Abstract

Background

To assess the comparative efficacy and safety of first-line immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK).

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and major international scientific meetings were searched for relevant randomized controlled trials. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were the primary outcomes and serious adverse events (SAEs) were the secondary outcome of interests and were reported as hazard ratio (HR) or odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Fourteen trials with 9,570 patients randomized to receive ten ICI-based treatments (including PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 antibodies and PD-1/PD-L1 with CTLA-4 combination therapies) were included in the meta-analysis. Pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy (Pem + CT) (HR =0.56, 95% CI: 0.42–0.74) and Pem (HR =0.75, 95% CI: 0.62–0.91) were more effective than CT in terms of OS; Pem + CT was also superior to Pem (HR =0.74, 95% CI: 0.56–0.98), atezolizumab + CT (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.50–0.85), ipilimumab + CT (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.47–0.89), and nivolumab (HR =0.52, 95% CI: 0.31–0.87). In subgroup analyses, Pem + CT was more effective than CT regardless of PD-L1 expression, while Pem was superior to CT only for PD-L1 with expression ≥50%; Pem + CT showed significant OS advantage over other treatments in patients with non-squamous cell carcinoma (NSCC); ICIs had a comparable efficacy in younger vs. older patients. Based on treatment ranking in terms of OS, Pem + CT had the highest probability (98%) of being the most effective treatment, followed by Pem (70%), with acceptable toxicity limit.

Conclusions

Pem + CT seemed to be more effective first-line regimen for advanced NSCLC with wild-type EGFR or ALK, especially for patients with NSCC. However, limitations of the study including methodological quality and immature OS data need to be considered.

Keywords: Advanced non-small cell lung cancer (advanced NSCLC), immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), first-line treatment, network meta-analysis (NMA)

Introduction

Traditionally, the first-line standard of care for previously untreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been the platinum-based combination chemotherapy (CT). However, treatment strategies have changed greatly in recent years with the development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Currently, targeted therapy is the standard first-line treatment for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) positive patients. However, only 15–50% of patients with NSCLC have an activating EGFR mutation (1), and ALK translocations occur in 2–20% of patients (2-4).

For advanced NSCLC with wild-type EGFR or ALK, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) of anti-programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) [pembrolizumab (Pem) or nivolumab (Niv)] and its ligand PD-L1 [atezolizumab (Ate) or durvalumab (Dur)] antibodies, either as monotherapy or in combination with CT, have been recently demonstrated to be more effective when compared to standard CT (5-20). Moreover, ICIs of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) antibodies [ipilimumab (Ipi) or tremelimumab (Tre)] (21,22) and combination therapy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies (Niv + Ipi or Dur + Tre) (13,14,20) have also shown promising efficacy in a cohort of patients. However, direct comparison of trials between these ICI-based treatments is still lacking, and therefore, there are still unresolved questions on which first-line regimen is optimal for this population.

In light of these critical issues, we performed a network meta-analysis (NMA) to assess the comparative effectiveness and tolerability of all ICI-based treatments, which could result in the identification of the preferred first-line regimen in advanced NSCLC patients with wild-type EGFR or ALK.

Methods

Literature search strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) criteria (23) (Table S1). PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and other major international scientific meetings (American Society of Clinical Oncology, European Society for Medical Oncology, and World Conference on Lung Cancer) were searched for available studies published before March 1, 2019, using the strategies shown in Table S2. The reference lists of retrieved studies were manually looked over for relevant additional studies which were omitted by the electronic search.

Table S1. PRISMA NMA checklist of items to include when reporting a systematic review involving a network meta-analysis.

| Section/topic | Item # | Checklist item | Reported on page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review incorporating a network meta-analysis (or related form of meta-analysis) | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary including, as applicable: | 1 |

| Background: main objectives | |||

| Methods: data sources; study eligibility criteria, participants, and interventions; study appraisal; and synthesis methods, such as network meta-analysis | |||

| Results: number of studies and participants identified; summary estimates with corresponding confidence/credible intervals; treatment rankings may also be discussed. Authors may choose to summarize pairwise comparisons against a chosen treatment included in their analyses for brevity | |||

| Discussion/conclusions: limitations; conclusions and implications of findings | |||

| Other: primary source of funding; systematic review registration number with registry name | |||

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known, including mention of why a network meta-analysis has been conducted | 2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of questions being addressed, with reference to participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, and study design (PICOS) | 2 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists and if and where it can be accessed (e.g., Web address); and, if available, provide registration information, including registration number | NA |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify study characteristics (e.g., PICOS, length of follow-up) and report characteristics (e.g., years considered, language, publication status) used as criteria for eligibility, giving rationale. Clearly describe eligible treatments included in the treatment network, and note whether any have been clustered or merged into the same node (with justification) |

2 |

| Information sources | 7 | Describe all information sources (e.g., databases with dates of coverage, contact with study authors to identify additional studies) in the search and date last searched | 2 |

| Search | 8 | Present full electronic search strategy for at least one database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated | 2 |

| Study selection | 9 | State the process for selecting studies (i.e., screening, eligibility, included in systematic review, and, if applicable, included in the meta-analysis) | 2 |

| Data collection process | 10 | Describe method of data extraction from reports (e.g., piloted forms, independently, in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators | 2 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought (e.g., PICOS, funding sources) and any assumptions and simplifications made | 2 |

| Geometry of the network | S1 | Describe methods used to explore the geometry of the treatment network under study and potential biases related to it. This should include how the evidence base has been graphically summarized for presentation, and what characteristics were compiled and used to describe the evidence base to readers | 2 |

| Risk of bias within individual studies | 12 | Describe methods used for assessing risk of bias of individual studies (including specification of whether this was done at the study or outcome level), and how this information is to be used in any data synthesis |

2 |

| Summary measures | 13 | State the principal summary measures (e.g., risk ratio, difference in means). Also describe the use of additional summary measures assessed, such as treatment rankings and surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) values, as well as modified approaches used to present summary findings from meta-analyses | 2–3 |

| Planned methods of analysis | 14 | Describe the methods of handling data and combining results of studies for each network meta-analysis. This should include, but not be limited to: | 2–3 |

| Handling of multi-arm trials | |||

| Selection of variance structure | |||

| Selection of prior distributions in Bayesian analyses; and | |||

| Assessment of model fit | |||

| Assessment of inconsistency | S2 | Describe the statistical methods used to evaluate the agreement of direct and indirect evidence in the treatment network(s) studied. Describe efforts taken to address its presence when found | 2–3 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 15 | Specify any assessment of risk of bias that may affect the cumulative evidence (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting within studies) | 2–3 |

| Additional analyses | 16 | Describe methods of additional analyses if done, indicating which were pre-specified. This may include, but not be limited to, the following: | 3 |

| Sensitivity or subgroup analyses | |||

| Meta-regression analyses | |||

| Alternative formulations of the treatment network; and | |||

| Use of alternative prior distributions for Bayesian analyses (if applicable) | |||

| Results† | |||

| Study selection | 17 | Give numbers of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally with a flow diagram | 3 |

| Presentation of network structure | S3 | Provide a network graph of the included studies to enable visualization of the geometry of the treatment network | 6 |

| Summary of network geometry | S4 | Provide a brief overview of characteristics of the treatment network. This may include commentary on the abundance of trials and randomized patients for the different interventions and pairwise comparisons in the network, gaps of evidence in the treatment network, and potential biases reflected by the network structure | 3 |

| Study characteristics | 18 | For each study, present characteristics for which data were extracted (e.g., study size, PICOS, follow-up period) and provide the citations | 4 |

| Risk of bias within studies | 19 | Present data on risk of bias of each study and, if available, any outcome level assessment | 3 |

| Results of individual studies | 20 | For all outcomes considered (benefits or harms), present, for each study: (I) simple summary data for each intervention group, and (II) effect estimates and confidence intervals. Modified approaches may be needed to deal with information from larger networks | 3–4 |

| Synthesis of results | 21 | Present results of each meta-analysis done, including confidence/credible intervals. In larger networks, authors may focus on comparisons versus a particular comparator (e.g., placebo or standard care), with full findings presented in an appendix. League tables and forest plots may be considered to summarize pairwise comparisons. If additional summary measures were explored (such as treatment rankings), these should also be presented | 5 |

| Exploration for inconsistency | S5 | Describe results from investigations of inconsistency. This may include such information as measures of model fit to compare consistency and inconsistency models, P values from statistical tests, or summary of inconsistency estimates from different parts of the treatment network | 6 |

| Risk of bias across studies | 22 | Present results of any assessment of risk of bias across studies for the evidence base being studied | 3 |

| Results of additional analyses | 23 | Give results of additional analyses, if done (e.g., sensitivity or subgroup analyses, meta-regression analyses, alternative network geometries studied, alternative choice of prior distributions for Bayesian analyses, and so forth) | 7–10 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 24 | Summarize the main findings, including the strength of evidence for each main outcome; consider their relevance to key groups (e.g., healthcare providers, users, and policy-makers) | 8,11,12 |

| Limitations | 25 | Discuss limitations at study and outcome level (e.g., risk of bias), and at review level (e.g., incomplete retrieval of identified research, reporting bias). Comment on the validity of the assumptions, such as transitivity and consistency. Comment on any concerns regarding network geometry (e.g., avoidance of certain comparisons) | 12 |

| Conclusions | 26 | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence, and implications for future research | 12 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 27 | Describe sources of funding for the systematic review and other support (e.g., supply of data); role of funders for the systematic review. This should also include information regarding whether funding has been received from manufacturers of treatments in the network and/or whether some of the authors are content experts with professional conflicts of interest that could affect use of treatments in the network |

NA |

†, authors may wish to plan for use of appendices to present all relevant information in full detail for items in this section. PICOS, population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, study design; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis; NMA, network meta-analysis.

Table S2. Search strategy.

| # | Query |

|---|---|

| Search strategy in PubMed | |

| #1 | “Lung Neoplasms”[mh] |

| #2 | Lung Neoplasms[tiab] OR Neoplasms, Lung[tiab] OR Lung Neoplasm[tiab] OR Neoplasm, Lung[tiab] OR Neoplasms, Pulmonary[tiab] OR Neoplasm, Pulmonary[tiab] OR Pulmonary Neoplasm[tiab] OR Pulmonary Neoplasms[tiab] OR Lung Cancer[tiab] OR Cancer, Lung[tiab] OR Cancers, Lung[tiab] OR Lung Cancers[tiab] OR Pulmonary Cancer[tiab] OR Cancer, Pulmonary[tiab] OR Cancers, Pulmonary[tiab] OR Pulmonary Cancers[tiab] OR Cancer of the Lung[tiab] OR Cancer of Lung[tiab] |

| #3 | “Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung”[mh] |

| #4 | Carcinoma, Non Small Cell Lung[tiab] OR Carcinomas, Non-Small-Cell Lung[tiab] OR Lung Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell[tiab] OR Lung Carcinomas, Non-Small-Cell[tiab] OR Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinomas[tiab] OR Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer[tiab] OR Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma[tiab] OR Non Small Cell Lung Carcinoma[tiab] OR Carcinoma, Non-Small Cell Lung[tiab] OR Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer[tiab] OR NSCLC[tiab] |

| #5 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 |

| #6 | Advanced[tiab] OR Stage IV[tiab] OR Stage 4[tiab] OR Stage four[tiab] OR StageIIIB[tiab] OR Metastatic[tiab] OR Metastases[tiab] |

| #7 | Programmed death ligand 1[tiab] OR PD-L1[tiab] OR Programmed death 1[tiab] OR PD-1[tiab] OR Anti-Programmed death ligand 1[tiab] OR Anti-PD-L1[tiab] OR Anti-Programmed death 1[tiab] OR Anti-PD-1[tiab] OR Atezolizumab[tiab] OR Durvalumab[tiab] OR Nivolumab[tiab] OR Pembrolizumab[tiab] |

| #8 | Anti-Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4[tiab] OR Anti-CTLA-4[tiab] OR Ipilimumab[tiab] OR Tremelimumab[tiab] |

| #9 | Immunotherapy[tiab] OR Immune checkpoint inhibitors[tiab] OR ICI[tiab] |

| #10 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 |

| #11 | First-line[tiab] OR Untreated[tiab] OR Chemotherapy naïve[tiab] OR Frontline[tiab] OR Treatment naïve[tiab] |

| #12 | Randomized Controlled Tial[pt] |

| #13 | Controlled Cinical Trial[pt] |

| #14 | Randomized[tiab] |

| #15 | Placebo[tiab] |

| #16 | Randomly[tiab] |

| #17 #18 |

Trial[tiab] Drug Therapy[sh] |

| #19 | Groups[tiab] |

| #20 | #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 |

| #21 | Animals[mh] |

| #22 | Humans[mh] |

| #23 | #21 NOT #22 |

| #24 | #20 NOT #23 |

| #25 | #5 AND #6 AND #10 AND #11 AND #24 |

| Search strategy in Embase | |

| #1 | ‘lung cancer’/exp |

| #2 | ‘non small cell lung cancer’/exp |

| #3 | ‘non small cell’:ab,ti |

| #4 | ‘nsclc’:ti,ab |

| #5 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 |

| #6 | ‘advanced’:ab,ti OR ‘stage IV’:ab,ti OR ‘stage 4’:ab,ti OR ‘stage four’:ab,ti OR ‘stageIIIB’:ab,ti OR ‘metastatic’:ab,ti OR ‘metastases’:ab,ti |

| #7 | ‘programmed death ligand 1’:ab,ti OR ‘PD-L1’:ab,ti OR ‘programmed death 1’:ab,ti OR ‘PD-1’:ab,ti OR ‘anti-programmed death ligand 1’:ab,ti OR ‘anti–PD-L1’:ab,ti OR ‘anti-programmed death 1’:ab,ti OR ‘anti–PD-1’:ab,ti OR ‘atezolizumab’:ab,ti OR ‘durvalumab’:ab,ti OR ‘nivolumab’:ab,ti OR ‘pembrolizumab’:ab,ti |

| #8 | ‘anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4’:ab,ti OR ‘anti–CTLA-4’:ab,ti OR ‘ipilimumab’:ab,ti OR ‘tremelimumab’:ab,ti |

| #9 | ‘immunotherapy’:ab,ti OR ‘immune checkpoint inhibitors’:ab,ti OR ‘ICI’:ab,ti |

| #10 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 |

| #11 | ‘first-line’:ab,ti OR ‘untreated’:ab,ti OR ‘chemotherapy naïve’:ab,ti OR ‘frontline’:ab,ti OR ‘treatment naïve’:ab,ti |

| #12 | ‘trial’:ab,ti |

| #13 | ‘random*’:ab,ti |

| #14 | ‘clinical trial’/de OR ‘controlled clinical trial’/de OR ‘randomized controlled trial’/de |

| #15 | #12 OR #13 OR #14 |

| #16 | #5 And #6 And #10 And #11 And #15 |

| Search strategy in Cochrane Library | |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung] explode all trees |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Lung Neoplasms] explode all trees |

| #3 | ((lung OR pulmon*) AND (neoplas* OR cancer OR carcinoma* OR tumour* or tumor*)) |

| #4 | non-small cell* |

| #5 | non small cell* |

| #6 | nonsmall cell* |

| #7 | Nsclc |

| #8 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 |

| #9 | (advanced OR stage IV OR stage 4 OR stage four OR stageIIIB OR metastatic OR metastases):ti,ab |

| #10 | (programmed death ligand 1 OR PD-L1 OR programmed death 1 OR PD-1 OR anti-programmed death ligand 1 OR anti-PD-L1 OR anti-programmed death 1 OR anti–PD-1 OR atezolizumab OR durvalumab OR nivolumab OR pembrolizumab):ti,ab |

| #11 | (anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 OR anti-CTLA-4 OR ipilimumab OR tremelimumab):ti,ab |

| #12 | (immunotherapy OR immune checkpoint inhibitors OR ICI):ti,ab |

| #13 | #10 OR #11 OR #12 |

| #14 | (first-line OR untreated OR chemotherapy naïve OR frontline OR treatment naïve):ti,ab |

| #15 | #8 AND #9 AND #13 AND #14 |

| Search strategy in Web of Science | |

| #1 | TS=(“lung cancer” OR “non-small cell lung cancer” OR NSCLC OR ((lung OR pulmon*) AND (neoplas* OR cancer OR carcinoma* OR tumour* or tumor*))) |

| #2 | TS=(“advanced” OR “stage IV” OR “stage 4” OR “stage four” OR “stageIIIB” OR “metastatic” OR “metastases”) |

| #3 | TS=(“programmed death ligand 1” OR “PD-L1 OR programmed death 1” OR “PD-1” OR “anti-programmed death ligand 1” OR “anti-PD-L1” OR “anti-programmed death 1” OR “anti–PD-1” OR “atezolizumab” OR “durvalumab” OR “nivolumab” OR “pembrolizumab”) |

| #4 | TS=(“anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4” OR “anti–CTLA-4” OR “ipilimumab” OR “tremelimumab”) |

| #5 | TS=(“immunotherapy” OR “immune checkpoint inhibitors” OR “ICI”) |

| #6 | #3 OR #4 OR #5 |

| #7 | TS=(“first-line” OR “untreated” OR “chemotherapy naïve” OR “frontline” OR “treatment naïve”) |

| #8 | TS=(“randomized controlled trial” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “clinical trial” OR “random*” OR “rct*” OR “crossover” OR “masked” OR “blind*” OR “placebo*”) |

| #9 | #1 AND #2 AND #6 AND #7 AND #8 |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (I) types of studies: randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (II) types of participants: previously untreated patients with advanced NSCLC with wild-type EGFR or ALK, and patients with squamous NSCLC with unknown status of EGFR or ALK; (III) types of interventions: first-line treatment using one or more ICI-based treatment options for experimental arm and CT for control; and (IV) outcome: reported overall survival (OS) and/or progression-free survival (PFS) data. Studies that failed to meet the above criteria were excluded from the NMA.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted by two independent investigators from each study: first author or name of individual RCT, year of publication, duration of the study, country of origin, treatments, numbers of patients, and data regarding PFS, OS, and serious adverse events (SAEs).

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of RCTs was assessed by Cochrane risk of bias tool (24), which consists of the following five domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data, and selective reporting. An RCT was finally rated as “low risk of bias” (all key domains indicated as low risk), “high risk of bias” (one or more key domains indicated as high risk), and “unclear risk of bias”.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes were OS and PFS, and the secondary outcome was SAEs. Hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used for summary statistics. For direct comparisons, a standard pairwise meta-analysis (PWMA) was performed. A statistical test for heterogeneity was performed using the chi-square (χ2) and I-square (I2) tests with the significance set at I2 >50% or P<0.10. If significant heterogeneity existed, a random-effect analysis model was used; otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used.

Bayesian NMA was performed in a random-effect model using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods (25,26) in JAGS and the GeMTC package in R (https://drugis.org/software/r-packages/gemtc). For each outcome measure, four independent Markov chains were simultaneously run for 20,000 burn-ins and 100,000 inference iterations per chain to obtain the posterior distribution. The traces plot and Brooks-Gelman-Rubin method were used to assess the convergence of the model (27). Treatment effects were estimated by HR/OR and their corresponding 95% CI. Network consistency was assessed with node-split models by statistically testing between direct and indirect estimates within the treatment loop (28). To rank probabilities of all available treatments, the surfaces under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRAs) were calculated (29). SUCRA equals one if the treatment is certain to be the best, and zero if it is certain to be the worst (29). In addition, we conducted subgroup analyses according to histologic type, PD-L1 expression level, and age. Finally, a comparison-adjusted funnel plot was used to detect the presence of small-study effects or publication bias (30).

Results

Literature search results and characteristics of included studies

The literature search results and study selection process are shown in Figure 1. The initial search retrieved a total of 1,430 studies. After removing the duplicates, 687 citations were identified, and 514 of them were excluded through an abstract review. The remaining 173 studies were screened through a full-text review for further inclusion criteria. Finally, 14 RCTs that involved 9,570 patients who received 12 treatments were included in the meta-analysis (5-22). The 12 treatments were as follows: (I) Pem; (II) Pem + CT; (III) Ate + CT; (IV) Ate + bevacizumab + CT (Ate + Bev + CT); (V) Niv; (VI) Niv + CT; (VII) Ipi + CT; (VIII) Niv + Ipi; (IX) Dur; (X) Dur + Tre; (XI) Bev + CT, and (XII) CT. The study characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search and selection. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1. Characteristics of included trials.

| Trial | Design | Time range | Primary endpoint | Treatment details | Sample size | Median follow-up (months) | Median age | Histologic type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEYNOTE-024/2016 (5,6) | III | 2014–2015 | PFS | Pem | 154 | 11.2 | 64.5 | Mixed |

| PP/GP/PC | 151 | 66.0 | ||||||

| KEYNOTE-042/2018 (7) | III | NR | OS | Pem | 637 | 12.8 | 63.0 | Mixed |

| PC/PP | 637 | 63.0 | ||||||

| KEYNOTE-189/2018 (8) | III | 2016–2017 | OS/PFS | Pem + PP | 410 | 10.5 | 65.0 | Non-SCC |

| PP | 206 | 63.5 | ||||||

| KEYNOTE-407/2018 (9) | III | 2016–2017 | OS/PFS | Pem + PC/CnP | 278 | 7.8 | 65.0 | SCC |

| PC/CnP | 281 | 65.0 | ||||||

| KEYNOTE-021/2016 (10,11) | II | 2014–2016 | ORR | Pem + PP | 60 | 10.6 | 62.5 | Non-SCC |

| PP | 63 | 63.2 | ||||||

| CheckMate 026/2017 (12) | III | 2014–2015 | PFS | Niv | 271 | 13.7 | 63.0 | Mixed |

| PP/GP/PC | 270 | 65.0 | ||||||

| CheckMate 227/2018 (13,14) | III | 2015–2016 | PFS/OS | Niv + Ipi | 583 | 11.2 | 64.0 | Mixed |

| Niv + P-based CT | 177 | 64.0 | ||||||

| Niv | 396 | NR | ||||||

| P-based CT | 583 | 64.0 | ||||||

| IMpower150/2018 (15,16) | III | 2015–2016 | PFS/OS | Ate + Bev + PC | 400 | 15.4 | 63.0 | Non-SCC |

| Bev + PC | 400 | 15.5 | 63.0 | |||||

| Ate + PC | 400 | NR | NR | |||||

| IMpower132/2018 (17) | III | NR | PFS/OS | Ate + PP | 292 | 14.8 | 64.0 | Non-SCC |

| PP | 286 | 63.0 | ||||||

| IMpower130/2018 (18) | III | NR | PFS/OS | Ate + CnP | 451 | 19.0 | NR | Non-SCC |

| CnP | 228 | NR | ||||||

| IMpower131/2018 (19) | III | NR | PFS/OS | Ate + CnP | 343 | 17.1 | 65.0 | SCC |

| CnP | 340 | 65.0 | ||||||

| MYSTIC/2018 (20) | III | NR | OS/PFS | Dur + Tre | 163 | NR | NR | Mixed |

| Dur | 163 | NR | ||||||

| P-based CT | 162 | NR | ||||||

| Lynch/2012 (21) | II | 2008–2009 | PFS | Ipi + PC | 21 | NR | NR | SCC |

| PC | 15 | NR | ||||||

| Govindan/2017 (22) | III | 2011–2015 | OS | Ipi + PC | 388 | 12.5 | 64.0 | SCC |

| PC | 361 | 64.0 |

OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; Ate, atezolizumab; Bev, bevacizumab; PC, paclitaxel-carboplatin; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Pem, pembrolizumab; PP, pemetrexed-cisplatin/carboplatin; CnP, paclitaxel-nanoparticle albumin-bound-carboplatin; GP, gemcitabine-cisplatin; Niv, nivolumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; P-based, platinum-based; CT, chemotherapy; Dur, durvalumab; Tre, tremelimumab; NR, not reported.

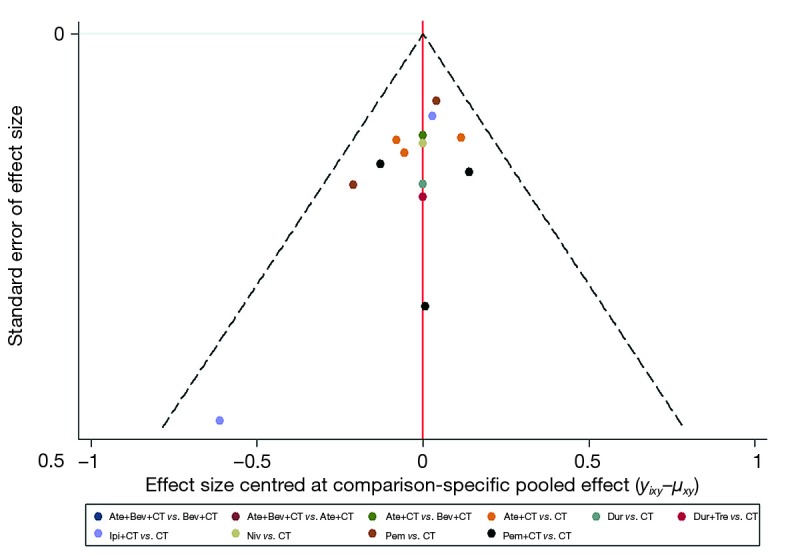

Assessment of included trials

The risk of bias in included RCTs is summarized in Figure S1. Five trials were judged as unclear risk of bias (7,17-20), as they had more than three domains for indicating them an unclear risk. The remaining trials were rated with a low risk of bias. Funnel plot analysis in case of OS did not indicate any evident risk of publication bias (Figure S2).

Figure S1.

Assessment of risk of bias (5-22). (A) Methodological quality graph: authors’ judgment about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies; (B) methodological quality summary: authors’ judgment about each methodological quality item for each included study. “+” low risk of bias; “?” unclear risk of bias; “−” high risk of bias.

Figure S2.

Comparison-adjusted funnel plots of publication bias test for overall survival. Pem, pembrolizumab; Ate, atezolizumab; Bev, bevacizumab; Dur, durvalumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; Niv, nivolumab; Tre, tremelimumab; CT, chemotherapy.

Conventional pairwise meta-analysis

Results of single trial and direct comparison meta-analysis are shown in Table 2. Direct comparison meta-analysis was feasible for Pem + CT vs. CT, Pem vs. CT, Ate + CT vs. CT, Ipi + CT vs. CT, and Niv vs. CT. In case of OS, Pem + CT (HR =0.56, 95% CI: 0.46–0.97, I2 =0%), Pem (HR =0.74, 95% CI: 0.59–0.94, I2 =52%), and Ate + CT (HR =0.86, 95% CI: 0.75–0.97, I2 =0%) showed significant advantage over CT treatment. With regard to PFS, Pem + CT (HR =0.54, 95% CI: 0.46–0.62, I2 =0%), Ate + CT (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.58–0.72, I2 =0%), and Ipi + CT (HR =0.85, 95% CI: 0.74–0.99, I2 =35%) were more effective than CT. As for overall SAEs, Ate + CT was more toxic than CT (OR =1.77, 95% CI: 1.41–2.22, I2 =0%), whereas Pem (OR =0.33, 95% CI: 0.26–0.41, I2 =0%) and Niv (OR =0.30, 95% CI: 0.15–0.57, I2 =85%) showed a significantly lower risk of SAEs when compared to CT.

Table 2. Results of single trial and direct comparison meta-analysis.

| Treatment | Study | OS | PFS | SAEs | Heterogeneity I2 (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (E/C) | HR (95% CI) | N (E/C) | HR (95% CI) | N (E/C) | OR (95% CI) | OS | PFS | SAEs | |||||

| Ate + CT vs. CT | (17-19) | 1,086/854 | 0.86 (0.75–0.97) | 1,086/854 | 0.65 (0.58–0.72) | 1,098/840 | 1.77 (1.41–2.22) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Ipi + CT vs. CT | (21-22) | 409/376 | 0.74 (0.41–1.33) | 409/376 | 0.85 (0.74–0.99) | 388/361 | 2.01 (1.50–2.70)a | 61 | 35 | – | |||

| Pem + CT vs. CT | (8-11) | 748/550 | 0.56 (0.46–0.97) | 748/550 | 0.54 (0.46–0.62) | 742/544 | 1.13 (0.89–1.43) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Niv vs. CT | (12-14) | 271/270 | 1.07 (0.86–1.33)b | 342/349 | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) | 658/833 | 0.30 (0.15–0.57) | – | 0 | 85 | |||

| Pem vs. CT | (5-7) | 791/788 | 0.74 (0.59–0.94) | 791/788 | 0.74 (0.35–1.56) | 790/765 | 0.33 (0.26–0.41) | 52 | 95 | 0 | |||

| Ate + Bev + CT vs. Bev + CT | (15,16) | 359/337 | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) | 359/337 | 0.59 (0.50–0.70) | 393/394 | 1.43 (1.08–1.89) | – | – | – | |||

| Ate + CT vs. Bev + CT | (15,16) | 349/337 | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) | – | – | 400/394 | 0.76 (0.58–1.01) | – | – | – | |||

| Ate + Bev + CT vs. Ate + CT | (15,16) | 359/349 | 0.90 (0.74–1.11) | – | – | 393/394 | 1.82 (1.37–2.42) | – | – | – | |||

| Dur + Tre vs. CT | (20) | 163/162 | 0.85 (0.61–1.17) | 163/162 | 1.05 (0.72–1.53) | 163/162 | 0.55 (0.34–0.90) | – | – | – | |||

| Dur vs. CT | (20) | 163/162 | 0.76 (0.56–1.02) | – | – | 163/162 | 0.34 (0.20–0.58) | – | – | – | |||

| Dur vs. Dur + Tre | (20) | – | – | – | – | 163/163 | 0.61 (0.34–1.08) | – | – | – | |||

| Niv + Ipi vs. Niv | (13,14) | – | – | 101/102 | 0.75 (0.53–1.07) | 576/391 | 1.99 (1.47–2.70) | – | – | – | |||

| Niv + Ipi vs. CT | (13,14) | – | – | 583/583 | 0.83 (0.72–0.96) | 576/570 | 0.81 (0.64–1.04) | – | – | – | |||

| Niv + CT vs. CT | (13,14) | – | – | 117/186 | 0.74 (0.58–0.94) | 172/183 | 1.83 (1.12–3.00) | – | – | – | |||

a, result of reference (22); b, result of reference (12). OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SAEs, serious adverse events; E/C, experimental/control; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ate, atezolizumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; Pem, pembrolizumab; Niv, nivolumab; Bev, bevacizumab; Dur, durvalumab; Tre, tremelimumab; CT, chemotherapy.

NMA

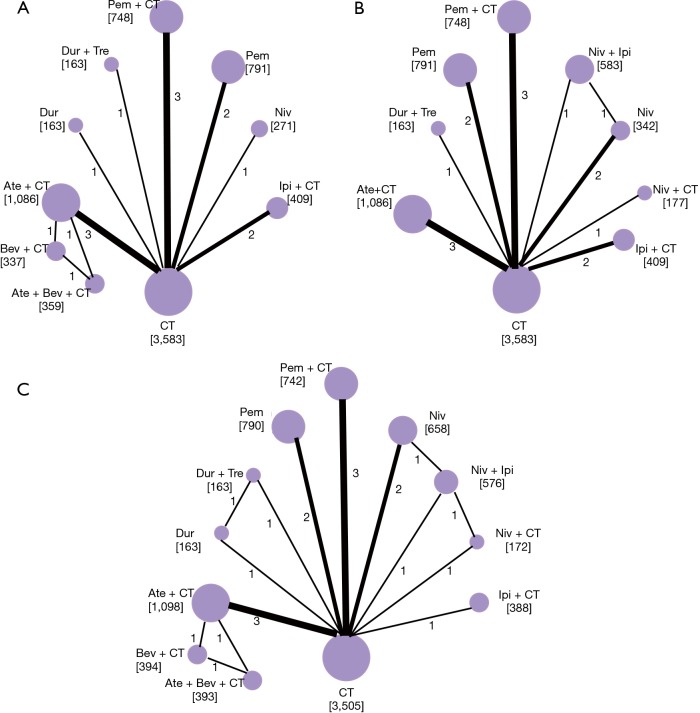

Figure 2 shows the network plot established for NMA for OS and PFS. OS, PFS, and SAE were all reported in 13 trials. Results of the NMA were presented in Figure 3. In terms of OS, Pem + CT (HR =0.56, 95% CI: 0.42–0.74; P<0.001) and Pem (HR =0.75, 95% CI: 0.62–0.91; P=0.004) were more effective than CT; Pem + CT was also superior to Pem (HR =0.74, 95% CI: 0.56–0.98; P=0.036), Ate + CT (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.50–0.85; P=0.002), Ipi + CT (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.47–0.89; P=0.007), and Niv (HR =0.52, 95% CI: 0.31–0.87; P=0.013). With regard to PFS, Pem + CT (HR =0.54, 95% CI: 0.38–0.75; P<0.001) and Ate + CT (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.48–0.88; P=0.005) had a significant advantage over CT; Pem + CT was more effective than Niv (HR =0.49, 95% CI: 0.30–0.82; P=0.007), Niv + Ipi (HR =0.65, 95% CI: 0.43–0.98; P=0.04), and Dur + Tre (HR =0.51, 95% CI: 0.29–0.91; P=0.023); Ate + CT was superior to Niv (HR =0.60, 95% CI: 0.37–0.98; P=0.04). As for overall SAEs, ICIs in combination with CT had generally higher risk of SAEs than ICIs monotherapy; Ate + Bev + CT, Ate + CT, and Ipi + CT were also more toxic than Niv + Ipi, Niv + CT, and Dur + Tre, and Ate + Bev + CT showed significantly higher risk of SAEs than Pem + CT.

Figure 2.

Network of eligible comparisons. (A) overall survival; (B) progression-free survival; (C) serious adverse events. The size of the nodes is proportional to the number of patients (in parentheses) randomized to receive the treatment. The width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials (beside the line) comparing the connected treatments. Pem, pembrolizumab; Ate, atezolizumab; Bev, bevacizumab; Dur, durvalumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; Niv, nivolumab; Tre, tremelimumab; CT, chemotherapy.

Figure 3.

Results of network meta-analysis. OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SAEs, serious adverse events; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Pem, pembrolizumab; Ate, atezolizumab; Bev, bevacizumab; Dur, durvalumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; Niv, nivolumab; Tre, tremelimumab; CT, chemotherapy.

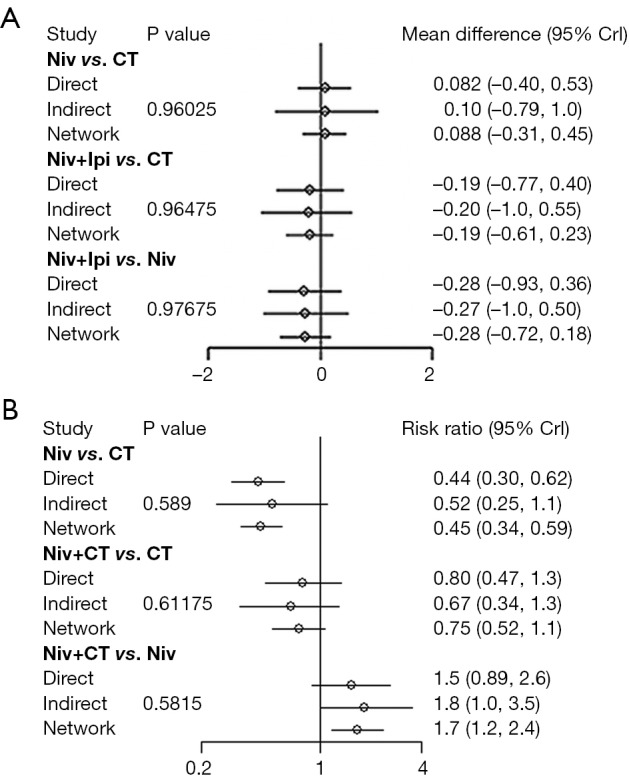

Inconsistency assessment and treatment ranking

There was one independent closed loop in the network for PFS: Niv + Ipi/Niv/CT, and one independent closed loop for SAEs: Niv + CT/Niv/CT. Analysis of inconsistency showed that the NMA results were similar to the PWMA results for the two outcomes, which suggested the consistency between the direct and indirect evidence (Figure S3).

Figure S3.

Inconsistency evaluation by node-splitting analyses. (A) progression-free survival; (B) serious adverse events. Niv, nivolumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; CT, chemotherapy; Crl, credible interval.

Results of the treatment rankings based on SUCRA are shown in Table 3. In terms of OS, Pem + CT (0.98), Pem (0.70), and Ate + Bev + CT (0.67) were ranked the most, second-most, and third-most effective treatments, respectively, followed by Dur (0.65) and Ate + CT (0.49). With regard to PFS, Pem + CT (0.96), Ate + CT (0.80), and Niv + CT (0.62) were ranked the best, second-best, and third-best regimens, respectively, followed by Pem (0.55) and Ipi + CT (0.53). As for SAEs, Niv was ranked as the least toxic regimen (0.07), followed by Dur (0.11) and Pem (0.12); Ate + Bev + CT (0.98) was ranked as the highest toxic regimen.

Table 3. SUCRA values for three outcomes.

| Outcome | Treatment | SUCRA |

|---|---|---|

| OS | Pem + CT | 0.98 |

| Pem | 0.70 | |

| Ate + Bev + CT | 0.67 | |

| Dur | 0.65 | |

| Ate + CT | 0.49 | |

| Dur + Tre | 0.48 | |

| Ipi + CT | 0.47 | |

| Bev + CT | 0.25 | |

| CT | 0.17 | |

| Niv | 0.13 | |

| PFS | Pem + CT | 0.96 |

| Ate + CT | 0.80 | |

| Niv + CT | 0.62 | |

| Pem | 0.55 | |

| Ipi + CT | 0.53 | |

| Niv + Ipi | 0.49 | |

| Dur + Tre | 0.22 | |

| CT | 0.21 | |

| Niv | 0.12 | |

| SAEs | Niv | 0.07 |

| Dur | 0.11 | |

| Pem | 0.12 | |

| Dur + Tre | 0.31 | |

| Niv + CT | 0.36 | |

| Niv + Ipi | 0.41 | |

| CT | 0.55 | |

| Pem + CT | 0.62 | |

| Ate + CT | 0.76 | |

| Ipi + CT | 0.83 | |

| Bev + CT | 0.87 | |

| Ate + Bev + CT | 0.98 |

SUCRA, the surfaces under the cumulative ranking curve; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SAEs, serious adverse events; Pem, pembrolizumab; Ate, atezolizumab; Bev, bevacizumab; Dur, durvalumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; Niv, nivolumab; Tre, tremelimumab; CT, chemotherapy.

Subgroup analyses

Results of subgroup analyses are shown in Figure 4 (SUCRA score is shown in brackets). Subgroup analyses for non-squamous cell carcinoma (NSCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were conducted in 9 trials with 4,683 patients and 8 trials with 2,804 patients, respectively. Patients with NSCC had a significant OS advantage when treated with Pem + CT, Ate + Bev + CT, and Ate + CT compared with CT, and Pem + CT was superior to other ICI-based treatments. Pem + CT, Ate + CT, Pem, and Niv + Ipi were more effective than CT in terms of PFS. For patients with SCC, Pem + CT and Pem were more effective than CT in terms of PFS, but no treatment showed a significant OS advantage over CT.

Figure 4.

Results of subgroup analyses. *, SUCRA score is shown in brackets. OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SAEs, serious adverse events; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Pem, pembrolizumab; Ate, atezolizumab; Bev, bevacizumab; Dur, durvalumab; Ipi, ipilimumab; Niv, nivolumab; CT, chemotherapy.

In the subgroup with ≥50% PD-L1 expression (8 trials with 1,747 patients), Pem + CT and Pem had significant OS and PFS advantage over CT, and Ate + CT was more effective than CT in terms of PFS; Pem + CT was superior to Pem in PFS but not OS. For patients with PD-L1 expression of <50% (7 trials with 3,330 patients), OS advantage over CT was still observed for Pem + CT but not for Pem; Pem + CT, Niv + Ipi, Ate + CT, and Niv + CT had PFS advantage over CT; Pem + CT had a significant OS advantage over Pem. For subgroup of PD-L1 expression 1–49%, Pem + CT showed significant OS (HR =0.56, 95% CI: 0.34–0.93) and PFS (HR =0.56, 95% CI: 0.43–0.73) advantage over CT; Ate + CT was superior to CT in term of PFS (HR =0.70, 95% CI: 0.58–0.84). For patients with PD-L1 expression of <1%, Pem + CT was also more effective than CT either in OS (HR =0.60, 95% CI: 0.43–0.83) or PFS (HR =0.72, 95% CI: 0.50–0.97); Niv + Ipi (HR =0.48, 95% CI: 0.25–0.94) and Ate + CT (HR =0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.86) showed significant PFS advantage over CT.

In case of OS, Pem + CT was superior to CT for both younger (<65 years) (9 trials with 2,877 patients) and older patients (≥65 years) (9 trials with 2,826 patients); Pem showed a significant OS advantage for younger patients and a trend of OS advantage for older patients as well, compared with CT. As for PFS, Pem + CT, Pem, Ate + CT, and Niv + Ipi were more effective than CT in both two groups (younger and older).

Discussion

This novel NMA assessed the comparative efficacy and tolerability of all first-line ICI-based treatments for advanced NSCLC patients with wild-type EGFR or ALK. It showed that Pem + CT seemed to be more effective first-line regimen compared with other ICI-based treatments. Recently, Pem + CT has also demonstrated significant OS advantage over CT alone (8-11). However, no head-to-head comparison between the two regimens is available. In our NMA, Pem + CT showed significant OS advantage over Pem, Ate + CT, Ipi + CT, and Niv. Based on the treatment ranking, Pem + CT had the highest probability of being the most effective treatment in improving OS (98%) and PFS (96%), with similar toxicities to CT. Pem was ranked the second-best regimen for OS with a lower risk of SAEs, when compared to Pem + CT.

Bev has been reported to have immunomodulatory effects through inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor (31-33). However, few studies have investigated whether Bev can enhance the efficacy of ICIs in NSCLC. More recently, a phase III trial evaluated the effect of the combination of Ate, Bev, and CT (ABCP) in patients with metastatic non-squamous NSCLC who had not previously received CT (15,16). Patients in the ABCP group had significantly improved median PFS (8.3 vs. 6.8 months; HR =0.62, 95% CI: 0.52–0.74) and median OS (19.2 vs. 14.7 months; HR =0.78, 95% CI: 0.64–0.96) than patients in the Bev + CT (BCP) group regardless of PD-L1 expression. In the NMA, Ate + Bev + CT showed significant OS advantage over CT. Based on treatment ranking for OS, Ate + Bev + CT was ranked the third-most effective treatment. However, Ate + Bev + CT resulted in a significantly higher risk of SAEs than Pem + CT and Pem and seemed to be the worst tolerated treatment.

Recently, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies combined with CTLA-4 antibodies as the first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC have also been assessed. In MYSTIC trial, first-line Dur + Tre demonstrated clinically meaningful improvement in OS vs. CT in metastatic NSCLC (median OS 16.3 vs. 12.9 months, P=0.036) (20). In another recent phase III trial evaluating Niv + Ipi as first-line treatment in patients with advanced NSCLC (13,14), median PFS was significantly longer with Niv + Ipi than with CT among patients with a high tumor having activating mutations (7.2 vs. 5.5 months; HR =0.84, 95% CI: 0.73–0.98). In addition, Niv + Ipi had better efficacy than Niv monotherapy (7.1 vs. 4.2 months; HR =0.75, 95% CI: 0.53–1.07). However, the two combination regimens did not show OS or PFS advantage over any other treatments in the NMA. Nevertheless, there remains a need of head-to-head comparison between the dual ICIs treatment and other ICI-based regimens in patients with high tumor having activating mutations.

Although ICIs have shown survival improvement in comparison with CT in multiple phase III trials, there are still different and discussed results about the correlation with PD-L1 expression due to the multiple assays used, with different antibodies, and different cut-off value for PD-L1 status. Whether PD-L1 expression is an ideal biomarker to predict the efficacy of ICIs remains debatable. In our NMA, Pem + CT was more effective than CT regardless of PD-L1 expression, while Pem was superior to CT only for PD-L1 with expression ≥50%. The results suggested that either Pem monotherapy or in combination with CT might be considered for patients with PD-L1 expression of ≥50%, while Pem + CT seemed to be a more effective regimen for patients with PD-L1 expression of <50%. Recently, tumor mutational burden (TMB) has also been assessed in NSCLC (34) and appears to be a promising predictive biomarker of the efficacy of ICIs. However, all neoantigens do not have the same effect on tumor immunogenicity, and a high intra-tumor neoantigen heterogeneity may be associated with a shorter PFS with ICIs (35). Thus, the predictive role of TMB for ICIs efficacy still has to be validated in more clinical trials.

Unlike non-squamous NSCLC, there is no particularly effective treatment for patients with advanced squamous NSCLC due to unavailability of approved targeted agents, and platinum-based doublet CT remains the standard first-line treatment. Recently, ICIs have been assessed in advanced squamous NSCLC as the first-line setting, but with inconsistent outcomes. Several phase III trials have shown that first-line treatment of Pem monotherapy or in combination with CT had longer OS or PFS than CT alone for advanced squamous NSCLC (5-7,9). However, no survival benefit was observed from Niv monotherapy, Ate + CT, and Ipi + CT in other phase III trials (12,19,21,22). In our NMA, Pem or Pem + CT was more effective than CT in term of PFS, while no significant difference in OS was observed between CT and any of the ICI-based treatments. Efficacy of ICIs for advanced squamous NSCLC needs further investigation.

ICIs have not been specifically assessed in older patients. Expression of PD-1 was found to be increased in T cells of older adults and its blockade did not restore T cell activity to the same extent as in younger adults (36-38). A meta-analysis in assessing the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies in older patients with metastatic solid tumors showed that PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies had comparable efficacy in younger vs. older patients (39). In our NMA, improvement in survival associated with the use of ICIs was similar between younger and older patients.

Two recent NMAs have also estimated the efficacy of first-line ICIs for advanced NSCLC (40,41) including a study by Frederickson et al. (40) with 27 trials. However, only 7 trials assessed the efficacy of three anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody-based treatments; the remaining trials were those comparing different CT regimens or those comparing CT with Bev + CT. Moreover, most of the patients were with unknown status for targetable mutations. Likewise, in the study of Wang et al. (41), only 9 trials assessing three anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody-based regimens were included. ICIs of CTLA-4 antibodies and combination therapy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies with CTLA-4 antibodies were not assessed in the two studies. In our NMA, 14 RCTs with 10 first-line ICI-based treatments were included, including four anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody-based regimens, two CTLA-4 antibody-based regimens, and two combination therapies of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies with CTLA-4 antibodies. Most of the patients were with wild type EGFR or ALK, and only a few SCC patients were with unknown status for EGFR or ALK. Moreover, we performed subgroup analyses for PD-L1 expression of ≥50% or <50%, squamous/non-squamous, and younger/older patients. Thus, the present NMA would be more comprehensive in assessing the comparative efficacy and tolerability of ICIs, when compared with previously reported meta-analysis (40,41).

There are several limitations in this NMA. First, data were collected and analyzed based on results reported from trials, and not on individual patient data. Second, the diversity of the compared studies in terms of the enrolled population (PD-L1 expression status, histological types, and CT regimens) might lead to heterogeneity and inconsistency, even though subgroup analyses had been performed. Moreover, some included trials reported immature OS data, and the median follow-up for most of the trials was generally short. These limitations do not allow us to reach definitive conclusions about the superiority of one treatment over another. Finally, the toxicity criteria used in some RCTs were not consistent with the others, which would also result in heterogeneity.

Conclusions

Pem + CT seemed to be more effective first-line regimen for advanced NSCLC with wild-type EGFR or ALK, especially for patients with NSCC. However, limitations of the study including methodological quality and immature OS data need to be considered.

Acknowledgments

None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Reck M, Rabe KF. Precision Diagnosis and Treatment for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:849-61. 10.1056/NEJMra1703413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steuer CE, Ramalingam SS. ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer: mechanisms of resistance and emerging treatment options. Cancer 2014;120:2392-402. 10.1002/cncr.28597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Savooji J, Liu D. Second- and third-generation ALK inhibitors for non-small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2016;9:19. 10.1186/s13045-016-0251-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackhall FH, Peters S, Bubendorf L, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcomes for patients with ALK-positive resected stage I to III adenocarcinoma: results from the European Thoracic Oncology Platform Lungscape Project. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2780-7. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. KEYNOTE-024 Investigators Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823-33. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:537-46. 10.1200/JCO.18.00149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes G, Wu YL, Kudaba I, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) versus platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) as first-line therapy for advanced/metastatic NSCLC with a PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥ 1%: open-label, phase 3 KEYNOTE-042 study. Presented at: 2018 ASCO Annu. Meeting. Abstract LBA4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. KEYNOTE-189 Investigators Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2078-92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. KEYNOTE-407 Investigators Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2040-51. 10.1056/NEJMoa1810865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, et al. KEYNOTE-021 investigators Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1497-508. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30498-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borghaei H, Langer CJ, Gadgeel S, et al. 24-Month Overall Survival from KEYNOTE-021 Cohort G: Pemetrexed and Carboplatin with or without Pembrolizumab as First-Line Therapy for Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2019;14:124-9. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. First-Line Nivolumab in Stage IV or Recurrent Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2415-26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1613493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Lung Cancer with a High Tumor Mutational Burden. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2093-104. 10.1056/NEJMoa1801946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borghaei H, Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares LG, et al. Nivolumab (Nivo) + platinum-doublet chemotherapy (chemo) vs chemo as first-line (1L) treatment (Tx) for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with <1% tumor PD-L1 expression: results from CheckMate 227. Presented at: 2018 ASCO Annu. Meeting. Abstract 9001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. IMpower150 Study Group. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2288-301. 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Socinski MA, Jotte R, Cappuzzo F, et al. Impower150: Overall survival (OS) analysis of IMpower150, a randomized Ph 3 study of atezolizumab (atezo)+chemotherapy (chemo)±bevacizumab (bev) vs chemo+bev in 1L nonsquamous (NSQ) NSCLC. Presented at: 2018 ASCO Annu. Meeting. Abstract 9002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Cobo M, Bordoni R, et al. IMpower132: PFS and safety results with 1L atezolizumab + carboplatin/cisplatin + pemetrexed in stage IV non-squamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13 Suppl 10:S332-3. 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cappuzzo F, McCleod M, Hussein M, et al. IMpower130: progression-free survival (PFS) and safety analysis from a randomised phase 3 study of carboplatin + nab-paclitaxel (CnP) with or without atezolizumab (atezo) as first-line (1L) therapy in advanced non-squamous NSCLC. Presented at: 2018 ESMO Congress. Abstract LBA53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Vynnychenko I, et al. IMpower131: primary PFS and safety analysis of a randomized phase III study of atezolizumab + carboplatin + paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel vs carboplatin + nab-paclitaxel as 1L therapy in advanced squamous NSCLC. Presented at: 2018 ASCO Annu. Meeting. Abstract LBA9000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rizvi NA, Cho BC, Reinmuth N, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab vs platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment for metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: MYSTIC. Presented at: 2018 ESMO Congress. Abstract LBA6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A, et al. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2046-54. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Govindan R, Szczesna A, Ahn MJ, et al. Phase III Trial of Ipilimumab Combined With Paclitaxel and Carboplatin in Advanced Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3449-57. 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336-41. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gelman A, Rubin D. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Statist Sci 1992;7:457-511. 10.1214/ss/1177011136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neupane B, Richer D, Bonner AJ, et al. Network meta-analysis using R: a review of currently available automated packages. PLoS One 2014;9:e115065. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks SP, Gelman A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J Comput Graph Stat 1998;7:434-55. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Valkenhoef G, Dias S, Ades AE, et al. Automated generation of node-splitting models for assessment of inconsistency in network meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 2016;7:80-93. 10.1002/jrsm.1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaimani A, Higgins JP, Mavridis D, et al. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS One 2013;8:e76654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629-34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallin JJ, Bendell JC, Funke R, et al. Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab enhances antigen-specific T-cell migration in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun 2016;7:12624. 10.1038/ncomms12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JM, Chen DS. Immune escape to PD-L1/PD-1 blockade: seven steps to success (or failure). Ann Oncol 2016;27:1492-504. 10.1093/annonc/mdw217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hegde PS, Wallin JJ, Mancao C. Predictive markers of anti-VEGF and emerging role of angiogenesis inhibitors as immunotherapeutics. Semin Cancer Biol 2018;52:117-24. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ready N, Hellmann MD, Awad MM, et al. First-Line Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (CheckMate 568): Outcomes by Programmed Death Ligand 1 and Tumor Mutational Burden as Biomarkers. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:992-1000. 10.1200/JCO.18.01042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science 2016;351:1463-9 10.1126/science.aaf1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henson SM, Macaulay R, Riddell NE, et al. Blockade of PD-1 or p38 MAP kinase signaling enhances senescent human CD8(+) T-cell proliferation by distinct pathways. Eur J Immunol 2015;45:1441-51. 10.1002/eji.201445312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lages CS, Lewkowich I, Sproles A, et al. Partial restoration of T-cell function in aged mice by in vitro blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Aging Cell 2010;9:785-98. 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00611.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Sandhu D, Seidel JA, et al. The characterization of varicella zoster virus-specific T cells in skin and blood during aging. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:1752-62. 10.1038/jid.2015.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elias R, Giobbie-Hurder A, McCleary NJ, et al. Efficacy of PD-1 & PD-L1 inhibitors in older adults: a meta-analysis. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:26. 10.1186/s40425-018-0336-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frederickson AM, Arndorfer S, Zhang I, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a network meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 2019;11:407-28. 10.2217/imt-2018-0193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang XJ, Lin JZ, Yu SH, et al. First-line checkpoint inhibitors for wild-type advanced non-small-cell cancer: a pair-wise and network meta-analysis. Immunotherapy 2019;11:311-20. 10.2217/imt-2018-0107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]