Abstract

Introduction

The aims of this program of research are to use linked health and law enforcement data to describe individuals presenting to emergency and inpatient healthcare services with an acute alcohol harm or problematic alcohol use; measure their health service utilisation and law enforcement engagement; and quantify morbidity, mortality, offending and incarceration.

Methods and analysis

We will assemble a retrospective cohort of people presenting to emergency departments and/or admitted to hospitals between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014 in New South Wales, Australia with a diagnosis denoting an acute alcohol harm or problematic alcohol use. We will link these data with records from other healthcare services (eg, community-based mental healthcare data, cancer registry), mortality, offending and incarceration data sets. The four overarching areas for analysis comprise: (1) describing the characteristics of the cohort at their first point of contact with emergency and inpatient hospital services in the study period with a diagnosis indicating an acute alcohol harm and/or problematic alcohol use; (2) quantifying health service utilisation and law enforcement engagement; (3) quantifying rates of mortality, morbidity, offending and incarceration; and (4) assessing predictors (eg, age, sex) of mortality, morbidity, offending and incarceration among this cohort.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been provided by the New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee. We will report our findings in accordance with the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data (RECORD) statement and Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) where appropriate. We will publish data in tabular, aggregate forms only. We will not disclose individual results. We will disseminate project findings at scientific conferences and in peer-reviewed journals. We will aim to present findings to relevant stakeholders (eg, addiction medicine and emergency medicine specialists, policy makers) to maximise translational impact of research findings.

Keywords: alcohol, data linkage, mortality, morbidity, incarceration, offending

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study comprises a population-based cohort of people with a diagnosis indicating an acute alcohol problem and/or problematic alcohol use (as identified through emergency department attendances and hospital separations) over an extended period (2005–2014).

There is a wealth of information on these participants through linkage to various routinely collected administrative data sets (ie, emergency department presentations, hospital separations, cancer notifications, mental health ambulatory care, mortality, offending and incarceration).

Routinely collected administrative data contain limited contextual information and represent an underestimate of total health and offending outcomes for these individuals (eg, where not brought to the attention of, and recorded by, these services).

Intervention and treatment for alcohol-related problems are not wholly captured across these data sources, and may impact experiences of morbidity, mortality, offending and incarceration.

The study period represents a snapshot for each individual; some individuals may have an extensive history of engagement with healthcare and law enforcement prior to entry to the cohort but this cannot necessarily be identified with the data used here.

Introduction

Reducing the health, social and economic burden of alcohol use is a priority in Australia and globally.1 2 Alcohol consumption is estimated to play a causal role in over 200 disease and injury conditions.2 Approximately 3.9% of deaths and 1.8% of hospitalisations in Australia are alcohol-related.3 Alcohol use negatively impacts on the community through reduced workplace productivity, traffic accidents, family problems, crime and public disorder, with an estimated economic cost of $14 billion annually.4

Recent evidence suggests declining population levels of consumption in Australia over the past two decades without clear evidence of a corresponding decrease in harms.5–9 Alcohol-related harms represent a significant burden on healthcare and law enforcement services. Indeed, recent estimates suggest that approximately one in ten emergency department presentations in Australia are alcohol-related,10 with more than 144,000 alcohol-attributable hospitalisations in Australia in 2012–2013.11

The aforementioned data are based on modelled estimates or on aggregated number of presentations to services. It is important to understand these events at the individual level: a significant proportion of people will have recurrent alcohol-related problems and experience substantial morbidity and higher risk of mortality as a consequence, placing a significant burden on healthcare and law enforcement services. In Australia, there has been no recent attempt at the population level to longitudinally track people with alcohol-related problems to measure overall mortality, morbidity and other problems (eg, offending and incarceration), despite such work for other substances (eg, opioids12).

This project, named the Data-Linkage Alcohol Cohort Study (DACS), will use data linkage to identify individuals presenting to emergency department or inpatient hospital services in NSW, Australia, with a diagnosis indicating an acute alcohol harm or problematic use. Records for this cohort of people will be linked to additional health and law enforcement service data for robust measurement of alcohol-related harms and burden. The overarching objectives of this program of research are to:

Describe the cohort at their first point of contact with emergency department or inpatient hospital services within the study period for an acute alcohol harm and/or problematic alcohol use;

Quantify healthcare service utilisation and law enforcement engagement among the cohort (and associated economic costs) and assess individual and situational characteristics as predictors of frequency of engagement;

Quantify the rate of mortality, morbidity, offending and incarceration among the cohort, looking at overall and cause-specific outcomes where possible; and

Assess individual and situational characteristics as predictors of mortality, morbidity, offending and incarceration.

Methods and analysis

Study design

This study will link two routinely collected administrative data sets from NSW, Australia, to assemble a retrospective observational cohort of people presenting to emergency department and hospital inpatient services with an acute alcohol harm and/or problematic alcohol use. Once the cohort has been identified, their linked data from other routinely collected administrative data sets will be extracted, providing information on emergency department presentations, hospital separations, cancer notifications, mental health ambulatory care, mortality, offending and incarceration. Data linkage will be undertaken by the Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL).

Formation of base cohort

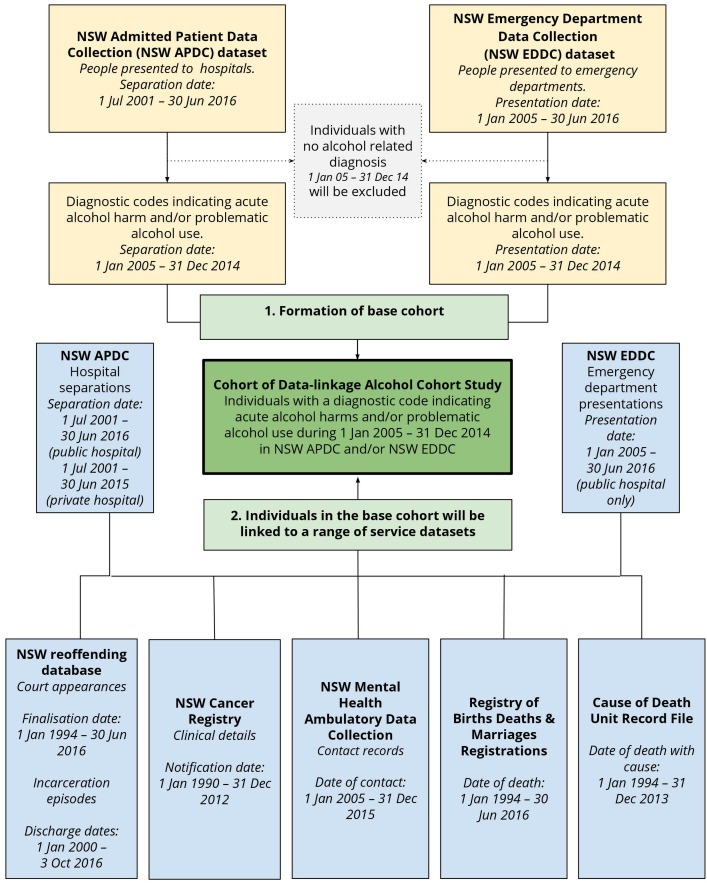

The base cohort will consist of individuals with a diagnosis indicating an acute alcohol harm or problematic alcohol use presenting to inpatient services (NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection; NSW APDC) and acute services (NSW Emergency Department Data Collection; NSW EDDC) in NSW between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2014. Diagnostic classification systems used by NSW APDC and NSW EDDC in this period comprise the International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems 9th Edition Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) or 10th edition Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM; NSW APDC and NSW EDDC) or the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms Australian Modification (SNOMED-CT-AU; NSW EDDC only). Diagnostic codes used for cohort inclusion were identified through a review of various sources on alcohol-related health burden and mortality (eg, Chikritzhs et al 13 and in consultation with specialists in the field (see table 1 for ICD-10-AM codes; see online supplementary appendix 1 for all the diagnosis codes used for cohort identification). A flow chart of how the base cohort will be formed and the administrative data sets to be linked (described in the next section) is presented in figure 1. Inclusion in the cohort may be modified depending on the specific research question being addressed.

Table 1.

Alcohol-related diagnosis codes used from ICD-10-AM

| Alcohol-related diagnosis | ICD-10-AM codes |

| Alcohol-induced pseudo-Cushing’s syndrome | E24.4 |

| Wernicke encephalopathy | E51.2 |

| Mental and behavioural disorders due to use of alcohol | F10 |

| Degeneration of nervous system due to alcohol | G31.2 |

| Alcoholic polyneuropathy | G62.1 |

| Alcoholic myopathy | G72.1 |

| Alcoholic cardiomyopathy | I42.6 |

| Alcoholic gastritis | K29.2 |

| Alcohol-induced liver diseases | K70.0, K70.1, K70.2, K70.3, K70.4, K70.9 |

| Alcohol-induced pancreatitis | K85.2, K86.0 |

| Maternal care for (suspected) damage to fetus from alcohol | O35.4 |

| Foetal alcohol syndrome (dysmorphic) | Q86.0 |

| Detection of alcohol in blood | R78.0, T51, X45, X65, Y15, Y90, Y91 |

Diagnostic classification systems used by NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC) and NSW Emergency Department Data Collection (EDDC) in this period comprise the International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems9th Edition Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) or the 10th Edition Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM; NSW APDC and NSW EDDC), or the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms Australian Modification (SNOMED-CT-AU; NSW EDDC only). Diagnostic codes used for cohort inclusion were identified through a review of various sources on alcohol-related health burden and mortality and in consultation with specialists in the field (see online supplementary appendix 1 for all the diagnosis codes used for data extraction).

Figure 1.

Formation of the Data-Linkage Cohort Study (DACS).

bmjopen-2019-030605supp001.pdf (353KB, pdf)

Data sets and linkage

On identifying the base cohort, the CHeReL will extract linked data for these individuals from a range of routinely collected administrative data sets using the probabilistic record linkage software ChoiceMaker.14 15 Identifying information (ie, name, address, date of birth and gender) for each data set is included in the Master Linkage Key (MLK) constructed by the CHeReL. The ChoiceMaker software uses an exact ‘blocking’ algorithm to search for valid matches in the MLK to identify all matching records. A combination of two techniques is used to determine whether each potential match denotes (or possibly denotes) the same person, comprising: (1) a probabilistic decision, which is computed using a machine learning technique, and (2) absolute rules, which include upper and lower probability cut-offs that initially start at 0.75 and 0.25 for a linkage and are adjusted for each individual linkage to ensure false links are minimised. The parameters for the extract from the MLK are set such that no true matches are missed if full identifiers are available. Extensive quality assurance measures ensure the false positive rate for linkage is less than 0.5% and the false negative rate for linkage is less than 0.1%.15 All data sets except the NSW Reoffending Database (ROD) are routinely contained within the MLK. The internal matching process of the NSW ROD has been validated (specificity of 99.9% and a sensitivity of 93.8%16), and linkage of records within the MLK to those within ROD will follow the same process as mentioned previously. Descriptions of the data sets for linkage are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Data sets for linkage

| Database | Description | Key variables |

| NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (APDC) | Records of all hospital separations (including discharges, transfers and deaths) from all public and private hospitals, public multipurpose services and day procedure centres in NSW. | Records for each episode of care include date of admission and separation, emergency status, principal and additional diagnoses, treatment procedures, mode of separation and facility identifier. |

| NSW Emergency Depatment Data Collection (EDDC) | Records of all presentations to emergency departments in major metropolitan and major non-metropolitan public hospitals in NSW. | Records for each episode of care include date of admission and separation, emergency status, diagnosis, mode of arrival and separation and facility identifier. |

| NSW Mental Health Ambulatory (NSW MH-AMB) Data Collection | Records of episodes of care delivered by NSW ambulatory mental health service units to non-admitted individuals, including day programmes, psychiatric outpatients and outreach services. | Records for each contact include date of contact, diagnosis and services delivered. Facility information includes provider group, provider role and service category and facility location. |

| NSW Central Cancer Registry (NSW CCR) | Records of all new cases of cancer (defined as an occurrence of a primary malignant neoplasm in an organ of a particular person; excluding occurrence of skin cancers other than melanoma) diagnosed in NSW residents. | Data include clinical details of individuals for example, cancer group, degree of spread, date and age of diagnosis. If applicable, information regarding date and age of death, and cause of death is also included. |

| NSW Reoffending Database (NSW ROD) | Court records, with all finalised court appearances in NSW Children’s, Local, District and Supreme Courts, and juvenile detention and adult incarceration in NSW. | Records include date and type of offence, outcome of court appearance, conviction date and penalty. Incarceration information includes commencement and conclusion date of incarceration, conviction date. |

| NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages (NSW RBDM) and the Australian Coordinating Registry Cause of Death Unit Record File (COD URF) | The two data sets contain mortality information for deaths occurring in NSW, which also includes ABS death registration data. The COD URF is held by the NSW Ministry of Health Secure Analytics for Population Health Research and Intelligence. | Data include date of death and contributing or multiple cause of death codes (where relevant). |

ABS, Australian Bureau of Statistics; ACR, Australian Coordinating Registry; APDC, Admitted Patients Data Collection; COD URF, Cause of Death Unit Record File; EDDC, Emergency Department Data Collection; MH-AMB, Mental Health Ambulatory Data Collection; NSW, New South Wales; RBDM, Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages; ROD, Reoffending Database.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of the study. As described in our dissemination activities (outlined below), we will aim to present findings to relevant stakeholders (eg, addiction medicine and emergency medicine specialists and policy makers) to maximise translational impact of research findings. We will prepare one-page summaries of key findings for distribution to drug treatment services and harm-reduction services.

Planned statistical analyses

We outline below the core analyses to address the overarching research questions. In all analyses, multiple confounding variables will be controlled as appropriate. We will also undertake the below analyses for the total cohort and focus specifically on young people (eg, aged 15–24 years old). This younger age demographic has demonstrated significant recent shifts in alcohol consumption alongside increasing harms,7 8 and also represents a portion of the sample likely to have no or limited engagement with healthcare and law enforcement services prior to the study period.

Aim 1. Describe the cohort at their first point of contact with emergency department or inpatient hospital services within the study period for an acute alcohol harm and/or problematic alcohol use.

We will describe the characteristics of the cohort at their index event (ie, first emergency department presentation or hospital separation with an alcohol-related diagnosis within the cohort period; diagnosis codes identified in online supplementary appendix 1). Our description will include the individual characteristics (eg, age, sex, socioeconomic status) and situational characteristics (eg, public or private hospital, diagnosis) of their presentation. We will analyse the 12-month period prior to each person’s index presentation to quantify existing health comorbidities (using an established comorbidity score, eg, Charlson Comorbidity Index17 or Elixhauser Comorbidity Index18), as well as offending and incarceration within that period. For these analyses, we will exclude individuals who had an index event within the first 12 months of the cohort commencement (ie, between 1 January and 31 December 2005) to provide capacity for analyses of the 12-month period prior to index presentation.

Aim 2. Quantify healthcare service utilisation and law enforcement engagement among the cohort (and associated economic costs) and assess individual and situational characteristics as predictors of frequency of engagement.

We will calculate total number of emergency department presentations and hospital separations each year, and number of unique people each year with an emergency department presentation/hospital separation with an alcohol-related diagnosis. We will estimate the number of hospital separations in two ways, as a count of episodes of care and of periods of stay.19 A period of stay will be defined as the complete period of care from admission to hospital until separation. A period of stay may consist of multiple episodes of care, the latter defined as a period of a specific care type (eg, receipt of acute care and rehabiliation may be coded as two episodes of care within one period of stay).

We will identify people who re-present to these services within 30 days of discharge (re-admission), as well as those individuals who attend at high-frequency (≥4 presentations/separations in a year) and high-intensity (average ≥4 presentations/separations in a year across period of follow-up or until death). We will use regression analyses to assess individual and situational characteristics of re-admission, high-frequency attendance and high-intensity attendance. We will quantify engagement with law enforcement (offending and incarceration). We will also estimate costs associated with health service utilisation and law enforcement engagement using standard reference material for costs (eg, Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Group codes for quantification of economic cost of hospital services20).

Aim 3. Quantify the rate of mortality, morbidity, offending and incarceration among the cohort, looking at overall rates and cause-specific outcomes where possible.

Aim 4. Assess individual and situational characteristics as predictors of mortality, morbidity, offending and incarceration.

Mortality analyses

We will calculate all-cause and cause-specific crude mortality rates as the number of deaths in the cohort divided by person-years of observation. We will estimate all-cause and cause-specific standardised mortality ratios by comparing the observed number of deaths and expected number of deaths. We will classify deaths in accordance with guidance for clustering major causes of mortality,21 with a focus on causes of death wholly or partly attributable to alcohol consumption.22 We will stratify crude mortality rates and standardised mortality ratios by other demographic and situational characteristics where possible based on population data (eg, age, geography, sex, comorbidity). We will conduct survival analyses to determine time from the index presentation to the outcome of interest (mortality or, if mortality does not occur, the censoring date) and use Cox proportional hazards regression to calculate hazard ratios for all-cause and cause-specific mortality based on time-independent (eg, gender) and time-dependent (eg, age, calendar year, geographic region, comorbidity score) variables.

Morbidity analyses

The main outcome of interest will be time (measured by the number of days) between presentations. Individuals will be censored at the end of the study period or date of death, whichever occurred first. We will use survival analysis methods that incorporate multiple observations per person23 to examine the relationship between risk factors (individual and situational characteristics at index) and the time interval distributions of recurrent presentations with multiple causes for each individual. We will examine any re-admission and alcohol-related re-admission, as well as time to specific type of alcohol-related re-admission (as defined in table 1). Risk factors will be identified for the entire cohort, adjusting for diagnostic groups. We will assess heterogeneity between diagnostic groups in the effect of risk factors descriptively. We will use the community-based Mental Health Ambulatory Data Collection (MH-AMB) to undertake a sub-group analysis of people with comorbid mental health issues.

Offending and incarceration analyses

To assess frequency of engagement with the criminal justice system among individuals with problematic use of alcohol, we will calculate rates of all offences and alcohol-related offences per 1000 person-years, as well as rates of incarceration episodes and time between offences (or death or end of follow-up, whichever comes first) distinguished by the characteristics of individuals (eg, gender). Offences will be classified in accordance with the Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification system24 (as per the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research standard crime statistics reporting25).

We will use survival analysis methods to examine the relationship between engagement with health services (characterised by number of alcohol-related presentations) and time to a subsequent arrest (days to any offence/days to alcohol-related offence). The hazard ratios for subsequent arrest will be adjusted for time-independent (eg, gender, country of birth) and time-dependent (eg, age, comorbidity score, calendar year, length of hospital stay, geographic region, private/public hospital, types of procedures undergone, remoteness, socioeconomic status) variables.

Methodological considerations

There are several key methodological considerations to be noted with the use of these data sets. First, the number of participating emergency departments has intermittently increased over time, from around 46 emergency departments in 1996 to around 90 in 2010226. There are around 150 emergency departments in NSW. Those servicing larger proportions of the NSW population are included but possible under-ascertainment of total engagement with emergency departments for alcohol-related problems should be noted. Where necessary, we will run analyses with and without the emergency departments that were added later in the series to establish if this has changed the study outcomes, with the aim of accounting for variable data quality from inclusion of new participating emergency departments in the EDDC. Second, variation in computer programs and management practices in emergency departments and hospitals may lead to variation in diagnosis coding practices (ie, ICD-9, ICD-10 and SNOMED codes entered by physicians) and in the screening and capture of alcohol involvement in healthcare presentations. Hence, the specificity of some disease categories may vary, and under-ascertainment of alcohol-related presentations is likely.27 Third, data on alcohol consumption, as well as intervention and treatment for problematic alcohol use, cannot be systematically ascertained from the included data sources. The NSW MH-AMB captures ambulatory mental health service provided to non-admitted individuals. To the authors’ knowledge, this data set has not been used to quantify engagement in prevention and intervention for alcohol-related problems in previous linkage studies. Until we have the capacity to study the data, we cannot know the quality of information provided; however, there may be the capacity to explore use of this data set to capture such engagement, and take this into consideration in analyses. Fourth, the false positive rate for linkage is less than 0.5% and the false negative rate for linkage is less than 0.1%.15 We will compare time-independent information (eg, date of birth, date of death) across data sets to identify inconsistencies that may be indicative of false positive linkages. These participants will be excluded from the cohort and identified in all reporting on final cohort composition. Finally, the study period represents a snapshot for each individual. Some individuals may have an extensive history of engagement with healthcare and law enforcement prior to entry into the cohort; this will be considered when drawing inferences from findings.

Ethics and dissemination

Data storage, retention and access

To protect privacy and confidentiality, approval for the linkage of health data in NSW is provided under strict conditions for the storage, retention and use of the data. The current approval permits storage of the data at three sites: the University of New South Wales, University of Queensland and University of Tasmania.

Ethics and dissemination

Data custodian approval has been granted and linkage and data cleaning have nearly been completed, with data analyses being performed and reporting occurring while the project retains ethical approval (currently until 2021). We will report our findings in accordance with the Reporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data statement (RECORD)28 and Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER),29 where appropriate. We will publish data in tabular, aggregate forms only and cells containing data from less than 10 participants will be suppressed. We will not disclose individual results.

We will disseminate project findings at scientific conferences and in peer-reviewed journals. We will aim to present findings to relevant stakeholders (eg, addiction medicine, emergency medicine, policy makers) to maximise translational impact of research findings.

Discussion

This program of research will provide a comprehensive population-level understanding of the burden of problematic alcohol use on individuals and on healthcare and law enforcement services. It will extend knowledge of individual and situational factors that predict adverse alcohol-related outcomes, with the capacity to inform personalised intervention. The patterns of healthcare utilisation will also improve our knowledge of patient needs to enhance healthcare delivery for targeted populations. The multidimensional measurement of diverse events produced by this project can better reflect the scale and impact of alcohol-related problems which may be under-ascertained in the study of a single data set.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Jürgen Rehm for his input on the diagnostic codes chosen and Professor Adrian Dunlop for his input on study design. We wish to thank the Clinical Terminology Team at the National E-Health Transition Authority (now the Australian Digital Health Agency) for assisting with mapping International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) codes to Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms Australian Modification (SNOMED-CT-AU). We also wish to thank the New South Wales (NSW) Ministry of Health, the Centre for Health Record Linkage, the Cancer Institute NSW and other data custodians for reviewing the project protocol, approving the project and providing requested data. The Cause of Death Unit Record File (COD URF) is provided by the Australian Coordinating Registry for the COD URF on behalf of the NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, NSW Coroner and the National Coronial Information System.

Footnotes

Contributors: AP and LD conceived the study idea. AP, LD, TD, NG, SL, and SAP provided input to the study design and research questions. AP, TD, VC and JL developed the statistical analysis plan. AP, VC and JL completed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided input to the final draft.

Funding: This work was funded by research support funds awarded by University of New South Wales (UNSW), Sydney to AP. AP, SL and LD are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council research fellowships (#1109366, #1140938 and #1041472/#1135991). SL and NG are supported by UNSW Scientia Fellowships. SL and LD are supported by National Institutes of Health grant NIDA R01DA1104470. The National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre is supported by funding from the Australian Government Department of Health under the Drug and Alcohol Program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by New South Wales Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee in August 2016 (2016/08/650).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Australian Government Department of Health. National Drug Strategy 2017-2016. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gao C, Ogeil RP, Lloyd B. Alcohol’s burden of disease in Australia. Canberra: Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and VicHealth in collaboration with Turning Point, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manning M, Smith C, Mazerolle P. The societal costs of alcohol misuse in Australia. Trends & issues in crime and criminal justice No. 454. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Livingston M. Understanding recent trends in Australian alcohol consumption. Canberra: Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Livingston M, Matthews S, Barratt MJ, et al. Diverging trends in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:368–73. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Livingston M. Recent trends in risky alcohol consumption and related harm among young people in Victoria, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:266–71. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Callinan S, Pennay A, Livingston M, et al. Patterns in Reduction or Cessation of Drinking in Australia (2001–2013) and Motivation for Change. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2018;54:79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Livingston M, Callinan S, Raninen J, et al. Alcohol consumption trends in Australia: Comparing surveys and sales-based measures. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018;37:S9–S14. 10.1111/dar.12588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Egerton-Warburton D, Gosbell A, Moore K, et al. Alcohol-related harm in emergency departments: a prospective, multi-centre study. Addiction 2018;113:623–32. 10.1111/add.14109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lensvelt E, Gilmore W, Liang W, et al. Estimated alcohol-attributable deaths and hospitalisations in Australia 2004 to 2015. National Alcohol Indicators, Bulletin 16. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Degenhardt L, Larney S, Kimber J, et al. The impact of opioid substitution therapy on mortality post-release from prison: retrospective data linkage study. Addiction 2014;109:1306–17. 10.1111/add.12536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Stockwell T, et al. Australian alcohol indicators, 1990-2001: Patterns of alcohol use and related harms for Australian states and territories. Perth: National Drug Research Institute, Curtin University, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Key Concepts of the ChoiceMaker 2 Record Matching System [program] Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lawrence G, Dinh I, Taylor L. The centre for health record linkage: a new resource for health services research and evaluation. Health Inf Manag 2008;37:60–2. 10.1177/183335830803700208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hua J, Fitzgerald J. Matching court records to measure reoffending. BOCSAR NSW Crime and Justice Bulletins 2006;12. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, et al. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245–51. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. AIHW. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare - Hospitals Glossary. 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/health-welfare-services/hospitals/glossary

- 20. Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG). Classification Version 8.0 Australian Consortium for Classification Development. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Randall D, Roxburgh A, Gibson A, et al. Mortality among people who use illicit drugs: A toolkit for classifying major causes of death. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of NSW, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roerecke M, Rehm J. Cause-specific mortality risk in alcohol use disorder treatment patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:906–19. 10.1093/ije/dyu018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amorim LD, Cai J. Modelling recurrent events: a tutorial for analysis in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:324–33. 10.1093/ije/dyu222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pink B. Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC). 3rd edn: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25. AIHW. Australian and New Zealand Standard Offence Classification (ANZSOC). Cat. no. 1234.0, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26. NSW Ministry of Health. NSW Emergency Department Data Collection: Data Dictionary. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. McKenzie K, Harrison JE, McClure RJ. Identification of alcohol involvement in injury-related hospitalisations using routine data compared to medical record review. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:146–52. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001885 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet 2016;388:e19–e23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30388-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030605supp001.pdf (353KB, pdf)