Abstract

Objectives. To document ethnic disparities in childhood abuse and neglect among New Zealand children.

Methods. We followed the 1998 New Zealand birth cohort of 56 904 children through 2016. We determined the cumulative childhood prevalence of reports to child protective services (CPS), substantiated maltreatment (by subtype), and out-of-home placements, from birth to age 18 years, by ethnic group. We also developed estimates stratified by maternal age and community deprivation levels.

Results. We identified substantial ethnic differences in child maltreatment and child protection involvement. Both Māori and Pacific Islander children had a far greater likelihood of being reported to CPS, being substantiated as victims, and experiencing an out-of-home placement than other children. Across all levels of CPS interactions, rates of Māori involvement were more than twice those of Pacific Islander children and more than 3 times those of European children.

Conclusions. Despite long-standing child support policies and reparation for breaches of Indigenous people’s rights, significant child maltreatment disparities persist. More work is needed to understand how New Zealand’s public benefit services can be more responsive to the needs of Indigenous families and their children.

Longitudinal and population-based studies based on child protective services (CPS) records have established at least 3 important epidemiological realities consistent across countries and cultural contexts. First, the cumulative prevalence of childhood maltreatment and CPS involvement is much greater than what was previously appreciated.1–6 Second, the burden of maltreatment falls disproportionately on children from already disadvantaged groups.7,8 Third, persistent inequities in socioeconomic opportunities mean that race and ethnicity amount to de facto markers for both disadvantage and risk of childhood abuse and neglect.9,10

Published findings from New Zealand indicate that 23.5% of children (≤ 17 years) are reported for maltreatment, 9.7% are substantiated as victims of abuse or neglect, and 3.1% experience an out-of-home placement.3 It has been noted that examining ethnic differences in these rates is an important area for further study.6 Subgroup estimates are especially relevant given that Māori and Pacific Islander children compose almost one third of births in New Zealand and experience heightened rates of poverty and other adversities.7,10,11 In this brief, we assess disparities in the cumulative prevalence of maltreatment and CPS involvement among ethnic groups for a New Zealand birth cohort.

METHODS

Using data from New Zealand’s Integrated Data Infrastructure, we identified the full population of children whose births were registered in 1998. We coded each birth by maternal ethnicity and age at birth. We assigned each child to a single ethnic group using established New Zealand data protocols and used maternal age to classify births to adolescent (13–19 years) and nonadolescent (≥ 20 years) mothers. We excluded births in which maternal ethnicity was missing on the birth record (0.8%), as well as those where Integrated Data Infrastructure records indicated the child had migrated out of New Zealand (2.8%). Children who migrated out of New Zealand tended to have a different demographic profile (i.e., more likely to be children of migrants, less likely to be born to parents with a criminal record). Our final birth cohort consisted of 56 904 births, with 59% classified as of European origin, 23.1% as Māori, 10.1% as Pacific Islander, 6.7% as Asian, and 1.1% as other ethnicity. Overall, 13.2% of Māori and 6% of Pacific Islander children were born to adolescent mothers, compared with 1.3% of Asian and 3.2% of European children. Maternal birth date was missing for 0.3% of our birth cohort.

We documented CPS involvement using maltreatment records in the Integrated Data Infrastructure, extracting information on interactions occurring between 1998 and 2016, including (1) reports of alleged maltreatment, (2) substantiated maltreatment findings, and (3) out-of-home placements. Reports reflect notifications made to CPS from professionals and members of the community. Substantiated findings are investigated reports with evidence validating that maltreatment occurred. We present cumulative childhood substantiated findings overall and by maltreatment subtype (i.e., neglect; emotional, physical, or sexual abuse). Subtype rates do not sum to the overall total because a child could have been substantiated for different forms of maltreatment. Out-of-home placements with kin, with foster parents, or in a residential facility arise when a court removes a child involuntarily or places a child with the parents’ consent.

We used the first event date to code the cumulative prevalence of children experiencing each level of CPS interaction between birth and age 18 years, by ethnicity. We additionally conducted a sensitivity analysis of ethnic disparities by neighborhood characteristics. We used New Zealand’s Index of Multiple Deprivation and assigned each child a census meshblock code based on his or her residential address at birth. Because the index is only computed with every 5-year census, we relied upon data for 2001 for estimates closest to the child’s birth. For 5.4% of births, we were unable to locate a meshblock for 2001, but identified a code based on the 2006 census. Overall, we managed to assign 98.4% of children in the birth cohort to a meshblock. For each ethnicity, we then reestimated the cumulative rates of CPS interactions, stratified by community deprivation.

For all analyses, we used Stata MP, version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). We applied Statistics New Zealand confidentiality rules, which include the random rounding of all counts to base 3 and the suppression of output if the underlying unrounded count was fewer than 6.

RESULTS

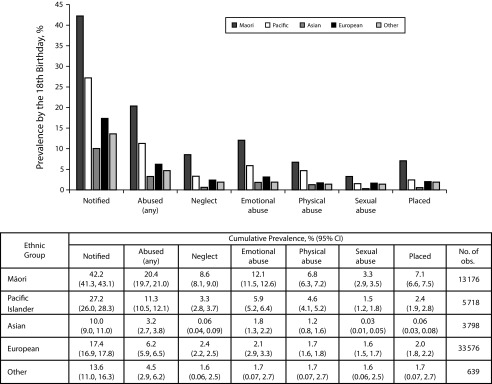

We present childhood prevalence of CPS involvement by ethnicity in Figure 1. Across all levels of CPS involvement—reports, substantiations, and placements—Māori children had the highest rates (42.2%, 20.4%, and 7.1%, respectively) and Asian children the lowest rates (10.0%, 3.2%, and 0.6%, respectively). Pacific Islander children had childhood rates of maltreatment and CPS interactions that were elevated relative to other ethnic groups, but still appreciably lower than Māori rates. We observed higher rates of maltreatment in each abuse-type category for Māori children, with the prevalence of physical abuse almost 5 times that of European children (6.7% vs 1.7%). Ethnic disparities were reduced among children born to adolescent mothers (Figure A and Table A, available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), but they persisted across all levels of CPS interactions even after we stratified by aggregate neighborhood deprivation (Figure B available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

Cumulative Prevalence of CPS Notifications, Substantiations, and Placements for Children Born in 1998 in New Zealand, by Ethnic Group

Note. CI = confidence interval; CPS = child protective services; obs. = observations. CPS involvement is measured from birth up to 18th birthday. We applied Statistics New Zealand confidentiality rules to counts, which included the random rounding of all counts to base 3.

Source. Statistics New Zealand’s Integrated Data Infrastructure.

DISCUSSION

The high prevalence of substantiated maltreatment and CPS interactions among Indigenous Māori and Pacific Islander children is striking. Documented disparities emerge in our data within complex historical and contemporary contexts that characterize New Zealand. Although Pacific peoples have a long history of immigration and settlement in New Zealand, they also face high levels of social disadvantage through the restructuration of industries they were initially recruited for. Māori, in particular, face ongoing effects of colonization, assimilation, and contemporary social, economic, and educational disadvantage.10,11

Disparities also emerge in the context of a policy environment within the country. During the period of study, New Zealand provided cash benefits to single parents, supported universal home-visiting programs, and funded a national public health system. Although these are all important foundations of maltreatment prevention and addressing social inequities, Māori are known to underutilize primary health care services, are more likely to have unmet health needs, and experience other institutionalized barriers to accessing health and welfare systems.11,12

Notwithstanding the methodological strength of a population-based, prospective birth cohort study, findings must be interpreted within the proper framework. We do not attempt to make any child-level adjustments for poverty or other factors tied to maltreatment risk or CPS involvement. Although ethnic disparities continue to emerge across our aggregated summary measure of neighborhood deprivation, disparities are modified when we stratify by a simple sociodemographic measure of maternal age. Additionally, we are unable to resolve whether observed disparities reflect increased surveillance or differential standards for reports, substantiations, and placements across ethnic groups.10 That said, self-report data confirm a higher prevalence of maltreatment among Māori.7 Documenting the magnitude of ethnic disparities in these service interactions is a critical step to informed discussions of root causes.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

We do not know what the relative prevalence of maltreatment and CPS involvement for Māori and Pacific Islander children would have been absent existing New Zealand welfare policies. Our study, however, suggests that the available safety net and associated policies have failed to remediate conditions tied to maltreatment risk. Given the near and long-term consequences of childhood abuse and neglect, reducing ethnic disparities is critical to producing greater equity in outcomes throughout the life course. A better understanding of effective strategies for engaging Indigenous communities is needed.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was needed for this study because only de-identified data were used.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bilson A, Cant RL, Harries M, Thorpe DH. A longitudinal study of children reported to the Child Protection Department in Western Australia. Br J Soc Work. 2015;45(3):771–791. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim H, Wildeman C, Jonson-Reid M, Drake B. Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(2):274–280. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouland B, Vaithianathan R. Cumulative prevalence of maltreatment among New Zealand children, 1998–2015. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):511–513. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ubbesen M, Gilbert R, Thoburn J. Cumulative incidence of entry into out-of-home care: changes over time in Denmark and England. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;42:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wildeman C. The incredibly credible prevalence of child protective services contact in New Zealand and the United States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):438–439. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marie D, Fergusson D, Boden J. Ethnic identity and exposure to maltreatment in childhood: evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. Soc Policy J N Z. 2009;36:154–171. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B, King B, Johnson-Motoyama M. Racial and ethnic disparities: a population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth RP, Jonson-Reid M. Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):471–478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cram F, Gulliver P, Ota R, Wilson M. Understanding overrepresentation of indigenous children in child welfare data: an application of the Drake risk and bias models. Child Maltreat. 2015;20(3):170–182. doi: 10.1177/1077559515580392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morton SMB, Atatoa Carr PE, Grant CC et al. Cohort profile: growing up in New Zealand. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(1):65–75. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, Waldegrave K, Karlsen S, Nazroo J. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in new Zealand: cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2006;367(9527):2005–2009. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68890-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]