Abstract

Nonhuman primates, and great apes in particular, possess a variety of cognitive abilities thought to underlie human brain and cognitive evolution, most notably, the manufacture and use of tools. In a relatively large sample (N = 226) of captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) for whom pedigrees are well known, the overarching aim of the current study was to investigate the source of heritable variation in brain structure underlying tool use skills. Specifically, using source-based morphometry (SBM), a multivariate analysis of naturally occurring patterns of covariation in gray matter across the brain, we investigated (1) the genetic contributions to variation in SBM components, (2) sex and age effects for each component, and (3) phenotypic and genetic associations between SBM components and tool use skill. Results revealed important sex- and age-related differences across largely heritable SBM components and associations between structural covariation and tool use skill. Further, shared genetic mechanisms appear to account for a heritable link between variation in both the capacity to use tools and variation in morphology of the superior limb of the superior temporal sulcus and adjacent parietal cortex. Findings represent the first evidence of heritability of structural covariation in gray matter among nonhuman primates.

Keywords: chimpanzee, gray matter covariation, heritability, source-based morphometry, tool use

Primates, in general, and great apes specifically have been particularly important species in comparative neuroscience studies because of their phylogenetic similarity to humans. Furthermore, compared with more distantly related primate species, great apes display a variety of behavioral and cognitive abilities that are thought to underlie human brain and cognitive evolution, such as rudimentary linguistic skills, delay of gratification, complex social cognition, and with specific reference to this study, the manufacture and use of tools (Savage-Rumbaugh 1986; Savage-Rumbaugh and Lewin 1994; de Waal 1996; Shumaker et al. 2011; Vaesen 2012; Beran 2015). Indeed, save humans, the complexity and scope of tool manufacture and use in chimpanzees are unmatched among primates. For instance, a variety of forms of tool manufacture and use have been described across different geographical regions of Africa as well as in different captive settings (Whiten et al. 1999, 2001; Shumaker et al. 2011). Within communities of wild chimpanzees, there is evidence of intergenerational transmission of local forms of tool use expression suggesting that social learning plays an important role in the acquisition and maintenance of these specific traditions. Thus, the manufacture and use of tools in chimpanzees is highly adaptive skill and was likely strongly selected for in human evolution after the split from the last common ancestor with chimpanzees.

Despite the significance of tool manufacture and use in primate evolution, there are relatively few studies on their genetic and neural basis in nonhuman primates, and particularly chimpanzees. In humans, meta-analyses of functional brain imaging data have identified a set of connected regions within the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices, particularly in the left hemisphere, that are implicated in planned tool use actions (Johnson-Frey 2004; Frey et al. 2005). There is also evidence that lesions to regions within this circuit can result in deficits in the representation and execution of planned motor actions, including language and speech (Goldenberg and Randerath 2015; Weiss et al. 2015). Studies in captive chimpanzees have previously found that variation in skill and hand use are linked to variation in gray matter volume and asymmetry, particularly within premotor, parietal, and primary motor cortices, as well as the cerebellum (Hopkins et al. 2007, 2017; Cantalupo et al. 2008; Gilissen and Hopkins 2013).

Here, instead of using an a priori region-of-interest approach and method, we assessed phenotypic associations in tool use skill with structural covariation in gray matter measured from magnetic resonance images (MRIs). Specifically, we used source-based morphometry (SBM), a relatively new method used to characterize gray matter structural covariation in a sample of MRI scans of chimpanzees (Alexander-Bloch et al. 2013; Bard and Hopkins 2018). Unlike univariate analytic methods, such as voxel-based morphometry (VBM), SBM is a multivariate, data-driven analytic approach that utilizes information about relationships among voxels to group voxels carrying similar information across the brain. Without requiring prior determination of regions of interest, the resulting components or sources are identified based on the spatial information between voxels grouped in a natural manner and represent similar covariation networks between subjects; thus, this approach has been described as a multivariate version of VBM (Xu et al. 2009). Previous studies in humans have identified roughly 30 distinct gray matter sources that encompass a variety of different cortical regions that are presumably involved in different behavioral and cognitive functions and may be disrupted in certain clinical populations (Xu et al. 2009; Kasparek et al. 2010; Caprihan et al. 2011; Rektorova et al. 2014; Grecucci et al. 2016).

Based on the components derived from the SBM analysis, we subsequently correlated individual variation in the weighted scores for each subject and component with a measure of tool use skill previously measured in the chimpanzees (Hopkins et al. 2009). Of specific interest was whether performance measures of tool use skill were associated with source-based component scores that reflected structural covariation in gray matter in regions within the frontal, parietal, and temporal cortices.

In addition, we also tested for genetic associations between individual differences in gray matter structural covariation and tool use skill in the chimpanzee sample using quantitative genetic analyses. Notably, following methods we and others have previously used in humans (Eyler et al. 2012; Jansen et al. 2015; Strike et al. 2015), chimpanzees, and other nonhuman primates (Rogers et al. 2007; Fears et al. 2009; Kochunov et al. 2010; Fears et al. 2011; Gomez-Robles et al. 2015; Gomez-Robles et al. 2016), we initially estimated heritability for (1) each component derived from the SBM analysis and (2) tool use performance measures (Hopkins et al. 2015). For those SBM components that showed significantly heritability and phenotypically correlated with tool use performance, we then performed genetic correlations to test whether common genes underlie their expression (i.e., pleiotropy). Evidence of significant genetic association would suggest that potentially common genes underlie individual variation in both tool use skill and gray matter structural covariation.

Materials and Method

Subjects

This study includes data from 226 captive chimpanzees (136 females, 85 males), comprising 88 chimpanzees housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center (YNPRC) and 138 chimpanzees housed at the National Center for Chimpanzee Care (NCCC). Ages at the time of their in vivo MRI scans ranged from 8 to 53 years (Mean = 27.04, SD = 6.74). Of the 226 chimpanzees for which MRI scans were obtained, measures of tool use skill were available for 204 individuals, including 123 females and 81 males. Of these 204 apes, 134 were housed at NCCC and 70 at the YNPRC. These subjects were included in all analyses pertaining to phenotypic associations between tool use skill and the SBM components. All tool use data were collected within 3 years of the acquisition of the MRI scans. We note here that the NCCC and YNPRC are genetically isolated populations of captive chimpanzees. That is to say, these populations were created from separate founder chimpanzees and there was no interbreeding between chimpanzees living in these 2 facilities. We took advantage of this opportunity to evaluate consistency and reproducibility in the estimates of heritability in SBM components and their association with tool use skill measures in our analyses (see Baker 2016).

Tool Use Skill

The apparatus and procedure used to quantify tool use skill, as well as heritability, have been described in detail elsewhere (Hopkins et al. 2009, 2015). Briefly, to assess tool use skill, we recorded the latency to insert a small stick into a hole to extract food, averaged across a total of 50 trials in each chimpanzee. The average latency scores were converted to standardized z-scores within the NCCC and YNPRC to account for differences in the duration of experience that chimpanzees at each colony had with the tool use device. In previously published studies (Hopkins et al. 2015), we found average tool latency to be significantly heritable (h2 = 0.395, s.e. = 0.129, P < 0.001) and this was the case for chimpanzees at both the NCCC (h2 = 0.356, s.e. = 0.155, P < 0.007) and YNPRC (h2 = 0.463, s.e. = 0.190, P < 0.007) when analyzed separately.

MRI Collection

All chimpanzees were scanned during one of their annual physical examinations. MRI scans followed standard procedures at the YNPRC and NCCC and were designed to minimize stress. Thus, the animals were first sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg) or telazol (3–5 mg/kg) and were subsequently anesthetized with propofol (40–60 mg/(kg/h)). They were then transported to the MRI scanning facility and placed in a supine position in the scanner with their head in a human head coil. Upon completion of the MRI, chimpanzees were briefly singly housed for 2–24 h to permit close monitoring and safe recovery from the anesthesia prior to return to the home social group. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at YNPRC and NCCC and also followed the guidelines of the Institute of Medicine on the use of chimpanzees in research. Seventy-seven chimpanzees (all from YNPRC) were scanned using a 3.0-T scanner (Siemens Trio, Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc.). T1-weighted images were collected using a 3D gradient echo sequence (pulse repetition = 2300 ms, echo time = 4.4 ms, number of signals averaged = 3, matrix size = 320 × 320, with 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 resolution). The remaining 149 chimpanzees (11 from YNPRC, 138 from NCCC) were scanned using a 1.5 T G.E. echo-speed Horizon LX MR scanner (GE Medical Systems). T1-weighted images were collected in the transverse plane using a gradient echo protocol (pulse repetition = 19.0 ms, echo time = 8.5 ms, number of signals averaged = 8, matrix size = 256 × 256, with 0.7 × 0.7 × 1.2 resolution).

Image Processing and SBM Analysis

All T1-weighted MRI scans were realigned in the AC-PC plane and skull-stripped using the BET function in FSL (Zhang et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2004) and resampled at 0.7-mm isotropic voxels. Following this initial preprocessing step, the images were analyzed following the steps used for voxel-based morphometry analyses using FSL (Analysis Group, FMRIB) (Smith et al. 2004). Specifically, images were registered to a chimpanzee template brain, then segmented into gray and white matters as well as CSF. Subsequently, a study-specific gray matter template brain was created and each subject’s segmented scan was nonlinearly registered to the template brain and the Jacobian warping matrix was saved for each subject. The gray matter intensity values were then multiplied by the Jacobian warp to estimate the modulated gray matter volume within each voxel.

For the SBM, the individual modulated gray matter volumes were analyzed using the software program Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT) (http://mialab.mrn.org/software/gift/index.html). In SBM, the images are concatenated into a 2D array or matrix with the number of subjects and voxels as the matrix. Subsequently, principal component analysis (PCA) is performed on the matrix to reduce dimensionality using the Minimum Description Length algorithm, which was estimated to be 24 for the combined chimpanzee sample. Consistent with other SBM studies in humans (Xu et al. 2009; Grecucci et al. 2016), the data were then subjected to spatial PCA using the Infomax algorithm, which produces a source and mixing matrix. The source matrix is a subject X PCA array with each value presenting the relative contributions of each subject’s data to the composition of each PCA. The source matrix values were the primary dependent measure of interest. To visualize the component structures, we used the mixing matrix which is a 3D volume that depicts the characteristics of the spatial characteristics and covariation in gray matter for each PCA. Values within the mixing matrices are represented as standardized scores and can therefore take on both negative and positive values. Consistent with previous studies, we thresholded each PCA component at an absolute value of 3.00 and included only those clusters that survived this threshold as significant.

Heritability Analyses

From the SBM analysis, one outcome measure is the individual subject’s weighted score in deriving each independent component. Much like in factor or PCA, each subject’s weighted score can vary on a continuous scale from negative to positive with the absolute indicating the magnitude of their score. To estimate heritability in our chimpanzee sample, the outcome measures for all identified SBM components were subjected to a quantitative genetic analysis to estimate heritability using the software program SOLAR (Almasy and Blangero 1998). SOLAR uses a variance components approach to estimate the polygenic component of variance when considering the entire pedigree (see Rogers et al. 2007; Fears et al. 2009; Fears et al. 2011; Hopkins 2013; Hopkins, Keebaugh, et al. 2014; Hopkins, Russell, et al. 2014). We used SOLAR in 2 ways in this study. First, we used it to estimate and statistically determine whether the weighted component scores were significantly heritable in the entire chimpanzee sample as well as within each population to assess the reproducibility. Second, we used SOLAR to calculate genetic correlations between the tool use performance data and the SBM component scores. Covariates included sex, age, scanner magnet, and rearing history of the subjects (i.e., wild-caught, mother-reared, or human-reared).

Results

Descriptive SBM Results

From the SBM analysis, there were 24 components identified that were distributed throughout the cortex and cerebellum. An anatomical description of the 24 components and their volumes are provided in Table 1. 3D renderings of each component are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 1.

Anatomical description and volume of each SBM component

| Component | Volume |

|---|---|

| Component 1 | |

| Precuneus (L), precentral gyrus (L), medulla oblongata | 4264.18 |

| Component 2 | |

| Lateral cerebellar hemispheres (inferior), bilateral | 8019.00 |

| Component 3 | |

| Superior parietal cortex, bilateral | 6313.60 |

| Component 4 | |

| Anterior cingulate cortex (R), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (R), supplemental motor area (R) | 5621.77 |

| Component 5 | |

| Primary visual cortex (L) | 7319.62 |

| Component 6 | |

| Frontopolar cortex (B) | 9232.19 |

| Component 7 | |

| Primary motor and premotor cortex (dorsal) (B) | 8512.57 |

| Component 8 | |

| Cuneus (L), lateral cerebellar hemisphere (R) | 5761.37 |

| Component 9 | |

| Cuneus (B), hippocampal formation (R) | 5140.88 |

| Component 10 | |

| Lateral cerebellar hemispheres (B) | 7903.75 |

| Component 11 | |

| Anterior cingulate cortex (B), frontopolar cortex (B), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (B) | 9430.10 |

| Component 12 | |

| Primary visual cortex (R) | 5181.70 |

| Component 13 | |

| Primary visual cortex (B), cuneus (B) | 9880.11 |

| Component 14 | |

| Anterior temporal cortex (B), anterior insular cortex (B), inferior temporal cortex (R) | 4870.26 |

| Component 15 | |

| Anterior temporal cortex (B) | 9169.76 |

| Component 16 | |

| Basal forebrain (B) | 5470.51 |

| Component 17 | |

| Primary motor and somatosensory cortex (dorsal) (B) | 8646.34 |

| Component 18 | |

| Lateral cerebellar hemispheres (B) | 10 408.68 |

| Component 19 | |

| Frontopolar cortex (B) | 5212.23 |

| Component 20 | |

| Lateral cerebellar hemispheres (B) | 8719.75 |

| Component 21 | |

| Cerebellar vermis (B) | 9140.95 |

| Component 22 | |

| Primary visual cortex (B) | 9248.31 |

| Component 23 | |

| Cerebellar vermis and medial hemisphere (B) | 8076.21 |

| Component 24 | |

| Superior parietal cortex (B) | 8040.95 |

Note: Volumes are in mm3. (R) = right hemisphere, (L) = left hemisphere, (B) = bilateral.

Heritability of SBM Component Scores

For the SOLAR analyses, we estimated the heritability for the standardized SBM z-scores for each component. Age, sex, rearing history, and scanner magnet served as covariates in these analyses. The proportion of variability attributed to genetic factors and the covariates are shown in Table 2. Significant heritability estimates were found for 18 of the 24 components with significant h2 values ranging from 0.246 to 0.886, suggesting moderate to strong effects. Significant covariate effects of scanner magnet were found for 20 components which was not surprising given that the gray and white matter contrast is influenced by the scanner magnet. Age accounted for a significant proportion of variance in components 8, 11, 14, 19, and 21, respectively. Sex accounted for a significant proportion of variance in components 10, 12, 13, 15 19, and 23, while the rearing history variable was not significant for any components.

Table 2.

Heritability and covariate effects for each SBM component

| Component | h 2 | s.e. | P | Covariates | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.378 | 0.156 | 0.004 | Scanner | 0.290 |

| 2 | 0.886 | 0.115 | 0.0000001 | Scanner | 0.127 |

| 3 | 0.854 | 0.101 | 0.0000001 | None | |

| 4 | 0.314 | 0.132 | 0.003 | Scanner | 0.218 |

| 5 | 0.341 | 0.162 | 0.01 | Scanner | 0.131 |

| 6 | 0.216 | 0.112 | 0.065 | None | |

| 7 | 0.184 | 0.161 | 0.107 | Scanner | 0.395 |

| 8 | 0.260 | 0.141 | 0.025 | Age | 0.035 |

| 9 | 0.374 | 0.126 | 0.0007 | Scanner | 0.197 |

| 10 | 0.497 | 0.171 | 0.001 | Scanner, sex | 0.252 |

| 11 | 0.658 | 0.171 | 0.0003 | Scanner, age | 0.189 |

| 12 | 0.366 | 0.159 | 0.006 | Scanner, sex | 0.103 |

| 13 | 0.565 | 0.157 | 0.0003 | Scanner, sex | 0.433 |

| 14 | 0.304 | 0.153 | 0.016 | Scanner, age | 0.151 |

| 15 | 0.146 | 0.147 | 0.139 | Scanner, sex | 0.215 |

| 16 | 0.038 | 0.111 | 0.363 | Scanner | 0.292 |

| 17 | 0.465 | 0.137 | 0.00001 | Scanner | 0.305 |

| 18 | 0.154 | 0.148 | 0.127 | None | |

| 19 | 0.531 | 0.149 | 0.00005 | Scanner, sex, age | 0.252 |

| 20 | 0.830 | 0.121 | 0.0000001 | Scanner | 0.076 |

| 21 | 0.579 | 0.166 | 0.00003 | Scanner, age | 0.008 |

| 22 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.5000 | Scanner | 0.034 |

| 23 | 0.246 | 0.153 | 0.039 | Scanner, sex | 0.136 |

| 24 | 0.252 | 0.129 | 0.014 | Scanner | 0.219 |

Note: h2 = heritability coefficient, s.e. = standard error. Covariates indicate those variables that accounted for a significant proportion of variance in the SBM scores and proportion of variance accounted for them. Bolded values are those heritability estimates that are significant at P < .05.

Sex and Age Covariate Effects

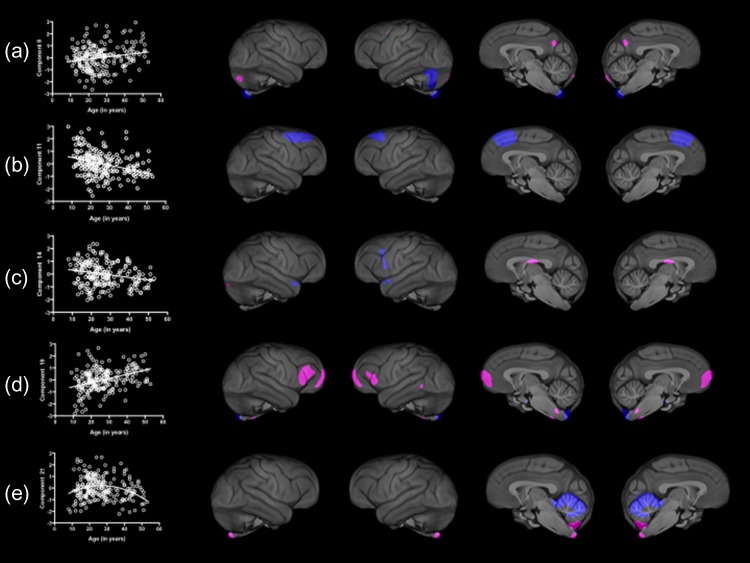

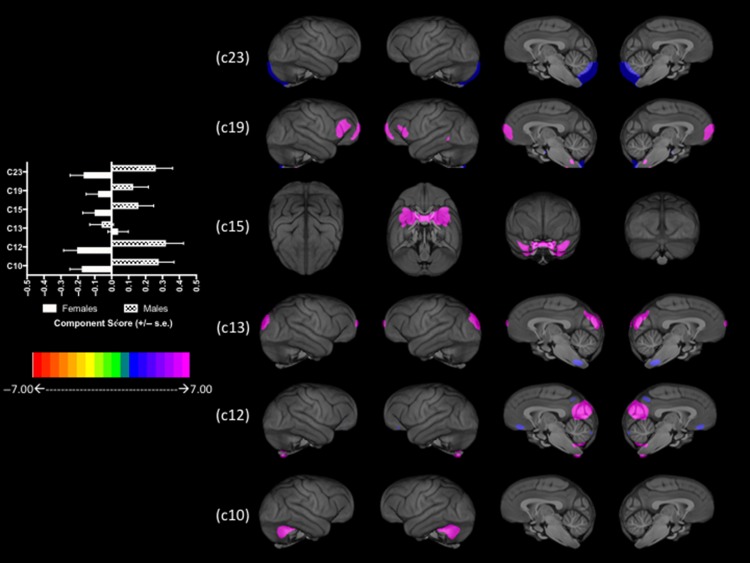

To further evaluate the contributions of the factors sex and age, we performed several follow-up analyses. For the SBM components in which age was a significant effect, we fit polynomial lines between age and weighted scores for components 8, 11, 14, 19, and 21 using stepwise multiple regression. The outcome measures were the component scores, while the predictor variables were sex, scanner strength, the linear age, then curvilinear age variables. We calculated the significance in change in R2 to determine which age distribution best explained the variability in the SBM component score. The scatterplots between age and the SBM-weighted scores, as well as the best fit line are shown in Figure 1a–e. For component 8, the overall model was significant; R = 0.239 F(4, 219) = 3.313, P = 0.012. Significant changes in R2 (0.170 to 0.235) were found for the linear; F(1, 220) = 6.179, P = 0.012 but not the curvilinear (0.235 to 0.239); F(1, 219) = 0.379, P = 0.539 age variable. Component 8 is comprised of the right cerebellum and left cuneus and the association was positive with older individuals having higher values compared with younger individuals. For component 11, the overall model was significant; R = 0.487 F(4, 219) = 17.012, P = 0.001. Significant changes in R2 (0.149 to 0.219) were found for the linear; F(1, 220) = 20.876, P = 0.001, but not the curvilinear (0.219 to 0.223); F(1, 219) = 2.153, P = 0.144 age variable. Component 11 included the dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, frontopolar and anterior cingulate cortex, and the associations were negative with older individuals having lower values compared with younger apes. For component 14, the overall model was significant; R = 0.405 F(4, 219) = 10.751, P = 0.001. Significant changes in R2 (0.373 to 0.402) were found for the linear; F(1, 220) = 5.656, P = 0.018, but not the curvilinear (0.401 to 0.405); F(1, 219) = 0.825, P = 0.365 age variable. Component 14 was comprised of the anterior temporal, inferior temporal, and anterior insular cortices. The linear association was negative, suggesting that older subjects have lower values. For component 19, the overall model was significant; R = 0.543 F(4, 219) = 22.885, P= 0.001. Significant changes in R2 (0.439 to 0.541) were found for the linear; F(1, 220) = 31.043, P = 0.001 but not the and curvilinear (0.541–0.543); F(1, 219) = 0.724, P = 0.396 age variables. Component 19 was comprised of frontopolar cortex, and older chimpanzees had relatively higher weighted scores compared to middle-aged and younger individuals. Finally, for component 21, the overall model was significant; R = 0.255 F(4, 219) = 3.803, P = 0.005. Significant changes in R2 (0.148 to 0.197) were found for the linear; F(1, 220) = 3.824, P = 0.052 and the curvilinear (0.197–0.255); F(1, 219) = 6.153, P = 0.014 age variables. Component 21 was comprised of vermis of the cerebellum. Older and younger chimpanzees had relatively lower weighted scores compared to middle-aged individuals. The mean weighted z-scores for components 10, 12, 13, 15 19, and 23 in male and female chimpanzees are shown in Figure 2. Males had significantly higher weighted scores compared with females on all components with the exception of 13 (see Table 1 for descriptions of the regions).

Figure 1.

Scatterplots showing significant associations between age and SBM components (a) 8, (b) 11, (c) 14, (d) 19, and (e) 21. Left panel shows the scatterplot between age and the weighted SBM component scores and the right panel shows regions comprising each component.

Figure 2.

Left panel: Mean SBM-weighted scores for males and females for components 10, 12, 13, 15 19, and 23. Right panel: Brain regions comprising each component.

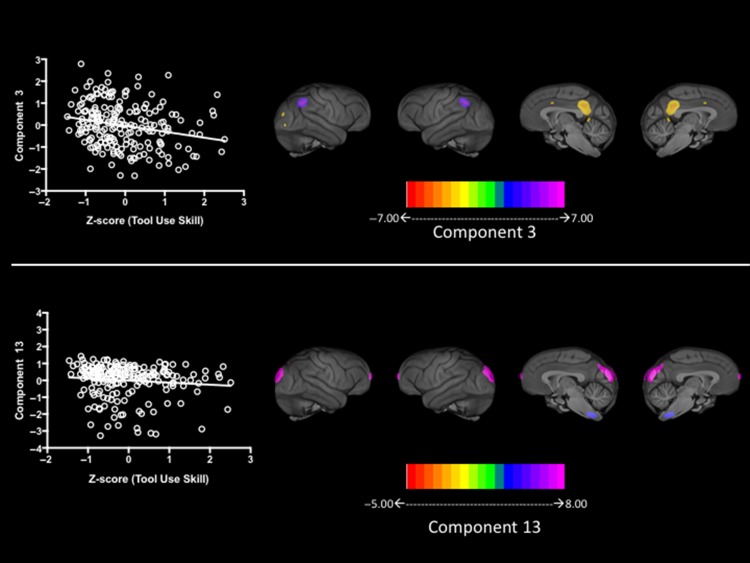

Phenotypic and Genetic Associations between Tool Use Skill and SBM Components

For this analysis, we used partial correlation coefficients between the standardized z-scores of the tool use latency measures and each SBM component while statistically controlling for sex, scanner magnet, rearing history, and age of the subjects. Three subjects (all females) were removed from this analysis because they were identified as outliers on their tool use performance measure based on boxplots of the standardized z-scores. Significant positive associations were found between tool use latency scores and 2 SBM regions, including components 3 (r = −0.211, P = 0.003) and 13 (r = −0.168, P = 0.019) (see Fig. 3). Component 3 consisted of the posterior superior temporal sulcus (STS) and superior parietal cortex, while component 13 was comprised of primary visual cortex and cuneus. The associations were negative, thus subjects with slower average latency scores contributed less to the component scores within each these regions. Finally, we calculated genetic correlations between the tool use skill measures and each of the SBM components (see Table 3). Significant and large genetic correlations were found between tool use skill and components 3 (rhog = 0.519, P = 0.03) and 13 (rhog = 0.717, P = 0.02).

Figure 3.

Upper and lower left panel = scatterplot between tool use performance measures and weighted scores for SBM components 3 (left) and 13 (right). Upper and lower bottom panel shows brain regions in SBM components 3 and 13.

Table 3.

Phenotypic correlations between tool use skill and SBM component scores for the entire sample and within the NCCC and YNPRC chimpanzee colonies

| Overall | NCCC | YNPRC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | +0.018 | +0.103 | −0.125 |

| 2 | −0.035 | −0.046 | −0.030 |

| 3 | −0.211 | −0.202 | −0.248 |

| 4 | +0.057 | +0.106 | −0.021 |

| 5 | +0.026 | −0.023 | +0.187 |

| 6 | −0.053 | −0.104 | −0.010 |

| 7 | −0.111 | −0.061 | −0.213 |

| 8 | −0.110 | −0.127 | −0.079 |

| 9 | −0.058 | +0.004 | −0.165 |

| 10 | −0.055 | −0.041 | −0.068 |

| 11 | +0.028 | +0.104 | −0.115 |

| 12 | −0.017 | −0.027 | −0.032 |

| 13 | −0.168 | −0.296 | −0.150 |

| 14 | +0.031 | +0.065 | −0.052 |

| 15 | −0.030 | +0.057 | −0.053 |

| 16 | +0.078 | −0.003 | −0.180 |

| 17 | +0.126 | +0.091 | +0.190 |

| 18 | +0.079 | +0.146 | −0.141 |

| 19 | −0.002 | −0.017 | +0.028 |

| 20 | +0.030 | −0.005 | +0.110 |

| 21 | +0.075 | +0.100 | +0.033 |

| 22 | +0.008 | −0.038 | +0.194 |

| 23 | +0.022 | +0.015 | +0.067 |

| 24 | −0.027 | −0.017 | −0.069 |

Note: Bolded values are significant at P < 0.05.

Reproducibility Between Chimpanzee Populations

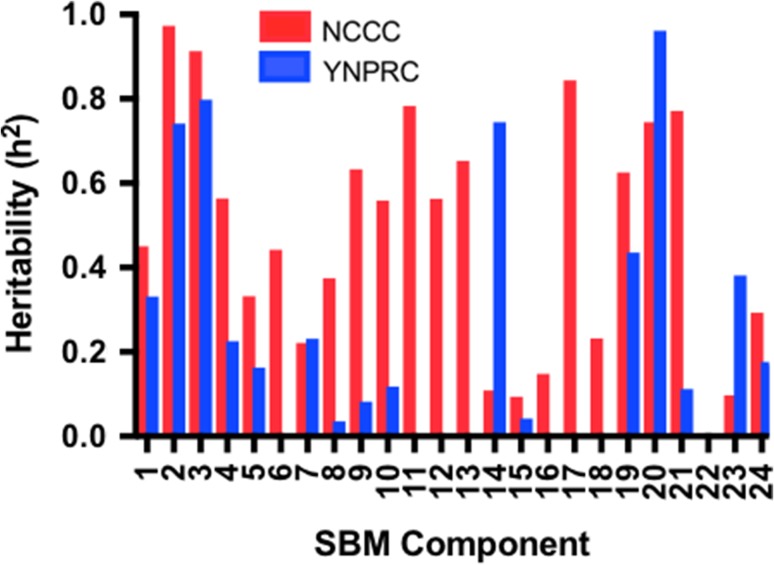

Recall that we tested 2 colonies of genetically unrelated chimpanzees that were scanned on different platforms. Thus, to assess the consistency in results between the 2 colonies, we performed several additional analyses. First, we performed separate heritability analyses in the NCCC (n = 138) and YNPRC (N = 88) chimpanzees for each SBM component derived from the entire sample (see Fig. 4). Within the NCCC samples, 17 of the 24 components were significantly heritable compared with only 7 within the YNPRC sample. Further, the average heritability across all 24 components was significantly higher in the NCCC (h2 = 0.575) compared with YNPRC (h2 = 0.233) sample t(23) = 3.434, P = 0.002. Ten of the 24 SBM components showed consistently significant or nonsignificant heritability in both the NCCC and YNPRC samples (Components 1, 2, 3, 4, 15, 16, 19, 20, 22, and 24, respectively). In addition, we assessed the phenotypic correlations between the tool use performance measures and the SBM components' scores within the NCCC and YNPRC samples. These data are shown in Table 3. As can be seen, for component 3 significant negative associations were found between tool use skill and the SBM-weighted component scores for the entire sample as well as within both the NCCC and YNPRC samples. A similar pattern was observed for component 13, although the YNPRC did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (P < 0.05). Indeed, although the estimate did not reach the P < 0.05 level of significance, the magnitude of the correlation within the YNPRC sample (−0.150) was very similar to the significant (P < 0.05) association in the full combined sample (−0.168).

Figure 4.

Heritability for each SBM component in the NCCC (red) and YNPRC (blue) chimpanzee populations.

Discussion

There were 5 main findings in this study. First, we found 24 gray matter SBM components in chimpanzees. Second, gray matter structural covariation was influenced by sex and age. Third, a majority of the SBM components were significantly heritable, suggesting that genetic factors may influence their expression across subjects. Fourth, heritability of the SBM components were modestly consistent between 2 genetically isolated populations of captive chimpanzees. Finally, we found significant phenotypic and genetic correlations between tool use skill and 2 SBM components. These latter findings have several important implications for primate brain evolution and the emergence of tool manufacture and use.

With respect to the 24 component revealed by the SBM analysis, this is fewer than the number reported in at least some previous reports in human brains (Xu et al. 2009). The differing numbers of components may reflect inherent differences in the covariation of gray matter between humans and chimpanzees; however, we cannot rule out that the potential differences in SBM organization between humans and chimpanzees may be a result of different sample size, scanner parameters, voxel resolution, or other methodological factors. Notwithstanding, many of the components identified in our chimpanzee sample have been similarly described in human SBM analyses (Grecucci et al. 2016).

Second, gray matter structural covariation in the chimpanzee brain was influenced by age and sex. Males and females differed significantly on 6 of the 24 components and these differences presumably underlie behavioral, affective, motor, or cognitive functions that distinguish the 2 sexes. Certainly male and female chimpanzees differ with respect to social behavior, such as aggression and grooming partners, as well as in their role within the community where, for example, males typically patrol the home range and females do not (Goodall 1986; Boesch and Boesch-Achermann 2000; Mitani and Watts 2005; Lehmann and Boesch 2008). Further, there is some evidence of sex differences in learning, hand use, and performance on tool use tasks in chimpanzees (Pandolfi et al. 2003; Lonsdorf et al. 2004; Gruber et al. 2010; Bogart et al. 2012; Sanz et al. 2016). While it is tempting to speculate that the observed sex-dependent gray matter covariation differences reported here underlie male–female behavioral differences, we have no direct evidence to support this assertion. This will require additional studies beyond the scope of this report.

Age significantly and linearly correlated with 4 components and showed a significant quadratic association for one component. For components 8 and 19, we found positive associations between age and the weighted scores, suggesting that older individuals are contributing more to the generation of these components than younger individuals. These 2 sources largely comprised prefrontal, premotor, and portion of the cerebellum, and the most parsimonious explanation is that maturational factors contribute to the increased covariation in gray matter density within these regions (Terribilli et al. 2011; Lemaitre et al. 2012). Age was negatively correlated with components 11 and 14 which included superior frontal, supplementary motor and anterior temporal cortex suggesting a reduction in covariation with increasing age. The associations between age and component 21 is slightly more difficult to interpret because it exhibited curvilinear relationship. Older and younger chimpanzees had relatively lower weighted scores than middle-aged apes for this component, which was comprised entirely of the cerebellum.

It is worth noting that, within the larger context of studies on age-related changes in the great ape brain (Gearing et al. 1994, 1997; Rosen et al. 2008; Perez et al. 2013; Edler et al. 2017), the results reported here are somewhat novel. For instance, Sherwood et al. (2011) failed to find any significant age-related changes in overall gray and white matter volume in a sample of 99 chimpanzees. More recently, Autrey et al. (2014), in a sample of 219 chimpanzee MRI scans, reported that chimpanzees show (1) increasing gyrification with age, (2) a cubic association between age and white matter volume, and (3) a negative association between age and the depth and width of the fronto-orbital sulcus. Recall that here, we found significant linear and quadratic associations between gray matter covariation and age, a finding not previously reported in the chimpanzee brain at least with respect to gray matter variation.

Regarding heritability, there are some reports of the genetic contributions to individual differences in cortical organization in nonhuman primates, including chimpanzees (Rogers et al. 2007, 2010; Fears et al. 2009; Kochunov et al. 2010). For instance, Gomez-Robles et al. (2015) have previously reported modest heritability of cortical shape and for different linear measures of sulci in chimpanzees. Our findings similarly reveal moderate heritability in most (18 of the 24 components, see Table 2), but not all structurally covarying gray matter regions in the chimpanzee brain. We also found modest consistency in heritability between the NCCC and YNPRC chimpanzee populations. Ten of the 24 components showed consistent heritability (or lack thereof) between the 2 populations. One limitation in our effort to replicate the heritability results between the 2 chimpanzee populations were (1) differences in the sample sizes, (2) variation in the scanner platform and magnet strength, and (3) the composition of the number of differentially reared chimpanzees. There were 138 NCCC chimpanzees and 88 YNPRC and all the NCCC chimpanzees were scanned on a 1.5-T machine, while 77 of the YNPRC apes were scanned on a 3-T machine and remaining on a 1.5-T magnet. Additionally, the proportion of nursery-reared chimpanzees was higher in the YNPRC compared to NCCC chimpanzees. Previous studies have shown that differences in early rearing can influence gray matter structural covariation in chimpanzees (Bard and Hopkins 2018) and therefore these experiences may have altered the genetic basis of development as manifest by reduced heritability.

Finally, we found that individual variation in tool use motor skill was associated with structural covariation in 2 SBM components that were largely comprised of superior temporal, parietal, and cerebellar cortices. The phenotypic associations between tool use performance and components 3 and 13 were consistent and significant within each chimpanzee population. Further, we found significant genetic correlations between tool use skill and components 3 and 13, which include areas within the posterior STS, posterior cingulate, visual cortex, and the brainstem, suggesting that common genetic mechanisms may underlie their expression.

As noted above, component 3 is comprised of the cuneus and the superior portion of the STS that projects dorsally into the parietal lobe, while component 13 includes occipital regions. Clinical and functional neuroimaging studies in humans have clearly implicated portions of the parietal lobe as playing an important role in providing visual feedback during planned visuomotor actions, such as grasping an object or in the use of tools (Johnson-Frey 2004; Stout and Chaminade 2012; Gilissen and Hopkins 2013; Caminiti et al. 2015; Bruner and Iriki 2016). Furthermore, some have suggested that expansion of the parietal lobe and cuneus was associated with the emergence of increasing complex motor, cognitive and linguistic functions during primate brain evolution (Gannon et al. 2005; LeRoy et al. 2015; Bruner and Iriki 2016; Bruner et al. 2017). Our results suggest that these as yet unknown genetic mechanisms, may account for a heritable link between variation in the capacity to use tools and variation in the morphology of the inferior and superior parietal lobe. Such heritable covariation is a key for natural selection as an explanation for the coevolution of tool skill and cortical structure in humans and apes. Indeed, our results suggest that increased selection for tool use skill may have resulted selective changes in the size, connectivity, or organization of the parietal cortex in humans after that split form the last common ancestor.

In summary, the findings reported here are the first evidence of heritability in structural covariation in gray matter among nonhuman primates. Though this study focused on associations between tool use skill and gray matter structural covariation, future studies should expand this analytic approach to additional behavioral and cognitive phenotypes. This approach could potentially identify brain regions in chimpanzees that exhibit heritable variation associated with particular behavioral or cognitive abilities, providing insight into neuroanatomical targets that could have been selected for expansion in hominins after the split from a last common ancestor. Additionally, this approach could be used to identify key brain regions as foci for subsequent gene expression analyses that could lead to the discovery of candidate genes linked to typical and atypical praxic functions.

Supplementary Material

Notes

The authors would like to thank Yerkes National Primate Research Center and the National Center for Chimpanzee Care and their respective veterinary and care staffs for assistance in collection of the MRI scans. American Psychological Association and Institute of Medicine guidelines for the treatment of animals were followed during all aspects of this study. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Funding

NIH grants 5R01NS042867, 5R01NS073134, and 5P01HD060563, NSF INSPIRE grant SMA-1542848, Cooperative Agreement U42OD011197 to MD Anderson Cancer Center, and to YNPRC, which is currently supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs/OD P51OD11132. MRIs used in this study are a part of the National Chimpanzee Brain Resource (supported by NIH 5R24NS092988).

References

- Alexander-Bloch A, Giedd JN, Bullmore E. 2013. Imaging structrual co-variance between human brain regions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 14:322–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasy L, Blangero J. 1998. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 62:1198–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autrey MM, Reame LA, Mareno MC, Sherwood CC, Herndon JG, Preuss TM, Schapiro SJ, Hopkins WD. 2014. Age-related effects in the neocortical organization of chimpanzees: gray and white matter volume, cortical thickness, and gyrification. Neuroimage. 101:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker M. 2016. Is there a reproducibilty crisis? Nature. 533:452–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard KA, Hopkins WD. 2018. Early socioemotional intervention mediates long-term effects of atypical rearing on structural covariation in gray matter in adult chimpanzees. Psychol Sci. 29:594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beran MJ. 2015. Chimpanzee cognitive control. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 24:352–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesch C, Boesch-Achermann H. 2000. The chimpanzees of the Tai forest: behavioural ecology and evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bogart SL, Pruetz JD, Ormiston LK, Russell JL, Meguerditchian A, Hopkins WD. 2012. Termite fishing laterality in the Fongoli savanna chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus): further evidence of a left hand preference. Am J Phys Anthropol. 149:591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner E, Iriki A. 2016. Extending mind, visuospatial integration, and the evolution of the parietal lobes in the human genus. Quat Int. 405:98–110. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner E, Preuss TM, Chen X, Rilling JK. 2017. Evidence for expansion of the precuneus in human evolution. Brain Struct Funct. 222:1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminiti R, Innocenti GM, Battaglia-Mayer A. 2015. Organization and evolution of parieto-frontal processing streams in macaque monkeys and humans. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 56:73–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantalupo C, Freeman HD, Rodes W, Hopkins WD. 2008. Handedness for tool use correlates with cerebellar asymmetries in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Behav Neurosci. 122:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprihan A, Abbott C, Yamamoto J, Pearlson G, Permone-Bizzozero N, Sui J, Calhoun VD. 2011. Source-based morphometry analysis of group differences in fractional anisotropy in Schizophrenia. Brain Connect. 1:133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM. 1996. GOOD NATURED: the origins of right and wrong in humans and other animals. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Edler MK, Sherwood CC, Meindl RS, Hopkins WD, Ely JJ, Erwin JM, Mufson EJ, Hof PR, Raghanti MA. 2017. Aged chimpanzees exhibit pathologic hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 59:107–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler LT, Chen CH, Panizzon MS, Fennema-Notestine C, Neale MC, Jak A, Jernigan TL, Fischl B, Fraanz CE, Lyons MJ, et al. 2012. A comparion of heritabilty maps of cortical surface area and thickness and the influence of adjustment for whole brain measures: a magnetic resonance imaging study twin study. Twin Res Hum Genet. 15:304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears SC, Melega WP, Service SK, Lee C, Chen K, Tu Z, Jorgensen MJ, Fairbanks LA, Cantor RM, Freimer NB, et al. 2009. Identifying heritable brain phenotypes in an extended pedigree of vervet monkeys. J Neurosci. 29:2867–2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears SC, Scheibel K, Abaryan Z, Lee C, Service SK, Jorgensen MJ, Fairbanks LA, Cantor RM, Freimer NB, Woods RP. 2011. Anatomic brain asymmetry in vervet monkeys. Plos One. 6:e28243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey SH, Vinton D, Norlund R, Grafton ST. 2005. Cortical topography of human anterior intraparietal cortex active during visually guided reaching. Cogn Brain Res. 23:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannon PJ, Kheck NM, Braun AR, Holloway RL. 2005. Planum parietale of chimpanzees and orangutans: a comparative resonance of human-like planum temporale asymmetry. Anat Rec. 287:1128–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing M, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, Tigges J, Mirra SS. 1994. Neuropathology and apolipoportein E profile of aged chimpanzees: implications of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 91:9382–9386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing M, Tigges J, Mori H, Mirra SS. 1997. Beta-amyloid (A beta) deposition in the brains of aged orangutans. Neurobiol Aging. 18:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilissen E, Hopkins WD. 2013. Asymmetries in the parietal operculum in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in relation to handedness for tool use. Cereb Cortex. 23:411–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg G, Randerath J. 2015. Shared neural substrates of apraxia and aphasia. Neuropsychologia. 75:40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Robles A, Hopkins WD, Schapiro SJ, Sherwood CC. 2015. Relaxed genetic control of cortical organization in human brains compared to chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112(48):14799–14804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Robles A, Hopkins WD, Schapiro SJ, Sherwood CC. 2016. The heritability of chimpanzee and human brain asymmetry. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 283:20161319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall J. 1986. The chimpanzees of Gombe: patterns of behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grecucci A, Rubicondo D, Suiugzdaite R, Surian L, Job R, Dundar M, Nosarti C. 2016. Uncovering the social deficits in the autistic brain. A source-based morphometric study. Front Neurosci. 10:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber T, Clay Z, Zuberbuhler K. 2010. A comparison of bonobo and chimpanzee tool use: evidence for a femle bias in the Pan lineage. Anim Behav. 80:1023–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD. 2013. Behavioral and brain asymmetries in chimpanzees: a case for continuity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1288:27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Keebaugh AC, Reamer LA, Schaeffer J, Schapiro SJ, Young LJ. 2014. Genetic influences on receptive joint attention in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Sci Rep. 4:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Meguerditchian A, Coulon O, Misiura M, Pope SM, Mareno MC, Schapiro SJ. 2017. Motor skill for tool-use is associated with asymmetries in Broca’s area and the motor hand area of the precentral gyrus in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Behav Brain Res. 318:71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Reamer L, Mareno MC, Schapiro SJ. 2015. Genetic basis for motor skill and hand preference for tool use in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Proc Biol Sci. 282(1800):20141223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Russell JL, Cantalupo C. 2007. Neuroanatomical correlates of handedness for tool use in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): implication for theories on the evolution of language. Psychol Sci. 18:971–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Russell JL, Schaeffer J. 2014. Chimpanzee intelligence is heritable. Curr Biol. 24:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WD, Russell JL, Schaeffer JA, Gardner M, Schapiro SJ. 2009. Handedness for tool use in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): sex differences, performance, heritability and comparion to the wild. Behaviour. 146:1463–1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen AG, Mous SE, White T, Posthuma D, Polderman TJC. 2015. What twin studies tell us about heritability of brain development, morphology and function. Neurpsychol Rev. 25(1):27–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Frey SH. 2004. The neural basis of complex tool use in humans. Trends Cogn Sci. 8:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasparek T, Marecek R, Schwarz D, Prikryl R, Vanicek J, Mikl M, Ceskova E. 2010. Source-based morphometry og gray matter volume in men with first-episode schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. 31:300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochunov PV, Glahn DC, Fox PT, Lancaster JL, Saleem KS, Shelledy W, Zilles K, Thompson PM, Coulon O, Mangin JF, et al. 2010. Genetics of primary cerebral gyrification: heritability of length, depth and area of primary sulci in an extended pedigree of Papio baboons. Neuroimage. 53:1126–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J, Boesch C. 2008. Sexual differences in chimpanzee sociality. Int J Primatol. 29:65–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre H, Goldman AL, Sambataro F, Verchinski BA, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR, Mattay VS. 2012. Normal age-related brain morphometric changes: nonuniformity across cortical thickness, surface area and gray matter volume? Neurobiol Aging. 33:617.e611–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoy F, Cai Q, Bogart SL, Dubois J, Coulon O, Monzalvo K, Fischer C, Glasel H, Van der Haegen L, Benezit A, et al. 2015. New human-specific brain landmark: the depth asymmetry of superior temporal sulcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 112(4):1208–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonsdorf EV, Eberly LE, Pusey AE. 2004. Sex differences in learning in chimpanzees. Nature. 428:715–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani JC, Watts DP. 2005. Correlates of territorial boundary patrol behaviour in wild chimpanzees. Anim Behav. 70:1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi SS, Van Schaik CP, Pusey AE. 2003. Sex differences in termite fishing among Gombe chimpanzees In: De Waal FBM, Tyack PL, editors. Animal social complexity: intelligence, culture and individualized societies. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- Perez SE, Raghanti MA, Hof PR, Kramer L, Ikonomovic MD, Lacor PN, Erwin JM, Sherwood CC, Mufson EJ. 2013. Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the neocortex and hippocampus of the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). J Comp Neurol. 521:4318–4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rektorova I, Biundo R, Marecek R, Weis L, Aarsland D, Antonini A. 2014. Grey matter chnages in cognitively impaired Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS One. 9:e85595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Kochunov PV, Lancaster JL, Sheeledy W, Glahn D, Blangero J, Fox PT. 2007. Heritability of brain volume, surface area and shape: an MRI study in an extended pedigree of baboons. Hum Brain Mapp. 28:576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Kochunov PV, Zilles K, Shelledy W, Lancaster JL, Thompson P, Duggirala R, Blangero J, Fox PT, Glahn DC. 2010. On the genetic architecture of cortical folding and brain volume in primates. Neuroimage. 53:1103–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen RF, Farberg AS, Gearing M, Dooyema J, Long PM, Anderson DC, Davis-Turak J, Coppola G, Geschwind DH, Pare JF, et al. 2008. Tauopathy with paired helical filaments in an aged chimpanzee. J Comp Neurol. 509:259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz CM, Morgan DB, Hopkins WD. 2016. Lateralization and performance asymmetries in the temite fishing of wild chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo. Am J Primatol. 78:1190–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Rumbaugh ES. 1986. Ape language: From conditioned response to symbol. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Rumbaugh ES, Lewin R. 1994. Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind. New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood CC, Gordon AD, Allen JS, Phillips KA, Erwin JM, Hof PR, Hopkins WD. 2011. Aging of the cerebral cortex differs between humans and chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:13029–13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker RW, Wallup KR, Beck BB. 2011. Animal tool behavior: the use and manufacture of tools by animals. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobniak I, Flitney DE, et al. 2004. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation of FSL. Neuroimage. 23(S1):208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout D, Chaminade T. 2012. Stone tools, language and the brain in human evolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 367:75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strike LT, Couvy-Duchesne B, Hansell NK, Cuellar-Partida G, Medland SE, Wright MJ. 2015. Genetics and brain morphology. Neuropsychol Rev. 25(1):63–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terribilli D, Schaufelberger MS, Duran FL, Zanetti MV, Curiati PK, Menezes PR, Scazufca M, Amaro E Jr., Leite CC, Busatto GF. 2011. Age-related gray matter volume changes in the brain during non-elderly adulthood. Neurobiol Aging. 32:354–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaesen K. 2012. The cognitive bases of human tool use. Behav Brain Sci. 35:203–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss PH, Ubben SD, Kaesberg S, Kalbe E, Kessler J, Liebig T, GFink GR. 2015. Where language meets meaningful action: a combined behavior and lesion analysis of aphasia and apraxia. Brain Struct Funct. 221:563–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew WC, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin CEG, Wrangham RW, Boesch C. 1999. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature. 399:682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten A, Goodall J, McGrew W, Nishida T, Reynolds V, Sugiyama Y, Tutin C, Wrangham R, Boesch C. 2001. Charting cultural variation in chimpanzees. Behaviour. 138:1489–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Groth KM, Pearlson G, Schreffen DJ, Calhoun VD. 2009. Source-based morphometry: the use of independent component analysis to identify gray matter differences with application to schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapp. 30:711–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith SM. 2001. Segmentation of the brain MR images through hidden Markov random filed model and expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 20:45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.