2796–2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwarzyk E, Yang Y, Jack T. 2007. Conserved C-terminal motifs of the Arabidopsis proteins APETALA3 and PISTILLATA are dispensable for floral organ identity function. Plant Physiology 145, 1495–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian J, Wu C, Chen X, et al. 2014. Differential requirements of arrestin-3 and clathrin for ligand-dependent and -independent internalization of human G protein-coupled receptor 40. Cellular Signalling 26, 2412–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo PJ, Kim SG, Park CM. 2008. Membrane-bound transcription factors in plants. Trends in Plant Science 13, 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Yao X, Ye T, Ma S, Liu X, Yin X, Wu Y. 2018. Arabidopsis aspartic protease ASPG1 affects seed dormancy, seed longevity and seed germination. Plant & Cell Physiology 59, 1415–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AP, Savaldi-Goldstein S. 2015. Growth control: brassinosteroid activity gets context. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slabaugh E, Brandizzi F. 2011. Membrane-tethered transcription factors provide a connection between stress response and developmental pathways. Plant Signaling & Behavior 6, 1210–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaczniak C, Immink RGH, Angenent GC, Kaufmann K. 2012. Developmental and evolutionary diversity of plant MADS-domain factors: insights from recent studies. Development 139, 3081–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Lu Z, Yu H, et al. 2017. IPA1 functions as a downstream transcription factor repressed by D53 in strigolactone signaling in rice. Cell Research 27, 1128–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Ling S, Lu Z, Ouyang YD, Liu S, Yao J. 2014. OsNF-YB1, a rice endosperm-specific gene, is essential for cell proliferation in endosperm development. Gene 551, 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling S, Pan S, Kennedy A, Melzer R. 2018. MADS-box genes and crop domestication: the jack of all traits. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 1447–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kawakatsu T, Wakasa Y, Hayashi S, Takaiwa F. 2012. A rice transmembrane bZIP transcription factor, OsbZIP39, regulates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Plant & Cell Physiology 53, 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T, Suwa Y, Suzuki M, Kitano H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M, Ueguchi C. 2003. The OsTB1 gene negatively regulates lateral branching in rice. The Plant Journal 33, 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N, Zhang H, Li X, Xiao J, Xiong L. 2012. Constitutive activation of transcription factor OsbZIP46 improves drought tolerance in rice. Plant Physiology 158, 1755–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theißen G, Rümpler F, Gramzow L. 2018. Array of MADS-box genes: facilitator for rapid adaptation? Trends in Plant Science 23, 563–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H, Jin Y, Liu W, Li F, Fang J, Yin Y, Qian Q, Zhu L, Chu C. 2009. DWARF AND LOW-TILLERING, a new member of the GRAS family, plays positive roles in brassinosteroid signaling in rice. The Plant Journal 58, 803–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K, Kurata N, Ohyanagi H, Hake S. 2014. Genome-wide study of KNOX regulatory network reveals brassinosteroid catabolic genes important for shoot meristem function in rice. The Plant Cell 26, 3488–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik A, Rine J. 2000. Membrane biology: membrane-regulated transcription. Current Biology 10, R869–R871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Smith SM, Li J. 2018. Genetic regulation of shoot architecture. Annual Review of Plant Biology 69, 437–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhou W, Lu Z, Ouyang Y, Chol Su O, Yao J. 2015. A lipid transfer protein, OsLTPL36, is essential for seed development and seed quality in rice. Plant Science 239, 200–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li L, Ye T, Lu Y, Chen X, Wu Y. 2013. The inhibitory effect of ABA on floral transition is mediated by ABI5 in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li L, Ye T, Zhao S, Liu Z, Feng Y, Wu Y. 2011. Cytokinin antagonizes ABA suppression to seed germination of Arabidopsis by downregulating ABI5 expression. The Plant Journal 68, 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Shi X, Lin X, Liu Y, Chong K, Theißen G, Meng Z. 2017. The ABCs of flower development: mutational analysis of AP1/FUL-like genes in rice provides evidence for a homeotic (A)-function in grasses. The Plant Journal 89, 310–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhao S, Tian H, He Y, Xiong W, Guo L, Wu Y. 2013. CPK3-phosphorylated RhoGDI1 is essential in the development of Arabidopsis seedlings and leaf epidermal cells. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 3327–3338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Tang N, Du H, Ye H, Xiong L. 2008. Characterization of OsbZIP23 as a key player of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family for conferring abscisic acid sensitivity and salinity and drought tolerance in rice. Plant Physiology 148, 1938–1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Ye T, Yao X, Liu X, Ma S, Chen X, Chen ML, Feng YQ, Wu Y. 2018. The dioxygenase GIM2 functions in seed germination by altering gibberellin production in Arabidopsis. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 60, 276–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Wang Y, Yu Y, Duan J, Liao Z, Xiong G, Meng X, Liu G, Qian Q, Li J. 2012. Degradation of MONOCULM 1 by APC/CTAD1 regulates rice tillering. Nature Communications 3, 750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Hirano HY. 2006. Function and diversification of MADS-box genes in rice. The Scientific World Journal 6, 1923–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wu F, Lin X, Du X, Chong K, Gramzow L, Schilling S, Becker A, Theißen G, Meng Z. 2012. Live and let die - the B(sister) MADS-box gene OsMADS29 controls the degeneration of cells in maternal tissues during seed development of rice (Oryza sativa). PLoS One 7, e51435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R, Ming Z, Yan L, et al. 2016. DWARF14 is a non-canonical hormone receptor for strigolactone. Nature 536, 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao R, Wang L, Li Y, Chen L, Li S, Du X, Wang B, Yan J, Li J, Xie D. 2018. Rice DWARF14 acts as an unconventional hormone receptor for strigolactone. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 2355–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Song X, Guo H, Wu Y, Chen X, Fang R. 2016. A small G protein as a novel component of the rice brassinosteroid signal transduction. Molecular Plant 9, 1260–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Nallamilli BR, Mujahid H, Peng Z. 2010. OsMADS6 plays an essential role in endosperm nutrient accumulation and is subject to epigenetic regulation in rice (Oryza sativa). The Plant Journal 64, 604–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XQ, Hou P, Zhu HT, Li GD, Liu XG, Xie XM. 2013. Knockout of the VPS22 component of the ESCRT-II complex in rice (Oryza sativa L.) causes chalky endosperm and early seedling lethality. Molecular Biology Reports 40, 3475–3481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Su J, Duan S, et al. 2011. A highly efficient rice green tissue protoplast system for transient gene expression and studying light/chloroplast-related processes. Plant Methods 7, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Wu Y, He Y, Wang Y, Xiao J, Li L, Wang Y, Chen X, Xiong W, Wu Y. 2015. RopGEF2 is involved in ABA-suppression of seed germination and post-germination growth of Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 84, 886–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SF, Sun L, Valdés AE, Engström P, Song ZT, Lu SJ, Liu JX. 2015. Membrane-associated transcription factor peptidase, site-2 protease, antagonizes ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist 208, 188–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou M, Guan Y, Ren H, Zhang F, Chen F. 2007. Characterization of alternative splicing products of bZIP transcription factors OsABI5. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 360, 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zupicich J, Brenner SE, Skarnes WC. 2001. Computational prediction of membrane-tethered transcription factors. Genome Biology 2, research0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.