Abstract

The highly conserved SNARE protein SEC22B mediates diverse and critical functions, including phagocytosis, cell growth, autophagy, and protein secretion. However, these characterizations have thus far been limited to in vitro work. Here, we expand our understanding of the role Sec22b plays in vivo. We utilized Cre-Lox mice to delete Sec22b in three tissue compartments. With a germline deletion of Sec22b, we observed embryonic death at E8.5. Hematopoietic/endothelial cell deletion of Sec22b also resulted in in utero death. Notably, mice with Sec22b deletion in CD11c-expressing cells of the hematopoietic system survive to adulthood. These data demonstrate Sec22b contributes to early embryogenesis through activity both in hematopoietic/endothelial tissues as well as in other tissues yet to be defined.

Subject terms: Embryology, Development

Introduction

Intracellular trafficking plays a critical role in cellular biology, regulating the distribution and organization of secretory proteins. One protein class which helps mediate this complex choreography is the SNAREs (soluble NSF attachment protein receptor). Partner SNAREs bind and mediate the fusion of two membranes by physically bringing the membranes sufficiently close to fuse1. SEC22B is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-SNARE which localizes to the ER and the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment2. It functions as a vesicular-SNARE3,4 and an R-SNARE engaged in antero- and retrograde ER-Golgi transport5,6. Its known interacting partners are varied. It forms a classic four-helix SNARE complex with Qa-SNARE syntaxin 18, Qb-SNARE BNIP1, and Qc-SNARE p31/Use1 at the ER membrane7. SEC22B is also known to interact with plasma membrane/Qa-SNAREs syntaxin 18, syntaxin 42 and syntaxin 54, suggesting it also functions at the interface between the plasma membrane and the ER membrane.

At the cellular level, in addition to its role in ER-Golgi trafficking, SEC22B appears to mediate membrane expansion under several conditions, including Legionella and Leishmania infection in macrophages9–11 as well as during axonal growth from isolated cortical neurons8. Some evidence suggests that SEC22B contributes to cellular homeostasis as well. For example, in murine macrophages, SEC22B negatively regulates phagocytosis12 but promotes reactive oxygen species accumulation during S. aureus infection13. In flies, Sec22 influences ER morphology14, while in yeast, Sec22 contributes to autophagosome biogenesis15. In human cell lines, SEC22B has been implicated in the secretory autophagy pathway16 as well as in macroautophagy17. SEC22B also contributes to other secretory pathways, such as that in VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein)-secreting rat hepatocytes. Thus, current evidence suggests that Sec22b is highly conserved and plays a fundamental role in cell biology. However, while cDNA library-based expression profiling has demonstrated that Sec22b is expressed in murine embryos18–20, its function in embryogenesis in vivo remains unexplored.

Utilizing Cre-Lox mice, we deleted Sec22b from all tissues, from hematopoietic and endothelial cells, and from CD11c-expressing cells, a subset of the hematopoietic cell population. We observed that Sec22b is critical for embryonic development. Embryos with a global deficiency in Sec22b do not survive beyond 8.5 days post coitum (E8.5). Furthermore, deletion of Sec22b from the hematopoietic compartment with Vav1-Cre results in embryonic lethality. However, normal development was observed with deletion of Sec22b in CD11c-expressing hematopoietic cells.

Results

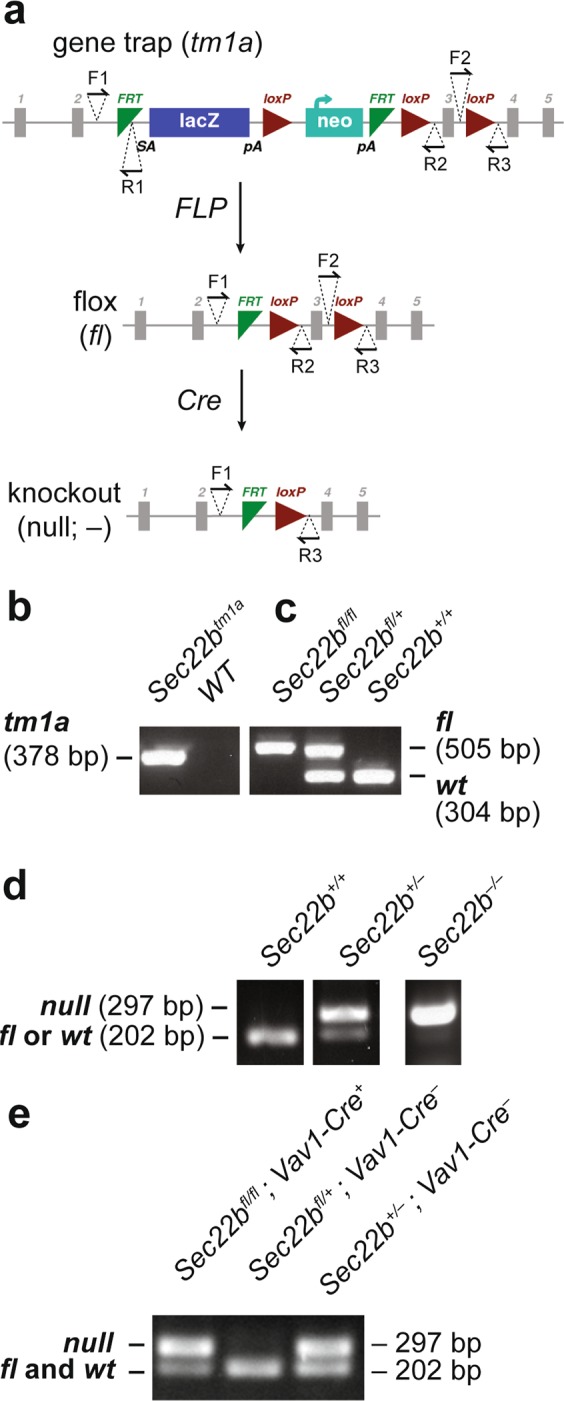

Sec22b is necessary for embryonic development

To determine the role of SEC22B in vivo, we intercrossed mice heterozygous for a FRT recombination site-flanked conditional gene-trapped Sec22b allele (Sec22btm1a/+) (Fig. 1a,b), but did not detect any Sec22btm1a/tm1a offspring at weaning (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). To exclude the possibility that an off target gene trap effect21, as opposed to the loss of functional Sec22b, was responsible for this phenotype, we generated mice heterozygous for the Sec22b null allele (Sec22b+/−). First, we crossed the Sec22btm1a allele to mice expressing FLP recombinase driven by the human β-actin promoter, and excised the gene trap cassette, resulting in the Sec22bfl allele (Fig. 1a,c), where exon 3 is flanked by LoxP sites (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, the Sec22bfl allele was crossed to mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the germline-expressed EIIa promoter, producing the Sec22b− allele (Fig. 1a,d). Sec22b+/− mice exhibited normal survival (p = 0.6473) (Table 1). However, no Sec22b−/− pups were observed at weaning (p = 0.0008) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Generation of gene targeted Sec22b alleles. (a) Sec22b-conditional gene trapped mice (tm1a), with a FRT-flanked gene trap inserted between exons 2 and 3 were mated to FLP-recombinase transgenic mice to create floxed (fl) mice, with LoxP sites flanking exon 3. Floxed mice were mated to EIIa-Cre to generate the germline null allele (Sec22b−), or to Vav1-Cre or CD11c-Cre transgenic mice to generate tissue specific Sec22b deficiency. Binding sites for genotyping primers (F1, F2, R1, R2, R3) are indicated with half arrowheads. (b) PCR with primers F1 and R1 detects the insertion of the conditional gene trap in Sec22b (tm1a). (c) PCR with primers F1 and R2 detects the excision of the conditional gene trap by FLP recombinase and distinguishes between Sec22bfl homozygous and heterozygous mice. (d) Competitive PCR with primers F1, F2, and R3 detects the excision of exon 3 of Sec22b and distinguishes between Sec22b− heterozygous and homozygous mice. (e) PCR on genomic DNA isolated from peripheral blood of a surviving Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre+ mouse and a Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre− littermate control, compared to DNA from Sec22b+/− mice. Gel images (b–e) are cropped. Full-length images may be found in Supplementary Fig. S1a–c.

Table 1.

Genotypic distribution of offspring from Sec22btm1a/+ and Sec22b+/− mating schemes.

| a. Genotype: | Sec22b +/+ | Sec22b tm1a/+ | Sec22b tm1a/ tm1a | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sec22b tm1a/+ × Sec22b tm1a/+ Expected Ratios | 25% | 50% | 25% | |

| At weaning (n = 73) | 33% (24) | 67% (49) | 0% (0) | <0.0001 |

| b. Genotype: | Sec22b +/+ | Sec22b +/− | p-value | |

| Sec22b +/− × Sec22b +/+ Expected Ratios | 50% | 50% | ||

| Weaning (n = 234) | 48% (113) | 52% (121) | 0.3237 | |

| c. Genotype: | Sec22b +/+ | Sec22b +/− | Sec22b −/− | p -value |

| Sec22b +/− × Sec22b +/− Expected Ratios | 25% | 50% | 25% | |

| Weaning (n = 34) | 24% (8) | 76% (26) | 0% (0) | <0.0001 |

| E13.5 (n = 9) | 22% (2) | 78% (7) | 0% (0) | 0.0751 |

| E11.5 (n = 21) | 24% (5) | 76% (16) | 0% (0) | 0.0024 |

| E9.5 (n = 20) | 25% (5) | 75% (15) | 0% (0) | 0.0032 |

| E8.5 (n = 35) | 34% (12) | 60% (21) | 6% (2) | 0.0033 |

| E7.5 (n = 23) | 13% (3) | 65% (15) | 22% (5) | 0.4685 |

| E3.5 (n = 33) | 27% (9) | 52% (17) | 21% (7) | 0.3938 |

(a) Genotypic distribution of offspring at weaning from Sec22btm1a/+ intercrosses with expected Mendelian distribution. (b) Genotypic distribution of offspring at weaning from Sec22b+/− × Sec22b+/+ crosses compared to expected Mendelian distribution. (c) Genotypic distribution of offspring at weaning and at indicated days post coitum (e.g. E13.5) from Sec22b+/− intercrosses as compared to expected Mendelian distribution. P-values are calculated from a one-tailed binomial test for (a, c) Sec22b−/− and for (b) Sec22b+/− versus all other genotypes.

Sec22b−/− mice do not survive beyond E8.5

To determine the stage at which germline loss of Sec22b results in embryonic death, we next performed timed matings on Sec22b+/− intercrosses. Offspring from this intercross exhibited Mendelian genotypic distribution at E3.5 (p = 0.6929) and E7.5 (p = 0.4685) (Table 1). However, at E8.5, Sec22b−/− mice were significantly underrepresented (p = 0.0055) (Table 1). Thereafter, at E9.5, E11.5, and E13.5, no Sec22b−/− embryos were observed (Table 1). Thus, Sec22b−/− embryos do not survive beyond E8.5.

Loss of Sec22b does not impact embryo size at E7.5

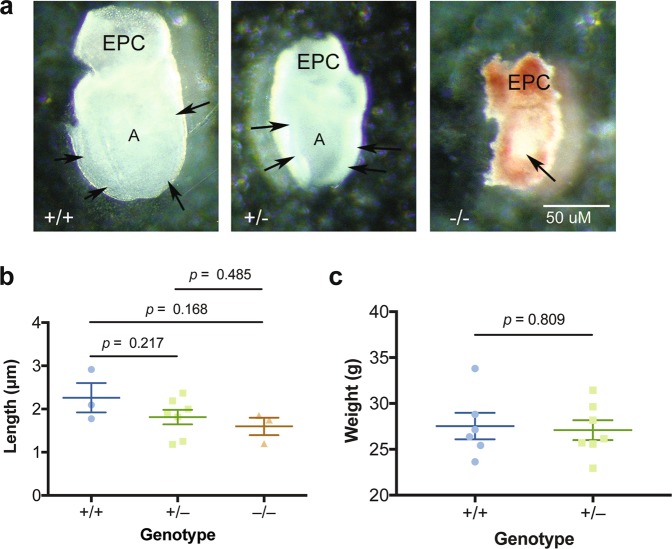

To attempt to investigate the mechanism driving the lethality we observed at E8.5 of Sec22b−/− embryos, we examined Sec22b−/− embryos one day earlier, at E7.5. At this stage, Sec22b+/− and Sec22b−/− embryos appeared smaller than Sec22b+/+ ones (Fig. 2a), though this trend did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2b). Notably, some Sec22b−/− embryos showed a developmental delay, appearing to be in the egg cylinder stage as opposed to the early somite stage (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Characterization of Sec22b+/− and Sec22b−/− mice. (a) Lateral views of embryos from the three genotypes. The ectoplacental cone (EPC) is located at the dorsal surface of the embryos. The +/+ (Sec22b+/+) embryo is beginning to convert to a primitive streak staged embryo, and is characterized by a well defined ectoderm (arrows) surrounding the expanded amniotic cavity, while the +/− (Sec22b+/−) embryo is at the late egg cylinder stage with a clear ectoderm layer and expanding amniotic cavity. The −/− (Sec22b−/−) embryo is surrounded by decidua and Reichert’s membrane, the ectoderm is just beginning to elongate to form the egg cylinder (arrow). (b) Length (μm) comparison between Sec22b+/+ (WT, n = 3), Sec22b+/− (Het, n = 7), Sec22b−/− (KO, n = 3) embryos using an unpaired two-tailed t test. Error bars represent SEM. (c) Weight in grams of 4.5–5 month old Sec22b+/− (n = 7) and Sec22b+/+ littermate controls (n = 6) mice using an unpaired two-tailed t test. Error bars represent SEM.

We hypothesized the impact of Sec22b heterozygosity on size required additional time to reach significance. Because Sec22b−/− mice die in utero, to address this, we compared weight of Sec22b+/− adult mice to littermate control wildtype mice. However, we did not observe a difference in size, suggesting that Sec22b heterozygosity does not impact growth (Fig. 2c).

Vav1-Cre driven deficiency of Sec22b results in embryonic lethality

SEC22B has a known role in immune cell function, particularly in mediating intracellular transport in myeloid cells2,9–13,16. Interestingly, defects in intracellular transport are known to cause lysosomal storage disorders in humans, which result in early mortality and notably can be treated with bone marrow transplantation22,23. Thus, we hypothesized that loss of Sec22b in the hematopoietic compartment would lead to embryonic lethality. To test this, we used Vav1-Cre to drive deletion of Sec22b in hematopoietic tissue. While Vav1-Cre also exhibits variable activity between 8–70% in endothelial cells, depending on anatomical location24, its excisional efficiency in endothelial tissue remains lower than that in hematopoietic cells25.

Using a Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre− breeding scheme, we observed a significantly reduced number of Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre mice at weaning (p < 0.0001) (Table 2). Additionally, we observed a trend towards fewer Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre+ and Sec22bfl/−; Vav1-Cre+ embryos at E12.5 (Table 2), one day after Vav1 expression begins26,27. To understand how loss of Sec22b in hematopoietic cells and endothelial cells might be causing embryonic lethality, we examined an E12.5 Sec22bfl/− Vav1-Cre+ embryo for evidence of dysfunction in hematopoietic organs where hematopoietic stem cells are found. Interestingly, in the liver, we observed enlarged endothelial-lined hepatic sinusoids and binucleate erythroid progenitors (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Genotypic distribution of offspring from Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre− mating pairs.

| a. Genotype: | Sec22b fl/ fl ; Vav1-Cre − | Sec22b fl/+ ; Vav1-Cre − | Sec22b fl/+ ; Vav1-Cre + | Sec22b fl/ fl ; Vav1-Cre + | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre− Expected Ratios | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | |

| Observed at weaning (n = 177) | 29% (52) | 29% (52) | 36% (64) | 5% (9) | <0.0001 |

| b. Genotype: | Sec22b fl/fl ; Vav1-Cre + | Sec22b fl/− ; Vav1-Cre + | All other genotypes | ||

| 1. Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/−; Vav1-Cre− Expected Ratios | 12.5% | 12.5% | 75% | ||

| E12.5 (n = 18) | 0% (0) | 11.1% (2) | 88.9% (16) | 0.1353 | |

| 2. Sec22b+/−; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre− Expected Ratios | 12.5% | 12.5% | 75% | ||

| E12.5 (n = 19) | 0% (0) | 3.0% (1) | 97.0% (18) | 0.0310 |

(a) Genotypic distribution of offspring at weaning from Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre− crosses as compared to expected Mendelian distribution. (b) Genotypic distribution of offspring at E12.5 from (1) Sec22bfl/+; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/−; Vav1-Cre− and (2) Sec22b+/−; Vav1-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre− crosses as compared to expected Mendelian distribution. P-values for (a) are calculated from a one-tailed binomial test for Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre+ versus all other genotypes. P-values for (b) are calculated from a one-tailed binomial test comparing the knockout embryos (both Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre+ and Sec22bfl/−; Vav1-Cre+) versus all other genotypes.

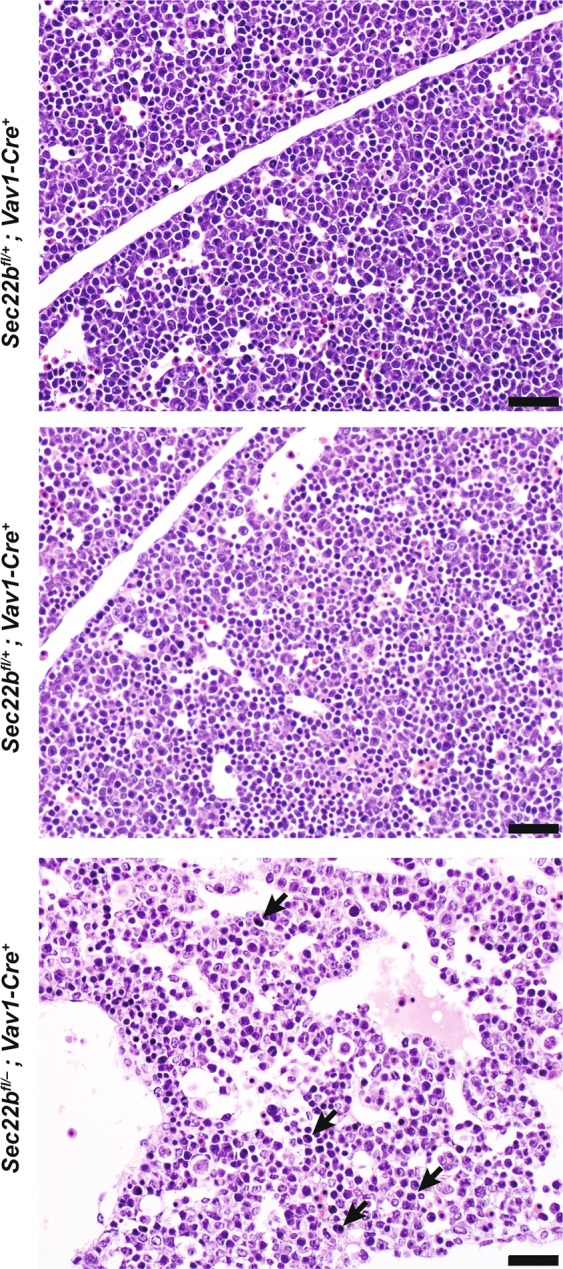

Figure 3.

Histopathologic characterization of Vav1-Cre mediated excision at E12.5. H&E visualization of E12.5 liver from Sec22bfl/− Vav1-Cre+ and Sec22bfl/+ Vav1-Cre− embryos with arrows indicating binucleate erythroid progenitors. Size bars all represent 20 μm.

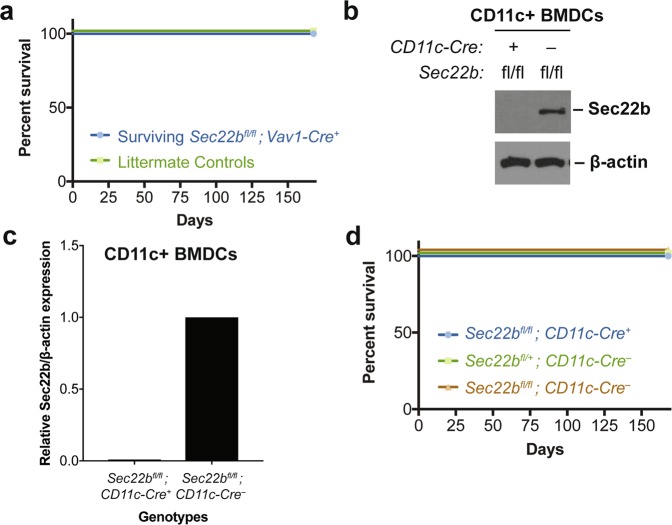

Finally, while some Vav1-Cre-mediated knockout embryos survived to weaning (Table 2), amplification of genomic DNA at the Sec22b locus in peripheral blood cells from these survivors (Fig. 1e) suggests that incomplete excision at exon 3 of Sec22b may explain survival to weaning and into adulthood (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

Survival of mice with Sec22b deletion in hematopoietic subsets. (a) 6 month survival curve for surviving Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre+ mice (n = 5) as compared to littermates (n = 4). (b) Western Blot and (c) corresponding quantification of CD11c + MACS-sorted BMDCs from Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre+ mice and Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre−. The Western Blot image (b) is cropped. Full-length images may be found in Supplementary Fig. S1d. (d) 6 month survival curve for Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre+ mice (n = 53) as compared to Sec22bfl/+; CD11c-Cre− (n = 52) and Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre− (n = 38) littermates.

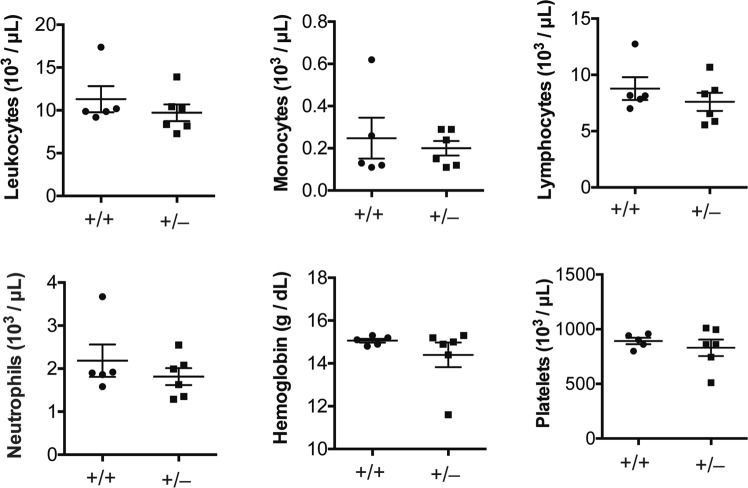

Sec22b+/− mice exhibit no hematopoietic phenotype under physiologic conditions

Because hematopoietic loss of Sec22b results in embryonic lethality (Table 2), we wondered if Sec22b+/− mice might exhibit a hematopoietic phenotype. To test this, we performed complete blood counts (CBCs) on peripheral blood collected from Sec22b+/− mice. These were indistinguishable from that obtained from littermate controls, including total white blood cells, monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, hemoglobin, and platelet counts (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Complete blood counts on Sec22b heterozygous mice. Total leukocytes, monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, hemoglobin, and platelets from peripheral blood of 5 month old Sec22b+/+ (n = 5) and Sec22b+/− (n = 6) littermates quantified as indicated on axes compared using unpaired two-tailed t tests. Error bars represent SEM.

Mice with Sec22b deletion in CD11c+ cells survive to adulthood

Given the embryonic lethality observed with Vav1-mediated deletion of Sec22b, the known role for SEC22B in macrophages10–13 and dendritic cells (DCs)2 in vitro, and the role of intracellular transport in lysosomal storage disorders23, we hypothesized loss of Sec22b in a myeloid cell population would result in embryonic lethality. To test this, we used Itgax-Cre (CD11c-Cre) to delete Sec22b in CD11c-expressing bone-marrow derived DCs (BMDCs) (Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre+) (Fig. 4b,c). To our surprise, offspring generated by crossing Sec22bfl/+; CD11c-Cre+ and Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre− mice exhibited the expected Mendelian distribution (Table 3) as well as normal survival up to 6 months (168 days) (Fig. 4d).

Table 3.

Genotypic distribution of offspring from Sec22bfl/+; CD11c-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre− mating pairs.

| Genotype: | Sec22b fl/ fl ; CD11c-Cre − | Sec22b fl/+ ; CD11c-Cre − | Sec22b fl/+ ; CD11c-Cre + | Sec22b fl/ fl ; CD11c-Cre + | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sec22bfl/+; CD11c-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre−Expected Ratios | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | |

| Observed at weaning (n = 606) | 28% (171) | 25% (149) | 22% (133) | 25% (153) | 0.4596 |

Genotypic distribution of offspring at weaning from Sec22bfl/+; CD11c-Cre+ × Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre− mating pairs as compared to expected Mendelian distribution. P-values are calculated from a one-tailed binomial test for Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre+ versus all other genotypes.

Discussion

Our studies demonstrate that Sec22b is required in vivo for survival past E8.5 (Table 1). While we observed normal development of Sec22b heterozygous adult mice (Fig. 2c), some null embryos demonstrated a developmental delay at E7.5 (Fig. 2a,b), though this did not reach statistical significance when assessed by embryonic length (Fig. 2b). Thus, the mechanism by which Sec22b is required for in vivo survival remains undefined.

Our data additionally demonstrate that deletion of Sec22b from the hematopoietic compartment also results in partial embryonic lethality (Table 2) and may cause abnormal erythropoiesis, based on preliminary histologic data (Fig. 3a). Further work is necessary to characterize the impact of Sec22b on embryonic hematopoiesis. Notably, Sec22b heterozygosity does not cause a hematopoietic phenotype under physiologic conditions (Fig. 5) and deletion of Sec22b within a specific hematopoietic subpopulation, CD11c-expressing cells, did not reproduce the embryonic lethality (Table 3, Fig. 4d). Interestingly, loss of Sec22b in this compartment does not seem to affect the development or function of CD11c+ cells28.

Vav1-Cre also exhibits recombination in endothelial cells, albeit less efficiently than in hematopoietic cells24. Thus it is possible that loss of Sec22b in endothelial cells may also drive lethality. Whether this is through their function as blood vessel endothelium or as progenitors of hematopoietic stem cells29 must be investigated in the future. The significance of altered hepatic sinusoidal morphology (Fig. 3) remains unclear. Interestingly, a recent study described a patient exhibiting growth delay, intellectual disability, hepatopathy, joint contracture and immunodeficiency with multiple homozygous recessive mutations, including in Sec22b30.

Taken together, our data suggest Sec22b is necessary in at least two cell compartments for embryonic survival: Vav1-expressing and non-expressing cells. Vav1 transcripts are first detectable at E11.526,27,31. By E12.5, there were reduced populations of Sec22fl/fl; Vav1-Cre+ and Sec22bfl/−; Vav1-Cre+ embryos (Table 2), which reached significance by weaning (Table 2), demonstrating the necessity of Sec22b expression in Vav1+ cells for embryonic survival. Furthermore, given that global deletion of Sec22b results in embryonic lethality by E8.5 (Table 1), Sec22b expression in another tissue compartment is also necessary for embryonic survival.

This Vav1-non-expressing cell compartment in which Sec22b expression is required for embryonic survival remains undefined. The loss of Sec22b−/− embryos at E8.5 could be due to the absence of Sec22b in the first wave of embryonic blood cells, which arise in the fetal yolk sac at E7.2532, or in another cell compartment. Sec22b has also previously been shown to be required in vitro for axonal growth in isolated mouse cortical neurons8 and for VLDL secretion in rat hepatocytes33, while in D. melanogaster, loss of Sec22 resulted in defects in eye development14. Furthermore, mutations to a SEC22B partner SNARE, GOSR2, have been associated with progressive myoclonic epilepsy5. Finally, SEC22B has also been implicated in pancreatic β-cell proinsulin secreation34. Future studies may explore how Sec22b expression in these tissues alters embryonic development and survival and may facilitate the development of clinically translatable models.

Methods

Mice

Mice with a FRT-flanked conditional gene trap inserted between exons 2 and 3 of Sec22b were obtained from the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Program (EUCOMM; Sec22btm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi) and crossed to mice with FLP recombinase expressed under the control of human β-actin promoter (005703, The Jackson Laboratory) to create the Sec22bfl allele. EIIa-Cre (003724, The Jackson Laboratory), Vav1-Cre (008610, The Jackson Laboratory), and CD11c-Cre transgenic mice (008068, The Jackson Laboratory), were bred to Sec22bfl/fl mice to create Sec22bfl/fl; EIIa-Cre+, Sec22bfl/fl; Vav1-Cre+, Sec22bfl/fl; CD11c-Cre+ mice. Mice acquired from Jackson Laboratory had been backcrossed to the C57/BL6 background as described in their catalog. Mice acquired from EUCOMM were generated using the C57/BL6 background. All animals were cared for under regulations reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, based on University Laboratory Animal Medicine guidelines.

Timed matings

Breeding pairs were co-housed in the evening. Females were checked for the presence of a vaginal plug the following morning (0.5 days post coitum; E0.5). Those with plugs were tracked and euthanized at the appropriate time point and embryos were dissected from uteri and, where indicated, photographed prior to fixation.

DNA Isolation

Weaned mice and adult mice were genotyped by digesting tail clips in 200 uL/tail clip DirectPCR Lysis Reagent (Mouse Tail) (Viagen, 102-T) and 4 uL/tail clip Proteinase K (Sigma Aldrich, P4850) at 56 °C overnight followed by denaturing at 95 °C for 1 hour. Genomic DNA from embryos aged E7.5–13.5 and from peripheral blood was obtained using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, 69504), following manufacturer’s instructions. E3.5 blastocysts were harvested into 1xPBS into PCR tubes (USA Scientific, 1402–2500), frozen at −80 °C, and then thawed. Thawed product was used for genotyping PCR.

Primers and genotyping

Primers used to genotype Cre transgenes and the Sec22b allele are collected in Table 4. Binding locations for the Sec22b primers are identified in Fig. 1a. The Sec22b F1 + R1 primers was used to identify gene-trapped mice and the Sec22b F1 + R2 primers was used to identify floxed versus wildtype mice. Sec22b F1, F2, R3 were used in a competitive PCR to identify the null allele versus the floxed allele. Genotyping was performed via PCR reaction with GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, M7122) according to manufacturer’s recommendations.

Table 4.

Primers used for Sec22b and Cre genotyping. Sec22b primers include F1 and F2 forward primers and R1, R2, and R3 reverse primers. Sec22b primer binding positions are indicated in Fig. 1a. Cre primers detect both EIIa- and CD11c-Cre transgenes. Used together, Vav1 primers detect the Vav1-Cre transgene.

| Primer Name | Sequence (5′→3′) |

|---|---|

| Sec22b F1 | AAGGGTGGATGGATTCTTCACAC |

| Sec22b F2 | TCCTTTTGAATGGAGAAAGCTTC |

| Sec22b R1 | TTGGTGGCCTGTCCCTCTCACCTT |

| Sec22b R2 | GCAGCTCAGCAGTAAGAACACGTC |

| Sec22b R3 | CCTGTGACAGTCTACAGATTGGA |

| Cre F | TTACCGGTCGATGCAACGAGT |

| Cre R | TTCCATGAGTGAACGAACCTGG |

| Vav1 F1 | AGATGCCAGGACATCAGGAACCTG |

| Vav1 R1 | ATCAGCCACACCAGACACAGAGATC |

| Vav1 F2 | CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT |

| Vav1 R2 | GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATC |

Gels were imaged using AlphaImager HP. Resulting images were processed using AutoContrast.

Imaging and analysis

Embryos were dissected and imaged by light microscopy (Leica, DM IRB). ImageJ was used to calculate the surface area of photographed embryos. Images were prepared with Adobe Photoshop CS6, using the AutoContrast and AutoTone features and by setting the gamma correction to 0.5.

Histologic methods

E12.5 embryos were embedded in OCT compound and frozen. Sections were then placed on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Western blot

Whole cell lysates were obtained and protein concentrations determined by BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific, 23225). Protein was separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, IPVH00010) using a Bio-Rad semi-dry transfer cell (1703940) (20 V, 1 h). Blots were incubated with SEC22B (1:200, Santa Cruz, 29-F7) and b-Actin (1:1000, abcam, ab8226) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Incubation with secondary anti-mouse antibody conjugated to HRP (1:10,000, Santa Cruz, sc-2005) was performed for 1 hour at room temperature. Bound antibody was revealed using SuperSignal ECL substrate (Thermo Scientific). Conversion to grayscale and densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ.

Complete blood counts

Peripheral blood was collected into K2 EDTA-coated Microvette collection tubes (Sarstedt, 16.444.100). CBCs were performed with a HEMAVet950 (Drew Scientific, CT) at the University of Michigan In Vivo Animal Core.

Statistics

All statistical analysis was performed using Graphpad Prism 7. Specific tests are indicated in the respective figure legends.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants HL-128046, HL-090775, CA-173878, CA-203542, R35-HL135793, K08 HL128794, and the Herman and Dorothy Miller Fund. We acknowledge the In Vivo Animal Core at the University of Michigan for their technical expertise. Rami Khoriaty is a recipient of the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award. David Ginsburg is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.W., R.K., K.S.O., D.G., P.R.; Methodology, S.J.W., R.K., K.S.O., G.Z., M.H. Validation, S.J.W., R.K., S.H.K., K.S.O., G.Z., M.H. Formal analysis, S.J.W., K.S.O., M.H. Investigation, S.J.W., R.K., S.H.K., K.S.O., G.Z., M.H., C.Z., K.O.W., T.T., Y.S. Resources, R.K., D.G. Writing—Original Draft, S.J.W. Writing—Review & Editing, S.J.W., R.K., K.S.O., M.H., D.G., P.R. Visualization, S.J.W. Supervision, R.K., D.G., P.R. Funding Acquisition, S.J.W., P.R.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article or in Supplementary Information.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-46536-7.

References

- 1.Chen YA, Scheller RH. SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:98–106. doi: 10.1038/35052017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cebrian I, et al. Sec22b regulates phagosomal maturation and antigen crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2011;147:1355–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang T, Wong SH, Tang BL, Xu Y, Hong W. Morphological and functional association of Sec22b/ERS-24 with the pre-Golgi intermediate compartment. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:435–453. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu D, Joglekar AP, Williams AL, Hay JC. Subunit structure of a mammalian ER/Golgi SNARE complex. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39631–39639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volker JM, et al. Functional assays for the assessment of the pathogenicity of variants of GOSR2, an ER-to-Golgi SNARE involved in progressive myoclonus epilepsies. Dis Model Mech. 2017;10:1391–1398. doi: 10.1242/dmm.029132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Castillo MD, et al. Retrograde transport is not required for cytosolic translocation of the B-subunit of Shiga toxin. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:2373–2387. doi: 10.1242/jcs.169383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki T, Kojima M, Tani K, Tagaya M. Sec22b-dependent assembly of endoplasmic reticulum Q-SNARE proteins. Biochem J. 2008;410:93–100. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petkovic Maja, Jemaiel Aymen, Daste Frédéric, Specht Christian G., Izeddin Ignacio, Vorkel Daniela, Verbavatz Jean-Marc, Darzacq Xavier, Triller Antoine, Pfenninger Karl H., Tareste David, Jackson Catherine L., Galli Thierry. The SNARE Sec22b has a non-fusogenic function in plasma membrane expansion. Nature Cell Biology. 2014;16(5):434–444. doi: 10.1038/ncb2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arasaki K, Roy CR. Legionella pneumophila promotes functional interactions between plasma membrane syntaxins and Sec22b. Traffic. 2010;11:587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01050.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arasaki K, Toomre DK, Roy CR. The Legionella pneumophila effector DrrA is sufficient to stimulate SNARE-dependent membrane fusion. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canton J, Ndjamen B, Hatsuzawa K, Kima PE. Disruption of the fusion of Leishmania parasitophorous vacuoles with ER vesicles results in the control of the infection. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:937–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatsuzawa K, et al. Sec22b is a negative regulator of phagocytosis in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4435–4443. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuaita BH, Burkholder KM, Boles BR, O’Riordan MX. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Sensor Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1alpha Augments Bacterial Killing through Sustained Oxidant Production. MBio. 2015;6:e00705. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00705-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X, et al. Sec. 22 regulates endoplasmic reticulum morphology but not autophagy and is required for eye development in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:7943–7951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.640920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nair U, et al. SNARE proteins are required for macroautophagy. Cell. 2011;146:290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura T, et al. Dedicated SNAREs and specialized TRIM cargo receptors mediate secretory autophagy. EMBO J. 2017;36:42–60. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renna M, et al. Autophagic substrate clearance requires activity of the syntaxin-5 SNARE complex. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:469–482. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko MS, et al. Large-scale cDNA analysis reveals phased gene expression patterns during preimplantation mouse development. Development. 2000;127:1737–1749. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carninci P, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the mammalian genome. Science. 2005;309:1559–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1112014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hay JC, Chao DS, Kuo CS, Scheller RH. Protein Interactions Regulating Vesicle Transport between the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Golgi Apparatus in Mammalian Cells. Cell. 1997;89:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maguire S, et al. Targeting of Slc25a21 is associated with orofacial defects and otitis media due to disrupted expression of a neighbouring gene. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoogerbrugge PM, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for lysosomal storage diseases. The European Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation. Lancet. 1995;345:1398–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92597-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Platt FM. Sphingolipid lysosomal storage disorders. Nature. 2014;510:68–75. doi: 10.1038/nature13476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inra CN, et al. A perisinusoidal niche for extramedullary haematopoiesis in the spleen. Nature. 2015;527:466–471. doi: 10.1038/nature15530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Boer J, et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:314–325. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zmuidzinas A, et al. The vav proto-oncogene is required early in embryogenesis but not for hematopoietic development in vitro. EMBO J. 1995;14:1–11. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb06969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bustelo XR, Rubin SD, Suen KL, Carrasco D, Barbacid M. Developmental expression of the vav protooncogene. Cell Growth Differ. 1993;4:297–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu SJ, et al. A Critical Analysis of the Role of SNARE Protein SEC22B in Antigen Cross-Presentation. Cell Rep. 2017;19:2645–2656. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eilken HM, Nishikawa S, Schroeder T. Continuous single-cell imaging of blood generation from haemogenic endothelium. Nature. 2009;457:896–900. doi: 10.1038/nature07760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diao H, Zhu P, Dai Y, Chen W. Identification of 11 potentially relevant gene mutations involved in growth retardation, intellectual disability, joint contracture, and hepatopathy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e13117. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller G, Kennedy M, Papayannopoulou T, Wiles MV. Hematopoietic commitment during embryonic stem cell differentiation in culture. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:473–486. doi: 10.1128/MCB.13.1.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palis J, Robertson S, Kennedy M, Wall C, Keller G. Development of erythroid and myeloid progenitors in the yolk sac and embryo proper of the mouse. Development. 1999;126:5073–5084. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddiqi S, Mani AM, Siddiqi SA. The identification of the SNARE complex required for the fusion of VLDL-transport vesicle with hepatic cis-Golgi. Biochem J. 2010;429:391–401. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan J, et al. cTAGE5 deletion in pancreatic beta cells impairs proinsulin trafficking and insulin biogenesis in mice. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:4153–4164. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201705027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article or in Supplementary Information.