Abstract

Objective

To investigate gender discrimination in access to healthcare and its relationship with the patient’s age and distance from the healthcare facility.

Design and setting

An observational study based on outpatient data from a large referral public hospital in Delhi, India.

Participants

Confirmed clinical appointments.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Estimates from the logistic regression are used to compute sex ratios (male/female) of patient visits with respect to distance from the hospital and age. Missing female patients for each state—a measure of the extent of gender discrimination—is computed as the difference in the actual number of female patients who came from each state and the number of female patients that should have visited the hospital had male and female patients come in the same proportion as the sex ratio of the overall population from the 2011 census.

Results

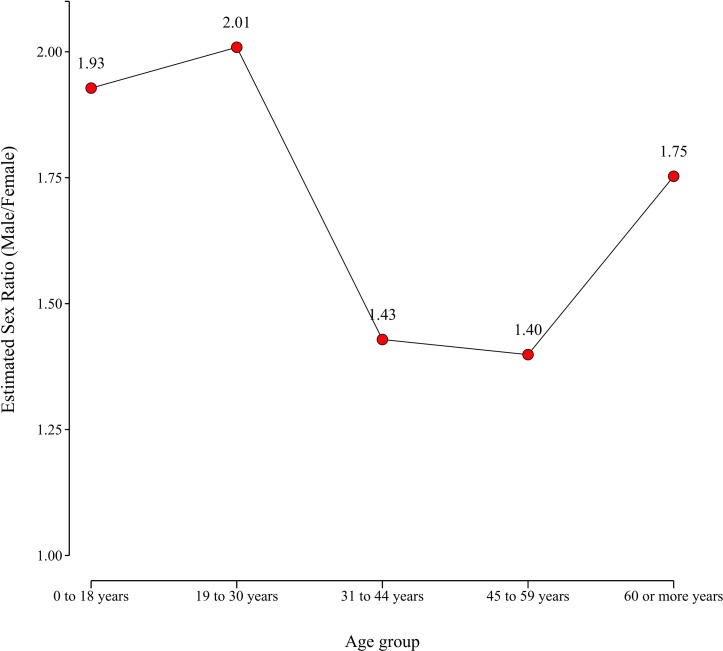

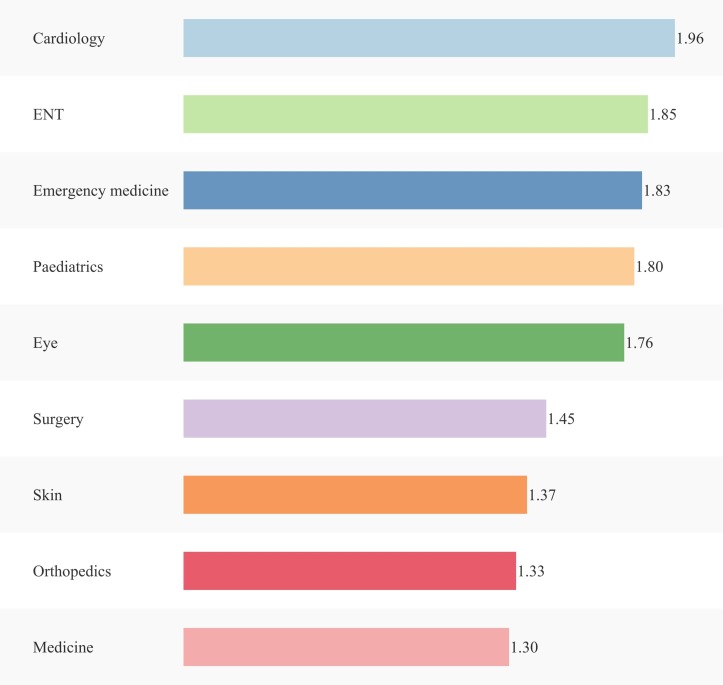

Of 2377028 outpatient visits, excluding obstetrics and gynaecology patients, the overall sex ratio was 1.69 male to one female visit. Sex ratios, adjusted for age and hospital department, increased with distance. The ratio was 1.41 for Delhi, where the facility is located; 1.70 for Haryana, an adjoining state; 1.98 for Uttar Pradesh, a state further away; and 2.37 for Bihar, the state furthest from Delhi. The sex ratios had a U-shaped relationship with age: 1.93 for 0–18 years, 2.01 for 19–30 years, and 1.75 for 60 years or over compared with 1.43 and 1.40 for the age groups 31–44 and 45–59 years, respectively. We estimate there were 402 722 missing female outpatient visits from these four states, which is 49% of the total female outpatient visits for these four states.

Conclusion

We found gender discrimination in access to healthcare, which was worse for female patients who were in the younger and older age groups, and for those who lived at increasing distances from the hospital.

Keywords: gender discrimination, access to public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used a large dataset of 2 377 028 clinical appointments from a referral, tertiary care public hospital with a robust hospital information system to study gender discrimination in access to healthcare.

Individual patient-level data were used to estimate the effect of age and distance of residence from the hospital on the gender distribution of outpatient visits to the hospital using logistic regression.

Based on the estimated sex ratio of visits to the outpatient department from different states and the respective sex ratio of those states according to the census, we compute the total number of missing female outpatient visits.

The study is limited in that it only considers data from a single hospital and may not capture all referrals from each state being studied.

Introduction

Gender discrimination in access to healthcare has not been systematically studied in India or many other developing countries. This is primarily due to a lack of reliable data. In this paper, we use extensive data collected on clinical appointments from a large public-funded tertiary care hospital with a robust hospital information system to study the level and extent of gender discrimination in access to healthcare. We used data on clinical appointments from 2 377 028 outpatients to analyse the likelihood of a male patient visit compared with a female patient visit to the hospital and its variation with respect to distance from the hospital and the age of the patient.

Previous studies on gender discrimination in developing countries have largely focused on the excess mortality of female patients as seen in low population ratios of women to men1–6 to explain the issue of missing women. This paper furthers these studies by assessing gender discrimination experienced by women in access to healthcare. There have been a handful of small sample studies on gender bias in access to healthcare in select patient groups or for specific medical conditions7–9; however, this study uses extensive data across a wide spectrum of patient groups and medical conditions to examine the gender discrimination in access to healthcare.

Methods

Data sources

In this study, we used data on outpatient visits to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi for the year 2016 across all outpatient departments except obstetrics and gynaecology. For each patient we analysed gender, age, state of residence, and the hospital outpatient department visited. We stratified patients into five age groups: 0–18 years, 19–30 years, 31–44 years, 45–59 years, and 60 years or over. More than 90% of the patients in the hospital travelled from one of the four states: Delhi, where the hospital is located; Haryana, an adjoining state to Delhi (capital of Haryana is 240 km away from Delhi); Uttar Pradesh, a state further away (capital of Uttar Pradesh is 555 km from Delhi); and Bihar, the furthest state from Delhi (capital of Bihar is 1110 km from Delhi).

Patient and public involvement

Anonymised patient data were used in this study. Patients and the public were not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Statistical analysis

Our statistical analysis is based on a logistic regression, where the dependent variable is the likelihood of a male patient visit. Our main explanatory variables are age group—which is an indicator variable for five different age groups (0–18 years, 19–30 years, 31-44 years, 45–59 years, and 60 years or over)—and state, which is an indicator variable for five states of residence of the patients (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, and other states). We also allowed the odds outcome to differ by age group for each state; therefore, we introduced an interaction term (age group×state). Unobserved differences across the departments in the likelihood of a male patient visit are accounted for by including an indicator variable for each department. We controlled for correlations across observations using clustered standard errors at the individual level given that some individuals visit the hospital multiple times. We used residents of Delhi in the age group 31–44 years as the reference group for the analysis.

Data were analysed with STATA 14.2/MP. We used the STATA command logit for logistic regression and vce(cluster id) for clusters at the level of the individual because some individuals visit the hospital multiple times in a given year. We reported odds ratios and computed 95% confidence intervals. STATA command lincom with option or was used to produce the odds ratios and the 95% confidence intervals for various combinations of the state of residence and the age group and their interaction effects, where residents of Delhi in the age group 31–44 years was the reference group. We used the margins command after the logistic regression to compute the marginal standardisation10 or the average predicted probabilities for male patient visits for age group, state and department, respectively. For example, for age group a, it is the proportion of male patient visits that we would have observed had we been able to force all observations in the sample to come from age group a, while all the other confounders are at the observed value. We performed a similar marginal standardisation analysis for state of residence and departments visited.

We define sex ratio as:

where s is the state: Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, and Delhi; and a is the age group: 0– 18 years, 19–30 years, 31–44 years, 45–59 years, 60 years or over.

For a given state s and age group a we define missing female patient visits as:

The estimated sex ratio for a given age group a is computed in two steps. First, after the logistic regression, we get the average predicted probability (APPa) of a male patient visit using the margins command in STATA, which is computed by forcing all the study population to the age group a, while all the other confounders are at the observed value. Second, we use this APPa to compute:

We performed a similar analysis to compute the estimated sex ratio for state s and estimated sex ratio for department.

Results

A total of 882 324 individuals visited the outpatient departments of the hospital an average 2.69 times in 2016, resulting in a total of 2 377 028 outpatients visits. Of these visits, 1 494 444 (63%) were by male patients and 882 584 (37%) were by female patients. Thus, the male/female outpatient visit ratio was 1.69, which is significantly greater than the overall sex ratio of 1.09 of the population, based on the last census (Census 2011). The sex ratio had a U-shaped relation with age. The ratio was higher for the younger age groups, 1.94 and 2.02 for age groups 0–18 years and 19–30 years, respectively; declined for the middle age groups to 1.45 and 1.38 for age groups 31–44 years and 45–59 years, respectively; and increased for the older age group to 1.72 for the age group 60 years and over. In addition, the ratio was proportional to the distance of residence of patients. The sex ratio of patients from Bihar, which is the furthest state from Delhi, was 2.37; it declined to 2.10 for patients coming from Uttar Pradesh, which is closer to Delhi compared with Bihar; it declined further to 1.68 for Haryana, which is the adjoining state to Delhi; and was the lowest for Delhi at 1.37. For each state, the sex ratio of the patient visiting the hospital was significantly greater than the overall sex ratio based on the 2011 population census: Delhi −1.15, Haryana −1.14, Uttar Pradesh −1.10, and Bihar −1.09 (see table 1).

Table 1.

Total male and female outpatient visits and sex ratio by age group and state of residence

| Total number of male and female outpatient visits and sex ratio by age group | ||||

| Age group | Male patient visits (A) |

Female patient visits (B) |

Sex ratio (C) = (A)/(B) |

|

| Young | 0–18 years | 385 624 | 199 108 | 1.94 |

| 19–30 years | 338 582 | 167 623 | 2.02 | |

| Middle | 31–44 years | 294 867 | 203 205 | 1.45 |

| 45–59 years | 258 687 | 186 871 | 1.38 | |

| Older | 60 years or over | 216 681 | 125 775 | 1.72 |

| Overall | Overall | 1 494 441 | 882 582 | 1.69 |

| Total number of male and female outpatient visits and sex ratio by state of residence | ||||

| States | Male patient visits (A) |

Female patient visits (B) |

Sex ratio (C) = (A)/(B) |

Sex ratio Census (2011) |

| Bihar | 200 716 | 84 926 | 2.37 | 1.09 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 359 914 | 171 033 | 2.10 | 1.10 |

| Haryana | 136 029 | 81 199 | 1.68 | 1.14 |

| Delhi | 663 406 | 484 160 | 1.37 | 1.15 |

| Other states | 134 379 | 61 266 | 2.19 | 1.09 |

| Overall | 1 494 444 | 882 584 | 1.69 | 1.09 |

| Sex ratio of outpatient visits and population in Census (2011) by age group and state of residence | |||||||||

| Age group | Bihar | Uttar Pradesh | Haryana | Delhi | |||||

| Outpatient visits | Census (2011) | Outpatient visits | Census (2011) | Outpatient visits | Census (2011) | Outpatient visits | Census (2011) | ||

| Young | 0–18 years | 2.76 | 1.11 | 2.26 | 1.12 | 2.00 | 1.22 | 1.62 | 1.18 |

| 19–30 years | 3.31 | 1.06 | 2.6 | 1.12 | 1.89 | 1.14 | 1.55 | 1.15 | |

| Middle | 31–44 years | 2.03 | 1.04 | 1.91 | 1.01 | 1.31 | 1.08 | 1.14 | 1.14 |

| 45–59 years | 1.56 | 1.06 | 1.67 | 1.07 | 1.44 | 1.09 | 1.18 | 1.18 | |

| Older | 60 years or over | 2.40 | 1.14 | 2.19 | 1.09 | 1.78 | 0.99 | 1.39 | 1.01 |

We also found that the U-shaped relationship between sex ratio and age group was present for all states.

The results of the sex ratio after adjusting for hospital department is shown in table 2. The ratios remain the same for age and distance. The U-shaped relation for age and sex ratio is present for each state, and for each age category the sex ratio is proportional to the distance of the state from the hospital, with the ratio being highest for the furthest state of Bihar (see table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CIs) of male patient visits based on logistic regression

| State | Age group | OR (95% CI) |

| Bihar | ||

| 0–18 years | 2.33 (2.20 to 2.47) | |

| 19–30 years | 3.00 (2.85 to 3.16) | |

| 31–44 years | 1.83 (1.74 to 1.91) | |

| 45–59 years | 1.41 (1.34 to 1.48) | |

| 60 years or over | 2.13 (2.01 to 2.25) | |

| Uttar Pradesh | ||

| 0–18 years | 1.93 (1.85 to 2.02) | |

| 19–30 years | 2.17 (2.09 to 2.25) | |

| 31–44 years | 1.44 (1.38 to 1.49) | |

| 45–59 years | 1.37 (1.32 to 1.42) | |

| 60 years or over | 1.88 (1.80 to 1.96) | |

| Haryana | ||

| 0–18 years | 1.72 (1.63 to 1.82) | |

| 19–30 years | 1.69 (1.61 to 1.78) | |

| 31–44 years | 1.17 (1.11 to 1.23) | |

| 45–59 years | 1.28 (1.22 to 1.35) | |

| 60 years or over | 1.56 (1.47 to 1.65) | |

| Delhi | ||

| 0–18 years | 1.44 (1.40 to 1.49) | |

| 19–30 years | 1.36 (1.33 to 1.40) | |

| 31–44 years* | 1.00 | |

| 45–59 years | 1.06 (1.03 to 1.09) | |

| 60 years or over | 1.22 (1.19 to 1.26) | |

| Other states | ||

| 0–18 years | 1.83 (1.72 to 1.94) | |

| 19–30 years | 2.51 (2.39 to 2.65) | |

| 31–44 years | 1.83 (1.73 to 1.93) | |

| 45–59 years | 1.48 (1.40 to 1.56) | |

| 60 years or over | 2.12 (1.99 to 2.26) |

*Delhi for the age group 31–44 years is the reference group. Adjustments have been made for the department visited. The standard errors are clustered at the individual patient level. The sex ratio of outpatient visits for the reference group is 1.14.

Next, we used the logistic regression results to estimate the sex ratio for different age groups while adjusting for the patient’s state of residence and the hospital departments they visit. In order to do this, we used the logistic regression coefficients to compute the average predicted probabilities for each age group. For example, based on the logistic regression, for the age group 0–18 years, 0.6585 (95% CI 0.6571 to 0.6600) was the average probability of a male patient visit if everyone in the data group were treated as if they were in the age group 0–18 years, while the other confounders are at the observed value. We then used these average predicted probabilities to estimate the sex ratio for the age group 0–18 years:

Similarly, we estimated the sex ratio for the other age groups. Our key finding is that the estimated sex ratio follows a U-shaped curve: it is significantly higher for the younger and older age groups compared with the middle age groups. For example, the ratio is high for age groups 0–18 years and 19–30 years at 1.93 and 2.01, respectively, then it declines to 1.43 and 1.40 for age groups 31–44 years and 45–59 years, respectively, and rises again for the older age group of 60 years and over to 1.75 (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted sex ratio of outpatient visits with respect to age group.

Similarly, we estimated the sex ratio of patients visiting from the states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Delhi after adjusting for the age group and the hospital departments visited by the patients, by using the results from the logistic regression. For example, in the case of Bihar, we found that 0.7026 (95% CI 0.6981 to 0.7070) is the average predicted probability of a male patient visit if everyone in the data group were treated as if they came from Bihar and all the other confounders were at the observed value. Based on this, we estimated the sex ratio from Bihar to be:

| . |

Similarly, we estimated the sex ratio for the other states and found that it declines to 1.98 for patients visiting from Uttar Pradesh, further declines to 1.70 for Haryana, and is the lowest for Delhi at 1.41 (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted sex ratio of outpatient visits with respect to state of residence.

The number of missing female patient visits based on sex ratios available for each state from the population Census (2011) is presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Missing female outpatient visits

| State | Age group | Male patient visits | Female patient visits (A) | Potential female patient visits* (B) | Missing female patient visits (C)=(B)–(A) |

Missing female patient visits (%) (C)/(A) |

| Bihar | ||||||

| 0–18 years | 54 327 | 19 702 | 48 943 | 29 241 | 148 | |

| 19–30 years | 48 293 | 14 588 | 45 559 | 30 971 | 212 | |

| 31–44 years | 39 341 | 19 416 | 37 828 | 18 412 | 95 | |

| 45–59 years | 30 182 | 19 321 | 28 474 | 9153 | 47 | |

| 60 years or over | 28 571 | 11 896 | 25 062 | 13 166 | 111 | |

| Uttar Pradesh | ||||||

| 0–18 years | 87 623 | 38 722 | 78 235 | 39 513 | 102 | |

| 19–30 years | 84 693 | 32 564 | 75 619 | 43 055 | 132 | |

| 31–44 years | 75 796 | 39 583 | 75 046 | 35 463 | 90 | |

| 45–59 years | 63 832 | 38 263 | 59 656 | 21 393 | 56 | |

| 60 years or over | 47 966 | 21 897 | 44 006 | 22 109 | 101 | |

| Haryana | ||||||

| 0–18 years | 39 930 | 20 004 | 32 730 | 12 726 | 64 | |

| 19–30 years | 27 170 | 14 357 | 23 833 | 9476 | 66 | |

| 31–44 years | 24 849 | 18 937 | 23 008 | 4071 | 21 | |

| 45–59 years | 23 211 | 16 168 | 21 294 | 5126 | 32 | |

| 60 years or over | 20 866 | 11 728 | 21 077 | 9349 | 80 | |

| Delhi | ||||||

| 0–18 years | 170 175 | 105 217 | 144 216 | 38 999 | 37 | |

| 19–30 years | 146 997 | 95 006 | 127 823 | 32 817 | 35 | |

| 31–44 years | 129 007 | 112 939 | 113 164 | 225 | 0.20 | |

| 45–59 years | 116 311 | 98 222 | 98 569 | 347 | 0.35 | |

| 60 years or over | 100 909 | 72 750 | 99 910 | 27 160 | 37 | |

| Overall | 821 280 | 402 772 | 49 | |||

*Potential female patient visits are defined as the number of female patient visits if they were in the same proportion as the state census sex ratio of the population (2011).

The results, for example, show that from Bihar there was a total of 14 588 female and 48 293 male patient visits to the hospital in the age group 19–30 years. If the female patients from Bihar had visited in the same proportion as the male to female ratio of the census, then the total number of female patients visits from Bihar would have been 45 559. Therefore, the number of missing female patient visits from Bihar for the age group 19–30 years is 30 971, which is approximately 212% of the total female visits from Bihar for that particular age group.

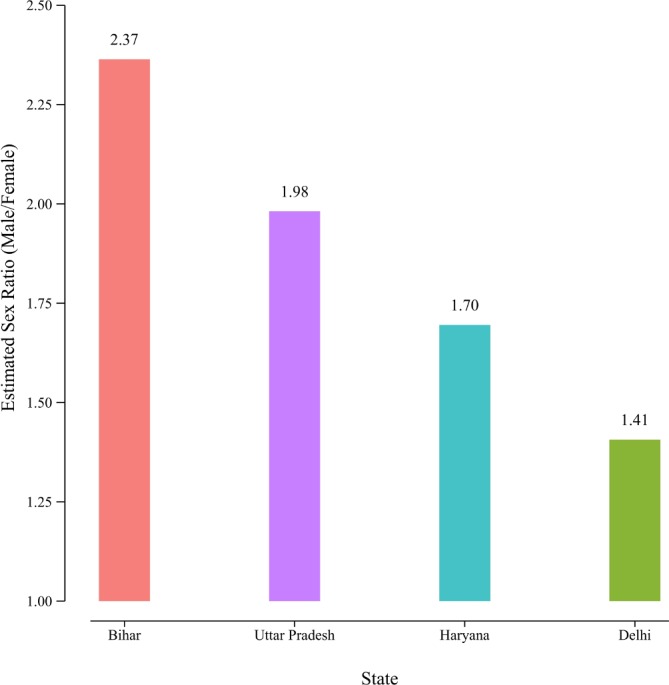

We also estimated the sex ratio of patient visits to the 10 most visited departments and found that there was wide variation: the highest estimated sex ratio was 1.96 for the Cardiology Department, while it was the lowest at 1.30 for the Department of Medicine (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sex ratio of outpatient visits with respect to various departments.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study from India that uses extensive data on 2 377 028 clinical appointments from a large public-funded tertiary care hospital with a robust hospital information system to demonstrate gender discrimination in access to healthcare. We have shown that the extent of discrimination varies with respect to distance from the facility and age. Female patients who reside further away from the facility are less likely to visit the facility. Additionally, the extent of discrimination varies with respect to age; females in the younger and older age groups are less likely to visit the hospital compared with middle-aged women. Previous studies on gender discrimination have largely restricted the discussion to the excess mortality of females with respect to men. By contrast, our study computes the missing female patient visits with respect to distance to the hospital and age, which highlights real-time discrimination against women in access to a healthcare facility. This discrimination of women is not fully captured in the overall sex ratio or excess mortality of women relative to men. The variation in access to tertiary healthcare dependent on distance from the facility is not captured in overall sex ratios, which are similar for these four states.

Our study has important implications for gender-related health policy which has so far largely focused on maternal health. The findings suggest local healthcare infrastructure should be strengthened, with the biggest beneficiaries being younger and older women who are most neglected and discriminated against.

In the Indian context, there have been some small studies of select groups of patients or for specific medical conditions that have looked at gender bias in access to healthcare. For example, a study from the same health facility reported gender bias in children with congenital heart disease: the likelihood of a male child undergoing corrective cardiac surgery is 3.5 times higher compared with a female child.11 Other studies have found gender discrimination in the uptake of free medical care in government-funded school screening programmes, where fewer female children accessed the hospital compared with male children for cardiac ailments (with a male to female ratio of 1.7).8 There have been some studies that have reported gender bias beyond healthcare access and management, in areas of immunisation, food allocation and percentage of household expenditures.7 Some studies have also looked at the gender gap in parents’ financing strategies for hospitalisation of their children and observe that a male child is much more likely to be hospitalised for serious ailments than a female child.12 The bias increases in poorer households and with more onerous sources of medical financing.12

Gender bias has also been reported among adults in the treatment of specific diseases. Studies from the developing and developed world suggest that women are less likely to receive thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction,13 undergo angiography14 and cardiac surgery.15 The European registry data16 suggest that female patients have worse risk factor profiles and are less likely to meet the target goals for lipids, diabetes, physical activity and weight loss. Gender bias is also observed in prehospital care where research has shown that male patients have a 2.75 higher odds (95% CI 1.2 to 6.2) of receiving highest priority care compared with female patients after controlling for injury mechanism and vital signs on scene based on trauma registries and ambulance records in Sweden.17

The strength of this paper is the large number of outpatient visits available for analysis. This paper, however, has several limitations. The results are based on data from a single hospital in Delhi. However, as mentioned, this is a large hospital with more than 2 million annual outpatient visits and a large referral base from the states studied. The addresses are not based on a national database but are self-declared and there is a tendency for an over representation of local addresses. However, in that case, the sex ratio of Delhi would only decrease, and thus the gender bias would be higher in other states than are reported here. A criticism of the study could be that the sex ratio could be reflective of disease infliction and not gender bias. However, this is unlikely since it involves multiple departments of this multi-specialty hospital encompassing several branches of medicine and any gender predilection would get balanced across specialties. Moreover, in our logistic regression we have adjusted for department-specific effects by including a department-level fixed effect. Another potential limitation is that women in distant areas would prefer using healthcare facilities closer to home and for this reason the sex ratio is more skewed in distant states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Additionally absence of data on referral from these states to any other hospital and the sex ratio in them are not available and could impact. For example, if there are other referral hospitals visited by residents from these states, which have more female outpatient visits than male outpatient visits, then this would have a significant impact on our current interpretation. However, it is important to note that there is a significant difference in the quality of care that is provided in premium public institutions such as AIIMS and the local public health facilities in states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Furthermore, the Government of India has noted that there is a significant shortage of doctors and health providers in public health facilities in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar; in the case of Bihar it is greater than 50%. These states are ranked among the bottom three states in terms of health index of the states. A key implication of this is that, relative to men, women in these states are deprived of quality tertiary care.

In conclusion, this study, which is based on a large number of outpatient visits, suggests there is extensive gender discrimination in healthcare access, with the situation worsening for younger and older female patients and those residing at increasing distances from the referral hospital. This calls for systemic societal and governmental action to correct this gender discrimination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper benefited from discussion with A K Shiva Kumar and seminar participants at Brookings Institution, India and Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi, India. We also gratefully acknowledge HCL Foundation grant to Brookings India which covered the publication charges.

Footnotes

MK and DA contributed equally.

Contributors: DA: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. MK: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. SR: Substantial contributions to the conception of the work; interpretation of data for the work. AR: Substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work. SVS: Substantial contributions to the design of the work; the interpretation of data for the work. RG: Substantial contributions to the design of the work; the interpretation of data for the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for this study was received from All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) ethical review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The hospital information system was queried for all confirmed clinical appointments in the year 2016. The data were made available from the Hospital Administration System for this study and are not publicly available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. The New York Review of Books. More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing | by Amartya Sen |. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1990/12/20/more-than-100-million-women-are-missing/ (accessed 18 Mar 2019).

- 2. Sen A. Missing women--revisited. BMJ 2003;327:1297–8. 10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bongaarts J, Guilmoto C. How many more missing women? Lancet 2015;386:427 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61439-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson S, Ray D. Missing women: age and disease. Review of Economic Studies 2010;77:1262–300. 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2010.00609.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson S, Ray D. The Age Distribution of Missing Women in India. EPW 2012:87. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balan S, Mahalingam R. Are we losing the war on missing girls? Lancet Glob Health 2014;2:e22 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70183-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Khera R, Jain S, Lodha R, et al. Gender bias in child care and child health: global patterns. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:369–74. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chhabra ST, Masson S, Kaur T, et al. Gender bias in cardiovascular healthcare of a tertiary care centre of North India. Heart Asia 2016;8:42–5. 10.1136/heartasia-2015-010710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mathew JL. Inequity in childhood immunization in India: a systematic review. Indian Pediatr 2012;49:203–23. 10.1007/s13312-012-0063-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:962–70. 10.1093/ije/dyu029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramakrishnan S, Khera R, Jain S, et al. Gender differences in the utilisation of surgery for congenital heart disease in India. Heart 2011;97:1920–5. 10.1136/hrt.2011.224410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Asfaw A, Lamanna F, Klasen S. Gender gap in parents' financing strategy for hospitalization of their children: evidence from India. Health Econ 2010;19:265–79. 10.1002/hec.1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bugiardini R, Estrada JL, Nikus K, et al. Gender bias in acute coronary syndromes. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2010;8:276–84. 10.2174/157016110790887018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nguyen JT, Berger AK, Duval S, et al. Gender disparity in cardiac procedures and medication use for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2008;155:862–8. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.11.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Worrall-Carter L, McEvedy S, Wilson A, et al. Gender Differences in Presentation, Coronary Intervention, and Outcomes of 28,985 Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in Victoria, Australia. Womens Health Issues 2016;26:14–20. 10.1016/j.whi.2015.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Smedt D, De Bacquer D, De Sutter J, et al. The gender gap in risk factor control: Effects of age and education on the control of cardiovascular risk factors in male and female coronary patients. The EUROASPIRE IV study by the European Society of Cardiology. Int J Cardiol 2016;209:284–90. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rubenson Wahlin R, Ponzer S, Lövbrand H, et al. Do male and female trauma patients receive the same prehospital care?: an observational follow-up study. BMC Emerg Med 2016;16 1 6:6. 10.1186/s12873-016-0070-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.