Abstract

As cigarette use rates decline among adolescents and young adults, public health officials face new challenges with high use of non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTPs). Online tobacco education is a potential solution to discourage use, yet limited information is available for how online media should look and function. This study aims to fill this gap by conducting focus group interviews to identify adolescents and young adults’ aesthetic and functionality preferences for online tobacco education (phase 1) followed by interviews to assess a NCTP education website developed (phase 2). We found preferences for use of font and colors to highlight tobacco information in organized designs. Interactive features (quizzes) motivated engagement and participants desired responsive designs that function similarly across devices. Public health researchers and educators should apply aesthetic and functionality preferences to reduce NCTP use and help create a tobacco-free future for youth.

Introduction

Use of non-cigarette tobacco products (NCTPs) is high among adolescent and young adults, even as cigarette smoking rates decline [1]. Despite effective tobacco policies to reduce cigarette use, education efforts have been limited for NCTPs and many youth are unaware or have misperceptions about risks of these products [2, 3]. While a full understanding of e-cigarettes risks is forthcoming, there is clear evidence that waterpipe (hookah), cigarillos, and little cigars pose many of the same health risks as cigarettes. Use of these products increases exposure to nicotine, carcinogens, and toxic chemicals that lead to addiction and negative health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and respiratory problems [4–6].

Communication strategies that convey these risks are needed to reduce tobacco use. Digital communication is one way to reach youth where they are – online [7]. However, online education will be effective only if they secure the user’s attention and create a desire to engage.

How online information looks can greatly impact its communication effectiveness. Online first impressions based on aesthetics are made quickly and have a lasting impact for evaluations of online information [8]. Favorable first impressions encourage engagement with the health content. The reverse is true; negative first impressions often end the communication process [9]. Design can be a gateway (or barrier) to online health information.

Functionality also influences whether users will engage [10, 11]. Navigational structure and interactivity opportunities influences beliefs about the quality of the health communication and benefit of the content [12]. In turn, the functionality (usability) can both impact one’s willingness to engage and satisfaction with the website [13, 14].

With over 90% of American adolescents and young adults using smartphones [7], design guidelines for online tobacco education are needed. We conducted a two-phase study with adolescents and young adults to identify visual and interactive features that encourage engagement. In phase 1, we conducted focus groups to uncover design preference insights. In phase 2, we developed a website (suckedin.net) about the risk of cigarillos, waterpipe, and e-cigarettes and conducted interviews to evaluate our approach.

Phase One Methods

Focus Group Procedures

Four 90-minute semi-structured focus groups were conducted with 8–11 participants (n = 39). Two groups were held for adolescents (16–17 year-olds) and two for young adult (ages 18–26), with separate focus groups for tobacco users (current or lifetime) and susceptible non-users to increase homogeneity and encourage discussion. Participants were recruited from the [location blinded] via Craigslist, listservs, and local high schools. Participants between 16 and 26 years old and tobacco users (current or lifetime) or susceptible nonusers were eligible. Current users had used cigarillos or little cigars, waterpipe e-cigarettes, or cigarettes in the past 30 days. Lifetime users reported tobacco use in the past year [15]. Susceptible non-users responded “definitely yes” to “probably no” that they would use tobacco soon, in the next year, or if a best friend offered [16]. Participants were compensated $40. This study was approved by [university blinded] IRB.

Following consent (18 years or older) or parental consent and assent (16–17 years old), participants were given iPads to interact with three current websites – therealcost.com, thetruth.com, and stillblowingsmokey.org – wide-reaching online campaigns that address risks of NCTPs [17, 18]. After the viewing each website individually, participants discussed their opinions of the aesthetics and functionality. This process was repeated three times. Participants were then shown the static mock-up of our NCTP-specific website design.

Data Analysis

Focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. We used manual, open coding with an inductive analysis approach to identify emergent themes [19]. Three team members developed an initial codebook that included themes and subthemes. Two coders conducted independent parallel coding of each transcript to group segments of text by theme. Following, the team members – two coders and a third member, rotated for each transcript – reviewed all coding, settled discrepancies, and conceptualize coding into broader themes for interpretation.

Phase One Results

Participants were between 16–26 years old (M = 19.0, SD = 2.83); non-Hispanic (92.3%); and White (64.1%), multi-racial/other (17.9%), African American (15.4%), or Asian (2.6%).

Aesthetics

Layout.

Homepage layouts were most frequently critiqued; participants preferred the homepage to be organized with a minimal amount of information. One adolescent said,”[I] liked that there wasn’t too much information at once, especially on the homepage.” Participants strongly disliked overcrowded and unorganized homepages. “I felt like the homepage there was just so much, even much more the last one, just thrown at you,” according to one young adult. Another young adult agreed the websites “tried to cram too much into one space.”

Participants desired layouts with a mix of information formats. One adolescent expressed, “[I like] the fact that they varied text blocks with videos with pictures so when you scroll down there are different things to interactive with.” Participants described websites without variation as “wordy” with one young adult saying this “gets very boring after awhile.”

Font/Text Presentation.

Participants liked having a consistent font, to give “[a] sense of unity and consistency within the website,” according to one young adult. However, most liked varying font styles/sizes to highlight important information and allow for skimming. One young adult said, “it was a helpful use of font sizes… I can read one really big fact and then read the thing below it if I want, but if not I can very easily skip.” A few participants also commented that bold and italics helped split up text. An adolescent appreciated that “if you only read the bold words you got the gist of the page.”

Participants thought varying fonts conveyed tone on the websites. One young adult said, “I like on the homepage how it says “what are you really inhaling?” and then it’s like kind of fainter below… [it] kind of sounds like they’re whispering it to you.” Italics and cursive font styles conveyed sarcasm well. The overuse of bold fonts or all caps, however, conveyed a disliked yelling tone.

Color/Visual Tone.

Colors first caught most participants’ attention. Colors should be bold and contrast well, so sites are “aesthetically pleasing” and “fun to look at.” However, neon colors were distracting and discouraged further use, as an adolescent commented, “that was terrible. Very bright, obnoxiously bright.”

Color variation helped highlight important information. One adolescent said “one thing I appreciated was the small blurbs they have in different colors. I think that catches your attention without reading the entire thing” However, this had a threshold; websites could have too many colors. An adolescent expressed disliked when “ten different colors [were] jumping out at you.”

Imagery/Information Visualization.

Visuals were key to getting participants’ attention. One adolescent expressed they “didn’t even read any of [the information], I was just looking at the pictures.” For others, images help break up text. A few participants desired see more images to help visualize the facts presented; one adolescent suggested, “where it says it accounts for one in every five deaths like maybe five of those stick figures and then one of them is red.” Participants would revisit a website for the imagery, however, not for extreme or scary images.

Participants shared frustration when images appeared to contradict the message. One young adult expressed, “I’m looking at [these pictures] and thinking, you are trying to convince me not to smoke yet…here are these people like blowing smoke rings and that kind of looks cool.” Another young adult said, “I think the pictures are sending mixed signals.” Participants disliked if they could not make the connection between the image and the information. According to one adolescent, “they were trying to catch somebody’s eye, but once they [did] it was drawn to something that didn’t have anything to do with their cause.”

Social Media.

Many thought social media cues were misused or overused. An adolescent user said, “they put their social media sites three times, which is unnecessary on the page.” Participants interpreted the exaggerated presence as thinly veiled attempt to connect with youth. “I think they just want to connect with teenagers,” an adolescent user.

Functionality

Navigation.

If a website was difficult to navigate, participants were deterred from use. As one adolescent said, “because I’m already not dedicated and I’m just kind of passing by like, oh I’ll check that out, if it’s not working or if it’s not easily accessible to me I’ll just move on.” Navigation issues are especially problematic on homepages, as one young adult expressed, “trying to get out of the homepage was absurd. I couldn’t figure out if the website had more to it.” Another young adult, “the fact that more than half of the people got on the website and were like, what do I do now…is not a good sign.”

Participants were split on preferences for scrolling versus clicking through options. One adolescent shared, “[I like that] I didn’t have to click on anything, I just kept scrolling and everything I wanted was there.” However, another adolescent expressed, “I don’t like all the scrolling. The other sites I could just click once. I thought that was easier than scrolling.” In a scrolling site, a return to the top shortcut is desired. One young adult said, “[since] there’s a lot of scrolling up and down on the website…a little arrow up that you can click on to scroll back to the top could be helpful.” Participants also wanted to visual feedback for how far they have scrolled. One adolescent said, “I couldn’t see how far I had to scroll…it seemed endless.”

Overall, participants desired accessible menu bars. One young adult preferred, “it floats on top, so no matter how far you scroll up or down, [it] is always available.” Simple and clear menus, with not too many options, are ideal. One young adult said, “I like how [the menu doesn’t] have a drop down like any of the other ones. It’s just another step.” Another young adult agreed keeping menu options at a top level make it “super easy to find what you need.” Lastly, participants frequently expressed that search options were necessary. One young adult said, “I did like that there was a search bar. There wasn’t a search bar on the last one.”

Desired Interactivity.

Participants wanted features that kept them “hands on and involved,” as expressed by one young adult. Participants overwhelmingly liked quizzes and games. Informational quizzes kept them engaged; they were motivated to test their knowledge. One young adult said, “[I liked that] it’s not just one question, especially if you get one right, it’s like oh onto the next question now. That way you’re engaged but also learning.” Participants wanted more instructions for the games; many did not know how to play, or clicked out because they thought it was an ad.

Responsive Designs and Embedded Content.

Participants reported regular use their phones to search for information and wanted all websites to be mobile-friendly and responsive to their device. One adolescent said, “most times I’ll look up something, it’ll be on mobile devices of some sort, so that’s central, to have an effective [mobile] website.” Another adolescent shared, “if you want to refer a friend to this website, you don’t want [them to] go on a computer and [have it be] completely different.”

Participants wanted multimedia features – video, audio – embedded in the site. Clicking on something that navigated them away from the site discouraged participants. “I didn’t like that it linked to SoundCloud though, I wish it was like just there, and you could click play, because it took me away from the site, and then I had to go back and reload the whole thing,” said one young adult. Participants also liked the ability to hoover over areas for more information.

Phase One Discussion

Adolescents and young adults shared aesthetic and functionality preferences. For aesthetics, a simple, clean layout was desired; balance and structure can increase classical (or simplicity) aesthetic evaluations [20]. This is important for homepages, which serve as virtual front doors for first impressions [8, 14, 21, 22]. To increase appeal, homepages should feature only important information and clear navigation [13]. For all pages, a variety of visuals and text, and videos if available, can increase interest. Images that break up blocks of texts keep adolescents and young adults engaged and encourage browsing [23]. Visuals should be consistent with the website’s message. While images of products or use (e.g., teenagers blowing smoke rings) seem relevant for tobacco education sites, they send mixed signals.

Adolescents and young adults desire attention-getting colors that guide them to important content, but are distract by overly bright (e.g., neon) colors [24, 25]. As a generation of media skimmers and multitaskers [26], youth preferred differing colors and font sizes to highlight important information; this visual hierarchy serves as an implicit guide to content. The use of fonts and styles (e.g., italics) can also work effectively to convey tone, latent meaning, or personas of the text [27, 28]. For a sarcastic tone, the use of italics was well received.

Adolescents and young adults also expressed the importance of being able to easily navigate the website. With increasing experience and knowledge of technology, youth may have less patience for designs that are not easy to use [29]. If not highly motivated to explore the website, poor navigation – potentially resulting in disorientation – will lead to abandonment. A search bar and constant access to the menu increase ease of navigation [13]. Additionally, given the growing use of mobile phones to search for information, adolescents and young adults also desire websites to be mobile-friendly.

Quizzes and games were key to keeping adolescents and young adults engaged. While games are expensive, quizzes afford desired interactivity and encourage users to learn without reading large blocks of text. Adolescents and young adults liked challenging their knowledge; quizzes with immediate feedback can effectively increase engagement and learning [30]. Quizzes can also increase comprehension and feelings of risk [31, 32]. and encourage more issue-relevant thinking (than text only) through greater cognitive engagement or systematic processing [33].

Phase Two Methods

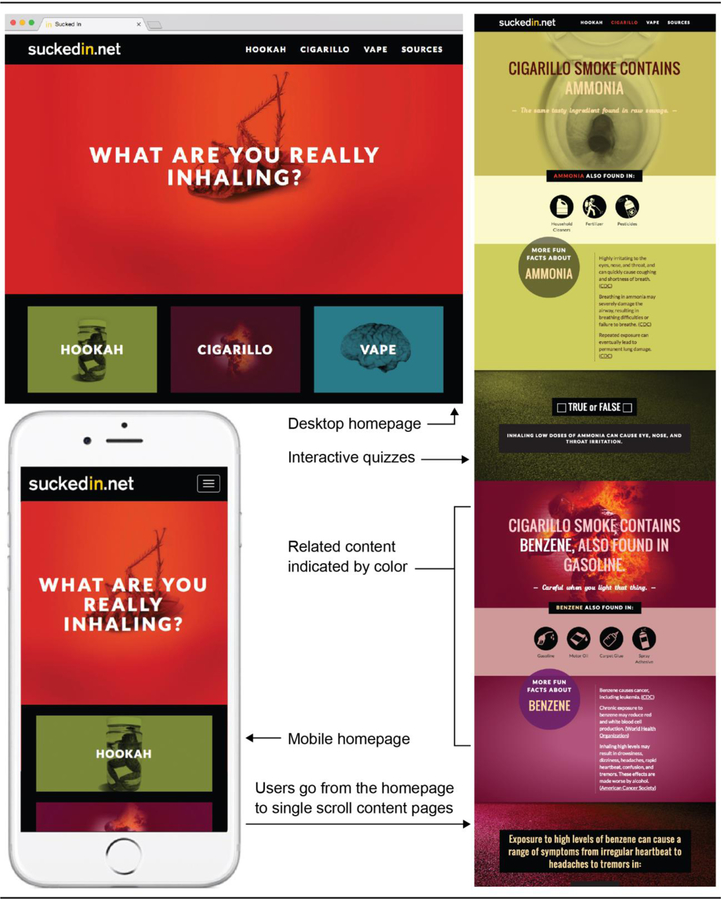

Phase one results were used to inform the design of a new website to communicate about the risk of NCTPs (Figure 1). We then conducted usability interviews with adolescents and young adults to explore reactions to the NCTP website’s aesthetics, usability, and content.

Figure 1.

Example Pages of the Non-Cigarette Tobacco Product (NCTP) Education Website

Interview Procedures

Participants were recruited using the phase one listservs, including follow-up phone calls and emails with eligible, previously screened individuals, and snowball sampling to encourage adolescent and minority participation. Following consent (18 years or older) or parental consent/participant assent (16–17 years old), participants explored the newly designed website on an iPad. Then, following a semi-structured interview guide, participants were asked about likes, dislikes and any suggestions for the website’s aesthetics, usability, and content. Participants was asked the likelihood of visiting, engaging with, or sharing this website. Lastly, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire about demographics and their tobacco use status. Tobacco users (current and lifetime) were determined by the same criteria as phase 1. All interviews were digitally recorded. Perceptions of the website aesthetics, usability, content, and whether the website would discourage tobacco use were independently coded as positive, negative, or neutral if mixed opinions were shared. Two coders established intercoder reliability – 100% agreement – with a randomly selected subset (25%) of the sample.

Phase Two Results

Participants (n=16) were 16–24 years old (M = 19.56, SD = 2.53); non-Hispanic (93.8%); and White (87.5%), African American (6.3%), or Asian (6.3%). All participants were lifetime (31.3%) or current (68.8%) tobacco users of cigarettes, little cigars or cigarillos, waterpipe, or e-cigarettes.

Adolescents and young adults found the layout, text, and colors of the newly designed website visually appealing and kept them interested in the site. Participants though the website was “perfected and ready to go” and “really clean and organized.” One young adult expressed appreciated for the amount of text, if there was “any more, [she’d] start skimming,” while another young adult commented that design encourages users “to keep going if only to see what cool colors or graphic would come next.” There was some concern again of images contradicting the website’s message, especially if showing vapor. One young adult described the vapor as “visually appealing” and “the smoke being purple made it look kind of cool.” This same young adult expressed that the image didn’t “make [her] want to go buy a vape, but it wasn’t making [her] not want to go buy [one].” Only one participant had a negative impression: the colors were overwhelming, while the “format and the text size is nice.”

Adolescents and young adults agreed the site was easy to use, with each of the 16 interview participants providing a positive review of the website usability and functionality. Participants favored the one-page scroll, with one young adult commenting “with today’s technology it’s a lot easier to scroll…so this is more accessible and easy to use.” Participants also liked the easy access to and simplicity of the menu options. For example, one adolescent expressed that “the lack of drop down menus made it easier.” However, a few usability problems were also uncovered; quizzes required a double click for the right answer to be shown, which was described by one young adult as “not intuitive” Functionality issues aside, young adults expressed that the quizzes were “clever” and “make you sort of pay attention” and would encourage them to”[go] back and read [the information].”

Overall, most participants (69%) believed the website would effectively discourage NCTPs use. As one participant stated, “If I even considered smoking cigarillos, this would make me not want to do it anymore.” Some participants expressed the site would be more effective as a tool to prevent NCTP use than to get current users to quit. Of the few people who questioned the effectiveness of the website to discourage NCTP use, one felt the content was not novel enough, stating, “If I had known nothing about [NCTPs] and I read this, it probably would discourage me from using the products, but because I know information about [NCTPs]… this didn’t like enhance my discouragement.” Most interviewees (81%) also liked the website content, but others wanted additional information to compare these tobacco products to cigarettes, specific information about dose and toxicity of different ingredients, or additional resources that they could explore. All users stated they would be willing to share the website with a friend who was either considering using NCTPs or trying to quit. Almost all participants said they would share through a text message, Facebook message, or in-person rather than a public link to the website.

General Discussion

Given the tremendous reach of the internet and impact of mass media campaigns on reducing smoking [18], online tobacco education may be an effective approach communicate the dangers of tobacco use, including risks of NCTP. However, there is little evidence or guidance for how websites should be designed to appeal to youth. To address this, we conducted focus groups with adolescents and young adults to identify online tobacco education preferences. We then applied these findings and conducted interviews to gauge responses to the aesthetics, usability, and content of a newly developed site.

Findings are limited to the opinions of adolescents and young adults in this study. Adolescents and young adults’ preferences for online tobacco education messaging may differ by region, racial, or socioeconomic backgrounds. Specifically, the lack of Hispanic (both phases) and non-White participants (phase 2) limits this study’s findings. Future studies should consider other recruitment strategies for diverse audiences: Leveraging community centers and organizations, including neighborhood-based sampling and recruiting through faith-based organizations, has been shown to encourage African American and Hispanic participation [34–37]. Doing so would also allow for face-to-face tailored referrals and interviews conducted on-site at these organizations, reflecting the need for flexibility and autonomy among youth, minority, and other vulnerable populations.[36, 38] An implied consent process in high schools may also help reduce participation disparities among youth in tobacco control research [39, 40]. Additionally, all preferences were self-reported. Future work should incorporate behavioral measures (e.g., web analytics) to assess the impact on actual use.

Conclusion

Adolescents and young adults in this study had clear preferences for how online tobacco education should look and function. Responsive designs with well-organized, uncluttered layouts and clear navigation cues are necessary for a seamless user experience. Using consistent, and limited, fonts and color palettes are preferred; design elements should vary in size, weight, and color to guide users to important information. Images that communicate key information should be selected over sensational options (e.g., infographics vs. scary images). It is equally important to avoid imagery that communicates unintended messages (e.g., showing e-cigarettes alongside candy), even when the text resolves the contradiction – youth might not continue reading. Social media conventions (e.g., hashtags) should be applied cautiously; a misused or outdated convention signals inauthenticity. Lastly, quizzes motivate users to engage with and encouraging learning. The findings provide guidelines for online tobacco education to increase favorable impressions and engagement among adolescents and young adults.

References

- 1.Singh T, Arrazola R, Corey CG, et al. 2016. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 65: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornacchione J, Wagoner KG, Wiseman KD, et al. 2016. Adolescent and young adult perceptions of hookah and little cigars/cigarillos: Implications for risk messages. Journal of Health Communication 21: 818–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagoner KG, Cornacchione J, Wiseman KD, et al. 2016. E-cigarettes, hookah pens and vapes: Adolescent and young adult perceptions of electronic nicotine delivery systems. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 18: 2006–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montazeri Z, Nyiraneza C, El-Katerji H, et al. 2017. Waterpipe smoking and cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Tobacco Control 26: 92–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisinger C and Døssing M. 2014. A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Preventive Medicine 69: 248–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CM, Corey CG, Rostron BL, et al. 2015. Systematic review of cigar smoking and all cause and smoking related mortality. BMC Public Health 15: 390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Research Center. 2018. Mobile fact sheet February 5, 2018; Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/mobile/.

- 8.Lindgaard G, Fernandes G, Dudek C, et al. 2006. Attention web designers: You have 50 milliseconds to make a good first impression! Behaviour and Information Technology 25: 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sillence E, Briggs P, Harris P, et al. 2007. Going online for health advice: Changes in usage and trust practices over the last five years. Interacting with computers 19: 397–406. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer JW 2002. Web site usability, design, and performance metrics. Information Systems Research 13: 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo K-K, Lee S, Chung BD, et al. 2015. Users’ emotional valence, arousal, and engagement based on perceived usability and aesthetics for web sites. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 31: 72–87. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eysenbach G 2005. Design and evaluation of consumer health information web sites. In Consumer Health Informatics, 34–60. Springer: New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webster J and Ahuja JS. 2006. Enhancing the design of web navigation systems: The influence of user disorientation on engagement and performance. MIS Quarterly 30: 661–678. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu N and Kong J 2016. User experience with web browsing on small screens: Experimental investigations of mobile-page interface design and homepage design for news websites. Information Sciences 330: 427–443. [Google Scholar]

- 15.King BA, Patel R, Nguyen K, et al. 2014. Trends in awareness and use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2013. Nicotine & Tobacco Research ntu191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. 1996. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology 15: 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duke JC, Alexander TN, Zhao X, et al. 2015. Youth’s awareness of and reactions to The Real Cost national tobacco public education campaign. PLoS One 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Duke J, et al. 2009. Sustaining ‘truth’: changes in youth tobacco attitudes and smoking intentions after 3 years of a national antismoking campaign. Health Education Research 24: 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DR. 2006. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27: 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moshagen M and Thielsch MT. 2010. Facets of visual aesthetics. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 68: 689–709. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazard AJ and Mackert M 2015. E-health first impressions and visual evaluations: Key design principles for attention and appeal. Communication Design Quarterly 3: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen J 2003. The ten most violated homepage design guidelines Available from: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/most-violated-homepage-guidelines/

- 23.Minear M, Brasher F, McCurdy M, et al. 2013. Working memory, fluid intelligence, and impulsiveness in heavy media multitaskers. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 20: 1274–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seckler M, Opwis K and Tuch AN. 2015. Linking objective design factors with subjective aesthetics: An experimental study on how structure and color of websites affect the facets of users’ visual aesthetic perception. Computer in Human Behavior 49: 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson RT, Drexler TL and Delparte DM. 2014. Color and contrast in E-Learning design: A review of the literature and recommendations for instructional designers and web developers. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 10: 657–669. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ralph BC, Thomson DR, Cheyne JA, et al. 2014. Media multitasking and failures of attention in everyday life. Psychological Research 78: 661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juni S and Gross JS. 2008. Emotional and persuasive perception of fonts. Perceptual and Motor Skils 106: 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brumberger E 2003. The rhetoric of typography: The persona of typeface and text. Technical Communication 50: 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson J and Rainie L 2012. Main findings: Teens, technology, and human potential in 2020 Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/02/29/main-findings-teens-technology-and-human-potential-in-2020/.

- 30.Scacco JM, Muddiman A and Stroud NJ. 2016. The influence of online quizzes on the acquisition of public affairs knowledge. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 13: 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lustria MLA. 2007. Can interactivity make a difference? Effects of interactivity on the comprehension of and attitudes toward online health content. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 58: 766–776. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ancker JS, Chan C and Kukafka R 2009. Interactive graphics for expressing health risks: Development and qualitative evaluation. Journal of Health Communication 14: 461–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh J and Sundar SS. 2015. How does interactivity persuade? An experimental test of interactivity on cognitive absorption, elaboration, and attitudes. Journal of Communication 65: 213–236. [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCleary-Sills JD, Villanti A, Rosario E, et al. 2010. Influences on tobacco use among urban Hispanic young adults in Baltimore: Findings from a qualitative study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 4: 289–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou S-I and Cao X 2018. A systematic review of promising strategies of faith-based cancer education and lifestyle interventions among racial/ethnic minority groups. Journal of Cancer Education 33: 1161–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders J and Munford R 2017. Hidden in plain view: Finding and enhancing the participation of marginalized young people in research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ewing A, Thompson N and Ricks-Santi L 2015. Strategies for enrollment of African Americans into cancer genetic studies. Journal of Cancer Education 30: 108–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rait MA, Prochaska JJ and Rubinstein ML. 2015. Recruitment of adolescents for a smoking study: Use of traditional strategies and social media. Translational Behavioral Medicine 5: 254–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diviak KR, Wahi S, and O’Keefe J, et al. 2006. Recruitment and retention of adolescents in a smoking trajectory study: Who participates and lessons learned. Substance Use & Misuse 41: 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unger JB, Cabassa L, Molina G, et al. 2000. English language use as a risk factor for smoking initiation among Hispanic and Asian American adolescents: Evidence for mediation by tobacco-related beliefs and social norms. Health Psychology 19: p. 403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]