Abstract

Background

Interventions that enable people to remain in their own home as they age are of interest to stakeholders, yet detailed information on effective interventions is scarce. Our objective was to systematically search and synthesise evidence for the effectiveness of community-based, aged care interventions in delaying or avoiding admission to residential aged care.

Method

Nine databases were searched from January 2000 to February 2018 for English publications. Reference lists of relevant publications were searched. The databases yielded 55,221 citations and 50 citations were gleaned from other sources. Where there was sufficient homogeneity of study design, population, intervention and measures, meta-analyses were performed. Studies were grouped by the type of intervention: complex multifactorial interventions, minimal/single focus interventions, restorative programs, or by the target population (e.g. participants with dementia).

Results

Data from 31 randomised controlled trials (32 articles) that met our inclusion criteria were extracted and analysed. Compared to controls, complex multifactorial interventions in community aged care significantly improved older adults’ ability to remain living at home (risk difference − 0.02; 95% CI -0.03, − 0.00; p = 0.04). Commonalities in the 13 studies with complex interventions were the use of comprehensive assessment, regular reviews, case management, care planning, referrals to additional services, individualised interventions, frequent client contact if required, and liaison with General Practitioners. Complex interventions did not have a significantly different effect on mortality.

Single focus interventions did not show a significant effect in reducing residential aged care admissions (risk difference 0, 95% CI -0.01, 0.01; p = 0.71), nor for mortality or quality of life.

Subgroup analysis of complex interventions for people with dementia showed significant risk reduction for residential aged care admissions (RD -0.05; 95% CI -0.09, -0.01; p = 0.02). Compared to controls, only interventions targeting participants with dementia had a significant effect on improving quality of life (SMD 3.38, 95% CI 3.02, 3.74; p < 0.000001).

Conclusions

Where the goal is to avoid residential aged care admission for people with or without dementia, there is evidence for multifactorial, individualised community programs. The evidence suggests these interventions do not result in greater mortality and hence are safe. Minimal, single focus interventions will not achieve the targeted outcomes.

Trial registration

PROSPERO Registration CRD42016050086.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-019-1210-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aging in place, Community dwelling, Independent living , Health services, Community, Systematic review

Background

Interventions and services that enable people to remain living in their own home as they age are of great interest to older people, policy makers and the health and welfare sectors. The majority of older people choose to remain in their own homes for as long as possible, however this is often contingent on access to suitable support that is responsive to their changing needs [1–3].

Improvements in living standards and healthcare have led to people living longer, with increasing proportions of the population aged over 65 years [4, 5]. In the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries these demographic changes are predicted to at least double the long-term care costs for people aged over 65 years by 2050 [6].

Policy makers and aged care service providers are keen to understand interventions that can ease the pressure on the health and aged care sectors, and reduce the need for long-term residential aged care. In many developed countries there has been a shift from residential care to various models of community-based health and social care for older people. Government policies in many countries now focus on delaying or avoiding the need for long-term residential aged care through the development of person-centred, early intervention and preventative services such as in Australia [7], Sweden [8], New Zealand [9], and England [10].

Description of the intervention

A wide variety of community-based, aged care interventions have emerged in recent years aimed at supporting people in their homes and delaying or avoiding residential aged care (also known as residential care, nursing home). While all fit a broad category of preventative community aged care, it is challenging to understand the similarities and differences between these interventions as there is no agreed nomenclature, and the elements of the services provided are often poorly described. Very little is known about the effectiveness of any of these interventions.

Previous publications have attempted to categorize the various interventions in community aged care but confusion and overlap remains an issue. Interventions and approaches to care previously described include:

Centre-based wellness programs. Wellness has been defined as a multidimensional state of being, describing the existence of positive health in an individual as exemplified by quality of life and a sense of wellbeing [11]. Wellness programs are frequently run from community centres, with transport sometimes provided for participants to attend.

Re-enablement or restorative home care has been defined as a time-limited program (typically 6–12 weeks) involving multiple visits to a person’s home by multidisciplinary professionals. It aims to help older people regain functional independence [12]. In this review we will consider falls prevention interventions in this category even though they frequently run longer than 12 weeks.

Case management is a complex intervention usually provided by a central worker ([13],p1). The Case Management Society of Australia describes case management as “a collaborative process of assessment, planning, facilitation and advocacy for options and services to meet an individual’s holistic needs through communication and available resources to promote quality cost-effective outcomes” [14]. While there is no single definition of case management as practiced within aged community settings, several characteristics of case management in community aged care have been identified including: “a collaborative process with the family carer; employing a planned approach to achieve client outcomes with cost-efficiency; being based in the community aged care sector” ([15],p2).

Consumer directed care has been defined as “interventions where consumers were explicitly given choice and/or control of services” ([13],p3).

Complex interventions (e.g. multifactorial preventative home visits) is a term used to encapsulate a wide variety of services and complex, multifactorial, individualised interventions aimed at maintaining health and autonomy and preventing disability [16], with case management a key component.

In our analysis of the literature we divided studies into these sub-groupings where possible, but remained open to other sub-groupings that may become evident such as services targeting specific conditions or needs (e.g. dementia specific interventions).

Previous systematic reviews

Some previous reviews have explored interventions aimed at reducing residential aged care admissions including an earlier systematic review of systematic reviews conducted by Tourigny and colleagues (2015) [17]. These authors concluded that no reviews published prior to 2011 had demonstrated that preventative home visits avoid or delay residential aged care admissions.

An updated systematic review by Mayo-Wilson (2014) on preventative home visiting included evidence published to 2012 [18]. This meta-regression analysis of 26 randomised control trials (RCTs) did not find a significant reduction in the risk of being admitted to an institution by time point, age of participants, type of visitor or number of home visits.

Beswick and colleagues (2008) systematically reviewed RCTs assessing community-based multifactorial interventions for older people living at home and published prior to January 2005. They reported that these complex interventions reduced residential aged care admissions (relative risk 0.87, 95% CI 0.83–0.90), but not death (1.00, 0.97–1.02). The Beswick review did not provide information on the interventions or outcomes in individual studies and was therefore of limited value in informing other end users [19].

Objectives of this systematic review

No previous systematic review has itemised the elements of the interventions used in included RCTs, thereby limiting their ability to inform service providers and researchers regarding practical approaches to delivering effective care and services.

Therefore this comprehensive systematic review sought to update and synthesise evidence for the effectiveness of community-based, aged care interventions in delaying or avoiding admission to residential aged care for older adults. Secondary objectives were to report the effectiveness of these interventions in maintaining or improving other outcomes such as quality of life and mortality, and where possible, to itemise the elements used in the interventions.

Methods

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) in October 2016 (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016050086). We report the review in accordance with the PRISMA Checklist [20].

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only studies that reported the outcome of ‘remaining home or avoiding residential aged care’ were included. We considered any intervention design including RCTs, controlled trials, cohort studies, or case controlled studies, conducted in any country.

Types of participants

Adults 65 years or older, living in their own homes in the community. No restriction was placed on disease or health status.

Context

The context of interest was community living including metropolitan or rural communities, retirement homes and independent living units, but excluded residential aged care.

Intervention/exposure

Included studies considered any intervention, model, activity, service or program that promotes ‘aging in place’, when the ‘place’ is community (the person’s home). Interventions included those that aimed to prevent or address functional decline, or maintain wellbeing and independence in older adults.

Comparator/control

Studies with any or no comparator were considered.

Primary outcome

Avoiding residential aged care admission or time remaining at home.

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life outcomes, mortality, morbidity or independence measures such as the Barthel Index; Modified Rankine Score; participation levels; health and well-being measures (e.g. SF36); health adjusted QoL (health economic data); healthcare utilization (including hospital admissions); or adverse events.

Exclusion criteria

Non-English publications, qualitative studies, and studies on palliative care or end of life care.

Information sources

Electronic database searches were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Methodology Register, AMED, CINAHL and Ageline from January 2000 to February 2018.

Search

A research librarian helped develop a search string in MEDLINE (see Additional file 1), which was adapted for the other databases. The databases were searched, results were entered into Endnote folders, and any duplicates and irrelevant titles were removed (AW). Reference lists of relevant reviews were hand searched to identify additional potential studies.

Study selection

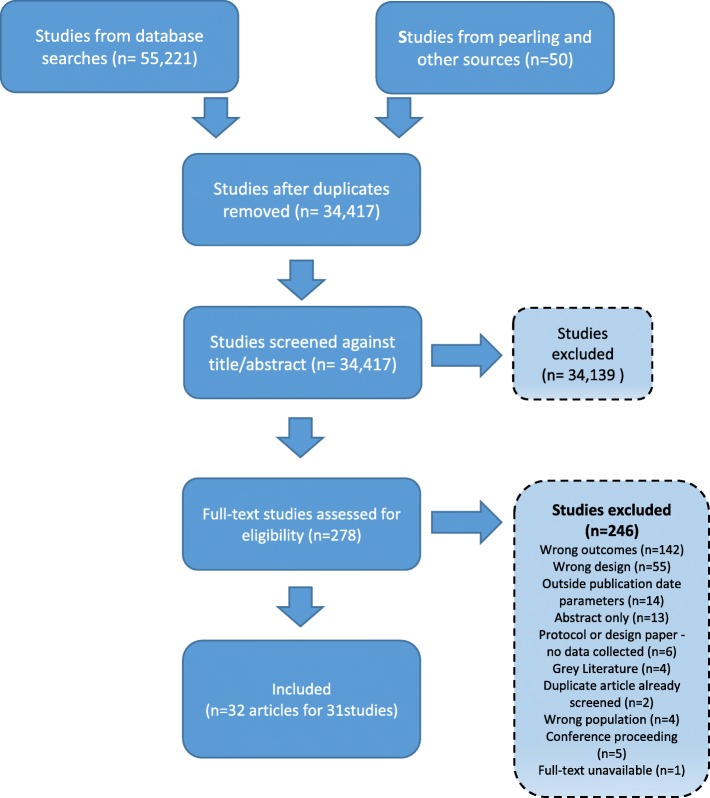

Study selection against the review’s criteria was managed within Covidence software (www.covidence.org/). Study selection was conducted in two phases independently by two reviewers (AW, JU, or JL). In the first phase all titles and abstracts were screened and studies were excluded if both reviewers agreed to exclude. Title/abstracts without consensus agreement underwent full-text screening. In the second phase of full-text screening, consensus was reached to include or exclude studies from the review and differences were resolved through discussion or by another author (SH). The reasons for full-text exclusion were recorded and the selection process was mapped in a PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection

Data collection

Data were extracted from included articles and entered into specifically designed spreadsheets. The following data fields were extracted: full citation, year, country and context of the research, study design, sample size, participant inclusion/exclusion criteria, intervention/s, controls, time period of intervention, outcome measures used, outcome time points, and outcome results. For six studies data had not been published in a form that enabled meta-analysis and these authors were contacted to request further data. This resulted in the inclusion of unpublished data from two author groups [21, 22].

Risk of bias for individual studies

Two reviewers (AW, ET or JL) independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool and reached consensus decisions. Assessment scored papers as high, low or unclear risk of bias in the following domains: randomisation sequence generation, concealment of allocation, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting. Risk of bias results are reported in Table 2 for information only as they did not influence exclusion from the review.

Table 2.

Risk of bias

| Author, year | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beland 2006 | L | ? | ? | L | L | ? |

| Byles 2004 | L | ? | H | L | L | ? |

| Caplan 2004 | L | H | ? | H | L | ? |

| Dalby 2000 | L | L | L | L | L | ? |

| Eloniemi-Sulkava 2001 | L | L | ? | L | L | ? |

| Eloniemi-Sulkava 2009 | L | L | ? | ? | L | ? |

| Gill 2002 | L | ? | ? | L | L | ? |

| Hammar 2007 | L | ? | ? | H | L | ? |

| Hebert 2001 | L | ? | L | L | L | ? |

| Holland 2005 | L | L | H | ? | L | ? |

| Kono 2004 | L | ? | L | L | L | ? |

| Kono 2012 | L | ? | ? | ? | L | ? |

| Lenaghan 2007 | ? | ? | ? | ? | L | ? |

| Luukinen 2007 | L | ? | ? | L | L | ? |

| Mahoney 2007 | L | L | ? | L | L | ? |

| Markle-Reid 2013 | L | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Nakanishi 2018 | L | L | H | H | L | ? |

| Newbury 2001 | L | L | H | ? | L | L |

| Pardessus 2002 | L | ? | ? | ? | L | ? |

| Phung 2013 | ? | ? | ? | L | L | ? |

| Rockwood 2000 | ? | ? | H | L | ? | ? |

| Samus 2014 | L | ? | H | L | L | ? |

| Scott 2004 | L | ? | ? | ? | L | ? |

| Senior 2014 | ? | L | H | L | L | ? |

| Shapiro 2002 | L | ? | H | H | L | ? |

| Sommers 2000 | L | ? | H | ? | H | ? |

| Spice 2009 | L | ? | ? | ? | L | ? |

| Stuck 2000 | L | L | ? | L | L | ? |

| Spoorenberg 2018 | L | ? | H | L | L | ? |

| Thomas 2007 | L | ? | H | H | L | L |

| van Hout 2010 | L | ? | H | L | L | ? |

| Vass 2005 | L | ? | H | H | L | ? |

Legend: H High risk, L Low risk? Unclear risk

Summary measures

We reported the review’s summary measures for residential aged care admission and mortality as risk difference and 95% confidence intervals (CI), and quality of life as standardised mean differences with random effects and 95% CI.

Data synthesis

Given the broad nature of this review, a high degree of heterogeneity between studies was anticipated and found, making narrative synthesis of the data the most appropriate method/approach for many studies. A meta-analysis was conducted where sufficient homogeneity existed between two or more studies, taking into consideration comparators, outcomes and assessment time-points. The synthesis also presents the findings for intervention sub-groups according to broad intervention types or target groups where possible.

For analysis of dichotomous outcomes, risk differences were calculated using the number of events within the overall participant number for each group. Risk differences give an absolute effect that is more readily interpreted to reflect the risk of an outcome across the two groups. For continuous outcomes we used standardized mean differences, calculated from the mean and standard deviation of each group outcome, to allow for some heterogeneity in the specific measures.

For both forms of outcomes we calculated 95% CI and provided levels of significance to allow for interpretation, as well as an evaluation of the statistical heterogeneity across the pooled studies using the I2 statistic. All calculations were performed in Revman 5.3 [23].

Results

A flow diagram (see Fig. 1) reports the selection process and reasons for exclusion.

Study selection

The database searches found 55,221 citations, and 50 citations were gleaned from hand searched reference lists and other sources. From these, 32 articles (reporting 31 trials) published between 2000 and 2018 met the review’s selection criteria (see Fig. 1).

The characteristics and summarized outcomes for included RCTs are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and summarized outcomes

| First author, date, country, study design | Inclusion criteria | No. of participants & mean age | Intervention | Duration of intervention & visit frequency | Outcomes & time period | Shortened results (intervention group c/f control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex interventions | ||||||

|

Beland 2006 Canada RCT (2 articles) |

Aged ≥64 years; community-dwelling; French or English; participating caregiver; functional disability; no pending RAC admission. |

SIPA n = 606 Control n = 624 82 years |

SIPA (System of Integrated Care for Older Persons): multidisciplinary teams with full clinical responsibility for delivering comprehensive community-based care & coordination across health and social welfare sectors | Average length of enrolment was 572 days over the 662 day trial |

Institutional admission, ED utilized, Skilled RAC utilized. Hospital utilized, Number in hospital waiting RAC placement Baseline & 12 months. |

Skilled RAC admissions →. Decreased waiting in hospital for RAC place. Utilization or costs for ED, or acute hospital →. |

|

Dalby 2000 Canada RCT |

Functional impairment or hospital admission or bereavement in the previous 6 mths; aged ≥70 yrs.; at risk of sudden deterioration in health; community dwelling; not involved in other studies or previous nurse visits. |

Intervention n = 73 (79.1 yrs) Control n = 69 (78.1 yrs) |

Nurse led assessment, care plan development and case management |

14 months Varied as needed by individual |

RAC admission; Health services utilization; ED visits; Hospital admissions Baseline, 14mths f/up. |

RAC admission →. Health services utilization, visits to ED or overnight hospital admissions →. |

|

Eloniemi-Sulkava 2001} Finland RCT |

Aged ≥65 yrs.; dementia; living at home with informal caregiver; no other severe diseases that might lead to institutionalization. |

Intervention n = 53 (78.8 yrs) Control n = 47 (80.1 yrs) |

Comprehensive, case managed dementia support for client and carer (nurse led) |

2 years Individualised frequency of contacts from once a month to 5 times a day. |

RAC admission; Deaths Baseline, 1 & 2 yr. f/up. |

RAC admission at 12 months was reduced. RAC admission at 2 yrs. → . Deaths →. |

|

Eloniemi-Sulkava 2009 Finland RCT |

Spouse caring for a partner with dementia at home; dementia diagnosis; no other severe disease with prognosis < 6 months. |

Intervention n = 63 (78 yrs) Control n = 62 (77 yrs) |

Comprehensive, case managed dementia support for client and carer (nurse & geriatrician led) |

Maximum2 yrs– varied phased recruitment Individualised, could be frequent contact |

Admitted to RAC Deaths Baseline, 6, 12 & 24 mths f/up. |

RAC admission at 12mths → . Reduced RAC admission at 18mths. RAC admission at 2 yrs. → . Deaths at 24 months →. |

|

Hammar 2007 Finland Cluster RCT |

Aged ≥65 years; discharged from hospital back home with home care services; primary admission diagnosis was not cancer, dementia or psychiatric; able to answer mental status-test |

Intervention n = 354 Control n = 314 81.7 yrs |

Generic community care and case management (IHCaD-practice) commencing with hospital discharge planning, and tailored to municipalities needs. |

6 month program Frequency unclear |

Admitted to RAC; Deaths; Finnish version of ADL; hospital care; HRQoL (NHP & EQ-5D) Baseline, 3 wks & 6 mths f/up |

RAC admission at 6mth → . Deaths at 6mths → . ADL change at 6mths → . The EQ-5D change at 6mths → . Hospital care at 3wks & 6mth → . |

|

Mahoney 2007 USA RCT |

Aged ≥65; independently living; history of 2 falls in past year, or 1 injurious fall in past 2 yrs., or gait & balance problems; caregiver in the home. |

Intervention n = 174 (79.6 yrs) Control n = 175 (80 yrs) |

Multi-factorial falls prevention intervention linking participants to existing medical care & service networks. |

12 month program 2 visits in-home first 3 weeks, then monthly phone contact |

RAC admissions; RAC days; Mortality; Barthel scores; Depression (GDS); Hospitalisation; Hospital days; Baseline, 12 mth f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Fewer RAC days per year. Hospitalisation →. Hospital days →. Barthel scores →. Mean change in GDS score →. |

|

Markle-Reid 2013 Canada RCT |

Trial 1: > 75 years; eligible for personal support services; not eligible for nursing. Trial 2: > 75 years; eligible for personal support services; at risk for falls. Trial 3: confirmed diagnosis of stroke or transient ischaemic attack in past 18 months; eligible for home care services |

Trial 1: Intervention n = 144 Control n = 144 83.8 yrs. Trial 2: Intervention n = 54 Control n = 55 84 yrs. Trial 3: Intervention n = 52 Control n = 49 74.3 yrs |

3 different health promotion, disease prevention interventions targeting functional decline and frailty |

Trial 1: 5 home visits over 6mths (nursing) Trial 2: median of 19.5 home visits by the interD team over 6mths Trial 3: median of 24 home visits by the interD team over 12mths |

Long term care (RAC) admissions; Mortality; SF-36 score; Depression (CES-D). Baseline, 6 & 12 mths f/up. |

Trial 1: RAC long-term care →. Mortality →. Improved SF-36 mental health & emotional components. Reduced depression. Number of falls →. Trial 2: RAC long-term care →. Mortality →. SF-36 scores →. Reduced falls Trial 3: RAC long-term care →. Mortality →. SF-36 scores →. Number of falls →. |

|

Nakanishi 2018 Japan Cluster-RCT |

Aged > 65 years; Home-living patients with diagnosed dementia |

Intervention n = 141 (83.7 yrs) Control n = 142 (84.9 yrs) |

Challenging behaviour dementia training for care professionals; assessment of client behaviours & unmet needs; action plan; individualised multi-D treatment; behaviour monitoring; case management |

6mth program Could have frequent contacts |

RAC placement; Mortality; Challenging behaviour (NPI-NH); Pain (Abbey pain scale); Cognition (SMQ); Barthel Index for ADLs; Medication use Baseline, 6mths |

RAC admission →. Mortality →. Challenging behaviours significantly improved in intervention group. Other outcomes →. |

|

Phung 2013 Denmark RCT |

Home-living patients diagnosed within the past 12 months with AD, mixed AD with vascular component or Lewy body dementia; ≥50 years; MMSE score ≥ 20; having one participating primary caregiver. All patients met DSM-IV criteria for dementia, NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable AD or McKeith criteria for Lewy body dementia. No severe somatic or psychiatric comorbidities |

Intervention n = 163 (76.5 yrs) Control n = 167 (75.9 yrs) |

Counselling, training, information and support for patients with mild dementia and their caregivers (DAISY) |

8-12mths program Phone contact every 3–4 weeks, 7 individual sessions, 5 group sessions |

Patients: RAC admissions; MMSE; Cornell Depression Scale (CDS); Health related QoL (EQ-VAS); QoL-AD; EuroQoL EQ-5D; Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPIQ); ADSC-ADLs; Mortality; Carers: Geriatric Depression Scale (GPS); Health related QoL (EQ-VAS); Baseline, 6, 12 & 36 mths f/up. |

RAC admission →. MMSE changes →. CDS changes →. EQ-VAS changes→. QoL-AD changes→. NPIQ changes →. ADSC-ADL changes →. Mortality →. |

|

Samus 2014 USA RCT |

Aged 70+ yrs.; English-speaking; community-residing; reliable partner; dementia or other cognitive disease; > 1 unmet need on JHDCNA; not in crisis (no signs of abuse, neglect, risk of danger to self/others) |

Intervention n = 110 (84.0 yrs) Control n = 193 (83.9 yrs) |

Interdisciplinary team case management, care planning, education & support for people with dementia (MIND) |

18mth program Monthly contact |

Days at home; RAC placement; Mortality; QOL-AD; ADRQL-40; QOL-AD-Informant; Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPIQ); Depression (CSDD) Baseline, 9 & 18 mths f/up. |

Increase in mean days at home. Reduced RAC placement or death. [RAC admit not reported separately] Improved self-reported QOL (QOL-AD). Proxy rated QOL (ADRQL-40; QOL-AD-Informant) → . NPS (NPI-Q), or participant depression (CSDD) Intervention →. |

|

Senior 2014 New Zealand RCT |

Age ≥ 65 years (≥55 years for Māori); at high risk of institutionalisation but not placed; communicate in English. |

Intervention n = 52 (81.9 yrs) Control n = 53 (83.6 yrs) |

Case-managed restorative care service delivered in short-stay residential aged care facilities and at participants’ residences (Promoting Independence Programmes) |

2 yr. program Could have frequent contacts |

RAC placements; Deaths Baseline, 24 mths f/up. |

RAC placements →. Deaths →. |

|

Shapiro 2002 USA RCT |

Elders on a waiting list for community aged care; scored moderate risk based on Axs of chronic health conditions, ADL limitations, & other measures of physical & psychological impairment. |

Intervention n = 40 (77.7 yrs) Control n = 65 (77.1 yrs) |

Case managed, early intervention social service program for low-income elders |

18mth program Monthly contact |

Institutionalised (RAC admission); Deaths; Depression (12-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale) Baseline, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15 & 18 mths f/up. |

RAC admission →. Death →. Improved OR for RAC admission or death. Depression →. |

|

Spoorenberg 2018 Netherlands RCT |

Age > 75 years; registered with a participating GP; not receiving other integrative care |

Intervention n = 747 (80.6 yrs) Control n = 709 (80.8 yrs) Stratified by risk profile |

Individualised program to maintain health & independence. Case managed, care plans, self management, information sessions, targeted support (EMBRACE) |

12 mths Could be frequent contacts |

Institutionalised (RAC admission); Deaths; Health status (EQ-5D-3 L, INTERMED-E-SA, GFI, Katz-15); Wellbeing (GWI, QoL); Self management (SMAS = 30), PIH-OA) Baseline, 12mths |

RAC admission →. Death →. Deterioration in ADLs in intervention group (p = 0.04) Other health status → Wellbeing →. Self management →. |

| Single focus interventions | ||||||

|

Byles 2004 Australia RCT |

Veterans or war widows with full entitlements from DVA; aged ≥70 years; community dwelling. |

Intervention n = 942 Control n = 627 |

Annual or 6 monthly in-home assessments, provision of health materials, and report and liaison with GP. | 3 year program |

Permanent admission to a RAC; deaths; SF-36 scores; Hospital admissions; Baseline, 1 yr., 2 yr. & 3 yr. f/up. |

Increased permanent RAC admission. Number of deaths →. SF-36 scores →. Hospital admission →. |

|

Gill 2002 USA RCT |

Aged ≥75 years; community dwelling; physically frail; can walk; speak English; MMSE score ≥ 20; life expectancy of > 12 mths; no major health event <6mths |

Intervention n = 94 (82.8 yrs) Control n = 94 (83.5 yrs) |

Home exercise program led by physical therapist to improve mobility and balance |

6 month program 16 visits over 6 months - varied |

RAC admissions; Deaths; Baseline, 3, 7 & 12 months f/up |

RAC admission by 12 mth f/up →. Number of days spent in a RAC by 12mths → . Deaths during 12 mth → . |

|

Hebert 2001 Canada RCT |

On Quebec Health Insurance Plan list; Aged > 75 years; community dwelling; born between 1 December & 30 April; spoke English or French |

Intervention n = 250 (80.2 yrs) Control n = 253 (80.3 yrs) |

Nursing assessment, report and recommendations to GP, monthly phone review |

1 year program Monthly contact |

Admitted to RAC; Health service utilization; Functional Measurement Autonomy (SMAF); General Wellbeing Schedule (GWBS); Social provisions scale (SPS); Deaths Baseline, 12 mths f/up. |

Admission to RAC → . Mean scores in SMAF, GWBS, SPS → . Deaths Intervention →. Health service utilization →. |

|

Holland 2005 UK RCT |

Aged ≥80 yrs.; emergency hospital admission; discharged to own home or warden controlled accommodation; prescribed ≥2 drugs on discharge; no dialysis treatment. |

Intervention n = 429 (85.4 yrs) Control n = 426 (85.5 yrs) |

Home visit for medication review and education by pharmacist following hospital discharge |

6–8 week program 2 visits |

RAC admissions; Mortality; EQ-5D (QoL); Emergency readmissions; Baseline, 3 & 6 mths f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Reduced emergency readmissions. Increased GPs home visits. Deaths →. Change in QoL EQ-5D scores →. |

|

Lenaghan 2007 UK RCT |

> 80 years; living in own home; prescribed ≥4 daily medicines; & ≥ 1 criteria present: living alone; mental confusion vision; hearing impairment;prescribed medicines associated with medication-related morbidity; or prescribed > 7 regular oral medicines. |

Intervention n = 68 (84.5 yrs) Control n = 66 (84.1 yrs) |

Home visits by pharmacist for medication review and education | 2 visits in 8 weeks |

RAC admissions; Deaths; EQ-5D (QoL) Unplanned hospital admissions Baseline, 6 mths f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Deaths →. The EQ-5D scores →. Unplanned hospital admissions →. |

|

Luukinen 2006 Finland RCT |

Home dwelling; history of recurrent falls in past year, or at ≥1 risk factor for disability in ADLs or mobility. |

Intervention n = 243 Control n = 243 88 yrs |

Community exercise program to prevent disability |

18–24 month program Bimonthly contact |

RAC admission; Mobility score; Balance impairment; ADL Baseline, end of intervention & f/up. |

RAC admission →. Severe mobility restrictions at f/up →. Reduction in impaired balance. Improved mobility scores. ADL score improvement →. |

|

Newbury 2001 Australia RCT |

≥75 years; attending 1 of 6 GP practice sites; community dwelling; no dementia diagnosis |

Control n = 50 (80.76 yrs) Intervention n = 50 (78.96 yrs) |

Two annual 75+ Health Assessments with report back to GP |

2 year program Annual assessments |

Institution (RAC) admissions; Barthel ADL; Self-rated health; Deaths; Folstein MMS; GDS 15; SF-36 Baseline, 12 mths f/up. |

RAC admission →. Barthel ADL → . Self-rated health →. Deaths →. Folstein MMS Intervention →. GDS 15 Intervention →. SF-36 → . |

|

Pardessus 2002 France RCT |

Aged ≥65 yrs.; hospitalized for falling; discharged home; no cognitive impairment; fall not secondary to medical or therapeutic problems; access to phone. |

Intervention n = 30 (83.51 yrs) Control n = 30 (82.9 yrs) |

Single occupational therapy home visit to address risk of falls |

12mth program 1 x home visit |

RAC admissions; Functional autonomy measurement system (SMAF); Total ADL; Total IADL; Recurring fall; Hospitalization for fall; Hospitalization for another cause; Deaths Baseline, 6 & 12 mths f/up |

RAC admission →. Total SMAF 6–12 months Intervention →. Total ADL scores at 6 or 12mths → . Total IADL scores at 6 or 12mths → . Total SMAF at 6 or 12mths → . Recurring fall →. Hospitalization for fall →. Hospitalisation for another cause →. Death →. |

|

Spice 2009 United Kingdom Cluster RCT |

Aged ≥65 yrs.; community living; ≥2 falls in previous year; not presenting to ED with most recent fall; life expectancy > 1 yr.; abbreviated mental test score ≥ 7; English speakers. |

Controls n = 159 (83 yrs) Primary care n = 136 (83 yrs) Secondary care n = 210 (81 yrs) |

Primary care intervention group – GP assessment to identify falls risk; referrals as needed. Secondary care intervention group - multi-disciplinary Day Hospital falls prevention assessment with referrals as needed |

12 months Monthly contact |

RAC admissions; Falls; Fall-related hospital admissions; Mobility (Get up & go test) Baseline, 12 mths f/up. |

Admission to RAC → Reduced falls.in Secondary Care Gp. Falls in Primary Care Gp → . Mobility score →. Fall-related hospital admissions →. |

|

Thomas 2007 Canada RCT |

Aged ≥75 years; no formal home care services; receiving informal care; not in RAC or other long term care; has a primary caregiver; English speaking; mentally competent. |

Intervention (1) n = 175 (80.7 yrs) Intervention (2) n = 170 (80.4 yrs) Control n = 175 (80.7 yrs) |

Annual functional assessments with either (1) elders and carers only given results only, or (2) also offered help with referrals |

4 year program Annual contact |

Institutional (RAC) admissions; Deaths; Self-efficacy; Self-rated health status; Caregiver burden Baseline, yr1, yr2, yr3, yr4. |

RAC admissions →. Deaths →. Self-efficacy →. Self-rated health status →. Caregiver burden →. |

|

Vass 2005 Denmark RCT |

Aged 75-80 yrs.; Non-institutionalised; |

Intervention n = 1798 Control n = 1688 75 yr. and 80 yr. cohorts |

Educational program for healthcare professionals and GPs in geriatric assessment and recognising early functional decline |

3 year program 6 monthly contact |

RAC admissions; Mortality; Functional ability Baseline, 3 yr. f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Mortality →. Improved functional ability in the 80 yr. old. Improved functional ability in the 75 yr. olds. |

| OTHER RCTs (not clearly complex nor minimal interventions) | ||||||

|

Caplan 2004 Australia RCT |

Aged ≥75 yrs.; discharged from ED; community dwelling. |

Intervention n = 370 (82.1 yrs) Control n = 369 (82.4 yrs) |

In-home assessment following ED presentation, with 28 days community support from hospital-based MultiD team | 4 weeks |

RAC admission; ED admission; Hospital admission; Mortality. Baseline, 3, 6, 12 & 18 months f/up. |

RAC admission →. Reduced emergency admission to hospital. Increased time to first ED admission. Mortality →. |

|

Kono 2012 Japan RCT |

Aged ≥65 years; need support to live at home; living at home; not used formal long-term care services for the past 3 months. |

Intervention n = 161 (80.3 yrs) Control n = 162 (79.6 yrs) |

Routine preventive home visits 6 monthly | Every 6 months for 2 years |

Institutional admissions (RAC or group home); Deaths; Admitted to hospital; Decline in ADLs; Depression Baseline, 1 & 2 yr. f/up |

Institutionalized at 2 yr. → . Deaths at 2 yrs. → . Hospital admissions →. Less decline in ADLs ability. Reduced depression. Increased utilisation of community long-term care. |

|

Kono 2004 Japan RCT |

Aged > 65; living at home; walk independently; need some assistance to live in the community; went outdoors <3x/wk. |

Intervention n = 59 (82.5 yrs) Control n = 60 (82.9 yrs) |

Preventive home visits by public health nurses 3 monthly | Home visits every 3 months for 18 months |

Living at home; RAC admissions; Mortality; ADLs; Social support; Functional status Baseline, 18 mths f/up. |

Living at home →. Admitted to RAC → . Deaths →. Less declining ADLs. Social support →. |

|

Rockwood 2000 Canada RCT |

Frailty (concern about community living, or recent bereavement, or hospitalization, or acute illness); frequent physician contact; multiple medical problems; polypharmacy; adverse drug events; functional impairment or functional decline; diagnostic uncertainty. |

Intervention n = 95 (81.4 yrs) Control n = 87 (82.2 yrs) |

Implementation of Comprehensive Geriatrician Assessment recommendations by a mobile geriatric assessment team. |

3mth program Range 1–6 contacts |

RAC admissions; Goal Attainment Scale (GAS); Deaths Baseline, 3, 6 & 12 mths f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Improved Goal Attainment (GAS). Deaths →. |

|

Scott 2004 USA RCT |

Aged ≥60 yrs.; ≥ 11 outpatient clinic visits in the prior 18 months; ≥1 chronic conditions; able to attend clinic; no serious cognitive impairment. |

Intervention n = 14 (74.2 yrs) Control n = 149 (74.1 yrs) |

Monthly group meetings for education, support & health review led by patients’ GP and a nurse |

2 yr. program Monthly contact |

Skilled nursing facility (RAC) admissions; Hospital admissions; Pharmacy services; Health facility visits; ADLs; Self-reported Quality of life; Baseline, 24 mths f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Reduced hospital admissions. Reduced emergency visits. Improved self-reported quality of life. Increased self-efficacy. ADLs →. Pharmacy services →. Hospital outpatient visits →. |

|

Sommers 2000 USA Cluster RCT |

Aged > 65; not in RAC; 1+ visit to GP past 3mths; English speaking; Indep in mobility toileting feeding; Dependant in 1+ IADL; 2+ chronic conditions; not terminally ill; no dementia or metastatic disease. |

Intervention n = 280 (77 yrs) Control n = 263 (78 yrs) |

Collaborative care from a GP, nurse and social worker for chronically ill elders (chronic disease self-management model) |

3 yr. program Contact at least 6 weekly |

RAC admissions; Symptom scale; SF-36; Health Activities Questionnaire (HAQ); Depression (GDS); Medication count; Nutrition checklist; Hospital admissions; GP office visits; Deaths; Social activities; Baseline, yr1 & yr2 |

RAC admissions →. Reduced hospital admissions. Fewer GP office visits/yr. Symptom scale, SF-36, HAQ, GDS, Medication count and Nutrition checklist Intervention →. Deaths →. |

|

Stuck 2000 Switzerland RCT |

Community living; Age 75+; German speaking; not terminal disease |

Intervention n = 264 82 yrs. Control n = 527 81.5 yrs |

Annual geriatric assessments with quarterly preventative home visits by a nurse |

3 yr. program 3 monthly contact |

RAC admissions; Functional status; Mortality Baseline, 1 yr., 2 yr., 3 yr. f/up. |

RAC admissions →. Dependent in ADL or iADLs →. Mortality →. |

|

Van Hout 2010 The Netherlands RCT |

Aged ≥75 yrs.; living at home; meet criteria for frailty |

Intervention n = 331 (81.3 yrs) Control n = 320 (81.5 yrs) |

Geriatric assessments by nurses, personalized care plans and preventative home visiting |

18mth program 3 monthly contact |

Institutional (RAC) admissions; Deaths; Hospital admissions; SF-36; ADL; IADL; Emergency visits Baseline, 6 & 18 mths f/up. |

RAC admission →. Death →. Hospital admissions →. Emergency visits →. ADLs & iADLs →. |

→ Indicates no significant difference between outcomes of intervention and control groups

AD-Alzheimer’s disease; ADL-activities of daily living; ADRQL-40-Alzheimer’s Disease Rated Quality of Life-40 item; ADSC-ADL-Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Scales; CDS-Cornell depression scale; CES-D-Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; CSDD-Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; DSM-IV- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders version 4; DVA-Department of Veterans Affairs; ED-emergency department; EuroQoL - A generic utility measure used to characterize current health states; EQ-5D-EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire; EQ-5D-3 L -EuroQoL-5D-3 level version; EQ-VAS-EuroQol Visual Analogue Scales; Folstein MMS-Folstein Mini-Mental State; GAS-goal attainment scale; GDS-geriatric depression scale; GFI −15 item measure of frailty; GP-General Practitioner; GWBS-general wellbeing schedule; GWI –Groningen Wellbeing Index; HAQ-health activities questionnaire; IADL-instrumental activities of daily living; IHCaD-practice-generic prototype of care/case management-practice; INTERMED-E-SA – measure of complexity of care needs; Katz-15 – meaure of ADL limitations; MMSE-mini-mental state examination; Multi-D-multidisciplinary; JHDCNA-Johns Hopkins Dementia Care Needs Assessment; RAC-Residential Aged Care; NINCDS-ADRDA- National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association; NPIQ -Neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire; NPI-NH -Neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire fro Nursing Homes; OR-odds ratio; PIH-OA –Partners in Health Scale; QoL-quality of life; QoL-AD -Quality of Life Scale for Alzheimer’s disease; RCT-randomised control trial; SF-36-36-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form; SIPA-System of Integrated Care for Older Persons; SMAF-functional measurement autonomy system; SMQ –Short Memory Questionnaire; SMAS – Self-Management Ability Scale; SPS-social provisions scale

Types of control conditions

Most RCTs described their control groups as receiving ‘usual care’. This was not explained in any detail and is likely to have differed across settings and across the 11 countries where the research was conducted (Canada, Finland, the United States (US), Japan, Denmark, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Australia, United Kingdom (UK), France, Switzerland). Four studies provided augmented usual care for control group participants such as additional educational and resource materials [24, 25], an education program [26], or an occupational therapy home assessment [27].

Types of interventions and targeted participants

The majority of RCTs aimed to support older community-dwelling people who were at risk of functional decline and residential aged care admission. Some trials targeted people with specific conditions or risk factors such as dementia [24, 25, 28–30], recurrent falls [21, 27, 31–33], transition from hospital to community [32, 34–36], or polypharmacy [36–38].

Details of intervention elements were extracted from RCTs and entered into a table to assist our understanding of the studies’ interventions. This can be found in Additional file 2. While the types of interventions varied greatly and were frequently reported in very little detail, we were able to allocate many studies, but not all, to sub-groups. Most of these sub-groups are defined or described earlier under ‘Description of the intervention’. In addition we decided to consider the effect of complex interventions compared to minimal/simple interventions. Complex interventions (e.g. multifactorial preventative home visits) addressed multiple issues with case management, multi-disciplinary input and multiple participant contacts during the program. Complex intervention appeared to provide a higher intensity intervention (more elements of care and/or frequency of contact) than that provided in single focus intervention programs. Single focus interventions were provided by a single discipline, focused on one area of care and/or had very few participant contacts (e.g. an assessment with report to the general practitioner (GP), short term exercise program by a physiotherapist). The intervention sub-groups of studies were:

Complex interventions. Thirteen RCTs (14 articles), with a total of n = 5,694 participants [21, 24, 25, 27–30, 34, 39–44].

Single focus interventions. Eleven RCTs, with a total of n = 8,926 participants [22, 26, 31–33, 36, 37, 45–48].

Re-enablement or restorative care. Seven RCTs (8 articles), n = 2,842 participants trialled interventions targeting people who had falls [21, 27, 32, 33]), broader mobility issues [26], or aimed for more general functional restoration [39, 40, 43]. Four of these RCTs (five articles) also appear in the complex intervention sub-group, and three in the minimal intervention sub-group.

Dementia specific interventions. Four RCTs specifically targeted people with dementia and their family carers. Four of these studies fitted our criteria for complex interventions [24, 25, 28, 30]. One dementia study did not provide case management or refer participants to external support services, but did provide semi-individualised counselling, training and information to support people through the early months after dementia diagnosis [29].

No RCTs were found that tested ‘centre-based wellness programs’ or ‘consumer directed care’ as defined earlier under ‘Description of the intervention’.

All complex intervention studies identified case management as an element of the intervention they trialled, and so we did not analyse case management as a separate sub-group (case management usage within interventions can be found in Additional file 2).

Of the seven RCTs not allocated to a sub-group, one delivered a comprehensive chronic disease self-management intervention [49], one investigated support for the transition from hospital to community [35], one investigated GP led monthly group education and support meetings [50], and four others provided insufficient information about their intervention to enable sub-group allocation. [38, 51–53].

Types of outcomes

All studies reported our primary outcome of admission to residential aged care during the study period. In addition two studies reported the outcome as days remaining at home [25], and days spent in residential aged care [27]. Some studies did not report the data in a form suitable for meta-analysis. In these cases we attempted to contact the original authors to request the data needed.

Secondary outcomes that were most commonly reported were considered in meta-analyses, these being mortality (reported in all RCTs), and various measures of quality of life reported in 12 studies [21, 25, 29, 34, 36, 37, 44–47, 50, 54].

Other outcomes are reported as narrative synthesis and in Table 1, including health service usage, functional ability, depression, mobility and falls, self-efficacy, and goal attainment.

Risk of bias within RCTs

Appraisal of research quality revealed mixed risk of bias across the RCTs (see Table 2). Unfortunately the reporting in many articles was inadequate to determine whether or not risk of bias criteria had been met. Given the nature of the interventions, very few RCTs (9%) had been able to blind their participants and personnel to group allocation, however it was disappointing that blinding of outcome assessors was only reported in 51% of articles. Evidence of a low risk of bias from the randomization process was clear in only 29% studies; the concealment of group allocation was rarely reported. Accounting for all data had been of low risk in all but two studies, however only one study gave assurance that all outcomes had been reported as per their original protocol.

Results from RCTs

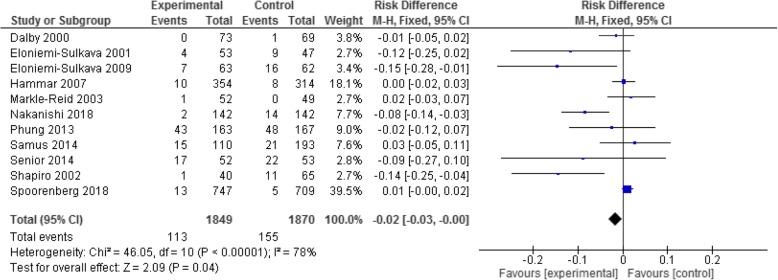

A summary of effectiveness for individual studies is provided in Table 1 and in the Forest Plots (Fig. 2 and Additional file 3).

Fig. 2.

All interventions – outcome of residential aged care admissions

Meta-analysis results

Residential aged care admission outcomes

Twenty eight studies provided the relevant data to allow a meta-analysis for the primary outcome of residential aged care admission rates. An initial analysis of risk difference for all interventions together (compared to the control ‘usual care’) revealed no difference in risk of admission between the two groups (total admissions 360 from 7,469 participants in the intervention group, and 401 from 7,177 in the control group; RD -0.00 (95% CI -0.01, 0.0, p = 0.23; moderate heterogeneity I2 = 51%). See Fig. 2 for the complete forest plot.

Intervention sub-group analysis of residential aged care admission

Meta-analyses were also run for four sub-groups of (1) complex interventions (11 studies had appropriate data), (2) single focus interventions (11 studies), (3) dementia specific interventions (5 studies), and (4) restorative programs (5 studies).

Considering the difference in risk of residential aged care admission in the intervention sub-groups: firstly for complex interventions the risk difference was significantly lower for the intervention participants by the order of 2% (RD -0.02; 95% CI -0.03, − 0.00; p = 0.04; I2 = 78%). This is illustrated in the Fig. 3 forest plot.

Fig. 3.

Complex interventions - outcome of residential aged care admissions

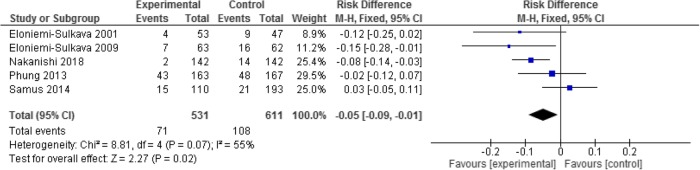

In the sub-group of dementia-specific programs, pooling the five studies showed a significant 5% risk reduction for residential aged care admission in the intervention group (71/531 participants), compared to the controls (108/611 participants) (RD -0.05; 95% CI -0.09, -0.01; p = 0.02; I2 = 55%) (See the forest plot in Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Dementia specific interventions – outcome of residential aged care admission

In contrast, the single focus intervention participants in 11 studies had no difference in risk of admission compared to the control (RD 0.00; 95% CI -0.01, 0.01; p = 0.71; I2 = 38%).

Restorative programs for people transitioning from hospitalisation to home, or at risk of falls (five studies) showed less residential aged care admission (53 from 445 participants) compared to control (65 from 446), however this was not significant (RD -0.03, 95% CI -0.07, 0.02; p = 0.23; I2 = 45%) (see forest plot in Additional file 3).

Mortality outcomes

Considering the secondary outcome of mortality, pooling 32 studies showed overall there was no difference in risk of dying between the intervention groups (deaths for all interventions combined 957/8,731, compared to controls 947/8,435) (RD -0.00; 95% CI -0.01, 0.01; p = 0.45; I2 = 1%) (see forest plot in Additional file 3). Sub-group analyses revealed no difference in mortality rates between any of the grouped interventions compared to the controls.

Quality of life outcomes

Quality of life was measured across a sufficient number of studies (n = 7) to warrant meta-analysis. Firstly considering all interventions compared to control, there was a standardized mean effect of 0.51, however this just failed to reach significance (95% CI -0.06, 1.09; p = 0.08) (see forest plot in Additional file 3). This included seven studies, with a total of 3,219 participants, but an I2 = 98% that is unacceptably high. We used random effects in response to this and also conducted a sensitivity analysis which revealed this was accounted for by one study reporting a stronger than usual effect in favour of the intervention group [25]. This was also the only intervention in the complex intervention sub-group analysis and not surprisingly showed a standardized mean difference of 3.38 (95% CI 3.02, 3.74; p < 0.000001).

In the sub-group of dementia-specific programs, quality of life outcomes from only one study were able to be analysed [25]. In this study the intervention group reported significantly improved quality of life compared to the control group (SMD 3.38, 95% CI 3.02, 3.74; p < 0.00001). (See forest plots in Additional file 3).

Duration of program

The duration of programs varied considerably. Interventions for studies within the complex intervention sub-group ranged from 6 months to 2 years duration (6 from 13 studies were > 18 months). The complex intervention RCTs with the strongest results for reducing residential aged care admission had data endpoints of 18 months to 2 years [24, 28, 41, 43]. Minimal intervention programs ranged from 8 weeks (medication reviews) to 4 years duration (the intervention being an annual assessment). More detail is available in Table 1 and Additional file 2: Table S1.

Narrative synthesis of other RCT outcomes

Here we describe narratively outcomes that could not be examined by meta-analysis. The results are equivocal for these outcomes and further evidence is required before conclusions can be drawn on effectiveness.

Health service usage outcomes

In 10 RCTs from all intervention sub-groups (in 11 articles), there was no significant difference in health service usage, such as hospital admissions or emergency department attendance, between intervention groups compared to the controls [27, 31, 32, 34, 37, 39, 40, 42, 45, 46, 53, 54]. In contrast four trials with differing interventions reported significant reductions or shifts in health service usage: three in favour of intervention in reducing usage and one in favour of the control group.

Caplan et.al. [35] reported 44.4% of their intervention group versus 54.3% of the control group had an emergency hospital admission over 18 months [Difference % (95% CI)] -9.9 (− 17.1 to − 2.7) p = 0.007.

Scott et.al. [50] reported utilization as mean (standard deviation) hospital admissions per patient over 24 months, with significantly less utilization in the intervention group 0.44 ± 0.89 compared to controls 0.82 ± 1.7 (p = 0.013).

Sommers et al. [49] reported over a 1 year period hospital readmissions for participants in the intervention group decreased from 6 to 4%, while the rate increased in the control group from 4 to 9% (p = 0.03)

Holland et al. [36] reported a shift in health service utilization. At 6 months 234 hospital readmissions had occurred in the intervention group versus 178 in the control group (rate ratio = 1.30, (95% CI 1.07 to 1.58), p = 0.009. Concurrently GPs carried out 204 home visits in the intervention group and 125 in the control group, a difference of 43% (rate ratio = 1.43 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.80), p = 0.002).

Functional ability outcomes

Of the 13 studies reporting functional outcomes such as activity of daily living (ADL) measures, ten were unable to show significant difference between intervention and control group outcomes [27, 29, 32–34, 46, 47, 50, 51, 54]. Three studies, with differing interventions, did report significantly better functional outcomes in the intervention group compared to controls:

In their small, initial study which was not clearly a complex nor a minimal intervention, Kono and colleagues [52] showed that intervention group subjects were less likely to show a decline in ADLs than control group subjects (p = .033).

In their later RCT Kono’s group reported that for participants who had some dependency at baseline, those in the intervention group were significantly less likely to deteriorate over 2 years in their functional ADLs (p = .0311) or IADLs (p = .0114), compared to controls [53].

Vass and colleagues [22] reported in their minimal intervention study that 85 year olds in their intervention group had better functional ability after 3 years than those in the control group [Odds Ratio 1.53 (95% CI 1.12–2.09), p = 0.008]; however there was no significant effect in younger participants.

Depression outcomes

Seven studies with differing types of interventions, considered measures of depression. Five of these reported no significant differences between intervention and control groups at follow-up [25, 27, 41, 47, 49]. Positive effects on depression were reported by two studies:

Kono and colleagues [53] reported that for participants who had some ADL dependency at baseline, those in the intervention group (which was not clearly a complex nor a minimal intervention) were significantly less likely to deteriorate over 2 years in relation to experiencing depression (p = 0.0001)

In one complex intervention arm conducted by Markle-Reid et.al. [21], intervention group participants had a statistically significant reduction in the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score than controls (− 2.72 (95% CI − 0.39 to − 5.07)), p = 0.022.

Mobility, balance, falls outcomes

No significant between-group differences were reported for the number of falls over 12 months in two RCTs [21, 32]. Spice and colleagues [31] reported no between-group mobility score differences. In contrast the 2006 study by Luukinen et.al. of a community exercise program (minimal intervention) reported positive change in mobility performance for the intervention subjects compared with the control (p = 0.013) and impaired balance affected fewer intervention subjects (45%) than controls (59%) (p = 0.015). Elements of the interventions differed across these studies [33].

Self-efficacy outcomes

Self-efficacy was measured in two trials. Thomas and colleagues [48], reported no significant group differences in self-efficacy outcomes in their minimal intervention trial, while Scott et.al. [50] reported a better self-efficacy rating only for ‘communication with their physician’ for the intervention group compared to controls (p = 0.03).

Goal attainment outcomes

The Goal Attainment Scale was used by Rockwood et.al. [38]. At 3 months follow-up the intervention group was more likely to have attained their goals, than the control group (p < 0.001).

Discussion

In this paper we have systematically reviewed the published evidence of interventions to avoid or delay residential aged care admissions for older people living in the community, thus achieving our study objectives. This is the first known review to provide information on the elements of interventions and programs tested in published RCTs, and thus guide policy makers and healthcare providers on implementation of the more effective interventions.

It is clear that to reduce the risk of residential aged care admission requires multifactorial complex interventions as there is no evidence of significant effect from more minimal, single focus interventions. Furthermore, our meta-analysis has shown that complex interventions can reduce the risk of residential aged care admission for people with dementia. Given the complexity of aging with chronic health conditions including dementia, it is perhaps not surprising that interventions need to be multifaceted and complex in order to be effective. Within the context of an aging population it becomes even more important to understand which complex interventions are successful and which facets are necessary for success.

The most common elements in the complex intervention studies were the use of a comprehensive assessment process with good communication and liaison with GPs, individualised care plans and interventions with frequent client contact if required and regular reviews. Careful case management that included referrals to services not provided within the study intervention was also a common feature. In addition, developing skills and capacities within clients and/ or carers through education and training was a part of many complex intervention studies. What is less clear is who is best placed to deliver the assessment and case management, or whether there needs to be a multidisciplinary approach to service delivery. The complex intervention RCTs with the strongest results for reducing residential aged care admission had longer data endpoints (18 months to 2 years). It is likely that complex interventions need to be delivered over long time-frames to be influential and that follow-up at 18 months or longer is needed to capture effectiveness outcomes. The effectiveness of complex intervention may not attenuate over time.

While single focus interventions did not show a significant effect in reducing residential aged care admission, many of them showed a trend towards reducing admission and could be considered as elements within a multifactorial intervention project in future research. Examples were in-home medication reviews by a pharmacist [36], home safety assessments by occupational therapists [32], and mobility exercise programs by a physiotherapist [26]. A comprehensive complex intervention is likely to include similar specific interventions to the examples given.

Only five of 13 complex intervention studies specified that clients/carers were involved in decision making. The reporting quality of some studies may have failed to document a shared decision making process that had actually occurred. It is surprising that more emphasis has not been given to involvement of clients and/or carers in decision making given the emphasis in many policies and the preference for involvement demonstrated in other literature. It is likely that shared decision making will be required by future generations of older people as more informed consumers with higher expectations of services come to require service provision. Shared decision making fits with consumer driven models and optimises autonomy for clients and their support network [55]. Future studies could compare the outcomes for those specifically involved in shared decision making and planning with those who are not.

Consistent with earlier systematic reviews [56], our meta-analysis found no significant effect on mortality rates from any type of intervention. It may be that follow-up timeframes were too short to fully establish the impact of complex community interventions on extending survival days.

The only complex intervention studies that produced significantly better quality of life outcomes was one that focused on participants with dementia. Quality of life for people living in the community with dementia is known to be a complex and often distressing issue, and difficult to address [57]. Earlier studies have reported associations in this group between poor quality of life and unmet needs [58], including an inability to perform activities of daily living [59]. Individualised complex interventions similar to those in our included studies would appear to be a best-practice option for people with dementia.

Limitations

As usual this systematic review may be affected by unknown publication bias. It is certainly limited by the methodological deficiencies in most of the included studies. Only one RCT demonstrated an overall low risk of bias and the remainder either had a high risk of bias or provided insufficient detail to determine bias. We note that considerable heterogeneity exists in several of the meta-analyses which suggests caution is needed when interpreting some results. There was insufficient detail in several included studies to fully understand the details of the intervention and/or the control conditions at a level that could be replicated. Future studies require careful planning and attention to risk and detailed reporting in order to strengthen the evidence base.

We did not search studies published in non-English journals or grey literature which may have caused us to miss relevant studies. We did not attempt a cost-effectiveness analysis – indeed there appears to be little evidence in the extant literature.

Conclusions

Available evidence showed that multifactorial complex interventions in community aged care can significantly improve older adults’ ability to remain living at home and avoid residential aged care admission. While minimal or single focus interventions did not have a significant effect on delaying residential aged care admission, the direction of risk reduction in many of these studies favoured the intervention group.

There was no evidence of a significant effect on mortality rates or quality of life from any type of intervention compared to the controls, except a single study finding in favour of intervention for people with dementia.

Future studies are needed to investigate the specific components and costs of multifactorial community aged care interventions that are crucial in avoiding or delaying residential aged care admission for older adults, and that meet the preferences of older adults.

Additional files

Medline search string. (DOCX 12 kb)

Table S1. Intervention elements. (DOCX 24 kb)

Additional forest plots. (DOCX 266 kb)

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Carole Gibbs for assistance designing the database searches, and Esther Tian who assisted with risk of bias assessment in this review.

Abbreviations

- ADL

Activity of Daily Living

- CI

Confidence Interval

- GP

General Practitioner

- PROSPERO

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- QoL

Quality of Life

- RCT

Randomised Control Trial

Authors’ contributions

Conception of the review: SH, JL, AMW, MS. Design of the review: JL, SH, AW, MS. Acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data: AW, JL, SH, JU. Drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: JL, MS, SH, AW, AMW. Final approval of the version to be published: all authors. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: JL, SH. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This review was supported by funding from ECH Inc. who commissioned the review however this funding body was not involved in the analysis or interpretation of the review.

Availability of data and materials

All data extracted or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

One author (AMW) is an employee of ECH Inc. and participated in conceptualising the scope of the review, and in the final editing of the manuscript. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Julie A. Luker, Email: julie.luker@unisa.edu.au

Anthea Worley, Email: anthea.worley@unisa.edu.au.

Mandy Stanley, Email: m.stanley@ecu.edu.au.

Jeric Uy, Email: jeric.uy@unisa.edu.au.

Amber M. Watt, Email: awatt@ech.asn.au

Susan L. Hillier, Email: susan.hillier@unisa.edu.au

References

- 1.Productivity Commission . Housing decisions of older Australians. Canberra: Productivity Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutchin MP, Coppola S, Talley V, Svihula J, Catelier D, Shank KH. Feasibility and effects of preventative home visits for at-risk older people: design of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2009; 10.1186/1471-2318-9-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, Allen RES. The meaning of “ageing in place” to older adults. Gerontologist. 2012;52:357–366. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060. Current Population Report, P25–1143, US Census Bureau, Washington DC, 1914.

- 5.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Older people report. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/population-groups/older-people/reports. Accessed 1 July 2019.

- 6.Martins JO, de la Maisonneuve C. The drivers of public expenditure on health and long-term care: an integrated approach. OECD Econ Stud. 2006;42:115–154. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Residential aged care and aged care packages in the community 2012–13. Media release 2014.

- 8.Löfqvist Charlotte, Eriksson Staffan, Svensson Torbjörn, Iwarsson Susanne. First Steps towards Evidence-Based Preventive Home Visits: Experiences Gathered in a Swedish Municipality. Journal of Aging Research. 2012;2012:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/352942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King AI, Parsons M, Robinson E, Jörgensen D. Assessing the impact of a restorative home care service in New Zealand: a cluster randomised trial. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xie C, Hughes J, Sutcliffe C, Chester H, Challis D. Promoting personalization in social care services for older people. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2012;55:218–232. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.639437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corbin CB, Pangrazi RP. Toward a uniform definition of wellness: a commentary. Pres Counc Phys Fit Sports Res Dig. 2001;3(5):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane A, Furlong M, McGilloway S, Molloy DW, Stevenson M, Donnelly M. Time-limited home-care reablement services for maintaining and improving the functional independence of older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016. 10.1002/14651858.CD010825.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Low L-F, Yap M, Brodaty H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011; 10.1186/1472-6963-11-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Aged and Community Services Australia, Case Management Society of Australia. Case Management and Community Care: A Discussion Paper. 2006; Sydney Australia.

- 15.You E, Dunt D, Doyle C. Influences on case-managed community aged care practice. Qual Health Res. 2016;26:1649–1661. doi: 10.1177/1049732315601669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huss A, Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, Egger M, Clough-Gorr KM. Multidimensional preventive home visit programs for community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:298–307. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tourigny A, Bédard A, Laurin D, Kröger E, Durand P, Bonin L, Sévigny A, Frappier A, Roussel ME, Martin M. Preventive home visits for older people: a systematic review. Can J Aging. 2015;34:506–523. doi: 10.1017/S0714980815000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayo-Wilson Evan, Grant Sean, Burton Jennifer, Parsons Amanda, Underhill Kristen, Montgomery Paul. Preventive Home Visits for Mortality, Morbidity, and Institutionalization in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e89257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, Ayis S, Gooberma-Hill R, Horwood J, Ebrahim S. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:725–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher David, Liberati Alessandro, Tetzlaff Jennifer, Altman Douglas G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markle-Reid M, Browne G, Gafni A. Nurse-led health promotion interventions improve quality of life in frail older home care clients: lessons learned from three randomized trials in Ontario, Canada. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19:118–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vass M, Avlund K, Lauridsen J, Hendriksen C. Feasible model for prevention of functional decline in older people: municipality-randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:563–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). [Computer program] Version 5.3. Copenhagen; 2014.

- 24.Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Saarenheimo M, Laakkonen M-L, Pietilä M, Savikko N, Kautiainen H, et al. Family care as collaboration: effectiveness of a multicomponent support program for elderly couples with dementia. Randomized controlled intervention study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2200–2208. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samus QM, Johnston D, Black BS, Hess E, Lyman C, Vavilikolanu A, et al. A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: the maximizing independence at home (MIND) pilot randomized trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:398–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.12.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, Peduzzi PN, Allore H, Byers A. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, elderly persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1068–1074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahoney JE, Shea TA, Przybelski R, Jaros L, Gangnon R, Cech S, Schwalbe A. Kenosha County falls prevention study: a randomized, controlled trial of an intermediate-intensity, community-based multifactorial falls intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:489–498. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Notkola I-L, Hentinen M, Kivela S-L, Sivenius J, Sulkava R. Effects of supporting community-living demented patients and their caregivers: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1282–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phung Kieu T T, Waldorff F B, Buss D V, Eckermann A, Keiding N, Rishøj S, Siersma V, Sørensen J, Søgaard R, Sørensen L V, Vogel A, Waldemar G. A three-year follow-up on the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for patients with mild dementia and their caregivers: the multicentre, rater-blinded, randomised Danish Alzheimer Intervention Study (DAISY) BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003584. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakanishi M, Endo K, Hirooka K, Granvik E, Minthon L, Nägga K, et al. Psychosocial behaviour management programme for home-dwelling people with dementia: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33:495–503. doi: 10.1002/gps.4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spice CL, Morotti W, George S, Dent THS, Rose J, Harris S, et al. The Winchester falls project: a randomised controlled trial of secondary prevention of falls in older people. Age Ageing. 2009;38:33–40. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pardessus V, Puisieux F, Di Popeo C, Gaudefroy C, Thevenon A, Dewailly P. Benefits of home visits for falls and autonomy in the elderly: a randomized trial study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:247–252. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luukinen H, Lehtola S, Jokelainen J, Väänänen-Sainio R, Lotvonen S, Koistinen P. Prevention of disability by exercise among the elderly: a population-based, randomized, controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24:199–205. doi: 10.1080/02813430600958476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammar T, Perälä M-L, Rissanen P. The effects of integrated home care and discharge practice on functional ability and health-related quality of life: a cluster-randomised trial among home care patients. Int J Integr Care. 2007;7:1–12. doi: 10.5334/ijic.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caplan GA, Williams AJ, Daly B, Abraham K. A randomized, controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary intervention after discharge of elderly from the emergency department--the DEED II study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1417–1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland Richard, Lenaghan Elizabeth, Harvey Ian, Smith Richard, Shepstone Lee, Lipp Alistair, Christou Maria, Evans David, Hand Christopher. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7486):293. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38338.674583.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care - the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2007;36:292–297. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, Carver D, MacPherson KM, Beanlands HE, Powell C, et al. A Clinimetric evaluation of specialized geriatric Care for Rural Dwelling, frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1080–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beland F, Bergman H, Lebel P, Dallaire L, Fletcher J, Contandriopoulos A-P, et al. Integrated services for frail elders (SIPA): a trial of a model for Canada. Can J Aging. 2006;25:25–42. doi: 10.1353/cja.2006.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beland F, Bergmann H, Lebel P, Clarfield AM, Tousignant P, Contandriopoulos A-P, et al. A system of integrated care for older persons with disabilities in Canada: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:367–373. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shapiro A, Taylor M. Effects of a community-based early intervention program on the subjective well-being, institutionalization, and mortality of low-income elders. Gerontologist. 2002;42:334–341. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalby DM, Sellors JW, Fraser FD, Fraser C, van Ineveld C, Howard M. Effect of preventive home visits by a nurse on the outcomes of frail elderly people in the community: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2000;162:497–500. doi: 10.1016/S1381-1169(00)00419-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senior HEJ, Parsons M, Kerse N, Chen M-H, Jacobs S, van der Hoorn S. Promoting independence in frail older people: a randomised controlled trial of a restorative care service in New Zealand. Age Ageing. 2014;43:418–424. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]