Abstract

Linkage isomers of reduced metal-nitrosyl complexes serve as key species in nitric oxide (NO) reduction at monometallic sites to produce nitrous oxide (N2O), a potent greenhouse gas. While factors leading to extremely rare side-on nitrosyls are unclear, we describe a pair of nickel-nitrosyl linkage isomers through controlled tuning of noncovalent interactions between the nitrosyl ligands and differently encapsulated potassium cations. Furthermore, these reduced metal-nitrosyl species with N-centered spin density undergo radical coupling with free NO and provide a N–N coupled cis-hyponitrite intermediate whose protonation triggers the release of N2O. This report outlines a stepwise molecular mechanism of NO reduction to form N2O at a mononuclear metal site that provides insight into the related biological reduction of NO to N2O.

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a long-lived (ca. 114 years) greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 298 times that of CO2 on a molecular basis.1 Enhanced through feeding of crops with nitrogen-rich fertilizers,2 global emission of N2O is mainly attributed to the microbial and fungal denitrification processes mediated by metalloenzymes.3 The most critical step for N2O generation is N–N bond formation that occurs via the reductive coupling of two nitric oxide (NO) molecules. This takes place at diiron sites of nitric oxide reductase (NOR) enzymes4 as well as at mononuclear sites in the iron-based cytochrome P450 nitric oxide reductase (NOR)5 or copper nitrite reductase (CuNiR)6 enzymes (Figure 1a). Based on numerous theoretical studies, it seems likely that an intermediate hyponitrite species (N2O22−) precedes N2O release.7 For instance, coupling of two metal-nitrosyl [M]-NO moieties takes place upon reduction of [(TpRuNO)2(μ-Cl)(μ-Pz)]2+ to afford the N–N reductively coupled product (TpRu)2(μ-Cl)(μ-Pz){μ-κ2-N(=O)N(=O)}.8 Reductive coupling of NO at copper(I) complexes has led to dinuclear trans-hyponitrite copper(II) complexes [CuII]2(μ-O2N2) that release N2O either upon acidification9 or thermal decay;10 the later also produces [CuII](NO2) via disproportionation.10 The nickel nitrosyl [(bipy)(Me2phen)NiNO][PF6] mediates NO disproportionation in the presence of NO and yields N2O via a mononuclear cis-hyponitrite [Ni](κ2-O2N2).11 The factors that lead to N–N bond formation at a monometallic site, however, have not been explicitly documented.12

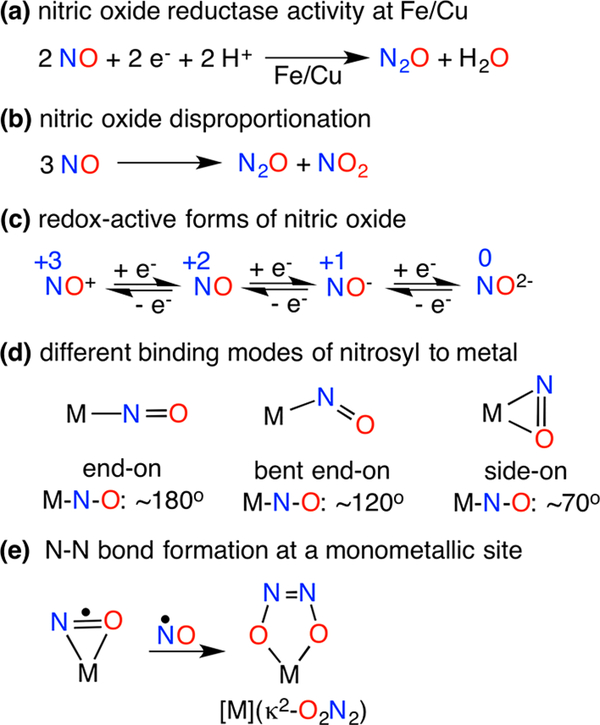

Figure 1.

Reactivity and binding of nitrosyl ligands at transition metal sites.

We hypothesize that the presence of spin density at the N atom of a metal-nitrosyl [M]-NO, perhaps enhanced by the ability to achieve a side-on [M]-NO conformation, may facilitate N–N bond formation between a metal-nitrosyl and nitric oxide to give cis-hyponitrites [M](κ2-O2N2) (Figure 1e). Access to side-on [M](η2-NO) complexes may both expose the N atom for N–N coupling and initiate a M-O interaction prior to forming mononuclear [M](κ2-O2N2) complexes. Such side-on conformations are known in the photoexcited states of {Ni(NO)}10 complexes13 where the superscript in the Enemark–Feltham formulation {Ni(NO)}10 represents the total number of metal d and NO π* electrons.14 The side-on binding of a nitrosyl ligand (Figure 1d) in a mononuclear synthetic complex, however, has not been observed in its ground state. {[(Me3Si)2N]2(THF)Y}2(μ-η2:η 2-NO) is a singular example that possesses a side-on NO achieved via bridging between two transition or rare earth metal centers that possesses a highly reduced NO2− ligand.15 Crystallographic studies revealed side-on η2-NO binding in fully reduced bovine cytochrome c oxidase (CcO)16 and copper nitrite reductase (CuNiR)17 that feature mononuclear {Cu-(NO)}11 sites, though solution spectroscopic studies suggest end-on binding.18,19 DFT calculations for both side-on and end-on {Cu(NO)}11 species suggest that each possesses a CuI(·NO) electronic formulation20 with a considerable amount of spin density at the nitrosyl N atom, reinforced by EPR studies of the reduced {Cu(NO)}11 intermediate of CuNIR.18,21 Furthermore, differential H-bonding and/or steric interactions from second-sphere protein residues may play a vital role in the determining the conformation of {Cu(NO)}11 species.21,22

To synthetically outline factors that control metal-nitrosyl bonding modes and NO coupling reactivity, we targeted low coordinate {M(NO)}10/11 pairs that could accommodate both side-on NO and cis-hyponitrite ligands (Figure 1d,e). The salt metathesis reaction between equimolar amounts of the β-diketiminato potassium salt [iPr2NNF6]K(THF) and (THF)2Ni(NO)I in tetrahydrofuran (THF) affords the diamagnetic {Ni(NO)}10 complex [iPr2NNF6]NiNO (1) isolated as dark green crystals in 76% yield (Figure 2a). The X-ray structure of 1 reveals a trigonal-planar Ni center with an end-on nitrosyl ligand (Nil–N3–O1 = 174.47(11)°) with a N3–O1 distance of 1.1602(15) Å (Figure S22). The infrared spectrum of 1 indicates a nitrosyl stretch ((νNO) at 1825 cm−1, similar to values reported for other three-coordinate neutral nickel-nitrosyl complexes (νNO = 1817–1779 cm−1).23 Notably, the cyclic voltammogram of 1 in tetrahydrofuran at room temperature exhibits a reversible reduction wave centered at −1.89 V (vs ferrocenium/ferrocene), attributed to the {Ni(NO)}10/11 redox couple (Figure S6).

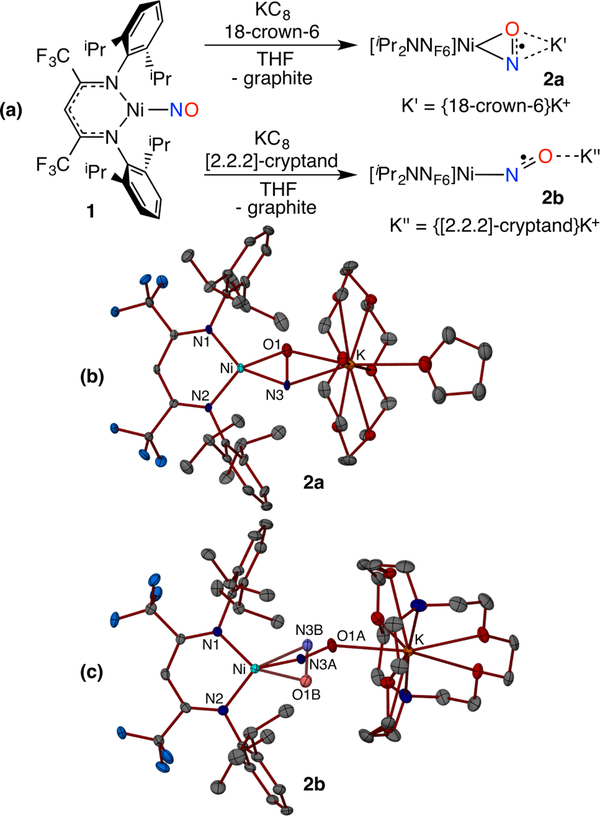

Figure 2.

Synthesis (a) and X-ray structures (b,c) of {NiNO}11 anions 2a (side-on) and 2b (77/23 end-on/side-on).

One-electron reduction of the {Ni(NO)}10 complex 1 with potassium-graphite (KC8) (1.2 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran in the presence of 18-crown-6 (1 equiv) leads to a rapid color change from green to purple (Figure 2a). Single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of the purple complex 2a reveals two independent [iPr2NNF6]Ni(μ-η2: η2-NO)K(18-crown-6)(THF) moieties. Each nickel exhibits square planar coordination that features a side-on NO ligand between the Ni and K centers. Although disorder from interchange of N/O positions precludes a detailed assessment of metrical parameters, refinement of the NO ligand into a single orientation (Figure 2b) gives short Ni–N (1.853(5) Å; 1.866(5) Å) and Ni–O (1.839(5) Å; 1.868(5) Å) distances similar to those observed in a related [Ni](η2-ONPh) complex.24 The nitrosyl ligand in the {Ni(NO)}11 species 2a (molecule 1: 1.270(6) Å; molecule 2: 1.284(6) Å) is significantly more activated than in the {Ni(NO)}10 analogue 1 (1.1602(15) Å), despite N/O positional disorder that likely underestimates the N–O distance.15 Disorder models that allow pairs of N/O atoms to refine lead to slightly longer N–O distances of 1.28–1.32 Å but with a wider spread of Ni–N/O distances (Figure S23c,d). Thus, 2a possesses a nitrosyl ligand with a N–O distance longer than in most metal-nitrosyls25 except {[(Me3Si)2N]2(THF)Y}2(,M-η2:η2-NO), which also features a side-on NO ligand (N–O: 1.390(4)Å).15 Coordination of the potassium cation to both the nitrogen and oxygen atoms of the reduced nitrosyl ligand in the {[Ni](η2-NO)}− anion of 2a gives K–N/O distances in the range 2.826(5) Å - 2.869(5) Å that leads to Ni···K separations of 4.417 Å (molecule 1) and 4.467 Å (molecule 2). The infrared spectra of two isotopologues 2a and 2a-15N exhibit 14N/15N isotope sensitive bands at 894 and 878 cm−1, respectively. This is the lowest νNO reported for a transition metal nitrosyl complex, lower than 951 cm−1 in {[(Me3Si)2N]2(THF)Y}2(μ-η2:η2-NO).15

More completely encapusulating the K+ cation changes the nitrosyl bonding mode of the {[Ni](NO)}− anion. Reduction of [iPr2NNF6]NiNO (1) with KC8 (1.2 equiv) in the presence of [2.2.2]-cryptand (1 equiv) in tetrahydrofuran gives [iPr2NNF6]Ni(μ-NO)K[2.2.2-cryptand] (2b) (Figures 2c, S24). By significantly lengthening the Ni···K separation (5.466 Å), the nitrosyl ligand exhibits both linear (77%) and side-on (23%) conformations in the solid state. The linear NO ligand (Ni1–N3A–O1A, 165.8(3)°) in 2b is more highly reduced than in 1 with a N–O distance of 1.198(4) Å. The minor side-on conformer exhibits N/O positional disorder whose principle component possesses a N–O distance of 1.274(19) Å similar to 2a. The IR spectrum of a solid sample of 2b reveals an NO stretch at 1555 cm−1 (1525 cm−1 for 2b-15NO) that is consistent with a highly reduced linear NO ligand (Figure S10).25

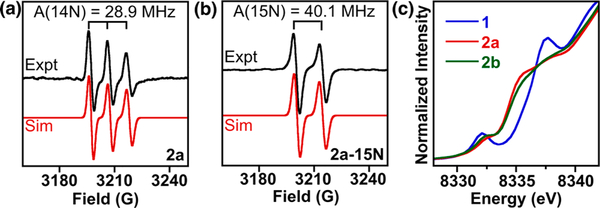

The room temperature EPR spectrum of [iPr2NNF6]Ni(μ-η2:η2-NO)K[18-crown-6](THF) (2a) in tetrahydrofuran indicates a S = 1/2 species with a giso value of 2.0008, very close to that of the free electron (ge = 2.0023). This three line spectrum of 2a is due to strong coupling with the 14N nucleus of the bound NO ligand (A14N = 28.9 MHz), which shifts to a two line pattern for 2a-15N (A15N = 40.1 MHz) (Figure 3a,b). These data are very similar to the highly reduced, radical NO2− dianion in {[(Me3Si)2N]2(THF)Y}2(μ-η2:η2-NO).15 In both THF solution and frozen glass (20 K), EPR spectra of 2a and 2b are nearly indistinguishable (Figures S20 and S21). Modeling of the low T EPR spectra of 2a was guided by DFT calculations and required the use of two separate components, suggesting that THF solutions of 2a and 2b may contain a mixture of side-on and linear nitrosyls.

Figure 3.

(a, b) X-band EPR spectra (black trace) of 2a and 2a-15N in tetrahydrofuran at 293 K. Simulations (red trace) provide giso = 2.0008, Aiso(14N) = 28.9 MHz (for 2a), and Aiso(15N) = 40.1 MHz (for 2a-15N). (c) Ni K-edge X-ray absorption spectra of 1, 2a, and 2b.

Ni K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) probes the Ni oxidation state by exciting a Ni 1s electron to valence Ni 3d orbitals (pre-edge, ~8330–8335 eV) and Ni 4p orbitals (edge, >8345 eV) (Figure 3c). The pre-edge features of 1 (8332.1(0) eV), 2a (8332.3(1) eV), and 2b (8332.3(0) eV) are at a similar energy to the closely related NiII complex [iPr2NNF6]NiII(μ-Br)2Li(THF)2, (8331.6 eV),24 suggesting that complexes 1, 2a, and 2b are best described as NiII, with the slight shift to higher pre-edge energies attributed to NO backbonding. Calculated TDDFT XAS assign the rising edge feature in 2a and 2b at ~8335 eV is a Ni to ligand π*transition that has much weaker intensity in 1 (Figure S38). These results suggest that reduction of {Ni(NO)}10 species 1 to anionic {Ni(NO)}11 species 2a and 2b occurs primarily at the NO ligand. Complexes 2a (side-on) and 2b (principally end-on) have nearly identical XAS spectra and cannot be readily distinguished by this technique.

DFT calculations (Supporting Information) provide insight into electronic structure of the NO complexes and the secondary sphere interactions that control the NO bonding mode. DFT geometry optimizations of 1, 2a, and 2b without counterions using the ORCA program26 (B3LYP, TZVP/SV(P)) reveal spin density at the NO ligand in the 2a side-on (1.25 e−) and 2b end-on conformations (1.52 e−) that are almost identical in energy. Similar to TpNiNO with a linear NO ligand,27 complex 1 is best described as high spin Ni(II) antiferromagnetically coupled to NO1− while the anionic complexes 2a and 2b are low spin Ni(II) with an NO2− ligand (Figures S33 and S35). Full molecule calculations could energetically distinguish the end-on and side on conformations by fixing the Ni···K distance to 5.466 Å. This revealed the side-on conformation to be only 2.3 kcal/mol more stable, consistent with the linear/side-on disordered observed in the solid state structure of 2b.

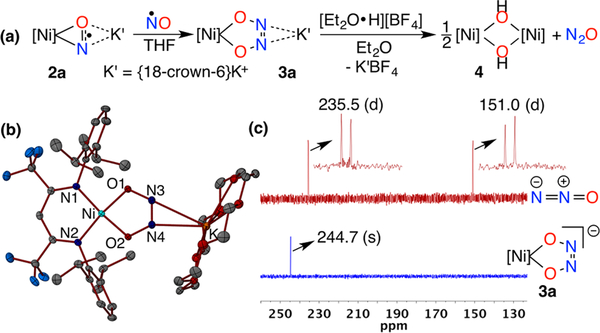

The reduced NO ligands that bear significant unpaired electron density in 2a and 2b are primed for coupling with •NO to form cis-hyponitrite ligands in complexes {[Ni](κ 2-O2N2)}− (3a and 3b). Addition of 1 equiv NO(g) to 2a in tetrahydrofuran at room temperature affords diamagnetic {[iPr2NNF6]Ni(κ 2-O2N2)}K(18-crown-6) (3a) in 72% yield (Figure 4a). X-ray diffraction analysis of 3a reveals a square planar Ni center with short Ni–Nβ-dik 1.8895(15), 1.8936(15) Å and Ni–O 1.8241(13), 1.8187(13) Å) distances clearly indicating coupling between the two NO ligands (N3–N4 = 1.235(2) Å) (Figures 4b and S25). The cis-hyponitrite ligand exhibits an otherwise symmetric structure (O1–N3 = 1.370(2), O2–N4 = 1.367(2) Å) similar to those previously observed12 despite unsymmetrical coordination of {K[18-crown-6]}+ cation to both the N atoms of the hyponitrite ligand (K1–N4, 2.7519(17), K1–N3, 3.0584(18) Å). Addition of NO to 2b similarly provides {[iPr2NNF6]Ni(κ2-O2N2)}K[2.2.2-cryptand] (3b) in 89% yield with very similar metrical parameters for the {[Ni](κ2-O2N2)}− moiety that is coordinated to only one cis-hyponitrite N atom by the {K[2.2.2-cryptand]}+ cation (K–N = 3.274 Å) (Figure S26). Capture of NO by a reduced NO ligand in {[Ni](NO)}− to form cis-hyponitrites {[Ni](κ2-O2N2)}− mirrors the reactivity of NO with [iPr2NNF6]Ni(η2-ONPh) to form [iPr2NNF6]Ni-(η2-O2N2Ph). In both anionic {[Ni](NO)}− and neutral [Ni](η2-ONPh), there is significant unpaired electron density at the reduced NO moiety.24 Notably, the {Ni(NO)}10 complex 1 does not react with nitric oxide.

Figure 4.

(a) Formation of cis-hyponitrite intermediate 3a and its transformation to nitrous oxide. (b) X-ray crystal structure of 3a. (c) Comparison of 15N NMR spectra (41 MHz, 298 K, tetrahydrofuran-d8) of [Ni](κ2-O215N2)K[18-crown-6] (3a-15N15N) (blue trace) and the crude reaction mixture (red trace) obtained upon addition of 1 equiv trifluoroacetic acid to a solution of 3a-15N15N in tetrahydrofuran-d8.

NMR spectra of {[iPr2NNF6]Ni(κ2-O2N2)}K[18-crown-6] (3a) in THF-d8 exhibits sharp resonances characteristic of diamagnetic β-diketiminato NiII complexes (Figures S12–S14).24 Notably, the 15N NMR spectrum of a 15N enriched sample of 3a (3a-15N15N) in THF-d8 shows a sharp singlet at 244.7 ppm (vs liquid NH3) indicating symmetric κ2-O,O binding of the hyponitrite ligand to the [iPr2NNF6]Ni core in solution at room temperature. The {[iPr2NNF6]Ni(κ2-O2N2)}− anion in 3b exhibits identical NMR features as found in 3a.

Hyponitrite complexes are known to release N2O upon heating or protonation.9,10,12 The {[iPr2NNF6]Ni(κ2-O2N2)}− anion (in 3a or 3b) is thermally stable up to 60 °C with no evidence of N2O loss. Protonation of 3a or 3b by 1 equiv trifluoroacetic acid, however, triggers the instantaneous release of N2O observed by 15N NMR (Figures 4c and S17) and IR spectroscopy (2227 cm−1) (Figure S16). Protonation with HBF4·OEt2 produces N2O in 76% yield and allows for isolation of the nickel(II) hydroxide dimer {[iPr2NNF6]Ni}2(μ-OH)2 (4) in 66% yield that exhibits a structure similar to other β-diketiminato [NiII]2(μ-OH)2 complexes (Figure S27).28

Spectroscopic and computational insights reveal that one-electron reduction of the {Ni(NO)}10 complex 1 largely takes place at the NO ligand, leading to side-on and end-on {Ni(NO)}11 species 2a and 2b, respectively. Regardless of the nitrosyl binding mode, these {Ni(NO)}11 complexes possess a significant amount of unpaired electron density at the nitrosyl N atom and undergo facile coupling with NO to give the cis-hyponitrite {[Ni](κ2-O2N2)}−, which releases N2O upon protonation. Controlled tuning of the second coordination sphere interactions between the nitrosyl ligand of the {Ni(NO)}11 anion and a potassium cation modifies the metal-nitrosyl bonding mode, favoring side-on [M](η2-NO) at shorter Ni···K distances. Especially because the corresponding {Ni(NO)}10 species does not react with NO, these findings underscore electronic and conformational factors that favor NO coupling via N–N bond formation at monometallic sites. Separation of NO-based reduction and NO coupling steps provides important context for the biologically important reduction of NO that results in N2O formation via protonation of cis-hyponitrite intermediates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T.H.W. acknowledges the NSF (CHE-1459090), the NIH (R01GM126205), and the Georgetown Environment Initiative. S.C.E.S. acknowledges the CPP College of Science, a CSUPERB New Investigator Grant, and NSF XSEDE (CHE160059). S.A.K. acknowledges the Heavy Element Chemistry Program by the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES), U.S. Department of Energy, and Seaborg Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship (S.C.E.S.). LANL is operated by Los Alamos National Security, LLC, for the National Nuclear Security Administration of U.S. DOE (DE-AC52-06NA25396). Use of Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light source, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, supported by DOE, Office of Science, BES (DE-AC02-76SF00515).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b09769.

Experimental, characterization, and computational details (PDF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 1 (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 2a (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 2b (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 3a (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 3b (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 4 (CIF)

NOTE ADDED IN PROOF

Coupling of NO at a dinickel complex to form a dinuclear cis-hyponitrite has been reported while this manuscript was under review.29

REFERENCES

- (1).Ravishankara AR; Daniel JS; Portmann RW Nitrous Oxide (N2O): The Dominant Ozone-Depleting Substance Emitted in the 21st Century. Science 2009, 326, 123–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Reay DS; Davidson EA; Smith KA; Smith P; Melillo JM; Dentener F; Crutzen PJ Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Thomson AJ; Giannopoulos G; Pretty J; Baggs EM; Richardson DJ Biological sources and sinks of nitrous oxide and strategies to mitigate emissions. Philos. Trans. R Soc., B 2012, 367, 1157–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Shiro Y; Sugimoto H; Tosha T; Nagano S; Hino T Structural Basis for Nitrous Oxide Generation by Bacterial Nitric Oxide Reductases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B 2012, 367, 1195–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).McQuarters AB; Wirgau NE; Lehnert N Model Complexes of Key Intermediates in Fungal Cytochrome P450 Nitric Oxide Reductase (P450nor). Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2014, 19, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Merkle AC; Lehnert N Binding and Activation of Nitrite and Nitric Oxide by Copper Nitrite Reductase and Corresponding Model Complexes. Dalton Trans 2012, 41, 3355–3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).(a) Blomberg MRA; Siegbahn PEM Mechanism for N2O Generation in Bacterial Nitric Oxide Reductase: A Quantum Chemical Study. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 5173–5186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Metz S N2O Formation via Reductive Disproportionation of NO by Mononuclear Copper Complexes: A Mechanistic DFT Study. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 3820–3833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Suzuki T; Tanaka H; Shiota Y; Sajith PK; Arikawa Y; Yoshizawa K Proton-Assisted Mechanism of NO Reduction on a Dinuclear Ruthenium Complex. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 7181–7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Arikawa Y; Asayama T; Moriguchi Y; Agari S; Onishi M Reversible N-N Coupling of NO Ligands on Dinuclear Ruthenium Complexes and Subsequent N2O Evolution: Relevance to Nitric Oxide Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 14160–14161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lionetti D; de Ruiter G; Agapie T A Trans-Hyponitrite Intermediate in the Reductive Coupling and Deoxygenation of Nitric Oxide by a Tricopper-Lewis Acid Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5008–5011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wijeratne GB; Hematian S; Siegler MA; Karlin KD Copper(I)/NO(g)Reductive Coupling Producing a Trans-Hyponitrite Bridged Dicopper(II) Complex: Redox Reversal Giving Copper-(I)/NO(g)Disproportionation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 13276–13279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Wright AM; Zaman HT; Wu G; Hayton TW Mechanistic Insights into the Formation of N2O by a Nickel Nitrosyl Complex. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 3108–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).(a) Wright AM; Hayton TW Understanding the Role of Hyponitrite in Nitric Oxide Reduction. Inorg. Chem 2015, 54, 9330–9341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arikawa Y; Onishi M Reductive N-N Coupling of NO Molecules on Transition Metal Complexes Leading to N2O. Coord. Chem. Rev 2012, 256, 468–478. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Fomitchev DV; Furlani TR; Coppens P Combined X-Ray Diffraction and Density Functional Study of [Ni(NO)(η5-Cp*)] in the Ground and Light-Induced Metastable States. Inorg. Chem 1998, 37, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Enemark JH; Feltham RD Principles of Structure, Bonding, and Reactivity for Metal Nitrosyl Complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev 1974, 13, 339–406. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Evans WJ; Fang M; Bates JE; Furche F; Ziller JW; Kiesz MD; Zink JI Isolation of a radical dianion of nitrogen oxide (NO)2−. Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Ohta K; Muramoto K; Shinzawa-Itoh K; Yamashita E; Yoshikawa S; Tsukihara T X-Ray Structure of the NO-Bound CuB in Bovine Cytochrome c Oxidase. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun 2010, 66, 251–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Tocheva EI; Rosell FI; Mauk AG; Murphy MEP Side-on Copper-Nitrosyl Coordination by Nitrite Reductase. Science 2004, 304, 867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Usov OM; Sun Y; Grigoryants VM; Shapleigh JP; Scholes CP EPR-ENDOR of the Cu(I)NO Complex of Nitrite Reductase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 13102–13111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fujisawa K; Tateda A; Miyashita Y; Okamoto K; Paulat F; Praneeth VKK; Merkle A; Lehnert N Structural and Spectroscopic Characterization of Mononuclear copper(I) Nitrosyl Complexes: End-on versus Side-on Coordination of NO to copper(I). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 1205–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Wasbotten IH; Ghosh A Modeling Side-on NO Coordination to Type 2 Copper in Nitrite Reductase: Structures, Energetics, and Bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 15384–15385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ghosh S; Dey A; Usov OM; Sun Y; Grigoryants VM; Scholes CP; Solomon EI Resolution of the Spectroscopy versus Crystallography Issue for NO Intermediates of Nitrite Reductase from Rhodobacter Sphaeroides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 10310–10311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Merkle AC; Lehnert N The Side-on Copper(I) Nitrosyl Geometry in Copper Nitrite Reductase Is Due to Steric Interactions with Isoleucine-257. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 11504–11506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Puiu SC; Warren TH Three-Coordinate-Diketiminato Nickel Nitrosyl Complexes from Nickel(I)-Lutidine and Nickel(II) - Alkyl Precursors. Organometallics 2003, 22, 3974–3976. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Kundu S; Stieber SCE; Ferrier MG; Kozimor SA; Bertke JA; Warren TH Redox Non-Innocence of Nitrosobenzene at Nickel. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 10321–10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).(a) Hayton TW; Legzdins P; Sharp WB Coordination and Organometallic Chemistry of Metal-NO Complexes. Chem. Rev 2002, 102, 935–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Böhmer J; Haselhorst G; Wieghardt K; Nuber B The First Mononuclear Nitrosyl(oxo)molybdenum Complex: Side-On Bonded and μ3-bridging NO Ligands in [{MoL(NO)(O)-(OH)}2NaPF6·H2O. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1994, 33, 14731476. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Neese F Orca: an ab initio, DFT and Semiempirical Electronic Structure Package, Version 3.0.3; Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion: Mulheim an der Ruhr, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- (27).(a) Tomson NC; Crimmin MR; Petrenko T; Rosebrugh LE; Sproules S; Boyd WC; Bergman RG; Debeer S; Toste FD; Wieghardt K A Step Beyond the Feltham-Enenark Notation: Spectroscopic and Correlated ab Initio Computational Support for an Antiferromagnetically Coupled M(II)-(NO)− Description of Tp*M-(NO)(M = Co, Ni). J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011, 133, 18785–18801.” [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Soma S; Van Stappen C; Kiss M; Szilagyi RK; Lehnert M; Fujisawa K Distorted tetrahedral nickel-nitrosyl complexes: spectroscopic characterization and electronic structure. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2016, 21, 757–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yao S; Bill E; Milsmann C; Wieghardt K; Driess MA “Side-on” superoxonickel Complex [LNi(O2)] with a Square-Planar Tetracoordinate Nickel(II) Center and Its Conversion into [LNi(μ-OH)2NiL]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 7110–7113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Ferretti E; Dechert S; Demeshko S; Holthausen MC; Meyer F Reductive Nitric Oxide Coupling at a Dinickel Core: Isolation of a Key cis-Hyponitrite Intermediate en route to N2O Formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, DOI: 10.1002/anie.201811925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.