Abstract

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) appears to be a promising intervention for the prevention of relapse in major depressive disorder, but its efficacy in patients with current depressive symptoms is less clear. Randomized clinical trials of MBCT for adult patients with current depressive symptoms were included (k = 13, N = 1,046). Comparison conditions were coded based on whether they were intended to be therapeutic (specific active controls) or not (non-specific controls). MBCT was superior to non-specific controls at post-treatment (k = 10, d = 0.71, 95% CI [0.47, 0.96]), although not at longest follow-up (k = 2, d = 1.47, [−0.71, 3.65], mean follow-up = 5.70 months across all studies with follow-up). MBCT did not differ from other active therapies at post-treatment (k = 6, d = 0.002, [−0.43, 0.44]) and longest follow-up (k = 4, d = 0.26, [−0.24, 0.75]). There was some evidence that studies with higher methodological quality showed smaller effects at post-treatment, but no evidence that effects varied by inclusion criterion. The impact of publication bias appeared minimal. MBCT seems to be efficacious for samples with current depressive symptoms at post-treatment, although a limited number of studies tested the long-term effects of this therapy.

Keywords: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, depression, meta-analysis, relative efficacy

Of all mental health conditions, depression is one of the most common and is responsible for significant public health costs (Collins et al., 2011). A variety of evidence-based psychosocial interventions have been developed to treat the disease burden of depressive disorders (Cuijpers, van Straten, Andersson, & van Oppen, 2008). One such treatment with growing scientific, clinical, and popular interest is mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002). MBCT was developed to function as prophylaxis against the relapsing course typical in major depressive disorder (MDD; Teasdale et al., 2000). The developers of MBCT posited that patients with a history of depression who were currently in remission could successfully learn cognitive and affective strategies that would better equip them for managing the patterns of thinking activated by dysphoria that unavoidably occurs in daily life that is magnified in the context of MDD. By learning these skills while in remission, patients could prevent the intensification of depressogenic patterns of cognition (e.g., rumination) that lead to relapse (Segal & Dinh-Williams, 2016; Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995). Indeed, the initial formulation of MBCT highlighted the treatment being “acceptable in the euthymic state” (p. 38) and focused on preventing “the escalation of states of mild negative affect to more severe and persistent states” (p. 36; Teasdale et al., 1995). That is to say, the treatment was not initially intended for currently depressed patients whose degree of negative affect was more severe.

A number of clinical trials have evaluated MBCT for the prevention of depressive relapse and several meta-analyses have supported the efficacy of MBCT for this purpose (Kuyken et al., 2016; Piet & Hougaard, 2011). A recent meta-analysis also included individual patients’ data that allowed a fine-grained analysis of potential moderators of treatment effects. Kuyken and colleagues (2016) report benefits associated with MBCT relative to those who did not receive MBCT, with reductions in the risk of depressive relapse within a 60-week follow-up period (hazard ratio = 0.69, 95% CI [0.58, 0.82]). They also found that MBCT appeared particularly effective for patients with higher baseline residual symptoms. This is an important finding in that it can inform for whom MBCT may be most effective. While intriguing, the study sample was limited by including only studies conducted with patients in remission; it therefore leaves open the question of whether MBCT may benefit individuals with ongoing depression.

There has been a substantial increase in the number of studies published in the past several years examining the efficacy of MBCT among people who are currently experiencing depression or elevated symptoms of depression (see Table 1). While several meta-analyses have indicated that mindfulness-based interventions in general – including MBCT, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and others – are effective at reducing depressive symptoms (see Goldberg et al., 2018; Goyal et al., 2014; Hedman-Lagerlöf, Hedman-Lagerlöf, & Öst, 2018; Khoury et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2018), to our knowledge no meta-analysis to date has examined the efficacy of MBCT specifically for patients with current depressive symptoms. However, such a meta-analysis is vital for establishing the efficacy of MBCT for this population (American Psychological Association, 2006). Given increasing efforts towards dissemination and implementation of MBCT (e.g., within the United Kingdom based on National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE] [2009] guidelines; Crane & Kuyken, 2013), evaluation of the evidence for MBCT among individuals with current depressive symptoms may also have health service implications.

Table 1.

Study-level descriptive statistics

| Original Study | Control Group | Control Type | Inclusion | ES | Var | ES FU | Var FU | Tx n | Cont n | Age | % Fem |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abolghasemi 2015 | CT | Spec | Dep dx | 0.61 | 1.87 | 1.06 | 1.68 | 15 | 15 | 29.00 | 60.00 |

| Asl 2014 | Waitlist | Non | Elevated sx | 0.81 | 0.14 | NA | NA | 18 | 17 | 29.50 | 0.00 |

| Chiesa 2015 | Psychoed | Spec | Elevated sx | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.09 | 26 | 24 | 48.95 | 72.09 |

| Cladder-Micus 2018 | Waitlist | Non | Dep dx | 0.38 | 0.04 | NA | NA | 49 | 57 | 47.10 | 62.26 |

| DeJong 2016 | Waitlist | Non | Elevated sx | 0.18 | 0.09 | NA | NA | 26 | 14 | 50.70 | 72.70 |

| Eisendrath 2016 | HEP | Spec | Dep dx | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 87 | 86 | 46.16 | 76.30 |

| Kaviani 2012 | Waitlist | Non | Elevated sx | 0.56 | 0.20 | 2.66 | 0.43 | 15 | 15 | 21.70 | 100.00 |

| Leung 2015 | Waitlist | Non | Elevated sx | 1.07 | 0.08 | NA | NA | 31 | 56 | 44.68 | 77.80 |

| Michalak 2015 | TAU | Non | Dep dx | 0.43 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 36 | 35 | 50.84 | 62.26 |

| Michalak 2015 | CBASP | Spec | Dep dx | −0.34 | 0.07 | −0.11 | 0.10 | 36 | 35 | 50.84 | 62.26 |

| Omidi 2013 | Waitlist | Non | Dep dx | 1.40 | 0.11 | NA | NA | 30 | 30 | 28.00 | 66.33 |

| Omidi 2013 | CBT | Spec | Dep dx | −0.85 | 0.21 | NA | NA | 30 | 30 | 28.00 | 66.33 |

| Panahi 2016 | Waitlist | Non | Elevated sx | 1.30 | 0.09 | NA | NA | 30 | 30 | NA | 100.00 |

| Tovote 2014 | Waitlist | Non | Elevated sx | 0.74 | 0.06 | NA | NA | 31 | 31 | 53.10 | 49.00 |

| Tovote 2014 | CBT | Spec | Elevated sx | −0.19 | 0.07 | NA | NA | 31 | 32 | 53.10 | 49.00 |

| VanAalderen 2012 | TAU | Non | Elevated sx | 0.57 | 0.05 | NA | NA | 74 | 72 | 47.50 | 71.00 |

Note: Inclusion = study depression inclusion criterion (Dep dx = diagnosis of depression, Elevated sx = symptoms above clinical cut-off on standardized measure of depression); ES = standardized effect size in Cohen’s d units; Var = variance; FU = longest follow-up; Tx n = mindfulness condition sample size; Cont n = control condition sample size; Non = non-specific control condition (i.e., not intended to be therapeutic); Spec = specific active control condition (i.e., intended to be therapeutic; Wampold & Imel, 2015); Age = average sample age; % Fem = percentage female; NA = not applicable; CT = cognitive therapy; TAU = treatment-as-usual; HEP = Health Enhancement Program; Psychoed = psychoeducation; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; CBASP = Cognitive Behavioral Analysis System of Psychotherapy.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We included RCTs of MBCT for adult patients with current depressive symptoms defined either via diagnostic interview (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis [SCID]) or scores above the clinical cut-off on a standardized, clinician-rated or self-report measure of depressive symptoms (e.g., Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]; Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression [HAM-D]). To be included, a trial had to specify that the mindfulness intervention offered was MBCT based on the work of Segal et al. (2002). Interventions had to be delivered in real time (i.e., provided synchronously, not simply through pre-recorded video instruction). Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) data unavailable to compute standardized effect sizes (even after contacting study authors); (2) no depression outcomes (e.g., BDI, HAM-D) reported; (3) data redundant with other included studies; (4) no non-mindfulness-based intervention or condition included (e.g., study compared two mindfulness-based interventions).

Information Sources

We searched the following databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science. In addition, a publicly available comprehensive repository of mindfulness studies that is updated monthly was also searched (Black, 2012). Citations from recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews were also included (Goyal et al., 2014; Khoury et al., 2013; Kuyken et al., 2016). An initial search of citations included those from the first available date until January 2nd, 2017. In addition, we searched for unpublished trials by reviewing studies registered in clinicaltrials.gov. The search was subsequently updated on October 5th, 2018.

Search

The initial search was part of a larger, comprehensive meta-analysis examining the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions for a range of psychiatric conditions (Goldberg et al., 2018). In contrast to the larger meta-analysis, which included eleven diagnostic categories (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, sleep disorders) and various mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based stress reduction [MBSR], mindfulness-based relapse prevention [MBRP]; Bowen et al., 2014; Kabat-Zinn, 1990), the current study focuses exclusively on the evidence for MBCT in samples with current depressive symptoms. For the initial search, the terms “mindfulness” and “random*” were used, with studies relevant to depression drawn from the larger sample. Dissertations and studies published in non-peer-reviewed journals were also included in the search. Clinicaltrials.gov was searched using the terms “depression” and “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.” For the updated search, we used the terms “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy” or “MBCT” paired with “random*.”

Study Selection

Titles and/or abstracts of potential studies were independently coded by the first author and a second co-author. Disagreements were discussed with the senior author.

Data Collection Process

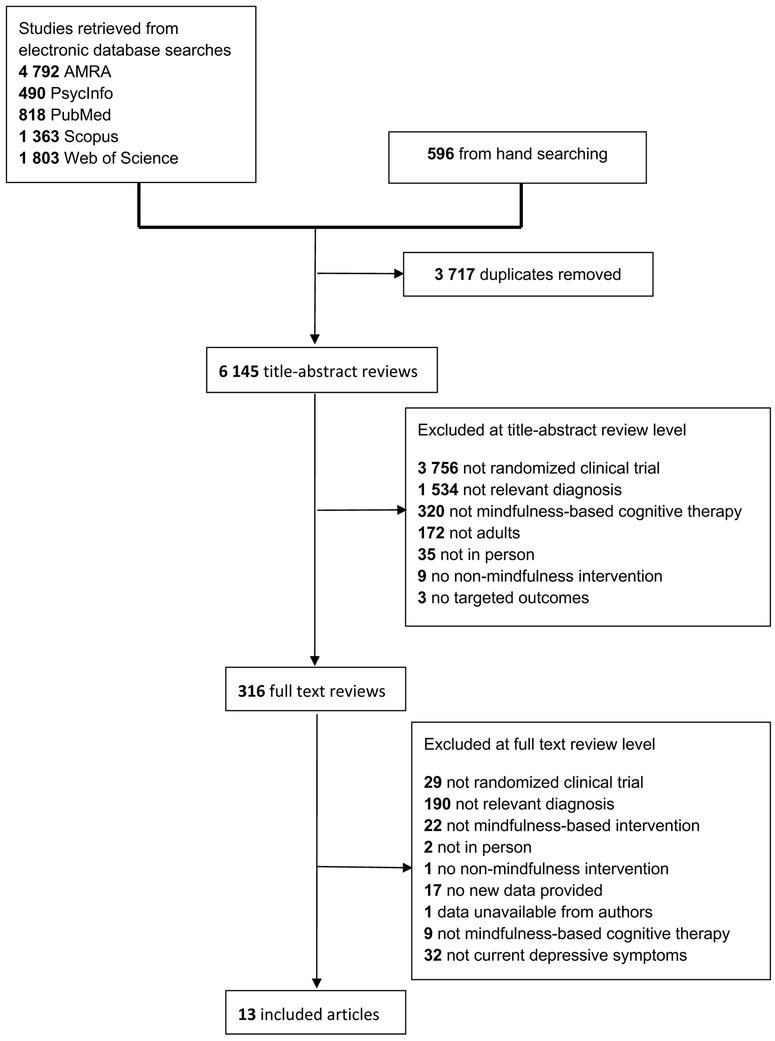

Standardized spreadsheets were developed for coding both study-level and effect size-level data. Coders were trained by the first author through coding an initial sample of studies (k = 10) in order to achieve reliability. Data were extracted independently by the first author and a second co-author. Disagreements were discussed with the senior author. Inter-rater reliabilities were in the good to excellent range (Cicchetti, 1994): Ks > .60 and ICCs > 0.80. When sufficient data for computing standardized effect sizes were unavailable, study authors were contacted. One study was excluded due to data being unavailable from study authors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data Items

Along with data necessary for computing standardized effect sizes, the following data were extracted: (1) publication year; (2) intent-to-treat (ITT) sample size; (3) sample demographics1 (mean age, percentage female); (4) country of origin; (5) quality of the control condition. Quality of the control condition was assessed based on a two-tier system: non-specific control conditions and specific active control conditions. Non-specific control conditions included waitlist controls as well as other comparison groups that were not intended to provide therapeutic benefits (e.g., attentional control groups). Treatment-as-usual (TAU) conditions were coded as non-specific controls if both the MBCT and non-MBCT arms received this treatment (i.e., there was no additional treatment provided to the TAU group that was not also provided to the MBCT group). The specific active control conditions (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) included comparisons that were based on actual therapies (i.e., not “placebo” conditions that were not intended to be therapeutic) and included specific treatment ingredients and mechanisms of change (Wampold & Imel, 2015; Wampold et al., 1997). The decision to code using this scheme was made to minimize the number of comparisons being tested, to increase the number of studies (and statistical power) available for a given comparison, and based on evidence that whether a comparison group represents a specific active control condition significantly influences the relative efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (Goldberg et al., 2018; Goyal et al., 2014). The comparison with other active therapies has been consistently highlighted as a key test of the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015; Goldberg et al., 2017).

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Considerations for minimizing bias and assessing methodological quality in individual studies were modeled after a previous meta-analysis of MBCT for depressive relapse (Piet & Hougaard, 2011). We used Piet and Hougaard’s (2011) modified Jadad (1996) criteria, coding (a) whether a trial was randomized, (b) whether the randomization procedure was described and appropriate (e.g., employed randomly generated group assignment), (c) whether outcome assessment was blind to group assignment, and (d) whether reasons were given for the withdrawal and dropouts in each group. Items were coded as “yes” if the criterion was present, “no” if not present, and “unclear” if the presence of this feature was ambiguous. To compute a Jadad score, we summed all four items, coding yes responses as 1 and no or unclear responses as 0. In order to assess the impact of these features on study results, Jadad scores were tested as moderators of treatment effects in primary analyses.

Five additional items were also coded based on Piet and Hougaard (2011). While these items did not contribute to the Jadad score, they provide information regarding the studies’ risk for bias and methodological quality. Namely, we also assessed (a) whether treatment allocation was concealed (e.g., using an opaque envelope or an external allocator to provide group assignments), (b) whether groups were similar at baseline on prognostic indicators, (c) whether the number of withdrawals and dropouts in each group were mentioned, (d) whether analyses were conducted using the intent-to-treat (ITT) sample, and (e) whether a power calculation was described. As before, these items were coded as yes, no, or unclear.

We considered using other methods for assessing risk for bias (e.g., Cochrane tool, GRADE; Atkins et al., 2003; Higgins & Green, 2011). Ultimately, we felt that providing information about specific study features and reporting the uncertainty of effect size estimates (using confidence intervals and metrics of heterogeneity, i.e., I2) was preferable to making at least partially subjective judgments about the strength of the body of evidence. Further, providing ratings consistent with previous meta-analyses of MBCT seemed ideal for allowing comparison between these related bodies of research. In addition, to reduce potential bias, we used data from ITT analyses when available.

Summary Measures

Our primary effect size measure was the standardized mean difference (Cohen’s d). As done by Goyal et al. (2014) and Goldberg et al. (2018), we first computed a pre-post (or pre-follow-up) effect size for both the MBCT and control groups alone. This method has the advantage of accounting for potential baseline differences (i.e., it does not rely exclusively on between-group differences at post-test; Becker, 1988). Formulas for these within-group effect sizes and their variance are as follows:

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

where r is the correlation between pre- and post-scores. As is often the case, the included studies did not report r, so we imputed a correlation of rXX = .50 between time points (slightly lower than a typical test-retest correlation, to account for intervention effects; see Hoyt & Del Re, 2017). Within-group effect sizes were corrected for bias by converting to Hedges’ gwithin as recommended by Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, and Rothstein (2009). Effects were computed both from pre- to post-treatment (or time point closest to post-treatment) as well as from pre- to last available follow-up time point.

We then calculated the relative difference in the pre-post (or pre-follow-up) effects (i.e., change scores) between the MBCT and control conditions using standard methods (Becker, 1988).

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

where the M and C superscripts refer to the MBCT and comparison conditions, respectively. Given the resultant effect size remains within standard deviation units, we have retained the notation of the more familiar d (rather than Becker’s Δ) to refer to treatment effects.

Analyses were conducted using the R statistical software and the ‘metafor’ and ‘MAd’ packages (Del Re & Hoyt, 2010; Viechtbauer, 2010).

Synthesis of Results

When available, effect sizes were computed using pre- and post-test means and standard deviations (SD). Other reported statistics (e.g., F, t, p, odds ratios) were used when appropriate based on standard meta-analytic methods (Cooper et al., 2009). When multiple measures of depression were reported (e.g., relapse rates based on clinical interview, scores on self-report measures of depression), data were aggregated first within-studies using the ‘MAd’ package (and an assumed correlation between measures of .50, see Wampold et al., 1997 for a rationale) and then between studies, based on the comparison of interest (i.e., MBCT vs. non-specific control conditions). Summary statistics were computed in standardized units along with 95% confidence intervals. Heterogeneity was systematically assessed using the I2 (measuring the proportion of between-study heterogeneity) and interpreted based on Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, and Altman’s (2003) guidelines. Random effects analyses were used with effect sizes weighted by the inverse of their variance (Cooper et al., 2009). Models were run separately for the specific active comparison conditions and the non-specific comparison conditions. In addition, we conducted analyses to assess the potential impact of variation in inclusion criterion related to depressive symptoms across the sample. Specifically, we conducted moderator analyses to assess whether effects differed for studies that required a formal diagnosis of depression (e.g., MDD diagnoses via SCID; Michalak, Schultze, Heidenreich, & Schramm, 2015) versus those that required only symptoms above a clinical cut-off (e.g., on the BDI-II; Tovote et al., 2014). Results are reported separately based on diagnostic inclusion criterion.

Three studies (Omidi, Mohammadkhani, Mohammadi, & Zargar, 2013; Michalak et al., 2015; Tovote et al., 2014) included both a specific active comparison group and a non-specific control group (i.e., waitlist). Given specific active comparisons and non-specific control groups were assessed in separate models, in order to more fully represent the available data we allowed multiple comparison groups to be included from these three studies. This required duplicating data from each study’s MBCT condition to make the additional comparison. To assess potential bias introduced by duplicating MBCT condition data (Higgins & Green, 2011), we report sensitivity analyses where the comparisons with non-specific control conditions for these three studies are excluded.

Risk of Bias Across Studies

We assessed publication bias by visually inspecting funnel plots for asymmetry within the comparison of interest. In addition, models were re-estimated using trim-and-fill methods that account for the asymmetric distribution of studies around an omnibus effect (Viechtbauer, 2010). Meta-regression models were also run modeling indicators of study quality using the modified Jadad score (Piet & Hougaard, 2011) as a moderator of treatment effects. A fail-safe N was computed based on Rosenthal’s (1979) method in order to estimate the number of unpublished null finding studies that would need to exist to nullify the observed effect in the current sample of studies.

Results

Study Selection

A total of 9,862 citations were retrieved. After 3,717 duplicates were removed, 6,145 unique titles and/or abstracts were coded. Following the application of the exclusion criteria (see Figure 1 for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis [PRISMA] flow diagram, see Supplemental Materials for full PRISMA Checklist; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, and the PRISMA Group, 2009), 13 studies were retained for analysis representing 1,046 participants.

In addition, 61 trials were identified from clinicaltrials.gov. Three of these trials were among the 12 located through searching the published literature. The remaining 58 trials were excluded for the following reasons: trial not completed (k = 29), not relevant diagnosis (k = 16), not RCT (k = 6), not MBCT (k = 4), and no non-mindfulness condition (k = 3). One additional study (Cladder-Micus et al., 2018) was located during the course of updating the literature review.

Study Characteristics

The sample was on average 41.44 years old (SD = 11.02) and 66.90% female. The largest percentage of trials was conducted in the Iran (38.46%) followed by the Netherlands (23.08%) and the United States (15.38%). A minority of studies (k = 5, 38.46%) included a follow-up time point. Among studies with follow-up, the average length to follow-up was 5.70 months (SD = 2.96, range = 2 to 10).

Risk of Bias Within Studies

Table 2 presents scores on the four modified Jadad items along with five additional metrics of methodological quality and risk for bias. All included studies used randomized designs. Modified Jadad scores ranged from 1 to 4 with a mean rating of 2.46 (SD = 0.97), which is slightly lower than the mean of 3.00 reported by Piet and Hougaard (2011). Only one study (Eisendrath et al., 2016) received a score of 1 for all four Jadad items, although seven studies received a score of 3. Blind outcome assessment was conducted in 23.08% of studies and ITT analyses were reported in 46.15% of studies.

Table 2.

Methodological quality and modified Jadad scoring for included studies.

| Study | Was the trial randomized? | Was the randomization procedure described and appropriate? | Was the treatment allocation concealed? | Were groups similar at baseline on prognostic indicators? | Was blind outcome assessments conducted? | Was the number of withdrawals/dropouts in each group mentioned? | In addition to stating the number of withdrawals/drop outs, were reasons given for each group? | Was an analysis conducted on the intent-to-treat sample? | Was a power calculation described? | Jadad score (revised maximum = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abolghasemi 2015 | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | Unclear | No | 1 |

| Asl 2014 | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 |

| Chiesa 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Cladder-Micus 2018 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| DeJong 2016 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Eisendrath 2016 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 4 |

| Kaviani 2012 | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | Yes | No | No | No | 1 |

| Leung 2015 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| Michalak 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Omidi 2013 | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | No | No | No | Unclear | No | 1 |

| Panahi 2016 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | 2 |

| Tovote 2014 | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| VanAalderen 2012 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | No | 3 |

Note: Bolded columns used for computation of revised Jadad score (see Piet & Hougaard, 2011).

Results of Individual Studies

For each included study, treatment effects on depressive outcomes in standardized units and other study characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Synthesis of Results

Effects at post-treatment.

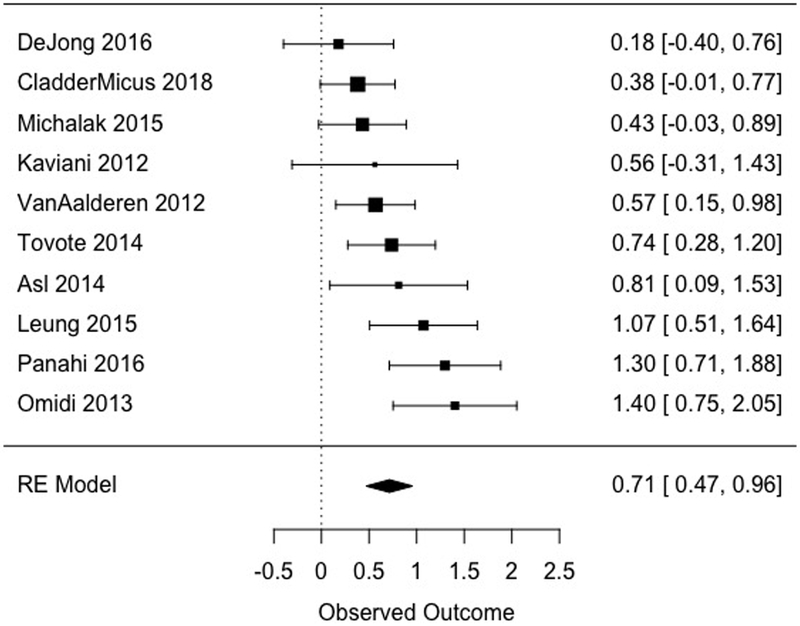

MBCT was shown to be superior to non-specific control conditions at post-treatment across ten studies (d = 0.71, [0.47, 0.96], Table 3, Figure 2), with a moderate amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 50.40). In a sensitivity analysis that excluded three non-specific control conditions in studies that included multiple comparison groups, effects were similar (k = 7, d = 0.68 [0.38, 0.97]). Effects were not moderated by inclusion criterion (i.e., diagnosis of depression vs. symptoms above a clinical cut-off on a standardized measure of depression), ds = 0.69 and 0.74, for diagnosis of depression and elevated symptoms, respectively, Q[1] = 0.10, p = .754.

Table 3.

Results of meta-analysis and trim-and-fill analysis

| Meta-analysis | Trim-and-fill analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time point | Comparison Type | N | k | ES [95% CI] | I2 [95% CI] | Fail-safe N | kimp | ESadj [95% CI] |

| Post | Non-specifica | 697 | 10 | 0.71 [0.47, 0.96] | 50.40 [0.00, 86.13] | 239 | 0 | |

| Post | Specificb | 447 | 6 | 0.002 [−0.43, 0.44] | 65.34 [3.22, 94.97] | 0 | 0 | |

| Follow-up | Non-specific | 101 | 2 | 1.47 [−0.71, 3.65] | 89.40 [46.75, 99.74] | 10 | NA | |

| Follow-up | Specific | 324 | 4 | 0.26 [−0.24, 0.75] | 59.31 [0.00, 97.72] | 1 | 1 | 0.23 [−0.24, 0.70] |

Note: N = sample size (note that total sample size is larger than the unique sample size due to some studies including multiple comparison groups); k = number of comparisons (note that total number of comparisons is larger than the unique sample size due to some studies including multiple comparison groups); ES = Cohen’s d standardized effect size; I2 = heterogeneity; kimp = number of imputed comparisons based on trim-and-fill analyses; ESadj = adjusted effect size based on trim-and-fill analyses; Dep diagnosis = studies requiring a diagnosis of depression for inclusion criterion; Elevated symptoms = studies requiring elevated symptoms of depression on a standardized measures of depression for inclusion criterion. Superscripts a and b report results of testing inclusion criterion as moderator of treatment effects.

Q[1] = 0.10, p = .754.

Q[1] = 0.32, p = .570.

Figure 2.

Effects of MBCT versus non-specific comparison conditions at post-treatment. The size of each point is relative to the given study’s weight in the meta-analysis (i.e. inverse variance).

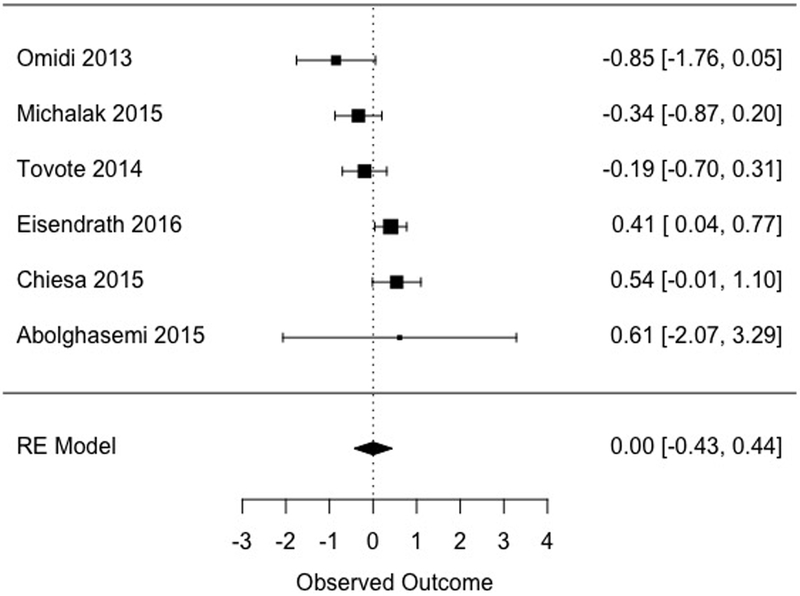

Across six studies, MBCT did not differ statistically from specific active control conditions at post-treatment (d = 0.002, [−0.43, 0.44], Figure 3). A moderate to large amount of heterogeneity was detected in this subsample (I2 = 65.34). Effects were again not moderated by inclusion criterion (ds = −0.13 and 0.17, for diagnosis of depression and elevated symptoms, respectively, Q[1] = 0.32, p = .570). As inclusion criterion did not appear to influence post-treatment effects for studies using either non-specific or specific active control conditions, subsequent analyses collapsed across samples with and without a diagnosis of depression as inclusion criterion.

Figure 3.

Effects of MBCT versus specific active comparison conditions at post-treatment.

Effects at longest follow-up.

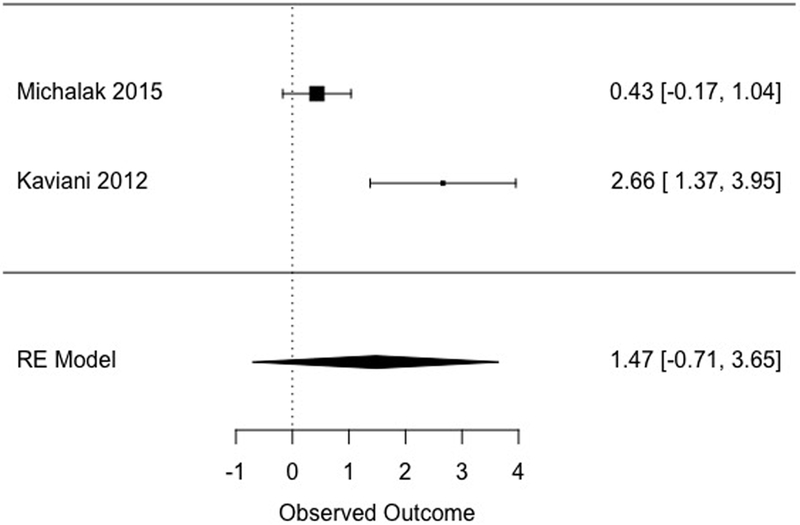

A subsample of studies (k = 5) included a follow-up assessment point. Two studies compared MBCT to a non-specific control at follow-up, showing a large but non-significant effect (d = 1.47, [−0.71, 3.65], Figure 4), with a large amount of heterogeneity (I2 = 89.40). Although one of the two studies comparing MBCT to a non-specific control at follow-up included multiple comparison conditions, a sensitivity analysis excluding this study would have left only one study (an insufficient number for meta-analytic purposes; Fu et al., 2011), and is therefore not reported.

Figure 4.

Effects of MBCT versus non-specific comparison conditions at follow-up.

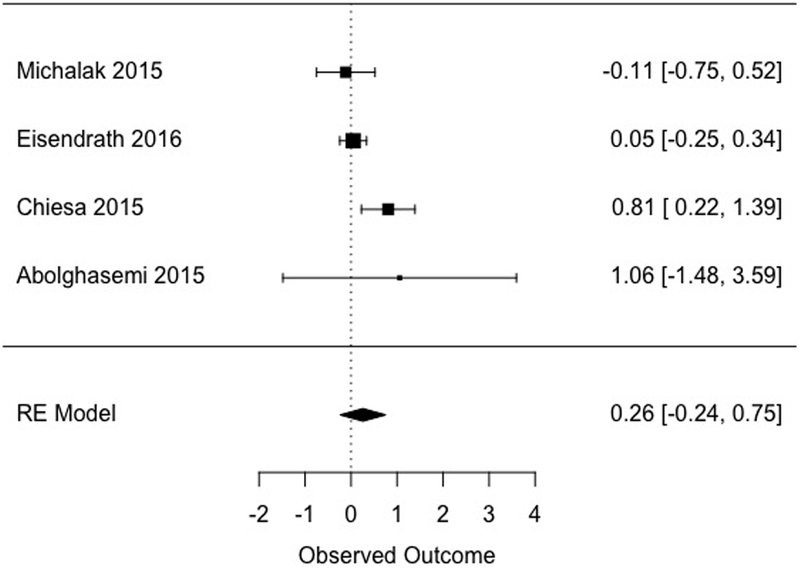

Across four studies, MBCT did not differ statistically from specific active control conditions at follow-up (d = 0.26, [−0.24, 0.75], Figure 5). Heterogeneity in this subsample was moderate to large in magnitude (I2 = 59.31).

Figure 5.

Effects of MBCT versus specific active comparison conditions at follow-up.

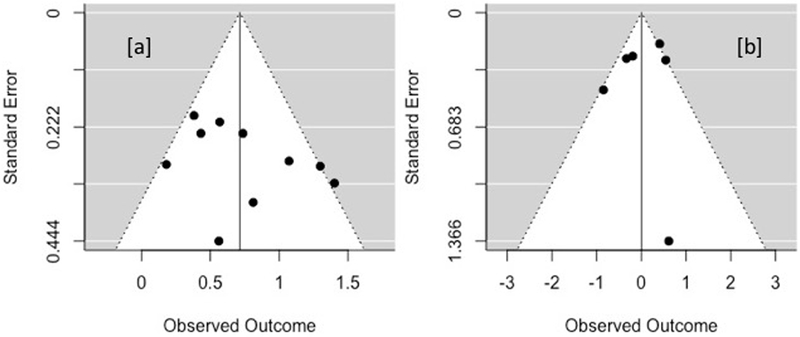

Risk of Bias Across Studies

Bias across studies was assessed through funnel plots, trim-and-fill analyses, an additional moderator analysis using modified Jadad scores, and estimation of the fail-safe N (Rosenthal, 1979). Asymmetric funnel plots suggested evidence for publication bias in one model (comparisons with specific active controls at follow-up; Figure 6 and Supplemental Materials). Modified effect sizes from trim-and-fill analyses are reported in Table 3. The significance test for the model with asymmetry did not change with this adjustment and the effect size remained largely unchanged. Study methodological quality was a significant moderator of treatment effects for comparisons with non-specific controls at post-treatment. In particular, higher quality studies showed smaller effects (B = −0.33, Q[1] = 5.66, p = .017, see Supplemental Materials). Study quality did not moderate treatment effects in any other models, although insufficient studies precluded testing moderation for comparisons with non-specific controls at follow-up. The fail-safe N was small for all models with the exception of comparisons with non-specific controls at post-treatment (fail-safe N = 239). Rosenberg (2005) provides guidelines for determining whether a given fail-safe N can be considered robust to publication bias based on the number of published studies (i.e., fail-safe N > 5n + 10, where n = the number of published studies). Based on these guidelines, the fail-safe N for non-specific controls at post-treatment is robust against publication bias (239 > 5*10 + 10).

Figure 6.

Funnel plots of post-treatment effects. (a) Non-specific; (b) specific active comparisons.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine the efficacy of MBCT specifically for patients who are currently experiencing depressive symptoms. In general, results at post-treatment (ds = 0.71 and 0.002 for non-specific and specific active controls, respectively) mirror other recent meta-analyses of MBCT (Chiesa & Serretti, 2011; Kuyken et al., 2016) such that effects for patients who are currently experiencing depressive symptoms were similar to effects for those who were in remission (Piet & Hougaard, 2011). This finding is consistent with Kuyken and colleagues’ (2016) meta-analysis that found patients in remission but with higher baseline residual depressive severity benefit from MBCT, perhaps even more so than patients with lower severity at baseline. Results are also consistent with moderate effect sizes found in recent reviews of mindfulness-based therapies (not exclusively MBCT) for depressive symptoms (Hedman-Lagerlöf, Hedman-Lagerlöf, & Öst, 2018; Wang et al., 2018) as well as meta-analyses of cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of current depression (e.g., Cuijpers, Berking, Andersson, Quigley, Kleiboer, & Dobson, 2013). Importantly, effects at post-treatment were robust to trim-and-fill analyses accounting for publication bias (an area of concern for mindfulness research; Coronado-Montoya et al., 2016), did not differ between studies requiring a diagnosis of depression vs. elevated symptoms for inclusion, and were consistent whether or not multiple comparison groups were allowed from the same study. However, it did appear that study quality impacted results in one sub-analysis: higher quality studies using a non-specific comparison group showed smaller effects at post-treatment. A high degree of heterogeneity within subgroups (I2 in the moderate to large range) was also evident, supporting the notion that further systematic differences may exist between studies.

Results at follow-up are less conclusive. MBCT was not superior to non-specific controls. Although effects were large (d = 1.47), only two small studies (combined n = 101) were available for this comparison, which raises concerns regarding the reliability of this estimate and statistical power to detect an effect. Across four studies, effects of MBCT were comparable to other active therapies at follow-up (d = 0.26). This suggests that MBCT may be of similar efficacy to other therapies that are routinely offered (e.g., cognitive therapy; Abolghasemi et al., 2015). However, given the small number of studies including follow-up time points, these findings should be interpreted cautiously. Follow-up effects did not appear meaningfully influenced by publication bias nor did methodological quality moderate observed effects for comparisons with specific active controls (these analyses were not possible for comparisons with non-specific controls due to an insufficient number of studies). Heterogeneity within subgroups was also in the moderate to large range, again implying that further systematic differences may exist between studies.

Despite uncertainty regarding the long-term effects of MBCT, primarily due to the small number of studies, effect size estimates from this meta-analysis support future research on MBCT for patients who are actively depressed. It will be crucial that future studies more clearly investigate potential mechanisms of MBCT, and the possibility that MBCT functions differently for patients who are currently depressed and those in remission (and even, perhaps, differently among those in remission with varying numbers of prior episodes, e.g., two versus three or more; Teasdale et al., 2000). Such investigations may involve exploring the neural bases of changes in depressive symptoms over the course of MBCT (Davidson, 2016). If evidence of overall equivalence of MBCT to other therapeutic interventions is confirmed in future studies, a key issue will be to determine whether individuals with specific affective or cognitive styles benefit more from MBCT compared with other interventions so that prescriptive assignment to intervention might occur. Of course, patient preferences for MBCT or other evidence-based psychotherapies may also be important to consider in clinical implementation and future research efforts (Swift & Callahan, 2009). Studies comparing MBCT (without antidepressant medications) to antidepressant medications for currently depressed individuals could also be valuable (and were surprisingly not represented in the included studies, although several studies allowed continuing medications as usual; e.g., DeJong et al., 2016).

Given that MBCT may be of similar efficacy to other active therapies for currently depressed individuals, further research could continue to examine the efficacy of MBCT in other psychiatric conditions (e.g., anxiety disorders). While a significant number of RCTs have explored MBCT for depression, far fewer RCTs have been conducted on other psychiatric conditions potentially amenable to the active treatment ingredients offered in MBCT (Goldberg et al., 2018). Numerous other psychiatric conditions share core cognitive and affective features with depression (e.g., rumination in posttraumatic stress disorder), and may therefore be positively impacted by MBCT.

Several limitations of the current study are worth noting. The primary limitations are related to the meta-analytic sample itself. There was evidence of bias in one of our analyses, with trim-and-fill results suggesting effects may have been overestimated (although the trim-and-fill adjusted effect sizes did not change the significance tests). In addition, some analyses (e.g., follow-up effects for non-specific control conditions) included very few studies, limiting statistical power and the reliability of effect size estimates. Tests of publication bias (e.g., trim-and-fill analyses) were also likely underpowered which may have limited our ability to detect bias (Sterne, Gavaghan, & Egger, 2000). There was considerable heterogeneity across studies (i.e., large I2 values), which brings into question the aggregate effect sizes as a reliable metric of treatment effects. Study quality was another concern in the meta-analytic sample. Effects at post-treatment for non-specific controls were moderated by study quality, no study included all quality features assessed, and several included only a few features, reducing confidence in the available evidence. Increasing methodological quality (see Goldberg et al., 2017 for a discussion of this issue within mindfulness research generally) will be vital in future studies of MBCT. Further, our results are only as valid as the reporting conducted in the original studies, which may be at risk for “p-hacking” and other selective reporting biases (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2011). Of course, our focus on depressive symptoms (presumably a primary outcome in all of the studies, given their focus on MBCT for depressive symptoms) may have reduced risk of some reporting biases.

Nonetheless, it is unlikely that these threats to validity alone account for the beneficial effects of MBCT observed in this meta-analysis and the apparent equivalence of MBCT with other active therapies. Future research is warranted to establish the long-term effects of MBCT for patients with current depressive symptoms which may help determine whether MBCT can be recommended for current as well as remitted depression (NICE, 2009).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Details

This work was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine under Grant P01AT004952 and the Mind & Life Institute under a Francisco J. Varela Award. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the Mind & Life Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Interest

RJD is the founder, president, and serves on the board of directors for the non-profit organization, Healthy Minds Innovations, Inc. The remaining authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional demographic feature were considered (e.g., sample average education, race/ethnicity) but were found to be inconsistently reported.

References

*Denotes study included in meta-analysis

- *Abolghasemi A, Gholami H, Narimani M, & Gamji M (2015). The Effect of Beck’s Cognitive Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Sociotropic and Autonomous Personality Styles in Patients With Depression. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 9(4), e3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Asl NH, & Barahmand U (2014). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for co-morbid depression in drug-dependent males. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28(5), 314–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S,...& The GRADE Working Group. (2003). Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: Critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Services Research, 4(38). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker B (1988). Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 41, 257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Black DS (2012). Mindfulness research guide: A new paradigm for managing empirical health information. Mindfulness, 1(3), 174–176. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0019-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, … & Larimer ME (2014). Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 547–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chiesa A, Castagner V, Andrisano C, Serretti A, Mandelli L, Porcelli S, & Giommi F (2015). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs. psycho-education for patients with major depression who did not achieve remission following antidepressant treatment. Psychiatry Research, 226(2), 474–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, & Serretti A (2011). Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 187, 441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6(4), 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- *Cladder-Micus MB, Speckens AE, Vrijsen JN,T Donders AR, Becker ES, & Spijker J (2018). Mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy for patients with chronic, treatment‐resistant depression: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Depression and Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.22788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Patel V, Joestl SS, March D, Insel TR, Daar AS, … & Glass RI (2011). Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature, 475(7354), 27–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM, Hedges LV, & Valentine JC (2009). The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado-Montoya S, Levis AW, Kwakkenbos L, Steele RJ, Turner EH, & Thombs BD (2016). Reporting of positive results in randomized controlled trials of mindfulness-based mental health interventions. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0153220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane RS, & Kuyken W (2013). The implementation of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Learning from the UK health service experience. Mindfulness, 4(3), 246–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, & Dobson KS (2013). A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 58(7), 376–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, & van Oppen P (2008). Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(6), 909–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ (2016). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and the prevention of depressive relapse: Measures, mechanisms, and mediators. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 547–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, & Kaszniak AW (2015). Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist, 70(7), 581–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *de Jong M, Lazar SW, Hug K, Mehling WE, Hölzel BK, Sack AT, … & Gard T (2016). Effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on body awareness in patients with chronic pain and comorbid depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Re AC, Hoyt WT (2010). MAd: Meta-analysis with mean differences. R package version 0.8, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MAd [Google Scholar]

- *Eisendrath SJ, Gillung E, Delucchi KL, Segal ZV, Nelson JC, McInnes LA, … & Feldman MD (2016). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(2), 99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ, … & Santaguida P (2011). Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(11), 1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, Davidson RJ, Wampold BE, Kearney DJ, & Simpson TL (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, Simpson TL, Kearney DJ, & Davidson RJ (2017). Is mindfulness research methodology improving over time? A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0187298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EM, Gould NF, Rowland-Seymour A, Sharma R,…& Haythornthwaite JA (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman-Lagerlöf M, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, & Öst LG (2018). The empirical support for mindfulness-based interventions for common psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 1–14. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718000259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, & Green S (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, & Altman DG (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ, 327(7414), 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad AR, Moore A, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, et al. (1996). Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials, 17, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delta. [Google Scholar]

- *Kaviani H, Hatami N, & Javaheri F (2012). The impact of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on mental health and quality of life in a sub-clinically depressed population. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 1(14), 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V,…Hofmann SG (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, Whalley B, Crane C, Bondolfi G,…& Dalgeish T (2016). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 565–574. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Leung A (2010). Exploring the therapeutic mechanisms of MBCT in reducing depressive symptoms: The role of habitual emotional and cognitive responses awareness. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Chinese University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- *Michalak J, Schultze M, Heidenreich T, & Schramm E (2015). A randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and a group version of cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy for chronically depressed patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 951–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, and the PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2009). Depression in adults: Recognition and management. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 [PubMed]

- *Omidi A, Mohammadkhani P, Mohammadi A, & Zargar F (2013). Comparing mindfulness based cognitive therapy and traditional cognitive behavior therapy with treatments as usual on reduction of major depressive disorder symptoms. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 15(2), 142–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Panahi F, & Faramarzi M (2016). The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on depression and anxiety in women with premenstrual syndrome. Depression Research and Treatment, 2016, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piet J, & Hougaard E (2011). The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1032–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg MS (2005). The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution, 59(2), 464–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R (1979). The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, & Dinh-Williams LA (2016). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for relapse prophylaxis in mood disorders. World Psychiatry, 15(3), 289–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal Z, Williams JW, & Teasdale J (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, & Simonsohn U (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359–1366. doi: 10.1177/0956797611417632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, & Egger M (2000). Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(11), 1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, & Callahan JL (2009). The impact of client treatment preferences on outcome: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 368–381. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale J, Segal Z, & Williams J (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(1), 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale J, Segal Z, Williams J, Ridgeway V, Soulsby J, & Lau M (2000). Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Tovote KA, Fleer J, Snippe E, Peeters AC, Emmelkamp PM, Sanderman R, … & Schroevers MJ (2014). Individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for treating depressive symptoms in patients with diabetes: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 37(9), 2427–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Van Aalderen JR, Donders ART, Giommi F, Spinhoven P, Barendregt HP, & Speckens AEM (2012). The efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in recurrent depressed patients with and without a current depressive episode: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 42(05), 989–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold B, & Imel ZE (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stich F, Benson K, & Ahn H (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “all must have prizes.” Psychological Bulletin, 122, 203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wang YY, Li XH, Zheng W, Xu ZY, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, … & Xiang YT (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for major depressive disorder: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.