Abstract

Background:

Perceived stigma among patients with psoriasis contributes to poor quality of life.

Objective:

To determine the prevalence and predictors of stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with psoriasis among laypersons and medical trainees.

Methods:

Laypersons were recruited from Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) (n = 198). Additionally, 187 medical students were recruited via e-mail. Participants completed an online survey in which they viewed images of persons with visible psoriasis. Participants reported their desire to socially avoid the persons in the images, their emotional responses to the persons in the images, and their endorsement of psoriasis-related stereotypes and myths.

Results:

MTurk participants endorsed social avoidance items such as not wanting to shake hands with (39.4%) or have the persons in the images in their home (32.3%). Participants stereotyped persons with psoriasis as contagious (27.3%) and endorsed the myth that psoriasis is not a serious disease (26.8%). Linear regression analyses showed that having heard of or knowing someone with psoriasis predicted fewer stigmatizing attitudes (P <.05). The medical students reported less stigmatizing attitudes than the MTurk participants (P <.01).

Limitations:

Self-report, single-institution study.

Conclusion:

Stigmatizing views of persons with psoriasis are prevalent among people in the United States. Educational campaigns for the public and medical trainees may reduce stigma toward persons with psoriasis. (J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:1556–63.)

Keywords: attitudes, laypersons, medical education, psoriasis, stigma

CAPSULE SUMMARY

• Perceived stigma among patients with psoriasis contributes to poor health. Stigmatizing attitudes toward persons with psoriasis are prevalent among laypersons.

• Medical students and people who have heard of or know someone with psoriasis report less stigmatizing attitudes. Educational campaigns for the public and medical trainees may reduce stigma toward patients with psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a common autoimmune disease that leads to major impairments to health-related quality of life (QOL).1 Persons with psoriasis are at heightened risk for serious adverse mental health outcomes, including anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and suicidality,2,3 which may, in part, be due to social stigma reported by patients with visible lesions.4–8

In prior studies, patients have reported perceptions that others avoid them because of disgust and fear of contamination, and some have reported being asked to leave their jobs, gyms, and pools because of stigma.7 Patients with psoriasis who perceive and/or anticipate stigma have worse QOL, including more depression and anxiety.4–8 Effects of stigma on QOL may be independent of disease severity,5 highlighting the potency of this form of stigma. Taken together, the existing, though limited, research in this area suggests that stigma is a cardinal feature of psoriasis that requires monitoring and intervention.

Most research on this topic has assessed perceived stigma, enacted by others, from the perspective of patients with psoriasis.4–8 Relatively little research has explored laypersons’ perceptions of persons with psoriasis and their responses to seeing the visible disease markers.9 Additionally, no research to date has examined medical professionals’ attitudes toward treating patients with psoriasis. Biases against persons with other visible markers of disease (such as obesity) have been well documented among health care trainees and physicians and can adversely affect clinical care, in part by deterring stigmatized individuals from seeking treatment.10 Overall, a multifaceted understanding of laypersons’ and medical professionals’ perceptions of and responses to seeing affected skin areas in persons with psoriasis will help to advance efforts to reduce stigma, improve QOL, and increase treatment utilization.

The current research had 2 aims. First, we assessed the prevalence and predictors of stigmatizing attitudes among laypersons toward persons with psoriasis. Second, we explored stigmatizing attitudes toward patients with psoriasis among medical students and compared them with the attitudes reported by laypersons, with the hypothesis that medical students would report less stigmatizing attitudes than would laypersons because of increased knowledge of the disease.

METHODS

This study consisted of 2 quasi-experimental self-report surveys. Participants were recruited from Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) data collection service to complete a survey about skin and health. MTurk is a leading crowdsourcing tool that has been frequently used in medical and psychologic research, including in studies using images to test layperson responses to visible disease markers.11–13 For the current study, participants had to be at least 18 years old, live in the United States, and have an MTurk approval rating of 95% or higher (as determined by approval ratings from previous work completed on MTurk) to ensure data quality. Consistent with recommendations for maximizing data quality,11 participants were compensated $1.00 for completing the survey.

In addition to laypersons, medical students at a single institution were recruited via e-mail to complete a modified version of the online survey. Medical students were compensated by being entered into a raffle for a 1 in 20 chance of winning $50.

Procedures

Participants provided informed consent before proceeding to the survey. The survey displayed 8 standardized images of persons with psoriasis, with enlarged images of the psoriatic lesions. Participants completed a manipulation check item to confirm that they had attended to the images before completing all study measures. Participants ended the survey with a written debriefing statement and were compensated for their participation. This study was granted exemption by the institutional review board.

Stimuli

The images of persons with psoriasis featured patients from a university-based hospital psoriasis clinic. Patients consented to have their images used for research, and no identifying features (ie, faces) were visible. Images were pretested in a separate survey on MTurk to assess the perceived characteristics of the persons in the images. A total of 5 images were selected along with 3 additional images from publically accessible Internet sites, to represent a range of demographic characteristics and skin lesion locations (eg, leg, arm, scalp, etc). To eliminate the potential effects of skin pigmentation and/or race on responses to the skin images, only images of white adults were used.

Measures

Measures were based on scales that had previously been used to study stigmatized diseases14–20 and adapted for psoriasis. Dermatologists with expertise in psoriasis contributed to the development of all scale items.

The Desire for Social Distance Scale15 assessed participants’ desire to avoid the persons featured in the images in specific social situations. In all, 9 items were rated on a scale of 1 to 5. Item scores were averaged, with higher scores indicating stronger desire for social distance. Emotional response items18 asked participants to rate (on a scale of 1–5) the extent to which they felt compassion, pity, disgust, blame, contempt, and curiosity in response to seeing the images.

Stereotype endorsement of people with psoriasis was measured with a semantic differential scale consisting of 11 pairs of adjectives (eg, clean and dirty).17 Of 5 potential circles, participants were asked to mark the circle closest to the adjective that they believed described someone with psoriasis (coded 1–5, with 5 being closest to the negative adjective). Scores were averaged, and higher scores indicated greater endorsement of negative stereotypes. Myth endorsement19 was assessed with 15 statements representing common misconceptions about psoriasis. Participants rated their agreement with these statements (on a scale of 1–5), with higher average scores indicating greater endorsement of these myths.

All participants reported their age, race, ethnicity, and gender and whether they had ever received a diagnosis of, knew someone with, or heard of psoriasis. MTurk participants reported their highest level of education, employment status, and annual household income. Medical students reported whether they had previously learned about psoriasis and its treatment in medical school or had completed a dermatology rotation, along with their year in medical school. Medical students also completed 3 items (developed on the basis of prior research)21 about their attitudes toward treating patients with psoriasis (rated 1–5).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed with means for all continuous scales. Additionally, for ratings of social distance, stereotypes, and myths, the percentage of participants scoring a 4 or 5 on each item (indicating stronger item endorsement) was computed to create dichotomous, item-specific “prevalence” variables. For MTurk participants, a linear regression model was used to test the effects on all continuous outcomes (social distance, emotional responses, stereotypes, and myths) of participant age, sex, race, ethnicity, employment, education, and income and whether participants had heard of, known someone with, or received a diagnosis of psoriasis. For medical students, linear regression models were used to test the effects on all outcomes of participant age, gender, race, ethnicity, year in medical school, and completion of a dermatology rotation, as well as reports of knowing someone with, having heard of, having received a diagnosis of, learning about treatment for, and observing treatment of psoriasis. Differences in sample characteristics between the MTurk and medical student participants were identified by using analysis of variance and logistic regression. Between-sample differences on all outcomes were examined by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), controlling for characteristics that differed between samples. To adjust for multiple comparisons, a significance level of P less than .01 was used for the ANCOVA results. Analyses are reported in adherence with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

RESULTS

In total, 201 layperson participants completed the psoriasis survey. Of those 201 participants, 3 did not pass the data quality assessment,* leaving 198 participants. A total of 216 medical students consented to complete the survey, of whom 195 completed at least the first scale; 8 participants were excluded because of incomplete surveys, leaving 187 participants (Tables I and II).

Table I.

Participant characteristics

| Variable | MTurk participants (n = 198) |

Medical students (n = 187) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean ± SD | 33.4 ± 9.9 | 25.3 ± 2.5 |

| Gender, n, (%) | ||

| Men | 115 (58.1%) | 78 (41.7%) |

| Women | 82 (41.4%) | 109 (58.3%) |

| Nonbinary/other | 1 (0.5%) | 0 |

| Race/ethnicity, n, (%) | ||

| White | 162 (81.8%) | 115 (61.5%) |

| Black/African American | 12 (6.1%) | 8 (4.3%) |

| Asian | 20 (10.1%) | 49 (26.2%) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 6 (3.0%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Caribbean Islander | 0 | 2 (1.1%) |

| Multiracial | 2 (1.0%) | 7 (3.7%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 18 (9.1%) | 23 (12.3%) |

| Employed, n, (%) | 159 (80.3%) | — |

| College-educated, n, (%) | 125 (63.1%) | — |

| Income of ≥$50,000, n, (%) | 98 (49.5%) | — |

| Year in medical school, mean ± SD | — | 2.6 ± 1.4 |

| Has a diagnosed skin disease, n, (%) | 6 (3.0%) | 3 (1.6%) |

| Know someone with skin disease, n, (%) | 52 (26.3%) | 96 (51.3%) |

| Heard of skin disease, n, (%) | 152 (76.8%) | 179 (95.7%) |

| Learned about treatment, n, (%) | — | 137 (73.7%) |

| Treated or observed treatment, n, (%) | — | 54 (28.9%) |

| Completed dermatology rotation, n, (%) | — | 14 (7.5%) |

MTurk, Mechanical Turk; SD, standard deviation.

Table II.

Average scores for stigmatizing attitudes

| Variable | MTurk participants, mean ± SD |

Medical students, mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Social distance | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 0.7* |

| Emotions | ||

| Compassion | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 0.8* |

| Pity | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 3.1 ± 1.1 |

| Disgust | 2.4 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 0.9* |

| Blame | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.4* |

| Contempt | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 0.5* |

| Curiosity | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.0* |

| Stereotypes | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

| Myths | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.4* |

| Attitudes toward treating patients | — | 3.7 ± 0.7 |

MTurk, Mechanical Turk; SD, standard deviation.

Indicates statistically significant difference (P <.01), with analyses of covariance controlling for covariates that differed between groups (age, gender, race, knowing someone with psoriasis, and having heard of psoriasis).

Layperson attitudes

Prevalence of stigmatizing attitudes.

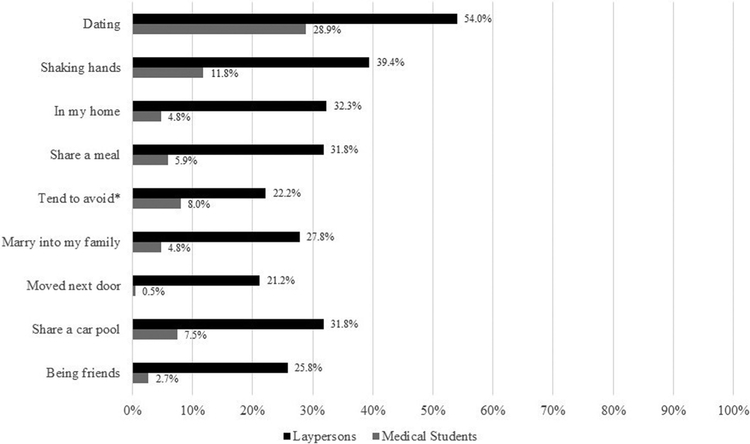

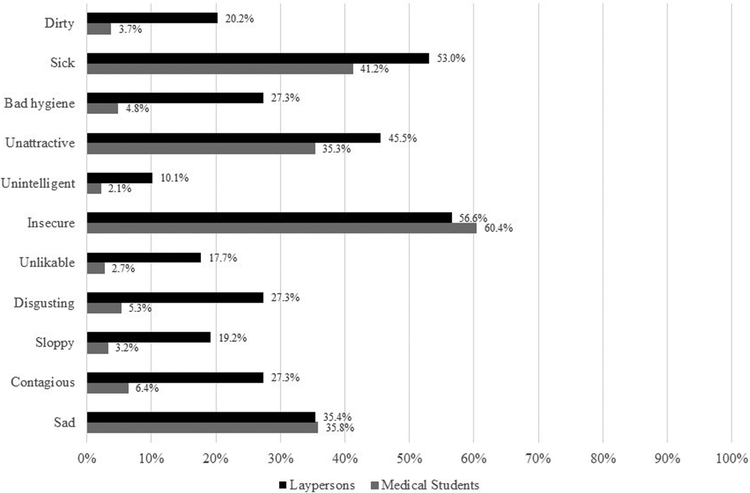

On average, participants endorsed 2.9 plus or minus 3.1 out of a potential 9 social distance items. The items endorsed with the highest frequency were not wanting to date (54.0% [95% confidence interval (CI), 46.8%–61.1%]), shake hands with (39.4% [95% CI, 32.5%–46.6%]), or have in one’s home (32.3% [95% CI, 25.9%–39.3%]) the persons with psoriasis who were featured in the images (Fig 1). Participants endorsed an average of 3.4 plus or minus 3.1 negative stereotypes. The most frequently endorsed stereotypes were that people with psoriasis are insecure (56.6% [95% CI, 49.4%–63.6%]), sick (53.0 [95% CI, 45.8%–60.1%]), and unattractive (45.5% [95% CI, 38.3%–52.7%]) (Fig 2). Participants endorsed 2.5 plus or minus 2.4 myths. The most frequently endorsed myths were that psoriasis affects only the skin (34.3% [95% CI, 27.8%–41.4%]) and that psoriasis is not a serious disease (26.8% [95% CI, 20.7%–33.5%]) (Fig 3).

Fig 1.

Percentage of laypersons and medical students endorsing Desire for Social Distance Scale items. Item endorsement indicates that participants reported that they would be uncomfortable in the specific social situations and/or contexts with the persons with psoriasis featured in the images (*item for tend to avoid is scored such that endorsement indicates that participants tend to avoid the persons featured in the images).

*(the 3 participants selected the same rating for all items in all scales).

Fig 2.

Percentage of laypersons and medical students endorsing negative stereotypes of persons with psoriasis.

Fig 3.

Percentage of laypersons and medical students endorsing myths about persons with psoriasis. *Items were reverse-scored, such that endorsement indicates that participants did NOT endorse these statements (ie, percentages are displayed for participants who believed that psoriasis is NOT physically painful or a serious disease).

Predictors of stigmatizing attitudes.

Regression results showed that, compared with participants who had not heard of or known someone with psoriasis, those who had reported reduced desire for social distance (heard of someone with psoriasis, β = −0.20, P = .005; know someone with psoriasis, β = −0.29, P<.001). These 2 variables also predicted less endorsement of negative stereotypes (heard of someone with psoriasis, β = −0.22, P = .002; know someone with psoriasis, β = −0.19, P = .011) and myths (heard of someone with psoriasis, β = −0.45, P<.001; know someone with psoriasis, β = −0.16, P = .023). Additionally, having heard of psoriasis predicted greater compassion (β = 0.20, P < .007) (as did female gender [β = 0.18, P = .012] and older age [β = 0.16, P = .034]), as well as less blame (β = −0.31, P<.001) and less contempt (β = −0.36, P <.001). Women (compared with men) reported less disgust (β = −0.14, P = .043). Of note, having received a diagnosis of psoriasis predicted stronger myth endorsement (β = 0.14, P = .028), although only 6 participants reported having received this diagnosis.

Medical student attitudes

Prevalence of stigmatizing attitudes.

Medical students endorsed an average of 0.7 plus or minus 1.2 social distance items, 2.0 plus or minus 1.7 stereotypes, and 0.8 plus or minus 1.1 myths. The social distance items rated with the highest frequency were not wanting to date (28.9% [95% CI, 22.5%–36.0%]) or shake hands with the persons in the images (11.8% [95% CI, 7.5%–17.3%]) (Fig 1). More than 60% of participants (95% CI, 53.0%–67.5%) reported believing that persons with psoriasis are insecure, 41.2% (95% CI, 34.0%−48.6%) rated them as sick, and 35.8% (95% CI, 29.0%–43.2%) rated them as sad (Fig 2). The most frequently endorsed myths were that psoriasis is not physically painful (18.2% [95% CI, 12.9%–24.5%]), is not a serious disease (12.8% [95% CI, 8.4%–18.5%]), does not negatively affect physical health (11.8% [95% CI, 7.5%–17.3%]), and can be cured (10.7% [95% CI, 6.7%–16.0%]) (Fig 3).

Predictors of stigmatizing attitudes.

Regression results showed less desire for social distance among women (β = −0.16, P = .022) and Hispanics (β = −0.16, P = .029) and more compassion (women β = 0.22, P = .003; Hispanic β = 0.17, P = .022) than among men and non-Hispanics. Endorsement of myths was weaker among participants who had learned about treatment for psoriasis (β = −0.31, P <.001), knew someone with psoriasis (β = −0.16, P = .01), or had heard of psoriasis (β = −0.32, P<.001). Students who had completed a dermatology rotation reported less compassion than did those who had not (β = −0.17, P = .031). Significant predictors of more positive attitudes toward treating patients with psoriasis were older age (β = 0.17, P = .047), female gender (β = 0.14, P = .045), having learned about treatment for psoriasis (β = 0.27, P = .002), and having completed a dermatology rotation (β = 0.22, P = .002).

Comparison between the attitudes of laypersons and medical students

Compared with the MTurk sample, medical students were less likely to be white (odds ratio [OR], 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–0.6; P <.001) and more likely to be women (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3–3.0; P = .001). The medical students were also younger than the participants (P <.001) and more likely to know someone with psoriasis (OR, 3.0; 95% CI, 1.9–4.5; P<.001) and have heard of psoriasis (OR, 6.8; 95% CI, 3.1–14.8; P <.001).

Controlling for age, gender, race, having heard of, and knowing someone with psoriasis, ANCOVA results showed, in comparison to MTurk participants, medical students reported less desire for social distance from the persons with psoriasis featured in the images and weaker endorsement of myths (P<.001). Medical students also expressed greater compassion (P = .008) and curiosity (P <.001) and less disgust, blame, and contempt (P <.001) in response to the images of persons with psoriasis than did the MTurk participants.

DISCUSSION

We conducted an evaluation of stigma toward persons with psoriasis among laypersons and medical trainees. The results showed that a substantial percentage of laypersons reported a desire to avoid persons with visible psoriatic lesions in routine social and work-related situations. Participants also endorsed negative stereotypes and myths, such as beliefs that persons with psoriasis are sad, insecure, and contagious.

Medical students reported less stigmatizing attitudes toward individuals with psoriasis than did the MTurk participants. The few students who completed a dermatology rotation reported less compassion than those who did not. Although we caution against drawing conclusions from our limited data, this finding could reflect the fact that these students may have learned about severe skin diseases that lack any effective treatments (compared with psoriasis, in which the students observe remarkable improvements from existing therapies), thus reducing their compassion toward patients with psoriasis. The effect could also be attributed to a broader phenomenon of “clinical detachment” that has been observed among students during medical training.22 Nevertheless, learning about treatment for psoriasis and completing a dermatology rotation was associated with more positive attitudes toward treating patients with psoriasis.

Strengths of the current study include assessment of psoriasis-related stigma across groups that have not previously been evaluated (given that most studies on psoriasis-related stigma to date have exclusively assessed perceived stigma among patients) and the use of validated instruments to measure stigma. Moreover, the MTurk sample provides an estimate of the prevalence of stigmatizing views toward patients with psoriasis in a broad cross-section of Americans. The study’s novel exploration of psoriasis stigma among medical trainees represents a step toward enhancing sensitivity among health care professionals who may encounter patients with stigmatizing skin conditions such as psoriasis.

Limitations of the current study include potential social desirability bias in reporting stigmatizing attitudes, reliance solely on self-report attitudinal measures, and assessment of medical trainees from a single institution. The images used in this study featured white adults only; future research should incorporate images of persons of color to determine the effects of psoriasis-related stigma across race/ethnicity. Additionally, 27.3% of participants rated persons with psoriasis as contagious on the semantic differential scale assessing stereotype endorsement, whereas only 13.1% agreed that psoriasis is contagious in the myths questionnaire. Further attention should be paid to item wording and scale ratings in future studies to ensure accuracy in assessing stigmatizing beliefs. We used conservative scoring to dichotomize items as yes or no for endorsement by only including participants who scored 4 or higher. Participants who were neutral (ie, marked the scale midpoint of 3) did not express disagreement with stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs, signifying that they may still hold misconceptions about psoriasis and those affected by it.

This study’s findings have implications for public health campaigns and patient care. Educational campaigns and advertisements that show visible lesions, while providing accurate information to counteract stereotypes and myths, could potentially diminish laypersons’ negative responses to seeing psoriatic lesions. Future studies could develop and test the effects of such campaigns on attitudes and avoidant behavior toward persons with psoriasis. Similarly, efforts to incorporate standardized patients with psoriasis into general medical education could help to increase knowledge and sensitivity toward these patients. Additional studies are also needed to understand the potential role of implicit bias in shaping laypersons’ and medical professionals’ responses to persons with psoriasis, as well as potential effects of race or skin color on stigmatizing attitudes. Understanding the bias against persons with psoriasis from the general public and health care professionals, as well as patients’ own anticipated and perceived stigma, is necessary to develop interventions that reduce the stigma perceived by patients with psoriasis and its adverse psychologic and QOL consequences.

Funding sources:

Supported by a grant from the Edwin and Fannie Gray Hall Center for Human Appearance at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr Pearl is supported in part by a mentored patient-oriented research career development award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health (grant K23HL140176). Dr Takeshita is supported in part by a mentored patient-oriented research career development award from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases/National Institutes of Health (grant 5K23AR068433).

Disclosure: Dr Gelfand served as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, Regeneron, UCB (Data Safety and Monitoring Board), and Sanofi and Pfizer Inc, receiving honoraria; in addition, he receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Abbvie, Janssen, Novartis Corp, Sanofi, Celgene, Ortho Dermatologics, and Pfizer Inc, and he has received payment for CME work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Eli Lilly and Company and Ortho Dermatologics. In addition, Dr Gelfand is a copatent holder of resiquimod for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and he is a deputy editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology, receiving honoraria from the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Dr Takeshita receives a research grant from Pfizer Inc (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) and has received payment for CME work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Eli Lilly and Company and Novartis. Dr Pearl and Dr Wan have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abbreviations used:

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- CI

confidence interval

- MTurk

Mechanical Turk

- OR

odds ratio

- QOL

quality of life

Footnotes

A preliminary analysis of the current data was presented at the 2018 Meeting International Investigative Dermatology, Orlando, FL, May 16–19, 2018.

REFERENCES

- 1.deKorte J, Mombers F, Bos J, Sprangers M. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9(2):140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira B, Abreu J, Reis J, Figueiredo A. Psoriasis and associated psychiatric disorders: a systematic review on etiopathogenesis and clinical correlation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9(6):36–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Cristoph P, Gelfand JM. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(8): 891–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardy D, Besser A, Amir M, Gesthalter B, Biton A, Buskilas D. Experiences of stigmatization play a role in mediating the impact of disease severity on quality of life in psoriasis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:736–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richards H, Fortune D, Griffiths C, Main C. The contribution of perceptions of stigmatisation to disability in patients with psoriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2001;50:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid-Ott G, Schallmayer S, Calliess I. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis and psoriasis arthritis with a special focus on stigmatization experiences. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:547–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginsburg I, Link B. Psychosocial consequences of rejection and stigma feelings in psoriasis patients. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32: 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawro M, Maurer M, Weller K, et al. Lesions on the back of hands and female gender predispose to stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;76(4): 648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Wang K, et al. The burden of stigma on health and well-being: a taxonomy of concealment, course, disruptiveness, aesthetics, origin, and peril across 93 stigmas. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2018;44(4):451–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, Ryn Mv. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev 2015;16: 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspect Psychol Sci 2011;6(1):3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzaferro DM, Wes AM, Naran S, Pearl R, Bartlett S, Taylor JA. Orthognathic surgery has a significant effect on perceived personality traits and emotional expressions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(5):971–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tse RW, Oh E, Gruss JS, Hopper RA, Birgfield CB. Crowdsourcing as a novel method to evaluate aesthetic outcomes of treatmetn for unilateral cleft lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016; 138(4):864–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89: 1328–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearl RL, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Positive media portrayals of obese persons: impact on attitudes and image preferences. Health Psychol. 2012;31(6):821–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacon JG, Scheltema KE, Robinson BE. Fat phobia scale revisited: the short form. Int J Obes. 2001;25:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruttan RL, McDonnell M, Nordgren LF. Having “been there” doesn’t mean I care: when prior experience reduces compassion for emotional distress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(4): 610–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allison DB, Basile VC, Yuker HE. The measurement of attitudes toward and beliefs about obese persons. Int J Eat Disord. 1991; 10:599–607. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latner J, Stunkard A. Getting worse: the stigmatization of obese children. Obesity. 2003;11(3):452–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Puhl RM, Luedicke J, Grilo CM. Obesity bias in training: attitudes, beliefs, and observations among advanced trainees in professional health disciplines. Obesity. 2014;22(4):1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulehan J, Williams PC. Vanquishing virtue: the impact of medical education. Acad Med. 2001;76:598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]