Abstract

This study was conducted to estimate the current prevalence of hypertension, cardiovascular condition and hearing difficulty of workers exposure to occupational noise, and to analyze any associations between these abnormal signs and occupational noise exposure. The subjects included 5205 noise-exposed workers. Workers with high noise exposure were more likely to have a higher threshold value than low exposure ones (P < 0.05). Subjects in the high exposure group had a significantly higher risk of hypertension and hearing loss than the ones in low exposure group. Between the ages of 30 and 45, high-level occupational noise exposure led to a significantly raising risk of both hypertension (Adjusted OR = 1.59, 95% CI, 1.19–2.11) and hearing loss (Adjusted OR = 1.28, 95% CI, 1.03–1.60) when comparing to low-level noise exposure. In male workers, the prevalence of hearing difficulty in high exposure group was approximately 1.2 times worse than in low group (P = 0.006). In addition, exposure to high noise level demonstrated a significant association with hypertension and hearing loss when the duration time to occupational noise was longer than 10 years. Hypertension and hearing difficulty is more prevalent in the noise-exposed group (higher than 85 dB[A]). Steps to reduce workplace noise levels and to improve workplace-based health are thus urgently needed.

Subject terms: Occupational health, Epidemiology

Introduction

Exposure to occupational noise in relation to occupational injuries has become a legitimate public health issue in recent years. In addition to incurring adverse effects on the auditory system, noise, as a stressor and one of the most harmful agents for workers, may also cause elevated blood pressure, anxiety, angiocardiopathy, and impaired hormone secretion1–4. Many studies suggest that along with hearing difficulty, noise exposure has been especially associated with cardiovascular diseases such as arteriosclerosis, hypertension, and coronary heart disease5–8. The pathway from noise exposure to these clinical features has been thought to cascade through the autonomic nervous system and endocrine system by a stress response which motivates some biological risk factors for cardiovascular disease (for instance blood pressure and serum lipids)9. Despite the above findings, work by other researchers could not find any association between noise exposure and health effects; thus, a consensus concerning this issue is still lacking.10–13.

In order to observe whether there is in indeed an association between noise exposure and abnormal health effects such as hypertension, cardiovascular condition or hearing loss, we undertook this study and analyzed data from occupational, physical examinations performed in the Nanjing Prevention and Treatment Center for Occupational Diseases from 2016 to 2017.

Using occupational, physical examination data, the purposes of this study were the following: (1) estimate the current prevalence of hypertension, cardiovascular condition, and hearing difficulty with workers who have been exposed themselves to occupational noise for many years; (2) examine any link these outcomes may have to occupational noise exposure.

Materials and Methods

Study population and settings

In this cross-sectional study, we initially recruited 6048 workers with occupational exposure to noise who received both a physical test and assessment in the Nanjing Prevention and Treatment Center for Occupational Diseases. To avoid interference and difficulty in the statistical analysis, those who declined to participate, gave incomplete information about occupational exposure to noise, or did not complete the physical examination report, were excluded from the current research. Subsequently, a total of 843 workers were excluded.

In order to examine the association between occupational noise exposure and health condition, we divided the participants into a high exposure group and a low exposure group and selected 85 dB(A) (the specific domestic noise levels in working places) as the cut-off value for the different noise-exposure groups. Subjects whose exposure level of working noise was less than 85 dB(A) were placed into the low-level group, while those whose exposure was higher than 85 dB(A) were placed into the high-level group. The subjects in high exposure group were selected without any restriction in age or gender. Those in low-exposure group corresponded to subjects in high-exposure group via frequency-matching (1:4) which considered factors of age, exposure time, and sex, and selected individuals from the same company who were having medical examination from the same hospital at the same time. Finally, the study group comprised 5205 noise-exposed workers (1041 high exposure and 4174 low exposure) from factories in Nanjing city.

Health assessment

Industrial hygienist used a questionnaire for each subject to collected information by face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire obtained personal information including age, length of working years, and history of occupational noise exposure. Health status was evaluated in all subjects by clinical and laboratory examination, which was performed after a face-to-face interview. In their assessment, these health and physical examinations used signs, pulse, blood pressure (BP), electrocardiogram, Ultrasonic B, blood routine, and hepatic function tests.

Audiometry and noise exposure assessment

According to the Chinese national criteria for measuring noise exposure in the real workplace (GBZ/T 189.8–2007), a sound pressure individual audiometer should be used to evaluate the real working environment. In our study, noise exposure levels were assessed with a sound pressure individual audiometer (Noise-Pro, Quest, USA) at regular time in the day at selected workplaces for three consecutive days twice a year. In order to evaluate the actual noise exposure level, the results were converted to equivalent continuous A-weighted sound pressure from a nominal eight-hours working day (Lex.8 h).

Tone audiometry was conducted by use of the Beckesy audiometer. All subjects underwent a tonal audiometric examination that was performed by an experienced physician. Hearing tests were operated after a period of at least fourteen hours without noise exposure. On the basis of diagnostic criteria (GB 49–2014), both left and right ears were tested by a method of ascending pure tones at frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000, 3000, 4000 and 6000 Hz. Both ears’ high-frequency threshold in average (BHFTA) was calculated as follows:

BHFTA: Both ears’ high-frequency threshold on average; unit is dB.

HLL: Sum threshold of 3000 Hz, 4000 Hz and 6000 Hz of left ear; unit is dB.

HLR: Sum threshold of 3000 Hz, 4000 Hz and 6000 Hz of right ear; unit is dB.

Outcome variables

Blood pressure (BP) was measured according to the standardized WHO method (World Health Organization, 1983). After resting for at least 15 minutes, the subjects were placed in the sitting position during blood pressure measurement. In each subject, two measurements were made and the mean results of the two measurements have been used to represent individuals’ final blood pressure in our study. If the two test results differed by more than 4 mmHg in either systolic blood pressure (SBP) or diastolic blood pressure (DBP), measurements were repeated after a further 10-minute rest until the difference conformed to this criterion. Subjects were diagnosed as hypertension if they reported a previous medical diagnosis of hypertension, or if their mean SBP was higher than 140 mmHg, or if their mean DBP was higher than 90 mmHg.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) results having no disorder according to relevant doctors or health professionals were considered “normal,” and all the others were defined as “abnormal.”

Workers whose BHFTA worse than 25 dB were defined as high-frequency hearing loss, while those less than 25 dB were defined as normal.

Ethical considerations

This project has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Prevention and Treatment Center for Occupational Diseases. All of the participants received a clear explanation of study purposes and procedures and signed informed consents. Ethical considerations have been respected throughout the entire study period.

Statistical analysis

We used a computerized database (SAS 9.1.3) to analyze all of the data. Continuous data were evaluated using univariate analysis of variance and Student’s t-tests, and qualitative data were analyzed by Pearson χ2 contingency tables. We used multivariate logistic regression analysis, calculating crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), to test the level of association between noise exposure and health conditions by controlling potential confounding factors that included age, gender, exposure time to occupational noise and so on. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

General characteristics of the subjects

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the subjects who were exposed to occupational noise. There are 5205 subjects who were exposed to workplace noise accepted physical examinations. There were 4164 workers exposed to the low noise level, and 1041 exposed to the high noise level. Of the subjects included, 93.76% were male, and 6.24% were female. The mean age was 37.23 ± 9.11 years, and the mean exposure time to noise was 5.31 ± 5.28 years. There was no significant difference between the low and high noise exposure individuals regarding age, gender and exposure time to noise (Table 1). However, subjects with high noise exposure have a higher threshold value than the low exposure ones (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of low and high workplace noise exposure subjects.

| Variable | All (N = 5205) | High exposure level (N = 1041) | Low exposure level (N = 4164) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 4880 | 93.76 | 976 | 93.76 | 3904 | 93.76 | 1.000a |

| Female | 325 | 6.24 | 65 | 6.24 | 260 | 6.24 | |

| Age, years | 37.23 ± 9.11 | 37.06 ± 9.20 | 37.27 ± 9.09 | 0.500b | |||

| <30 | 1292 | 24.82 | 263 | 25.26 | 1029 | 24.71 | 0.502a |

| 30–45 | 2638 | 50.68 | 532 | 51.10 | 2106 | 50.58 | |

| >45 | 1275 | 24.50 | 246 | 23.63 | 1029 | 24.71 | |

| Exposure time, years | 5.31 ± 5.28 | 5.25 ± 5.17 | 5.33 ± 5.32 | 0.680b | |||

| <3 | 1996 | 38.35 | 402 | 38.62 | 1594 | 38.28 | 0.231a |

| 3–10 | 2325 | 44.67 | 484 | 46.49 | 1841 | 44.21 | |

| >10 | 884 | 16.98 | 155 | 14.89 | 729 | 17.51 | |

| Threshold [dB (A)] | 23.32 ± 10.50 | 23.53 ± 10.12 | 22.48 ± 11.87 | 0.004 b | |||

aTwo-sided χ2 test for the frequency distributions of selected variables between low and high exposure level.

bt-test of the difference between the two exposure groups.

Prevalence of abnormal cardiovascular conditions and hearing difficulty

As can be seen from Table 2, the prevalence of each condition in all participants was as follows: hypertension 11.83%, abnormal ECG 13.20%, and hearing difficulty 22.23%. In the group exposed to a high noise level, the prevalence of hypertension, abnormal ECG, and hearing difficulty was 13.64%, 13.74%, and 25.74% respectively. Meanwhile, in the low noise group, the above prevalence was 11.38%, 13.06% and, 21.35% respectively. We may infer that workers in the high exposure group had significantly higher risks of hypertension and hearing loss than workers who were exposed to a lower noise level; P value was 0.047 for hypertension and 0.003 for hearing loss. However, there was no significant difference when concerning the distribution of ECG between the two exposure groups (P = 0.573).

Table 2.

Cardiovascular and hearing conditions of the two exposure groups.

| Variable | All (N = 5205) | High exposure level (N = 1041) | Low exposure level (N = 4164) | P a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Hypertension | Without | 4589 | 88.17 | 899 | 86.36 | 3690 | 88.62 | 0.047 |

| With | 616 | 11.83 | 142 | 13.64 | 474 | 11.38 | ||

| ECG | Normal | 4518 | 86.80 | 898 | 86.26 | 3620 | 86.94 | 0.573 |

| Abnormal | 687 | 13.20 | 143 | 13.74 | 544 | 13.06 | ||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 4048 | 77.77 | 773 | 74.26 | 3275 | 78.65 | 0.003 |

| With | 1157 | 22.23 | 268 | 25.74 | 889 | 21.35 | ||

aTwo-sided χ2 test for the frequency distributions of selected variables between low and high exposure level.

Stratified analysis between the two exposure groups by age

We divided age into three stages (<30, 30–45, and >45). For ages between 30 and 45, a history of high-level occupational noise exposure led to a significantly raising dangerous of both hypertension (Crude OR = 1.56, 95% CI, 1.18–2.07) and hearing loss (Crude OR = 1.26, 95% CI, 1.01–1.58) when comparing to low-level noise exposure, after adjustment for sex and exposure time to occupational noise; the Adjusted OR and 95% CI was 1.59 (1.19–2.11) and 1.28 (1.03–1.60) respectively. However, the difference was not statistically significant when the analysis was limited to those under the age of 30 and over the age of 45 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Stratified analysis of cardiovascular and hearing conditions between two exposure groups by age.

| Variable | High exposure level N (%) | Low exposure levelc N (%) | P valuea | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 years | ||||||

| Hypertension | Without | 254 (96.58) | 984 (95.63) | 0.605 | 0.78 (0.37–1.61) | 0.78 (0.37–1.61) |

| With | 9 (3.42) | 45 (4.37) | ||||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 227 (86.31) | 927 (90.09) | 0.093 | 1.44 (0.96–2.17) | 1.43 (0.95–2.16) |

| With | 36 (13.69) | 102 (9.91) | ||||

| 30–45 years | ||||||

| Hypertension | Without | 456 (85.71) | 1903 (90.36) | 0.003 | 1.56 (1.18–2.07) | 1.59 (1.19–2.11) |

| With | 76 (14.29) | 203 (9.64) | ||||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 396 (74.44) | 1656 (78.63) | 0.041 | 1.26 (1.01–1.58) | 1.28 (1.03–1.60) |

| With | 136 (25.56) | 450 (21.37) | ||||

| >45 years | ||||||

| Hypertension | Without | 189 (76.83) | 803 (78.04) | 0.670 | 1.07 (0.77–1.49) | 1.08 (0.77–1.50) |

| With | 57 (23.17) | 226 (21.96) | ||||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 150 (60.98) | 692 (67.25) | 0.072 | 1.31 (0.99–1.75) | 1.32 (0.98–1.77) |

| With | 96 (39.02) | 337 (32.75) | ||||

aTwo-sided χ2 test for comparing the distribution of hypertension, abnormal ECG and hearing loss between two groups.

bAdjusted for sex and occupational exposure time for noise in the logistic regression model.

cReference group.

Stratified analysis between the two exposure groups by gender

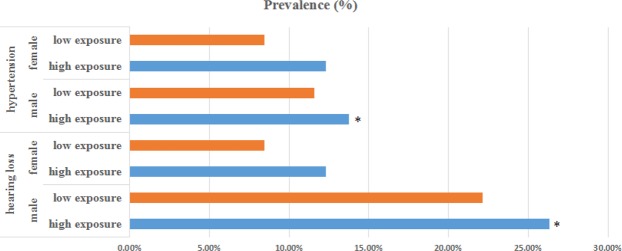

We analyzed associations of health conditions and occupational noise level versus gender. In female workers, there was no association of the prevalence of hypertension or hearing loss with occupational noise exposure. Yet, significant differences were found in males between these two exposure levels. Figure 1 shows that in the male workers, the prevalence of hearing difficulty in the low exposure group was 22.13%, while in the high exposure group it was 26.33%, which was 1.2 higher, and statistically different from the low exposure group (P = 0.006). In addition, the risk of hypertension in high exposure group was worse than low exposure group (Adjusted OR = 1.25, 95% CI, 1.01–1.54). These results indicate a distinct effect of high-level occupational noise on health conditions according to subjects’ gender.

Figure 1.

Bar charts for the prevalence of both hearing loss and hypertension in subjects. The participants were divided by gender. Orange bars represent low exposure subjects, and blue bars represent high exposure subjects. The gender is indicated on the left of each bar. An asterisk indicates that a significant effect (P < 0.05) was found for that gender.

Stratified analysis between the two exposure groups by occupational duration to noise

After stratifying by duration time to occupational noise, we divided subjects into three categories (<3, 3–10, and >10 years). Exposure to high noise level demonstrated a significant association with hypertension and hearing loss when duration time to occupational noise was longer than 10 years (Table 4). In an analysis of the longest duration group (>10 years), the prevalence of hypertension showed a significant difference between the high exposure level and the low exposure level group (P = 0.010); the risk of hypertension in high group was about 1.69 times higher than in low group (Adjusted OR = 1.69, 95% CI, 1.11–2.56). Similar results also occurred in the distribution of hearing loss, which showed that the incidence of hearing loss in high exposure group was statistically different from that in low exposure group (P < 0.000); the prevalence of hearing loss in high exposure group was 57.42%, which was approximately twice higher than in low exposure group (Adjusted OR = 3.60, 95% CI, 2.51–5.16). However, in regard to a duration time of fewer than 10 years, there were no significant difference between the two exposure groups.

Table 4.

Stratified analysis of cardiovascular and hearing conditions between the two exposure groups by occupational duration for noise.

| Variable | High exposure levelv N (%) | Low exposure levelc N (%) | P valuea | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3 years | ||||||

| Hypertension | Without | 362 (90.05) | 1434 (89.96) | 1.000 | 0.99 (0.69–1.43) | 0.99 (0.68–1.44) |

| With | 40 (9.95) | 160 (10.04) | ||||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 335 (83.33) | 1293 (81.12) | 0.349 | 0.86 (0.64–1.15) | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) |

| With | 67 (16.67) | 301 (18.88) | ||||

| 3–10 years | ||||||

| Hypertension | Without | 421 (86.98) | 1644 (89.30) | 0.168 | 1.25 (0.92–1.69) | 1.31 (0.97–1.79) |

| With | 63 (13.02) | 197 (10.70) | ||||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 372 (76.86) | 1449 (78.71) | 0.386 | 1.11 (0.88–1.41) | 1.15 (0.90–1.47) |

| With | 112 (23.14) | 392 (21.29) | ||||

| >10 years | ||||||

| Hypertension | Without | 116 (74.84) | 612 (83.95) | 0.010 | 1.76 (1.16–2.66) | 1.69 (1.11–2.56) |

| With | 39 (25.16) | 117 (16.05) | ||||

| Hearing Loss | Without | 66 (42.58) | 533 (73.11) | 0.000 | 3.67 (2.56–5.25) | 3.60 (2.51–5.16) |

| With | 89 (57.42) | 196 (26.89) | ||||

aTwo-sided χ2 test for comparing the rate of hypertension, abnormal ECG, and hearing loss between the two groups.

bAdjusted for sex and occupational exposure time for noise in the logistic regression model.

cReference group.

Discussion

This study reported the prevalence of hypertension, abnormal ECG, and abnormal hearing thresholds in workers exposed to occupational noise in Nanjing city. Furthermore, we assessed the association between noise exposure and the incidence of hypertension, abnormal ECG, and hearing loss. We found that subjects exposed to intense ambient noise (high noise level) had significantly higher dangers of hypertension and hearing loss than subjects who were exposed to a lower noise level (P < 0.05). The risks of hypertension and hearing loss were elevated especially in male workers whose ages were between 30 and 45 years, or whose exposure times were longer than 10 years.

Noise as a kind of psychosocial stressor may cause hypertension through activating sympathetic nervous systems and the hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis, which may motivate sequential elevated levels of adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol14–17. Unfortunately, these three hormones also regulate blood pressure18,19. In addition, Ghotbi M. R. et al. had shown that the level of stress hormones, especially catecholamine significantly increased with noise exposure increment15. And some researchers had found that catestatin may inhibit the sympathetic activation in hypertension, and may involve in the pathogenesis of hypertension20,21. In regards to occupational noise levels above 85 dB(A), the association between noise exposure and hypertension is inconsistent. Some researchers have showed that occupational noise exposure is associated with a higher risk of hypertension or with a sustained elevation of blood pressure1,2,22,23, which is consistent with our findings (Table 2). Still, other studies have not suggested any significant link11,24,25. The difference between these results may be attributed to the different usage of personal protective equipment among different workers who exposed to high-frequency noise. Hence, we need to choose outer-ear measurements of noise levels alone as a source of exposure bias because they do not influence the true intensity of inner-ear exposure.

A number of epidemiological studies have demonstrated that high-frequency hearing loss is resulted from occupational noise exposure26–30. Chang suggests that, in aircraft-manufacturing workers, high-frequency hearing loss is a good biomarker for long occupational noise exposure31, which shows a trend similar to our research. Table 3 illustrates how a exposure of high-level occupational noise resulted in a significantly elevated risk of hearing loss especially for workers between the ages of 30 and 45. It should be emphasized that aging is the most common reason for sensorineural and noise-induced hearing abnormalities, and both related closely with the formation of ROS (reactive oxygen species). Researchers suggested that hearing damage is associated with the outer hair cell apoptosis pathway which due to oxidative stress involving oxidative damage to biological molecular (such as nucleic acids, lipids, proteins and so on) and accompanies progression of several physical conditions, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, eproductive and kidney diseases, and also different cancers32.

Participants were grouped by noise exposure duration and tested for associations in separate groups, we found that a significant association of hearing loss and hypertension with high-frequency noise in the group whose exposure time was longer than 10 years (Table 4). Also, in one industrial-based study, workers with abnormal audiograms had significantly longer noise exposure time relative to those with normal audiograms (P < 0.001)33. These results indicate that the risk of hearing loss or hypertension will be even worse when workers are exposed to higher occupational noise and for a longer duration. However, this is not unexpected because higher level of occupational noise and longer duration will be more dangerous, consequently, a more significant impact would be anticipated.

No significant association was measured between noise exposure levels and ECG conditions. This may be due to a lack of representative sample size, or other unknown environmental factors. Whatever the cause, whether high noise levels contribute to abnormal ECG is a question which remains unclarified.

There were several limitations to our study. A cross-sectional analysis showing a temporal problem might astrict the evidence for a causal relationship between occupational noise and unhealthy condition. However, the causal association between noise exposure and hearing abnormality has been acknowledged34,35. The variable of duration to occupation noise was based on own oral-report which could have led to bias, as workers may not have remembered clearly or could have potentially given false information about longer exposure time. Additionally, several potential confounders are known to cause hypertension or other cardiovascular diseases were not considered as covariates in our study, including a family history of hypertension, lack of exercise, and poor nutrition in daily diet36–38. Given that these are also risk factors for cardiovascular disorders, the true prevalence and association between noise exposure and health condition may be more significant than estimated in this study.

Protecting noise-exposed workers by reducing noise exposure in work places and improving safeguard procedures will be very important for preventing noise-induced hearing loss and other physiological abnormalities. Noise-exposed workers need to wear earplugs or earmuffs correctly. Worksite health programs including monitoring hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases should also focus on noise-exposed workers. Those who are identified in screening to have hypertension, hearing loss or abnormal ECG should be advised to change to a different work post which has less or no noise exposure.

Finally, although this study contributed several significant results towards the correlation between occupational noise and cardiovascular disorders, as well as hearing conditions, further human and animal studies are needed to explore the exact nature and basic mechanism for this association.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participant in our present study, in addition to the Jiangsu Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (JSCDC) for being our cooperating organization. This study was supported by Jiangsu Provincial Medical Youth Talent (QNRC2016127), the Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation, the Nanjing Department of Health (ZKX17050), and the Jiangsu Provincial Medical Innovation Team (CXTDA2017029).

Author Contributions

X.L. performed the information collection and wrote the paper. Q.D. and B.W. worked for physical examination. H.S. and S.W. analyzed the data. B.Z. designed the whole research.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiuting Li, Qiu Dong and Boshen Wang contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Shizhi Wang, Email: shizhiwang2009@seu.edu.cn.

Baoli Zhu, Email: zhubl@jscdc.cn.

References

- 1.Dehghan H, Bastami MT, Mahaki B. Evaluating combined effect of noise and heat on blood pressure changes among males in climatic chamber[J] J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:39. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_107_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomei G, et al. Occupational exposure to noise and the cardiovascular system: a meta-analysis[J] Sci Total Environ. 2010;408(4):681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alimohammadi I, Sandrock S, Gohari MR. The effects of low frequency noise on mental performance and annoyance[J] Environ Monit Assess. 2013;185(8):7043–7051. doi: 10.1007/s10661-013-3084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu SY, Lee CL, Lin KY, Lin YH. Noise and stress effects on preschool personnel[J] Noise Health. 2012;14(59):166–178. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.99892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dzhambov AM, Dimitrova DD. Residential road traffic noise as a risk factor for hypertension in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of analytic studies published in the period 2011–2017[J] Environ Pollut. 2018;240:306–318. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu S Y, Lee C L, Lin K Y, Lin Y H. The acute effect of exposure to noise on cardiovascular parameters in young adults[J]. J Occup Health (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Eriksson HP, et al. Longitudinal study of occupational noise exposure and joint effects with job strain and risk for coronary heart disease and stroke in Swedish men[J] BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e19160. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan WQ, Moline J, Kim H, Mannino DM. Exposure to loud noise, bilateral high-frequency hearing loss and coronary heart disease[J] Occup Environ Med. 2016;73(1):34–41. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basner M, et al. Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health[J] Lancet. 2014;383(9925):1325–1332. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61613-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokholm ZA, et al. Recent and long-term occupational noise exposure and salivary cortisol level[J] Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan WQ, Mannino DM. Occupational Noise Exposure, Bilateral High-Frequency Hearing Loss, and Blood Pressure[J] J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(5):462–468. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halonen JI, et al. Associations of traffic noise with self-rated health and psychotropic medication use[J] Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(3):235–243. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engdahl B, Aarhus L, Lie A, Tambs K. Cardiovascular risk factors and hearing loss: The HUNT study[J] Int J Audiol. 2015;54(12):958–966. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2015.1090631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pouryaghoub G, Mehrdad R, Valipouri A. Effect of Acute Noise Exposure on Salivary Cortisol: A Randomized Controlled Trial[J] Acta Med Iran. 2016;54(10):657–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghotbi MR, et al. Changes in urinary catecholamines in response to noise exposure in workers at Sarcheshmeh Copper Complex, Kerman, Iran[J] Environ Monit Assess. 2013;185(11):8809–8814. doi: 10.1007/s10661-013-3213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Said MA, El-Gohary OA. Effect of noise stress on cardiovascular system in adult male albino rat: implication of stress hormones, endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress[J] Gen Physiol Biophys. 2016;35(3):371–377. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaghoubi, K. et al. The effect of occupational noise exposure on systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and salivary cortisol level among automotive assembly workers[J]. Int J Occup Saf Ergon, 1–6 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ngan KW, Lee SW, Ng FF, Tan PE, Khaw KS. Randomized double-blinded comparison of norepinephrine and phenylephrine for maintenance of blood pressure during spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery[J] Anesthesiology. 2015;122(4):736–745. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barebring L, O’Connell M, Winkvist A, Johannsson G, Augustin H. Serum cortisol and vitamin D status are independently associated with blood pressure in pregnancy[J] J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;189:259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg T. alpha2-Adrenoreceptor Constraint of Catecholamine Release and Blood Pressure Is Enhanced in Female Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats[J] Front Neurosci. 2016;10:130. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson A, et al. Diabetes and Hypertension Differentially Affect Renal Catecholamines and Renal Reactive Oxygen Species[J] Front Physiol. 2019;10:309. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Yang D, Fan W, Fan C, Wu G. Cardiovascular risk factors in noise-exposed workers in china: Small area study[J] Noise Health. 2017;19(91):245–253. doi: 10.4103/nah.NAH_56_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attarchi M, Golabadi M, Labbafinejad Y, Mohammadi S. Combined effects of exposure to occupational noise and mixed organic solvents on blood pressure in car manufacturing company workers[J] Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(2):243–251. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stokholm ZA, Bonde JP, Christensen KL, Hansen AM, Kolstad HA. Occupational noise exposure and the risk of hypertension[J] Epidemiology. 2013;24(1):135–142. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b7f76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zamanian Z, et al. Investigation of the effect of occupational noise exposure on blood pressure and heart rate of steel industry workers[J] J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:256060. doi: 10.1155/2013/256060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macca I, et al. High-frequency hearing thresholds: effects of age, occupational ultrasound and noise exposure[J] Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(2):197–211. doi: 10.1007/s00420-014-0951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawlaczyk-Luszczynska M, Zamojska-Daniszewska M, Dudarewicz A, Zaborowski K. Exposure to excessive sounds and hearing status in academic classical music students[J] Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017;30(1):55–75.. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pouryaghoub G, Mehrdad R, Pourhosein S. Noise-Induced hearing loss among professional musicians[J] J Occup Health. 2017;59(1):33–37. doi: 10.1539/joh.16-0217-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alabdulwahhab BM, et al. Hearing loss and its association with occupational noise exposure among Saudi dentists: a cross-sectional study[J] BDJ Open. 2016;2:16006. doi: 10.1038/bdjopen.2016.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pourbakht A, Imani A. The protective effect of conditioning on noise-induced hearing loss is frequency-dependent[J] Acta Med Iran. 2012;50(10):664–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang TY, et al. High-frequency hearing loss, occupational noise exposure and hypertension: a cross-sectional study in male workers[J] Environ Health. 2011;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sisto R, et al. Oxidative stress biomarkers and otoacoustic emissions in humans exposed to styrene and noise[J] Int J Audiol. 2016;55(9):523–531. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1177215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelegrin AC, Canuet L, Rodriguez AA, Morales MP. Predictive factors of occupational noise-induced hearing loss in Spanish workers: A prospective study[J] Noise Health. 2015;17(78):343–349. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.165064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masilamani R, Rasib A, Darus A, Ting AS. Noise-induced hearing loss and associated factors among vector control workers in a Malaysian state[J] Asia Pac J Public Health. 2014;26(6):642–650. doi: 10.1177/1010539512444776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen H, et al. A functional Ser326Cys polymorphism in hOGG1 is associated with noise-induced hearing loss in a Chinese population[J] Plos One. 2014;9(3):e89662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viera AJ. Hypertension Update: Current Guidelines[J] FP Essent. 2018;469:11–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Challa, H. J., Uppaluri, K. R. DASH Diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension)[J] (2018).

- 38.Koohkan S, Potz A, Berg A. [Food intake and hypertension–the role of protein quality for reducing of blood pressure][J] MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156(14):65–66. doi: 10.1007/s15006-014-3346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]