Abstract

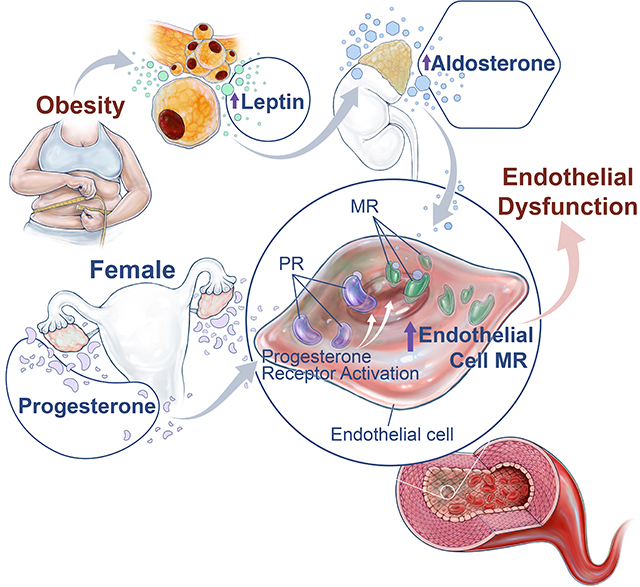

Compelling clinical evidence indicates that obesity and its associated metabolic abnormalities supersede the protective effects of female sex-hormones and predisposes premenopausal women to cardiovascular disease. The underlying mechanisms remain poorly defined; however, recent studies have implicated overactivation of the aldosterone-mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) axis as a cause of sex-specific cardiovascular risk in obese females. Experimental evidence indicates that the MR on endothelial cells contributes to obesity-associated, leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in female experimental models, however, the vascular-specific mechanisms via which females are predisposed to heightened endothelial MR activation remain unknown. Therefore, we hypothesized that endogenous expression of endothelial MR is higher in females than males which predisposes them to obesity-associated, leptin-mediated endothelial dysfunction. We found that endothelial MR expression is higher in blood vessels from female mice and humans compared to those of males, and further, that progesterone receptor activation in endothelial cells is the driving mechanism for sex-dependent increases in endothelial MR expression in females. In addition, we show that genetic deletion of either the endothelial MR or progesterone receptor in female mice prevents leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction, providing direct evidence that interaction between the progesterone receptor and MR mediates obesity-associated endothelial impairment in females. Collectively, these novel findings suggest that progesterone drives sex-differences in endothelial MR expression and predisposes female mice to leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction, which indicates that MR antagonists may be a promising sex-specific therapy to reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases in obese premenopausal women.

Keywords: sex differences, obesity, mineralocorticoid receptors, endothelial function, leptin, progesterone, endothelial cells

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

It is well understood that obesity is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD)1. While premenopausal women are typically protected from CVD, clinical data indicates that obesity can override that protection and is a more important driver of cardiovascular risk in women than in men 2. Emerging evidence suggests that the mechanisms by which obesity promotes CVD in females differ from those in males. Many studies have demonstrated that sympathetic activation mediates obesity-associated cardiovascular risk in males 3–7, however, sympathetic activation is not characteristically increased in premenopausal obese women 5, 7, 8, despite their increased risk for CVD. Therefore, other mechanisms must contribute to obesity-induced cardiovascular risk in premenopausal women, and without a better understanding of these mechanisms, this demographic is left with clinical approaches that may not be effective.

Accumulating evidence indicates that females are more sensitive to the development of obesity-associated impairment of vascular endothelial function than males 9–11, which is an established precursor for hypertension and other cardiovascular events 12, 13. Data in mice and humans indicates that endothelial dysfunction and increases in brachial pulse pressure occur more readily in response to obesity in female mice and humans, respectively, compared to age-matched males 10, 14. We have previously demonstrated that increased adipose tissue mass leads to increased leptin synthesis and leptin receptor activation which are crucial events that promote endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in female obese experimental models 9, 10. However, the underlying mechanisms whereby the female endothelium is more sensitive to hyperleptinemia in obesity are as yet unknown and are goals of the current study.

Experimental and clinical data suggest that mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) antagonists may be more efficacious for improvement of heart failure and hypertension outcomes in females compared to males 15, 16. In accordance with these findings, we and others have demonstrated that MR antagonism ablates arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in female obese and leptin-infused mice 9, 10, 17, 18. However, a vascular-intrinsic mechanism(s) that renders the female vasculature more sensitive to MR activation than that of males has yet to be postulated. Important recent studies demonstrate that selective knockout of the MR in the vascular endothelium of female mice prevents arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction on a high fat diet 19, 20. Collectively, these clinical and experimental data raise two important questions: (1) whether there is a female-specific physiological mechanism(s) whereby endothelial MR activity is increased in females and (2) whether endothelial MR signaling mediates obesity-associated, leptin-mediated endothelial impairment in females. We hypothesized that expression of the endogenous endothelial MR is upregulated by progesterone receptor activity in the vasculature of females which mediates heightened sensitivity to leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in females.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Experimental Animals

For our experiments, we utilized male and female wild-type Balb/C mice, obese Agouti mice as well as two mouse models of endothelial-specific deletion of MR and PrR. Details of mouse models and treatments utilized can be found in the online data supplement.

Statistics

Analyses were performed in Graphpad® Prism software (La Jolla, CA). Data are expressed as mean±S.E.M. In non-repeated variables, differences among means was verified by t-test with Kolmogrov-Smirnov test to verify normality. Parametric and non-parametric data with multiple means utilized one-way ANOVA with Kruskal-Willis test. Repeated variable measures with multiple data sets utilized two-way ANOVA. Tukey or Sidak post-hoc test followed all ANOVA. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Detailed description of the methods used is available in the online-only data supplement.

Results

Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor expression is increased in female mice compared to males

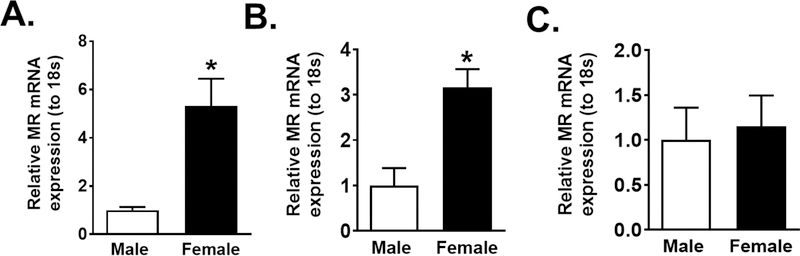

In Figure 1A we demonstrated that whole aortas from female mice express higher levels of MR mRNA than males. Subsequently, we used immuno-capture to isolate endothelial cells from male and female mice aorta, verified the phenotype of the cells (Figure S1) and demonstrated an increase in MR mRNA expression in endothelial cells from female compared to male mice (Figure 1B). In contrast, the non-endothelial vascular cell fraction exhibited no sex-difference in MR expression (Figure 1C), thereby indicating that sex-specific upregulation of MR in females is restricted in the vasculature to endothelial cells.

Figure. 1: Endothelial MR expression is increased in female compared to male mice.

MR mRNA expression in whole aorta homogenate (N=6) (A), endothelial cells (N=9) (B) or other non-endothelial vascular cells (N=9) (C) in male and female Balb/C mice. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. *P<0.05 vs Male, (Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

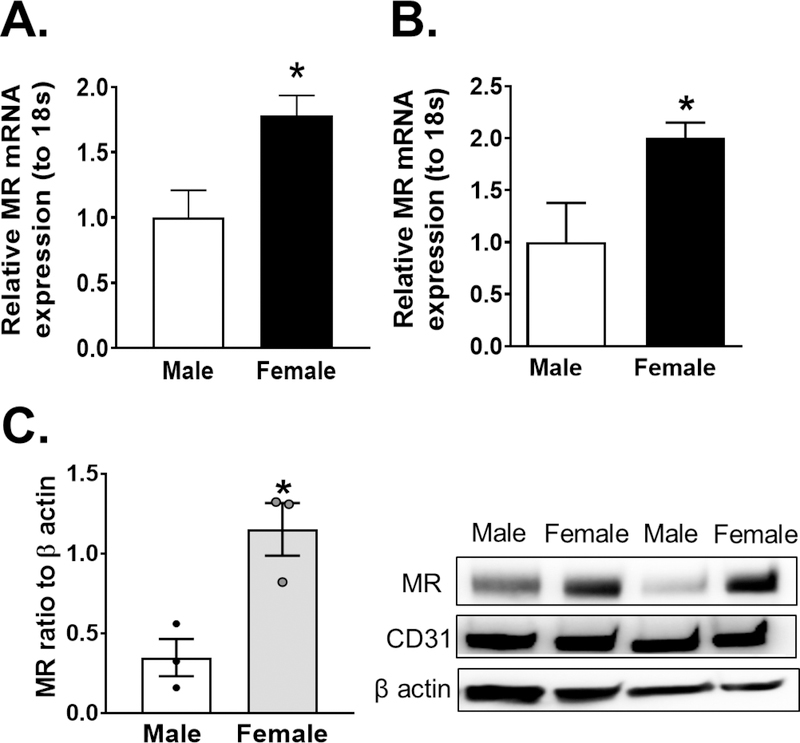

Expression of endothelial MR is increased in women compared to men

We next sought to investigate whether the sexual dimorphism in murine endothelial MR expression is conserved in humans. We demonstrated that MR mRNA expression increased in whole human adipose tissue arterioles from female patients as compared to males (Figure 2A) as well as in isolated adipose endothelial cells (Figure 2B). We confirmed that our endothelial isolation in adipose samples was successful via verification of CD31 expression in endothelial fractions and of PPARγ in adipocyte fractions (Figure S2). We further sought to determine if sex-differences in endothelial MR expression are more pronounced in young men and women, which mirrors the premenopausal status of our experimental female mice. As demonstrated in Figure 2C, primary cultured endothelial cells of young female patients express significantly more MR protein compared to males.

Figure. 2: Endothelial MR expression is increased in female patient samples compared to those from male patients.

MR mRNA expression in whole adipose arterioles (N=5) (A) and isolated adipose endothelial cells (N=6 male, 5 female) (B) of male and female patient samples. MR protein expression in cultured endothelial cells from young male and female donors (N=3) (C). Data are expressed as mean ±SEM.*P<0.05 vs Male, (Student’s t-test).

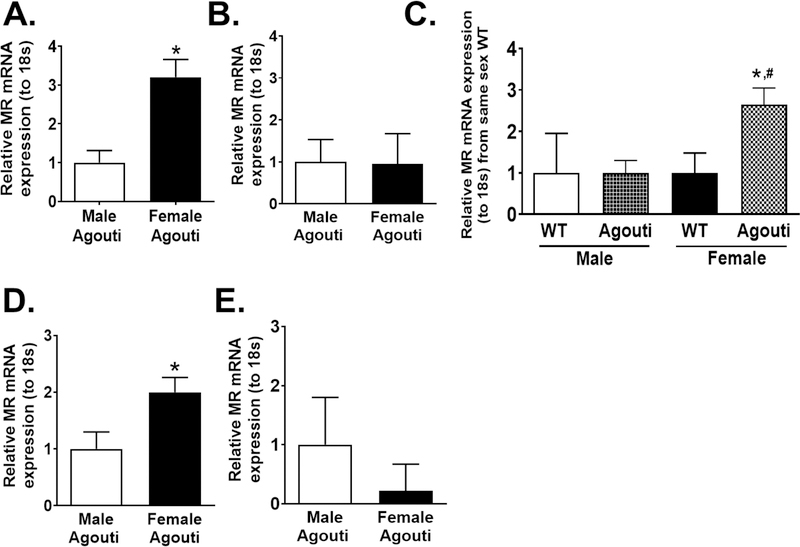

Endothelial MR expression is higher in female obese mice compared to males

We demonstrate in Figure 3A that MR mRNA expression is increased in the aorta of female obese Agouti mice compared to that of males while the non-endothelial vascular cells did not exhibit sex differences in MR expression (Figure 3B). Obesity as a factor did not increase the expression of MR in aortic endothelial cells from male mice, however, expression of MR was significantly increased with obesity in Agouti females (Figure 3C). Similar to findings in the aorta, expression of endothelial MR in the kidney was increased in obese Agouti female mice as compared to obese Agouti males (Figure 3D), however, no sex discrepancies in MR mRNA expression were seen in non-endothelial renal cells (Figure 3E). These data indicate that obesity increases endothelial MR expression in female mice only and in multiple vascular beds.

Figure. 3: Endothelial MR expression is increased in aorta and kidneys of obese Agouti female mice compared to obese Agouti males.

MR mRNA expression in endothelial cells (N=12) (A) and other vascular cells (N=6) (B) of aorta from male and female obese Agouti mice. MR mRNA expression of aorta endothelial cells of obese male and female Agouti mice compared to strain-matched wild-type (WT) (N=4 WT, 12 Agouti) (C). MR mRNA expression in kidney endothelial cells (N=6) (D) and non-endothelial kidney cells (E) in kidneys of male and female obese Agouti mice (N=6). Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. *P<0.05 vs Male, same-sex WT or same-sex non-endothelial renal cells, #P<0.05 vs Male Agouti (Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

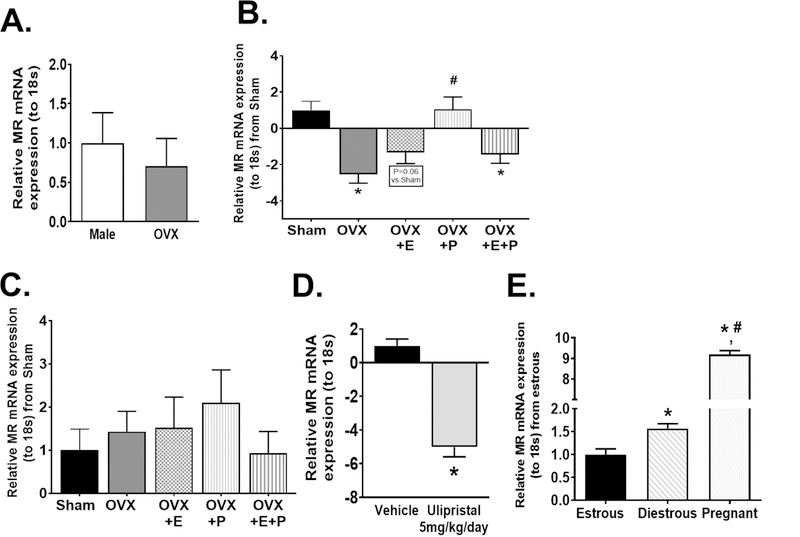

Progesterone receptor activation increases MR expression in mouse and human endothelial cells

We demonstrate that OVX in female mice ablated the sex difference in endothelial MR expression (Figure 4A) and decreased endothelial MR expression compared to Sham females (Figure 4B). Estrogen supplementation did not affect endothelial MR mRNA expression in OVX mice, however, progesterone supplementation alone restored endothelial MR expression in OVX mice to levels similar to those of Sham females (Figure 4B). In addition, we demonstrate that neither OVX nor hormone supplement affected MR expression in aorta non-endothelial cells (Figure 4C). Furthermore, the progesterone receptor antagonist Ulipristal significantly decreased endothelial MR expression in female mice (Figure 4D). In addition, we took advantage of the female menstrual cycle and show that, consistent with elevations in progesterone in diestrous 21, endothelial MR expression is increased during the diestrous phase as compared to the estrous phase (Figure 4E). Lastly, endothelial MR expression was greatly increased during pregnancy, in accordance with the highly elevated progesterone levels observed at day 16 of gestation (Figure 4E) 22. Collectively, these data indicate that progesterone drives increases in endothelial MR expression in females.

Figure 4: Sex differences in endothelial MR expression are ablated with ovariectomy and restored by progesterone.

MR mRNA expression in aorta endothelial cells of male and OVX mice (N=9) (A) as well as endothelial cells (B) and non-endothelial aorta cells (C) of sham (N=6), ovariectomized (OVX) (N=8), OVX+estrogen (E) (N=6), OVX+progesterone (P) (N=6) and OVX+E+P (N=6) female mice. MR mRNA expression in aorta endothelial cells of female mice treated with either vehicle or Ulipristal for 28 days (N=9 vehicle, 5 Ulipristal) (D). MR mRNA expression of aorta endothelial cells of female mice sacrificed in estrous, diestrous or during pregnancy (E) (N=6 estrous, 4 diestrous, 5 pregnant). Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. *P<0.05 vs Sham, vehicle or estrous, #P<0.05 vs OVX or diestrous, ΦP<0.05 vs OVX+P. (Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test).

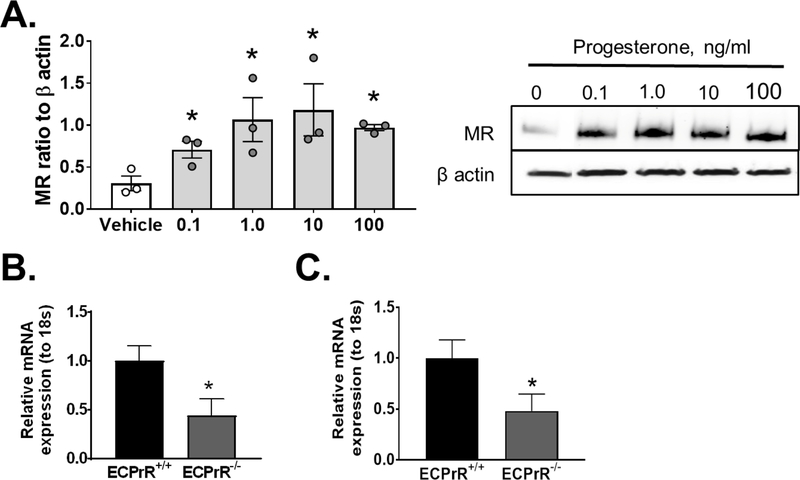

Endothelial progesterone receptor activation upregulates endothelial MR expression in a cell intrinsic manner

To determine whether progesterone acts directly at the endothelial cell level, endothelial cells in culture were submitted to progesterone. Progesterone supplementation at physiological doses ranges from 0.1ng/ml-100 ng/ml induced a significant upregulation of endothelial MR protein expression (Figure 5A). To evaluate this relationship in vivo, we generated mice with inducible knockout of the progesterone receptor (PrR) selectively in endothelial cells and reported that endothelial MR expression is blunted in mice with endothelial PrR deletion (Figure 5B, C), providing in vivo support of our in vitro data that endothelial MR upregulation by progesterone is driven by endothelial-specific PrR activation.

Figure 5: Endothelial progesterone receptor activation stimulates endothelial MR upregulation.

MR protein expression (A) in HUVEC cells treated with ascending doses of progesterone (0.1–100 ng/ml) for 24 hours (N=3). mRNA expression of PrR (N=15 ECPrR+/+, 10 ECPrR−/−) (B) and MR (N=12 ECPrR+/+, 9 ECPrR−/−) (C) in isolated aorta endothelial cells of wild-type (ECPrR+/+) and endothelial PrR knockout (ECPrR−/−) mice. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. *P<0.05 vs Vehicle or ECPrR+/+. (Student’s t-test).

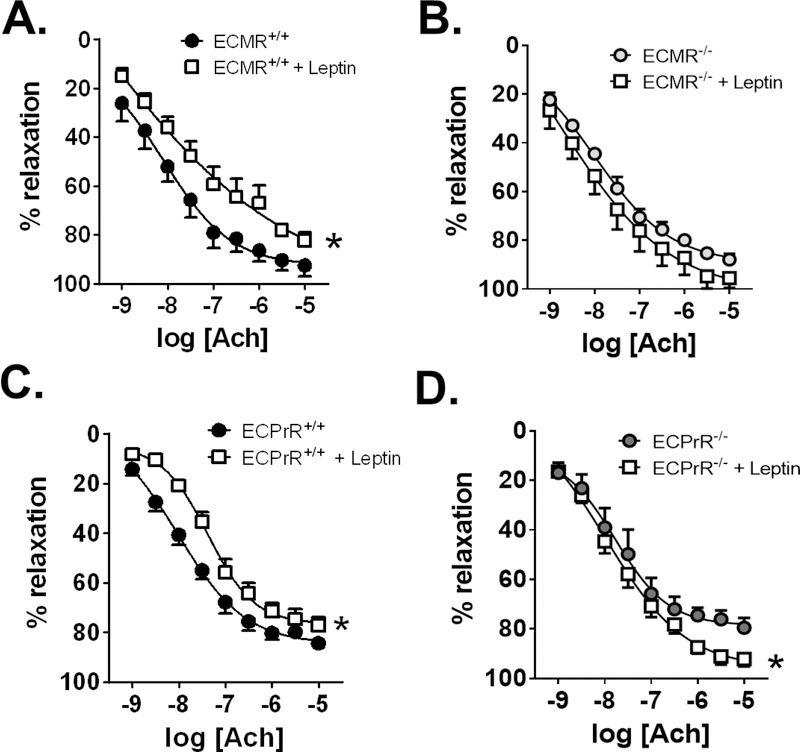

Endothelial MR deletion prevents leptin-mediated endothelial dysfunction in female mice

We have previously verified that leptin infusion increases plasma aldosterone and adrenal CYP11B2 (aldosterone synthase) expression in female mice 9 and induces endothelial dysfunction in female mice only 10. Consistent with our previous report, female wild-type littermates of endothelial MR knockout mice (ECMR+/+) mice developed endothelial dysfunction in response to leptin infusion (Figure 6A). In contrast, female mice lacking MR only in endothelial cells (ECMR−/−) were protected from leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction (Figure 6B). In male mice, leptin improved endothelial function in mice with intact MR (ECMR+/+), but not in mice lacking the endothelial MR (ECMR−/−), (Figure S3A, S3B). We further observed that sodium nitroprusside-induced relaxation was unaltered in female (Figure S4A, S4B) and male (Figure S4C, S4D) ECMR+/+ and ECMR−/− mice, indicating that protection from leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in female mice was derived from improvement of endothelial cell, but not smooth muscle cell, function. These data demonstrate for the first time that leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction is a unique pathway in female mice that requires expression of the endothelial MR.

Figure 6: Endothelial MR and PrR expression is required for leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in females.

Aorta relaxation responses to acetylcholine in female wild-type littermate (ECMR+/+) and endothelial MR knockout (ECMR−/−) mice (N=6) (A,B) and wild-type littermate (ECPrR+/+) and endothelial progesterone receptor knockout (ECPrR−/−) mice (N= 8 ECPrR+/+, 4 ECPrR+/+ +leptin, 5 ECPrR−/−, 6 ECPrR−/− +leptin) (C,D). Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. *P<0.05 vs Control. (Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test).

Endothelial Progesterone Receptor deletion protects from leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction

Based on our data that upregulation of the endothelial MR in female mice is driven by endothelial PrR activation, we investigated whether endothelial cell PrR deficiency protects from leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction. Leptin infusion into female mice with intact PrR (ECPrR+/+) impaired endothelial function (Figure 6C). However, leptin infusion failed to induce endothelial dysfunction in female mice lacking PrR only in the endothelium (ECPrR−/−), (Figure 6D). Furthermore, leptin did not reduce endothelial function in male ECPrR+/+ and ECPrR−/− mice (Figure S5C, S5D) and endothelium-independent relaxation responses to sodium nitroprusside in female and male ECPrR+/+ and ECPrR−/− mice were unaltered by leptin infusion (Figure S5A-D). Therefore, endothelial-specific deletion of PrR not only suppresses endothelial MR expression, but is required for leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in females.

Discussion

In the current study, we have uncovered a novel role for progesterone in the regulation of endothelial MR expression which provides a mechanistic pathway linking obesity and heightened cardiovascular risk in young females, a population that in the US alone comprises millions of women. While prior studies have implicated endothelial MR activation in the pathogenesis of vascular dysfunction in obese females 19, 20, the underlying mechanisms that lead to pathological signaling of the endothelial MR specifically in females have not been investigated to date. In this report, we provide evidence that endothelial progesterone receptor activation drives endothelial MR expression, which demonstrates a novel sex-specific mechanism explaining heightened endothelial MR activation in females.

Our current understanding of the regulation of endothelial MR transcription is limited. Castern et al demonstrated that neuronal MR transcription is increased by progesterone in rats, suggesting that endothelial MR may be one of several cell types that express progesterone-responsive transcription machinery that impacts MR expression 23. However, other studies have indicated that progesterone does not alter neuronal MR promoter activity in mice 24. Therefore, MR promoter activity and expression in response to progesterone receptor (PrR) activation may vary across species and tissue types, a hypothesis that has been previously postulated 25. Importantly, our data indicate that non-endothelial cells of the vasculature do not exhibit sex-differences in MR expression nor responsiveness to progesterone. Therefore, endothelial cells appear to be the most prominent cell type exhibiting PrR responsiveness and sex-specific MR expression.

Other investigators have shown that estrogen downregulates the genomic actions of MR in embryonic kidney and endothelial cells in the presence of aldosterone 26. Our data did not indicate a significant inhibition of MR mRNA in response to estrogen. However, in the presence of estrogen, progesterone did not restore endothelial MR expression in our ovariectomized female mice. The variability between these two studies may be explained by differences between an in vivo and in vitro system, in which aldosterone and estrogen levels are more tightly controlled. The effects of estrogen of MR transcriptional activity may therefore, warrant further investigation.

We demonstrate that administration of progesterone in vitro to human endothelial cells increases MR protein expression in an isolated cell environment and also in vivo that endothelial-specific PrR-deficiency (ECPrR−/−) in mice decreases endothelial MR expression. These data indicate that endothelial-specific PrR activation directly leads to increased endothelial MR expression in females and likely does not involve activation of PrR in peripheral tissues. Currently available data indicates that both classes of PrR’s are expressed in endothelial cells, the classical nuclear PrR and the membrane G-protein coupled receptor PrR 27, 28. Several findings in this study indicate that nuclear PrR are the most likely candidate receptor mediating progesterone-induced MR transcription. Firstly, we demonstrate that Ulipristal, a PrR-specific antagonist, decreases endothelial MR expression in female mice. Ulipristal, as opposed to other less specific progesterone receptor antagonists such as mifepristone, is believed to largely act at the nuclear receptor and does not bind MR, glucocorticoid or estrogen receptors 29, 30. However, it is important to note that data confirming the selectivity of Ulipristal is limited at present due to its novelty in the pharmaceutical market. The endothelial PrR knockout (ECPrR−/−) mice utilized for our study are derived from the introduction of Loxp sites in the nuclear PrR. Therefore, expression of the membrane PrR is unlikely to be altered in the endothelial cells of these mice as it is a distinct gene from that of the nuclear PrR 31. Therefore, suppression of endothelial MR in these mice indicates that nuclear PrR activation in endothelial cells stimulates endothelial MR transcription, however, whether this is a direct relationship or involves intracellular mediators is currently unknown and warrants further study.

Our data that fluctuating progesterone levels in estrous cycle and pregnancy present correlative changes in endothelial MR expression is of particular importance for speculation of the evolutionary importance of the progesterone-endothelial MR relationship. In healthy pregnancy, in which both circulating progesterone levels and endothelial MR expression are elevated, various physiological changes contribute to a systemic high-capacitance, low-resistance vascular system that is less sensitive to vasoconstrictive hormones 32, 33. However, aldosterone levels are dissociated from plasma renin activity in pregnant women and are also more sensitive to changes in posture and sodium intake compared to non-pregnant women 34. Although pressor sensitivity to aldosterone in pregnant vs non-pregnant women has not been investigated, we postulate that the aldosterone-endothelial MR signaling pathway is a mechanism that can acutely alter vasodilatory responses in response to changes in blood pressure in pregnancy, a crucial requirement to preserve feto-placental blood flow.

Recent clinical data reveals that vascular endothelial impairment is a crucial player in the pathogenesis of obesity-associated cardiovascular diseases in females. Endothelial cells are the primary vascular cell type sensing flow, regulating vascular tone, inflammation and cell proliferation. Therefore, endothelial dysfunction is a critical early event that predisposes to hypertension and cardiovascular events 12, 13, 35–37. Females are predisposed to the early development of obesity-associated endothelial dysfunction as compared to males 10, 11, suggesting that the vascular endothelium of females is more sensitive to obesity-associated mechanisms that impair function. We show that obesity in Agouti female mice is associated with a further upregulation of endothelial MR compared to male obese Agouti mice. Therefore, the physiological impact of endothelial MR on endothelial function in the context of obesity may be potentiated in females compared both to males and to lean females via upregulated endothelial MR activation.

We have previously shown that leptin stimulates the production of aldosterone in obese females 9 and that increased leptin in obese mice leads to a significant elevation in circulating aldosterone 9, a finding that correlates with clinical observations in obese women 38. In addition, leptin-induced aldosterone is a crucial mediator of endothelial dysfunction in obese female mice, as shown by the ability of leptin receptor inhibition or MR signaling to reverse endothelial impairment 10. In this report, we demonstrate that knockout of the endothelial MR prevents leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in female mice, while having the opposite effect in male mice. In addition, we show for the first time that MR expression in endothelial cells is increased by obesity in female mice. These findings, which build upon other published data 19, 20, indicate that activity of the endothelial MR, specifically, may underlie leptin-induced, aldosterone-mediated endothelial dysfunction in obese females.

The well documented observation that cardiovascular disease risk becomes more pronounced in women following menopause 39, 40 may appear at odds with the current study as protection from cardiovascular risk, notably from hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke, in premenopausal women stems from the cardioprotective benefits of female sex hormones, notably estrogens 39–42. This notion is supported by experimental evidence demonstrating that ovariectomy increases blood pressure and cardiomyopathy in lean and obese rodent models 43–45. Our data do suggest that progesterone promotes endothelial dysfunction via upregulation of the endothelial MR, however, these data do not imply that high progesterone levels can stimulate endothelial dysfunction per se without the combination of a pathological stressor i.e. obesity. This is particularly evident by our data that the endothelial MR is increased by pregnancy in mice. Healthy pregnancy is not characterized by endothelial dysfunction 46. Therefore it is likely that well-documented vasodilatory mechanisms in pregnant women protect from endothelial MR-mediated endothelial dysfunction in the absence of other pathological mechanisms 47. In addition, progesterone can function as a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist at high concentrations, and as levels of progesterone in pregnancy are highly elevated, it may be postulated that high levels of progesterone antagonizes endothelial MR activation and is protective in this context 48. Our data do indicate, however, that obesity in pregnancy, which is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including endothelial dysfunction, may involve activation of the endothelial MR 49, 50. The underlying mechanism for obesity-induced activation of endothelial MR in pregnancy is likely derived from increased leptin-induced aldosterone in obese pregnant women, which then outcompetes progesterone in binding to and activating the highly upregulated MR in endothelial cells of the vasculature, an important potential mechanism that warrants future studies.

A limitation of our data is that measurement of endothelial MR expression in our mouse models was restricted to only mRNA and not protein expression. Unfortunately, antibodies for the MR are notoriously limited by sensitivity and specificity in murine tissues, and the very limited amount of protein from aortic and renal endothelial cells did not yield acceptable results with Western blotting. Therefore, we confirmed whether MR mRNA expression data mirrors protein expression by supplementing human umbilical endothelial cells with progesterone in culture, which confirmed a dose-dependent increase in MR protein expression. In addition, we were able to obtain a small N (3) of human endothelial cells samples from young human patients for MR protein expression measurement, which further confirmed a sex-specific upregulation in human endothelial cells from female patients compared to males. The N number of this study is admittedly lower than desired, however, clinical difficulty in obtaining aorta endothelial cells in sufficient quantities from young patients precluded us from obtaining a higher N.

In summary, our data indicate: 1. that endothelial MR expression is endogenously elevated in females compared to males, which is exacerbated by obesity in female mice, 2. that endothelial PrR expression increases endothelial MR expression and 3. that both intact MR and PrR expression are required for leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in female mice. These data are in line with previous studies that indicate that endothelial MR deletion protects female mice from obesity-associated endothelial dysfunction and vascular stiffness and demonstrate for the first time an endothelial cell-level sex difference that is likely the major player in these sex differences in obesity-associated vascular phenotypes between male and female mice.

Perspectives

Collectively, data from this study provides novel mechanistic insight into sex-specific mechanisms of obesity induced vascular dysfunction and indicates that therapeutics targeting the MR may offer superior clinical efficacy in improving the health of obese women at risk for cardiovascular disorders. The most efficacious MR antagonist for the treatment of obesity-associated cardiovascular disorders in females remains to be determined, as the affinity of MR antagonists for MR differs between the currently clinically available forms, spironolactone, eplerenone and finerenone51. Spironolactone, being a less specific MR antagonist than eplerenone or finerenone, also has some affinity to antagonize the PrR, indicating spironolactone may be a more efficacious agent. The selectivity of MR antagonists and how this affects their ability to improve endothelial function in premenopausal obese women warrants further study.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is new?

Endothelial MR expression is endogenously elevated in females compared to males, which is exacerbated by obesity in female mice

Endothelial PrR expression increases endothelial MR expression

Intact MR and PrR expression are required for leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in female mice

What is relevant?

Progesterone drives sex-differences in obesity-associated endothelial dysfunction via upregulating endothelial MR expression

Inhibition of endothelial MR activation, via MR antagonists, may be a crucial therapeutic target for hypertension in obese women

Summary.

Female mice and humans endogenously express higher levels of endothelial MR expression compared to males, which is driven by endothelial progesterone receptor expression. The progesterone and mineralocorticoid receptors in endothelial cells mediate obesity-associated endothelial dysfunction in females.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Celso and Elise Gomez Sanchez at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson MS for generously providing western blotting antibodies for mineralocorticoid receptor. We would additionally like to thank Dr. DeMayo, NIH/NIEHS for providing the progesterone receptor floxed mice and Dr. Adams, Max-Planck-Institute for Molecular Medicine for providing the endothelial-specific Cdh5-CreERT2 mice.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH 1R01HL130301–01 and AHA 16IRG27770047 to EbdC and AHA 17POST33660678 and NIH 5F32HL136191–02 to JLF and NIH R01 HL095590 to IZJ.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Khan SS, Ning H, Wilkins JT, Allen N, Carnethon M, Berry JD, Sweis RN, Lloyd-Jones DM. Association of body mass index with lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease and compression of morbidity. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:280–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nabel EG. Heart disease prevention in young women: Sounding an alarm. Circulation. 2015;132:989–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grassi G, Dell’Oro R, Facchini A, Quarti Trevano F, Bolla GB, Mancia G. Effect of central and peripheral body fat distribution on sympathetic and baroreflex function in obese normotensives. J Hypertens. 2004;22:2363–2369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall JE, da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Dubinion J, Hamza S, Munusamy S, Smith G, Stec DE. Obesity-induced hypertension: Role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin, and melanocortins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17271–17276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert E, Straznicky N, Eikelis N, Esler M, Dawood T, Masuo K, Schlaich M, Lambert G. Gender differences in sympathetic nervous activity: Influence of body mass and blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1411–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straznicky NE, Grima MT, Eikelis N, Nestel PJ, Dawood T, Schlaich MP, Chopra R, Masuo K, Esler MD, Sari CI, Lambert GW, Lambert EA. The effects of weight loss versus weight loss maintenance on sympathetic nervous system activity and metabolic syndrome components. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tank J, Heusser K, Diedrich A, Hering D, Luft FC, Busjahn A, Narkiewicz K, Jordan J. Influences of gender on the interaction between sympathetic nerve traffic and central adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4974–4978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks VL, Shi Z, Holwerda SW, Fadel PJ. Obesity-induced increases in sympathetic nerve activity: Sex matters. Auton Neurosci. 2015;187:18–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huby AC, Antonova G, Groenendyk J, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Bollag WB, Filosa JA, Belin de Chantemele EJ. Adipocyte-derived hormone leptin is a direct regulator of aldosterone secretion, which promotes endothelial dysfunction and cardiac fibrosis. Circulation. 2015;132:2134–2145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huby AC, Otvos L Jr., Belin de Chantemele EJ. Leptin induces hypertension and endothelial dysfunction via aldosterone-dependent mechanisms in obese female mice. Hypertension. 2016;67:1020–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suboc TM, Dharmashankar K, Wang J, Ying R, Couillard A, Tanner MJ, Widlansky ME. Moderate obesity and endothelial dysfunction in humans: Influence of gender and systemic inflammation. Physiol Rep. 2013;1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deanfield JE, Halcox JP, Rabelink TJ. Endothelial function and dysfunction: Testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2007;115:1285–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suwaidi JA, Hamasaki S, Higano ST, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR Jr. Lerman A Long-term follow-up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2000;101:948–954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safar ME, Balkau B, Lange C, Protogerou AD, Czernichow S, Blacher J, Levy BI, Smulyan H. Hypertension and vascular dynamics in men and women with metabolic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:12–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanashiro-Takeuchi RM, Heidecker B, Lamirault G, Dharamsi JW, Hare JM. Sex-specific impact of aldosterone receptor antagonism on ventricular remodeling and gene expression after myocardial infarction. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2:134–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khosla N, Kalaitzidis R, Bakris GL. Predictors of hyperkalemia risk following hypertension control with aldosterone blockade. Am J Nephrol. 2009;30:418–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bostick B, Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Jia G, Domeier TL, Lambert MD, Aroor AR, Nistala R, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Ma L, Manrique C, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents western diet-induced diastolic dysfunction in female mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H1126–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeMarco VG, Habibi J, Jia G, Aroor AR, Ramirez-Perez FI, Martinez-Lemus LA, Bender SB, Garro M, Hayden MR, Sun Z, Meininger GA, Manrique C, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Low-dose mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents western diet-induced arterial stiffening in female mice. Hypertension. 2015;66:99–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davel AP, Lu Q, Moss ME, Rao S, Anwar IJ, DuPont JJ, Jaffe IZ. Sex-specific mechanisms of resistance vessel endothelial dysfunction induced by cardiometabolic risk factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia G, Habibi J, Aroor AR, Martinez-Lemus LA, DeMarco VG, Ramirez-Perez FI, Sun Z, Hayden MR, Meininger GA, Mueller KB, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor mediates diet-induced aortic stiffness in females. Circ Res. 2016;118:935–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu X, Gangisetty O, Carver CM, Reddy DS. Estrous cycle regulation of extrasynaptic delta-containing gaba(a) receptor-mediated tonic inhibition and limbic epileptogenesis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346:146–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Garcia C, Lopez-Contreras AJ, Cremades A, Castells MT, Marin F, Schreiber F, Penafiel R. Molecular and morphological changes in placenta and embryo development associated with the inhibition of polyamine synthesis during midpregnancy in mice. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5012–5023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castren M, Patchev VK, Almeida OF, Holsboer F, Trapp T, Castren E. Regulation of rat mineralocorticoid receptor expression in neurons by progesterone. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3800–3806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munier M, Meduri G, Viengchareun S, Leclerc P, Le Menuet D, Lombes M. Regulation of mineralocorticoid receptor expression during neuronal differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2244–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zennaro MC, Le Menuet D, Lombes M. Characterization of the human mineralocorticoid receptor gene 5’-regulatory region: Evidence for differential hormonal regulation of two alternative promoters via nonclassical mechanisms. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1549–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrett Mueller K, Lu Q, Mohammad NN, Luu V, McCurley A, Williams GH, Adler GK, Karas RH, Jaffe IZ. Estrogen receptor inhibits mineralocorticoid receptor transcriptional regulatory function. Endocrinology. 2014;155:4461–4472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang Y, Dong J, Thomas P. Progesterone increases nitric oxide synthesis in human vascular endothelial cells through activation of membrane progesterone receptor-alpha. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308:E899–911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vazquez F, Rodriguez-Manzaneque JC, Lydon JP, Edwards DP, O’Malley BW, Iruela-Arispe ML. Progesterone regulates proliferation of endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2185–2192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cadepond F, Ulmann A, Baulieu EE. Ru486 (mifepristone): Mechanisms of action and clinical uses. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:129–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richardson AR, Maltz FN. Ulipristal acetate: Review of the efficacy and safety of a newly approved agent for emergency contraception. Clin Ther. 2012;34:24–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandez-Valdivia R, Jeong J, Mukherjee A, Soyal SM, Li J, Ying Y, Demayo FJ, Lydon JP. A mouse model to dissect progesterone signaling in the female reproductive tract and mammary gland. Genesis. 2010;48:106–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdul-Karim R, Assalin S. Pressor response to angiotonin in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;82:246–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbert JS, Ryan MJ, LaMarca BB, Sedeek M, Murphy SR, Granger JP. Pathophysiology of hypertension during preeclampsia: Linking placental ischemia with endothelial dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H541–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bentley-Lewis R, Graves SW, Seely EW. The renin-aldosterone response to stimulation and suppression during normal pregnancy. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2005;24:1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caniffi C, Cerniello FM, Gobetto MN, Sueiro ML, Costa MA, Arranz C. Vascular tone regulation induced by c-type natriuretic peptide: Differences in endothelium-dependent and -independent mechanisms involved in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0167817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Villar IC, Francis S, Webb A, Hobbs AJ, Ahluwalia A. Novel aspects of endothelium-dependent regulation of vascular tone. Kidney Int. 2006;70:840–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao K, Tschudi M, Flammer J, Luscher TF. Endothelium-dependent regulation of vascular tone of the porcine ophthalmic artery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:1791–1798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodfriend TL, Kelley DE, Goodpaster BH, Winters SJ. Visceral obesity and insulin resistance are associated with plasma aldosterone levels in women. Obes Res. 1999;7:355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, Horan MJ, Labarthe D. Prevalence of hypertension in the us adult population. Results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lima R, Wofford M, Reckelhoff JF. Hypertension in postmenopausal women. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2012;14:254–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bairey Merz CN, Johnson BD, Sharaf BL, Bittner V, Berga SL, Braunstein GD, Hodgson TK, Matthews KA, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Reichek N, Rogers WJ, Pohost GM, Kelsey SF, Sopko G, Group WS. Hypoestrogenemia of hypothalamic origin and coronary artery disease in premenopausal women: A report from the nhlbi-sponsored wise study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ossewaarde ME, Bots ML, Verbeek AL, Peeters PH, van der Graaf Y, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Age at menopause, cause-specific mortality and total life expectancy. Epidemiology. 2005;16:556–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupte M, Thatcher SE, Boustany-Kari CM, Shoemaker R, Yiannikouris F, Zhang X, Karounos M, Cassis LA. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 contributes to sex differences in the development of obesity hypertension in c57bl/6 mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1392–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hinojosa-Laborde C, Lange DL, Haywood JR. Role of female sex hormones in the development and reversal of dahl hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jia C, Chen H, Wei M, Chen X, Zhang Y, Cao L, Yuan P, Wang F, Yang G, Ma J. Gold nanoparticle-based mir155 antagonist macrophage delivery restores the cardiac function in ovariectomized diabetic mouse model. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:4963–4979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopes van Balen VA, van Gansewinkel TAG, de Haas S, van Kuijk SMJ, van Drongelen J, Ghossein-Doha C, Spaanderman MEA. Physiological adaptation of endothelial function to pregnancy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tkachenko O, Shchekochikhin D, Schrier RW. Hormones and hemodynamics in pregnancy. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;12:e14098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Funder JW. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists: Emerging roles in cardiovascular medicine. Integr Blood Press Control. 2013;6:129–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Markovic N, Roberts JM. The risk of preeclampsia rises with increasing prepregnancy body mass index. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: Systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ. 2005;330:565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pei H, Wang W, Zhao D, Wang L, Su GH, Zhao Z. The use of a novel non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone for the treatment of chronic heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.