INTRODUCTION

The intervertebral disc (IVD) is an avascular structure comprised of an aggrecan-rich nucleus pulposus (NP) surrounded by concentric layers of collagen forming the annulus fibrosus (AF). The pathophysiology of IVD degeneration involves disorganization of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and loss of proteoglycan content leading to dehydration of the NP. This leads to microfissure formation, which coalesce into tears extending to the AF. Annular tears can result in herniation of NP contents and compression of neighboring neurologic structures.1 Lumbar discectomy is performed in 300,000 individuals annually, and while predominantly successful in relieving acute symptoms, the procedure does not address the progressive disc degeneration that ensues.2 Furthermore, the annular defect is not treated and exacerbated during surgery. Persistent annular defects increase the risk of recurrent disc herniation, which requires reoperation in 6–13% of cases.3–8

Several attempts have been made to mechanically repair AF defects using suture and annuloplasty devices. However, none of these techniques significantly alter annular healing in animal models nor demonstrate long-term benefits in recent clinical trials.9–12 To this end, biological approaches for annular repair and prevention of progressive DDD have become of increasing interest.13–17 Iatridis et al. engineered an injectable fibrin-genipin adhesive hydrogel sealant which prevented IVD height loss and remained well-integrated with native AF tissue following extended compression cycles in vitro, as well fully restoring compressive stiffness in vivo.18 Mesenchymal progenitor cells combined with pentosan polysulfate embedded in a gelatin/fibrin scaffold restored IVD height, morphology, and NP proteoglycan content in ovine models six months after simulated discectomy.19

We have previously reported the development of a riboflavin (RF) cross-linked high-density collagen (HDC) gel for the treatment of annular injuries.20–22 Collagen prepared with RF has the advantage of maintaining a low, injectable viscosity until exposed to blue light, which photo-initiates cross-linking of collagen fibrils to form a hydrogel with increased mechanical properties. Using an in vivo rat-tail model, HDC gel helped retain 70–80% of NP tissue 18 weeks post-injury.22 In contrast, negative control IVDs showed complete NP extrusion and terminal degenerative changes by 5 weeks.22

Although these results were promising, rat-tail spine outcomes have limited clinical translation. Ovine lumbar spines have comparable anatomical, cellular, and biomechanical features to humans, and are frequently used as translational in vivo models for spine disease.23–25 Like humans, sheep are among the few mammals that rapidly lose notochordal cells in the IVD following birth. Persistence of these cells, as seen in rats, rabbits, and pigs, can influence proteoglycan metabolism and progenitor cell differentiation.26–28 Physiological loading properties are similar to human IVDs and experience comparable mechanical alterations after annular injury.29–32 As such, annular injury in sheep models induces histological and radiographical degenerative changes similar to those seen in humans.30,31.

The objectives of the present study were as follows. First, to validate a modification of a previously described drill-bit injury technique to induce IVD degeneration in an ovine model.33 Second, to perform a lateral access, extraperitoneal approach to the sheep lumbar spine to deliver an injectable HDC gel after induced AF injury. Third, to assess the histological and radiographical changes in injured sheep IVDs treated with the HDC gel as compared with negative controls over a 16-week period.

MATIERIALS AND METHODS

Study Groups

This study was approved by the Cornell University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eight skeletally mature sheep aged 4–7 years old were obtained through the Cornell University Ruminant Center. A total of 40 disc segments from L1/2 to L5/6 were randomized into one of three groups. The first group included healthy discs that were not manipulated (healthy control) (N=10), the second group contained injured IVDs treated with HDC gel (N=15), and the third group consisted of injured IVDs with no treatment (negative control) (N=15). Randomization across all levels was implemented to mitigate focal segmental variance. All sheep were euthanized at 16 weeks following standard protocol from the American Veterinary Medical Association.

High-Density Collagen Gel Preparation

Collagen was harvested and reconstituted from rat-tail tendon as previously described34,35 (see Supplemental Digital Content 1 for detailed methodology).

Annular Drill Injury Surgical Technique

All surgical procedures were performed in accordance with the Weill Cornell Medical College Research Animal Resource Center guidelines. A technique modified from Oehme et al. was utilized36 (see Figure 1 and Supplemental Digital Content 1 for detailed surgical approach).

Figure 1:

Intraoperative photographs of the lateral approach to the sheep lumbar spine disc space. A) Right lateral positioning of the sheep. A longitudinal incision is marked from the 12th rib to the iliac crest, approximately 1cm inferior the palpable transverse processes. B) 3.2mm drill-bit injury to the IVD; B) Annular defect in the IVD after drill-bit injury; C) Injection of 1cc of 0.5mM RF cross-linked HDC gel using a syringe with stopcock; E) A blue light with a 480nm wavelength is applied for 40 seconds after injection of the HDC to initiate riboflavin cross-linking. F) Annular defect with HDC gel plug.

Histology

All disc segments were fixed with 10% neutralized formalin supplemented with 1% cetylpyridinium chloride, then decalcified using 5% nitric acid for 1–2 months. They were then cut in the mid-coronal plane along the trajectory of the drilled annular defect, and transferred to 75% ethanol. Segments were embedded in paraffin, cut to 5-μm thickness, and stained with Picrosirius Red and Safranin-O.

MRI Analysis

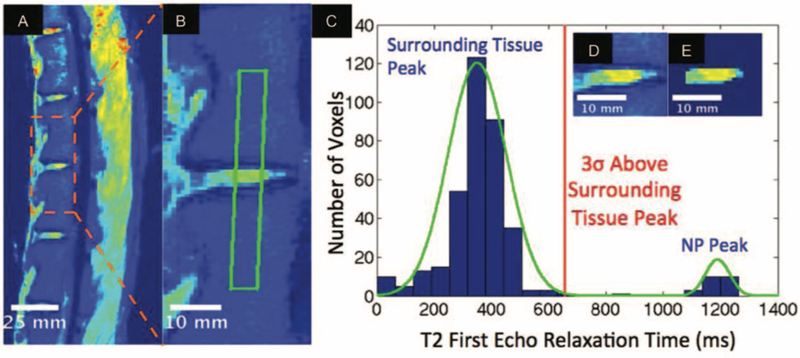

3T MRI (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) was performed on all lumbar spines at 16 weeks. For qualitative analysis, two blinded observers used a modified Pfirrmann scale to classify discs between eight grades of degeneration taking NP size, degree of hyperintensity, clarity of the AF/NP border, and disc height into account 37,38. For quantitative analysis, a previously described method developed by our group was modified for the ovine spine to quantify NP mid-sectional volume and average T2-relaxation time (T2-RT).39 This algorithm filters out all MRI voxels not representing NP tissue according to their respective T2-RT. Briefly, the algorithm applies a Gaussian mixture model to a rectangle of voxels spanning two adjacent vertebrae from the first-echo T2 image (Figure 2A–B) to separate intensities into two distinct populations of either NP or surrounding bone and soft tissue. NP is segmented from surrounding tissues by thresholding voxels at three standard deviations higher than the average surrounding tissue relaxation time (Figure 2C–E). The NP mask segmented from the first-echo image is then applied to the T2 mapped image to calculate NP average T2-RT and mid-sectional volume (Figure 3). The mean T2-RT and mid-sectional volume of experimental segments were compared with proximal adjacent healthy discs.

Figure 2: Quantitative MRI analysis of sheep IVD.

A) Representative mid-sagittal first-echo T2 MRI of a sheep spine; B) Magnified T2 MRI of the IVD to show the outlined area spanning NP and the adjacent vertebrae where voxels are collected for the Gaussian mixture model (GMM); C) Histogram of voxel relaxation time fit to a two population GMM, with the red line showing three standard deviations greater than the surrounding tissue peak as a threshold for NP segmentation; D) Before and E) after algorithmic NP segmentation.

Figure 3:

Representative T2 mapped image of an ex vivo sheep spine showing the algorithmically segmented NP of untreated, treated, and adjacent healthy IVDs.

Disc Height Measurements

XRs were performed in all sheep at 16 weeks for disc height analysis. Care was taken to achieve true lateral radiographs of the segment. The IVD height was measured using a modified method previously described by Lu et al., which determines disc height index (DHI) by dividing the disc height by the adjacent vertebral body height.40

Statistics

All quantitative values from XRs and MRIs represent the proportion of experimental to adjacent healthy control measurements, and were expressed as mean ± SD. A two-way ANOVA was used to analyze statistical differences between treatment groups and disc levels, and comparisons between treatment groups were made with one-way student’s t-tests. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Histology

Picrosirius Red stain for collagen was used to delineate the structure of the AF. Healthy IVDs demonstrated a clear AF/NP interface and vertically organized lamellar layers that were symmetric to the contralateral side. Injured IVDs treated with HDC gel had only mild reduction in NP area on representative coronal cuts compared with healthy controls as well as early reorganization of lamellar layers on the side of injury. Staining intensity extended into a fibrous cap overlying the defect, which approximated the underlying AF structure. The contralateral AF maintained vertical lamellar organization. In contrast, negative controls demonstrated severe disorganization of lamellar structure on the side of injury and over 50% reduction in NP area on representative coronal cuts. There was infolding of the contralateral AF with further reduction in NP dimensions. Decreased staining intensity and disorganization of the subjacent cartilaginous layers were noted, along with new border irregularities signifying early endplate destruction (Figure 4A–C).

Figure 4: Representative Coronal Histological Sections of Ovine IVDs.

A-C) Picrosirius red staining for collagen. A) Healthy IVD; B) 16-week post–injury IVD treated with HDC gel. Note the moderately preserved lamellar structure of collagen fibers of the AF and organized extension into the fibrous cap (asterix); C) 16-week post–injury IVD with no treatment. There is complete disorganization of the AF (asterix) and infolding of the contralateral AF due to loss of disc height and NP volume (white triangle). Decreased staining intensity in the endplate suggests early destruction. D-F) Safranin-O staining for NP proteoglycan. D) Healthy IVD. E) 16-week post–injury disc segment treated with HDC collagen. In C note some mild loss of NP structure (asterix), and in D the formation of a fibrous collagen cap. F) 16-week post–injury disc segment with no treatment. In E, note endplate changes (black triangles) as well loss of proteoglycan structure and scar tissue formation in the region of the defect (black arrow). In F, note the lack of a fibrous collagen cap and extension of scar tissue laterally outside the border of the lateral disc complex (black arrow). Also note vacuolization of the NP (circled) caused by herniation through the defect.

In healthy discs, Safranin-O the AF/NP border was clearly defined, with evenly diminishing transitions into the deep layers of the AF. In treated IVDs, mild reduction in NP height with small regions of breakdown of the ipsilateral border was observed. Again noted was a fibrous cap which was clearly demarcated from the underlying AF and displayed moderately organized structure. There was less NP vacuolization and endplate destruction compared to untreated IVDs. In contrast, untreated IVDs demonstrated marked loss of NP height and islets of vacuolization within the disc signifying advanced stages of degeneration. A substantial loss of the ipsilateral AF border was observed, which signified persistent rupture and connective scar tissue along the tract of injury extending into the disc (Fig. 4D–F).

Qualitative MRI Assessment

All uninjured segments demonstrated a Pfirrmann grade of 1, whereas injured segments demonstrated varying degrees of degeneration. IVDs treated with HDC gel demonstrated Pfirrmann grades ranging from 2 to 3, with a mean of 2.5 (± 0.5). Negative control IVDs had Pfirrmann grades ranging from 2 to 4, with a mean of 2.6 (± 0.7) (Figure 6). There was no statistically significant difference between these two groups (P=0.78).

Figure 6:

Algorithmically quantified A) average NP T2-RT and B) NP mid-sectional volume for adjacent healthy, treated, and untreated IVDs. Bars denote statistically significant differences between treatment groups. Error bars are + standard deviation.

Quantitative MRI Analysis

The average T2-RT was calculated from the mid-sagittal cut of the T2 map and was quantified from the segmented NPs. This yielded average T2-RT of 52.9±17.8ms, 38.1±5.4ms, and 35.4±3.6ms for healthy, treated, and untreated IVDs, respectively (Figure 6). The difference between treated/untreated IVDs approached but did not reach statistical significance (P=0.054).

The size of the NP was assessed using the voxel count within a mid-sagittal cut of the T2 first-echo image. The average NP voxel count was found to be 71.3±14.9, 69.3±24.4, and 71.5±21.7 voxels for healthy, treated, and untreated IVDs, respectively (Figure 6). There was no statistically significant difference between healthy and injury groups or between injury groups with and without treatment (P=0.395 and P=0.424, respectively).

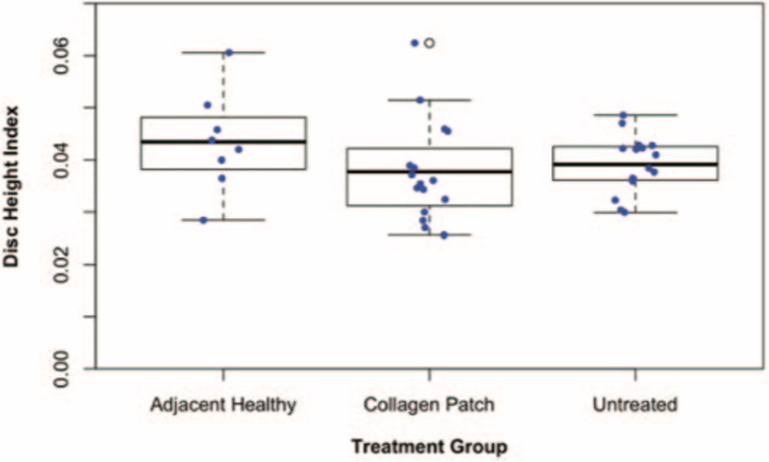

Disc Height Measurements

The mean DHI was 0.043±0.001, 0.037±0.001, and 0.039±0.005 for healthy, treated, and untreated IVDs, respectively (Figure 7). There was no statistically significant difference between treated and untreated discs (P=0.6156).

Figure 7:

Disc Height Indices (DHI) for adjacent healthy, treated, and untreated IVDs. Error bars are + standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first in vivo assessment of a RF cross-linked HDC gel in a large animal model of induced IVD degeneration to date. We safely performed lateral approach surgeries to the ovine lumbar spine in a reproducible manner without short- or long-term complications. Based on histological findings, HDC gel application prevented features of severe degeneration at 16 weeks. Radiographic findings suggested that application of HDC gel slightly improved NP hydration, but no statistically significant differences between treated and untreated IVDs were observed.

Safe and reproducible surgical approach to the ovine lumbar spine

We were able to successfully perform and standardize the lateral, extraperitoneal approach to the ovine lumbar spine. None of the 8 sheep experienced intraoperative complications such as excessive blood loss (>500mL), durotomy, vertebral body fractures, or spinal cord injury. The HDC gel was easy to deliver with minimal dissection, exposure, and added time. There were no instances of postoperative neurologic deficits, wound complications, adverse immune response, or infections. All collagen patches stayed in place through the 16 weeks of the study.

Histological and imaging analysis

Histological examination of between treated and untreated IVDs revealed marked differences. The formation of a fibrous cap resulted in decreased AF and NP disorganization, analogous to the rat-tail model.22 Hallmarks of DDD including loss of disc height and endplate destruction were more prominent in the untreated group. Staining intensity of proteoglycan content in treated IVDs approached that of healthy IVDs compared to minimal intensity on the injured side in the untreated group. Increased vacuolization and persistent scar tissue along the tract of the drill-bit demonstrated more advanced stages of degeneration in the untreated group.

In patients with corneal ectasia due to connective tissue disorder for example, application of RF cross-linked collagen increased biomechanical strength and reduced permeability to water.41 Concordantly, the fibrous cap formed by the HDC gel observed at the annular injury site served not only as a mechanical buttress to prevent herniation of NP contents, but possibly also prevented the diffusion of water molecules bound to proteoglycans from the NP. This reduction in dehydration allowed the NP to maintain volume compared to untreated IVDs. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the RF cross-linked HDC gel prevents the rate at which degeneration occurs in injured IVDs at the microscopic level.

Imaging studies did not reveal statistically significant differences, but showed that none of the treated IVDs achieved Pfirrmann grade 4, which was the most severe stage of degeneration observed. Likewise, the mean T2-RT suggested slightly increased retention of NP hydration in the treated segments. No differences were noted between each of the tested groups in regards to NP voxel size or DHI.

Discrepancy between histological and radiographic outcomes

There are a number of possibilities to explain the marked differences observed in at the histological and radiographic levels. First, an extended period of time may be required for the repaired AF to have reached the point where it would not allow further degeneration of the NP. Second, the stable NP voxel size and DHI observed between healthy and injury groups suggests that the drill-bit injury technique leads to changes that are apparent on histology, but not substantial enough to translate into imaging endpoints. Due to less disruption of the AF and NP milieu, induction of degenerative changes required to induce loss of disc height or decrease in NP volume was not met, thus the ability to assess the efficacy of the HDC gel was diminished. Third, aging sheep are known to develop calcified deposits in the transitional zone between the AF and NP, leading to progressively denser IVDs.28 Our sheep were aged 4–7 years old (average life span is 10–12 years), these microcalcifications may have restricted the ability of the injury technique to inflict significant damage beyond the tract of injury. This is in contrast to rat-tail IVDs, which have a liquid consistency that allows the rapid extrusion of NP following injury.42 Fourth, while MRI is the gold standard for assessing NP hydration and structure, its ability to delineate the fine anatomical organization of the AF are unclear. Notably, clear structural differences that were noted in collagen organization as demonstrated by polarized light microscopy were not manifested in MRI analysis. As mentioned above, there is an undetermined lag time between NP reorganization and annular repair, therefore focusing imaging endpoints around the NP at too early of a time point may be misleading. The use of 7T MRI may circumvent these obstacles by providing more advanced spatial resolution which correlates more accurately with cellular features.43,44 However, 7T MRIs are limited by economic and logistical constraints in the research arena at this time.

Other groups have described similar discordant results between histological and radiographic studies in animal models. Rabbits demonstrate decreased gene expression of NP collagen and dramatic microscopic changes related to loss of proteoglycan content with normal aging despite relatively modest age-related MRI changes.45 Nonchondrodystrophoid dogs display histological evidence of degeneration that predate radiological and biomechanical changes.46 Goats subjected to drill-bit injury likewise show significant degenerative changes in cell density, morphology, and ECM appearance at 2 months, but no correlative findings on MRI.33 In contrast, partial thickness annular incision techniques for IVD injury in ovine models demonstrated significant changes in imaging concordant with histological loss of morphology and proteoglycan content, within three months of injury.29,47 To what extent the injury technique, age, and time frame for post-mortem assessment factor into the relationship between histological and radiographical parameters in a sheep model remains unclear.

Limitations

There are limitations of our study that should be acknowledged. The small sample size of 40 IVDs may not be powered enough to accurately discern changes between experimental groups. Notably, the lack of statistical difference of the effect of the collagen patch on T2-RT (P=0.0539) is likely the result of type II statistical error. We also did not use a quantitative histological method for characterizing the degree of IVD degeneration due to several sections that were not orthogonal to the drill-bit tract. Finally, biomechanical testing was not performed, therefore the functional implications and ability of the collagen gel to stay in the defect under higher pressures remains undetermined.

CONCLUSION

Injectable HDC gel can be delivered in a safe and reproducible manner using lateral access surgery in the ovine model. HDC gel application mitigated AF disorganization and reduced NP degeneration at the microscopic level. Radiographic changes were slight when comparing treated to untreated IVDs. These results indicate that HDC gel is a potential option for annular repair but requires further analysis in large animal models. Further work is currently being conducted using a more aggressive injury model and longer follow-up period.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5: Qualitative MRI results based on Pfirrmann grade.

Top: Box plot of results for healthy, injured and treated with collagen gel, and injured and untreated disc segments. All controls were Pfirrmann grade 1. Darkened bars denote mean values. Note that only grade 4 degeneration was seen in untreated discs. Bottom: Representative axial MRI cuts through the IVD demonstrating the grade 1–4 observed, with group assignment also noted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Project no. (S-14-123Y) was supported by the AO Foundation.

References

- 1.Freemont A, Watkins A, Le Maitre C, Jeziorska M, Hoyland J. Current understanding of cellular and molecular events in intervertebral disc degeneration: implications for therapy. The Journal of pathology. 2002;196(4):374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas SJ, Deyo RA, Patrick DL, Convery K, Keller RB, Singer DE. The Quebec Task Force classification for Spinal Disorders and the severity, treatment, and outcomes of sciatica and lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(24):2885–2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swartz KR, Trost GR. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(3):E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carragee EJ, Han MY, Suen PW, Kim D. Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(1):102–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrossi GL, McGirt MJ, Sciubba DM, Witham TF, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL, Long DM. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation after single-level lumbar discectomy: incidence and health care cost analysis. Neurosurgery. 2009;65(3):574–578; discussion 578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frymoyer JW, Hanley E, Howe J, Kuhlmann D, Matteri R. Disc excision and spine fusion in the management of lumbar disc disease. A minimum ten-year followup. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laus M, Bertoni F, Bacchini P, Alfonso C, Giunti A. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation: what recurs? (A morphological study of recurrent disc herniation). Chir Organi Mov. 1993;78(3):147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruske-Hohlfeld I, Merritt JL, Onofrio BM, Stonnington HH, Offord KP, Bergstralh EJ, Beard CM, Melton LJ 3rd, Kurland LT. Incidence of lumbar disc surgery. A population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950–1979. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(1):31–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bron JL, Helder MN, Meisel HJ, Van Royen BJ, Smit TH. Repair, regenerative and supportive therapies of the annulus fibrosus: achievements and challenges. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(3):301–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlgren BD, Lui W, Herkowitz HN, Panjabi MM, Guiboux JP. Effect of anular repair on the healing strength of the intervertebral disc: a sheep model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(17):2165–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey A, Araghi A, Blumenthal S, Huffmon GV. Prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled study of anular repair in lumbar discectomy: two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(14):1161–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bron JL, van der Veen AJ, Helder MN, van Royen BJ, Smit TH, Skeletal Tissue Engineering Group A, Research Institute M. Biomechanical and in vivo evaluation of experimental closure devices of the annulus fibrosus designed for a goat nucleus replacement model. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(8):1347–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirvu T, Blanquer SB, Benneker LM, Grijpma DW, Richards RG, Alini M, Eglin D, Grad S, Li Z. A combined biomaterial and cellular approach for annulus fibrosus rupture repair. Biomaterials. 2015;42:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire R, Borem R, Mercuri J. The fabrication and characterization of a multi-laminate, angle-ply collagen patch for annulus fibrosus repair. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xin L, Zhang C, Zhong F, Fan S, Wang W, Wang Z. Minimal invasive annulotomy for induction of disc degeneration and implantation of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) plugs for annular repair in a rabbit model. Eur J Med Res. 2016;21:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long RG, Rotman SG, Hom WW, Assael DJ, Grijpma DW, Iatridis JC. In vitro and biomechanical screening of polyethylene glycol and poly(trimethylene carbonate) block copolymers for annulus fibrosus repair. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Likhitpanichkul M, Kim Y, Torre OM, See E, Kazezian Z, Pandit A, Hecht AC, Iatridis JC. Fibrin-genipin annulus fibrosus sealant as a delivery system for anti-TNFalpha drug. Spine J. 2015;15(9):2045–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Likhitpanichkul M, Dreischarf M, Illien-Junger S, Walter BA, Nukaga T, Long RG, Sakai D, Hecht AC, Iatridis JC. Fibrin-genipin adhesive hydrogel for annulus fibrosus repair: performance evaluation with large animal organ culture, in situ biomechanics, and in vivo degradation tests. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:25–37; discussion 37–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oehme D, Ghosh P, Shimmon S, Wu J, McDonald C, Troupis JM, Goldschlager T, Rosenfeld JV, Jenkin G. Mesenchymal progenitor cells combined with pentosan polysulfate mediating disc regeneration at the time of microdiscectomy: a preliminary study in an ovine model. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(6):657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudson KD, Alimi M, Grunert P, Hartl R, Bonassar LJ. Recent advances in biological therapies for disc degeneration: tissue engineering of the annulus fibrosus, nucleus pulposus and whole intervertebral discs. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(5):872–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borde B, Grunert P, Härtl R, Bonassar LJ. Injectable, high‐density collagen gels for annulus fibrosus repair: An in vitro rat tail model. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2015;103(8):2571–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grunert P, Borde BH, Hudson KD, Macielak MR, Bonassar LJ, Hartl R. Annular repair using high-density collagen gel: a rat-tail in vivo model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(3):198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid JE, Meakin JR, Robins SP, Skakle JM, Hukins DW. Sheep lumbar intervertebral discs as models for human discs. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2002;17(4):312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt H, Reitmaier S. Is the ovine intervertebral disc a small human one? A finite element model study. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2013;17:229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilke H-J, Kettler A, Claes LE. Are Sheep Spines a Valid Biomechanical Model for Human Spines? Spine. 1997;22(20):2365–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aguiar DJ, Johnson SL, Oegema TR. Notochordal cells interact with nucleus pulposus cells: regulation of proteoglycan synthesis. Exp Cell Res. 1999;246(1):129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daly C, Ghosh P, Jenkin G, Oehme D, Goldschlager T. A Review of Animal Models of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Pathophysiology, Regeneration, and Translation to the Clinic. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:5952165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alini M, Eisenstein SM, Ito K, Little C, Kettler AA, Masuda K, Melrose J, Ralphs J, Stokes I, Wilke HJ. Are animal models useful for studying human disc disorders/degeneration? Eur Spine J. 2008;17(1):2–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melrose J, Shu C, Young C, Ho R, Smith MM, Young AA, Smith SS, Gooden B, Dart A, Podadera J, Appleyard RC, Little CB. Mechanical destabilization induced by controlled annular incision of the intervertebral disc dysregulates metalloproteinase expression and induces disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(1):18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melrose J, Ghosh P, Taylor TK, Hall A, Osti OL, Vernon-Roberts B, Fraser RD. A longitudinal study of the matrix changes induced in the intervertebral disc by surgical damage to the annulus fibrosus. J Orthop Res. 1992;10(5):665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melrose J, Ghosh P, Taylor TK, Latham J, Moore R. Topographical variation in the catabolism of aggrecan in an ovine annular lesion model of experimental disc degeneration. J Spinal Disord. 1997;10(1):55–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore RJ, Vernon-Roberts B, Osti OL, Fraser RD. Remodeling of vertebral bone after outer anular injury in sheep. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(8):936–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Drapeau S, An HS, Markova D, Lenart BA, Anderson DG. Histological features of the degenerating intervertebral disc in a goat disc-injury model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(19):1519–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cross VL, Zheng Y, Won Choi N, Verbridge SS, Sutermaster BA, Bonassar LJ, Fischbach C, Stroock AD. Dense type I collagen matrices that support cellular remodeling and microfabrication for studies of tumor angiogenesis and vasculogenesis in vitro. Biomaterials. 2010;31(33):8596–8607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowles RD, Williams RM, Zipfel WR, Bonassar LJ. Self-assembly of aligned tissue-engineered annulus fibrosus and intervertebral disc composite via collagen gel contraction. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(4):1339–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oehme D, Goldschlager T, Rosenfeld J, Danks A, Ghosh P, Gibbon A, Jenkin G. Lateral surgical approach to lumbar intervertebral discs in an ovine model. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:873726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu LP, Qian WW, Yin GY, Ren YX, Hu ZY. MRI assessment of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration with lumbar degenerative disease using the Pfirrmann grading systems. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e48074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griffith JF, Wang Y-XJ, Antonio GE, Choi KC, Yu A, Ahuja AT, Leung PC. Modified Pfirrmann grading system for lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine. 2007;32(24):E708–E712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grunert P, Hudson KD, Macielak MR, Aronowitz E, Borde BH, Alimi M, Njoku I, Ballon D, Tsiouris AJ, Bonassar LJ, Härtl R. Assessment of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration Based on Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analysis: An In Vivo Study. Spine. 2014;39(6):E369–E378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu DS, Shono Y, Oda I, Abumi K, Kaneda K. Effects of chondroitinase ABC and chymopapain on spinal motion segment biomechanics. An in vivo biomechanical, radiologic, and histologic canine study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(16):1828–1834; discussion 1834–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart JM, Lee OT, Wong FF, Schultz DS, Lamy R. Cross-linking with ultraviolet-a and riboflavin reduces corneal permeability. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(12):9275–9278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michalek AJ, Funabashi KL, Iatridis JC. Needle puncture injury of the rat intervertebral disc affects torsional and compressive biomechanics differently. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(12):2110–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bateman AH, Balkovec C, Akens MK, Chan AH, Harrison RD, Oakden W, Yee AJ, McGill SM. Closure of the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc using a novel suture application device-in vivo porcine and ex vivo biomechanical evaluation. Spine J. 2016;16(7):889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon SM, Yoder JH, Wright AC, Smith LJ, Vresilovic EJ, Elliott DM. Evaluation of intervertebral disc cartilaginous endplate structure using magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(8):1820–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sowa G, Vadala G, Studer R, Kompel J, Iucu C, Georgescu H, Gilbertson L, Kang J. Characterization of intervertebral disc aging: longitudinal analysis of a rabbit model by magnetic resonance imaging, histology, and gene expression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(17):1821–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillett NA, Gerlach R, Cassidy JJ, Brown SA. Age-related changes in the beagle spine. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;59(5):503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oehme D GT, Shimon S, et al. Radiological, Morphological, Histological and Biochemical Changes of Lumbar Discs in an Animal Model of Disc Degeneration Suitable for Evaluating the Potential Regenerative Capacity of Novel Biological Agents. J Tissue Sci Eng. 2015;6(2). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.