Introduction

Helicobacter pylori is a bacterium that infects the mucus gel layer above the gastric epithelium in approximately half of the world’s population [1]. Infection with H. pylori causes gastritis, which may become chronic. Chronic inflammation of the stomach mucosa leads to morphological changes in the gastric epithelium transitioning from chronic atrophic gastritis to intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and, in 1%–3% of H. pylori–infected individuals, to gastric cancer [2]. This progression from normal to cancerous tissue takes decades and can be inhibited by eradication of the bacterium through antibiotic treatment [2]. Besides causing gastric cancer, which was officially acknowledged by the World Health Organization in 1994 [3], the presence of H. pylori has been associated with other diseases as well. Within the stomach, H. pylori increases risk of peptic ulcer and lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphatic tissues; outside of the stomach, H. pylori has been found to be associated with not only a range of noncancerous diseases, including asthma, Parkinson, and diabetes, but also other cancerous outcomes in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly the colorectum [4, 5].

Epidemiological findings

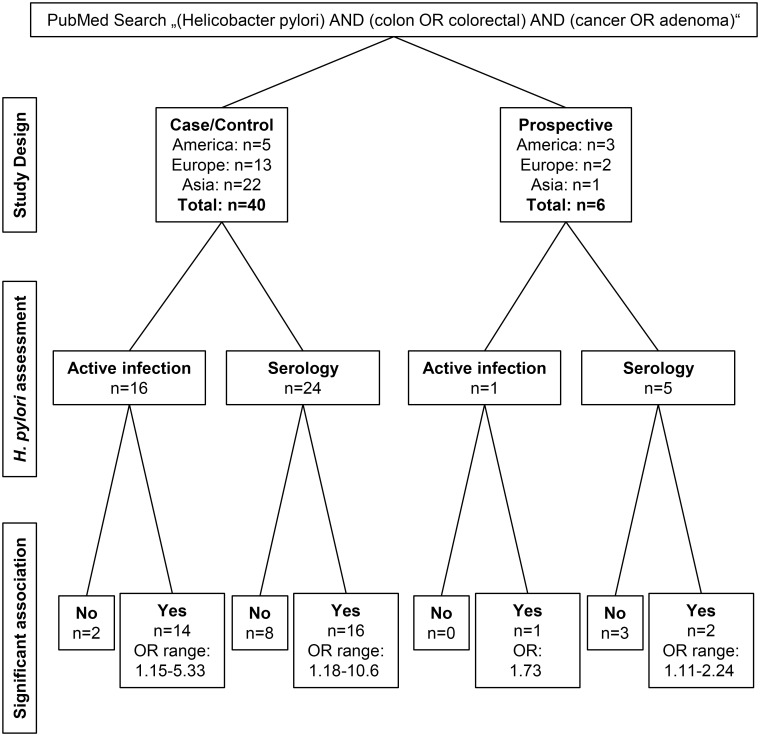

Numerous studies have addressed the potential association of H. pylori infection with colorectal cancer (CRC) and precancerous lesions. In a PubMed search on the terms “(Helicobacter pylori) AND (colon OR colorectal) AND (cancer OR adenoma)”we found 40 case-control and six prospective studies (Fig 1) [6–51]. The majority of case-control studies (n = 22) were conducted in Asia, an area with a high burden of H. pylori infection [6, 7, 11, 18, 24–26, 28–33, 35, 39–42, 44, 46, 50, 51]. Screening programs for gastric cancer in certain Asian countries include esophagogastroduodenoscopy on a regular basis, which allows assessing H. pylori infection and severity of tissue damage directly from stomach biopsies to compare with the outcome of concomitant colonoscopies. This direct approach assesses active H. pylori infection, an advantage to serology. Independent of the method applied, however, the majority of case-control studies (n = 30) reported a positive association of H. pylori with colorectal adenoma and/or cancer prevalence, with odds ratios varying between 1.15 and 10.6 [6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 16–18, 21–35, 37–40, 42, 46, 51]. A meta-analysis by Wu and colleagues (2013) reported a summary estimate of 1.66 (95% confidence interval: 1.30–1.97) for colorectal adenoma and 1.39 (95% confidence interval: 1.18–1.64) for CRC [52], which reflects reported results from the majority of case-control studies cited in this review.

Fig 1. Original articles on H. pylori and colorectal adenoma and cancer published through March 2019 in PubMed.

A PubMed literature search was performed to identify case-control and prospective studies assessing the association of H. pylori infection with colorectal adenoma and/or cancer. Identified studies varied by geographical region (America, Europe, Asia) and method to diagnose H. pylori infection (direct detection of active infection by urea breath test, gastric biopsy, and/or H. pylori–related gastric disease versus serology as an indirect measure of past and current infection).

In the six prospective studies identified [10, 13, 14, 19, 20, 48], three were performed in the United States and analyzed samples from different races/ethnicities. Interestingly, among white populations, there was no increased risk of CRC with seropositivity to H. pylori, whereas significant increases in risk were reported among African Americans [10, 14, 20]. The serological method applied in these three studies was multiplex serology, an assay that allows the analysis of antibody responses to specific H. pylori proteins as opposed to general H. pylori seropositivity [53]. African Americans were reported to be at an approximately 2-fold increased risk of developing CRC with antibody responses to an H. pylori toxin, Vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) [10, 20]. This association was even reported with a dose–response relationship in terms of higher level of antibody response, which may signal a more severe infection with H. pylori in the stomach, being more strongly associated with CRC risk.

In summary, epidemiological findings in the literature hint toward a relation of H. pylori infection with CRC risk. However, whether this is a causal relationship and what the potential mechanisms are, as explained below, still need to be identified.

Causality?—A question yet to be solved

As laid out above, the natural habitat of H. pylori infection is the stomach. Thus, the question that arises is whether the observed association of H. pylori with cancer in the colon could be due to a causal relationship. The positive associations in prospective studies suggest that reverse causality is not responsible for this association; however, it cannot be ruled out that other factors are the underlying reason for the reported observations. For example, H. pylori prevalence is generally associated with lower socioeconomic status worldwide [54, 55]. H. pylori infection is usually acquired in childhood, and living conditions during childhood, including household crowding, have been reported to be associated with H. pylori prevalence among adults [56]. The association observed between socioeconomic status and H. pylori in adults, however, could also relate to access to healthcare, a factor that also correlates with access to CRC screening. In our recently published study on H. pylori serology and CRC risk in diverse populations in the US, however, education, as a proxy for socioeconomic status, was not associated with risk of CRC and moreover did not confound the association of H. pylori with CRC, suggesting that low socioeconomic status is not a significant cause of the associations seen between H. pylori infection and increased CRC risk [10].

Intriguingly, CRC incidence and H. pylori prevalence coincide by population. From 2002 to 2012, an increase in CRC incidence was observed in China, Spain, and countries in Eastern Europe [57], countries that also report the highest H. pylori prevalence worldwide [1]. Furthermore, taking the US as an example, although the overall CRC incidence has been declining over the past decades, incidence rates are still 10%–20% higher in Alaskan Natives and African Americans as opposed to whites [58], and again, this coincides with a notable disparity in H. pylori prevalence [54]. As mentioned above, the observed associations were not confounded by educational level [10, 20]. Nevertheless, the association still may be affected by other cofactors including lifestyle, comorbidities, medications, and host response to the infecting bacterial strain [58, 59].

A recent study by Hu and colleagues (2018), conducted in Taiwan, further supports a causal relationship between persistent H. pylori infection and CRC development [60]. The authors follow up individuals with either no H. pylori infection, successful H. pylori eradication, or persistent H. pylori infection for the development of colorectal adenoma. The incidence rates of adenoma in the noninfected and eradicated group were comparable in the follow-up time period of 9 years, whereas the incidence rate in the group with persistent infection was 3-fold higher. Information on whether persistent infection was a consequence of antibiotic resistance, noncompliance to the applied antibiotic treatment, or reinfection during the study course was not further specified in the publication. Moreover, it would have been interesting to further define whether persistent H. pylori infection alone or together with associated epithelial damage in the stomach—such as atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, or even gastric cancer—was associated with colorectal adenoma incidence. And, as the authors conclude, the mechanisms of this potential causal relation still need to be elucidated.

Potential mechanisms for a causal relationship

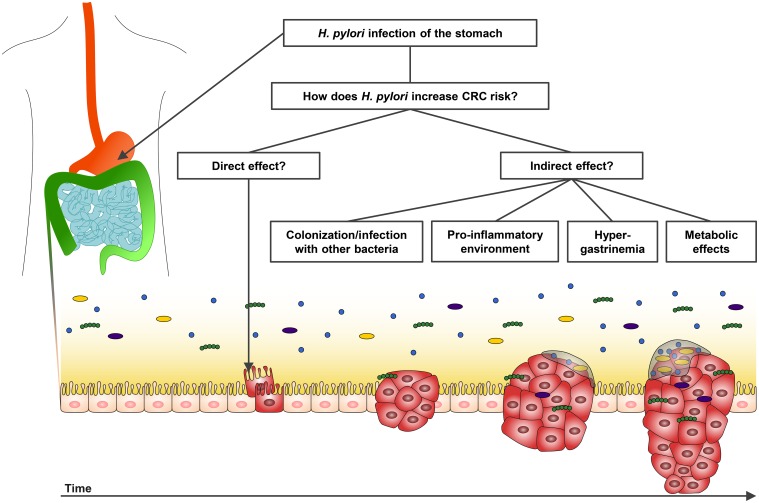

If causal, H. pylori could have direct and/or indirect effects on colorectal carcinogenesis (Fig 2). A direct effect would involve the bacterium or molecular effectors, like secreted toxins, to be present in the respective colorectal tissue. Very few studies have addressed the presence of H. pylori in colorectal tumor tissue by PCR or histology [61–63]. Two case series found H. pylori in 22%–27% of analyzed colorectal polyps or cancers [61, 63]. A case-control study found positive H. pylori histology in tumor tissue of 19 out of 118 cases, whereas only one out of 58 controls were H. pylori tissue positive in the colon [62]. These findings plus the fact that a diagnostic test uses the presence of H. pylori antigen in stool lead to the assumption that H. pylori or constituents of it at least traverse the colon. Larger studies with normal tissue and tissue from all stages along the carcinogenic process in the colorectum are needed to confirm this hypothesis. It furthermore needs to be elucidated if and how H. pylori might then be able to elicit carcinogenic effects in the colorectum.

Fig 2. Potential mechanisms for causal effect(s) of H. pylori on colorectal carcinogenesis.

The natural site of H. pylori infection is the stomach. Thus, the question arises how and when in the process from a healthy gut epithelium to CRC H. pylori might contribute to carcinogenesis. Besides a potential direct effect, H. pylori might exert indirect effects through enabling other bacteria to colonize/infect the colorectal epithelium and/or by causing systemic pro-inflammatory, hormonal, or metabolic changes. CRC, colorectal cancer.

Under the assumption that H. pylori might not be able to infect the colorectal epithelium, there are several hypotheses as to how H. pylori could indirectly contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis. First, H. pylori infection could lead to changes in the colonization of the gut with other bacteria that in turn could contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis. A study by Gao and colleagues (2018), found that the gut microbiome composition did not differ between H. pylori–infected and –noninfected individuals but did differ by H. pylori–related gastric lesion—i.e., between H. pylori–infected individuals with normal, gastritis, and metaplastic tissue [64]. As described above, several case-control studies found higher odds for colorectal adenoma and cancer in individuals with H. pylori–related gastric lesion compared with healthy controls [11, 35, 39, 42].

Second, H. pylori infection could be involved in colorectal carcinogenesis by increasing the release of gastrin that may act as a mitogen. It has been shown that H. pylori induces hypergastrinemia; however, studies on the interplay of H. pylori infection, gastrin level, and CRC report inconclusive results and therefore need further investigation [15, 17, 23, 43, 44, 47]. Similarly, H. pylori was found to be associated with metabolic diseases that in turn were also described to be associated with CRC risk. The analyses of a combined effect of these with H. pylori on colorectal carcinogenesis are, however, also inconclusive. We found one case-control study that reported significant independent associations of metabolic syndrome and H. pylori with colorectal adenoma prevalence [32], as opposed to another study that found a combined increased association of H. pylori and diabetes with colorectal adenoma prevalence [6].

Finally, H. pylori induces chronic inflammation in the stomach mucosa, thereby also elevating systemically inflammatory responses in the body [65, 66]. Inflammation is reported to be associated with an increased CRC risk, and similarly, long-term intake of aspirin as an anti-inflammatory drug was shown to protect from CRC development [67]. It is unknown, though, whether H. pylori might create a pro-inflammatory state in the gastrointestinal tract that may increase CRC risk.

Comprehensive longitudinal studies are needed to address the interaction and temporality of the abovementioned potential mediators with the association of H. pylori and CRC risk. Furthermore, all of the abovementioned possibilities do not have to be exclusive mechanisms but, rather, most likely interact.

Conclusion

There is growing evidence for H. pylori infection increasing CRC risk. A causal relationship and the mechanism behind this bacterium potentially acting abroad from its natural habitat, the stomach, however, still need to be clarified. If proven to be causal, with a direct and/or indirect pathway, H. pylori eradication might be an effective strategy to help prevent CRC development in a subset of cases. Independent of a causal relationship, the knowledge of the association of H. pylori and CRC risk could help to define more rigid CRC screening programs for H. pylori–positive individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew G. Varga for the fruitful discussions on H. pylori biology and Jan-Eric Meissner for his support in design of the figures.

Funding Statement

This manuscript was supported by funding from NIH R01CA190428. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correa P, Houghton J. Carcinogenesis of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):659–72. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.026 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 7–14 June 1994. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans / World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschi F, Gasbarrini A, Polyzos SA, Kountouras J. Extragastric Diseases and Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2015;20 Suppl 1:40–6. 10.1111/hel.12256 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venerito M, Vasapolli R, Rokkas T, Delchier JC, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori, gastric cancer and other gastrointestinal malignancies. Helicobacter. 2017;22 Suppl 1 10.1111/hel.12413 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu KC, Wu MS, Chu CH, Wang HY, Lin SC, Liu SC, et al. Synergistic Effect of Hyperglycemia and Helicobacterpylori Infection Status on Colorectal Adenoma Risk. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2017;102(8):2744–50. 10.1210/jc.2017-00257 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park YM, Kim HS, Park JJ, Baik SJ, Youn YH, Kim JH, et al. A simple scoring model for advanced colorectal neoplasm in asymptomatic subjects aged 40–49 years. BMC gastroenterology. 2017;17(1):7 10.1186/s12876-016-0562-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siddheshwar RK, Muhammad KB, Gray JC, Kelly SB. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with colorectal polyps and colorectal carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):84–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buso AG, Rocha HL, Diogo DM, Diogo PM, Diogo-Filho A. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with colon adenomas in a Brazilian university hospital. Arq Gastroenterol. 2009;46(2):97–101. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butt J, Varga MG, Blot WJ, Teras L, Visvanathan K, Le Marchand L, et al. Serologic Response to Helicobacter pylori Proteins Associated With Risk of Colorectal Cancer Among Diverse Populations in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):175–86 e2. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.09.054 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tongtawee T, Simawaranon T, Wattanawongdon W. Role of screening colonoscopy for colorectal tumors in Helicobacter pylori-related chronic gastritis with MDM2 SNP309 G/G homozygous: A prospective cross-sectional study in Thailand. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2018;29(5):555–60. 10.5152/tjg.2018.17608 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shmuely H, Passaro D, Figer A, Niv Y, Pitlik S, Samra Z, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori CagA status and colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(12):3406–10. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu WY, Lin CH, Lin CC, Sung FC, Hsu CP, Kao CH. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori and cancer risk. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(3):235–40. 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.01.009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blase JL, Campbell PT, Gapstur SM, Pawlita M, Michel A, Waterboer T, et al. Prediagnostic Helicobacter pylori Antibodies and Colorectal Cancer Risk in an Elderly, Caucasian Population. Helicobacter. 2016;21(6):488–92. 10.1111/hel.12305 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgopoulos SD, Polymeros D, Triantafyllou K, Spiliadi C, Mentis A, Karamanolis DG, et al. Hypergastrinemia is associated with increased risk of distal colon adenomas. Digestion. 2006;74(1):42–6. 10.1159/000096593 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meucci G, Tatarella M, Vecchi M, Ranzi ML, Biguzzi E, Beccari G, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with colonic adenomas and carcinomas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25(4):605–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fireman Z, Trost L, Kopelman Y, Segal A, Sternberg A. Helicobacter pylori: seroprevalence and colorectal cancer. The Israel Medical Association journal: IMAJ. 2000;2(1):6–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam KW, Baeg MK, Kwon JH, Cho SH, Na SJ, Choi MG. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity is positively associated with colorectal neoplasms. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2013;61(5):259–64. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Limburg PJ, Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Colbert LH, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, Taylor PR, et al. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and colorectal cancer risk: a prospective study of male smokers. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2002;11(10 Pt 1):1095–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epplein M, Pawlita M, Michel A, Peek RM Jr., Cai Q, Blot WJ. Helicobacter pylori protein-specific antibodies and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2013;22(11):1964–74. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0702 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Helicobacter pylori is a risk factor for colonic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):208–15. 10.1038/ajg.2012.407 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zumkeller N, Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Hoffmeister M, Nieters A, Rothenbacher D. Helicobacter pylori infection, interleukin-1 gene polymorphisms and the risk of colorectal cancer: evidence from a case-control study in Germany. European journal of cancer. 2007;43(8):1283–9. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.03.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartwich A, Konturek SJ, Pierzchalski P, Zuchowicz M, Labza H, Konturek PC, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection, gastrin, cyclooxygenase-2, and apoptosis in colorectal cancer. International journal of colorectal disease. 2001;16(4):202–10. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan Y, Chen YN, Zhao Q, Chen C, Lin CJ, Jin Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection with intestinal metaplasia: An independent risk factor for colorectal adenomas. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2017;23(8):1443–9. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i8.1443 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JY, Park HW, Choi JY, Lee JS, Koo JE, Chung EJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection with Atrophic Gastritis Is an Independent Risk Factor for Advanced Colonic Neoplasm. Gut Liver. 2016;10(6):902–9. 10.5009/gnl15340 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuno S, Morita Y, Inui T, Asakawa A, Ueno N, Ando T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with colon adenomatous polyps detected by high-resolution colonoscopy. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2005;117(6):1058–9. 10.1002/ijc.21280 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shmuely H, Melzer E, Braverman M, Domniz N, Yahav J. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with advanced colorectal neoplasia. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2014;49(1):35–42. 10.3109/00365521.2013.848468 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim TJ, Kim ER, Chang DK, Kim YH, Baek SY, Kim K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is an independent risk factor of early and advanced colorectal neoplasm. Helicobacter. 2017;22(3). 10.1111/hel.12377 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nam JH, Hong CW, Kim BC, Shin A, Ryu KH, Park BJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is an independent risk factor for colonic adenomatous neoplasms. Cancer causes & control: CCC. 2017;28(2):107–15. 10.1007/s10552-016-0839-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong SN, Lee SM, Kim JH, Lee TY, Kim JH, Choe WH, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection increases the risk of colorectal adenomas: cross-sectional study and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(8):2184–94. 10.1007/s10620-012-2245-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujimori S, Kishida T, Kobayashi T, Sekita Y, Seo T, Nagata K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection increases the risk of colorectal adenoma and adenocarcinoma, especially in women. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(9):887–93. 10.1007/s00535-005-1649-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin YL, Chiang JK, Lin SM, Tseng CE. Helicobacter pylori infection concomitant with metabolic syndrome further increase risk of colorectal adenomas. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2010;16(30):3841–6. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i30.3841 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ChangxiChen, Mao Y, Du J, Xu Y, Zhu Z, Cao H. Helicobacter pylori infection associated with an increased risk of colorectal adenomatous polyps in the Chinese population. BMC gastroenterology. 2019;19(1):14 10.1186/s12876-018-0918-4 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Hoffmeister M, Weck MN, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection and colorectal cancer risk: evidence from a large population-based case-control study in Germany. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;175(5):441–50. 10.1093/aje/kwr331 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tongtawee T, Kaewpitoon S, Kaewpitoon N, Dechsukhum C, Leeanansaksiri W, Loyd RA, et al. Helicobacter Pylori Associated Gastritis Increases Risk of Colorectal Polyps: a Hospital Based-Cross-Sectional Study in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Northeastern Thailand. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2016;17(1):341–5. 10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.1.341 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernandez de Larrea-Baz N, Michel A, Romero B, Perez-Gomez B, Moreno V, Martin V, et al. Helicobacter pylori Antibody Reactivities and Colorectal Cancer Risk in a Case-control Study in Spain. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017;8:888 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00888 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breuer-Katschinski B, Nemes K, Marr A, Rump B, Leiendecker B, Breuer N, et al. Helicobacter pylori and the risk of colonic adenomas. Colorectal Adenoma Study Group. Digestion. 1999;60(3):210–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brim H, Zahaf M, Laiyemo AO, Nouraie M, Perez-Perez GI, Smoot DT, et al. Gastric Helicobacter pylori infection associates with an increased risk of colorectal polyps in African Americans. BMC cancer. 2014;14:296 10.1186/1471-2407-14-296 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae RC, Jeon SW, Cho HJ, Jung MK, Kweon YO, Kim SK. Gastric dysplasia may be an independent risk factor of an advanced colorectal neoplasm. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2009;15(45):5722–6. 10.3748/wjg.15.5722 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inoue I, Mukoubayashi C, Yoshimura N, Niwa T, Deguchi H, Watanabe M, et al. Elevated risk of colorectal adenoma with Helicobacter pylori-related chronic gastritis: a population-based case-control study. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2011;129(11):2704–11. 10.1002/ijc.25931 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang KX, Wang XF, Peng JL, Cui YB, Wang J, Li CP. Detection of serum anti-Helicobacter pylori immunoglobulin G in patients with different digestive malignant tumors. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2003;9(11):2501–4. 10.3748/wjg.v9.i11.2501 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qing Y, Wang M, Lin YM, Wu D, Zhu JY, Gao L, et al. Correlation between Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric diseases and colorectal neoplasia. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2016;22(18):4576–84. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i18.4576 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Onghia V, Leoncini R, Carli R, Santoro A, Giglioni S, Sorbellini F, et al. Circulating gastrin and ghrelin levels in patients with colorectal cancer: correlation with tumour stage, Helicobacter pylori infection and BMI. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy. 2007;61(2–3):137–41. 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.08.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Machida-Montani A, Sasazuki S, Inoue M, Natsukawa S, Shaura K, Koizumi Y, et al. Atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori, and colorectal cancer risk: a case-control study. Helicobacter. 2007;12(4):328–32. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00513.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abbass K, Gul W, Beck G, Markert R, Akram S. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with the development of colorectal polyps and colorectal carcinoma. South Med J. 2011;104(7):473–6. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31821e9009 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teimoorian F, Ranaei M, Hajian Tilaki K, Shokri Shirvani J, Vosough Z. Association of Helicobacter pylori Infection With Colon Cancer and Adenomatous Polyps. Iran J Pathol. 2018;13(3):325–32. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strofilas A, Lagoudianakis EE, Seretis C, Pappas A, Koronakis N, Keramidaris D, et al. Association of helicobacter pylori infection and colon cancer. J Clin Med Res. 2012;4(3):172–6. 10.4021/jocmr880w . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen XZ, Schottker B, Castro FA, Chen H, Zhang Y, Holleczek B, et al. Association of helicobacter pylori infection and chronic atrophic gastritis with risk of colonic, pancreatic and gastric cancer: A ten-year follow-up of the ESTHER cohort study. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):17182–93. 10.18632/oncotarget.7946 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel S, Lipka S, Shen H, Barnowsky A, Silpe J, Mosdale J, et al. The association of H. pylori and colorectal adenoma: does it exist in the US Hispanic population? J Gastrointest Oncol. 2014;5(6):463–8. 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2014.074 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu IC, Wu DC, Yu FJ, Wang JY, Kuo CH, Yang SF, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and digestive tract cancers. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2009;15(43):5465–71. 10.3748/wjg.15.5465 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park H, Park JJ, Park YM, Baik SJ, Lee HJ, Jung DH, et al. The association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of advanced colorectal neoplasia may differ according to age and cigarette smoking. Helicobacter. 2018;23(3):e12477 10.1111/hel.12477 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu Q, Yang ZP, Xu P, Gao LC, Fan DM. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2013;15(7):e352–64. 10.1111/codi.12284 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Michel A, Waterboer T, Kist M, Pawlita M. Helicobacter pylori multiplex serology. Helicobacter. 2009;14(6):525–35. Epub 2009/11/06. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00723.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjomina O, Pavlova J, Niv Y, Leja M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23 Suppl 1:e12514 10.1111/hel.12514 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khalifa MM, Sharaf RR, Aziz RK. Helicobacter pylori: a poor man’s gut pathogen? Gut pathogens. 2010;2(1):2 10.1186/1757-4749-2-2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mendall MA, Goggin PM, Molineaux N, Levy J, Toosy T, Strachan D, et al. Childhood living conditions and Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in adult life. Lancet. 1992;339(8798):896–7. 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90931-r . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66(4):683–91. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(3):177–93. 10.3322/caac.21395 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nedelec Y, Sanz J, Baharian G, Szpiech ZA, Pacis A, Dumaine A, et al. Genetic Ancestry and Natural Selection Drive Population Differences in Immune Responses to Pathogens. Cell. 2016;167(3):657–69 e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu KC, Wu MS, Chu CH, Wang HY, Lin SC, Liu CC, et al. Decreased Colorectal Adenoma Risk after Helicobacter pylori Eradication: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018. 10.1093/cid/ciy591 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grahn N, Hmani-Aifa M, Fransen K, Soderkvist P, Monstein HJ. Molecular identification of Helicobacter DNA present in human colorectal adenocarcinomas by 16S rDNA PCR amplification and pyrosequencing analysis. Journal of medical microbiology. 2005;54(Pt 11):1031–5. 10.1099/jmm.0.46122-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones M, Helliwell P, Pritchard C, Tharakan J, Mathew J. Helicobacter pylori in colorectal neoplasms: is there an aetiological relationship? World journal of surgical oncology. 2007;5:51 10.1186/1477-7819-5-51 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soylu A, Ozkara S, Alis H, Dolay K, Kalayci M, Yasar N, et al. Immunohistochemical testing for Helicobacter Pylori existence in neoplasms of the colon. BMC gastroenterology. 2008;8:35 10.1186/1471-230X-8-35 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao JJ, Zhang Y, Gerhard M, Mejias-Luque R, Zhang L, Vieth M, et al. Association Between Gut Microbiota and Helicobacter pylori-Related Gastric Lesions in a High-Risk Population of Gastric Cancer. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2018;8:202 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00202 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jackson L, Britton J, Lewis SA, McKeever TM, Atherton J, Fullerton D, et al. A population-based epidemiologic study of Helicobacter pylori infection and its association with systemic inflammation. Helicobacter. 2009;14(5):108–13. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00711.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Siregar G, Halim S, Sitepu R. Serum IL-10, MMP-7, MMP-9 Levels in Helicobacter pylori Infection and Correlation with Degree of Gastritis. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2016;4(3):359–63. 10.3889/oamjms.2016.099 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383(9927):1490–502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]