Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate the effect of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on US veterans’ access to care.

Methods. We used US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data to compare measures of veterans’ coverage and access to care, including primary care, for 3-year periods before (2011–2013) and after (2015–2017) ACA coverage provisions went into effect. We used difference-in-differences analyses to compare changes in Medicaid expansion states with those in nonexpansion states.

Results. Coverage increased and fewer delays in care were reported in both expansion and nonexpansion states after 2014, with larger effects among low socioeconomic status (SES) and poor health subgroups. Coverage increases were significantly larger in expansion states than in nonexpansion states. Reports of cost-related delays, no usual source of care, and no checkup within 12 months generally improved in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states, but improvements were small; changes were mixed among veterans with low SES or poor health.

Conclusions. Increases in insurance coverage among nonelderly veterans after ACA coverage expansions did not consistently translate into improved access to care. Additional study is needed to understand persisting challenges in veterans’ access to care.

Access to timely, high-quality health care is a broadly accepted policy goal for veterans in the United States. Yet fewer than half of approximately 20 million veterans nationwide are enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), with many ineligible for VHA care or US Department of Veterans Affairs financial assistance.1 Those not enrolled seek insurance coverage through private health plans or government programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid. But many veterans fall through the cracks; before 2014, approximately 1 million veterans lacked any health insurance coverage. Therefore, coverage expansions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA; Pub L No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 855 [March 2010]) offered a unique opportunity to affect veterans’ coverage and access to care.2

Since the ACA coverage provisions took effect, the numbers of uninsured nonelderly adults and nonelderly veterans have both decreased by more than one third—from 16.7% to 10.6% for all nonelderly adults and from 9.6% to 5.9% for veterans.3–5 However, whether these policies have led to improved access to care for veterans has not previously been reported.

We sought to determine changes in veterans’ coverage and access to care before and after ACA coverage provisions went into effect in 2014 and compared changes in states that expanded Medicaid with changes in states that did not. We hypothesized that health care access would improve and correlate with insurance coverage gains, as has been observed in the general population.6,7

METHODS

We performed a secondary data analysis of the US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to assess changes in self-reported insurance status, cost-related delays in care, and access to primary care (usual source of care and checkup in the last 12 months) before and after ACA coverage provisions began. The sample was restricted to nonelderly adults identifying as veterans (aged 18–64 years) in years 2011 to 2013 (pre-ACA) and 2015 to 2017 (post-ACA) in states that either expanded Medicaid under the ACA before 2015 or had not expanded as of 2017 (see explanation in the Appendix, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), which resulted in a total unweighted sample population of 142 449.

We measured coverage and access outcomes through preanalysis and postanalysis. We constructed linear probability models for each outcome measure by using a difference-in-differences approach to compare Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states in pre-ACA and post-ACA periods. We adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment, education, and national unemployment rate by year. We repeated analyses with 2 subgroups: low socioeconomic status (SES, defined as educational attainment of a high school diploma or less) and poor health status (defined by self-report of general health as “fair” or “poor”).

As a sensitivity analysis, we adjusted for state and year fixed effects, and we evaluated each primary outcome among all nonelderly veterans by US Census Bureau region. Finally, we repeated our analysis for veterans aged 67 years or older as a falsification test, because they were ineligible for coverage through the ACA. All analyses used BRFSS survey weights and were completed with Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics were similar among nonelderly veterans in the pre-ACA and post-ACA periods (Appendix Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Reports of delay in care because of cost declined 2.1 percentage points (11.9% to 9.8%; P < .01) among all nonelderly veterans, 3.4 percentage points (14.7% to 11.3%; P < .01) among low SES veterans, and 4.2 percentage points (25.6% to 21.4%; P < .01) among veterans in poor health. Reports of no usual source of care increased among all nonelderly veterans by 1.0 percentage point (24.1% to 25.1%; P < .01), and reports of no checkup in 12 months decreased 1.4 percentage points (28.0% to 26.6%; P < .01); changes among low SES and poor health subgroups were inconsistent in sign, statistical significance, or both (Appendix Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

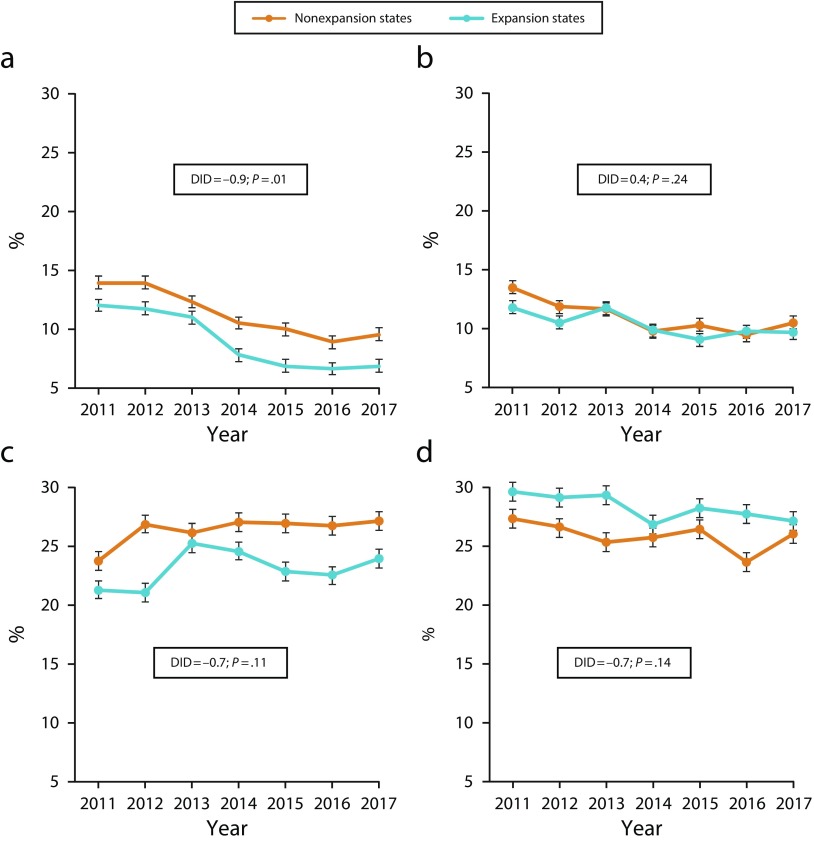

When comparing Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states, insurance coverage significantly improved in both expansion states and nonexpansion states, with a significantly larger gain of about 1 percentage point in expansion states (Figure 1). However, no significant differences were noted across the 2 types of states in cost-related delays in receiving care. Primary care measures—usual source of care and checkup within 12 months—improved significantly more in expansion than in nonexpansion states; however, changes were mixed among low SES and poor health subgroups.

FIGURE 1—

Unadjusted Changes in Nonelderly Veteran Insurance Coverage and Access to Care by State Medicaid Expansion Status for (a) No Insurance, (b) Delay in Receiving Care Due to Cost, (c) No Usual Source of Care, and (d) No Checkup in Last 12 Months: United States, 2011–2017

Note. Line graphs represent unadjusted marginal change in each specified outcome measure by year for all nonelderly veterans. Unadjusted difference-in-differences (DID) estimation is displayed as an overall percentage change in the specified outcome comparing the post–Affordable Care Act (ACA) period (2015–2017) with the pre-ACA period (2011–2013) in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states. Results of DID analyses were converted to percentages by multiplying regression coefficients by 100. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for point estimates. All values incorporate Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey weights.

Results of the state and year fixed-effects analyses did not significantly vary from the adjusted model (Appendix Tables C–F, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). When Medicaid expansion was examined by region, increases in coverage were larger in the South but did not correlate with improvements in access (Appendix Tables G–J, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Among veterans aged 67 years or older, changes in insurance status and cost-related delays were similar in pre-ACA and post-ACA periods. Small but statistically significant changes in primary care access measures were noted, similar to results for nonelderly veterans.

DISCUSSION

We observed that after 2014, cost-related delays in receiving care were reduced among nonelderly veterans, with larger reductions among low SES and poor health subgroups. Focusing specifically on the effect of Medicaid expansion, veterans in expansion states saw greater improvements in access than did those in nonexpansion states, although effects on low SES and fair or poor health veterans were not consistently significant. These results indicate that, overall, veterans’ access to care improved as a result of gains in coverage because of the ACA.

Addressing barriers to veterans’ health care access nevertheless remains a policy priority in the US health care system.8 Although challenges within the VHA have been widely publicized, ensuring veterans’ access to care in non-VHA settings has received considerably less attention. We found that for nonelderly veterans, gains in insurance coverage did not translate into uniform improvements in health care access. Specifically, unique barriers may exist in accessing primary care—even in regions where coverage gains were greatest.

One possible explanation for these barriers is that additional factors may influence veterans’ ability to seek health care, even when covered by insurance. Trust in medical providers9 and social determinants of health, including transportation, isolation,10 and health literacy, may affect veterans’ access to care disproportionately. Veterans’ ability to leverage social capital, navigate enrollment processes, or identify health care needs may be more limited. Veterans also may face geographic barriers to accessing care in both VHA and non-VHA settings. Compared with the general population, veterans more commonly live in rural areas, which may affect access to care.11

This study had potential limitations. Responses in BRFSS are self-reported, which is subject to recall bias and social desirability bias. Our study examined changes for only 3 years following the adoption of ACA coverage provisions, and trends may change over time. Parallel trends in difference-in-differences analyses did not hold for some outcomes, such as cost-related delays or no usual source of care, which may have resulted in biased estimates. In addition, this study did not examine actual use of primary care or other health care services through administrative data. We instead relied on veterans’ self-report of visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Access to high-quality health care for veterans is a policy priority in the United States. In a 3-year period following enactment of ACA coverage provisions, cost-related delays in care were reduced, with greater reductions among veterans with low SES and poor health. However, results for measures of access to primary care were mixed. These findings suggest that ACA coverage provisions may have reduced financial barriers to accessing health care; however, additional study is needed to understand veterans’ unique challenges in accessing primary care services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A. T. Kelley is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Michigan. R. Tipirneni is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 career development award AG056591).

This article was presented at the Society for General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on May 8, 2019, and at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting on June 3, 2019.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No institutional review board approval was necessary because this study used publicly available de-identified national data sets.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chokshi DA, Sommers BD. Universal health coverage for US veterans: a goal within reach. Lancet. 2015;385(9984):2320–2321. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61254-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Uninsured veterans who will need to obtain insurance coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e57–e62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haley JM, Gates J, Buettgens M, Kenney GM. Veterans and their family members gain coverage under the ACA, but opportunities for more progress remain. Urban Institute; September 27, 2016. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/veterans-and-their-family-members-gain-coverage-under-aca-opportunities-more-progress-remain. Accessed July 4, 2018.

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation. Key facts about the uninsured population. December 7, 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/fact-sheet/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population. Accessed November 8, 2018.

- 5.Haley JM, Kenney GM, Gates J. Veterans saw broad coverage gains between 2013 and 2015. Urban Institute; April 19, 2017. Available at: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/veterans-saw-broad-coverage-gains-between-2013-and-2015. Accessed June 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller S, Wherry LR. Health and access to care during the first 2 years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):947–956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1612890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Antonisse L, Garfield R, Rudowitz R, Artiga S. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: updated findings from a literature review. Kaiser Family Foundation; March 28, 2018. Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-effects-of-medicaid-expansion-under-the-aca-updated-findings-from-a-literature-review-march-2018. Accessed October 5, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daley J. Ensuring timely access to quality care for US veterans. JAMA. 2018;319(5):439–440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Redihan S, Borgia M, Rose J. Needing primary care but not getting it: the role of trust, stigma and organizational obstacles reported by homeless veterans. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):1019–1031. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fried DA, Passannante M, Helmer D, Holland BK, Halperin WE. The health and social isolation of American veterans denied Veterans Affairs disability compensation. Health Soc Work. 2017;42(1):7–14. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlw051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohl ME, Carrell M, Thurman A et al. Availability of healthcare providers for rural veterans eligible for purchased care under the Veterans Choice Act. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):315. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3108-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]