Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) versus conventional oxygen therapy (COT) on the reintubation rate, rate of escalation of respiratory support and clinical outcomes in postextubation adult surgical patients.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of published literature.

Data sources

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Index and Wan fang databases were searched up to August 2018.

Eligibility criteria

Studies in postoperative adult surgical patients (≥18 years), receiving HFNC or COT applied immediately after extubation that reported reintubation, escalation of respiratory support, postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) and mortality were eligible for inclusion.

Data extraction and synthesis

The following data were extracted from the included studies: first author’s name, year of publication, study population, country of origin, study design, number of patients, patients’ baseline characteristics and outcomes. Associations were evaluated using risk ratio (RR) and 95% CIs.

Results

This meta-analysis included 10 studies (1327 patients). HFNC significantly reduced the reintubation rate (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.61, p<0.0001) and rate of escalation of respiratory support (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.73, p=0.002) in postextubation surgical patients compared with COT. There were no differences in the incidence of PPCs (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.08, p=0.21) or mortality (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.29, p=0.14).

Conclusion

HFNC is associated with a significantly lower reintubation rate and rate of escalation of respiratory support compared with COT in postextubation adult surgical patients, but there is no difference in the incidence of PPCs or mortality. More well-designed, large randomised controlled trials are needed to determine the subpopulation of patients who are most likely to benefit from HFNC therapy.

Keywords: high flow nasal cannula, surgical patients, re-intubation, escalation of respiratory support, mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This meta-analysis synthesised data from randomised trials and observational studies to analyse the effect of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) versus conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation rate, rate of escalation of respiratory support and incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality in postextubation surgical patients.

The possible risk of bias for randomised controlled trials and case-control and cohort studies was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration methodology or the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Sources of heterogeneity between studies were investigated using random-effects meta-regression. Subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the subpopulation of patients who were most likely to benefit from HFNC therapy.

However, the clinical heterogeneity between trials included was relatively high, and a patient level meta-analysis might still be needed.

Introduction

Postoperative respiratory failure is associated with perioperative morbidity and mortality in surgical patients and high costs of healthcare.1 2 Causes of early postoperative respiratory failure include hypoxaemia, diaphragmatic dysfunction, atelectasis due to postoperative alveolar collapse or fluid accumulation.3 4 Prophylactic strategies such as protective intraoperative mechanical ventilation, postoperative physiotherapy and non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) may reduce the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) and improve the prognosis of surgical patients.5 In particular, some evidence supports the use of NIV for postoperative respiratory failure6; however, this technique requires substantial resources and technical expertise and may cause discomfort to patients.7

High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) is increasingly used in the prevention and treatment of respiratory failure in postextubation non-surgical and surgical patients.6 8 9 The advantages of HFNC compared with conventional oxygen therapy (COT) include improved comfort, delivery of a predictable sustained PaO2 of oxygen due to a reduction of room air entrainment, good humidification, decreased anatomical dead space and positive end-expiratory pressure.3 4 10–14 However, failure of HFNC in patients with pulmonary complications can lead to delayed intubation causing morbidity and mortality.15 Therefore, the safety and efficacy of HFNC are being increasingly investigated in the literature, but findings are inconsistent.16–18 In an attempt to provide some clarity, the present systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effect of HFNC versus COT on the reintubation rate, rate of escalation of respiratory support and clinical outcomes in postextubation adult surgical patients.

Methods

Data sources and searches

The PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Index and Wan fang databases were searched from inception to 31 August 2018 using the following keywords: (‘high flow’ or ‘high-flow’) and (‘operation’ or ‘operative’ or ‘surgery’ or ‘Surgical’) (see online supplementary figure 1). Additional studies were identified by manually searching the reference lists from relevant articles and reviews. No restrictions on language or study design were applied.

bmjopen-2018-027523supp001.jpg (40KB, jpg)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study population: postoperative adult surgical patients (≥18 years); (2) interventions: HFNC versus COT; HFNC or COT were applied immediately after extubation; COT was administered via a cool mist/nasal cannula (CM/NC) or face mask and (3) outcomes: reintubation, escalation of respiratory support, PPCs and mortality.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies in postoperative surgical patients who did not receive HFNC after extubation; (2) use of a control other than COT; (3) reviews, letters, case reports or (4) in vitro studies or animal experiments.

Study selection

Two review authors (ZL, S-SM) independently assessed titles and abstracts to determine if a study met the inclusion criteria. The full text of potentially relevant studies was retrieved and reviewed. Disagreements about study selection were resolved thorough discussion with a third reviewer (WC) until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Two review authors (ZL, S-SM) independently extracted data from the included studies, including first author’s name, year of publication, study population, country of origin, study design, number of patients, patients’ baseline characteristics and outcomes.

Primary outcomes were reintubation rate and rate of escalation of respiratory support. In postextubation adult surgical patients receiving COT, respiratory support was escalated to HFNC, NIV or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) according to the following algorithms: COT→HFNC, COT→NIV, COT→HFNC→IMV, COT→NIV→IMV. In postextubation adult surgical patients receiving HFNC, respiratory support was escalated to NIV or IMV according to the following algorithms: HFNC→NIV, HFNC→IMV, HFNC→NIV→IMV. Respiratory therapy was escalated when the patient progressed to acute respiratory failure or due to other causes.

Secondary outcomes were the incidence of PPCs, defined as PPCs identified in the original article, new postoperative pneumonia and atelectasis, and in-hospital or 28-day mortality. Disagreements about data extraction were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (WC) until consensus was reached.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias in included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration methodology,19 which evaluates the following domains: adequacy of sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding of participants and caregivers, blinding for outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and the other sources of bias. Risk of bias was evaluated as ‘low risk’, ‘high risk’ or ‘unclear risk’. Risk of bias in included case-control or cohort studies was assessed using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale, which includes three categories: selection, comparability and exposure or outcome, with each study awarded a maximum of nine stars.20

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with Review Manager Software V.5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) and STATA V.12.0 (StataCorp). Categorical variables are presented as proportions or ratios, and associations were evaluated using risk ratio (RRs) and 95% CIs. Random-effects model attempted to generalise findings beyond the included studies by assuming that the selected studies are random samples from a larger population,21 so it was used to pool studies to account for the substantial clinical heterogeneity (patients’ age, type of surgery, types of controls (CM/NC or face mask), length of follow-up) between studies.

Heterogeneity between studies was quantified by the χ2and I2 tests. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed as low (I2=25%), medium (I2=50%) or high (I2=75%).22 Univariable random-effects meta-regression was performed to investigate sources of heterogeneity between studies.

Subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the subpopulation of patients who were most likely to benefit from HFNC therapy. Subgroups were stratified by type of surgery (cardiac, thoracic or mixed surgery), study design (non-RCT or RCT), target SPO2 level (90%–93% or 95%), strategy (prophylactic or therapy) and risk of reintubation (high risk or low risk: the average values of risk-related parameters for reintubation were assessed as previously reported9 10).

Sensitivity analysis, excluding one study at a time, was performed to explore the impact of study quality on the overall effect estimate of all included studies. Publication bias was evaluated by Begg’s funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence limits.

The level of evidence of included studies was qualified using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework.

A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and the public were not involved in this review.

Results

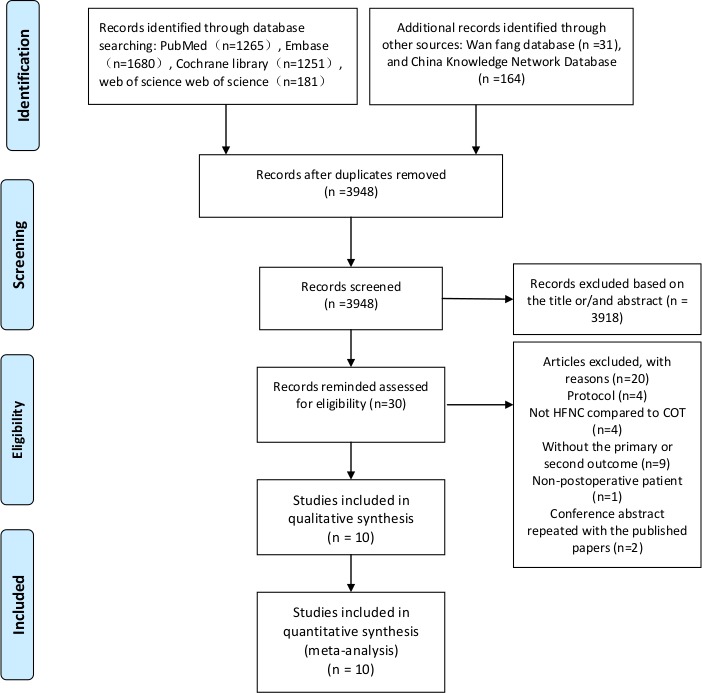

The searches identified 4572 potentially relevant articles, and 624 duplicates were excluded. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 30 studies were considered potentially eligible for inclusion. After analysing the full text articles or conference abstracts, 10 studies were included in the final analyses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in table 1. The studies were published between 2013 and 2018 and were conducted in Oceania, Europe, Asia and American. Seven studies were RCTs, two were case-control studies and one was a cohort study. The 10 studies included a total of 1327 postextubation adult surgical patients, of which 615 patients received HFNC and 712 received COT. Three studies were in patients who had undergone cardiac surgery,17 23 24 five studies were in patients who had undergone thoracic surgery25–29 and two studies were mixed, including patients16 18 who had undergone various types of surgeries. The patients were followed-up until intensive care unit (ICU) or hospital discharge.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Study design | Type of surgery | Patient characteristics (HFNC/COT) | Target SPO2 (%) | Risk of reintubation | ||

| Patient number | BMI | Age (years) | |||||

| Chen et al 27 | Case–control study | Thoracic | 44/45 | NA | 66/64 | 90 | High |

| Xu et al 24 | Cohort study | Cardiovascular | 45/45 | 26/27 | 57/54 | 95 | High |

| Brainard et al 26 | RCT | Thoracic | 18/26 | 26/25 | 57/59 | 95 | NA |

| Dhillon et al 16 | Case–control study | Mixed | 46/138 | NA | 63/58 | NA | NA |

| Geng28 | RCT | Thoracic | 25/23 | NA | 63/63 | 90 | High |

| Sun and Zhu29 | RCT | Thoracic | 24/24 | NA | 67/65 | 100 | High |

| Yu et al 25 | RCT | Thoracic | 56/54 | 26/25 | 56/56 | 95 | High |

| Futier et al 18 | RCT | Abdominal or combine thoracic | 108/112 | 25/25 | 62/661 | 95 | NA |

| Corley et al 11 | RCT | Cardiovascular | 81/74 | 36/35 | 63/65 | 95 | High |

| Parke et al 17 | RCT | Cardiovascular | 169/171 | 28/29 | 65/66 | 93 | High |

| Study | Characteristics of oxygen therapy (HFNC/COT) | Escalation of respiratory support* | Strategy | Study centre | Follow-up time: primary outcomes | ||

| HFNC flow rate (L/min) | COT | HFNC | COT | ||||

| NIV/intubation | HFNC/NIV/intubation | ||||||

| Chen et al 27 | 35–60 | Facemask | NA/7 | NA/19 | Therapy | Single centre | 2 days |

| Xu et al 24 | 35–60 | 5–10 L/min face mask | 0/1 | 0/0/7 | Prophylactic | Single centre | 3 days |

| Brainard et al 26 | 40 | Nasal cannula or face mask | NA/1 | NA/NA/2 | Prophylactic | Single centre | 2 days |

| Dhillon et al 16 | NA | Cool mist/nasal cannula (CM/NC) | NA/NA/3 | NA/NA/19 | Prophylactic | Single centre | NA |

| Geng28 | 35–60 | Facemask | NA/NA/1 | NA/NA/9 | Therapy | Single centre | NA |

| Sun and Zhu29 | 40–60 | 8–10 L/min atomising mask | 1/3 | 0/3/8 | Therapy | Single centre | 1 day |

| Yu et al 25 | 35–60 | Nasal prongs or facemask | 2/0 | 9/5/0 | Prophylactic | Multicentre | 3 days |

| Futier et al 18 | 50–60 | Nasal prongs or facemask | NA/NA (20)† | NA/NA/NA (14)† | Prophylactic | Multicentre | 7 days |

| Corley et al 23 | 35–50 | 2–4 L/min via nasal cannulae or 6 L/min via simple face mask | 3/0 | 1/2/2 | Prophylactic | Single centre | 1 day |

| Parke et al 17 | 45 | 2–4 L/min via simple facemask or nasal prongs | 9/2 | 18/5/0 | Prophylactic | Single centre | 2 days |

Data are expressed as median (IQR) or mean (SD).

*Only the final oxygen treatment was recorded.

†Only got the total number.

COT, conventional oxygen therapy; HFNC, high- flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy; NA, not available or not reported; NIV, non-invasive mechanical ventilation; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

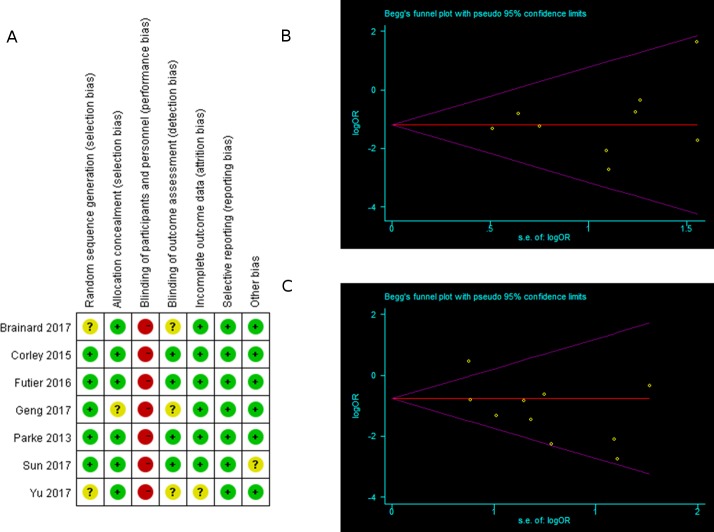

Assessment of risk of bias

The results of the quality assessments are shown in figure 2A and table 2. None of the included studies were double blind. In the RCTs, blinding of patients and caregivers was impossible, and most authors regarded this as a limitation associated with their studies. One trial had reporting bias. Four trials were classified as having an unclear risk of bias.25 26 28 29

Figure 2.

(A) Risk of bias summary for each included study. Red (–) indicates high risk of bias; yellow (?) indicates unclear risk and green (+) indicates low risk of bias. (B, C) Funnel plot for publication bias: (B) reintubation rate; (C) rate of escalation of respiratory support.

Table 2.

Quality assessment: Newcastle-Ottawa scale

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Overall stars | |||||

| Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | ||

| Xu et al 24 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | – | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Chen et al 27 | ★ | ★ | – | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 7 |

| Dhillon et al 16 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | – | ★ | ★ | 7 |

★, the quality met the criterion of this specific item; –, self-reported or unstated.

All the non-RCTs received seven stars on the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale because the assessment of outcomes was self-reported or unstated in the cohort study, and the selection of controls was not described in the case-control studies.

Begg’s funnel plot revealed no evidence of publication bias for the primary outcomes, except for one outlier in the analysis of escalation of respiratory support18 (figure 2B,C).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

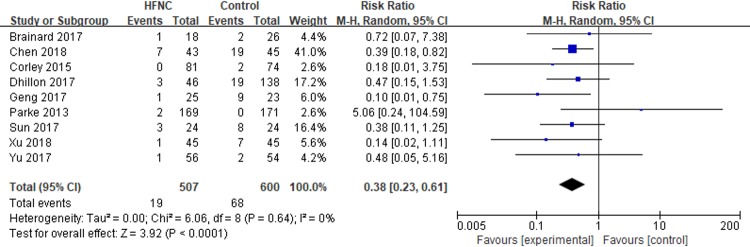

Nine studies reported on the reintubation rate in postextubation adult surgical patients who received HFNC (n=507) or COT (n=600). The meta-analysis demonstrated that the reintubation rate was significantly lower in patients who received HFNC compared with those who received COT (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.61, p<0.0001). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) versus conventional oxygen therapy: reintubation rate.

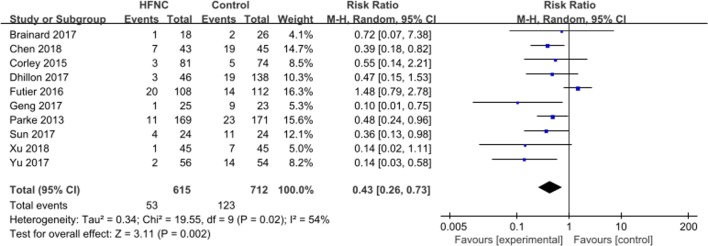

Ten studies reported on the rate of escalation of respiratory support in postextubation adult surgical patients who received HFNC (n=615) or COT (n=712). The meta-analysis demonstrated that the rate of escalation of respiratory support was significantly lower in patients who received HFNC compared with those who received COT (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.73, p=0.002). There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2=54%) (figure 4).

Figure 4.

High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy (HFNC) versus conventional oxygen therapy: rate of escalation of respiratory support.

Secondary outcomes

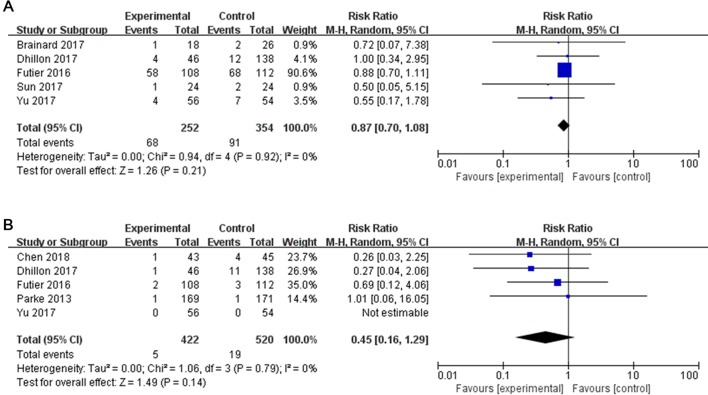

Five studies reported on the incidence of PPCs in postextubation adult surgical patients who received HFNC (n=252) or COT (n=354). The meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the incidence of PPCs in patients who received HFNC compared with those who received COT (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.08, p=0.21). There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%) (figure 5A).

Figure 5.

High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy versus conventional oxygen therapy: (A) postoperative pulmonary complications; (B) hospital mortality.

Five studies reported on mortality in postextubation adult surgical patients who received HFNC (n=422) or COT (n=520). Five patients (1.18%) who received HFNC and 19 patients who received COT died. However, the meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in mortality in patients who received HFNC compared with those who received COT (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.29, p=0.14) (figure 5B).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses stratified by type of surgery (cardiac, thoracic or mixed surgery), study design (non-RCT or RCT), target SPO2 level (90%–93% or 95%), strategy (prophylactic or therapy) and risk of reintubation (high risk or low risk) showed similar effect estimates for the primary and secondary outcomes as the overall analysis (table 3), except for cardiac surgery, prophylactic strategy and target SPO2 level (90%–93%), where there was no significant difference in the reintubation rate in postextubation adult surgical patients who received HFNC compared with those who received COT, and target SPO2 level (95%), where there was no significant difference in the rate of escalation of respiratory support in postextubation adult surgical patients who received HFNC compared with those who received COT.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses

| Outcome | No studies (no of patients) | Summary estimate (95% CI) | P value (summary estimate) | P value (heterogeneity) | I2 (%) |

| Reintubation | 9 (1107) | 0.38* (0.23 to 0.61) | 0.0001 | 0.64 | 0 |

| Cardiac surgery | 3 (585) | 0.43* (0.05 to 3.72) | 0.44 | 0.14 | 49 |

| Thoracic surgery | 5 (338) | 0.36* (0.20 to 0.64) | 0.0005 | 0.73 | 0 |

| RCT | 6 (745) | 0.39* (0.17 to 0.87) | 0.02 | 0.41 | 1 |

| Non-RCT | 3 (362) | 0.37* (0.20 to 0.69) | 0.002 | 0.60 | 0 |

| Min target SPO2(90%–93%) | 3 (476) | 0.41* (0.09 to 1.92) | 0.26 | 0.11 | 55 |

| Min target SPO2 (95%) | 4 (399) | 0.31* (0.09 to 1.01) | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0 |

| Prophylactic | 7 (1143) | 0.46* (0.21 to 1.03) | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0 |

| Therapy | 3 (184) | 0.34* (0.18 to 0.62) | 0.0005 | 0.45 | 0 |

| High risk of reintubation | 7 (879) | 0.35* (0.20 to 0.60) | 0.0002 | 0.48 | 0 |

| Escalation rate of respiratory support | 10 (1327) | 0.43* (0.26 to 0.73) | 0.002 | 0.02 | 54 |

| Cardiac surgery | 3 (585) | 0.45* (0.25 to 0.81) | 0.008 | 0.51 | 0 |

| Thoracic surgery | 5 (338) | 0.31* (0.18 to 0.53) | 0.0001 | 0.47 | 0 |

| RCT | 7 (965) | 0.46* (0.22 to 0.93) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 64 |

| Non-RCT | 3 (362) | 0.37* (0.20 to 0.69) | 0.002 | 0.60 | 0 |

| Min target SPO2(90%–93%) | 3 (476) | 0.39* (0.23 to 0.67) | 0.0005 | 0.34 | 8 |

| Min target SPO2 (95%) | 5 (619) | 0.46* (0.15 to 1.44) | 0.18 | 0.01 | 70 |

| Prophylactic | 7 (1143) | 0.50* (0.25 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.02 | 59 |

| Therapy | 3 (184) | 0.34* (0.19 to 0.60) | 0.0002 | 0.45 | 0 |

| High risk of reintubation | 7 (879) | 0.33* (0.22 to 0.49) | 0.00001 | 0.5 | 0 |

| PPCs | 5 (606) | 0.87* (0.70 to 1.08) | 0.21 | 0.92 | 0 |

| RCT | 4 (422) | 0.86* (0.69 to 1.086) | 0.20 | 0.83 | 0 |

| Prophylactic | 4 (558) | 0.86* (0.68 to 1.08) | 0.20 | 0.87 | 0 |

| Mortality | 5 (942) | 0.45* (0.16 to 1.29) | 0.14 | 0.79 | 0 |

| Cardiac surgery | 1 (340) | 1.01* (0.06 to 16.05) | 0.99 | – | – |

| Thoracic surgery | 2 (198) | 0.26* (0.03 to 2.25) | 0.22 | – | – |

| RCT | 3 (670) | 0.77* (0.17 to 3.41) | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0 |

| Non-RCT | 2 (272) | 0.27* (0.06 to 1.18) | 0.08 | 0.98 | 0 |

| Min target SPO2(90%–93%) | 2 (428) | 0.41* (0.08 to 2.09) | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0 |

| Min target SPO2 (95%) | 2 (330) | 0.69* (0.12 to 4.06) | 0.68 | – | – |

| High risk of reintubation | 3 (538) | 0.41* (0.08 to 2.09) | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0 |

*Relative risk.

PPCs, postoperative pulmonary complications; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Random-effects meta-regression

Meta-regression was used to analyse the sources of statistical heterogeneity between studies in the analyses investigating the rate of escalation of respiratory support. Type of surgery (b=0.262, p=0.027) and risk factors for intubation (b=2.358, p=0.006) were found to be a potential source of statistical heterogeneity (see online supplementary figure 2).

bmjopen-2018-027523supp002.jpg (64.9KB, jpg)

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses excluding one study at a time showed similar effect estimates for the primary and secondary outcomes as the overall analysis (see online supplementary figure 3).

bmjopen-2018-027523supp003.jpg (146.4KB, jpg)

GRADE

Evidence was qualified using GRADE. Overall, high-quality evidence showed that HFNC may have benefit when compared with COT in reducing the reintubation rate in postextubation adult surgical patients; however, the level of evidence for the case-control study was low (see online supplementary table 1A).

bmjopen-2018-027523supp004.pdf (410.9KB, pdf)

Overall, low quality of evidence showed that HFNC may have benefit when compared with COT in reducing the need to escalate respiratory support in postextubation adult surgical patients. The level of evidence was downgraded due to medium statistical heterogeneity between studies, uncertain publication bias and the low evidence quality of the case control study (see online supplementary table 1B).

Discussion

The results from the present systematic review and meta-analysis of data from 10 studies suggest that HFNC is associated with a significantly lower reintubation rate and rate of escalation of respiratory support compared with COT in postextubation adult surgical patients, but there is no difference in the incidence of PPCs or mortality. Subgroup analysis showed that HFNC reduced the reintubation rate and the rate of escalation of respiratory support compared with COT in both randomised controlled trials and observational studies. These data suggest that the beneficial effects of HFNC, including washout of anatomic dead space, improved gas mixing in large airways, heating and humidification of inhaled gas, increased end-expiratory lung volume, improved oxygenation and reduced respiratory rate and inspiratory effort,30–33 are consistent across healthcare settings and treatment strategies.

Previous studies have investigated the safety and efficacy of HFNC in surgical and non-surgical patients. Two systematic reviews used traditional pairwise comparisons to evaluate the effectiveness of HFNC and COT in postextubation adult patients.34 35 In a meta-analysis including 2 studies and 495 cardiac surgical patients, Zhu et al found that HFNC after extubation was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of escalation of respiratory support compared with COT, but did not decrease reintubation rate or the length of intensive care unit stay.35 In a meta-analysis including 7 studies and 2781 adult patients, HFNC after extubation had a similar reintubation rate compared with either COT or NIV. However, in a subgroup analysis of critically ill patients, HFNC after extubation had a lower reintubation rate compared with COT.34 In a study that assessed overall ICU mortality and other hospital outcomes in patients who received HFNC therapy that failed, failure of HFNC resulted in delayed intubation and worse clinical outcomes. Early intubated patients had better overall ICU mortality, extubation success, ventilator weaning and more ventilator-free days than late intubated patients.15 Taken together, the findings from the present review and these previous studies suggest that larger, well-designed RCTs are required to further investigate the safety and efficacy of HFNC in postextubation adult surgical patients.

In the present review, there was ‘medium’ heterogeneity between studies included in the analyses investigating the rate of escalation of respiratory support. This is not surprising, given the differences in type of surgery, study design, target SPO2, therapeutic strategy and risk of reintubation between the studies included in the analysis of this outcome. Meta-regression identified type of surgery and the risk factors for reintubation as the main sources of heterogeneity.

Our subgroup analyses showed no improvement in the reintubation rate in patients who had undergone cardiac surgery and received HFNC compared with COT postextubation. Cardiac patients are at high risk for PPCs, and thus many may not benefit from HFNC. Assess Respiratory Risk in Surgical Patients in Catalonia(ARISCAT) risk index, including age, low oxygen saturation at rest, preoperative low hemoglobin level, type of incision, length of surgery, history of lower respiratory tract infection 1 month before surgery, and need for emergency surgery, which predicts the risk of PPCs after surgery, suggests that patients undergoing cardiac surgery have a high risk for PPCs, likely due to the intrathoracic incision and longer duration of surgery, which may be extended by the need for extracorporeal circulation.15

The subgroup analysis stratified by risk for reintubation showed that HFNC was associated with a lower reintubation rate and rate of escalation of respiratory support compared with COT in postextubation patients with a high risk for reintubation. Consistent with this finding, previous reports show that HFNC reduced reintubation rate compared with COT in critically ill patients with low risk of intubation10 and was not inferior to NIV for preventing reintubation and postextubated respiratory failure in critically ill patients at high risk of intubation.9

The present study suggests that when SPO2 is maintained above 90%–93%, HFNC may have benefit compared with COT in reducing the need to escalate respiratory support, but not for decreasing the reintubation rate. Conversely, when SPO2 was maintained above 95%, HFNC reduced the reintubation rate but not the rate of escalation of respiratory support. The advantages of reducing the need to escalate respiratory support at the lower SPO2 threshold versus delaying the time to reintubation at the higher SPO2 threshold remain to be elucidated. Recent studies show that critically ill patients treated with conservative oxygen therapy (with a slightly lower SPO2 target) versus conventional therapy had a lower mechanical ventilation time and hospital or ICU mortality.36 37

In the overall or subgroup analyses in the present review, HFNC did not significantly reduce the incidence of PPCs or mortality compared with COT in postextubation surgical patients. These data are in contrast to a previous report, which speculated that HFNC may affect the outcomes of postoperative patients by alleviating PPCs.5

This systematic review and meta-analysis was associated with several limitations. First, not all included studies investigated reintubation rates and respiratory support escalation as primary endpoints, and most of the included studies were single-centre studies. Second, there were differences in the timing and duration of HFNC treatment and length of follow-up in the included studies. Third, the sample size was small; 3 out of 10 studies were non-RCTs, including less than 50 patients each. These limitations represent potential sources of bias and heterogeneity.

Conclusion

Findings from this review suggest that HFNC is associated with a significantly lower reintubation rate and rate of escalation of respiratory support compared with COT in postextubation adult surgical patients, but there is no difference in the incidence of PPCs or mortality. More well-designed, large randomised controlled trials are needed to determine the patient population that is most likely to benefit from HFNC therapy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ZL and FG had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis. ZL, S-SM, JX, HQ and FG performed the systematic review, study selection and statistical analysis. WC, J-YX, YY and XZ contributed to data extraction and the quality assessment. All authors participated in writing the article.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Project (2017ZX10103004), Key Laboratory of Environmental Medicine Engineering of Ministry of Education, Southeast University; National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: 81670074, 81471843, 81871602) and the projects of Jiangsu province’s medical key discipline (ZDXKA2016025). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: For information regarding this article, E-mail: fmguo2003@139.com.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Serpa Neto A, Hemmes SN, Barbas CS, et al. Incidence of mortality and morbidity related to postoperative lung injury in patients who have undergone abdominal or thoracic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2:1007–15. 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70228-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Melamed R, Boland LL, Normington JP, et al. Postoperative respiratory failure necessitating transfer to the intensive care unit in orthopedic surgery patients: risk factors, costs, and outcomes. Perioper Med 2016;5:19 10.1186/s13741-016-0044-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maggiore SM, Idone FA, Vaschetto R, et al. Nasal high-flow versus Venturi mask oxygen therapy after extubation. Effects on oxygenation, comfort, and clinical outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:282–8. 10.1164/rccm.201402-0364OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ricard JD. High flow nasal oxygen in acute respiratory failure. Minerva Anestesiol 2012;78:836–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ball L, Battaglini D, Pelosi P. Postoperative respiratory disorders. Curr Opin Crit Care 2016;22:379–85. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stéphan F, Barrucand B, Petit P, et al. High-Flow Nasal Oxygen vs Noninvasive Positive Airway Pressure in Hypoxemic Patients After Cardiothoracic Surgery. JAMA 2015;313:2331–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.5213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramirez A, Delord V, Khirani S, et al. Interfaces for long-term noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in children. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:655–62. 10.1007/s00134-012-2516-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zochios V, Collier T, Blaudszun G, et al. The effect of high-flow nasal oxygen on hospital length of stay in cardiac surgical patients at high risk for respiratory complications: a randomised controlled trial. Anaesthesia 2018;73:1478–88. 10.1111/anae.14345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hernández G, Vaquero C, Colinas L, et al. Effect of Postextubation High-Flow Nasal Cannula vs Noninvasive Ventilation on Reintubation and Postextubation Respiratory Failure in High-Risk Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;316:1565–74. 10.1001/jama.2016.14194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of Postextubation High-Flow Nasal Cannula vs Conventional Oxygen Therapy on Reintubation in Low-Risk Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:1354–61. 10.1001/jama.2016.2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corley A, Caruana LR, Barnett AG, et al. Oxygen delivery through high-flow nasal cannulae increase end-expiratory lung volume and reduce respiratory rate in post-cardiac surgical patients. Br J Anaesth 2011;107:998–1004. 10.1093/bja/aer265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Parke RL, McGuinness SP. Pressures delivered by nasal high flow oxygen during all phases of the respiratory cycle. Respir Care 2013;58:1621–4. 10.4187/respcare.02358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stéphan F, Barrucand B, Petit P, et al. High-Flow Nasal Oxygen vs Noninvasive Positive Airway Pressure in Hypoxemic Patients After Cardiothoracic Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2015;313:2331–9. 10.1001/jama.2015.5213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Song HZ, Gu JX, Xiu HQ, et al. The value of high-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy after extubation in patients with acute respiratory failure. Clinics 2017;72:562–7. 10.6061/clinics/2017(09)07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang BJ, Koh Y, Lim CM, et al. Failure of high-flow nasal cannula therapy may delay intubation and increase mortality. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:623–32. 10.1007/s00134-015-3693-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dhillon NK, Smith EJT, Ko A, et al. Extubation to high-flow nasal cannula in critically ill surgical patients. J Surg Res 2017;217:258–64. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parke R, McGuinness S, Dixon R, et al. Open-label, phase II study of routine high-flow nasal oxygen therapy in cardiac surgical patients. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:925–31. 10.1093/bja/aet262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Futier E, Paugam-Burtz C, Godet T, et al. Effect of early postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on hypoxaemia in patients after major abdominal surgery: a French multicentre randomised controlled trial (OPERA). Intensive Care Med 2016;42:1888–98. 10.1007/s00134-016-4594-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol 2010;25:603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheung MW, Ho RC, Lim Y, et al. Conducting a meta-analysis: basics and good practices. Int J Rheum Dis 2012;15:129–35. 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2012.01712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Corley A, Bull T, Spooner AJ, et al. Direct extubation onto high-flow nasal cannulae post-cardiac surgery versus standard treatment in patients with a BMI ≥30: a randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:887–94. 10.1007/s00134-015-3765-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu XP, Gao YF, Zhang BB. Evaluation of the effects of precautionary high-flow oxygen therapy in patients undergoing tracheal intubation after stanford type A aortic dissection. Chin J Nurs 2018;53:568–72. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu Y, Qian X, Liu C, et al. Effect of High-Flow Nasal Cannula versus Conventional Oxygen Therapy for Patients with Thoracoscopic Lobectomy after Extubation. Can Respir J 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/7894631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brainard J, Scott BK, Sullivan BL, et al. Heated humidified high-flow nasal cannula oxygen after thoracic surgery - A randomized prospective clinical pilot trial. J Crit Care 2017;40:225–8. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen Gj, Hy X, Pang H. Application of humidified high flow nasal cannula in respiratory failure patients post esophagectoy for esophageal cancer. J Crit Care 2018;38:301–4. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Geng XH. Application of nasal high-flow humidification oxygen therapy system in patients with acute respiratory failure after cardiothoracic surgery. Shandong Medical Journal 2016;56:94–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun T, Zhu HL. Clinical application of high- flow nasal cannula for the respiratory failure following radical resection of pulmonary carcinoma. Chin J Prac Nurs 2017;33:2335–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goligher EC, Slutsky AS. Not Just Oxygen? Mechanisms of Benefit from High-Flow Nasal Cannula in Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:1128–31. 10.1164/rccm.201701-0006ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Papazian L, Corley A, Hess D, et al. Use of high-flow nasal cannula oxygenation in ICU adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:1336–49. 10.1007/s00134-016-4277-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Testa G, Iodice F, Ricci Z, et al. Comparative evaluation of high-flow nasal cannula and conventional oxygen therapy in paediatric cardiac surgical patients: a randomized controlled trial. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;19:456–61. 10.1093/icvts/ivu171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spoletini G, Alotaibi M, Blasi F, et al. Heated Humidified High-Flow Nasal Oxygen in Adults: Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Implications. Chest 2015;148:253–61. 10.1378/chest.14-2871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang HW, Sun XM, Shi ZH, et al. Effect of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy Versus Conventional Oxygen Therapy and Noninvasive Ventilation on Reintubation Rate in Adult Patients After Extubation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Intensive Care Med 2018;33:885066617705118 10.1177/0885066617705118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu Y, Yin H, Zhang R, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy vs conventional oxygen therapy in cardiac surgical patients: A meta-analysis. J Crit Care 2017;38:123–8. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, et al. Effect of Conservative vs Conventional Oxygen Therapy on Mortality Among Patients in an Intensive Care Unit: The Oxygen-ICU Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;316:1583–9. 10.1001/jama.2016.11993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Helmerhorst HJ, Schultz MJ, van der Voort PH, et al. Effectiveness and Clinical Outcomes of a Two-Step Implementation of Conservative Oxygenation Targets in Critically Ill Patients: A Before and After Trial. Crit Care Med 2016;44:554–63. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027523supp001.jpg (40KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2018-027523supp002.jpg (64.9KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2018-027523supp003.jpg (146.4KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2018-027523supp004.pdf (410.9KB, pdf)