Food insecurity is a significant public health problem in the United States. It affects large segments of the population (31% of low-income US households experienced food insecurity in 20171) and leads to an array of negative health consequences, including obesity and depression. However, relationships between food insecurity and health care utilization and expenditures have received relatively limited attention. Compared with their food-secure counterparts, individuals with food insecurity postpone needed medical care and medications more often,2 use more emergency and inpatient care,3 and have higher care expenditures by as much as 121%.3

In this issue of AJPH, Himmelstein (p. 1243) adds to our understanding of the associations between food insecurity and health care. However, whereas most studies in this area have focused on the negative effects of food insecurity on health care outcomes, Himmelstein examines an inverse question: can health insurance have a positive effect on the problem of food insecurity? The study used the differing choices states made regarding whether to expand Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act to assess the effects of gaining health insurance on food insecurity among low-income childless adults younger than 65 years. Comparing food insecurity among these individuals in expansion and nonexpansion states before and after expansions took place, the author found that very low food security (the most severe form of food insecurity measured for adults) declined in expansion states by 2.2 percentage points relative to nonexpansion states. To translate this into practical terms on the basis of how much insurance coverage increased in expansion versus nonexpansion states, the author estimated that very low food security was reduced by 0.4 percentage points for every 1.0 percentage point increase in insurance coverage.

Literature related to the social determinants of health typically focuses on how negative social conditions such as food and housing insecurity lead to negative health and health care outcomes. By focusing on the positive effects of health insurance on food insecurity, the author highlights how a positive change in health care systems was associated with a positive change in a social outcome. This framing switch is critical for two reasons. First, existing programs to address social ills such as food insecurity are often underfunded. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly the Food Stamp Program) has been found to reduce food insecurity at current levels, but only partially: most recipients still experience food-related hardships.4 Consequently, understanding how health policy changes may affect food insecurity introduces new possibilities for creating positive change. Second, health care systems shifting away from fee-for-service payment models and toward accountable care and Medicaid managed care models have incentives to address such social determinants of health as food insecurity3 that substantially influence high-cost health care utilization. To act deliberately in this area, however, these systems will need a more thorough understanding of the specific benefits that certain approaches might yield.

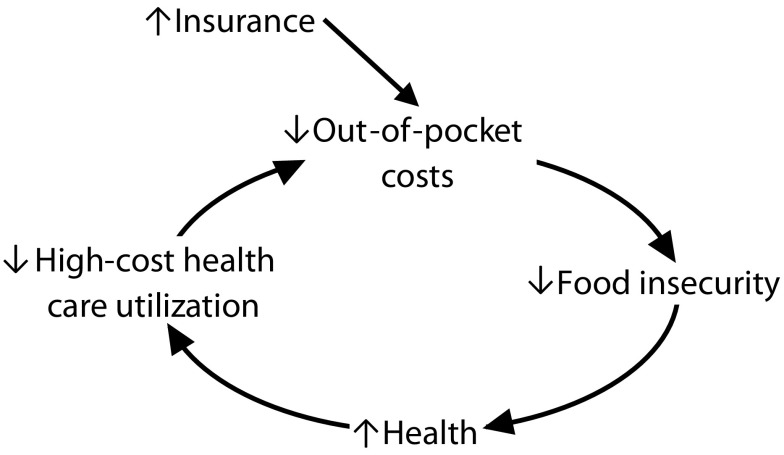

To that end, Himmelstein’s findings offer an example of evidence that can be used to think through potential interventions. In particular, the findings reveal the potential of helping individuals obtain health insurance coverage to spark a virtuous (as opposed to vicious) cycle that improves not only food insecurity but also health and health care outcomes.

POTENTIAL FOR A VIRTUOUS CYCLE

The author hypothesizes that the observed reductions in food insecurity after increased health insurance coverage were most likely driven by reduced out-of-pocket health care expenditures. Extending this hypothesis by using findings from previous studies3,5,6 exploring the relationships between food insecurity, health, high-cost health care utilization, and out-of-pocket costs, one can theorize that a potential virtuous cycle between these factors could be facilitated by an increase in health insurance coverage. Figure 1 summarizes such a cycle. Himmelstein provides evidence that Medicaid coverage is associated with a reduction in food insecurity and hypothesizes mediation through out-of-pocket costs. Next, food insecurity is associated with poor health outcomes and high-cost health care utilization, as I noted.3 And finally, especially among high-utilization populations, there is evidence linking the high health care needs of these populations to both greater out-of-pocket costs and higher levels of food insecurity.5,6

FIGURE 1—

Theorized Virtuous Cycle Sparked by Increased Health Insurance Coverage

One such high-utilization group in which assessing this theory may yield particularly valuable insights is the population of individuals with disabilities. Compared with people without disabilities, people with disabilities have elevated health care needs, high out-of-pocket expenditures, and 2.8 times the likelihood of experiencing food insecurity.6 Moreover, because of their health care needs, people with disabilities are less able than are individuals without disabilities to postpone or avoid health care services during periods of uninsurance.6 Any effects of health insurance coverage on food insecurity should thus be elevated in this population.

Furthermore, there are ample opportunities for health care systems to provide interventions targeting the health insurance enrollment of individuals with disabilities. Under the Affordable Care Act, enrollment outreach efforts to people with disabilities across states was variable, even among expansion states, and disability status is still associated with elevated rates of uninsurance despite some improvements after Medicaid expansion.7 Even in expansion states like California, which has robust enrollment efforts, and even with financial incentives among safety net hospitals to help uninsured individuals obtain coverage, community organizations such as Los Angeles County’s Children’s Health Outreach Initiative operate beyond capacity helping eligible individuals enroll in Medicaid. These individuals are disproportionately socially vulnerable. Thus, for Medicaid accountable care organizations and Medicaid managed care organizations, investing in greater outreach efforts to reduce uninsurance among individuals with disabilities in their service areas could allow them to test and potentially benefit from the relationships outlined in Figure 1.

LIMITS AND NEXT STEPS

It is important to think through the limits of the cyclical pathway theorized in Figure 1 and the potential effects of the factors it ignores. For example, although food insecurity is a key social determinant of health, it is one of many that interact with each other in complex ways. At some point, reductions in food insecurity will have diminishing health returns as other social factors (e.g., housing insecurity, social isolation) remain and prevent further gains. How quickly these returns might diminish is unclear. Also, many health and social policies at the community, state, and federal levels relevant to low-income populations can powerfully affect each point along the cycle in positive or negative ways. Preserving, cutting, or expanding Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and other public benefits—or succeeding or failing to reduce the share of health care costs paid for by health care consumers—could work to mute or amplify the connections in Figure 1, independently or in association with increases or decreases in the rates of health insurance coverage. Changes in wage growth attributable to government policies, independent corporate actions, or macroeconomic forces may also play an outsized role.

In part because of these complexities, however, efforts to explicitly test these links are warranted. For policymakers to fully understand the impact of proposed policies related to health care systems and social safety net programs, investigating the mechanisms through which these policies interrelate in potentially positive or detrimental ways will be critical. Doing so may help target policies to promote virtuous cycles while avoiding vicious ones for vulnerable populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant R03HS026317).

The author thanks Reginald Tucker-Seeley of the University of Southern California and Lara Bishay of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles for their thoughtful and constructive advice.

Note. The content of this editorial is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

See also Himmelstein, p. 1243.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food insecurity in the United States in 2017. 2017. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/90023/err-256.pdf?v=0. Accessed June 21, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mayer VL, McDonough K, Seligman H, Mitra N, Long JA. Food insecurity, coping strategies and glucose control in low-income patients with diabetes. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(6):1103–1111. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015002323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, Dachner N, Gundersen C, Kurdyak P. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CAMJ. 2015;187(14):E429–E436. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nord M, Golla AM. Does SNAP decrease food insecurity: untangling the self-selection effect. 2009. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/46295/10977_err85_1_.pdf?v=42317. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- 5.Huang J, Guo B, Kim Y. Food insecurity and disability: do economic resources matter? Soc Sci Res. 2010;39(1):111–124. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman-Jensen A, Nord M. Food Insecurity Among Households With Working-Age Adults With Disabilities. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture; 2013. Economic Research Report 144. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kayes HS. Disability-related disparities in access to health care before (2008–2010) and after (2015–2017) the Affordable Care Act. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(7):1015–1021. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]