Abstract

Native plant species were screened for their remediation potential for the removal of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) contaminated soil of Bagnoli brownfield site (Southern Italy). Soils at this site contain all of the PAHs congeners at concentration levels well above the contamination threshold limits established by Italian environmental legislation for residential/recreational land use, which represent the remediation target. The concentration of 13 High Molecular Weight Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in soil rhizosphere, plants roots and plants leaves was assessed in order to evaluate native plants suitability for a gentle remediation of the study area. Analysis of soil microorganisms are provides important knowledge about bioremediation approach. Alphaproteobacteria, Betaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria are the main phyla of bacteria observed in polluted soil. Functional metagenomics showed changes in dioxygenases, laccase, protocatechuate, and benzoate-degrading enzyme genes. Indolacetic acid production, siderophores release, exopolysaccharides production and ammonia production are the key for the selection of the rhizosphere bacterial population. Our data demonstrated that the natural plant-bacteria partnership is the best strategy for the remediation of a PAHs-contaminated soil.

Subject terms: Abiotic, Environmental impact

Introduction

“Intense industrial activities in the 20th century has been particularly deleterious to the environment, resulting in a large number and variety of contaminated sites”. Furthermore, once these industrial areas have been abandoned, the contamination with substances that are dangerous for the environment and for human health remains. Heavy Metals (HMs), PolyChloroBiphenyls (PCB) and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) can pollute former industrial area. All these compounds can be formed both by anthropogenic activities and by natural emissions. Anthropogenic origins include petrogenic and pyrolytic (which represents the main process responsible of PAHs contamination) origin. Pyrolytic origins comprise partial combustion of organic matter (such as fossil fuels and biomass) mainly occurring during industrial and other human activities. While the petrogenic PAHs are constitute by petroleum products, such as accidental oil spills, discharge from routine tanker operations, municipal and urban runoff1,2.

For all these reasons, PAHs are among the most commonly studied groups of organic pollutants frequently found in abandoned industrial areas. These compounds are environmentally persistent with various structures (two or more fused benzene rings) and varied toxicity. They represent an important health risk since they can enter the food chain (resulting in bioaccumulation and biomagnification). In soils, PAHs have a low mobility and high durability and their amount depends of different factor as temperature, pH, and soil organic matter content3,4 and ageing of the history of contamination in soils5. Nowadays brownfields recovery sites represents a challenging issue throughout the world, which has gained increasing attention in recent years in order to prevent contaminants migration and to allow redevelopment6,7. At the same time, brownfields are attractive for site planning (since they are often situated in areas adjacent to the central parts of the cities)8.

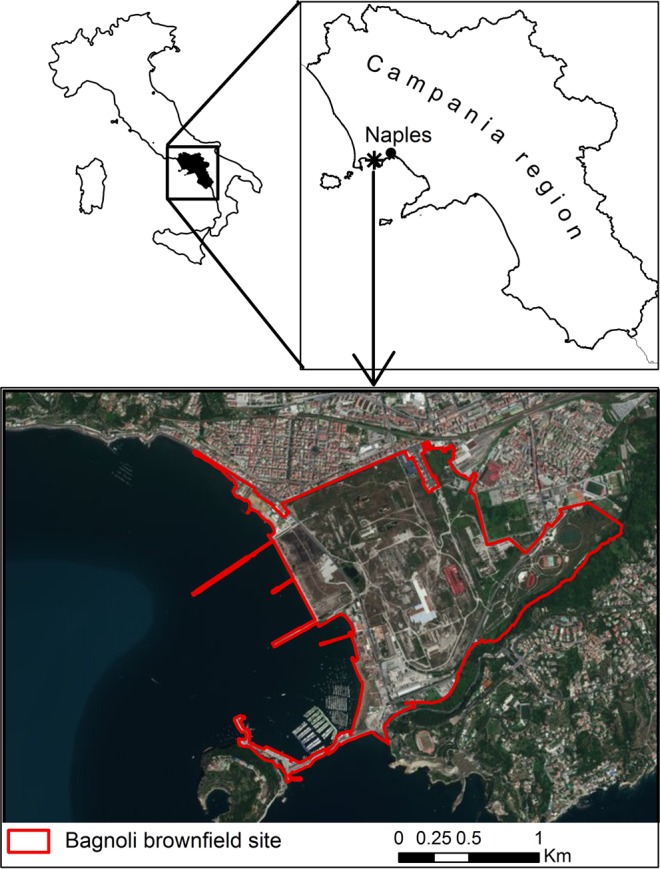

Bagnoli, abandoned industrial area, represent one of the main brownfield site in Italy. Its steel plant (overlooking the Gulf of Naples) was for a century, until its demise in the mid-1990s, Italy’s largest one (Fig. 1). Unluckily, the products and by-products of industrial processes changed the natural equilibrium environment9, so its remediation has become a priority. Among the different remediation technologies, an in-situ bioremediation approach has been chosen and is ongoing to clean-up soils of Bagnoli brownfield site. This bioremediation strategy uses live plants (woody or herbaceous plant) and microorganisms populations that naturally live in the soil that are adapted to the contamination to recover the polluted areas; is non-destructive and environmentally/eco-friendly and represent an interesting research field, which results has been considerably documented over the last decades8,10,11. Different bacteria, naturally present in soil, are able to degrade PAHs as alpha, Beta and Gamma Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes12. Among Protobacteria, Betaproteobacteria are the best to PAH degradation13,14. Burkholderiales are especially well known to degrade PAHs15,16. In addition, Gammaproteobacteria are able to degrade PAHs17.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area (Bagnoli brownfield site, Southern Italy). From Google Maps (https://www.google.com/maps/place/80124+Bagnoli+NA/@40.8171802,14.1516033,5444m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x133b0e97616d81eb:0xb53d31e14d5424cd!8m2!3d40.8171821!4d14.1691129).

The main objectives of this study are: (i) discrimination of contamination levels and origins of PAHs in the analysed soils; (ii) native PAHs tolerant plants identification; (iii) identification of natural bacterial communities in PAHs contaminated soils; (iv) identification of their Plant Growth Promoting (PGP) attributes; (v) identification of main enzymes produced by native microbiota of a soil polluted with PAHs; (vi) selection of the better system for phytomanagement of the study area.

Results and Discussion

Distribution of PAHs in rhizosphere soils

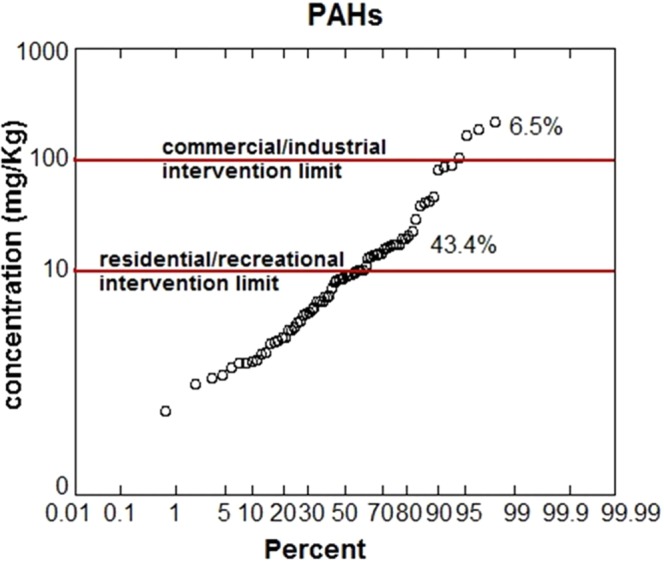

The Italian legislation (Legislative Decree 152/06) provide two threshold limits for ∑PAHs: 10 and 100 mg/kg for recreational and commercial land use, respectively. Data produced within this study (set up by Italian Government) show that 43.4% of the analysed soils are characterized by ∑PAHs above the residential/recreational limit (Fig. 2); also, the commercial/industrial land use threshold is exceeded by a percentage of 6.5% of total samples. Based on Italian Government remediation objective (which correspond to residential/recreational land use recovery of the area) site contamination is mainly governed by higher molecular weight PAHs congeners BghiP > BaP > IcdP (Fig. 3). In addition, the commercial/industrial threshold limit is exceeded by several congeners (except for DaeP, DaiP, DalP, DahA, Pyr and Chr) (Fig. 3). Table 1 listed the mean statistical parameters of the measured PAHs concentrations in the rhizosphere soil. Our results showed that the mean concentrations of Pyr (3.37 ± 0.78 mg/kg), BbF (3.32 ± 0.66 mg/kg), Chr (2.68 ± 0.59 mg/kg), BaP (2.43 ± 0.53 mg/kg) and BaA (2.34 ± 0.51 mg/kg) were significantly higher in rhizosphere soils. The concentration levels of analysed rhizosphere soils reveal a strong PAHs pollution. They were among the highest ones compared to the literature reported values for other contaminated soils of other areas in the world (Table S1- Supplementary Material), which suggest a strong anthropogenic input from industrial activities on the study area.

Figure 2.

Probability distribution and local density of soil ∑PAHs data produced by site characterization (set up by Italian Government). The X-axis is scaled in probability (between 0 and 100%) and shows the percentage of the Y variable whose value is less than the data point. The Y-axis displays the range of the data variables.

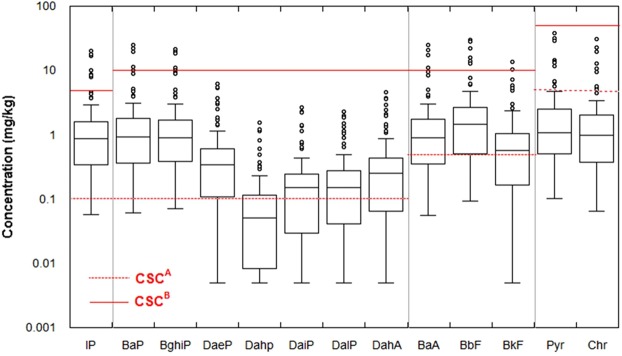

Figure 3.

PAHs congeners’ concentration levels of soil PAHs data produced by site characterization (set up by Italian Government). Dashed and continued lines correspond to threshold limit for residential/recreational and commercial/industrial land use (Legislative Decree 152/06), respectively.

Table 1.

Measured concentration of PAHs (mg/kg) in the rhizosphere soil from Bagnoli brownfield site.

| Compound | Rizhosphere soils | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Mean | SE | |

| BaA | 0.055 | 24.7 | 2.34 | 0.51 |

| BaP | 0.061 | 24.8 | 2.43 | 0.53 |

| BbF | 0.094 | 30.0 | 3.32 | 0.66 |

| BkF | 0.005 | 13.7 | 1.35 | 0.28 |

| BghiP | 0.07 | 21.7 | 2.32 | 0.48 |

| Chr | 0.064 | 31.0 | 2.68 | 0.59 |

| DahA | 0.005 | 4.6 | 0.54 | 0.10 |

| IP | 0.057 | 20.2 | 2.14 | 0.44 |

| Pyr | 0.101 | 38.0 | 3.37 | 0.78 |

| DaeP | 0.005 | 6.3 | 0.75 | 0.14 |

| Dahp | 0.005 | 1.54 | 0.14 | 0.03 |

| DaiP | 0.005 | 2.7 | 0.29 | 0.06 |

| DalP | 0.005 | 2.32 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| ∑ PAHs | 0.5746 | 221.5 | 21.9 | 4.70 |

Instrumental Detection Limit (IDL) is 0.01 mg/kg. For statistical computation, data below the instrumental detection limit (IDL) were assigned a value corresponding to 50% of the detection limit.

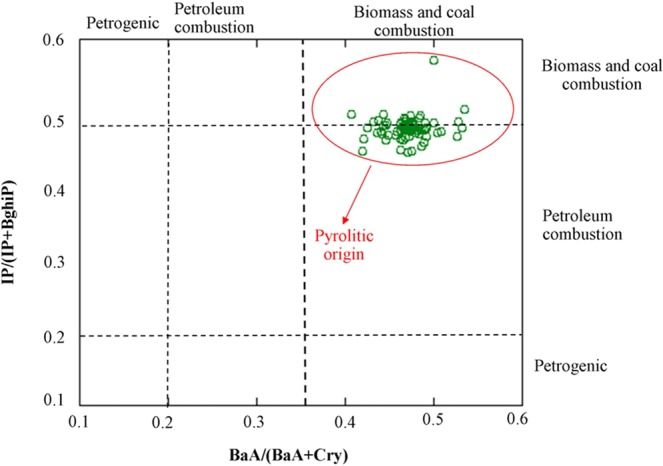

PAHs sources

The combined use of the diagnostic ratios allowed us to PAHs origin of the investigated area. BaA/(BaA + Chr) ratios ranged from 0.40 to 0.53, presenting ratios characteristic of pyrogenic source. This is also supported by looking at IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) ratios, ranging from 0.44 to 0.57 for which origins of PAHs are more likely to be related to coal/biomass and petroleum combustion. Indeed, the analysed soils show an unmistakable pyrogenic origin (Fig. 4) related to past industrial processes including dust, ash, carbon coke residues, heavy oils, hydrocarbons, and combustion residues. Fingerprint of coal combustion as reported by Vivo and Lima9 is clearly highlighted by adopted diagnostic ratios.

Figure 4.

Cross-plots for the isomeric ratios of IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) versus BaA(BaA + Chr) for soil PAHs source characterization.

PAHs in the plants system

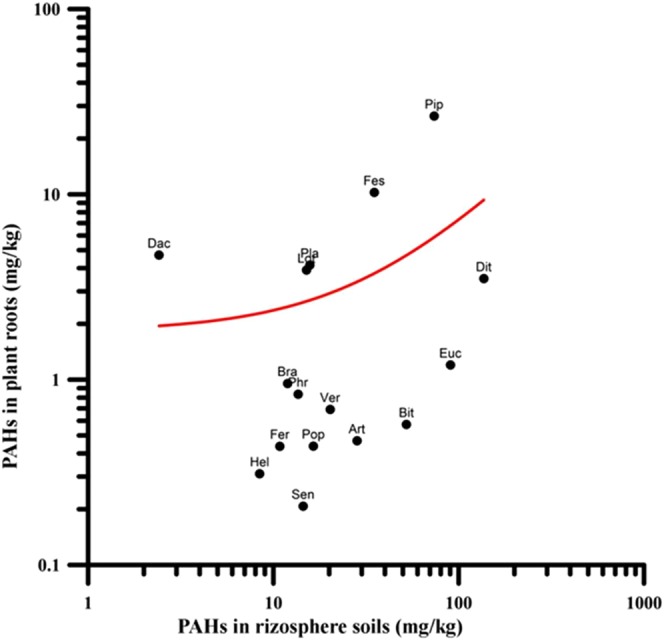

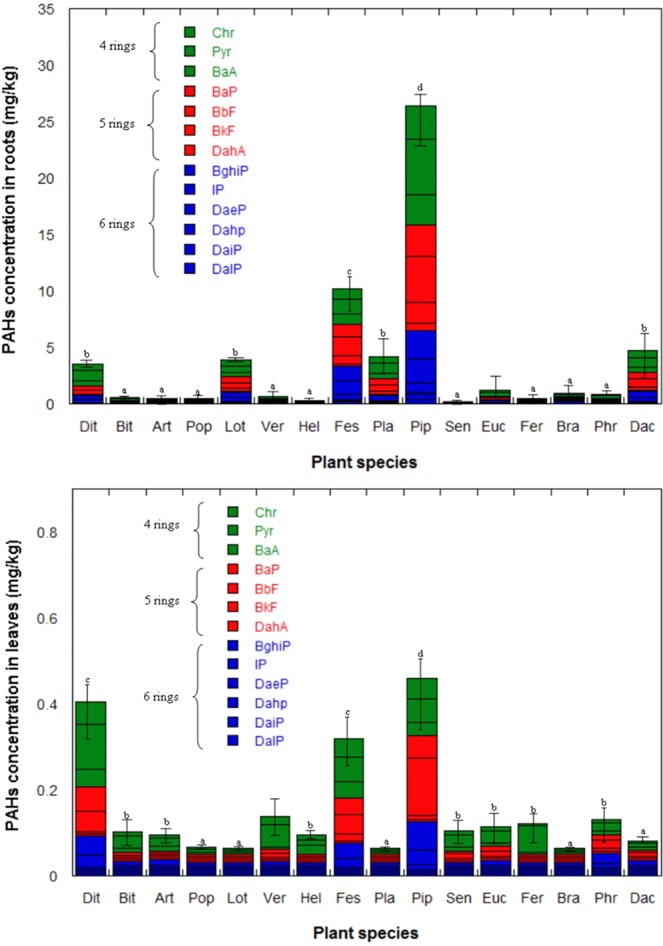

The families more present in the Bagnoli brownfield site are Poaceae (20 taxa, 14.4%), Fabaceae (15 taxa, 10.8%), Asteraceae (14 taxa, 10.1%) and Apiaceae (6 taxa, 4.3%). These plants are adapted and able to survive and reproduce under contaminated soil condition18. PAHs concentrations in the plant system (root and leaves) were determined for 16 native plant species. Pearson correlation analysis suggested a positive correlation (with a Pearson coefficient of 0.63 and 0.64 at p < 0.001, respectively) between PAHs content in plants roots and leaves and the related rhizosphere soil. The scatterplot of Fig. 5 highlights that roots accumulation is promoted by both soil contamination levels and plant species. Figure 6 highlight PAHs accumulation in roots and leaves respectively by analysed plant species. The different profiles of PAHs in plant tissues indicated that the 4-ring and 5-ring PAHs mostly contributed to total concentration of PAHs in both roots and leaves. Higher molecular weight PAHs are generally incapable of translocation to the aboveground plant parts because of their low water solubility, and they are strongly bound to the roots19. An organic element enters a plant roots for the presence of the lipid in a plant that, even at small amounts, is usually the principal source for highly water-insoluble contaminants20. Lin et al.21 demonstrated that the storage of PAHs in maize plant (Zea maize L.) was directly congruent to the lipid level in tissues that allows the free diffusion within cells.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot showing the relationship between ∑PAHs concentration in the rhizosphere soils and in plant roots for selected native species – data represent the mean value of 3 replicates.

Figure 6.

PAHs concentrations (mg/kg) in roots and leaves. Columns with the same letter are not significantly different at p < 0.05, according to ANOVA-protected Tukey’s post hoc test. Error bars indicate Standard Error (SE).

In a recent studies22,23 shown that seeds of Zea mays are ecotoxicity indicator on soils contaminated with petro derivates.

As the PAHs, level in leaves is roughly not significative; our interest must focus on root system. Among the analysed plant species, Pip and Fes show the highest ΣPAHs root concentration, with mean content of 26.4 and 10.2 mg/kg, respectively. However, Dac demonstrates to be the best root bioaccumulator. In addition, Lot and Dit show promising ΣPAHs root phytostabilization rates (Fig. 6). Pip has suitable attributes like as fast growth and high root cover; in addition, it is able to stimulate soil microbial communities24,25.

The considerable PAHs content in roots was not only imputable to the contamination by adherent soil particles. However, as suggested by Fismes et al.26 it is possible that part of the PAHs measured in plants roots can be due to their adsorption on the roots epidermis. “In fact, root peels are mainly made of suberin, a polyester with phenolic and aromatic functions presenting a lipophilic pole27 able to strongly adsorb PAHs28,29”.

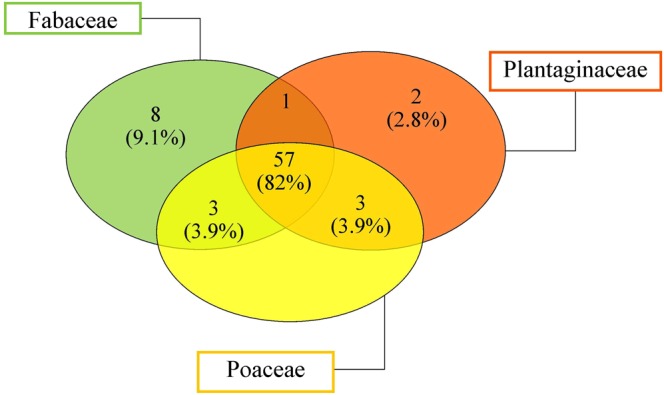

Soil bacteria community

A natural bioremediation process is defined by the rating of bacterial functional and structural diversity in soil directly from the contaminated site. Rhizosphere soil collected from three different plants (Pip, Lot and Pla) that are present in Bagnoli brownfield were characterized by abundant biodiversity for approximately 93–97% of the total biodiversity in each sample. The Venn diagram for the bacterial populations of the three-rhizosphere soils of three different plants is shown on Fig. 7. In the soils collected directly from three plants (Pip, Lot and Pla), 82% of the bacterial communities were found to be in common. Therefore, the microbial community composition were highly heterogeneous. The analysis of soils showed that within Proteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria were the taxa with higher proportions, both containing known species of PAH degraders and Actinobacteria populations as well. Firmicutes and Deltaproteobacteria were relatively less of all other groups (Table 2). All three rhizosphere soils investigated showed Gammaproteobacteria as the most abundant class with Pseudomonadaceae family. In literature is known the use of Pseudomonas genera employed in bioremediation study of soil polluted by PAHs30 reported that the degradation of complex mixtures could be done using a pool of bacteria with different functions and capacity to utilize as source of carbon and energy the hydrocarbons31–33. Because the endophyte communities is mainly present in phylum Proteobacteria34, we hypothesize that our identified bacteria, belonging for 82% to phylum of Proteobacteria, could act as endophytes. In Table 2 there are the main genera of bacteria that behave like endophytes, Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Burkholderia, Rhizobium and Microbacterium34–38. A good method to reduce crude oil is a biodegradation process via cometabolism. Gałazka et al.30 and Doong and Lei39 reported that in case of cometabolism hydrocarbons could not be a font of carbon and energy but has function as co-substrates, so their degradation is due by the presence of diverse microorganisms (e.g. parathion is cometabolized by Pseudomonas stutzeri to 4-nitrophenol and diethylphosphate, and phenol is then used as a source of carbon and energy by P. aeruginosa); the researcher conclude that cometabolism is one of the most important mechanism in the transformation of PAHs in soil. Pseudomonas aeruginosa make PAH-oxidative enzymes and release rhamnolipids40. Bacillus cereus degrade both LMW and HMW PAHs41,42. Besides, Cavalcanti et al.43 emphasizing the adjunct of consortia composed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia strains in the removal of phenanthrene and pyrene from a soil contaminated by a lubricating oil mixture containing PAH. In polluted soil the presence of Alphaproteobacteria, family as Bradyrhizobiaceae (slow-growing rhizobia), Rhizobiaceae, Nitrobacter and Sphingobium, known in literature to do nodules on the roots of leguminous plants and fixing nitrogen, is important. Komaniecka et al.44 called “bacteroids” the endosymbiotic rhizobia, in which nitrogen fixation takes place. All bacterial species isolated in this study are known to be a good PAHs degradation45. Different paper reported the import role of bacterial consortium. Vaidya et al.46 reported the use of Pseudomonas, Burkholderia and Rhodococcus (PBR) was able to degrade 99% of pyrene under microcosm conditions. Other consortiums like Pseudomonas sp. and Bacillus sp. isolated from oil sludge that are able to reduce total petroleum hydrocarbons from 63 to 84% in six weeks47; and the consortium composed of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Rhodococcus sp. isolated from soil polluted with oily sludge demonstrated 90% degradation of hydrocarbons in 6 weeks47. Plant roots release exudates as sugars, organic acids, fatty acids, secondary metabolites, nucleotides and inorganic mixture that perform an important key in establishing and determining the rhizosphere microbial population48. These exudates determine and regulate directly or indirectly the activity of biodegradative microorganisms. In this study, the capability of isolates strain to make indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, exopolysaccharides and ammonia was evaluated (Table 2). Thirty-nine of the isolates were able to produce Indolacetic acid (IAA). All three-rhizosphere soil had Paenibacillus polymyxa as the best IAA producing. Both in Poaceae and in Plantaginaceae rhizosphere soil Rhizobium leguminosaurum produced highest amount of IAA. Mycobacterium sp. MOTT36Y, instead, produced only in Poaceae family highest amount of IAA. Rhizosphere of Plantaginaceae and Fabaceae had Pseudomonas cichorii as good IAA producer. Plantaginaceae and Fabaceae showed respectively typical strains with high IAA Paenibacillus sp. JDR-Z, Bacillus cereus group, Klesbiella aerogenes for the first and Rhizobium etli bv mimosae for the second one. In this study, the 60% of isolates were found to have ability for siderophores production. Rhodococcus jostii produced in all three-rhizosphere soils high amount of siderophores; only in Plantaginaceae, also Bacillus cereus group showed siderophores activity. The three-rhizosphere soils showed 50% of isolates capable of producing EPS. The high amount of EPSs production was present in Burkholderia cenocepacia, Burkholderia ambifaria AMMD, Bacillus cereus group, Sinorhizobium fredii, Sinorhizobium meliloti. Only the 38% of isolates displayed the production of ammonia. The high amount of ammonia was in Burkholderia pseudomallei NCTC 13178 and Bacillus cereus group.

Figure 7.

Venn-diagram showing the intersection of isolated bacteria from rhizosphere soils of the three main plant families found in Bagnoli brownfield site (Fabaceae, Plantaginaceae and Poaceae).

Table 2.

Primary screening of the assessment of potential PGP by bacteria isolates recovered from rhizosphere soil of Piptatherum miliaceum, Lothus corniculatus and Plantago lanceolata.

| Bacterial isolates | Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genus | Production IAA | Siderophore release | EPSs production | Production of ammonia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA6 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | Rhizobiales | Bradyrhizobiaceae | Bradirhizobium | ++ | − | − | ++ |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||

| Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |||||

| Bradyrhizobium oligotrophicum | ++ | ++ | + | + | |||||

| Bradyrhizobium oligotrophicum S58 | + | − | + | − | |||||

| Nitrobacter hamburgensis | Nitrobacter | − | — | − | − | ||||

| Nitrobacter hamburgensis X14 | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Rhizobium leguminosaurum | Rhizobiaceae | Rhizobium | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||

| Rhizobium leguminosarum bv trifolii | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||

| Rhizobium leguminosarum bv trifolii WSM2304 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||

| Rhizobium etli CIAT652 | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Rhizobium etli bv mimosae | − | ++ | − | − | |||||

| Sinorhizobium fredii | Ensifer | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||||

| Sinorhizobium meliloti | − | ++ | − | − | |||||

| Mesorhizobium ciceri | Phyllobacteriaceae | Mesorhizobium | − | − | − | − | |||

| Achromobacter xylosoxidans | Beta Proteobacteria | Bukholderiales | Alcaligenaceae | Achromobacter | ++ | ++ | − | − | |

| Burkholderia cenocepacia | Burkholderiaceae | Burkholderia | + | − | − | − | |||

| Burkholderia ambifaria AMMD | − | + | + | — | |||||

| Burkholderia pseudomallei NCTC 13178 | + | − | − | ++ | |||||

| Burkholderia gladioli | + | − | − | + | |||||

| Burkholderia glumae BGR1 | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Paraburkholderia rhiroxinica | Paraburkholderia | − | − | ++ | ++ | ||||

| Paraburkholderia xenovorans | + | + | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Gammaproteobacteria | Pseudomonadales | Pseudomonadaceae | Pseudomonas | + | + | − | − | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA7 | − | ++ | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas stutzeri | − | +++ | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas mendocina NK-01 | ++ | ++ | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas resinovorans | ++ | ++ | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas resinovorans NBRC 106553 | +++ | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens SBW25 | − | ++ | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 | − | ++ | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas poae | − | + | + | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas putida | − | + | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas putida H8234 | − | + | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas putida NBRC 14164 | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas putida GB-1 | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas putida HB3267 | +++ | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas fulva 12-X | + | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas stutzeri DSM 10701 | + | − | − | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas stutzeri DSM 4166 | + | + | + | ||||||

| Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501 | + | + | − | + | |||||

| Pseudomonas syringaepv.tomato | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas brassicacearum | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas pertucinogena group | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | |||||

| Pseudomonas cichorii | +++ | + | ++ | − | |||||

| Enterobacter aerogenes | Enterobacteriales | Enterobacteriaceae | Klesbiella | ++ | − | +++ | + | ||

| Geobacter bemidjiensis | Deltaproteobacteria | Desulfuromonadales | Geobacteriaceae | Geobacter | ++ | − | +++ | + | |

| Rhodococcus opacus B4 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria | Actinomycetales | Nocardiaceae | Rhodococcus | ++ | − | − | + |

| Rhodococcus jostii | + | ++ | + | + | |||||

| Rhodococcus pyridinivorans sb3094 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||||

| Mycobacterium abscessus subsp bolletii | Mycobacteriaceae | Micobacterium | ++ | + | ++ | + | |||

| Paenibacillus mucilaginosus K02 | Firmicutes | Bacilli | Bacillales | Paenibacillaceae | Paenibacillus | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Paenibacillus mucilaginosus 3016 | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Paenibacillus sp JDR-2 | − | − | − | − | |||||

| Paenibacillus polymyxa | + | ++ | ++ | + | |||||

| Bacillus cereus group | Bacillaceae | Bacillus | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |||

| Bacillus thuringiensis serovar finitimus | ++ | − | − | − | |||||

| Deinococcus proteolyticus | Deinococcus-Thermus | Deinococci | Deinococcales | Deinococcaceae | Deinococcus | − | − | − | − |

In bold the bacteria isolates typical of Lothus corniculatus, in underline those typical of Plantago lanceolata. The isolates were categorized into three groups according to the produced amount: +low concentrations (<1 µg/ml), ++moderate concentrations (1–2.99 µg/ml) and +++high concentrations (>3 µg/ml).

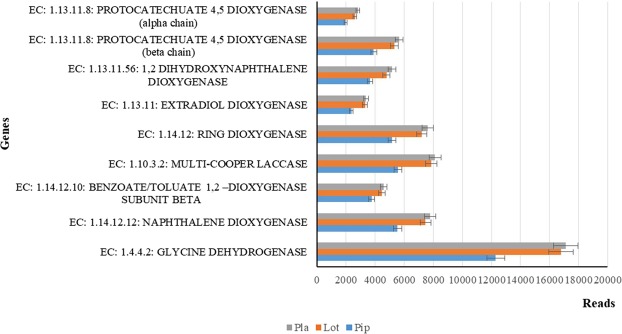

Functional analyses of PAH degrading genes

The reads and fragments (in million) produced in three different rhizosphere soils are: 0.45 M of fragments and 0.91 M of reads in Piptatherum miliaceum, 0.57 M of fragments and 1.15 M of reads in Lothus corniculatus, 0.57 M of fragments and 1.14 M of reads in Plantago lanceolata. In contrast with the heterogeneity of the taxonomy of bacteria structure (82%) in three different rhizosphere soils, there are important alterations in the abundance of the genes encoding enzymes for PAHs degradation (Fig. 8). Our results showed a high gene abundance of several oxidoreductases involved in PAH metabolism, as a test of the PAH degradation potential by native soil microorganisms11,49–51. In fact, the dioxygenase family genes (naphthalene 1,2-dioxygenase, extradiol dioxygenase, benzoate 1,2 dioxygenase, protocatechuate 4,5-dioxygenase (alpha and beta chain) and 1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene dioxygenase) are the most abundant in PHAs contaminated soils, particularly in rhizosphere soil of Plantago lanceolata as compared to Piptatherum miliaceum and Lothus corniculatus (Fig. 8). Therefore, from our data, it is possible to hypothesize different ways of degradation of the PAHs, although all could start by an initial oxidation by laccases followed the activity of dioxygenases and decarboxylases, helping the ulterior degradation of PAHs; hypothesizing that natural soil bacterial populations are able to use specific enzymes and common pathways to degrade PAHs.

Figure 8.

Genes for degrading PAHs from soil metagenomes of Piptatherum miliaceum [Pip], Lothus corniculatus [Lot], Plantago lanceolata [Pla].

Conclusions

Our obtained data showed that PAHs contamination at the Bagnoli brownfield site (Southern Italy) is relevant and its origin is mainly due to the industrial activities and processes that had been working for decades. Almost the 44% of the soil samples in the industrial district were contaminated by PAHs with 4, 5, and 6 ring. Media contents of ∑PAHs in the soil were higher than the maximum permitted concentrations for residential/recreational land use, as it represent the remediation objective stated by Italian Government for Bagnoli site recovery. All PAHs congeners overcomed the recommended limits for corresponding soil categories and BghiP, BaP and IP mainly control pollution. Analysis of diagnostic ratios showed that petroleum and coal combustion were the main sources of PAHs in the investigated site. The studied uptake by native plants indicates that PAHs root accumulation is promoted and movement to the aboveground biomass (translocation) is limited. Interesting PAHs roots accumulation rate were observed for several native species. Based on our results, plant PAHs concentration levels mainly depend on rhizosphere soil PAHs content and type of plant species. Maximum PAHs root accumulation was found in monocotyledons Poaceae such as Pip and Fes. These type of plants are known to have a fibrous root system with several moderately branching roots growing from the stem. While, a taproot system is common in dicotyledons. Monocots fibrous root system consisting of a mass of similarly sized roots that maximizes absorption. Boyle and Shann52 showed that also microbial activity was higher in monocot rhizosphere soils than dicot ones soils and demonstrated that monocot rhizosphere soil degraded many organic contaminants faster than dicot soils. Piptatherum miliaceum (L.) Coss on has suitable attributes such as rapid growth and high root cover and stimulates soil microbial communities24. Besides, our data indicated that Rhizoremediation process involve both plants and their associated rhizosphere microbes. Various microbes include as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Pseudomonas fluoresens, Mycobacterium spp., Rhodococcus spp., Paenibaciluus spp. are involved in PAHs degradation48,53. Our bacteria that for about 85% belong to the phylum of Proteobacteria in general have a marked propensity to the endophytic habitat. This is very important both for determining the performance of the plant and for the degrading activity of their rhizosphere34. Functional metagenomics showed that the abundance of genes degrading PAHs is present in three rhizosphere soils, confirming the metabolic potential of PAHs-degrading microorganisms present into contaminated soil, and assuming a possible ways of degradation PAHs in contaminated soils11,12. The root-exudates help the activity of the microbes, which respond to the exudate, buffet rapidly during the bioremediation of soils. This is in concordance with previous works in which it was markedly noted a strong rhizosphere effect on degradation of PAHs through the stimulation of indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, exopolysaccharides and ammonia. Our data show that PAHs pollution selects a specific rhizosphere microflora that degrades and helps the plant to adapt better and therefore to high performance. Therefore, these results can lead to innovative biotechnological applications in bioremediation processes in the field. In conclusion, our results demonstrated that the microbe-assisted phytoremediation was found to be the most advantageous approach obtaining high rates of degradation of PAHs in relation to other strategies, demonstrating that Piptatherum miliaceum, Lothus corniculatus and Plantago lanceolata association could be an environmentally sound management approach for the treatment of aged PAH-polluted soils.

Materials and Methods

Site description and sampling

The Bagnoli brownfield area (2 km2; situated in correspondence of Phlegrean Fields between 40°49′30″91 and 40°47′30″North, and 14°9′30″ and 14°12′0″ East) falls into the western part of the city of Naples (Campania region), Southern Italy. This industrial district was one of the most important integrated steelworks in Italy during the last century until its closure in the nineties due to economic and environmental reasons. Because of industrial activities, large amount and types of contaminants were generated and dispersed throughout the whole area. The sampling campaign was conducted during 2017 with the identification of 76 areas characterized by high concentrations of PAHs in which the dominant plant species were identified. The most represented species are shown in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Materials). Roots and leaves of each species were gathered and stored in sterile polypropylene tubes. Rhizosphere soil samples of the above plants were also gathered and stored in polypropylene tubes and kept at 4 °C for further analysis. All analysis were performed in triplicate.

Soil and plant (roots and leaves) PAHs analyses

The analysis of PAHs comprised of 13PAHs and followed the procedure US-EPA method 8270D. The target analytics (Table 3) were extracted by an accelerated solvent extractor, purified using a silica gel column, and detected by a gas chromatograph (7890 A, Agilent, USA) coupled with a mass spectrometer (5977B, Agilent, USA). Deuterated fluorene, Deuterated fenanthrene, Deuterated chrysene and Deuterated perylene were added to the samples prior to extraction, and were considered as internal standards for quantification of the 13 PAHs as described by the USEPA54.

Table 3.

List of PAHs analysed and their abbreviations, also used in the text and figures.

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons PAHs | Abbreviation | Molecular weight (g/mol) | N° of rings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrysene | Chr | 228 | 4 |

| Pyrene | Pyr | 202 | 4 |

| Benzo[a]anthracene | BaA | 228 | 5 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | BaP | 252 | 5 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | BbF | 252 | 5 |

| Benzo[k]fluorantene | BkF | 252 | 5 |

| Dibenzo[a,h]anthracene | DahA | 278 | 5 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | BghiP | 276 | 6 |

| Indeno [1,2,3-c,d] pyrene | IP | 276 | 6 |

| Dibenzo[a,e]pyrene | DaeP | 302 | 6 |

| Dibenzo[a,h]pyrene | Dahp | 302 | 6 |

| Dibenzo[a,i]pyrene | DaiP | 302 | 6 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | DalP | 302 | 6 |

The number of rings and molecular weights are also reported.

At every 20 samples were enclosed the determination of a certified reference material (Beechwood (PCP and PAH) BCR® certified Reference Material- Sigma-Aldrich, Italy) such as quality control. Blanks and matrices plus standard addition (a mixture of 13 EPA PAHs and 4 Deuterated PAHs) were quantified sporadically to determine the accuracy of the testing. Procedural blanks were quantified sporadically to evaluate the cross-contamination. In the blank controls the PAHs elements were under the limits of detection.

Soil PAHs fingerprint

Since PAHs emission profile for a given origin can be conditioned by the processes producing the PAHs55, diagnostic ratios are a largely used to apportion the origin of PAHs. According to previous reports56–58 the ratios of BaA/(BaA + Chr) and IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) have been adopted. Because very low proportions of BaA or IP are rarely observed in combustion samples, a BaA/(BaA + Chr) or IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) ratio less than about 0.20 likely indicates natural petroleum-related source. A BaA/(BaA + Chr) ratio value from 0.20 to 0.35 indicate petroleum combustion and >0.35 imply biomass and coal combustion. Literature values suggest biomass and coal combustion for a IcdP/(IcdP + BghiP) ratio above 0.50. While, combustion products of gasoline, kerosene, diesel and crude oil all have ratios below 0.50, with vehicle emissions falling between 0.24 and 0.40.

Selection of the native bacteria

The rhizosphere soils were selected of three species of three different families that showed high uptake of PAHs: Piptatherum miliaceum (L.) Coss. (Poaceae)[Pip], Lothus corniculatus L. (Fabaceae) [Lot], Plantago lanceolata L. (Plantaginaceae) [Pla]. For the selection, 1 g of homogenized rhizosphere soil was incubated in duplicate in 50 ml of a mineral medium at pH 6.8 with the addition of 5% of a mixture of PAHs (EPA 610 Polynuclear Aromatic Hydrocarbons Mixture, Sigma- Aldrich, Milan Italy)10.

Brief as described in Guarino et al.10, cultures were incubated in 250 ml of a mineral medium in conical flasks at 28 °C in an orbital shaker (200 rpm) for five days. Then, to isolate the greatest number of strains, 100 ml of serial tenfold dilutions of bacterial cultures were propagated on two different solid media: LB and R2A (Sigma-Aldrich, Milan Italy) for to not overlook slower growing colonies. First colonies were visualized after 4 days of incubation at 28 °C and after other five days, a total count of colonies was performed10. For each rhizosphere soil have been obtained and preserved fifty-one colonies per medium and per samples were randomly selected and maintained as pure cultures10.

Molecular identification of native isolated strains of bacteria

Two grams of rhizosphere soil of three species of three different families were used for the isolation of genomic DNA using the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories Inc., USA) from following the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracted DNA preparations were quantified and quality checked using a Nanodrop 1000 Spectrophotometer. Universal eubacterial primers (F27a: AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG; R1492a: GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT) were used as template for16S rRNA gene amplification. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed with GoTaq® Polymerase (Promega) according to the supplier’s instructions. PCR-amplified DNA was sequenced with a BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems Inc. USA) using an automated DNA sequencer (ABI model 3500 Genetic Analyzer). Nucleotide sequences were edited and assembled with Lasergene version 11.2.1 (DNASTAR®) and subjected to homology comparison (BLAST analysis) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) server (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi)10.

In vitro tests for plant growth promoting (PGP) traits

The bacteria strains were analysed for Plant Growth Promoting activities (PGP). Indolacetic acid (IAA) production, siderophores release, exopolysaccharides (EPSs) production and ammonia production were determined as described by Guarino et al.10.

Library preparation and sequencing PHAs degrading genes

‘Nugen Ovation Ultralow System V2′ kit (Nugen, San Carlos, CA) was used for library preparation. The samples were quantified and quality tested using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Libraries were processed and sequenced on MiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA), pair-end with 300 cycles per read. Base calling and demultiplexing were performed on instrument. Analysis were focused on the genes involved Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation as KEGG elements reported in a recent work11. Gene sequences were downloaded from Uniprot, and the short reads obtained from the sequencing experiments were blasted against the above-mentioned genes using BLASTX v2.2.29. All reads resulting in a hit with an e-value lower than 0.1 were retained for analysis.

Statistical data analyses

Univariate statistical analyses were performed to show the single-element distribution. The data below the instrumental detection limit (IDL) were assigned a value corresponding to 50% of the detection limit59. The Pearson correlation coefficients between PAHs concentrations in plants and rhizosphere soils were calculated. The statistical significance of the results was verified at the significance level of alpha < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Author Contributions

C.G. and R.S. wrote the main manuscript text. D.Z. wrote the analysis statistic. M.M., B.C. and G.B. prepared figures. L.M., D.B., D.G., E.R.S. and D.C. prepared the site Bagnoli.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48005-7.

References

- 1.Stogiannidis E, Laane R. Source characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by using their molecular indices: an overview of possibilities. Reviews of Environmental Contamination Toxicology. 2015;234:49–133. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10638-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lasota J, Blońska E. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Content in Contaminated Forest Soils with Different Humus Types. Water Air Soil Pollution. 2018;229(6):204–212. doi: 10.1007/s11270-018-3857-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maliszewska-Kordybach B, Smreczak B, Klimkowicz-Pawlas A, Terelak H. Monitoring of the total content of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in arable soils in Poland. Chemosphere. 2008;73:1284–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aichner B, Bussian BM, Lehnik-Habrink P, Hein S. Regionalized concentrations and fingerprints of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in German forest soils. Environmental Pollution. 2015;203:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trellua C, et al. Characteristics of PAH tar oil contaminated soils—Black particles,resins and implications for treatment strategies. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2017;327:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartley W, Dickinson NM, Riby P, Shutes B. Sustainable ecological restoration of brownfield sites through engineering or managed natural attenuation? A case study from Northwest England. Ecological Engineering. 2012;40:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2011.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green L. Evaluating predictors for brownfield redevelopment. Land Use Policy. 2018;73:299–319. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang C, Wu S, Zhou S, Shi Y, Song J. Characteristics and Source Identification of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Urban Soils: A Review. Pedosphere. 2017;27(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60293-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vivo, B. & Lima, A. The Bagnoli-Napoli Brownfield Site in Italy: Before and After the Remediation. Environmental Geochemistry (Second Edition): Site Characterization, Data Analysis and Case Histories. Elsevier 389–416 (2018).

- 10.Guarino C, Spada V, Sciarrillo R. Assessment of three approaches of bioremediation (Natural Attenuation, Landfarming and Bioagumentation—Assistited Landfarming) for a petroleum hydrocarbons contaminated soil. Chemosphere. 2017;170:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zafra G, Absalón ÁE, Anducho-Reyes MÁ, Fernandez FJ, Cortés-Espinosa DV. Construction of PAH-degrading mixed microbial consortia by induced selection in soil. Chemosphere. 2017;172:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crampona M, Bodilisb J, Portet-Koltalo F. Linking initial soil bacterial diversity and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) degradation potential. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2018;359:500–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin F, et al. Betaproteobacteria dominance and diversity shifts in the bacterial community of a PAH-contaminated soil exposed to phenanthrene. Environmental Pollution. 2012;162:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Núñez EV, et al. Modifications of bacterial populations in anthracene contaminated soil. Applied Soil Ecology. 2012;61:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2012.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niepceron M, et al. GammaProteobacteria as a potential bioindicator of a multiple contamination by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in agricultural soils. Environmental Pollution. 2013;180:99–205. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeon CO, Park W, Ghiorse WC, Madsen EL. Polaromonas naphthalenivorans sp. nov., a naphthalene-degrading bacterium from naphthalene-contaminated sediment. International Journal Systematic Evolutionary and Microbiology. 2004;54:93–97. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez-Gines MJ, Hernández AJ, Pérez-Leblic M, Pastor J, Vangronsveld J. Phytoremediation of soils co-contaminated by organic compounds and heavy metals: Bioassays with Lupinus luteus L. and associated endophytic bacteria. Journal of Environmental Management. 2014;143C:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarino C, et al. Identification of native-metal tolerant plant species in situ: Environmental implications and functional traits. Science of the Total Environment. 2019;650:3156–3167. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang FX, Chen DS, Gao YZ, Zhang Y. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in subcellular root tissues of ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam.) BMC Plant Biology. 2010;10(1):210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiou C, Sheng G, Manes M. A partition-limited model for the plant uptake of organic contaminants from soil and water. Environmental Science & Technology. 2001;35(7):1437–44. doi: 10.1021/es0017561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin H, Tao S, Zuo Q, Coveney RM. Uptake of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by maize plants. Environmental Pollution. 2007;148:614–619. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavalcanti TG, et al. Seed Options For Toxicity Tests In Soils Contaminated With Oil. Canadian Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences. 2016;10(3):4039–4045. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dourado R, et al. Determination of Microbial Contaminants Recovered From Brazilian Petrol Stations. Revista Mexicana de Ingeniería Química. 2017;16(3):983–990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno-Barriga F, et al. Organic matter dynamics, soil aggregation and microbial biomass and activity in Technosols created with metalliferous mine residues, biochar and marble waste. Geoderma. 2017;301:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2017.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandowe BAM, et al. Plant diversity enhances the natural attenuation of polycyclic aromatic compounds (PAHs and oxygenated PAHs) in grassland soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2019;129:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fismes J, Perrin-Ganier C, Empereur-Bissonnet P, Morel JL. Soil-to-root transfer and translocation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by vegetables grown on industrial contaminated soils. Journal Environmental Quality. 2002;31(5):1649–1656. doi: 10.2134/jeq2002.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolattukudy PE. Biopolyester membranes of plants: Cutin and suberin. Science. 1980;208:990–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.208.4447.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Briggs GG, Bromilow RH, Evans AA. Relationships between lipophilicity and root uptake and translocation of non ionised chemicals by barley. Pesticide Science. 1982;13:495–504. doi: 10.1002/ps.2780130506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwab AP, Al-Assi AA, Banks MK. Adsorption of naphtalene onto plant roots. Journal Environmental Quality. 1998;27:220–224. doi: 10.2134/jeq1998.00472425002700010031x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galazka A, et al. Genetic and Functional Diversity of Bacterial Microbiome in Soils with Long Term Impacts of Petroleum Hydrocarbons. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018;9:1923. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartmann M, Widmer F. Community structure analysis are more sensitive to differences in soil bacterial communities than anonymous diversity indices. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2006;72:7804–7812. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01464-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng L, Qiao M, Arp HPH. Phytoremediation efficiency of a PAH-contaminated industrial soil using ryegrass, white clover, and celery as mono- and mixed cultures. Journal of Soils and Sediments. 2011;11:482–490. doi: 10.1007/s11368-010-0319-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galazka A, Galazka R. Phytoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils artificially polluted using plant-associated-endophytic bacteria and Dactylis glomerata as the bioremediation plant. Polish Journal Microbiology. 2015;64:241–252. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0009.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santoyoa G, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, del Carmen Orozco-Mosqueda M, Glick BR. Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes. Microbiological Research. 2016;183:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Y, Cheng Z, Glick BR. The presence of a1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase deletion mutation alters the physiology of the endophytic plant growth-promoting bacterium Burkholderia phytofirmans PsJN. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2009;296:131–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Romero FM, Pieckenstain MM. The communities of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) leaf endophytic bacteria, analyzed by 16S-ribosomalRNA gene pyrosequencing. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2014;351:187–194. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marquez-Santacruz HA, Hernandez-Leon R, Orozco-Mosqueda MC, Velazquez-Sepulveda I, Santoyo G. Diversity of bacterial endophytes in roots of Mexican husk tomato plants (Physalis ixocarpa) and their detection in the rhizosphere. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2010;9:2372–2380. doi: 10.4238/vol9-4gmr921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Y, Yang H, Zhang T, Sun J, Lou K. Illumina-based analysis of endophytic bacterial diversity and space-time dynamics in sugar beet on the north slope of Tianshan mountain. Applied Microbiology Biotechnology. 2014;98:6375–6385. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5720-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doong RA, Lei WG. Solubilization and mineralization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Pseudomonas putida in the presence of surfactant. Journal Hazardous Materials. 2003;96:15–27. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3894(02)00167-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Z, Selvam A, Wong JW. Effects of rhamnolipids on cell surface hydrophobicityof PAH degrading bacteria and the biodegradation of phenanthrene. Bioresource Technology. 2011;102:3999–4007. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuleva B, Christova N, Jordanov B. Naphthalene degradation and biosurfactant activity by Bacillus cereus 28BN. Z Naturforsch C. 2005;60:577–582. doi: 10.1515/znc-2005-7-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mordukhova EA, Sokolov SL, Kochetkov VV. Involvement of naphthalene dioxygenase in indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis by Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2000;190:279–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cavalcanti TG, et al. Use of Agro-Industrial Waste in the Removal of Phenanthrene and Pyrene by Microbial Consortia in Soil. Waste and Biomass Valorization. 2019;10:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s12649-017-0041-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Komaniecka I, et al. Occurrence of an unusual hopanoid-containing lipid A among lipopolysaccharides from Bradyrhizobium species. Journal Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(51):35644–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.614529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Juhasz AL, Naidu R. Bioremediation of high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: a review of the microbial degradation of benzo[α]pyrene. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 2000;45:57–88. doi: 10.1016/S0964-8305(00)00052-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaidya S, Jain K, Madamwar D. Metabolism of pyrene through phthalic acid pathway by enriched bacterial consortium composed of Pseudomonas, Burkholderia, and Rhodococcus (PBR) Biotechnology. 2017;7(1):29. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0598-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dasgupta D, Jublee J, Suparna M. Characterization, phylogenetic distribution and evolutionary trajectories of diverse hydrocarbon degrading microorganisms isolated from refinery sludge. Biotechnology. 2018;8:273. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oberai M, Khanna V. Rhizoremediation – Plant Microbe Interactions in the Removal of Pollutants. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2018;7(1):2280–2287. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2018.701.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chemerys A, et al. Characterization of novel polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon dioxygenases from the bacterial metagenomic DNA of a contaminated soil. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2014;80:6591–6600. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01883-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loviso CL, et al. Metagenomics reveals the high polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-degradation potential of abundant uncultured bacteria from chronically polluted subantarctic and temperate coastal marine environments. Journal Applied Microbiology. 2015;119:411–424. doi: 10.1111/jam.12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma B, Lyu XF, Zha T, He Y, Xu JM. Reconstructed metagenomes reveal changes of microbial functional profiling during PAH degradation along a rice (Oryza sativa) rhizosphere gradient. Journal Applied Microbiology. 2015;118:890–900. doi: 10.1111/jam.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyle JJ, Shann J. Biodegradation of Phenol, 2,4-DCP, 2,4-D, and 2,4,5-T in Field-Collected Rhizosphere and Nonrhizosphere Soils. Journal of Environmental Quality. 1995;24:132–142. doi: 10.2134/jeq1995.00472425002400040033x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bisht S, et al. Bioremediation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) using rhizosphere technology. Brazilian Journal Microbialogy. 2015;46:7–21. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838246120131354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.USEPA, Method 3540C, test methods for evaluating solid waste, physically chemical methods. SW-846 annual. US Environ. Protect. Agency. Revision3 (1996a).

- 55.Manoli E, Kouras A, Samara C. Profile analysis of ambient and source emitted particle-bound polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from three sites in northern Greece. Chemosphere. 2004;56:867–878. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo-Li Y, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils of the central Tibetan Plateau, China: Distribution, sources, transport and contribution in global cycling. Environmental Pollution. 2015;203:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thiombane M, et al. Source patterns and contamination level of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban and rural areas of Southern Italian soils. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2018;25(26):26361–26382. doi: 10.1007/s10653-018-0147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu S, et al. Sources, influencing factors and environmental indications of PAH pollution in urban soil columns of Shanghai, China. Ecological Indicators. 2018;85:1170–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.11.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reimann, C., Filzmoser, P., Garrett, R. & Dutter, R. Statistical Data Analysis Explained: Applied Environmental Statistics with R. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, England (2008).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.