Abstract

There has been a burst of research on immigrant health in the United States and an increasing attention to the broad range of state and local policies that are social determinants of immigrant health. Many of these policies criminalize immigrants by regulating the “legality” of their day-to-day lives while others function to integrate immigrants through expanded rights and eligibility for health care, social services, and other resources.

Research on the health impact of policies has primarily focused on the extremes of either criminalization or integration. Most immigrants in the United States, however, live in states that possess a combination of both criminalizing and integrating policies, resulting in distinct contexts that may influence their well-being.

We present data describing the variations in criminalization and integration policies across states and provide a framework that identifies distinct but concurrent mechanisms of deportability and inclusion that can influence health. Future public health research and practice should address the ongoing dynamics created by both criminalization and integration policies as these likely exacerbate health inequities by citizenship status, race/ethnicity, and other social hierarchies.

Conceptual models about the impact of immigrant policies on health have not kept up with the proliferation of policies over the past 20 years. There has been a burst in research on immigrant health in the United States and an increasing attention to the broad range of state and local policies that are social determinants of health.1 This research has primarily focused on individual restrictive (e.g., police collaboration with immigration enforcement) or inclusionary (e.g., access to health care) policies.2,3 Most states and localities, however, possess a mix of policies: those that are restrictive and criminalize immigrants by regulating the “legality” or permissibility of their lives, putting day-to-day activities like working and driving under the surveillance and control of immigration enforcement, and those that are inclusive and integrate immigrants by expanding eligibility and rights, facilitating access to health care, social services, education, and workplaces.4 In this article, we used state-level data and a framework to consider how the intersections of criminalization and integration policies may create distinct mechanisms that shape health.

Criminalization policies create mechanisms of surveillance and immigration enforcement that put noncitizens at risk for deportation. All noncitizens experience deportability—“the protracted possibility of being deported”5(p14)—and contend with uncertainty regarding their ability to remain in the country, even when they have a green card or naturalize.6,7 They are also targeted because of racialized concepts of immigrants of color as either criminals or exploitable workers,8,9 creating inequitable policy impacts based on legal status and race/ethnicity. For example, 95% of people deported are from Latin America, although only an estimated 75% of undocumented immigrants are from Latin America.10,11 The result of criminalization policies are mechanisms that can create acute stressors, as well as long-term patterns of discrimination that marginalize immigrants’ racial and legal status position.

Integration policies, by contrast, expand mechanisms of eligibility and rights that incorporate immigrants into society, facilitating access to health-promoting resources, regardless of citizenship status.12 Integration policies create inclusion by which noncitizens possess a similar constellation of rights, access, and protections as that of citizens. In contexts of inclusion, the inequality in rights between noncitizens and citizens is reduced.

CATEGORIZING POLICIES ACROSS STATES

An examination of policies across US states and the District of Columbia (hereafter “states”) illustrates patterns of how criminalization and integration policies coincide. We focus on state policies (e.g., legislation, regulations, court rulings) because, while the federal government has exclusive authority to regulate who enters the country and assign their legal status, states have discretion in how to apply a variety of public programs and policies to noncitizens. Each state’s contexts produce semi-independent influences on immigrants’ lives, allowing for comparative research to understand the impact of policy on health. Counties and localities have some discretion in areas such as policing and health care; they are often constrained, however, by state policies.13 While our focus is state policy, local policies also fit into the framework.

We conducted a systematic review of policies for which states have discretion to determine (1) rights based on citizenship or a proxy (e.g., possession of a social security number) and (2) the extent of collaboration with federal immigration enforcement. Table 1 presents the policies classified as criminalization or integration, organized by sector, and accompanied by the indicator used to assess if the policy existed. We classified 6 policies as criminalization because they shaped the authorization of noncitizens’ day-to-day activities (e.g., driving, seeking work), increasing their exposure to enforcement, and we classified 14 as integration because they conferred residents access to state institutions, regardless of citizenship status. These resided in sectors of identification and licensing, immigration enforcement and criminal justice, health and social service benefits, education, labor and employment, and language access.

TABLE 1—

State Immigrant Criminalization and Integration Policies by Sector, Enacted by December 31, 2015: United States

| Sector | Policy | Indicator That Policy Exists (Yes = 1; No = 0) |

| Criminalization policies | ||

| Identification and licensing | State driver’s licenses | Does the state require a social security number to obtain a driver’s license?14 |

| Compliance with the federal Real ID Act of 2005, which sets standards for state licenses and IDs | Does the state comply with Real ID?15 | |

| Work authorization | Use of employment authorization database, E-Verify | Does the state mandate employers use E-Verify?16 |

| Immigration enforcement and criminal justice | Law enforcement collaboration with federal enforcement | Does the state fully collaborate with federal immigration authorities?17 |

| Law enforcement inquiry about legal status | Does the state require or allow that law enforcement verify individuals’ legal status at the time of a stop or arrest?18 | |

| Sentencing laws | Does the state sentence nonviolent criminal offenses at least 365 d?18,a | |

| Integration policies | ||

| Health and social service benefits | State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) | Does the state provide health insurance to children regardless of legal status?19 |

| Medicaid—prenatal care | Does the state provide care to pregnant women regardless of legal status?19 | |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program | Does the state count a prorated share of ineligible noncitizen income to determine family eligibility for benefits?20 | |

| Education | In-state college and university tuition | Does the state provide most students in-state tuition regardless of legal status?21 |

| Financial aid for colleges and universities | Does the state provide students scholarships or financial aid regardless of legal status?21 | |

| Labor and employment | Citizenship requirements for peace officers | Does the state require peace officers be citizens?b |

| Citizenship requirements for teachers | Does the state require teachers be citizens?c | |

| Worker’s compensation | Does the state include undocumented immigrants in the definition of employee?22,a | |

| Extension of protections for agricultural workers | Does the state extend wage and hour protections for agricultural workers?23 | |

| Extension of protections for domestic workers | Does the state extend wage and hour protections for domestic workers?23 | |

| Domestic Worker’s Bill of Rights | Does the state have a Domestic Worker’s Bill of Rights?23 | |

| Protection against immigration-related employer retaliation | Does the state have laws that protect noncitizen workers from employer retaliation related to their legal status?24 | |

| Professional licensing of undocumented and DACAmented professionals | Does the state allow licensing of undocumented or DACAmented professionals?24 | |

| Language access | Payment of interpreters through Medicaid or SCHIP | Does the state pay for interpreters through Medicaid or SCHIP?25 |

| English language–only legislation | Does the state have English as the official language?26 |

Note. DACA = Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

And author’s review of state statutes.

Author’s review of state law enforcement agency hiring requirements and legislative codes.

Author’s review of state department of education hiring requirements and legislative codes.

The indicators established the criteria and scoring of whether a policy existed (yes = 1 and no = 0). These included the presence of a policy (e.g., state provides in-state tuition for qualified undocumented students) as well as lack of a policy (e.g., state prohibits undocumented immigrants from obtaining driver’s licenses by not having enabling legislation). We reviewed secondary sources to determine the existence of the policies in each state and included those enacted by December 31, 2015. We summed the total number of criminalization and integration policies separately, producing measures of overall context. The strength of this approach, used elsewhere, is that it considers the composition of a state’s environment; its limitation is that it does not account for variation in the impact of individual policies, although there is no established methodology to do so.27 Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides the number of policies per state. States had a median of 4 criminalization (mean = 3.5) and 4 integration policies (mean = 4.9).

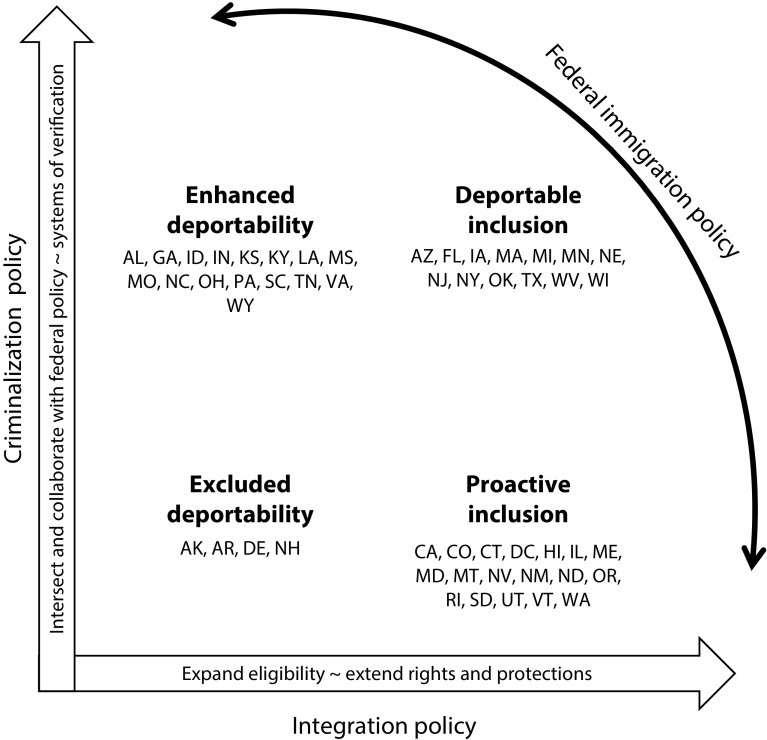

To show patterns of how criminalization and integration policies coincide in US states, we created 2 dichotomous variables at the median number of policies: states with 4 or more versus fewer than 4 criminalization policies and states with 4 or more versus fewer than 4 integration policies. Crossing these variables creates a typology of 4 policy context types: high integration, low criminalization (18 states); high integration, high criminalization (13 states); low integration, high criminalization (16 states), and low integration, low criminalization (4 states). Appendix B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides a map that shows states’ policy context type.

High-integration, high-criminalization states, such as New York and Texas, despite being politically and demographically different, subject noncitizens to potential surveillance and reinforce collaboration with federal immigration enforcement while also having policies that promote access to some health care, social welfare, education, and—to a lesser extent—labor and employment protections. When one considers only criminalization policies, a low-integration, high-criminalization state, such as Georgia, may appear like Texas or New York; however, in these states, noncitizens not only experience a heightened threat of surveillance, policing, or deportation but are also blocked from many rights and opportunities. By contrast, in high integration, low criminalization states, such as California, policy mechanisms expand rights and eligibility for resources that may advance well-being while actively buffering against criminalization. A handful of states had few policies of either type, indicating that they defer to the default federal mix of criminalization and integration policies.

A FRAMEWORK OF HEALTH AND POLICY CONTEXTS

States that have multiple criminalizing policies create contexts in which immigrants experience greater deportability because state-level institutions and agencies reinforce enforcement and surveillance. States that have numerous integration policies create contexts in which immigrants experience greater inclusion because policymakers proactively increase access and rights within health, education, labor, and other sectors. Within each state, despite the level of criminalization, immigrants possess variable rights and eligibility for services; despite the level of integration, immigrants still face variable risks for deportation. Because of these distinct dynamics, immigrants may simultaneously experience deportability and inclusion in which states’ overall policy contexts coincide to produce a unique policy and social environment.

Figure 1 identifies the intersecting contexts of deportability and inclusion that immigrants experience living under the distinct but concurrent dynamics of criminalization and integration. The framework shows that the overall process by which immigrants experience criminalization or integration is the result of more than 1, not mutually exclusive, policy process. These experiences may unfold at the state or local level and always are embedded within the overarching, baseline federal immigration policy context, which in recent years is increasingly criminalizing and less integrating. The result is a policy-driven environment that shapes how immigrants’ daily lives unfold as they experience both threats of enforcement and a mix of resources that can improve their life chances in multiple domains.

FIGURE 1—

Framework of Immigrant Policy Contexts Created by Criminalization and Integration Policies: United States

States with high numbers of integration and criminalization policies create contexts of deportable inclusion. Noncitizens are subject to enforcement and surveillance while possessing rights and protections in other areas of their lives. In other words, the presence of many integration policies grants numerous rights and protections but does not curtail criminalization. States with numerous criminalization policies and few integration policies create contexts of enhanced deportability in which noncitizens face enforcement and surveillance with few rights, protections, or eligibility for the services that citizens receive. The presence of few criminalization policies and few integration policies creates contexts of excluded deportability in which noncitizens are subject to the federal baseline of relatively exclusionary policies. Finally, in states with numerous integration policies and few criminalization policies, the context is one of proactive inclusion in which noncitizens are buffered from deportability and proactively included. In states such as California or Washington, immigrant incorporation is based not solely on expansion of rights and protections but also on decriminalization.

The experience of deportable inclusion, enhanced deportability, excluded deportability, and proactive inclusion are likely related to distinct health mechanisms. First, in contexts of deportable inclusion and enhanced deportability, surveillance and enforcement may limit or nullify the positive public health impact of any or all integration efforts in access to health care and social services, educational opportunities, or workplace protections. This concern has been the primary focus of recent public health research on immigrant policy. Deportability results in entire immigrant populations experiencing uncertainty and discrimination, regardless of how many individuals ultimately experience direct surveillance, enforcement, and deportation.5 For example, immigrants experience immediate barriers to health care, such as concerns about driving to medical visits or distrust of health care and other providers.28–30 In addition, research shows that the specter of deportability can result in a racialized environment that is harmful to people of color, regardless of citizenship status. One study found that Latinos, regardless of nativity or citizenship, were targeted by immigration enforcement because of their ethnicity.31 Deportability, regardless of inclusion, has a wide-reaching, even universal, impact on populations based on their citizenship status or race/ethnicity.

Another possible dynamic at the intersection of criminalization and integration is that health inequities between noncitizens, not only in comparison with citizens, are exacerbated in contexts of deportable inclusion and proactive inclusion. The harms and benefits of criminalization and integration policies are not equally distributed. Integration may be accessed more easily by some noncitizens while, in practice, others are more often criminalized. In these states, the processes of racialization and “deserved” incorporation may produce or reinforce inequities among noncitizens based on factors such as race/ethnicity, gender, age, and class (e.g., employment sector or access to education).5,31,32 Despite the wide-reaching effects of deportability, specific immigrant populations remain the most vulnerable to criminalization.9,33 These vulnerabilities to deportation are not random but are shaped by social hierarchies. For example, extensive research has demonstrated how immigrant day laborers experience extreme structural disadvantage at the intersection of legal status, race, gender, and socioeconomic status.33

The division of immigrant populations into those who are labeled “criminals” and those who are labeled “deserving” places noncitizens who may share the same legal status into distinct and inequitable social positions—each with unique and varying risks to their well-being. For example, policies to limit law enforcement collaboration with immigration enforcement tend to exclude certain classes of criminal offenders (e.g., those who committed felonies), perpetuating the risk of deportation for some immigrants who are involved in the criminal justice system and their families, while producing a potential sense of safety among others who can then more readily benefit from integration policies. The dual dynamics of criminalization and integration likely increase inequities not only between citizens and noncitizens but also within categories of noncitizens, as the motivations and targets of these policies reinforce race, gender, and class inequities within immigrant groups.

These dynamics point to future directions for research, practice, and advocacy. Because criminalization and integration policies have distinct characteristics and implications, it is important in research not to combine them into a single construct and in public health practice to pursue action in both domains. Research can assess the competing influences of criminalization and integration on health outcomes. To what extent does criminalization policy harm the benefits of integration policy and how could integration policy buffer the impact of criminalization? Although current research shows a negative impact of criminalization policies, this has not been examined in the context of existing integration policies. Research can also examine variations in the impact of policies on different racial/ethnic groups, as well as other structural factors such as gender and class. Most research has exclusively focused on Latinos, despite the rapid growth of migration from Asia.

In addition, studies of single policies suggest spillover effects from criminalizing state immigrant policy adoption on the health of nonimmigrants.30 While there is a logical link between criminalizing immigrant policies with generalized stress and discrimination throughout the population, there is also a theoretical link that has not yet been tested between integrating state immigration policies and broader community health.34 Finally, immigrant integration is likely to have positive effects on people’s ability to contribute to the larger community through greater social mobility, which leads to paying more taxes and greater community engagement. But the spillover effects of the interaction between the criminalizing and integrating policies remains an open question.

The state immigrant policy data in Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides a tool to assess criminalization and integration as distinct constructs. Research on the intersection of these policies can inform public health practitioners who are developing policies and interventions. Practitioners can assess the extent to which public health programs are able to advance health despite criminalizing contexts. Recent efforts include health clinics establishing “sanctuary policies” and the development of a guide for health departments to protect people from immigrant enforcement actions.35,36 At the policy level, as advocates advance health and other social policies, they can adapt policies to include elements of decriminalization to ensure that integration policies do not exclude groups targeted by criminalization policies. Researchers, practitioners, and advocates can advance efforts to reduce the deportability of all groups of immigrants toward improving health and well-being and achieving health equity.

CONCLUSIONS

Patterns of state-level criminalization and integration show that most jurisdictions are not exclusively criminalizing or integrating. Rather, they create contexts in which noncitizens may experience enhanced deportability or proactive inclusion but also deportable inclusion or excluded deportability. The dual processes of criminalization and integration may exacerbate social, economic, and health disparities by citizenship status within immigrant populations based on race/ethnicity and other social hierarchies and have spillover effects to the broader community.37 Criminalization policies at state and local levels reinforce federal immigration enforcement, giving state or local governments a de facto role in shaping federal deportation policies.38 Integration policies, by contrast, expand noncitizens’ rights to accessing certain resources regardless of citizenship but do not buffer individuals against enforcement or surveillance.

It is likely that varied, and even contradictory, state and local immigrant policies will continue to be enacted as existing policies continue to shape immigrants’ well-being. It will be critical for public health researchers and practitioners to understand the unique impact of mixed policy environments, as immigrants and their families navigate the complexities of criminalization and integration in their daily lives. Both integration and decriminalization are necessary for achieving health equity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant R01MD012292-02.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

We declare no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review board approval was not needed because no human participants were involved in the research.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Perreira KM, Pedroza JM. Policies of exclusion: implications for the health of immigrants and their children. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):147–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace SP, Young ME, Rodríguez MA, Brindis CD. A social determinants framework identifying state-level immigrant policies and their influence on health. SSM Popul Health. 2018;7:016–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philbin MM, Flake M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hirsch JS. State-level immigration and immigrant-focused policies as drivers of Latino health disparities in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inclusive policies advance dramatically in the states immigrants’ access to driver’s licenses, higher education, workers’ rights, and community policingLos Angeles, CA: National Immigrant Law Center; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Genova N, Peutz NM. The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanstroom D. Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzei P. Congratulations, you are now a US citizen. Unless someone decides later you’re not. New York Times. July 23, 2018. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/23/us/denaturalize-citizen-immigration.html. Accessed February 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willen SS. Migration, “illegality,” and health: mapping embodied vulnerability and debating health-related deservingness. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golash-Boza T, Hondagneu-Sotelo P. Latino immigrant men and the deportation crisis: a gendered racial removal program. Lat Stud. 2013;11(3):271–292. [Google Scholar]

- 10.2016 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security; [Google Scholar]

- 11.Passel JS, Cohn DV. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; April 2009. A portrait of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motomura H. Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vock DC. The end of local laws? War on cities intensifies in Texas. Governing. April 5, 2017. Available at: https://www.governing.com/topics/politics/gov-texas-abbott-preemption.html. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 14.National Council of State LegislaturesImmigrant Policy Project. States offering driver’s licenses to immigrants2016Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/states-offering-driver-s-licenses-to-immigrants.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Council of State Legislatures. State legislative activity in opposition to the Real ID. January 2014. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/documents/standcomm/sctran/REALIDComplianceReport.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 16.National Council of State Legislatures. State E-Verify action. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/immigration/everify-faq.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 17.Immigrant Legal Resource Center. National Map of Local Entanglement with ICE. Available at: https://www.ilrc.org/local-enforcement-map. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 18.García Hernández CC. Crimmigration Law. Washington, DC: American Bar Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Immigration Law Center. Health care coverage maps. Available at: https://www.nilc.org/issues/health-care/healthcoveragemaps. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 20.Supplemental Nutrition Assistance ProgramState options report10th editionUS Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; August 2012Available at: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/waivers/state-options-report. Accessed February 5, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Council of State Legislatures. Undocumented student tuition: state action. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/undocumented-student-tuition-overview.aspx. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 22.Schumann J. Working in the shadows: illegal aliens’ entitlement to state workers' compensation. Iowa Law Rev. 2004;89:709–739. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Employment Law Project. Winning wage justice: an advocate’s guide to state and city policies to fight wage theft. Available at: https://nelp.org/publication/winning-wage-justice-an-advocates-guide-to-state-and-city-policies-to-fight-wage-theft. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 24.National Immigration Law Center. Immigrant-inclusive state and local policies move ahead in 2014–15. Available at: https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/pro-immigrant-policies-move-ahead-2015-12.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 25.Youdelman M National Health Law Program. Medicaid and CHIP reimbursement models for language services. Available at: https://healthlaw.org/resource/medicaid-and-chip-reimbursement-models-for-language-services. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- 26.US English. State legislation. Available at: https://www.usenglish.org/legislation/state. Accessed February 4, 2019.

- 27.Marquez T, Schraufnagel S. Hispanic population growth and state immigration policy: an analysis of restriction (2008–12) Publius. 2013;43(3):347–367. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodes SD, Mann L, Siman FM et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):329–337. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toomey RB, Umana-Taylor AJ, Williams DR, Harvey-Mendoza E, Jahromi LB, Updegraff KA. Impact of Arizona’s SB 1070 immigration law on utilization of health care and public assistance among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):S28–S34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):839–849. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romero M. Crossing the immigration and race border: a critical race theory approach to immigration studies. Contemp Justice Rev. 2008;11(1):23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armenta A. Protect, Serve, and Deport: The Rise of Policing as Immigration Enforcement. Oakland, CA: University of California Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ordóñez JT. “Boots for my Sancho”: structural vulnerability among Latin American day labourers in Berkeley, California. Cult Health Sex. 2012;14(6):691–703. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.678016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Poortinga W. Community resilience and health: the role of bonding, bridging, and linking aspects of social capital. Health Place. 2012;18(2):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Public Health Awakened. Guide for Public Health Actions for Immigrant Rights. Available at: https://publichealthawakened.com/guide-for-public-health-to-protect-immigrant-rights. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- 36.McGahan J. L.A. 2017. health clinic protects immigrants against illness—and deportation. LA Weekly. March 15. Available at: https://www.laweekly.com/news/health-clinic-declares-itself-a-sanctuary-amid-rising-fear-of-deportations-8026443. Accessed June 5, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vargas ED, Sanchez GR, Juárez M. Fear by association: perceptions of anti-immigrant policy and health outcomes. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2017;42(3):459–483. doi: 10.1215/03616878-3802940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motomura H. Immigration Outside the Law. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]