Abstract

Background:

Opioid-related overdose rates continue to climb. However, little research has examined the reach of overdose education and naloxone trainings among people who inject drugs (PWID). Understanding gaps in coverage is essential to improving the public health response to the ongoing crisis.

Methods:

We surveyed 298 PWID in Baltimore City, MD. We conducted a latent class analysis of drug use indicators and tested for differences by class in past month overdose, having received overdose training, and currently having naloxone.

Results:

Three classes emerged: cocaine/heroin injection (40.2%), heroin only injection (32.2%), and multi-drug/multi-route use (27.6%). The prevalence of past month overdose differed marginally by class (p=0.06), with the multi-drug/multi-route use class having the highest prevalence (22.5%) and the heroin only class having the lowest (4.6%). The prevalence of previous overdose training differed significantly by class (p=0.02), with the heroin/cocaine class (76.5%) having more training than the other two classes. Training was least common amongst the multi-drug/multi-route class (60.3%), though not statistically different from the heroin only class (63.0%). Classes did not differ significantly in current naloxone possession, although the multidrug/multi-route class exhibited the lowest prevalence of naloxone possession (37.2%).

Conclusions:

People who inject multiple substances are at high risk for overdose and are also the least likely to receive overdose trainings. The current service landscape does not adequately reach individuals with high levels of structural vulnerability and high levels of drug use and homelessness. Actively including this subgroup into harm reduction efforts are essential for preventing overdose fatalities.

Keywords: Polysubstance Use, Overdose, Naloxone, Latent Class Analysis

1. Introduction

Overdose rates have risen dramatically in the United States. More than 72,000 individuals died of an overdose in the US in 2017, representing a 3.1-fold increase in overdose fatalities since 2002 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018). Approximately 49,000 of the 2017 overdose deaths involved opioids, a four-fold increase since 2002 (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018). Opioid related overdose fatalities have skyrocketed in recent years, largely due to the introduction of fentanyl to the drug supply (O’Donnell et al., 2017). More than 20,000 of the 49,000 opioid deaths in 2017 were fentanyl involved (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018).

Beyond fatal overdoses, there were an additional 142,557 non-fatal opioid-involved overdoses identified in emergency departments between July 2016 and September 2017 (Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2018). This statistic underestimates the actual burden of non-fatal overdoses in the US, as many people who use drugs do not call emergency services during an overdose or refuse transport to a hospital after being revived by emergency services (Levine et al., 2016). Non-fatal overdose is a key risk factor for fatal overdose (Caudarella et al., 2016). Given the extent of this burden, overdose is a public health emergency that needs to be ameliorated through scaled up prevention and harm reduction efforts. A nuanced understanding of overdose contributors and gaps in service delivery is essential for tailoring and targeting interventions and maximizing their impact.

A number of drugs have been implicated with risks of both fatal and non-fatal opioid overdoses. Correlates of overdose include concomitant use of cocaine, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol with opioid use (Coffin et al., 2003; Darke et al., 2005). In fact, the risk of overdose when opioids and central nervous system depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines) are combined contributes substantially to the global burden of drug related morbidity (Degenhardt and Hall, 2012). This literature begins to suggest that understanding opioid use within an individual’s substance use profile can improve our ability to identify individuals at high risk for overdose. Latent class analysis (LCA) is a powerful tool to identify polysubstance use profiles. LCA allows researchers to identify subgroups of individuals with similar substance use profiles. To date, multiple LCAs in US based samples have focused on college students and the general adult population (Agrawal et al., 2007; Brooks et al., 2017; Evans-Polce et al., 2016; Haardörfer et al., 2016). However, few studies have explicitly studied profiles of polysubstance use among people who inject drugs (PWID) or other high-risk groups in the context of the ongoing opioid epidemic in the US.

In response to the growing opioid overdose epidemic, overdose education and naloxone distribution trainings have been scaled up in many settings for over 20 years (McDonald et al., 2017). The new fentanyl era has introduced additional challenges for take home naloxone implementation. As higher doses and repeated administrations of naloxone are needed to reverse late presenting fentanyl-involved overdoses, it is more urgent than ever to get take home naloxone into the hands of those who use any drugs that may be contaminated with fentanyl (Fairbairn et al., 2017). Many efforts have focused on training health care providers and first responders (e.g., emergency medical services providers and law enforcement officers) to administer naloxone (Davis et al., 2014a; Davis et al., 2014b; Rando et al., 2015). While these trainings of first responders can make a life-saving difference in some situations, people experiencing or witnessing an overdose do not always call 911 due to lingering fears of police based on previous experiences (Baca and Grant, 2007; Latimore and Bergstein, 2017; Pollini et al., 2006). Policing policies in response to the rise in overdoses have exacerbated these fears and contradict the spirit of laws protecting those who call for help during an overdose emergency.

For example, as of 2016, the Baltimore City Police Department’s policy of treating overdose locations as potential crime scenes, where witnesses are questioned, negates the potential benefits of local Good Samaritan laws due to this mandatory police response (Baltimore Police Department, 2016). Similar policies have been enacted in many other jurisdictions as well, jeopardizing the benefits of widespread Good Samaritan laws. Thus, in many locales, trained medical professionals may not ever be notified of and reach individuals experiencing overdoses in order to administer naloxone.

Interventions like overdose trainings can only save lives if they reach the individuals actually present during an overdose emergency. The World Health Organization has specifically recommended expanding access to naloxone and related trainings among lay people likely to witness or experience an overdose, particularly people who use opioids and their peers (World Health Organization, 2014). Some US cities have made substantial efforts to engage PWID directly into overdose reversal trainings (Baltimore City Health Department, 2018; Tobin et al., 2009; Wheeler et al., 2015). These trainings have been tremendously successful in saving lives, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that more than 26,000 overdoses were successfully reversed with naloxone administered by peers between 1996 and 2014 (Wheeler et al., 2015). However, data regarding overdose training and naloxone coverage among PWID population are not widely available. Understanding how well overdose trainings are penetrating communities of PWID is important for identifying gaps in services and underserved subpopulations.

Current Study.

In the present study, we examine how distinct combinations of substance use and routes of administration are associated with non-fatal overdose and with receiving overdose training. Our goal is to understand if individuals who are most at risk for overdose based on their polysubstance use are also the ones receiving overdose response trainings most frequently and are carrying naloxone so that they can respond in an emergency. Identifying these differences can help identify gaps in current public health responses to the overdose epidemic so that we can more effectively protect the lives of PWID.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Recruitment

The data for the current analysis are from a parent study examining a change in syringe distribution practices of the Baltimore City Health Department mobile, van-based Syringe Service Program (SSP) (Hunter et al., 2018; Park et al., 2018; Sherman et al., 2018). Data were collected between April-November 2016. Participants were sampled from all Baltimore SSP sites in proportion to the number of clients that visit each site. Study staff screened potential participants for eligibility after they finished at the SSP. Participants completed an anonymous Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) survey. SSP clients who participated referred their non-client peers to participate as well. Participants had to be 18 years old or older and able to provide consent orally in English. We compensated participants with a $25 gift card. All participants had injected drugs in their lifetime. Our analytic sample size was 298. This study was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Past Month Drug Use.

We included 11 binary variables indicating whether or not a participant used specific drugs via different routes of administration. These variables addressed the following drug/route combinations: marijuana, crack (smoked), heroin (smoked/snorted), heroin (injected), cocaine (smoked/snorted), cocaine (injected), speedball (injected), pain relievers (swallowed), pain relievers (injected), tranquilizers (swallowed), and buprenorphine (swallowed).

2.2.2. Overdose and Naloxone Outcomes.

Participants reported their own overdose history (“When was your last overdose?”). We created a binary variable indicating whether or not a participant had experienced an overdose in the past month. We asked participants if they had ever received any overdose training in their lifetime (yes/no). Participants also indicated whether they currently had any form of naloxone currently on their person or in their home (yes/no).

2.2.3. Demographic Covariates.

Sex (male, female), race (White, Black, Other), age (18-44, 45 and older), education (less than high school, 12th grade or GED, some college or more), and living situation (own home/apartment, other’s home/apartment, homeless) were all reported by participants. We included these variables as covariates to adjust the distal outcome model (described below).

2.3. Analysis

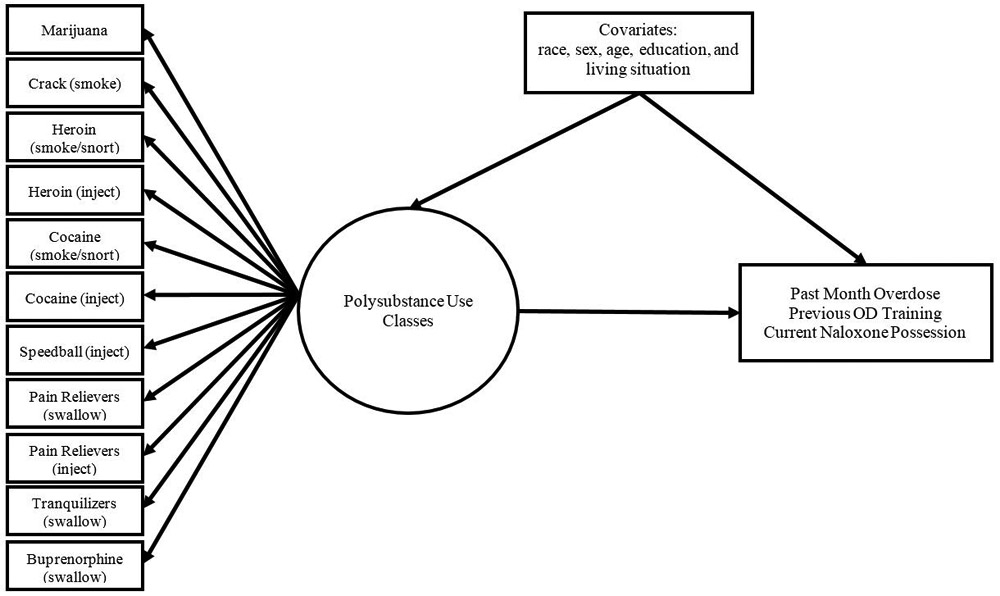

First, we used a latent class analysis (LCA) approach to identify profiles of polysubstance use in our sample using the 11 drug use variables as indicators. LCA is used to identify subgroups of individuals that are homogenous in terms of the LCA indicators, in this case, use of different drugs/routes of administration (Goodman, 1974; Lazarsfeld and Henry, 1968). To do this, we estimated a series of class models with increasing numbers of class (up to 5 classes). We then used the following fit statistics to select the preferred model: log likelihood, Akaike Information Criteria (AIC), Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), model entropy, and Lo- Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Tests (LRT). For the log likelihood and entropy, larger values are favored. For the AIC and BIC, smaller values are preferred. The LRT tests a given model against a model with one fewer classes to determine if the larger model fits significantly better than the smaller model. A significant p-value for the LRT indicates that the smaller model does not fit as well as the larger model, and therefore the larger model is preferred. In addition to considering the fit statistics to choose a model, we also considered the substantive interpretations of the classes in each model to select the final number of classes. To test the associations between latent classes and the outcomes of interest (overdose, overdose training, and current naloxone possession) and to adjust for covariates, we used the Vermunt 3-step approach (Vermunt, 2010). This approach accounts for potential misclassification in the latent classes due to their unobserved nature, in contrast to treating the latent class as an observed variable by formally grouping participants into their most likely class and then testing for differences in outcomes. We adjusted the associations between latent classes and outcomes for sex, race, age, education, and living situation. To compare the prevalence of the overdose and naloxone outcomes between the classes, we used Wald Tests to identify overall differences in outcome between groups. We then followed up the significant Wald Tests with additional “model constraints” to identify any pairwise differences. Figure 1 shows a depiction of this distal outcome analysis modeled. Analyses were conducted using Mplus8 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2017).

Figure 1.

Latent class analysis with distal outcomes model

3. Results

The prevalence of the demographic characteristics, past month drug use indicators, and outcomes are displayed in Table 1. The sample was mostly male (68.8%) and Black (57.7%). Most of the sample (54.7%) was age 45 or older. Only 18.5% had a greater than high school education. Participants’ living situations were relatively evenly distributed between staying in their own home/apartment (37.9%), staying in someone else’s home/apartment (28.5%), and being homeless (33.6%). The prevalence of drug use indicators varied between 9.1% (pain reliever injection) and 89.9% (heroin injection). Fourteen percent of the sample had an overdose in the past month. Most (67.7%) had previously received overdose training, and half (50.9%) currently had naloxone in their possession.

Table 1.

Prevalences of Class Indicators, Outcomes, and Sample Characteristics (N = 298)

| Prevalence (%) | |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 68.8 |

| Female | 31.2 |

| Race | |

| White | 37.3 |

| Black | 57.7 |

| Other | 5.0 |

| Age | |

| 18-44 | 45.4 |

| 45 and older | 54.7 |

| Education | |

| Less than HS | 37.9 |

| 12th grade or GED | 43.6 |

| Some college or more | 18.5 |

| Living Situation | |

| Own house/apartment | 37.9 |

| Other’s house/apartment | 28.5 |

| Homeless | 33.6 |

| Past Month Drug Use | |

| Marijuana | 42.6 |

| Crack (smoked) | 47.3 |

| Heroin (smoked/snorted) | 30.5 |

| Heroin (injected) | 89.9 |

| Cocaine (smoked/snorted) | 13.4 |

| Cocaine (injected) | 47.0 |

| Speedball (injected) | 54.4 |

| Pain Relievers (swallowed) | 24.2 |

| Pain Relievers (injected) | 9.1 |

| Tranquilizers (swallow) | 25.5 |

| Buprenorphine (swallow) | 12.8 |

| Overdose and Training Outcomes | |

| Past Month Overdose | 14.1 |

| Previous Overdose Training | 67.7 |

| Current Naloxone Possession | 50.9 |

3.1. Latent Class Analysis

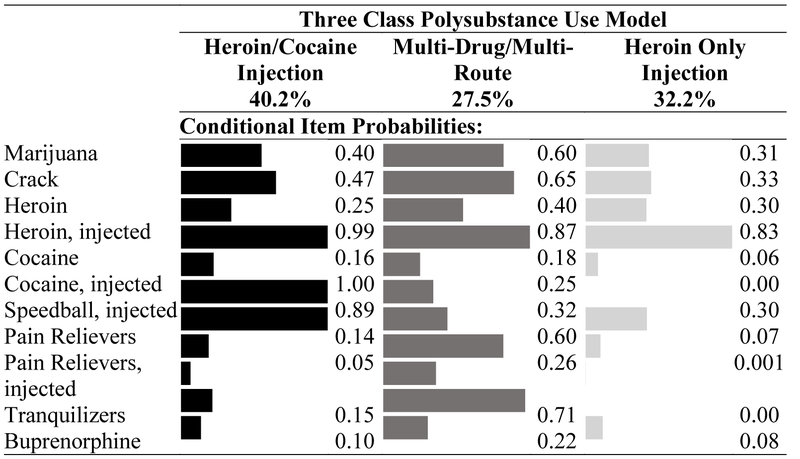

Table 2 summarizes the fit statistics for each model estimated during the class enumeration procedure. Based on these fit statistics, we selected a three-class solution as this model was favored by both the BIC and LRT. The probabilities of the different indicators in each class are displayed in Figure 2. The largest class contained 40.2% of the sample, based on posterior probabilities. This class was characterized by high probabilities of heroin, cocaine, and speedball injection and lower rated of other drug/route of administration indicators. We named this class as the “heroin/cocaine injection” class. The second class was the smallest (27.6% of the sample). This class was characterized by higher probabilities of non-injection drugs than other classes, plus a high probability heroin injection. We named this class the “multi-drug/multi- route” class. The final class made up 32.2% of the sample. This class had a high probability of heroin injection, but low probabilities of other drug use. We named this class the “heroin injection only” class.

Figure 2.

Probabilities of drug use indicators in each class in the three class solution

3.2. Correlates of Latent Class Membership

The prevalence of each correlate by latent class membership are presented in Table 3, where we did observe some variation in sociodemographic characteristics across classes. There were no significant differences in age between classes. The multi-drug/multi-route use class had marginally more females than the heroin/cocaine class ( =0.66, p=0.10). The multi-drug/multi-route use class also had a marginally lower proportion of Black individuals ( =−1.95, p=0.06) and of having a 12th grade or equivalent education ( =−0.99, p=0.07) than the heroin only class. We did not observe any other difference between classes by sex, race, or education. In terms of homelessness, the multi-drug/multi-route use class had the highest prevalence of homelessness (vs heroin only class: =2.09, p<0.01; vs heroin/cocaine class: =0.82, p=0.06). This class also had a marginally higher proportion of individuals staying in someone else’s home than the heroin/cocaine class ( =0.84, p=0.08). Furthermore, the heroin/cocaine class had more homeless individuals than the heroin only class ( =1.27, p=0.003).

Table 2.

Latent Class Model Fit Statistics

| Classes | Smallest Class | Log Likelihood | AIC | BIC | Entropy | LRT p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 47% | −1681.069 | 3408.137 | 3493.170 | 0.767 | 0.0188 |

| 3 | 27.6% | −1641.524 | 3353.048 | 3482.447 | 0.836 | 0.0136 |

| 4 | 13.3% | −1613.568 | 3321.136 | 3494.899 | 0.793 | 0.0946 |

| 5 | 4.1% | −1590.309 | 3298.617 | 3516.746 | 0.850 | 0.1613 |

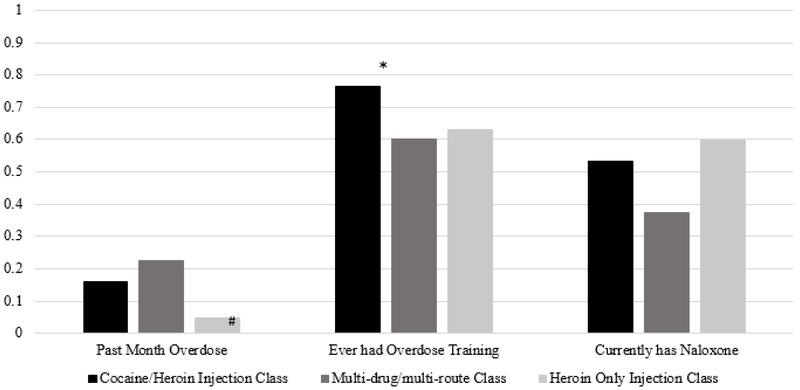

3.3. Overdoses, Overdose Training, and Naloxone Possession by Latent Class

The prevalence of having an overdose in the past month, ever having had an overdose training, and currently possessing naloxone by class are presented in Figure 3. Overdose experiences differed marginally by class (χ=5.72, p=0.06), with the multi-drug/multi-route class having the highest overdose rates (22.5%) and the heroin only class having the lowest (4.6%).

Figure 3.

Proportions of each polysubstance use class with each distal outcome

Note. Overall Wald tests indicated that there were marginal differences between classes for overdose (p=0.06) and significant differences between classes for overdose training (p=0.02). Follow up tests indicated that the cocaine/heroin injection class had significantly higher rates of overdose training than the other classes. # - p<0.1, * - p<0.05

Prevalence of overdose trainings differed significantly by class (χ=7.58, p=0.02). The multi- drug/multi-route class had the lowest trainings rates (60.3%), while the heroin/cocaine injection class had the highest (76.5%). The follow up tests identified that the heroin/cocaine class had higher overdose training rates than the other classes (vs multi-drug/multi-route class: p=0.04; vs heroin only class: p=0.03). The multi-drug/multi-route and heroin only classes did not differ in overdose training (p=0.84). There were no significant differences between classes in terms of current naloxone possession (χ=2.81, p=0.25), but the multi-drug/multi-route class did have lower rates (37.2%) than the other classes (cocaine/heroin: 53.2%; heroin only: 59.7%).

4. Discussion

We identified three distinct classes of substance use among PWID in Baltimore, Maryland that had unique relationships with overdose related outcomes: those who primarily inject heroin only, those who inject both cocaine and heroin, those who inject heroin and use multiple non-injection drugs. The classes we identified are consistent with the findings of previous work that identified profiles of polysubstance use across people who use drugs, regardless of whether or not they inject any drugs (Kuramoto et al., 2011). Overall, 14% of our sample had experienced an overdose in the past month. This estimate is relatively high compared to existing estimates, which suggest approximately 14% of PWID in the US and 17% of PWID globally have had a non-fatal overdose in the past year (Martins et al., 2015; Robinson et al., 2017). However, these estimates were made before the era of fentanyl, which has drastically increased the burden of overdose (Rudd et al., 2016). The classes differed marginally in terms of overdose prevalence (multi-drug/multi-route and heroin/cocaine classes higher than heroin only class) and significantly by overdose training history (heroin/cocaine class higher than multi- drug/multi-route and heroin only classes). Fifty-one percent of our sample overall currently had naloxone in their possession, which is on par with estimates from Seattle, Washington (44% past year possession) and Norwegian cities (62% current possession) (Glick et al., 2017; Madah- Amiri et al., 2018). However, our sample likely overestimates the total prevalence of PWID that have received overdose training and have naloxone, as the Baltimore SSP is a key provider of these programs in the city and our study specifically sampled SSP clients. The prevalence of current naloxone possession did not significantly differ by class, though the prevalence estimates ranged from 37% among the multidrug/multi-route class to 70% among the heroin only class. Our results indicate the need for specific public health efforts to reach the most vulnerable subpopulations among PWID, a population typically regarded as homogenous.

Our results emphasize the importance of considering patterns of polysubstance use when addressing the ongoing overdose crisis from a public health perspective. There is a significant gap between overdose risk and overdose trainings among those with polysubstance use. The multi- drug/multi-route group had the highest prevalence of recent overdose but the lowest rates of training and current naloxone possession. This disparity is significant as those at the highest risk for overdose based on the types of drugs that they use have the least training and resources available to respond to an overdose. Despite extensive overdose training efforts in Baltimore City, individuals with polysubstance use are underserved (Baltimore City Health Department, 2018). This may be due to people with polysubstance use being harder to reach for interventions for a variety of possible reasons, including sociodemographic characteristics, long term involvement with street life, or structural vulnerability. For example, the multi-drug/multi-route use class had a high prevalence of homelessness compared to the other classes. Our study has begun to elucidate the gaps in overdose training coverage, but more research is needed to understand why people who use multiple drugs are less likely to receive these much-needed trainings. The ability of our survey to reach such individuals in itself provides evidence that the most vulnerable PWID can be reached by research and harm reduction programs. Barriers to overdose response trainings include both problems accessing trainings and competing survival interests, especially among the most marginalized PWID. Solutions to the gap in overdose training coverage we identified must address both system and individual level barriers in order to be most effective.

Strategies that actively include hard to reach and vulnerable PWID in harm reduction interventions, like overdose trainings, are needed to close gaps in service coverage. One avenue towards closing this gap is making a particular effort to deliver overdose trainings and increase naloxone access to homeless PWID. In our sample the multi-drug/multi-route use class was more likely to be homeless and also had the least access to harm reduction services. Homeless populations are at higher risk for many outcomes, including overdose and difficulty accessing necessary services (Doran et al., 2018; Kerr et al., 2007; O'Driscoll et al., 2001). In order for overdose trainings to reach the most vulnerable PWID, outreach needs to happen where these individuals congregate, like shelters, homeless encampments, and homeless services.

Additionally, naloxone possession was lower in our sample than the prevalence of having received training, suggesting that individuals who use their naloxone are not always able to easily refill it. This gap was especially obvious in the high risk, multi-drug/multi-route use group. Making naloxone refills more accessible and affordable can help reduce this gap. Overall, additional efforts to reach the most vulnerable PWID with trainings and naloxone access are essential to effectively avert future overdose fatalities.

Furthermore, the public health response to the ongoing overdose crisis can take some important lessons from the response to HIV during the 1980s and 1990s. In particular, the response to overdoses in the United States would benefit from nimble data collection approaches that reach deep into marginalized communities, such as those employed in HIV epidemics among PWID. One such tool which could be adapted is a “rapid assessment” that employed qualitative methods aimed to quickly understand the nature of a drug scene and its associated HIV risks (Fitch et al., 2002; Fitch et al., 2000). By utilizing the important lessons learned in past epidemics, we will be better able to optimize our response and save lives for the duration of the present opioid epidemic.

This study does have limitations. The primary limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size for a latent class analysis with distal outcomes. Due to the sample size, our study may have been under powered to identify differences in the overdose and naloxone possession outcomes. It is also possible that we may have identified additional classes with a larger sample size. However, our results generally align with a previous study on polysubstance use profiles in Baltimore, which lends additional credibility to our results (Kuramoto et al., 2011). Given this, future studies should replicate and extend these findings in larger samples.

Furthermore, cohort studies are needed to establish if the classes we identified remain stable or change over time. Some initial evidence suggests that polysubstance use profiles may be relatively stable over time, but the research on this phenomenon is limited (Baggio et al., 2014). Our study also cannot provide insight into why the gap between overdose risk and overdose trainings exist. We do not have any information as to why certain individuals did not receive trainings or did not have naloxone. Future research will need to address these topics to inform how trainings can be effectively expanded to reach the most at risk individuals. Despite these limitations, our study is an important step forward in identifying gaps in training coverage to prevent fatal overdoses.

Our study also has a number of strengths that make it an important addition to the literature. First, we were able to identify distinct profiles of substance use that have importantly different overdose outcomes. Second, we were able to identify an important mismatch between overdose risk and harm reduction service utilization, which can inform how service delivery can be supplemented in the future to reach the high risk and underserved subgroups. These strengths make the current study an important contribution to the literature and the public health response to the opioid crisis.

5. Conclusions

Among PWID, those who engage in polysubstance use have higher prevalence of non-fatal overdose than peers who only use heroin or combine cocaine and heroin. Those with polysubstance use are also less likely to receive overdose training and to be in possession of naloxone. This mismatch between risk and services represents a significant gap in the public health response to the overdose crisis. This service gap reflected the different levels of structural vulnerability among PWID, a population that is often regarded as homogenous. Going forward, public health practitioners need to find more effective ways to reach underserved, high risk and vulnerable populations for overdose trainings with specific consideration for their stability and particular needs.

Table 3.

Distribution of Sociodemographic Characteristics by Latent Class Membership

| Class 1 – Heroin/Cocaine Injection |

Class 2 – Multi Drug/Multi Route |

Class 3 – Heroin only Injection |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 75.5% | 60.8% | 67.3% |

| Female | 24.5% | 39.2% | 32.7% |

| Race | |||

| White | 33.8% | 49.0% | 31.5% |

| Black | 61.6% | 42.3% | 66.1% |

| Other | 4.6% | 8.7% | 2.4% |

| Age | |||

| 18-44 | 41.9% | 56.2% | 40.3% |

| 45 and older | 58.1% | 43.8% | 59.7% |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS | 34.8% | 38.2% | 41.6% |

| 12th grade or GED | 48.4% | 35.4% | 44.7% |

| Some college or more | 16.8% | 26.4% | 13.7% |

| Living Situation | |||

| Own house/apartment | 39.2% | 22.5% | 49.6% |

| Other’s house/apartment | 22.8% | 28.3% | 35.8% |

| Homeless | 38.0% | 49.2% | 14.6% |

Highlights.

People who use multiple drugs have more overdoses than those who only use heroin.

Those with polysubstance use receive less overdose training and naloxone.

Homelessness was the strongest correlate of polysubstance use profile in our study.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the Baltimore City Health Department, Needle Exchange Program staff, and study participants.

Footnotes

Role of Funding Source

None.

Conflicts of Interest

None conflict declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, 2007. A latent class analysis of illicit drug abuse/dependence: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction 102, 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca CT, Grant KJ, 2007. What heroin users tell us about overdose. J. Addict. Dis. 26, 63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggio S, Studer J, Deline S, N’Goran A, Dupuis M, Henchoz Y, Mohler-Kuo M, Daeppen JB, Gmel G, 2014. Patterns and transitions in substance use among young Swiss men: A latent transition analysis approach. J. Drug Issues 44, 381–393. [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore City Health Department, 2018. Baltimore City overdose prevention and response information. Available from https://health.baltimorecity.gov/opioid-overdose/baltimore-city-overdose-prevention-and-response-information. Accessed on November 16, 2018.

- Baltimore Police Department, 2016. Overdose response and investigation protocol. Available from https://www.baltimorepolice.org/801-overdose-response-and-investigation-protocol. Accessed on November 16, 2018.

- Brooks B, McBee M, Pack R, Alamian A, 2017. The effects of rurality on substance use disorder diagnosis: a multiple-groups latent class analysis. Addict. Behav. 68, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudarella A, Dong H, Milloy M, Kerr T, Wood E, Hayashi K, 2016. Non-fatal overdose as a risk factor for subsequent fatal overdose among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 162, 51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Galea S, Ahem J, Leon AC, Vlahov D, Tardiff K, 2003. Opiates, cocaine and alcohol combinations in accidental drug overdose deaths in New York City, 1990–98. Addiction 98, 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Williamson A, Ross J, Teesson M, 2005. Non-fatal heroin overdose, treatment exposure and client characteristics: findings from the Australian treatment outcome study (ATOS). Drug Alcohol Rev. 24, 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Ruiz S, Glynn P, Picariello G, Walley AY, 2014. Expanded access to naloxone among firefighters, police officers, and emergency medical technicians in Massachusetts. Am. J. Public Health 104, e7–e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis CS, Southwell JK, Niehaus VR, Walley AY, Dailey MW, 2014. Emergency medical services naloxone access: a national systematic legal review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 21, 1173–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, 2012. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet 379, 55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran KM, Rahai N, McCormack RP, Milian J, Shelley D, Rotrosen J, Gelberg L, 2018. Substance use and homelessness among emergency department patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 188, 328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Polce R, Lanza S, Maggs J, 2016. Heterogeneity of alcohol, tobacco, and other substance use behaviors in US college students: A latent class analysis. Addict. Behav. 53, 80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn N, Coffin PO, Walley AY, 2017. Naloxone for heroin, prescription opioid, and illicitly made fentanyl overdoses: challenges and innovations responding to a dynamic epidemic. Int. J. Drug Policy 46, 172–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch C, Rhodes T, Hope V, Stimson G, Renton A, 2002. The role of rapid assessment methods in drug use epidemiology. Bull. Narc. 54, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch C, Rhodes T, Stimson GV, 2000. Origins of an epidemic: the methodological and political emergence of rapid assessment. Int. J. Drug Policy 11, 63–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SN, Tsui J, Hanrahan M, Banta-Green CJ, Thiede H, 2017. Naloxone uptake and use among people who inject drugs in the Seattle area, 2009–2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 171, e72. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, 1974. Exploratory latent structure analysis using both identifiable and unidentifiable models. Biometrika 61, 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Haardörfer R, Berg CJ, Lewis M, Payne J, Pillai D, McDonald B, Windle M, 2016. Polytobacco, marijuana, and alcohol use patterns in college students: A latent class analysis. Addict. Behav. 59, 58–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter K, Park JN, Allen ST, Chaulk P, Frost T, Weir BW, Sherman SG, 2018. Safe and unsafe spaces: Non-fatal overdose, arrest, and receptive syringe sharing among people who inject drugs in public and semi-public spaces in Baltimore City. Int. J. Drug Policy 57, 25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Fairbairn N, Tyndall M, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E, 2007. Predictors of non-fatal overdose among a cohort of polysubstance-using injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 87, 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto S, Bohnert A, Latkin C, 2011. Understanding subtypes of inner-city drug users with a latent class approach. Drug Alcohol Depend. 118, 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latimore AD, Bergstein RS, 2017. “Caught with a body” yet protected by law? Calling 911 for opioid overdose in the context of the Good Samaritan Law. Int. J. Drug Policy 50, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarsfeld P, Henry N, 1968. Latent structure analysis Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- Levine M, Sanko S, Eckstein M, 2016. Assessing the risk of prehospital administration of naloxone with subsequent refusal of care. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 20, 566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madah- Amiri D, Gjersing L, Clausen T, 2019. Naloxone distribution and possession following a large- scale naloxone programme. Addiction 114, 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Sampson L, Cerdá M, Galea S, 2015. Worldwide prevalence and trends in unintentional drug overdose: a systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Public Health 105, e29–e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald R, Campbell ND, Strang J, 2017. Twenty years of take-home naloxone for the prevention of overdose deaths from heroin and other opioids—Conception and maturation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 178, 176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2017. Mplus User’s Guide. Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018. Overdose death rates. Available from https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Accessed on November 16, 2018.

- O'Driscoll PT, McGough J, Hagan H, Thiede H, Critchlow C, Alexander ER, 2001. Predictors of accidental fatal drug overdose among a cohort of injection drug users. Am. J. Public Health 91, 984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, Seth P, 2017. Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by census region— United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 66, 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Weir BW, Allen ST, Chaulk P, Sherman SG, 2018. Fentanyl-contaminated drugs and non-fatal overdose among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, MD. Harm. Reduct. J. 15, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollini RA, McCall L, Mehta SH, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Strathdee SA, 2006. Response to overdose among injection drug users. Am. J. Prev. Med. 31, 261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando J, Broering D, Olson JE, Marco C, Evans SB, 2015. Intranasal naloxone administration by police first responders is associated with decreased opioid overdose deaths. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 33, 1201–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WT, Kazbour C, Nassau T, Fisher K, Sheu S, Rivera AV, Al-Tayyib A, Glick SN, Braunstein S, Barak N, 2017. Brief report: nonfatal overdose events among persons who inject drugs findings from seven national HIV behavioral surveillance cities 2009 and 2012. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 75, S341–S345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd R, Seth P, David F, Scholl L, 2016. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 65, 1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Schneider KE, Park JN, Allen ST, Hunt D, Chaulk CP, Weir BW, 2018. PrEP awareness, eligibility, and interest among people who inject drugs in Baltimore, Maryland. Drug Alcohol Depend. 195, 148–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin KE, Sherman SG, Beilenson P, Welsh C, Latkin CA, 2009. Evaluation of the Staying Alive programme: training injection drug users to properly administer naloxone and save lives. Int. J. Drug Policy 20, 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, 2010. Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Polit. Anal. 18, 450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Vivolo-Kantor AM, Seth P, Gladden RM, Mattson CL, Baldwin GT, Kite-Powell A, Coletta MA, 2018. Vital signs: trends in emergency department visits for suspected opioid overdoses—United States, July 2016–September 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 67, 279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ, 2015. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons-United States, 2014. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 64, 631–635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2014. Community management of opioid overdose. Available from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/management_opioid_overdose/en/. Accessed on November 16, 2018. [PubMed]