Abstract

Objectives. To characterize prescription opioid medical users and misusers among US adults.

Methods. We used the 2016–2017 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health to compare medical prescription opioid users with misusers without prescriptions, misusers of own prescriptions, and misusers with both types of misuse. Multinomial logistic regressions identified substance use characteristics and mental and physical health characteristics that distinguished the groups.

Results. Among prescription opioid users, 12% were misusers; 58% of misusers misused their own prescriptions. Misusers had higher rates of substance use than did medical users. Compared with with-prescription-only misusers, without-and-with-prescription misusers and without-prescription-only misusers had higher rates of marijuana use and benzodiazepine misuse; without-and-with-prescription misusers had higher rates of heroin use. Compared with without-prescription-only misusers, without-and-with-prescription and with-prescription-only misusers had higher rates of prescription opioid use disorder. Most misusers, especially with-prescription-only misusers, used prescription opioids to relieve pain. Misusers were more likely to be depressed than medical users.

Conclusions. Prescription opioid misusers who misused both their own prescriptions and prescription opioid drugs not prescribed to them may be most at risk for overdose. Prescription opioid misuse is a polysubstance use problem.

Despite declines in prescribing1,2 and nonmedical use,3,4 prescription opioid (PO) deaths increased from 3442 deaths in 1999 to 17 029 in 2017.5,6 These deaths represent 35.8% of all opioid overdose deaths, including synthetic opioids (illicit fentanyl) and heroin.5 The longitudinal population data necessary to understand which PO users are most at risk for negative outcomes are unavailable. Official health and death records do not indicate whether opioids were used as prescribed by a physician or misused, but only whether POs or other drugs contributed to overdoses or deaths. We calculated that, in 2014 and 2015, 5 substances other than POs (alcohol, cocaine, heroin, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants) were involved in 60% of natural and semisynthetic opioid deaths7; in 2017, the proportion was similar (61.4%). Identifying the characteristics of PO misusers compared with those who use opioids only as prescribed (medical use) is crucial for understanding who is most at risk for adverse outcomes from POs and for targeting prevention and treatment efforts.

Until 2015, national epidemiological data were restricted to PO misuse. No nationally representative data were available on prescribed PO use to permit comparisons of misusers and medical users. The only available information was from individuals in drug treatment and primary care clinics.8,9 Misusers were more likely than were medical users to use and be dependent on licit and illicit drugs.9 Medical users reported higher pain levels and more medical visits.9 Findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the annual assessment of drug use in the US population, indicate that PO misusers who obtained prescription opioids from a physician report more frequent PO use and poorer health but less illicit drug use and deviance than do those who obtained prescription opioids from a nonmedical source.10,11

As of 2015, the NSDUH continued to assess PO misuse but introduced questions that made it possible to infer medical use.12 One report compared medical users with PO misusers with and without a PO use disorder in 2015,13 and another compared 5 levels of opioid exposure, from no opioid use to heroin use in 2015 and 2016.14 Misusers, especially those with a PO use disorder, had higher rates of substance use, mental health problems, criminal records, and lower economic resources than did medical users.13,14

Using data from the 2016–2017 NSDUH surveys, we examined PO medical users and misusers, and we refined the definition of misuse to consider PO sources: whether one’s own prescription or from a nonmedical source. Misusers were differentiated according to whether they misused their own prescribed opioids exclusively, misused POs without a prescription from a nonmedical source exclusively, or misused both ways. We characterized medical users and the 3 misuser groups by substance use and disorder, mental and physical health, and sociodemographic characteristics, and implemented multivariate analyses to identify unique correlates of each group. We also examined gender differences.15,16 The results have implications for prevention and treatment, because misusers of their own prescriptions could be identified by physicians, even when patients misuse from nonmedical sources. The findings based on survey data provide insight into which PO users may contribute to overdoses.

METHODS

The sample included past-12-month PO users aged 18 years and older (n = 29 241) from the 2016–2017 NSDUH, an annual survey of a multistage representative area probability sample of the noninstitutionalized US population aged 12 years and older. The target population represents 98% of the population. Persons in noninstitutional group quarters and civilians on military bases are included; individuals on active military duty, in jail, in drug treatment programs, and in hospitals are excluded. Age groups at highest risk for drug use (12–17 and 18–25 years) are oversampled. Data about substance use are collected via computer-assisted personal interviews. Completion rates were 53.3% in 2016 and 50.3% in 2017.17,18

Measures

Identification of past-12-month prescription opioid misusers and medical users.

We combined 3 variables—PO use or misuse, type of misuse, and source of last PO misuse—to define medical PO users and 3 misuser groups. (1) One question asked separately about use or misuse of 37 PO pain relievers in the past 12 months. Misuse was use in any way not directed by a doctor (a) without own prescription; (b) in greater amounts, more often, or longer than prescribed; or (c) any other way. (2) A multiple-choice question inquired about overall type of misuse in past 12 months, per definitions a through c. (3) We ascertained source of last PO misuse as own prescription from 1 or more than 1 doctor, or without prescription from a nonmedical source: obtained, bought, or taken from friend or relative; stolen from doctor’s office, hospital, or pharmacy; bought from drug dealer or stranger; got some other way. We defined 3 groups: (1) misused without a prescription exclusively (without-prescription-only misusers; n = 1885); (2) misused own prescription exclusively (with-prescription-only misusers; n = 1048); (3) misused both without a prescription and with one’s own prescription (without-and-with-prescription misusers; n = 1470). We did not classify medical users (n = 24 661) as misusers; we excluded 177 misusers because of missing data.

Prescription opioid drug subtypes.

The NSDUH categorized the 37 PO drugs into 11 subtypes: hydrocodone, oxycodone, tramadol, buprenorphine, morphine, oxymorphone, fentanyl, Demerol, hydromorphone, methadone, and other.

Other variables.

The NSDUH assessed PO use disorder in past the 12 months only among misusers, per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) criteria for dependence (≥ 3 of 7) or abuse (≥ 1 of 4).19 Misusers selected the reasons for their last misuse as follows: to relieve physical pain; to relax or relieve tension; to experiment; to feel good or get high; to help with sleep; to help with feelings or emotions; to increase or decrease effect(s) of some other drug; because hooked; other reason. Each coded 0 = no or 1 = yes.

Substance use measures included assessments of nicotine use and dependence in past 30 days, measured per the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale,20 and past-12-month alcohol and marijuana use and disorder, defined per DSM-IV criteria for dependence or abuse.19 For each drug, we created a 3-category variable (0 = no use; 1 = used, no dependence or disorder; 2 = dependence or disorder. We coded past-12-month use of cocaine and heroin as 0 = no or 1 = yes. We coded past-12-month use or misuse of benzodiazepines (tranquilizers or sedatives) and stimulants as 0 = no use, 1 = medical use (use not classified as misuse), or 2 = misuse. We coded respondents’ reports of past-12-month alcohol or drug treatment as 0 = no or 1 = yes. We created an index from 11 questions averaging respondents’ perceptions about the risk of harming themselves from using 6 drugs (coded 1 = no risk, 2 = slight, 3 = moderate, 4 = great risk for each): “smoking 1 or more packs of cigarettes per day”; “having 5 or more alcohol drinks once or twice a week” and “4 or 5 drinks nearly every day”; using marijuana and cocaine each “once a month” or “once or twice a week”; using LSD and heroin each “once or twice” or “once or twice a week.”

Delinquency in the past 12 months combined 2 items: number of times “stole or tried to steal anything worth more than $50.00” and “attacked someone with the intent to hurt them,” coded 0 = none or 1 = any. Major depressive episode in the past 12 months (0 = no, 1 = yes) was defined by the NSDUH as having at least 5 of 9 depression symptoms nearly every day in a 2-week period, per DSM-IV criteria.19 We coded inpatient mental health treatment and prescribed medication use for a mental health condition in the past 12 months as 0 = no or 1 = yes.

Physical health indicators included self-reports of any of the following 10 diagnosed health conditions in their lifetime: heart problems, high blood pressure, diabetes, chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis B or C, kidney disease, asthma, HIV/AIDS, or cancer (coded 0 = none or 1 = any). We recoded respondents’ ratings of their overall health as 0 = excellent, very good, or good or 1 = fair or poor. We coded reports of the number of emergency room visits in the past 12 months as 0 = none or 1 = any (range = 0 to ≥ 31). We coded having health insurance as 0 = no or 1 = yes.

Sociodemographic characteristics included age (18–34, 35–49, ≥ 50 years); gender (male, female); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American, Hispanic, other); educational level (high school or less, some college or more); family income (< $20 000, $20 000–$49 999, $50 000–$74 999, ≥ $75 000); marital status (married, not married); and residential county (large metropolitan, small metropolitan, nonmetropolitan) based on the 2013 Rural–Urban Continuum Codes developed by the US Department of Agriculture and applied by the NSDUH.17 NSDUH interview questions and constructed variables are available elsewhere.17,18,21

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive proportions of all respondents’ characteristics stratified by the 4 types of PO use and misuse. Two multivariable multinomial logistic regressions tested differences among PO user groups, controlling for all characteristics. One model tested the odds of being from each of the 3 misuser groups compared with medical users for each characteristic. A second model, restricted to misusers, tested 3 comparisons: with-prescription-only misusers versus without-prescription-only misusers, without-and-with-prescription misusers versus without-prescription-only misusers, and without-and-with-prescription misusers versus with-prescription-only misusers. This model also included PO disorder and reasons for last PO misuse ascertained only among misusers. We estimated gender-specific multinomial logistic regressions. We estimated gender-by-factor interactions in the total sample to test for gender differences.

We implemented analyses in SUDAAN 11.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute International, Research Triangle Park, NC), adjusting for design effects by Taylor series linearization and sample weights reflecting selection probabilities at various stages of the sampling design.

RESULTS

In 2016 and 2017, of noninstitutionalized adults aged 18 years and older in the population, 31.0% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 30.5%, 31.5%; annual weighted n = 76.2 million) used POs only medically as prescribed by a physician, and 4.2% (95% CI = 4.1%, 4.4%; annual weighted n = 10.4 million) misused them. The overwhelming majority of all PO users (88.0%; 95% CI = 87.5%, 88.5%) used only medically; 12.0% (95% CI = 11.5%, 12.5%) misused. Among misusers, 38.2% (95% CI = 35.9%, 40.7%; annual weighted n = 4.0 million) misused exclusively without a prescription from a nonmedical source (without-prescription-only); 27.1% (95% CI = 25.1%, 29.3%; annual weighted n = 2.8 million) misused exclusively their own prescription (with-prescription-only); 30.9% (95% CI = 28.8%, 33.0%; annual weighted n = 3.2 million) misused both ways (without-and-with-prescription); 3.8% (95% CI = 3.0%, 4.7%; annual weighted n = 0.4 million) could not be classified. Thus, 58.0% (95% CI = 55.7%, 60.3%) of PO misusers misused their own prescribed opioids.

Most without-prescription-only misusers (87.7%; 95% CI = 85.5%, 89.6%) obtained their last PO from a friend or relative. Almost all with-prescription-only misusers (97.5%; 95% CI = 96.1%, 98.4%) obtained their last PO from 1 doctor (Table 1). Of without-and-with-prescription misusers, only 24.7% (95% CI = 21.4%, 28.4%) did so; 57.0% (95% CI = 53.3%, 60.5%) obtained their last PO from a friend or relative and 10.4% (95% CI = 8.4%, 12.8%) obtained it from a drug dealer or stranger.

TABLE 1—

Source of Last Prescription Opioid Misuse Among 3 Groups of Past-12-Month Prescription Opioid Misusers (Aged ≥ 18 Years): United States, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2016–2017

| Source of Last Misuse | Without-Prescription-Only Misusers (n = 1885), % (95% CI) |

Without-and-With-Prescription Misusers (n = 1470), % (95% CI) |

With-Prescription-Only Misusers (n = 1048), % (95% CI) |

Shah’s Wald F-Test (n = 4403) (df)a |

| 1 doctor | . . . | 24.7 (21.4, 28.4) | 97.5 (96.1, 98.4) | (10, 50) = 109.4*** |

| > 1 doctor | . . . | 1.5 (0.6, 3.5) | 2.5 (1.6, 3.9) | . . . |

| Stole from doctor’s office, clinic, hospital, pharmacy | 0.5 (0.2, 1.4) | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | . . . | . . . |

| Friend or relative | 87.7 (85.5, 89.6) | 57.0 (53.3, 60.5) | . . . | . . . |

| Drug dealer or stranger | 6.3 (5.1, 7.8) | 10.4 (8.4, 12.8) | . . . | . . . |

| Other | 5.5 (4.5, 6.8) | 5.2 (3.7, 7.3) | . . . | . . . |

Note. CI = confidence interval. The sample size was n = 4403. Estimates are weighted; sample sizes are unweighted.

Shah’s Wald F-test for percentage differences in source of last misuse by misuser groups.

P < .001.

Descriptive Analysis

Higher proportions of without-and-with-prescription misusers (43.3%; 95% CI = 39.3%, 47.4%) used 3 or more PO subtype drugs than with-prescription-only misusers (30.0%; 95% CI = 25.8%, 34.5%), without-prescription-only misusers (26.6%, 95% CI = 24.0%, 29.5%), and, especially, medical users (12.4%; 95% CI = 11.8%, 13.1%; Table 2). A larger proportion of without-and-with-prescription misusers misused most PO subtypes than did other misusers. The 3 most frequently misused PO drugs were hydrocodone, oxycodone, and tramadol. Fentanyl was used medically more by misusers of their own POs, irrespective of whether they also misused without a prescription. Fentanyl and buprenorphine were misused most by without-and-with-prescription misusers, as were morphine, oxymorphone, hydromorphone, and methadone.

TABLE 2—

Past-12-Month Medical Use and Misuse of Subtypes of Prescription Opioid Drugs Among 3 Groups of Misusers and Medical Users (Aged ≥ 18 Years): United States, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2016–2017

| Without-Prescription-Only Misusers (n = 1885), % (95% CI) |

Without-and-With-Prescription Misusers (n = 1470), % (95% CI) |

With-Prescription-Only Misusers (n = 1048), % (95% CI) |

Medical Users (n = 24 661), % (95% CI) |

Shah’s Wald F-Test (df)a | |

| No. of PO drug subtypes usedb | |||||

| 1 | 36.1 (32.7, 39.7) | 24.4 (20.8, 28.5) | 32.7 (28.9, 36.8) | 54.1 (53.0, 55.1) | (9, 50) = 43.6*** |

| 2 | 30.1 (27.1, 33.2) | 26.2 (22.7, 30.1) | 31.4 (27.4, 35.7) | 24.3 (23.5, 25.0) | |

| ≥3 | 26.6 (24.0, 29.5) | 43.3 (39.3, 47.4) | 30.0 (25.8, 34.5) | 12.4 (11.8, 13.1) | |

| PO drug subtypesc | |||||

| Hydrocodone | |||||

| Medical only | 11.1 (9.4, 13.1) | 12.4 (10.0, 15.4) | 16.7 (13.8, 20.0) | 58.2 (57.2, 59.2) | (6, 50) = 267.4*** |

| Misuse | 60.2 (57.3, 63.1) | 64.3 (60.6, 67.8) | 61.2 (57.3, 65.1) | . . . | |

| Oxycodone | |||||

| Medical only | 10.4 (8.4, 12.8) | 14.7 (12.0, 17.9) | 19.4 (16.7, 22.4) | 27.4 (26.7, 28.2) | (6, 50) = 195.1*** |

| Misuse | 37.0 (33.6, 40.7) | 42.0 (38.0, 46.2) | 26.2 (22.5, 30.2) | . . . | |

| Tramadol | |||||

| Medical only | 11.1 (9.4, 13.1) | 15.5 (13.2, 18.1) | 12.0 (9.3, 15.2) | 20.3 (19.6, 21.0) | (6, 50) = 66.9*** |

| Misuse | 16.3 (14.0, 18.9) | 16.5 (14.3, 19.0) | 13.7 (10.7, 17.3) | . . . | |

| Buprenorphine | |||||

| Medical only | 2.5 (1.8, 3.5) | 7.8 (5.7, 10.6) | 3.2 (1.8, 5.6) | 1.4 (1.2, 1.7) | (6, 50) = 41.8*** |

| Misuse | 6.2 (5.0, 7.7) | 12.2 (9.6, 15.5) | 2.5 (1.6, 4.0) | . . . | |

| Morphine | |||||

| Medical only | 3.6 (2.3, 5.5) | 7.9 (6.0, 10.2) | 7.7 (5.7, 10.2) | 6.3 (5.9, 6.8) | (6, 50) = 37.0*** |

| Misuse | 3.8 (3.0, 4.8) | 7.7 (6.0, 9.9) | 2.9 (1.8, 4.7) | . . . | |

| Oxymorphone | |||||

| Medical only | 1.0 (0.5, 1.7) | 3.3 (2.1, 5.2) | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | (6, 50) = 24.2*** |

| Misuse | 2.2 (1.6, 3.3) | 5.7 (4.1, 7.8) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.1) | . . . | |

| Fentanyl | |||||

| Medical only | 0.9 (0.4, 1.8) | 4.3 (2.9, 6.2) | 3.7 (2.3, 6.0) | 1.8 (1.5, 2.1) | (6, 50) = 12.5*** |

| Misuse | 2.2 (1.4, 3.3) | 3.9 (2.7, 5.7) | 0.9 (0.4, 2.1) | . . . | |

| Demerol | |||||

| Medical only | 1.4 (0.7, 2.6) | 3.3 (2.2, 5.1) | 2.7 (1.8, 4.0) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) | (6, 50) = 7.9*** |

| Misuse | 0.7 (0.3, 1.8) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.6) | 1.1 (0.3, 3.3) | . . . | |

| Hydromorphone | |||||

| Medical only | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.9) | 2.9 (1.9, 4.4) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.2) | (6, 50) = 14.7*** |

| Misuse | 1.7 (1.0, 2.8) | 4.6 (3.3, 6.4) | 1.2 (0.5, 2.8) | . . . | |

| Methadone | |||||

| Medical only | 1.9 (1.2, 3.0) | 4.7 (3.6, 6.2) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.6) | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | (6, 50) = 16.1*** |

| Misuse | 1.8 (1.2, 2.8) | 4.7 (3.2, 6.8) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.9) | . . . | |

| Other | |||||

| Medical only | 13.2 (11.0, 15.7) | 18.0 (15.1, 21.3) | 16.2 (12.9, 20.3) | 25.1 (24.3, 26.0) | (6, 50) = 62.5*** |

| Misuse | 5.7 (4.1, 7.7) | 7.4 (5.9, 9.3) | 7.6 (5.6, 10.3) | . . . | |

Note. CI = confidence interval; PO = prescription opioid. The sample size was n = 29 064. Estimates are weighted; sample sizes are unweighted.

Shah’s Wald F-tests for percentage differences in subtypes of prescription opioid drugs used across misuser groups and medical users.

Missing category not shown.

Hydrocodone products include Vicodin, Lortab, Norco, Zohydro ER, and hydrocodone (generic). Oxycodone products include OxyContin, Percocet, Percodan, Roxicet, Roxicodone, and oxycodone (generic). Tramadol products include Ultram, Ultram ER, Ultracet, tramadol (generic), and extended-release tramadol (generic). Buprenorphine products include Suboxone and buprenorphine (generic). Morphine products include Avinza, Kadian, MS Contin, morphine (generic), and extended-release morphine (generic). Oxymorphone products include Opana, Opana ER, oxymorphone (generic), and extended-release oxymorphone (generic). Fentanyl products include Actiq, Duragesic, Fentora, and fentanyl (generic). Hydromorphone products include Dilaudid or hydromorphone (generic), and Exalgo or extended-release hydromorphone (generic).12

P < .001.

Relieving pain was the most commonly reported reason for PO use by misusers, especially by with-prescription-only misusers (81.5%; 95% CI = 77.7%, 84.8%), compared with without-prescription-only misusers (70.0%; 95% CI = 67.6%, 72.3%) and without-and-with-prescription misusers (64.9%; 95% CI = 60.5%, 69.0%; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Compared with other groups, without-and-with-prescription misusers mentioned more reasons for their last PO misuse, particularly to relax, to feel good or get high, or to help with feelings or emotions.

PO misusers differed from each other and from medical users by sociodemographic characteristics and by mental and physical health (Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Without-prescription-only misusers were younger than other groups. Without-prescription-only and without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to be male and less likely to be married than were with-prescription-only misusers and medical users. Without-and-with-prescription misusers had lower education than other groups. With-prescription-only misusers were more likely to live in a large metropolitan area.

Multivariate Analysis

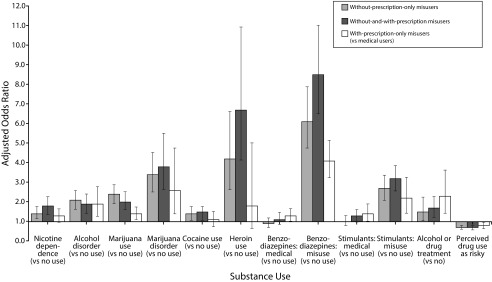

Compared with medical users, controlling for all characteristics, all misusers were more likely to have an alcohol disorder, to use marijuana or have a marijuana disorder, and to misuse benzodiazepines and stimulants (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.4–8.5; Figure 1 and Table C, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org); all misusers were more likely to have been treated for alcohol or substance use (AOR = 1.5–2.3) and to perceive drug use as less risky (AOR = 0.7–0.8). Without-prescription-only and without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to be nicotine dependent and to use cocaine and heroin (AOR = 1.4–6.7). With-prescription-only misusers were more likely to use benzodiazepines and stimulants medically (AOR = 1.3–1.4).

FIGURE 1—

Comparison of Substance Use Between 3 Groups of Past-12-Month Prescription Opioid Misusers and Medical Users (Aged ≥ 18 Years): United States, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2016–2017

Note. The sample size was n = 29 064.

Compared with medical users, all misusers were more likely to be depressed (AOR = 1.4–1.5; online Table C); without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to have received inpatient mental health treatment and to take medication for a mental health condition (AOR = 1.3–1.5), but less likely to have a physical health condition (AOR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.66, 0.98). Without-prescription-only and without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to engage in delinquent behavior (AOR = 1.7–2.0) and less likely to visit an emergency room (AOR = 0.6–0.7) than were medical users; with-prescription-only misusers were more educated (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.08, 1.66) and less likely to live in a nonmetropolitan area (AOR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.43, 0.70).

We estimated a model restricted to the 3 misuser groups, which included PO use disorder and reasons for last PO misuse (Table 3). Without-and-with-prescription and with-prescription-only misusers were more likely to have a PO use disorder than were without-prescription-only misusers (AOR = 2.0–2.4). Without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to misuse POs to feel good or get high than were the 2 other misusers groups (AOR = 1.5–1.8), whereas with-prescription-only misusers were more likely to misuse POs to relieve pain than were without-prescription-only misusers (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.00, 1.74). Without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to use marijuana (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI = 1.00, 1.78) and heroin (AOR = 3.5; 95% CI = 1.33, 9.22) and to misuse benzodiazepines (AOR = 2.1; 95% CI = 1.49, 2.82) than were with-prescription-only misusers. With-prescription-only misusers were less likely to use marijuana (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI = 0.49, 0.91) and to misuse benzodiazepines (AOR = 0.6; 95% CI = 0.45, 0.80) than were without-prescription-only misusers. The loss of significance regarding heroin use and benzodiazepine misuse between without-and-with-prescription and without-prescription-only misusers was accounted for by the inclusion of PO use disorder in the model.

TABLE 3—

Comparison of Substance Use, Prescription Opioid Use Disorder, and Reasons for Last Prescription Opioid Misuse Among Past-12-Month Prescription Opioid Misuser Groups (Aged ≥ 18 Years): United States, National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2016–2017

| Substance Usea | With-Prescription-Only vs Without-Prescription-Only Misusers, AOR (95% CI) | Without-and-With-Prescription vs Without-Prescription-Only Misusers, AOR (95% CI) | Without-and-With-Prescription vs With-Prescription-Only Misusers, AOR (95% CI) |

| Nicotine (vs no use) | |||

| Use only | 0.8 (0.59, 1.01) | 0.9 (0.69, 1.18) | 1.2 (0.90, 1.54) |

| Dependence | 0.9 (0.61, 1.21) | 1.1 (0.83, 1.47) | 1.3 (0.94, 1.76) |

| Alcohol (vs no use) | |||

| Use only | 0.9 (0.60, 1.25) | 0.8 (0.60, 1.12) | 0.9 (0.68, 1.31) |

| Disorder | 1.0 (0.65, 1.56) | 1.0 (0.69, 1.30) | 0.9 (0.66, 1.35) |

| Marijuana (vs no use) | |||

| Use only | 0.7 (0.49, 0.91) | 0.9 (0.65, 1.21) | 1.3 (1.00, 1.78) |

| Disorder | 0.7 (0.42, 1.14) | 1.0 (0.72, 1.50) | 1.5 (0.87, 2.62) |

| Cocaine use (vs no use) | 0.8 (0.50, 1.28) | 1.1 (0.80, 1.47) | 1.4 (0.89, 2.06) |

| Heroin use (vs no use) | 0.4 (0.16, 1.05) | 1.5 (0.94, 2.27) | 3.5 (1.33, 9.22) |

| Benzodiazepines (vs no use) | |||

| Medical use | 1.3 (0.86, 2.03) | 1.2 (0.81, 1.66) | 0.9 (0.59, 1.30) |

| Misuse | 0.6 (0.45, 0.80) | 1.2 (0.93, 1.65) | 2.1 (1.49, 2.82) |

| Simulants (vs no use) | |||

| Medical use | 1.4 (0.95, 2.14) | 1.2 (0.87, 1.56) | 0.8 (0.56, 1.20) |

| Misuse | 0.8 (0.52, 1.11) | 1.1 (0.81, 1.40) | 1.4 (0.95, 2.08) |

| Alcohol or drug treatment (vs none) | 1.2 (0.71, 2.04) | 0.9 (0.64, 1.30) | 0.8 (0.47, 1.23) |

| Perceived drug use as risky | 1.1 (0.87, 1.47) | 1.0 (0.76, 1.20) | 0.8 (0.67, 1.05) |

| Prescription opioid (PO) disorder (vs no disorder) | 2.4 (1.77, 3.33) | 2.0 (1.53, 2.69) | 0.8 (0.58, 1.21) |

| Reasons for last PO misuse | |||

| Relieve pain | 1.3 (1.00, 1.74) | 1.0 (0.76, 1.27) | 0.7 (0.54, 1.03) |

| Feel good or get high | 0.9 (0.58, 1.29) | 1.5 (1.27, 1.86) | 1.8 (1.22, 2.59) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. The sample size was n = 4403. Estimates are weighted; sample sizes are unweighted.

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, family income, marital status, metropolitan area, delinquency, major depressive episode, inpatient mental health treatment, took medication for mental health condition, health conditions lifetime, perceived health, emergency room visits past 12 months, health insurance, and survey year were controlled.

Gender Differences

Although men were more likely than women to misuse POs (for men, 4.8%; 95% CI = 4.5%, 5.1%; for women, 3.7%; 95% CI = 3.5%, 3.9%), rates of PO use disorder among misusers did not differ by gender. Across all PO user and misuser groups, men had higher rates of cocaine use than did women. Compared with men, women perceived greater risk from using drugs and were more likely to use benzodiazepines medically, to be depressed, and to take a prescribed medication for a mental health condition (Table D, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Controlling for all characteristics, female without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely than men to be Hispanic (AOR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.00, 2.94). Compared with medical users, female with-prescription-only misusers were more likely than men to have received inpatient mental health treatment (AOR = 4.5; 95% CI = 1.56, 12.79; Table E, model 1, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Male with-prescription-only misusers were more likely to misuse POs to relieve pain than were other misusers; there were no differences among female misusers (for interaction effect of with-prescription-only vs without-prescription-only misuser groups by gender, AOR = 2.9; 95% CI = 1.64, 5.02; for interaction effect of with-prescription-only vs without-and-with-prescription misuser groups by gender, AOR = 1.9, 95% CI = 1.02, 3.62; online Table E, model 2).

DISCUSSION

We examined prescription opioid medical users and misusers, differentiated according to whether they had a prescription, in a nationally representative sample of adults. We identified 3 misuser groups: misusers without prescriptions only, misusers of their own prescriptions only, and misusers with both types of misuse. The majority (88%) of past-12-month PO users were medical users; a minority (12%) were misusers. Among misusers, almost 60% had misused their own POs, whether exclusively or with prescribed opioids obtained without a prescription from a nonmedical source.

The most striking difference between PO misusers and medical users was the greater prevalence of substance use and disorder and of psychiatric comorbidity among misusers than among medical users. Prior reports that differentiated misusers by PO disorder13,14 found that misusers, especially those with PO disorder, had higher rates of substance use and disorder and of psychiatric problems than did those without disorder. The current study, which differentiated misusers by type of PO misuse, showed that although misuser groups differed from medical users on substance use and disorder and on mental and physical health, there were fewer differences among misuser groups, when we controlled for PO use disorder and reasons for misuse, variables not measured among medical users.

Without-and-with-prescription and with-prescription-only misusers were more likely to have a PO use disorder than were without-prescription-only misusers. Misusers without a prescription, whether they also misused their own prescriptions, were more likely to use marijuana and to misuse benzodiazepines than were exclusive misusers of their own prescriptions. Without-and-with-prescription misusers had the highest rates of heroin use. With control for PO use disorder, the differences regarding heroin use and benzodiazepine misuse between without-and-with-prescription and without-prescription-only misusers were attenuated. Without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to misuse multiple PO drugs (e.g., fentanyl, buprenorphine) than were other groups. Elevated buprenorphine misuse among without-and-with-prescription misusers is notable because it is prescribed to treat opioid use disorder.22

Although misusers did not differ in their health conditions, with-prescription-only misusers were more likely to visit an emergency room. Using POs to alleviate pain was the most common reason for misuse, especially among misusers of their own prescriptions only. Without-and-with-prescription misusers were more likely to misuse to feel good or get high than were other misuser groups. Failure to obtain pain relief from medical regimen is a major motivating factor for opioid misuse and underscores the urgent need for patients’ access to effective pain management. For chronic pain, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the use of nonpharmacological and nonopioid therapies by themselves or in combination with prescription opioids.23

Studies based on administrative records document elevated rates of substance use, psychoactive medication use, and mental health problems among patients prescribed opioids. Patients with these comorbidities are more likely to progress to long-term use, become misusers, and experience a nonfatal overdose.24–28 Investigations of PO overdose deaths indicate that 49% to 87% of decedents had been prescribed a PO in the year preceding death; over half had been prescribed benzodiazepines or other psychoactive drugs. Among decedents, those prescribed opioids had higher rates of substance use and psychiatric disorders than did nondecedents.29–33 Death records do not indicate whether decedents had misused their own POs or obtained POs without prescriptions. In 1 study, next of kin reported that decedents had misused POs prior to death.32 Furthermore, 61.4% of PO deaths in 2017 were comorbid with 1 of 5 other drugs. In the current analyses, we found that those who misused both their own prescriptions and prescription opioid drugs not prescribed to them had higher rates of prescription opioid use disorder, heroin use, and benzodiazepine misuse, a very hazardous pattern of substance use. The use of benzodiazepines in combination with prescription opioids is especially dangerous because of the increased risk of overdose death resulting from pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions leading to respiratory depression.34–36 Death rates are substantially higher among those prescribed both drugs than among those prescribed opioids alone.31,37,38 Thus, we infer that the majority of PO overdose deaths may occur among those who misuse both their own prescriptions and opioid drugs not prescribed to them.

Strengths and Limitations

Using a nationally representative sample of adults, this study differentiated types of PO misusers by whether they had a prescription. The study, based on self-reported data, provides a unique understanding of the characteristics of PO users by type of misuse and complements information obtained from administrative records. The findings that a high proportion of misusers misused their own prescriptions, and that these misusers were more likely to have a PO use disorder, highlight the role of medical use in the development of PO misuse and disorder, and underscore the need for longitudinal studies of prescription opioid users. Research on the natural history of medical and nonmedical PO use is needed to identify who starts using POs, who misuses with and without a prescription of their own, what factors predict different pathways to misuse, and who is most at risk for overdose and death. These factors would include ages of onset of medical use and misuse, prescribing patterns, pain levels, medical conditions, psychiatric disorders, other substance use, familial substance use, and biological vulnerability. Except for the assessment of substance use, the lack of such data and the cross-sectional design are limitations of the NSDUH. Other limitations include the exclusion of individuals with potentially higher rates of substance use from the sample, low completion rates, self-reports of substance use that are subject to underreporting, and DSM-IV rather than DSM-5 depression and substance use disorder diagnoses.

Public Health Implications

From a public health perspective, our findings suggest that strategies to reduce PO harm must consider different types of users and misusers. Physicians need to conduct thorough assessments of patients’ PO use patterns and history, other substance use, and psychiatric status, and make appropriate referrals, especially for psychiatric treatment. Implementing prescribing practices recommended by the CDC is a priority.23 The finding that 88% of without-prescription-only misusers and 57% of without-and-with-prescription misusers obtained their PO drugs from a friend or relative underscores the need for policies to reduce PO medication sharing and diversion.3,10

Prescription opioid misusers were characterized by high rates of substance use. Misusers of both their own prescribed opioids and opioid drugs not prescribed to them were especially likely to use heroin and misuse benzodiazepines, and may be most at risk for adverse PO outcomes, including overdose. These misusers may constitute an important but unmeasured component of prescription opioid overdose deaths. The current results underscore the importance of considering PO use within the context of the use of other substances. PO misuse is a polysubstance use problem.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grant R01 DA036748 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (D. B. K., principal investigator). Support was also provided by the New York State Psychiatric Institute (P. C. G.).

Note. The National Institute on Drug Abuse had no role in the study’s design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in the writing and submission of the article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study involved secondary data analysis of publicly available de-identified data and was granted expedited approval by the New York State Psychiatric Institute–Columbia University Department of Psychiatry institutional review board.

Footnotes

See also Heins, p. 1166.

REFERENCE

- 1.Guy GP, Zhang K, Bohm MK et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pezalla EJ, Rosen D, Erensen JG, Haddox JD, Mayne TJ. Secular trends in opioid prescribing in the USA. J Pain Res. 2017;10:383–387. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S129553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, Cai R. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 years in the United States, 2003–2013. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1468–1478. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu M-C, Griesler P, Wall M, Kandel DB. Age-related patterns in nonmedical prescription opioid use and disorder in the US population at ages 12–34 from 2002 to 2014. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419–1427. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm675152e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth P, Rudd RA, Noonan RK, Haegerich TM. Quantifying the epidemic of prescription opioid overdose deaths. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):500–502. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kandel DB, Hu MC, Griesler P, Wall M. Increases from 2002 to 2015 in prescription opioid overdose deaths in combination with other substances. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;178:501–511. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green TC, Black R, Serrano JMG, Budman SH, Butler SF. Typologies of prescription opioid use in a larger sample of adults assessed for substance abuse treatment. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ries R, Krupski A, West II et al. Correlates of opioid use in adults with self-reported drug use recruited from public safety-net primary care clinics. J Addict Med. 2015;9:417–426. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Sources of prescription opioid pain relievers by frequency of past-year nonmedical use: United States 2008–2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):802–803. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saloner B, Bachhuber M, Barry CL. Physicians as a source of medications for nonmedical use: comparison of opioid analgesic, stimulant, and sedative use in a national sample. Psych Serv. 2017;68(1):56–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes A, Williams MR, Lipari RN, Bose J, Copello EAP, Kroutil LA. Prescription drug use and misuse in the United States: results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2016. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR2-2015/NSDUH-FFR2-2015.htm. Accessed June 1, 2017.

- 13.Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Crane E, Lee J, Jones CM. Prescription opioid use, misuse, and use disorders in US adults: 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(5):293–301. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winkelman TNA, Chang VW, Binswanger IA. Health, polysubstance use, and criminal justice involvement among adults with varying levels of opioid use. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180558. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mazure CM, Fiellin DA. Women and opioids: something different is happening here. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):9–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serdarevic M, Striley CW, Cottler LB. Sex differences in prescription opioid use. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(4):238–246. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological Summary and Definitions. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Public Use File Codebook. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2018.; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiffman S, Waters A, Hickox M. The nicotine dependence syndrome scale: a multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(2):327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Final Approved CAI Specifications for Programming (English Version) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surrat HL, Kurtz SP. Factors contributing to the rise of buprenorphine misuse: 2008–2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1–49. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell CI, Bahorik AL, VanVeldhuisen P, Weisner C, Rubinstein AI, Ray GT. Use of a prescription opioid registry to examine opioid misuse and overdose in an integrated health system. Prev Med. 2018;110:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbert BT, Davis RB, Wee CC. Disproportionate longer-term opioid use among US adults with mood disorders. Pain. 2016;157(11):2452–2457. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn PD, Hur K, Chang Z et al. Incident and long-term opioid therapy among patients with psychiatric conditions and medications: a national study of commercial health care claims. Pain. 2017;158(1):140–148. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan M. Depression effects on long-term prescription opioid use, abuse, and addiction. Clin J Pain. 2018;34:878–884. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gladstone EJ, Smolina K, Weymann D, Rutherford K, Morgan SG. Geographic variations in prescription opioid dispensations and deaths among women and men in British Columbia, Canada. Med Care. 2015;53(11):954–959. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, Crystal S, Blanco C. Service use preceding opioid-related fatality. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(6):538–544. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17070808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dasgupta N, Funk MJ, Proescholdbell S, Hirsch A, Ribisi KM, Marshall S. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):85–98. doi: 10.1111/pme.12907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson EM, Lanier WA, Merrill RM et al. Unintentional prescription opioid-related overdose deaths: description of decedents by next of kin or best contact, Utah, 2008–2009. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(4):522–529. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohnert ASB, Valenstein M, Blair MJ et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315–1321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jann M, Kennedy WH, Lopez G. Benzodiazepines: a major component in unintentional prescription drug overdoses with opioid analgesics. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27(1):5–16. doi: 10.1177/0897190013515001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: a review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1–2):8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Babalonis S, Walsh SL. Warnings unheeded: the risks of co-prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines. Pain: Clinical Updates. 2015;23:1–7. Available at: https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/FileDownloads/ClinicalUpdates/PCU%2023-6.WebFINAL.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2019.

- 37.Jones CM, McAninch JK. Emergency department visits and overdose deaths from combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(4):493–501. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: case–cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2698. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]