SUMMARY

Background

Acute graft-versus-host-disease (aGVHD) after nonmyeloablative human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched unrelated donor allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. The trial evaluated the efficacy of adding sirolimus to cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil GVHD prophylaxis in preventing aGVHD.

Methods

The trial was a 2-arm multicenter randomized phase III trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ) comparing cyclosporine (day −3 to +96 and taper to day +150) and mycophenolate mofetil (day 0 to +150 and taper to day 180) (standard arm; n=77) with cyclosporine (same dosing as standard arm), mycophenolate mofetil (day 0 to +40), and sirolimus (day −3 to +150 and taper to day +180) (triple-drug arm; n=91). The primary endpoint was grade II-IV aGVHD at 100 days post-transplant. Patients were randomized by the coordinating centre according to a sequential algorithm stratified on study site. Patients and physicians were not blinded to treatment assignment. The Data and Safety Monitoring Board prematurely closed the study when detecting a significant survival advantage in the triple-drug arm in a prespecified interim analysis for futility.

Findings

Day +100 grade II-IV aGVHD was lower in the triple-drug arm vs. the standard arm (26% vs 52%, p=0.001), translating into lower non-relapse mortality (4% vs 16%, p=0.02), higher overall survival (86% vs 70%, p=0.04) and higher progression-free survival (77% vs 64%, p=0.05) at 1 year. We observed no difference in the incidence of chronic GVHD or relapse. The most common grade 3 or higher toxicity reported was pulmonary in 19 (11%) of patients.

Interpretation

Adding sirolimus to cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil resulted in a significantly lower incidence of acute GVHD. Based on these results, the combination of cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus has become the standard GVHD prophylaxis after nonmyeloablative conditioning for HLA-matched unrelated HCT at Fred Hutch.

INTRODUCTION

We developed a minimum-intensity nonmyeloablative regimen consisting of fludarabine and low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) to condition older or medically-infirm patients with hematologic malignancies for hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched related or unrelated donors.1,2 This transplant approach is well tolerated, can be conducted in the outpatient setting, and relies almost entirely on graft-vs.-tumor (GVT) effects for eradicating the underlying malignancies. Depending on disease and disease burden, and the extent of comorbidities, 5-year survival rates have ranged from 25% to 60%.3 The overall five-year non-relapse mortality (NRM) among the first 1,092 patients was 24.5%, which, in large part, was associated with or preceded by GVHD.3 In order to enable engraftment and control graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD), the standard postgrafting immunosuppression after nonmyeloablative conditioning combines a calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil, which exert their immunosuppressive effects by selectively blocking cytokine transcription and by inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation. Our studies showed that with this approach acute GVHD conveyed no significant GVT effect. Since acute GVHD rates were highest among unrelated recipients, we chose the unrelated HCT setting for attempts to improve acute GVHD prevention by adding sirolimus as a third immunosuppressive agent.3 The rationale behind adding sirolimus was that its mode of action is different from that of calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil, namely by blocking cytokine-mediated signal transduction pathways through inhibiting the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR).

In a Phase II trial that involved 208 unrelated recipients, we compared three different post-transplant immunosuppressive regimens that were based upon a backbone of different calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil schedules, one of which was a triple-drug regimen that included an 80-day course of sirolimus.4 Results showed significantly less grade II acute GVHD, lower use of systemic steroids, and a reduction in risk of CMV reactivation compared to the standard double-drug regimen without an increasing the risk of relapse nor differences in the incidence of chronic GVHD.

In order to confirm these findings, we conducted the current 2-arm multicenter phase III trial in which unrelated HCT recipients were randomized between the standard GVHD prophylaxis consisting of cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil and a triple-drug combination of cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, and sirolimus. However, given the late development of acute GVHD following discontinuation of sirolimus on day 80 in the original study, we attempted to further exploit the immunomodulatory effects of the drug and extended its period of administration to 180 days in the current trial. The trial was halted by the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) after 168 patients had been randomized, short of the planned accrual goal of 300 patients.

METHODS

Study Design and participants

The randomized phase III trial included 9 HCT centers (appendix, p.7). The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Fred Hutch) acted as coordinating center. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at Fred Hutch and each of the collaborating centers. All patients signed IRB-approved consent forms. The study was in accord with the CONSORT 2010 statement (Figure 1) and registered with clinicalTrials.gov (). The protocol is available for viewing at clinicalTrials.gov.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

The initial study was designed as a 3-arm phase II trial, the standard arm of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine, a triple arm with sirolimus added to mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine, and a third arm of cyclosporine and sirolimus. However, an external review board recommended a 2-arm definitive phase III design. Before this change was implemented, six patients had been enrolled in the closed cyclosporine and sirolimus arm. These patients have not been included in the analyses.

Included in this study were patients with advanced hematological malignancies (Table 1) treatable by allogeneic HCT. Donors were unrelated, high-resolution matched for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 and -DQB1 at the allele level (n=160) or mismatched at no more than a single allele disparity for either HLA-A, -B, or -C (n=8). Patients and donors were not routinely typed for HLA-DP at all centers. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor mobilized blood cells were the sole graft source.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, according to study arm

| Characteristic | Standard Arm (n= 77) | Triple-drug Arm (n= 91) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient age, median (IQR), years | 61 (53–67) | 63 (58–68) |

| Male patient, n (%) | 50 (65) | 63 (69) |

| Donor age, median IQR), years | 26 (22–34) | 25 (22–35) |

| Single allele HLA mismatch, n (%) | 4 (5) | 4 (4) |

| Sex of patient / donor, n (%) | ||

| Male / Female | 23 (30) | 12 (13) |

| Other combinations, | 54 (70) | 79 (87) |

| Prior CMV infection of patient/donor, n (%) | ||

| Negative/negative | 16 (21) | 37 (41) |

| Negative/positive | 8 (10) | 8 (9) |

| Positive/negative | 27 (35) | 28 (31) |

| Positive/positive | 26 (34) | 17 (19) |

| Prior high-dose HCT, n (%) | ||

| Autologous | 19 (25) | 13 (14) |

| Allogeneic | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Time from first transplant, median (IQR), days | 297 (93–1188) | 94 (75–552) |

| Number of previous regimens, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) |

| Diagnoses, n (%) | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 25 (32) | 41 (45) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 14 (18) | 15 (16) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 6 (8) | 9 (10) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 12 (16) | 15 (16) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 9 (12) | 5 (5) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 2 (3) | 0 |

| Multiple myeloma | 8 (10) | 5 (4) |

| Relapse risk (Kahl29), n (%) | ||

| Low | 20 (26) | 30 (33) |

| Standard | 47 (61) | 46 (51) |

| High | 10 (13) | 15 (16) |

| HCT comorbidity index, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 12 (16) | 13 (14) |

| 1,2 | 24 (32) | 31 (34) |

| 3+ | 40 (53) | 47 (52) |

| Donor recipient ABO match, n (%) | ||

| Match | 41 (53) | 44 (48) |

| Major mismatch | 15 (19) | 28 (31) |

| Minor mismatch | 19 (25) | 18 (20) |

| Incomplete data | 2 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Peripheral blood stem cell dose | ||

| CD34+ cells × 106 / kg, median (IQR) | 8.0 (5.6–10.4) | 8.0 (6.0–10.7) |

| CD3+ cells × 108 / kg, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.3–4.2) | 2.8 (2.2–3.6) |

Eligibility criteria and patient evaluations are described in the supplementary Appendix, p.2.

The protocol was opened in November 1, 2010. The accrual goal was 300 patients, based on 150 patients per arm providing 94% power for a difference of 20% (and 74% power for a difference of 15%) in the primary endpoint, at the 2-sided 0.05 level of significance. However, the protocol closed prematurely, by recommendation of the DSMB, on July 27, 2016 after accruing 168 patients. Results were analyzed as of July 1, 2018.

Randomisation

Patients were allocated to the two study arms by an adaptive randomization scheme stratified by transplant center.5 Patients were enrolled by study staff at participating sites after confirming eligibility with the coordinating center. Randomization for all sites was performed by the Clinical Statistics department at Fred Hutch. Patients and physicians were not blinded as to treatment assignment. As noted in Figure 1, six patients failed to proceed to transplant and were therefore unevaluable for the primary endpoint. All six were withdrawn prior to receiving protocol intervention. All transplanted patients received their assigned intervention.

Procedures

Patients were prepared for HCT with fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day) on days −4, −3, and −2 before receiving 2 Gy TBI (n=76) on the day of HCT (day 0). Patients who had no previous myelosuppressive chemotherapy or none within 3–6 months before entering the trial (n=87) or who had a previous allogeneic HCT with >5% CD3 chimerism from the first donor (n=4) were treated with 3 Gy TBI. Peripheral blood stem cell donor grafts were collected from donors by NMDP standards after 5 days of subcutaneously administered granulocyte colony stimulating factor at a dose of approximately 10 µg/kg. Patients were randomized between two immunosuppressive GVHD prophylaxis regimens, herein referred to as the “standard arm” and “triple-drug arm”. In both arms, 5.0 mg/kg of cyclosporine was administered orally twice daily from day −3 and, in the absence of GVHD tapered from day +96 through on day +150. In the standard arm, cyclosporine trough levels were targeted at 400 ng/ml for the first 28 days and thereafter between 150–350 ng/ml until taper. In the triple-drug arm, cyclosporine trough levels were targeted at 350 ng/ml for the first 28 days and thereafter at 120–300 ng/ml until taper. In the standard arm, 15 mg/kg of mycophenolate mofetil was given orally three times daily. from day 0 until day 30, then twice daily until day 150, and, in the absence of GVHD, tapered off by day 180. In the triple-drug arm, mycophenolate mofetil doses were the same as in the standard arm, but the drug was discontinued on day 40. Sirolimus was started at day −3 at 2 mg orally once daily. and adjusted to maintain trough levels between 3–12 ng/ml through day 150 followed by taper through day 180 in the absence of GVHD. Supportive care, antibiotic prophylaxis and detection and treatment of CMV reactivation were conducted according to local institutional guidelines. Diagnosis, clinical grading, and treatment of acute and chronic GVHD were performed by local investigators according to established criteria.6,7

Outcomes

The primary objective of the trial was to compare the effectiveness of the triple-drug regimen in reducing the risk of grade II-IV acute GVHD after HLA-matched unrelated nonmyeloablative conditioning HCT to that of the standard two-drug regimen. Secondary objectives included NRM, overall survival, progression-free survival (PFS), and grade III-IV acute and chronic extensive GVHD. Exploratory outcomes were engraftment, acute GVHD organ involvement, incidence of corticosteroid treatment, and infections.

Statistics

Overall survival and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Cumulative incidence frequencies of endpoints with competing risks were estimated by methods previously described.8 Death was treated as a competing risk for all endpoints; relapse was treated as a competing risk for NRM, acute GVHD, and withdrawal of immunosuppression. GHVD was censored for DLI. Cox regression was used for all time-to-event endpoints, with competing risks analysis based on event-specific hazard ratios. No significant departures from proportional hazards were noted for any endpoint, based on a test of interaction of treatment with (log) time. There were no missing data among primary and secondary endpoints and characteristics in Table 1. All cited p-values for time-to-event endpoints refer to hazard ratio analyses over the entire period of follow-up. Comparisons of GVHD organ stage and toxicity proportions were performed by chi-squared test. Comparisons of donor chimerism proportions and peripheral blood counts were performed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All p-values are 2-sided and without adjustment for multiple comparisons. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS Version 8 (Cary, NC).

Role of the Funding Source

The funder of the study (National Institute of Health) had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. BMS, BK, BES, DGM and RS had access to the raw data.

RESULTS

Seventy-seven patients were randomized into the standard arm and 91 into the triple-drug arm. One patient in the triple arm was excluded from the analysis because the HCT was aborted during conditioning due to medical complications Pre-transplant demographics were fairly evenly distributed among arms, except for prior transplants, where 23 (30%) patients in the standard arm had 1 prior HCT compared to 13 (14%) in the sirolimus arm (Table 1). Prior to entering the trial 30 patients (19%) had 1 autologous high-dose HCT, while 2 patients with multiple myeloma had 2 and 3 prior autologous HCT, respectively. Eight of the 13 patients with multiple myeloma (62%) had a prior autologous high-dose HCT. Median follow-up of surviving patients at the time of analysis was 48 months [interquartile range (IQR) 31–60 months, range 6–84 months].

Except for two rejections in the standard arm, all patients had sustained engraftment. One of the two had failed a previous allogeneic HCT for CLL and rejected the second graft at day +28. The other had AML-CR2 and rejected the graft at day 158. Near complete median granulocyte and NK cell donor chimerism was achieved in both arms by day +28 [triple-drug arm, 95% (IQR 94–100%) vs. standard arm, 98% (IQR 95–100%); p=0.12; and 97% (IQR 94–100%); vs. standard arm, 95% (IQR 88–100%); p=0.20, respectively (appendix, p. 4). Median donor T-cell chimerism was lower in the triple-drug arm on day +28 [79% (IQR 59–89%) vs. 84% (IQR 75–95%); p=0.030] (appendix, p. 4). Among patients surviving to day +100 median donor T-cell chimerism at the last available measurement was 89% (IQR 72–94%) and 93% (IQR 76–99%) (p=0.026), and 24% (20 of 84) and 41% (28 of 68) of patients had more than 95% donor T-cell chimerism (p=0.022) in the triple-drug and standard arms, respectively. Absolute neutrophil count and platelet count nadirs were similar in the two arms (Appendix, p. 8), while median number of days with absolute neutrophil count < 500 cells/µL was higher in the triple-drug arm [13, IQR 8–15 days) as compared to the standard arm (10, IQR 5–14 days) (p=0.033).

Four standard arm patients received DLI for low donor chimerism without developing subsequent GVHD. Three triple-drug arm patients received DLI, 2 for relapsed AML and NHL, and 1 for low donor chimerism. The latter patient developed acute GVHD after the second DLI. No patients were on immunosuppressive treatment at the time of DLI.

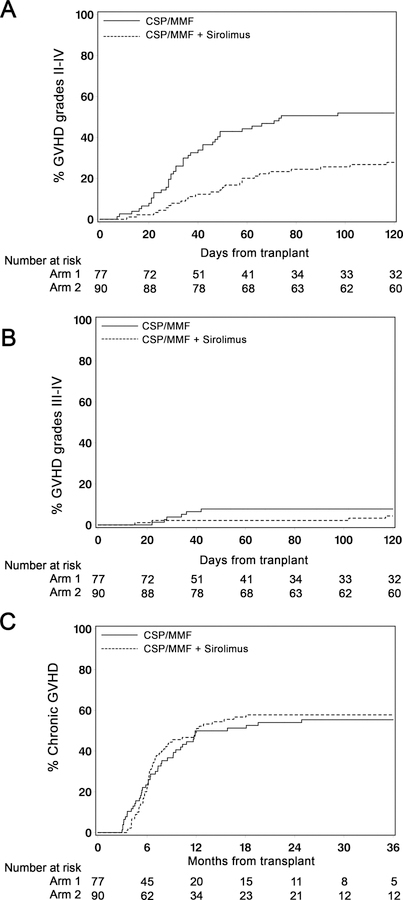

The cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD at day +100 was 26% (95% CI 17–35%) in the triple-drug arm compared to 52% (95% CI 41–63%) in the standard arm [HR 0.45 (95% CI 0.28–0.73)]; (p=0.0013) (Figure 2A). Three patients developed acute GVHD after day 100. Corresponding values for grade III-IV acute GVHD were 2% (95% CI 0–5%) in the triple-drug arm versus 8% (95% CI 2–14%) in the standard arm [HR 0.55 (95% CI 0.16–1.96); (p=0.36)]; (Figure 2B). Consistent with the difference in acute GVHD, the cumulative incidence of systemic corticosteroid treatment up to 1 year was 26% (95% CI 20–38%) in the triple arm compared to 64% (95% CI 53–74%) in the standard arm [HR 0.33 (95% CI 0.20–0.52); p<0.0001].

Figure 2. Graft-versus-host disease.

Cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD(A), grade III-IV acute GVHD (B) and chronic GVHD (C) among patients in the triple-drug arm (n=90) and in the standard arm (n=77). NRM among patients with chronic GVHD in the triple-drug arm (n=50) and standard arm (n=41) (D).

The proportions of patients with acute GVHD of skin, gut and liver in the triple versus standard arms were 18% versus 55% (p<0.0001), 28% versus 38% (p=0.17) and 1% versus 2% (p=0.65), respectively. Acute GVHD organ stages are summarized in the appendix, p. 9. Cumulative incidences of chronic GVHD at 1 year were comparable [triple-drug arm 49% (95% CI 39–59%); standard arm 50% (95% CI 39–61%)] (Figure 2C) as were sites of chronic GVHD. Patients affected by chronic GVHD in the triple arm had a trend to lower NRM compared to those in the standard arm (HR 0.45 [95% CI 0.19–1.10] p=0.080; see appendix, p. 5). Chronic GVHD was preceded by acute GVHD (grades 2–4) in 27 of 42 patients in the standard arm (64%) and in 15 of 53 patients in the triple arm (28%). After 3 years, the cumulative incidence of being off immunosuppressive therapy was 17% (95% CI 9–25%) in the triple-drug arm and 15% (95% CI 7–23%) in the standard arm [HR 1.05 (95% CI 0.52–2.12)]; p=0.90).

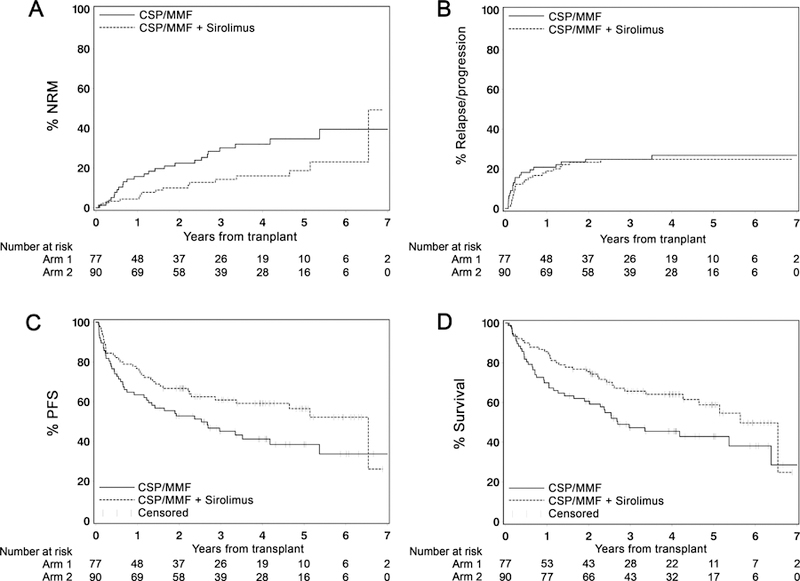

No differences were observed in the overall incidence of non-hematopoietic toxicities by day 100 post-transplant [triple-drug arm, 25% (95% CI 16–34%); standard arm, 34% (95% CI 24–45%); HR 0.84 (95% CI 0.49–1.44); p=0.52] (Table 2). Four patients in the triple-drug arm experienced hypertriglyceridemia (CTCAE grade ≥3) and one patient had microangiopathy (CTCAE grade 3). No patient experienced veno-occlusive disease of the liver. One-year cumulative incidences of bacterial [45% (95% CI 35–56%) versus 37% (95% CI 26–48%); HR 01.05 (95% CI 0.69–1.62); p=0.81], fungal [12% (95% CI 6–19%) versus 18% (95% CI 9–26%); HR 0.77 (95% CI 0.38–1.58); p=0.48], and non-CMV viral infections [29% (95% CI 19–38%) versus 41% (95% CI 29–52%); HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.41–1.01); p=0.056] at 1 year were comparable among triple-drug versus standard arm patients. Among patients who were CMV-positive or had CMV-positive donors (triple-drug arm, 53 (59%); standard arm, 61 (79%)) (Table 1), the cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation or CMV infection up to 1 year after transplantation was significantly lower in the triple-drug arm [38% (95% CI 25–51%) versus 69% (95% CI 57–81); HR 0.35 (95% CI 0.21–0.60); p=0.0001] (appendix, p. 6). The cumulative incidences of NRM were 3% (95% CI 0–7%) at day +100 in both arms and increased to 4% (95% CI 0–9%) and 16% (95% CI 8–24%) in the triple-drug arm and 16% (95% CI 8–24%) and 32% (95% CI 21–43%) in the standard arm after 1 and 4 years respectively [HR 0.48 (95% CI 0.26–0.90), p=0.021] (Figure 3A). Overall, 41 (triple-drug arm, n=16; standard arm, n=25) patients experienced NRM, most commonly related to GVHD with or without infection (n=8 versus n=13, respectively). In the triple drug arm 2 patients died of infection compared to 6 in the standard arm. In the triple-drug arm 4 patients experienced NRM unrelated to GVHD or infection [cardiomyopathy (n=1), lung embolism (n=1), pulmonary complications (n=1) and multi-organ failure (n=1), compared to 6 patients in the standard arm [cardiomyopathy (n=1), renal failure (n=1), multi-organ failure (n=1), brain hemorrhage (n=1), secondary malignancy (n=1) and unknown cause (n=1)].

Table 2.

Toxicities in the treatment arms according to the Common Toxicity Criteria Version 4.0.

| Standard arm (n=77) |

Triple-drug arm (n=90) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum grade | Maximum grade | |||

| Toxicity (no.) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Renal and urinary disorder | 6 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Hepatic | 9 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiac | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pulmonary | 5 | 4** | 5 | 5 |

| Coagulation | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Blood and lymphatic system | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurology | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Dermatology | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Comparison of proportion of patients with grade 3–4 toxicity between arms

Includes one patient with grade 5 toxicity

Figure 3. Survival and progression.

Cumulative incidence NRM (A), relapse/progression (B), PFS (C) and overall survival (D) among patients in the triple-drug arm (n=90) and in the standard arm (n=77). Tic marks indicate the most recent follow-up among surviving patients.

No difference in relapse/progression incidence was observed between arms at 1 year after HCT [triple-drug arm, 19% (95% CI, 11%–27%); standard arm, 21% (95% CI, 12–30%)] or at 4 years [triple-drug arm, 25% (95% CI, 16%–34%); standard arm, 27% (95% CI, 17%–37%)] [HR 0.85 (95% CI, 0.47–1.56); p=0.61] (Figure 3B). PFS at 1 year in the triple-drug and standard drug arms was 77% (95% CI, 68%–85%) and 64% (95% CI, 53%–74%), respectively, and at 4 years was 59% (95% CI, 49%–70%) and 41% (95% CI, 30%–53%), respectively, [HR 0.64 (95% CI 0.42–0.99), p=0.045] (Figure 3C). OS at 1 year in the triple-drug and standard drug arms was 86% (95% CI, 78%–93%) and 70% (95% CI, 60%–80%), respectively, and at 4 years was 64% (95% CI, 54%–75%) and 46% (95% CI, 34%–5%), respectively, [HR 0.62 (95% CI, 0.40–0.97), p=0.035] (Figure 3D).

We noted four factors in Table 1 that by chance were imbalanced by more than 10 percentage points between arms and could plausibly be related to reported outcomes: female to male sex mismatch, patient/donor CMV seropositivity, prior transplant, and Kahl risk group. Adjustment for these factors did not materially alter hazard ratio results compared to unadjusted results (appendix, p.10) and did not alter any conclusions derived from the unadjusted results.

DISCUSSION

The current phase III trial design was based on results of a preceding phase II trial and sought to definitively test the hypothesis that a triple-drug combination of mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine and sirolimus would control acute GVHD significantly better than the standard combination of mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine. If the primary study aim was met, we expected improvements in the secondary endpoints of NRM, overall survival, and PFS.

The DSMB halted the trial early after 168 of the planned 300 patients had been enrolled because they saw a significant survival advantage among patients in the triple-drug arm. Sixty-three percent of the patients had been enrolled at the Fred Hutch. The root cause for the impressive improvement in overall survival was likely the significant, 26% reduction in the primary study endpoint, acute GVHD, given the well-established high mortality associated with acute GVHD. Importantly, the reduced incidence of acute GVHD was not offset by an increase in relapse or progression. The latter finding was consistent with previous data showing no significant association between acute GVHD and GVT effects in this HCT setting.3 The 2% incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD was gratifyingly low in the triple-drug arm but not significantly different from the 8% observed in the standard arm which, in turn, was comparable to our previous experience.4 The premature closure of the trial precluded more definitive assessment of differences in grade III-IV acute GVHD between the two study arms. The generally high incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD historically among Fred Hutch patients is likely due to the aggressive use of endoscopy in an attempt at diagnosing and treating gut GVHD early.9 Of note, the 2% incidence of grade III-IV acute GVHD in current triple-drug patients is lower than the 13% seen in previously reported triple-drug cohort.4 We believe this is due to the extension of sirolimus administration from the previous 80 days to the current 180 days. While the incidence of chronic GVHD was similar in the two arms and comparable to previous observations among unrelated recipients,4,10 triple-drug patients affected by chronic GVHD had a trend to lessened NRM suggesting less severe chronic GVHD manifestation compared to patients in the standard arm.

Overall, the addition of sirolimus to calcineurin inhibitor and mycophenolate mofetil was safe and well tolerated. After nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine plus 2 Gy TBI, veno-occlusive disease has nearly never been observed. Adverse events described for sirolimus after high dose conditioning such as hypertriglyceridemia and transplantation-associated microangiopathy were rare. In this setting there is no evidence that sirolimus increases the risk of developing TA-TMA. The generally low incidence of TA-TMA in our study is likely due to attending physicians’ attention to TA-TMA risk factors, such as CNI/SIR levels, in patients entered on the protocol. While bacterial and fungal infection rates were similar in the two trial arms, CMV reactivation was significantly lower in the triple-drug arm. This could have been due to specific antiviral activity of sirolimus, to the reduced incidence of acute GVHD resulting in less steroid use, or a combination of these factors.11

Although a significant difference was observed for the primary endpoint, the trial was limited by its premature closure which precluded definitive assessment of differences in grade III-IV acute GVHD. An imbalance in some pre-transplant demographics was observed. However, adjustment for these factors did not materially alter hazard ratio results compared to unadjusted results.

While sirolimus has been investigated in allogeneic HCT for almost two decades, it has yet to move beyond clinical trials and be widely used as standard GVHD prophylaxis. Sirolimus added to tacrolimus or to a combination of low-dose methotrexate or anti-thymocyte globulin has been focus of several prospective single arm tr8ials. The results are difficult to compare due to heterogeneity in study populations and treatment regimens. Observed rates of grade II-IV acute GVHD and chronic GVHD ranged from 16 to 77% and 32 to 77%, respectively.12–22 Only three randomized trials have been published, all involving myeloablative preparative regimens before HCT, in which sirolimus was added to tacrolimus in lieu of or in addition to methotrexate. One of these trials showed a significant reduction in both grade II-IV acute GVHD and moderate to severe chronic GVHD without a concurrent reduction in NRM.23 A second trial showed a reduction in grade II-IV acute GVHD without a concurrent reduction in NRM.24 A third trial reported no differences in acute or chronic GVHD.25 None of the 3 trials showed improvements in overall survival.

A study among patients given reduced-intensity preparative regimens, Armand et al. randomized 139 patients to receive either a triple combination of calcineurin inhibitor, methotrexate and sirolimus or double combinations of calcineurin inhibitor with mycophenolate mofetil or calcineurin inhibitor with methotrexate. The triple combination resulted in a significant reduction in grade II-IV acute GVHD (9% vs 25%), however, without showing differences in chronic GVHD or in overall survival.26

More recently, GVHD prophylaxis with sirolimus has been combined with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide in patients with hematologic malignancies given myeloablative conditioning before HLA-mismatched or HLA-matched unrelated HCT. Results were promising with 23% to 25% cumulative incidences of grade II-IV acute GVHD at days 100 and 180 post-transplantation, and 13% to 16% chronic GVHD, 6% to 14% NRM, and 35% to 36% relapse at 1 to 2 years after transplantation.27,28

To our knowledge the current study is the first phase III trial showing that combining sirolimus, cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil significantly improves overall survival and PFS by reducing the rates of grade II-IV acute GVHD and NRM without increasing the risk of relapse, thereby setting a new standard for GVHD prevention after unrelated HCT with nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens.

Further studies are needed to establish whether these promising results with GVHD prophylaxis with calcineurin inhibitor, mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus may translate into other donor-recipient settings or after other more intense conditioning regimens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in the clinical trial. They also thank their colleagues on the transplant services, the research staff, clinical staff, and the referring physicians at all the participating sites. We also thank Dr. Derek Stirewalt and the rest of the DSMB members for their review of the conduct of the trial. We greatly appreciate Helen Crawford’s assistance with manuscript and figure preparation.

Grant support: Research funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, grants, CA018029, CA078902 and CA015704 from the National Cancer Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health nor its subsidiary Institutes.

Funding Funded by The National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Brenda M. Sandmaier, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington.

Brian Kornblit, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Department of Hematology, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Barry E. Storer, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington

Gitte Olesen, Department of Hematology, Aarhus Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark.

Michael B. Maris, Colorado Blood Cancer Institute, Denver, Colorado

Amelia A. Langston, Winship Cancer institute of Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia

Jonathan A. Gutman, Division of Hematology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, Colorado

Soeren L. Petersen, Department of Hematology, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

Thomas R. Chauncey, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle, Washington

Wolfgang A. Bethge, Department of Hematology and Oncology, Eberhard Karls University, Tuebingen, Germany

Michael A. Pulsipher, Division of Hematology Oncology/Blood and Marrow Transplant, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, USC Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California

Ann E. Woolfrey, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

Marco Mielcarek, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Paul J. Martin, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Fred R. Appelbaum, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Mary E.D. Flowers, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington

David G. Maloney, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

Rainer Storb, Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood 2001; 97(11): 3390–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederwieser D, Maris M, Shizuru JA, et al. Low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) and fludarabine followed by hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors and postgrafting immunosuppression with cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can induce durable complete chimerism and sustained remissions in patients with hematological diseases. Blood 2003; 101(4): 1620–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storb R, Gyurkocza B, Storer BE, et al. Graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-tumor effects after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(12): 1530–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblit B, Maloney DG, Storer BE, et al. A randomized phase II trial of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus after non-myeloablative unrelated donor transplantation. Haematologica 2014; 99(10): 1624–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Efron B Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika 1971; 58(3): 403–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant 1995; 15(6): 825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan KM. Graft-versus-host disease. In: Thomas ED, Blume KG, Forman SJ, eds. Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Malden, MA: Blackwell Sciences, Inc.; 1999: 515–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Statistics in Medicine 1999; 18(6): 695–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin PJ, McDonald GB, Sanders JE, et al. Increasingly frequent diagnosis of acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2004; 10(5): 320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maris MB, Niederwieser D, Sandmaier BM, et al. HLA-matched unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning for patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood 2003; 102(6): 2021–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marty FM, Bryar J, Browne SK, et al. Sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis protects against cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a cohort analysis. Blood 2007; 110(2): 490–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antin JH, Kim HT, Cutler C, et al. Sirolimus, tacrolimus, and low-dose methotrexate for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in mismatched related donor or unrelated donor transplantation. Blood 2003; 102(5): 1601–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claxton DF, Ehmann C, Rybka W. Control of advanced and refractory acute myelogenous leukaemia with sirolimus-based non-myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation. British Journal of Haematology 2005; 130(2): 256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cutler C, Li S, Ho VT, et al. Extended follow-up of methotrexate-free immunosuppression using sirolimus and tacrolimus in related and unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Blood 2007; 109(7): 3108–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alyea EP, Li S, Kim HT, et al. Sirolimus, tacrolimus, and low-dose methotrexate as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in related and unrelated donor reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2008; 14(8): 920–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furlong T, Kiem HP, Appelbaum FR, et al. Sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine or tacrolimus plus methotrexate for prevention of graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2008; 14(5): 531–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura R, Palmer JM, O’Donnell MR, et al. Reduced intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for MDS using tacrolimus/sirolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis. Leukemia Research 2012; 36(9): 1152–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim TK, DeVeaux M, Stahl M, et al. Long-term follow-up of a single institution pilot study of sirolimus, tacrolimus, and short course methotrexate for graft versus host disease prophylaxis in mismatched unrelated donor allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol 2019; 98(1): 237–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez R, Nakamura R, Palmer JM, et al. A phase II pilot study of tacrolimus/sirolimus GVHD prophylaxis for sibling donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using 3 conditioning regimens.[Erratum appears in Blood. 2010 May 27;115(21):4318]. Blood 2010; 115(5): 1098–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perez-Simon JA, Martino R, Parody R, et al. The combination of sirolimus plus tacrolimus improves outcome after reduced-intensity conditioning, unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared with cyclosporine plus mycofenolate. Haematologica 2013; 98(4): 526–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho VT, Aldridge J, Kim HT, et al. Comparison of tacrolimus and sirolimus (Tac/Sir) versus tacrolimus, sirolimus, and mini-methotrexate (Tac/Sir/MTX) as acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2009; 15(7): 844–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Kadhimi Z, Gul Z, Abidi M, et al. Low incidence of severe cGvHD and late NRM in a phase II trial of thymoglobulin, tacrolimus and sirolimus for GvHD prevention. Bone Marrow Transplant 2017; 52(9): 1304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pidala J, Kim J, Jim H, et al. A randomized phase II study to evaluate tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus or methotrexate after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica 2012; 97(12): 1882–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pulsipher MA, Langholz B, Wall DA, et al. The addition of sirolimus to tacrolimus/methotrexate GVHD prophylaxis in children with ALL: a phase 3 Children’s Oncology Group/Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium trial. Blood 2014; 123(13): 2017–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutler C, Logan B, Nakamura R, et al. Tacrolimus/sirolimus vs tacrolimus/methotrexate as GVHD prophylaxis after matched, related donor allogeneic HCT. Blood 2014; 124(8): 1372–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armand P, Kim HT, Sainvil MM, et al. The addition of sirolimus to the graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis regimen in reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for lymphoma: a multicentre randomized trial. Br J Haematol 2016; 173(1): 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greco R, Lorentino F, Morelli M, et al. Posttransplantation cyclophosphamide and sirolimus for prevention of GVHD after HLA-matched PBSC transplantation. Blood 2016; 128(11): 1528–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasamon YL, Ambinder RF, Fuchs EJ, et al. Prospective study of nonmyeloablative, HLA-mismatched unrelated BMT with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Blood Adv 2017; 1(4): 288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahl C, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, et al. Relapse risk among patients with malignant diseases given allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Blood 2007; 110(7): 2744–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.