Abstract

The interplay of dopaminergic striatal D1–D2 circuits is thought to support working memory (WM) by selectively filtering information that is to be remembered versus information to be ignored. To test this theory, we conducted an experiment in which healthy participants performed a visuospatial working memory (VSWM) task after ingesting the D2-receptor agonist cabergoline (or placebo), in a randomized, double-blinded, crossover design. Results showed greater interference from distractors under cabergoline, particularly for individuals with higher baseline dopamine (indicated by WM span). These findings support computational theories of striatal D1–D2 function during WM encoding and distractor-filtering, and provide new evidence for interactive cortico-striatal systems that support VSWM capacity and their dependence on WM span.

Keywords: Agonist, Basal ganglia, Cabergoline, Capacity, Dopamine, D2, Individual differences, Prefrontal cortex, Striatum, Visuospatial working memory, Working memory

Working memory (WM) is a cognitive process for maintaining and manipulating information over short time intervals in the absence of perceptual input (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). WM integrity influences a range of cognitive control and abstract problem-solving processes (Kane & Engle, 2002). Cortico-striatal interactions involving the neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) have been proposed as key mechanisms underlying distinct aspects of WM, in particular, the control over which information is updated to be maintained in WM (“go”) and which should be ignored (“no-go”; Cools, 2008, 2011; Frank & Fossella, 2011; Frank, Loughry, & O’Reilly, 2001; Frank & O’Reilly 2006).

In pursuit of goals, it is at times necessary to selectively overwrite certain WM representations while robustly maintaining others intact. This paradox has been resolved by the prefrontal-basal ganglia working memory model (PBWM; Frank et al., 2001; O’Reilly & Frank, 2006) via two striatal-thalamo-cortical circuits associated with striatal D1 and D2 receptors, respectively. Computations by separate circuits allow for dynamic updating and maintenance of WM, by D1-mediated updating (“go” signaling) and D2-mediated maintenance (“no-go” signaling). This mechanism is proposed to resolve the dilemma between achieving stability versus flexibility in WM (Cools, 2011; Cools, Miyakawa, Sheridan, & D’Esposito, 2010; Fallon, van der Schaaf, ter Huurne, & Cools, 2017; Fallon, Zokaei, Norbury, Manohar, & Husain, 2017; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006; Moustafa, Sherman, & Frank, 2008).

These ideas have received empirical support from lesion studies (Baier et al., 2010), imaging work (Chatham, Frank & Badre, 2014; McNab & Klingberg, 2008; Slagter et al., 2012), gene studies (Colzato, Slagter, de Rover, & Hommel, 2011). and studies with Parkinson’s patients (Moustafa et al., 2008). Pharmacological experiments have supported the involvement of striatal DA in regulating the stability and flexibility of WM in continuous-performance tasks, requiring selective updating and maintenance of WM representations (Fallon, van der Schaaf, et al. 2017; Fallon, Zokaei, et al., 2017; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006). However, there is very little pharmacological evidence that directly tests the PBWM theory of WM, particularly the role of D2 receptors in filtering unwanted distractors.

The present work aimed to provide evidence in the context of visuospatial working memory (VSWM) for a central prediction of the PBWM model that agonistic D2 receptor stimulation should result in decreased no-go signaling to the cortex. We reasoned that this prediction could be tested using the DA agonist cabergoline, which at low doses has relatively low affinity for D1 receptors and high affinity for D2 receptors (Biller et al., 1996; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006; Gerlach et al., 2003; Ichikawa & Kojima, 2001; Millan et al., 2002; Stocchi et al., 2003).

To understand the counterintuitive prediction of reduced no-go signaling due to a D2 agonist, it is important to note that DA is inhibitory within striatal cells containing D2 receptors, which are required to suppress unwanted actions (Frank & O’Reilly, 2006). Thus, postsynaptic effects of cabergoline should be such that the inhibitory D2 pathway is itself tonically inhibited, thereby reducing no-go signaling to the cortex. In the VSWM task, reduced no-go signaling should manifest as enhanced encoding of distractor locations as well as target locations (cf. Fallon, van der Schaaf, et al., 2017).

Experiment and predictions

We investigated effects on VSWM from ingesting a low dose (1.25 mg) of cabergoline, in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover experiment. VSWM is proposed to have severe capacity limitations, capable of representing an upper limit of approximately 4 ± 1 items, or chunks of information, for up to a few seconds (Cowan, 2001; see also Awh, Barton, & Vogel, 2007; Fukuda, Awh, & Vogel, 2010; Luck & Vogel, 1997, 2013; Vogel, McCollough, & Machizawa, 2005; Zhang & Luck, 2008). However, VSWM capacity can be reduced by distraction (Vogel et al., 2005). In the present VSWM experiment, participants performed a standard yes/no recognition task (see Fig. 1a). Participants were required to remember the locations of three targets (Condition 3), three targets with two distractors (Condition 3+2), or five targets (Condition 5; as in Baier et al., 2010). A VSWM capacity decrement, due to the presence of distractors in the array, can be computed as a contrast between Condition 3+2 and Condition 3.

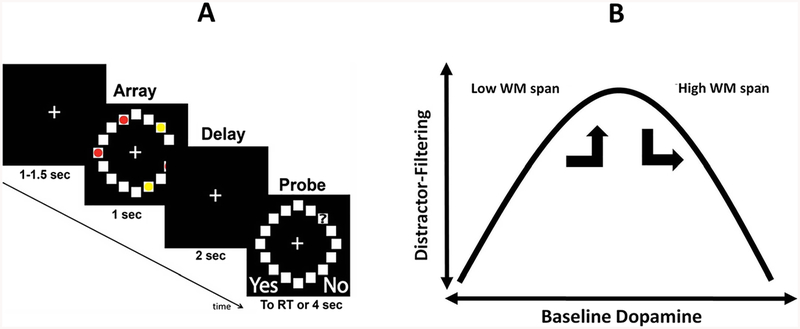

Fig. 1.

a Trial events and temporal parameters of the visuospatial working memory (VSWM) task. Participants responded whether the square currently occupied by the probe (?) had been occupied by a red dot (in the preceding visual array). Participants were instructed to ignore yellow dots. Visual arrays showed either 3 targets (Condition 3), 3 targets plus two distractors (Condition 3+2; depicted in Fig.), or 5 targets (Condition 5). See main text for additional details. b Hypothetical inverted-U function relating baseline DA to distractor-filtering ability. It was predicted that cabergoline would push individuals with higher working memory (WM) span out of an optimal position on the curve, resulting in a greater VSWM capacity decrement for these individuals due to the presence of distractors, compared to placebo. In contrast, cabergoline would push individuals with lower WM span into the optimal position, resulting in a smaller VSWM capacity decrement for these individuals due to the presence of distractors, compared to placebo

Due to inhibition of the inhibitory D2 pathway by DA stimulation, we expected that cabergoline would interfere with performance by reducing no-go signaling to the cortex (Frank & O’Reilly, 2006; see their Table 1). This would manifest under cabergoline as a diminished ability to selectively gate interfering items, leading to increased encoding of distractor locations as well as target locations. This would manifest under cabergoline as a steeper decrement in VSWM capacity when distractors were present in the array.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for K, the measure of visuospatial working memory capacity

| K | K w/covar | |

|---|---|---|

| M (SE) | M(SE) | |

| 3 | 2.482 (.065) | 2.482 (.063) |

| 3+2 | 2.338 (.076) | 2.338 (.076) |

| 5 | 3.356 (.151) | 3.356 (.152) |

| M (SE) | M (SE) | |

| 3P | 2.410 (.092) | 2.410 (.093) |

| 3C | 2.554 (.073) | 2.554 (.066) |

| 3+2P | 2.285 (.127) | 2.285 (.126) |

| 3+2C | 2.390 (.071) | 2.390 (.072) |

| 5P | 3.256 (.214) | 3.256 (.217) |

| 5C | 3.456 (.141) | 3.456 (.141) |

Note. ANOVA and ANCOVA results are reported in main text. 3, 3 + 2, and 5 refer to task conditions (3 targets, 3 targets plus 2 distractors, 5 targets). P and C refer to drug conditions (placebo and cabergoline). The covariate (covar) was z-score normalized Ospan. N = 25

Individual differences and trait-state interactions

It is becoming increasingly clear that individual differences in baseline DA can strongly moderate the effects of agonist/antagonist drug agents (for a review, see Cools & D’Esposito, 2011). We expected that effects of cabergoline would be strongly moderated by preexisting individual differences in DA (as in Cools et al., 2009; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006). To account for such individual differences, we measured WM span, which is positively related to baseline DA levels (Cools, Gibbs, Miyakawa, Jagust, & D’Esposito, 2008; Landau, Lal, O’Neil, Baker, & Jagust, 2009). We hypothesized that further D2 stimulation by cabergoline would make these individuals particularly susceptible to distractibility (cf. Cools & D’Esposito, 2011).

Therefore, as part of the experimental design, participants performed the operation span task, a state-of-the-art measure of WM span (Ospan; Unsworth, Heitz, Schrock, & Engle, 2005). Ospan requires serial order memory for letters, with an interleaved distractor task (solving arithmetic problems). Ospan performance is thought to depend on domain-general executive attention, considered a trait-like ability (Ilkowska & Engle, 2010) to maintain task-relevant information in WM in the face of interference, in a goal-directed manner (Engle, Tuholski, Laughlin, & Conway, 1999; Kane & Engle, 2002). This makes Ospan a plausible candidate measure to account for variance in possible drug effects on distractor filtering in VSWM.

With respect to a hypothetical inverted-U shaped function (see Cools & D’Esposito, 2011) relating baseline DA to distractor-filtering ability (see Fig. 1b), we expected that ingesting cabergoline would push individuals with lower DA (using low WM span as a proxy) into a more optimal position on the curve, compared with their usual level of distractor-filtering ability under placebo. This shift in psycho-pharmacological state would manifest behaviorally as a smaller decrement in VSWM capacity due to the presence of distractors, under cabergoline versus placebo (for individuals with lower WM span).

In contrast, we expected that ingesting cabergoline would push individuals with higher DA (higher WM span) into a less optimal position on this function, relative to their usual level of distractor-filtering ability under placebo. This shift in psychopharmacological state would manifest as a larger decrement in VSWM capacity, under cabergoline versus placebo (for individuals with higher WM span).

Novelty

Prior work has shown cognitive declines for individuals with higher WM span, and improvements for individuals with lower WM span, due to ingesting the D2-agonist bromocriptine (Gibbs & D’Esposito, 2005; Kimberg, D’Esposito, & Farah, 1997). However the present study is novel in that these counterintuitive predictions were motivated by an explicit theoretical framework (PBWM), specifically, concerning how D1 and D2 circuits work together to gate WM representations. Moreover, the present work makes a new contribution to the study of DA and WM, by accounting for individual differences in reference to a published normative distribution of an extensively validated measure of WM span (Redick et al., 2012). We suggest that this is an important innovation for the field of research into how individual differences interact with pharmacological interventions, in particular, to facilitate comparisons across experiments.

Method

Ethics statement

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brown University. Participants gave written informed consent and were compensated for their participation.

Participants

A total of 30 individuals (12 female) participated, reporting normal or corrected-to-normal vision and proficiency in written and spoken English. Participants reported to be right-handed with the exception of one left-handed individual. A prior report has published data from the same participants in a different task (Cavanagh, Masters, Bath, & Frank, 2014).

Three participants did not complete the study due to adverse reactions to cabergoline. Also, as reported in more detail below, two individuals were identified as outliers on Ospan, and their data were excluded. This left a final sample of N = 25 (age M = 20.56 years, SD = 2.256, range: 18–26 years, 12 female).

Procedure

Participants completed two experimental sessions at least 1 week apart, with randomized double-blinded administration of either 1.25 mg of cabergoline or identical-looking placebo. Cabergoline was chosen as the pharmacological agent to manipulate striatal DA, over alternatives such as, for example, bromocriptine, for similar motivations as in previous work (e.g., Cavanagh et al., 2014; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006). Specifically, at lower doses, and with fewer negative side effects, cabergoline has relatively high affinity for D2 receptors and low affinity for D1 receptors (for extensive and detailed prior justification for using cabergoline to manipulate D2 function, please see Frank & O’Reilly, 2006, main article and supplemental material; see also Biller et al., 1996; Gerlach et al., 2003; Ichikawa & Kojima, 2001; Millan et al., 2002; Stocchi et al., 2003).

Ospan

This task measured WM span. The task was programmed in E-Prime (Schneider, Eschman, & Zuccolotto, 2002) and presented on a computer. To-be-remembered letters were presented successively at fixation, for subsequent serial order recall, in between performances of an interleaved distractor task (solving arithmetic equations; for complete details see Unsworth et al., 2005). Partial-credit scoring was used, so that one point was assigned for each item recalled in correct serial position for each trial (set sizes 3–7), regardless of whether all items were correctly recalled. Scores could range from zero to 75. Ospan was performed in the first experimental session, immediately after ingesting either placebo or cabergoline (i.e., prior to the drug taking effect if cabergoline was administered in the first session).

VSWM task

This measured VSWM capacity. The task was programmed in Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainerd, 1997) and presented on a computer. Figure 1a depicts trial events and temporal parameters (cf. Baier et al., 2010). After a variable fixation of 1 to 1.5 seconds, participants were shown a circular array of 16 squares, with some of the squares containing colored dots. Participants were instructed to remember the locations of red dots (targets) but to ignore yellow dots (distractors). Three red dots were presented as Condition 3. Three red dots plus two yellow dots were presented as Condition 3+2 (distractor condition). Five red dots were presented as Condition 5. The visual array was presented for second, followed by a 2-second delay period (fixation). Then, the circular array of 16 squares was shown again, but with a memory probe (“?”) in one of the squares. Using a joystick, participants responded yes/no, whether the square containing the probe had just contained a red dot (left button = yes, right button = no). There was a 4-second response deadline. Condition for each trial was pseudorandomly determined, with the constraint that there were 50 trials for each condition (150 trials total). Locations of targets, distractors and probes for each trial were pseudorandomly determined, with the constraint that positive and negative probes each occurred on 50% of trials. The task was initiated 180 minutes following ingestion on average and required an average of 20 minutes to complete.

Results

Ospan

As noted earlier, two individuals were identified as outliers, with Ospan scores that were more than two standard deviations below the sample mean (M = 64.963, SD = 11.315) and corresponding to the fifth percentile of a published normative distribution (Redick et al., 2012, their Table 4). Data from these individuals were excluded, leaving a final sample of 25 (as noted earlier). Ospan scores in the final sample (N = 25) ranged from 54 to 75 (M = 67.760, SD = 5.348). This range would correspond to the upper 50% of a published normative distribution (Redick et al., 2012, their Table 4). Indices of normality were adequate (−1.008 for skew and .841 for kurtosis) in the final sample.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression models predicting the dependent variable KΔDD

| Coefficients | Model summary | Change statistics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | p | R2 | R2adj | F | p | df1, df2 | R2chng | Fchng | p | df1, df2 | ||

| 1.1 | zOspan | −.26 | −2.58 | .02 | .27 | .23 | 6.63 | .02 | 1, 18 | .27 | 6.63 | .02 | 1,18 |

| 1.2 | zOspan | −.23 | −2.29 | .04 | .34 | .26 | 4.30 | .03 | 2, 17 | .07 | 1.70 | .21 | 1, 17 |

| 1.2 | FA-in P | .94 | 1.31 | .21 | |||||||||

| 1.3 | zOspan | −.16 | −1.83 | .09 | .56 | .48 | 6.73 | <.01 | 3, 16 | .22 | 8.03 | .01 | 1, 16 |

| 1.3 | FA-in P | 1.24 | 2.01 | .06 | |||||||||

| 1.3 | FA-in C | −2.09 | −2.83 | .01 | |||||||||

| 2.1 | zOspan | −.26 | −2.58 | .02 | .27 | .23 | 6.63 | .02 | 1, 18 | .27 | 6.63 | .02 | 1,18 |

| 2.2 | zOspan | −.20 | −2.13 | .04 | .45 | .38 | 6.85 | <.01 | 2, 17 | .18 | 5.44 | .03 | 1, 17 |

| 2.2 | FA-in C | −1.84 | −2.33 | .03 | |||||||||

| 2.3 | zOspan | −.16 | −1.83 | .09 | .56 | .48 | 6.73 | <.01 | 3, 16 | .11 | 4.03 | .06 | 1, 16 |

| 2.3 | FA-in C | −2.09 | −2.83 | .01 | |||||||||

| 2.3 | FA-in P | 1.24 | 2.01 | .06 | |||||||||

Note. Abbreviations: FA-in refers to false-alarm errors when the probe appeared in a location that had been occupied by a distractor. P refers to placebo, C refers to cabergoline. Data were restricted to individuals who made at least one FA-in error under placebo or cabergoline (N = 20). Ospan was z-score normalized (zOspan)

VSWM capacity

Our dependent measure was a widely used estimate of VSWM capacity, K (Rouder, Morey, Morey, & Cowan, 2011; computed as K = N* [hit rate minus false alarm rate]), where N = number of targets (results were qualitatively the same in all respects using the signal detection measure d’). First, we assessed basic experimental effects of condition and drug, without taking into account individual differences in WM span. In particular, we sought to confirm that there was a capacity decrement in Condition 3+2 (distractor condition) relative to condition 3. A 3 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on K, with within-subjects factors of condition (3, 3+2, 5), and drug (placebo, cabergoline). ANOVA results showed a significant main effect of condition, F(2, 23) = 44.346, p < .001, ηp2 = .794. The main effect of drug was not significant, F(1, 24) = 1.453, p = .240, ηp2 = .057, and the Condition × Drug interaction was not significant (F < 1). Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests confirmed that each pairwise comparison between conditions was significantly different (p < .001; see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Critically, K was significantly lower in Condition 3+2 versus Condition3. This means that there was a significant decrement in VSWM capacity due to the presence of distractors in the visual array, replicating an established finding (e.g., Vogel et al., 2005).

Next, to account for individual differences in WM span, a 3 × 2 repeated-measures ANCOVA was conducted on K, with normalized Ospan scores entered as covariate. ANCOVA results showed a significant Condition × Drug interaction, F(2, 22) = 4.475, p = .023, ηp2 = .289, and a significant Condition × Drug × Ospan interaction, F(2, 22) = 4.607, p = .021, ηp2 = .291. No other effect was significant (p > .802). This finding indicates that effects of cabergoline were moderated by preexisting individual differences in WM span (serving as a proxy measure of individual differences in baseline DA).

Distractor-filtering versus load

To clarify the interactions observed in the omnibus test, two separate ANCOVAs were performed, each with two levels of condition. The first ANCOVA assessed whether the Condition × Drug × Ospan interaction in the omnibus test was related to the manipulation of distractor filtering (i.e., Condition 3 vs. Condition 3+2). Here the Condition × Drug interaction was not significant (unlike the omnibus test), F < 1, but the Condition × Drug × Ospan interaction was again significant (like the omnibus test), F(1, 23) = 9.631, p = .005, ηp2 = .295.

The second ANCOVA assessed whether the Condition × Drug × Ospan interaction in the omnibus test was related to the manipulation of load per se (i.e., Condition 3 vs. Condition 5). Here the Condition × Drug interaction was not significant (unlike the omnibus test), F < 1, and the Condition × Drug × Ospan interaction was not significant (unlike the omnibus test), F < 1.

Together, these results indicate that the drug effect interacted with the manipulation of distractor filtering (i.e., Condition 3 vs. Condition 3+2) rather than with the manipulation of load per se(i.e., Condition 3 vs. Condition 5). Incidentally, these results also indicate that drug effects were not different for conditions that were putatively “supracapacity” (Condition 5) versus “subcapacity” (Condition 3).

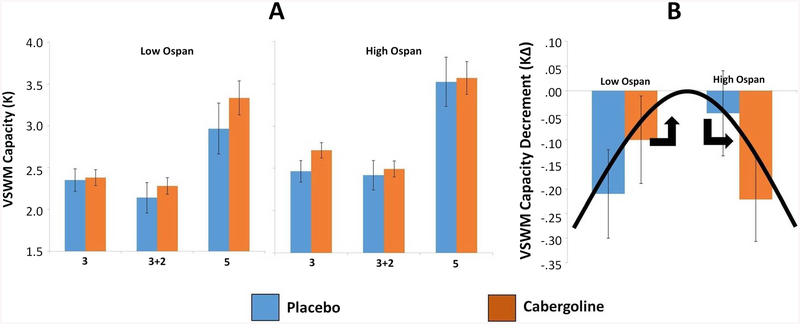

Figure 2a shows K across experimental conditions separately for low and high Ospan groups (median split; Mdn = 68; high span N = 13, low span N = 12). Paired t tests comparing cabergoline versus placebo across conditions, separately for low and high Ospan groups, showed no significant difference (p > .319).

Fig. 2.

Results for visuospatial working memory (VSWM) performance. a K for low (left) and high (right) Ospan groups across Task × Drug conditions (placebo = blue, cabergoline = red). 3, 3 + 2, and 5 refer to task conditions (respectively, 3 targets, 3 targets plus 2 distractors, 5 targets). Error bars represent one standard error above and below the mean. The Condition × Drug × Ospan interaction was significant in ANCOVA, p = .02 (normalized Ospan as continuous covariate). Pairwise tests were not significant, p > .05. b KΔ, the VSWM capacity decrement due to the presence of distractors, under placebo (blue) or cabergoline (red), separately for low and high Ospan groups. The hypothetical inverted-U function relating baseline DA to distractor-filtering ability is superimposed. Error bars represent one standard error above and below the mean. The Drug × Ospan interaction was significant in ANCOVA, p < .01 (z-score normalized Ospan as continuous covariate). High/low Ospan groups formed by median-split; (Mdn = 68; high span N = 13, low span N = 12). (Color figure online)

Ospan was significantly positively correlated with K Condition 3 under cabergoline, r(23) = .451, p = .024. Correlations between Ospan and K in other cells of the experimental design were consistently positive but not significant (Table 2, left-most column). Testing for heterogeneity among these correlations (Meng, Rosenthal, & Rubin, 1992) between Ospan and K across the six Task × Drug conditions revealed that there were not significant differences among magnitudes of these correlations, χ2(5) = 5.194, p > .05.

Table 2.

Relationships among working memory span (Ospan) and visuospatial working memory capacity (K) across task and drug conditions

| Ospan | K3P | K3+2P | K5P | K3C | K3+2C | K5C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ospan | – | ||||||

| K3P | .058 | – | |||||

| K3+2P | .220 | .880** | – | ||||

| K5P | .115 | .665** | .627** | – | |||

| K3C | .451* | .235 | .158 | .445* | – | ||

| K3+2C | .028 | .318 | .112 | .621** | .634** | – | |

| K5C | .196 | .160 | −.016 | .430* | .628** | .663** | – |

Note. N = 25. Correlation coefficient is Pearson’s r. P indicates placebo, C indicates cabergoline. 3, 3+2, and 5 refer to task conditions (3 targets, 3 targets plus 2 distractors, 5 targets).

p < .01,

p < .05

Capacity decrement (KΔ)

To specifically address our hypotheses about distractor filtering, following Baier et al. (2010), a capacity decrement index for K (KΔ) was computed for each individual (Condition 3+2 minus Condition 3). One-way ANCOVA on KΔ showed a significant effect of drug, F(1, 23) = 9.358, p = .006, ηp2 =.289, and a significant Drug × Ospan interaction, F(1, 23) = 9.631, p = .005, ηp2 = .295.

The main effect of drug was a greater decrement in VSWM capacity (more negative KΔ scores) under cabergoline (M = −.163, SE = .054) versus placebo (M = −.125, SE = .060). However, the drug effect interacted with individual differences in baseline WM span in a crossover manner (see Fig. 2b; Ospan groups formed by median split as in Fig. 2a). Specifically, Fig. 2b shows that for higher Ospan individuals, KΔ was more negative under cabergoline (M = −.222, SE = .049) versus placebo (M = −.046, SE = .105), but for lower Ospan individuals this pattern was reversed, with KΔ more negative under placebo (M = −.210, SE = .0218) versus cabergoline (M = −.100, SE = .406). Consistent with these observations, the drug-difference score for KΔ (cabergoline minus placebo; KΔDD) was positive for lower Ospan individuals (M = .110, SE = .140), but negative for higher Ospan individuals (M = −.175, SE = .131). However, these were not significantly different, t(23) = 1.485, p = .151. Also, paired t tests comparing KΔ under placebo versus cabergoline separately for high/low Ospan groups showed no significant difference for higher Ospan, t(12) = 1.334, p = .207, or lower Ospan, t(11) = −.783, p = .450.

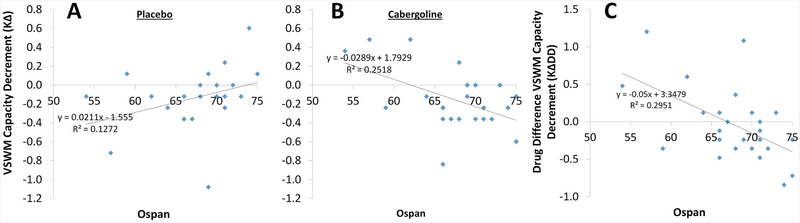

Converging with these results, Ospan was not significantly correlated with KΔ under placebo, r(23) = .357, p = .080 (Fig. 3a), but was significantly negatively correlated with it under cabergoline (Fig. 3b), r(23) = −.502, p = .011. Noting the opposite signs of these relationships, we tested whether they were significantly different from each other. Controlling for their intercorrelation, r(23) = −.243, p = .243, these correlations were significantly different from each other, Z = −2.657, p < .05, 95% CI for the difference (−1.608, −.243) (Meng et al., 1992). Moreover, the drug-difference score for KΔ (cabergoline minus placebo; KΔDD) was negatively correlated with Ospan, r(23) = −.543, p = .005 (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Relationships between Ospan and KΔ, the visuospatial working memory (VSWM) capacity decrement due to the presence of distractors, under placebo (a), and cabergoline (b). Ospan was not significantly correlated with KΔ under placebo, r(23) = .357, p = .080. Ospan was significantly negatively correlated with KΔ cabergoline, r(23) = −.502, p = .011. These correlations were significantly different from each other, Z = −2.657, p < .05, 95% CI for the difference (−1.608, −.243) (Meng et al., 1992). c Relationship between Ospan and KΔDD, the drug difference (cabergoline minus placebo) for the VSWM capacity decrement (KΔ) due to the presence of distractors. Scores below the zero point (negative KΔDD) indicate the participant was more impaired at filtering distractors under cabergoline versus placebo. KΔDD was significantly negatively correlated with Ospan, r(23) = −.543, p = .005

Together, these results indicate that under placebo, individuals with higher WM span were less impaired at filtering distractors than were individuals with lower WM span. But under cabergoline, individuals with higher WM span were more impaired at filtering distractors than were individuals with lower WM span.

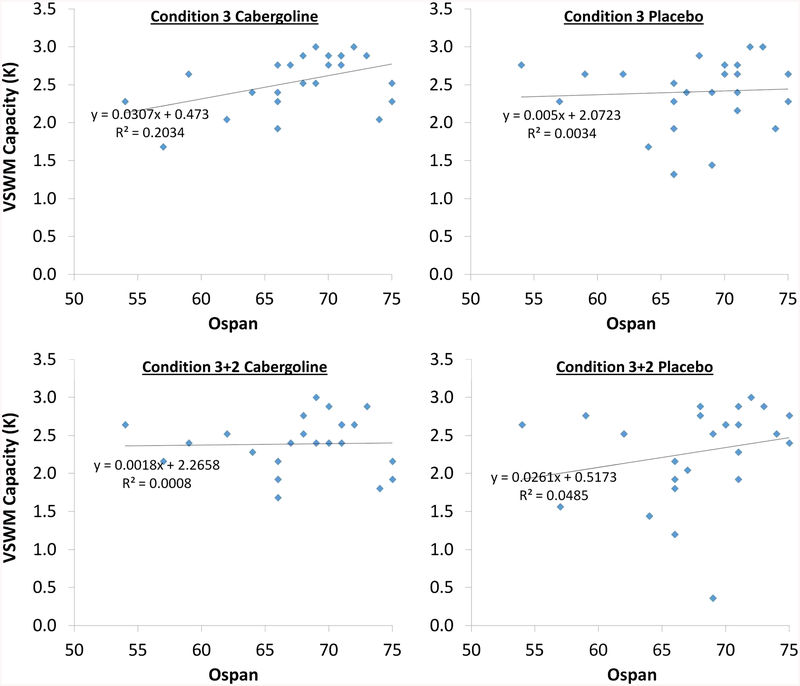

Next, partial correlations were used to determine which cells of the experimental design, among the four that were involved in the computation of KΔDD, contributed the most predictive variance to the relationship between Ospan and KΔDD (scatterplots in Fig. 4). The zero-order correlation between Ospan and KΔDD, r(23) = −.543, p = .005, was substantially reduced after controlling for K Condition 3 cabergoline, partial-r(22) = −.492, p = .015. And it was also reduced after controlling for K Condition 3+2 placebo, partial-r(22) = −.513, p = .010. In contrast, the zero-order correlation between Ospan and KΔDD was basically unaffected after controlling for K Condition 3 placebo, partial-r(22) = −.542, p = .006, and was even substantially increased by controlling for K Condition 3+2 cabergoline, partial-r(22) = −.606, p = .002.

Fig. 4.

Relationships between Ospan and K in the four Task × Drug conditions involved in the computation of KΔDD. Ospan was significantly positively correlated with K in Condition 3 cabergoline, r(23) = .451, p < .05. Other relationships shown here were not significant (see Table 2)

These results indicate that among the four Condition × Drug conditions that were involved in the computation of KΔDD, the relationship between Ospan and KΔDD was most directly related to variance in Condition 3 cabergoline and Condition 3+2 placebo. This is because the relationship between Ospan and KΔDD was reduced when controlling for variance in Condition 3 cabergoline and in Condition 3+2 placebo, but was unaffected or increased, respectively, by controlling for variance in Condition 3 placebo and Condition 3+2 cabergoline (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). This converges with results reported earlier, namely, that Ospan was most strongly correlated with K in Condition 3 cabergoline, as well as Condition 3+2 placebo (see again Table 2).

Distractor-location encoding

Committing a false alarm when a distractor had just occupied the location of the probe (FA-in error) should be particularly diagnostic regarding the hypothesis that cabergoline was associated with the increased encoding of distractor locations. Therefore we next examined individual differences in the tendency to commit FA-in errors. Out of 25 negative probe trials under Condition 3+2 there were only 13 trials in which a distractor had occupied the location of the probe. Five individuals did not commit any FA-in errors under either placebo or cabergoline. We therefore selected a subsample of individuals who committed at least one FA-in error under placebo or cabergoline, or both (N = 20).

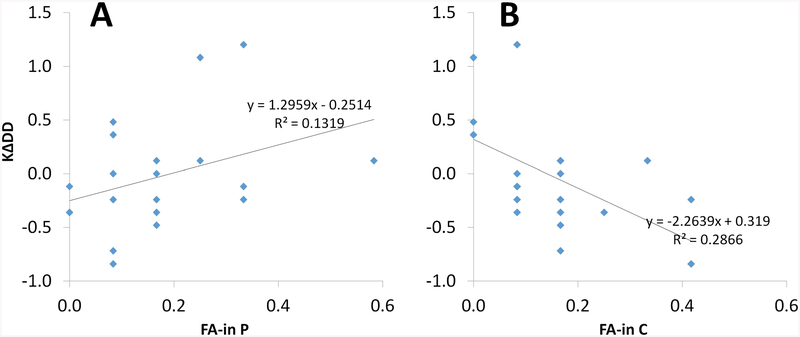

FA-in error rates did not differ between drug conditions, t(19) = .418, p = .681 (placebo M = .171, SE = .032; cabergoline M = .154, SE = .027). However, FA-in error rates under cabergoline were negatively correlated with KΔDD, the drug effect on the VSWM capacity decrement, r(18) = −.535, p = .019 (see Table 3). This means that individuals with a greater VSWM capacity decrement under cabergoline committed more FA-in errors under cabergoline. To further clarify these results, we tested whether the magnitudes of the relationships between KΔDD and FA-in errors (under cabergoline vs. placebo; see Fig. 5a and b, respectively), were significantly different from each other. Controlling for their intercorrelation, r(18) = .107, p = .653, these correlations were significantly different from each other, Z = −3.224, p < .05, 95% CI for the difference (−1.571, −.382) (Meng et al., 1992).

Table 3.

Relationships among working memory span (Ospan), the drug effect on the visuospatial working memory capacity decrement (KΔDD), and false-alarm errors under cabergoline (C) versus placebo (P), when the probe appeared in a location that had been occupied by a distractor (FA-in)

Note. Data were restricted to individuals who made at least one FA-in error under placebo or cabergoline (N = 20). Coefficient is Pearson’s r.

p < .05

Fig. 5.

Relationships between KΔDD, the drug effect on the visuospatial working memory (VSWM) capacity decrement due to the presence of distractors, and FA-in errors under cabergoline (a) and under placebo (b). Data were restricted to individuals who made at least one FA-in error under placebo or cabergoline (N = 20). FA-in error rates under cabergoline were significantly negatively correlated with KΔDD, r(18) = −.535, p = .015 (a). FA-in errors under placebo were not significantly correlated with KΔDD, r(18) = .363, p = .116 (b). These correlations were significantly different from each other, Z = −3.224, p < .05, 95% CI for the difference (−1.571, −.382) (Meng et al., 1992)

These results show that individuals with a greater VSWM capacity decrement under cabergoline also committed more FA-in errors under cabergoline, while also committing fewer FA-in errors under placebo. As reported earlier, individuals with a greater capacity decrement under cabergoline had higher WM span. However, Ospan was not significantly correlated with FA-in errors under cabergoline or placebo (see Table 3). Indeed, hierarchical multiple regression analysis (see Table 4) showed that FA-in errors under cabergoline accounted for significant unique variance in KΔDD, over-and-above variance accounted for by Ospan and FA-in errors under placebo (yielding incremental prediction of approximately 18%–22%), while FA-in errors under placebo did not account for significant unique variance in KΔDD, while controlling for Ospan or FA-in errors under cabergoline. Results suggest that individual differences in the drug effect on the VSWM capacity decrement can be explained in part by individual differences in the tendency to encode distractors under cabergoline, over and above relationships to WM span.

Discussion

We conclude from the results of the experiment that the D2-receptor agonist cabergoline affected interference from distractors, depending on individual differences in baseline WM span (our proxy measure of individual differences in baseline DA). These complex findings were predicted from the PBWM computational theory (e.g., Hazy, Frank, & O’Reilly, 2007) and are consistent with previous work implicating D2 stimulation in reducing the threshold for updating WM, with concomitant increase in distractibility (Colzato et al., 2011; Cools et al., 2010; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006; Moustafa et al., 2008; Slagter et al., 2012). Mechanistically, within terms of the predictions of the PBWM, increased D2 stimulation indicates a lowered threshold for gating representations into WM due to suppression of no-go signaling to cortex. The net result leads to enhanced updating of the contents of WM (Fallon, Zokaei, et al., 2017; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006). For the ability to filter distractors, a lowered threshold for gating representations would be expected to result in increased encoding of distractor locations as well as better encoding of target locations. Consistent with this reasoning, cabergoline induced a larger decrement in VSWM capacity due to the presence of distractors, again for individuals with higher WM span (who presumably have higher baseline DA; Cools et al., 2008; Landau et al., 2009).

Note that the claim regarding impaired distractor filtering under cabergoline is not based on the effect of cabergoline on K in Condition 3+2, the distractor condition, viewed in isolation. Rather, the claim is based on the effect of cabergoline on the decrement in K, observed by comparing Condition 3 to Condition 3+2. We interpret the interaction with individual differences in WM span to indicate that, as predicted, the net effect of cabergoline was to push individuals with higher WM span out of the optimal position on the hypothetical inverted-U function, and to push individuals with lower WM span into it (see again Fig. 2b). As noted earlier, individuals with higher WM span have higher baseline striatal DA levels (Cools et al., 2008), and it appears that further D2-receptor stimulation by cabergoline made these individuals susceptible to increased distractibility. In contrast, subjects with lower overall DA may benefit from dopaminergic stimulation in terms of updating in a WM task with distractors, as in subjects with ADHD (Frank, Santamaria, O’Reilly, & Wilcutt, 2007).

The present findings are consistent with previous pharmacological experiments showing cognitive impairments for individuals with higher WM span, and improvements for individuals with lower WM span, due to ingesting a D2-receptor agonist (Frank & O’Reilly, 2006; Gibbs & D’Esposito, 2005; Kimberg et al., 1997). Our results are similar to those from a recent cabergoline experiment using a very different WM task paradigm (Fallon, Zokaei, et al., 2017), yet they contain some important differences. They found that cabergoline enhanced the fidelity and precision of visual WM representations when target stimuli were presented alone. However, they found no evidence that participants had confused distractors for targets. In contrast, here we found that cabergoline did cause individuals to encode distractors—a direct prediction of the PBWM model. While we think these differences are likely due to aspects of task design, Fallon, Zokaei, et al. (2017) interpreted these effects as due to “indiscriminate generation of go signals” (p. 735), whereas the PBWM model suggests this is also due to a failure to exert no-go signals to distractors. Interestingly, in the Fallon, Zokaei, et al. (2017) study, the effects of cabergoline were not moderated by individual differences in WM span (digit span), unlike in the present work (Ospan). We think this difference between results across studies may be attributed to the fact that, depending on details of administration, digit span often shows inferior loading on the WM construct compared to Ospan (for a review, see Unsworth & Engle, 2007).

Our results can be interpreted in terms of the traditional “slots” model of VSWM capacity (Awh et al., 2007; Fukuda et al., 2010; Luck & Vogel, 1997, 2013; Zhang & Luck, 2008), in which it is assumed that distractor locations would exert their interference by occupying limited storage capacity that would be better used for target locations. However, it is also possible that updating of distractors can induce reciprocal interference between targets and distractors, along the lines of resource models (see, e.g., Nassar, Helmers, & Frank, 2017). A competing theory invokes limited processing resources to explain VSWM performance rather than limited storage space (Fallon, Zokaei, & Husain, 2016; Ma, Husain, & Bays, 2014). The present experiment was not designed to arbitrate between these theories, and our results may be compatible with interpretation within either framework. Indeed, recent work suggests these frameworks represent extremes along a continuum that can be modulated by reinforcement and incentives (Nassar et al., 2017), and hence may also be subject to dopaminergic effects.

Most previous experiments motivated by the PBWM framework have used various versions of AX-CPT, a continuous performance task with sequentially presented stimuli, or reinforcement learning tasks, to test model predictions (e.g., Frank & O’Reilly, 2006). Thus, the present work is a novel extension of PBWM theory, to predict and explain how D1–D2 circuitry underlies VSWM distractor interference. However, the present VSWM task likely taps into a different set of WM processes than tasks which have been more often used to operationally define WM updating, such as AX-CPT. Specifically, we assessed visual WM for multiple target locations over varied WM loads, while AX-CPT is verbal task which does not vary load. Thus, we extended the investigation of PBWM to a much simpler WM task paradigm, assessing basic WM representation in a more direct manner, focused specifically on distractor interference.

Limitations

We have assumed relative D2 selectivity for cabergoline in the experiment, based on previous work suggesting that cabergoline has relatively high D2 affinity and low D1 affinity (Biller et al., 1996; Frank & O’Reilly, 2006; Gerlach et al., 2003; Ichikawa & Kojima, 2001; Millan et al., 2002; Stocchi et al., 2003). However, some evidence exists that, at much higher doses than in the present work, cabergoline may have a more mixed affinity for D1 and D2 receptors (Brusa et al., 2013; Fariello, 1998). Therefore, it cannot be ruled out that cabergoline also stimulates D1 circuits to some extent and these findings are due to an altered balance of D1–D2 activity, rather than simply changes in go or no-go pathway in isolation.

We have assumed that cabergoline would primarily affect striatal DA, more so than cortical DA. The D2 receptor class is predominantly expressed in striatum relative to prefrontal cortex (Camps, Cortes, Gueye, Probst, & Palacios, 1989; Gee et al., 2012; Jenni, Larkin, & Floresco, 2017; Trantham-Davidson, Neely, Lavin, & Seamans, 2004), making striatal influence more likely than cortical influence. However, both D1 and D2 receptors are expressed in prefrontal cortex, and they appear to underlie similar manifest functions as striatal D1 and D2 pathways during active maintenance and selective gating. The findings reported here are largely compatible with the dual-state theory (Durstewitz & Seamans, 2008), which suggests that the ratio of D1 and D2 activation in the prefrontal cortex (rather than in thalamo-striatal circuitry) modulates the balance between stable and flexible representations. Despite these broad similarities, striatal D2 functions are specifically dissociated from prefrontal cortex D2 by the selective suppression of distractors (Frank, 2005), whereas cortical D2 effects may predict less stable WM states overall (Durstewitz & Seamans, 2008). In sum, the PBWM model of striatal D2 effects on VSWM remains the most parsimonious account of the findings reported here.

Implications

Disturbances of dopaminergic functioning underlay a variety of disease states including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Dougherty et al., 1999), schizophrenia (Abi-Dargham et al., 2000), addiction (Dalley, Everitt, & Robbins, 2011), and Parkinson’s disease (Cools et al., 2010; Moustafa et al., 2008). The PBWM framework extends to cognition earlier D1–D2 theories of motor function (Moustafa et al., 2008), while cognitive difficulties for Parkinson’s patients are being increasingly appreciated. The present work extends PBWM framework to VSWM. Pharmacological experiments such as the present work can advance our understanding of the dopaminergic bases for such disease states, especially when guided by computational theories such as PBWM.

It has become clear that individual differences in baseline DA synthesis must be taken into account to advance our understanding of how DA supports cognition, affect, and behavior (Cools & D’Esposito, 2011). The current and previous studies have demonstrated that WM span is a sensitive measure in this respect. However, comparisons across studies are fraught with uncertainty, concerning precisely how high versus low span individuals react to a dopaminergic agent in a particular task. This is because the high (low) span individuals in a given study may not be truly high (low) span in the population. For example, in the present study, we determined that lower WM span individuals in the study sample really corresponded to upper midspan individuals, in reference to a published normative distribution (Redick et al., 2012). Unfortunately, such information has been lacking in previous D2-receptor agonist experiments which have taken individual differences in WM span into account, introducing uncertainty about where the individuals were located at the population-level distribution. Therefore, to advance the field with respect to accounting for individual differences, and to facilitate comparison across such studies, it would be advantageous if sample WM span distributions were described in reference to published normative distributions (e.g., Redick et al., 2012), as in the present work.

Conclusion

Through pharmacological manipulation, the present experiment showed that VSWM distractor filtering is supported by DA-driven striatal activation/inhibition of cortex, in line with predictions from the PBWM computational theory. The D2-receptor agonist affected interference from distractors, depending on individual differences in baseline DA (WM span). Thus the experiment makes novel contributions to better general understanding the striatal mechanisms supporting WM, both in health and disease.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) 1125788 and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) 1P20GM109089–01A1.

References

- Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y,… & Laruelle M (2000). Increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 14, 8104–8109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awh E, Barton B, & Vogel EK (2007). Visual working memory represents a fixed number of items regardless of complexity. Psychological Science, 18, 622–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley AD, & Hitch GJ (1974). Working memory In Bower GA (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 8, pp. 47–89). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baier B, Karnath H, Dietrich M, Birklein F, Heinze C, & Muller G (2010). Keeping memory clear and stable—The contribution of human basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex to working memory. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 9788–9792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller BM, Molitch ME, Vance ML, Cannistraro KB, Davis KR, Simons J,… Klibanski A (1996). Treatment of prolactin-secreting macroadenomas with the once-weekly dopamine agonist cabergoline. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental, 81, 2338–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainerd DH (1997). The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spatial Vision, 10,433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusa L, Pavino V, Massimetti MC, Bove R, Iani C, & Stanzione P (2013). The effect of dopamine agonists on cognitive functions in non-demented early-mild Parkinson’s disease patients. Functional Neurology, 28, 13–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M, Cortes R, Gueye B, Probst A, & Palacios JM (1989). Dopamine receptors in the human brain: Autoradiographic distribution of D sites. Neuroscience, 28, 275–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh JF, Masters SE, Bath K, & Frank MJ (2014). Conflict acts as an implicit cost in reinforcement learning. Nature Communications, 5 10.1038/ncomms6394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatham CH, Frank MJ, & Badre D (2014). Corticostriatal output gating during selection from working memory. Neuron, 4, 930–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analyses for the behavioral sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Colzato LS, Slagter HA, de Rover M, & Hommel B (2011). Dopamine and the management of attentional resources: Genetic markers of striatal D2 dopamine predict individual differences in the attentional blink. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23, 3576–3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R (2008). Role of dopamine in the motivational and cognitive control of behavior. Neuroscientist, 14, 381–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R (2011). Dopaminergic control of the striatum for high-level cognition. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 21, 402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, & D’Esposito M (2011). Inverted U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Frank MJ, Gibbs SE, Miyakawa A, Jagust W, & D’Esposito M (2009). Striatal dopamine predicts outcome-specific reversal learning and its sensitivity to dopaminergic drug administration. The Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 1538–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Gibbs SE, Miyakawa A, Jagust W, & D’Esposito M (2008). Working memory capacity predicts dopamine synthesis capacity in the human striatum. Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 1208–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cools R, Miyakawa A, Sheridan M, & D’Esposito M (2010). Enhanced frontal function in Parkinson’s disease. Brain, 133, 225–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan N (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24, 87–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Everitt BJ, & Robbins TW (2011). Impulsivity, compulsivity, and top-down cognitive control. Neuron, 69, 680–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DD, Bonab AA, Spencer TJ, Rauch SL, Madras BK, & Fischman AJ (1999). Dopamine transporter density in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The Lancet, 354, 2132–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durstewitz D, & Seamans JK (2008). The dual-state theory of pre-frontal cortex dopamine function with relevance to catechol-o-methyltransferase genotypes and schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 64, 739–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle RW, Tuholski SW, Laughlin JE, & Conway ARA (1999). Working memory, short-term memory, and general fluid intelligence: A latent variable approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 128, 309–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon SJ, van der Schaaf ME, ter Huurne N, & Cools R (2017). The neurocognitive cost of enhancing cognition with methylphenidate: Improved distractor resistance but impaired updating. The Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 29, 652–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon SJ, Zokaei N, & Husain M (2016). Causes and consequences of limitations in visual working memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369, 40–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon SJ, Zokaei N, Norbury A, Manohar SG, & Husain M (2017). Dopamine alters the fidelity of working memory representations according to attentional demands. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 29, 728–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fariello RG (1998). Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic features of cabergoline. Drugs,55(Suppl.), 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ (2005). Dynamic dopamine modulation in the basal ganglia: A neurocomputational account of cognitive deficits in medicated and non-medicated parkinsonism. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 51–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, & Fossella JA (2011). Neurogenetics and pharmacology of learning, motivation, and cognition. Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews, 36, 133–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Loughry B, & O’Reilly RC (2001). Interactions between prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia in working memory: A computational model. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 1, 137–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, & O’Reilly RC (2006). A mechanistic account of striatal dopamine function in human cognition: Psychopharmacological studies with cabergoline and haloperidol. Behavioral Neuroscience, 120, 497–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MJ, Santamaria A, O’Reilly RC, & Wilcutt E (2007). Testing computational models of dopamine and noradrenaline dys-function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32, 1583–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K, Awh E, & Vogel EK (2010). Discrete capacity limits in visual working memory. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 20, 177–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee S, Ellwood I, Patel T, Luongo F, Deiserroth K, & Sohal VS (2012). Synaptic activity unmasks dopamine D2 receptor modulation of a specific class of Layer V pyramidal neurons in prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 32, 4959–4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach M, Double K, Arzberger T, Leblhuber F, Tatschner T, & Riederer P (2003). Dopamine receptor agonists in current clinical use: Comparative dopamine receptor binding profiles defined in the human striatum. Journal of Neural Transmission, 110, 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs SEB, & D’Esposito M (2005). Individual capacity differences predict working memory performance and prefrontal activity following dopamine receptor stimulation. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 5, 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazy TE, Frank MJ, & O’Reilly RC (2007). Towards an executive without a homunculus: Computational models of the prefrontal cortex/basal ganglia system. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa K, & Kojima M (2001). Pharmacological effects of cabergoline against parkinsonism. Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi, 117, 395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilkowska M, & Engle RW (2010). Trait and state differences in working memory capacity In Gruszka A, Matthews G, & Szymura B (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in cognition: Attention, memory, and executive control (pp 295–319). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jenni NL, Larkin JD, & Floresco SB (2017). Prefrontal dopamine D1 and D2 receptors regulate dissociable aspects of decision-making via distinct ventral striatal and amygdalar circuits. The Journal of Neuroscience, 37, 6200–6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, & Engle RW (2002). The role of prefrontal cortex in working memory capacity, executive attention, and general fluid intelligence: An individual-differences perspective. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9, 637–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimberg DY, D’Esposito M, & Farah MJ (1997). Effects of bromocriptine on human subjects depend on working memory capacity. Neuroreport, 8, 3581–3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau SM, Lal R, O’Neil JP, Baker S, & Jagust WJ (2009). Striatal dopamine and working memory. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, & Vogel EK (1997). The capacity of visual working memory for features and conjunctions. Nature, 390, 279–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, & Vogel EK (2013). Visual working memory capacity: From psychophysics and neurobiology to individual differences. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17, 391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JM, Husain M, & Bays PM (2014). Changing concepts of working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 347–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNab F, & Klingberg T (2008). Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia control access to working memory. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Rosenthal R, & Rubin DB (1992). Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 172–175. [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Maoffiss L, Didra C, Audino V, Bontin J, & Newman-Tancredi A (2002). Differential actions of antiparkinson agents at multiple classes of monoaminergic receptor: I. A multivariate analysis of the binding profiles of 14 drugs at 21 native and cloned human receptor subtypes. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 303, 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa AA, Sherman SJ, & Frank MJ (2008). A dopaminergic basis for working memory, learning and attentional shifting in parkinsonism. Neuropsychologia, 46, 3144–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar MR, Helmers J, & Frank MJ (2017). Chunking as a rational strategy for lossy data compression in visual working memory tasks. Retrieved from http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/01/06/098939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly RC, & Frank MJ (2006). Making working memory work: A computational model of learning in the frontal cortex and basal ganglia. Neural Computation, 18, 283–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redick TS, Broadway JM, Meier ME, Kuriakose PS, Unsworth N, Kane MJ, & Engle RW (2012). Measuring working memory capacity with automated complex span tasks. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 164–171. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rouder JN, Morey RD, Morey CC, & Cowan N (2011). How to measure working memory capacity in the change detection paradigm. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider W, Eschman A, & Zuccolotto A (2002). E-Prime user’s guide. Pittsburgh, PA: Psychology Software Tools. [Google Scholar]

- Slagter HA, Tomer R, Christian BT, Fox AS, Colzato LS, King CR,… Davidson RJ (2012). PET evidence for a role for striatal dopamine in the attentional blink: Functional implications. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 24, 1932–1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocchi F, Vacca L, Berardelli A, Onofj M, Manfredi M, & Ruggieri S (2003). Dual dopamine agonist treatment in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, 250, 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trantham-Davidson H, Neely LC, Lavin A, & Seamans JK (2004). Mechanisms underlying differential D1 versus D2 dopamine receptor regulation of inhibition in prefrontal cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 10652–10659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth N, & Engle RW (2007). On the division of short-term and working memory: An examination of simple and complex span and their relation to higher order abilities. Psychological Bulletin, 133, 1038–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth N, Heitz RP, Schrock JC, & Engle RW (2005). An automated version of the operation span task. Behavior Research Methods, 37, 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel EK, McCollough AW, & Machizawa MG (2005). Neural measures reveal individual differences in controlling access to working memory. Nature, 438, 500–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, & Luck SJ (2008). Feature-based attention modulates feedforward visual processing. Nature Neuroscience, 12, 24–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]