Abstract

High levels of family accommodation (FA), or parental involvement in child symptoms, are associated with child anxiety symptom severity. The strength of associations has varied across studies, however, highlighting the need to identify moderating variables. We investigated whether anxiety sensitivity (AS) moderated the FA-anxiety symptom severity association in clinically anxious children (N = 103, ages 6–17; mean age 11.07 years). We collected child and mother ratings of FA, child anxiety symptom severity, and child AS ratings. AS significantly moderated the FA-child anxiety severity link. Specifically, this link was significant for low-AS but not high-AS children. Findings suggest that FA may operate in the typically observed fashion for low-AS children—alleviating immediate distress while inadvertently exacerbating longer-term anxiety—whereas high-AS children may experience distress following anxiety-provoking stimuli regardless of FA. Assessing AS in research and clinical settings may help identify subsets of children for whom FA is more closely tied to anxiety severity.

Keywords: Anxiety sensitivity, Family accommodation, Child anxiety

Introduction

Family accommodation (FA) of childhood anxiety disorders refers to changes to families’ behaviors and routines that aim to reduce child distress, to minimize exposure to fear- and anxiety-provoking stimuli, and to alleviate worry [1–4]. FA most often involves two domains of parent behaviors: (1) modification of family routines (e.g., staying home from work; cancelling family outings) and (2) participation in their child’s symptom-driven behaviors (e.g., ordering for the child in a restaurant; providing repeated reassurance) [3, 5].

FA allays child distress in the short-term but can maintain child anxiety and avoidance in the long-term [5–7]. In samples of clinically anxious children, data show that high levels of child- and parent-rated FA are associated with high child- and parent-rated anxiety symptom severity in the child [2, 4, 8]. In one study, reductions in FA over the course of treatment were also associated with positive child anxiety treatment response, suggesting FA’s relevance to clinical outcomes [9]. Instrumental learning processes may explain in part the FA-child anxiety severity association. Because FA entails parental responsiveness and attention to their child’s expressed anxious and avoidant behaviors, parents who engage in high FA are inadvertently providing positive reinforcement to their child’s anxiety. FA also entails parental efforts to reduce or eliminate the source of their child’s anxiety, thereby inadvertently providing negative reinforcement to their child’s anxiety.

Despite consistent, positive associations between levels of FA and child anxiety symptom severity, the zero-order correlations have ranged considerably across studies from about 0.10 to 0.50 [4, 8]. Many factors likely contribute to the observed correlation ranges, including the likelihood that particular child characteristics moderate the association. Settipani and Kendall is the only study to assess moderators of the FA-child anxiety association, but they examined maternal factors that may moderate the strength of the FA-child anxiety severity link [10]. Specifically, in a sample of mothers of 70 clinically anxious children and adolescents (7–17 years) that relied on mothers’ ratings for all variables, maternal empathy emerged as a significant moderator of the FA-child anxiety link. Mothers who rated themselves high (versus low) in maternal empathy tended to rate themselves high in FA in response to anxiety in their child. Maternal anxiety also emerged as a significant moderator, although the direction of the moderated effects varied by primary child anxiety diagnosis.

Child factors are also likely important in understanding the FA-child anxiety link, but no research to date has tested child factors as moderators of this association. Both heritable and learned child vulnerability factors are potential moderators [11]. Understanding child vulnerability factors can aid the identification of children who are most likely to experience high anxiety symptom severity when their parents are highly accommodating. These vulnerabilities may influence ways in which parents respond to their children’s anxiety and the extent to which they engage in accommodation behaviors, leading to differential associations between FA and child symptom severity. In this study, we focus on one particular child vulnerability factor, anxiety sensitivity (AS), as a potential moderator of the FA-child anxiety link.

Anxiety Sensitivity

Anxiety sensitivity is a fear of anxiety-related sensations (e.g., increased heart rate), due to beliefs that these sensations have harmful physical, psychological, or social consequences [12]. Children and adults with high AS perceive somatic sensations as danger signals that can intensify their anxiety severity [13, 14]. AS also contributes to avoidance of feared stimuli in clinically anxious children. Lebowitz et al. found the association between fear of spiders and behavioral avoidance of spider stimuli was significant for high-AS children, but not for children with either low or average levels of AS [15]. Thus, by rendering internal anxiety-related sensations more aversive, high AS heightened children’s motivation to avoid feared situations.

Children’s levels of AS have shown consistent links to environmental factors, including parenting behaviors. Research with college student samples suggests that parental rejection and hostility [16], emotional maltreatment [17], and over-attentiveness to child anxiety [18], are closely tied to high AS in offspring. As one relevant example, Watt et al. found high-AS college students retrospectively reported greater parental reinforcement of sick-role behavior during childhood, particularly in response to somatic symptoms, compared with low-AS college students. Another study found adolescent AS moderated the relation between anxiety in parents and adolescents, with this link emerging as stronger in high-AS adolescents than low-AS adolescents [19].

The Role of AS in the FA-Anxiety Severity Link

Given previously observed associations between parent factors (e.g., parental anxiety; reinforcement of anxiety-related “sick behaviors”) and child anxiety in the presence of AS, FA may be an important contributor to child anxiety among children with high levels of AS. Parents who engage in FA may be communicating to their anxious child that the child’s anxiety-related sensations signify genuine danger [20]. For the high-AS child, FA may trigger and/or affirm the child’s tendencies to fear and avoid his or her anxiety-related somatic or physiological sensations. If this is the case, a plausible prediction is that FA would relate most strongly to higher anxiety severity in high-AS children compared with low-AS children.

FA may be also be plausibly associated with high anxiety in low-AS children more strongly than in high-AS children. Several considerations support this hypothesis. One, the focus on internal somatic sensations in high-AS children may lessen the impact of parental behaviors, including FA. A high-AS child who experiences a panic attack at school may, for example, focus excessively on his or her internal sensations even if allowed to stay home, whereas a low-AS child who is less focused on internal sensations may be more likely to experience immediate relief when accommodated by parents. Low-AS children may therefore be more susceptible to behavioral shaping via FA, particularly though positive reinforcement processes. For instance, low-AS children may find parental attention more rewarding and distress-alleviating than high-AS children. Thus, low-AS children may be highly motivated to seek accommodation in the future. Parents of low-AS children, in turn, may find FA to be a highly effective means of alleviating the child’s anxiety—at least in the short-term. FA may therefore become a powerful means of negative reinforcement for parents of low-AS children. Two, because AS tends to predate anxiety disorder onset [21], parents of high-AS children may be accustomed to their child’s behavioral avoidance or signs of distress when the anxiety disorder onsets. These parents may experience less distress in response to their child’s anxiety symptoms, and thus less motivation to engage in FA compared with parents with low-AS children for whom anxiety and avoidance might be newer developments. Three, as a function of their cognitive vulnerability, high-AS children may be highly motivated to avoid potentially anxiety-provoking stimuli even when parents are more accommodating, leaving little room for further variability in anxiety symptoms due to family interaction patterns.

Child Sex and Age

Sex and age are consistently associated with levels of anxiety and AS in children. Compared to males, females have reported higher levels of anxiety symptoms [22, 23] and AS [24]. Age-related differences in child anxiety symptoms are also well-documented, though patterns of age differences differ by anxiety symptom type [25, 26]. Evidence is mixed regarding differences in AS by child age [27, 28], but AS tends to correlate more strongly with anxiety symptom severity in adults and adolescents than in younger children [24].

Child sex and age may also relate to parents’ levels of FA, though these links have not been thoroughly tested. One study found higher FA among parents of girls than boys [2], but another reported no differences in FA by child sex [8]. In a study of clinically anxious school-aged children, child age was not associated with FA [2], but studies with broader age ranges are needed to parse this possibility.

It is plausible that parents of girls engage in in more FA than parents of boys, because for example parents of high-anxiety girls have displayed more over-involved, autonomy- restricting parenting styles than parents of high-anxiety boys [29]. Parents of younger children might also engage in more FA than parents of adolescents, as involvement in children’s routines and behaviors may seem more normative for younger children. There is therefore sound reason to consider child sex and age sex in links between anxiety severity, AS, and FA in clinically anxious children.

Study Aims

The aim of this study was to examine AS as a moderator of the association between FA and severity of symptoms in children with anxiety disorders. We considered two alternative hypotheses, in light of the above review. The first is that the FA-child anxiety association would be stronger for high-AS children than low-AS children; the second is that the association would be stronger for low-AS children than high-AS children. Regarding specific child anxiety dimensions, we predicted that the moderating effect of AS would be strongest for somatic anxiety (given robust connections between AS and panic across child and adult populations). We focused on two domains of FA-related behaviors, which have been identified via factor analyses as empirically and conceptually distinct from one another [2, 30]: maternal participation in child symptoms and modification of family routines. We addressed biases inherent to single-informant studies by testing study hypotheses using both mother and child ratings of FA. Given the data supporting roles of child age and gender in anxiety severity, AS, and FA, we included both of these factors in all study analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 103 children and adolescents ages 6–17 (mean age = 11.07 years, SD = 3.12) and their mothers, presenting to a child anxiety specialty research clinic in the Northeastern United States. Participating children met criteria for DSM-5 primary anxiety disorders based on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule—Child/Parent Version [31]. The most common primary anxiety disorder diagnosis was generalized anxiety disorder (34%), followed by social phobia (30%), separation anxiety disorder (19%), specific phobias (11%), panic disorder (4%) and agoraphobia (2%). Comorbidity between the anxiety disorders was high (79% of children had more than one anxiety diagnosis), as has been typical of other youth anxiety samples [32], as was comorbidity with depression (32%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (18%), and obsessive compulsive disorder (13%). Most children were Caucasian (85.4%) and non-Hispanic (94.2%); others were multiracial (10.7%), African American (1.9%), and Asian-American (1.9%). Families’ annual incomes ranged from below $21,000 to above $150,000, with 78.8% of families reporting incomes of over $81,000 per year.

Mothers and children provided written informed consent and assent, respectively, prior to study procedures, which were approved by the University Institutional Review Board. Child questionnaires were administered in the presence of a trained research assistant, who was available to answer questions and clarify questionnaire items as needed.

Measures

Child-Completed Measures

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, 2nd Edition (MASC2) [33]

The 50-item MASC2 assesses anxiety symptoms in children. The MASC2 is a recently revised edition of the MASC, which has shown strong psychometric properties in nationally representative child samples [34]. Each MASC2 item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 3 (often). Sums of these items yield a total l anxiety score based on all 50 items and subscales for specific anxiety domains (separation anxiety, social anxiety, physical symptoms; harm avoidance, generalized anxiety; obsessive–compulsive symptoms). In this study, we used the MASC2 total score and each subscale score except for the OCD subscale, which is no longer classified as an anxiety disorders in DSM-5. Internal consistency for the MASC2 total score was α = 0.94; for subscales, alphas ranged from 0.72 (harm avoidance) to 0.89 (physical symptoms).

Family Accommodation Scale Anxiety—Child Report (FASA-CR) [2, 8]

Children rated their mothers’ FA on the FASA-CR. FASA-CR includes nine accommodation items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, yielding two subscales: (1) Participation (5 items) that assesses parent engagement in child symptom-related behaviors (e.g., assisting avoidance); and (2) Modification (4 items) that assesses parent changes in routines or activities due to the child’s anxiety symptoms [2, 8]. Research supports a two-factor structure for the FASA-CR and FASA (the parent-report analogue), with “Participation” and “Modification” emerging as distinct types of FA [2, 30]. We therefore examined these sub-scales separately. Both subscales have satisfactory internal consistency, and convergent and divergent validity [8]. In the present study, internal consistencies for the FASA-CR Participation and Modification subscales were α = 0.77 and α = 0.79, respectively.

Childhood Anxiety Sensitivity Index (CASI) [14]

Children completed the CASI, an 18-item child-report questionnaire designed to assess the extent to which children believe their anxiety symptoms will have negative consequences. Responses are scored on a scale from 1 (none) to 3 (a lot) and summed to yield a total AS score. The CASI has exhibited incremental validity in predicting fear beyond that accounted for by trait anxiety in children and adolescents [28]; relative stability across a 2-week period in a clinic-referred child sample (r = 0.76) [14]; and internal consistency above 0.80 [14, 35]. The internal consistency estimate in the current sample was α = 0.90.

Mother-Completed Measures

Family Accommodation Scale Anxiety (FASA) [2]

Mothers completed the FASA, which includes 9 items that parallel those on FASA-CR and contain the same subscales of Participation and Modification. Past research shows good internal consistency and convergent validity of the sub-scales [2, 8]. In the present sample, internal consistencies for the FASA Participation and Modification subscales were α = 0.81 and α = 0.84, respectively.

Data Analyses

We first evaluated associations between child anxiety severity (including MASC total score and all subscales), FA-Participation, FA-Modification, and AS by child age and sex using zero-order and point-serial correlations. Due to previous and hypothesized associations between primary study variables and both child sex and age, both variables were included in Step 1 of each hierarchical linear regression (described below) as theoretically-driven covariates.

We then conducted hierarchical linear regressions, with child anxiety MASC2 ratings as the dependent variable, to test hypothesized moderation effects (variables were centered prior to analyses to decrease collinearity). In Step 1 of these regressions, FA and AS were entered as independent variables, along with child sex and age. In Step 2, we included the interaction term between the two independent variables: either AS × FA-Participation or AS × FA-Modification. Significant change in R2 from Step 1 to Step 2 is indicative of moderation [36].

We tested whether AS moderated the link between child anxiety severity and the Participation and Modification subscales of the FASA/FASA-CR, conducting parallel models for child and mother reports of FA. We first examined moderation of the link between FA and total child anxiety ratings. If the interaction effect was significant, we repeated the procedure examining moderation of each MASC2 subscale. For all significant moderation effects, we used the PROCESS macro for SPSS [37] to calculate simple slopes for the association between FA and child anxiety severity for low (−1 SD below the mean), average (mean), and high (+1 SD above the mean) levels of the moderator, using bootstrapping procedures with 2000 samples.

We did not invoke experimentwise controls (i.e., corrections for multiple tests) in consideration of several factors, including sample size and statistical power, risk of Type II error, and the study’s research questions [38]. Due to the moderate sample size, as well as the novelty of the relations under investigation, we determined that invoking experimentwise controls would be costly to statistical power, creating significant risk of missing a true effect. Alpha was therefore set at 0.05.

Results

Descriptives and Correlations

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for all study variables, as well as child age and sex (point-serial correlations), are presented in Table 1. Correlations among primary study variables were largely in anticipated directions, with two exceptions. First, neither mother-rated FA subscale correlated significantly with child AS. Second, the mother-rated FA-Modification subscale did not correlate significantly with any child-rated MASC2 anxiety subscale. To determine whether the lack of a significant correlation with the child’s ratings was due to child sex and/or child age, we conducted partial correlations between mother-rated FA-modification and child MASC2 total and subscale scores, controlling for these two child variables. Correlations between FA-Modification and child anxiety symptoms remained non-significant.

Table 1.

Descriptives and zero-order correlations, all study variables

| Mean | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FA child-report: Modification | 3.72 | 3.40 | .56** | .39** | .30** | .29** | .28** | .19* | .26** | .20** | .27** | .14 | −.04 | .02 |

| 2. FA child-report: Participation | 9.17 | 4.71 | – | .43** | .45** | .34** | .38** | .46** | .29** | .29** | .22* | .36** | −.26** | .20* |

| 3. FA mother-report: Modification | 5.72 | 4.26 | – | .70** | .09 | .07 | .13 | .16 | .05 | .11 | .13 | −.12 | −.09 | |

| 4. FA mother-report: Participation | 1.73 | 4.71 | – | .05 | .19* | .30** | .22* | −.03 | .07 | .04 | −.27** | .09 | ||

| 5. Child Anxiety Sensitivity | 32.63 | 7.92 | – | .66** | .32** | .62** | .50** | .62** | .32** | .10 | .22* | |||

| 6. Child total anxiety symptoms | 72.74 | 24.13 | – | .64** | .89** | .78** | .81** | .58** | .02 | .30** | ||||

| 7. Child separation anxiety symptoms | 12.13 | 5.62 | – | .46** | .33** | .39** | .42** | −.25** | .23** | |||||

| 8. Child generalized anxiety symptoms | 15.04 | 5.46 | – | .66** | .81** | 49** | .06 | .28** | ||||||

| 9. Child social anxiety symptoms | 14.49 | 6.92 | – | .53** | .34** | .15 | .25** | |||||||

| 1. Child physical symptoms | 14.67 | 7.81 | – | .30** | .15 | .18* | ||||||||

| 11. Child harm avoidance | 16.51 | 3.72 | – | −.10 | .28** | |||||||||

| 12. Child age | 11.07 | 3.12 | – | −.01 | ||||||||||

| 13. Child sex | N/A | N/A | – |

p < .05,

p < .01

As presented in Table 1, girls reported significantly higher overall anxiety symptom severity than boys, as well as higher separation anxiety symptoms, generalized anxiety symptoms, social anxiety symptoms, and harm avoidance. Girls also reported significantly higher AS than boys. Neither child- nor mother-rated FA was significantly associated with child sex. However, both child- and mother-rated FA-Participation were significantly associated with younger child age. Total child anxiety symptom severity, AS, and FA-Modification were not significantly associated with child age.

Moderation by AS: Child-Report FA (See Table 2 for AS × FA Moderation Test Results, with Total MASC2 Specified as the DV, Across Parent- and Child-Rated FA)

Table 2.

Full regression results, FA × AS interactions across child- and mother-reported FA

| Child-report FA: Participation | Child-report FA: Modification | Mother-report FA: Participation | Mother-report FA: Modification | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor (Step 2 variable) | DV Total child anxiety severity | Predictor (Step 2 variable) | DV Total child anxiety severity | Predictor (Step 2 variable) | DV Total child anxiety severity | Predictor (Step 2 variable) | DV Total child anxiety severity | ||||

| β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | β | ΔR2 | ||||

| Step 1 | .50** | Step 1 | .50** | Step 1 | .47** | Step 1 | .48** | ||||

| Child age | .01 | Child age | −.02 | Child age | .20 | Child age | −.04 | ||||

| Female gender | .10 | Female gender | .17* | Female gender | .12 | Female gender | .15* | ||||

| Child AS | 1.00** | Child AS | .82** | Child AS | 1.03** | Child AS | .68** | ||||

| Child-report FA: Participation | .93** | Child-report FA: Modification | 1.00** | Mother-report FA: Participation | .71* | Mother-report FA: Modification | .39 | ||||

| Step 2 | .05** | Step 2 | .05** | Step 2 | .02* | Step 2 | .00 | ||||

| FA-Participation (child) × AS | −99** | FA-Modification (child) × AS | −1.03** | FA-Participation (mother) × AS | −.73* | FA-Modification (mother) × AS | −.09 | ||||

Regression coefficients are standardized

p < .05,

p < .01

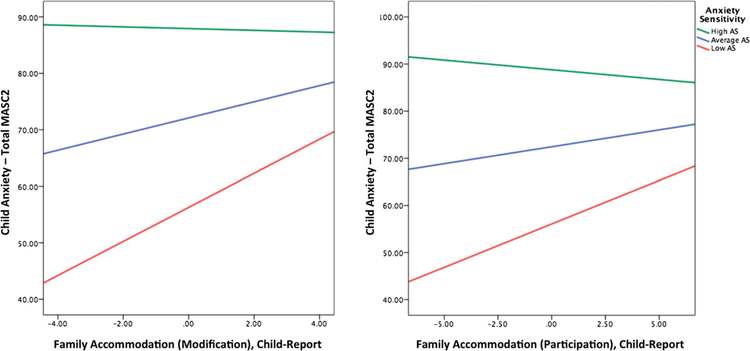

Based on child-rated FA, the FA-Participation × AS interaction produced a significant change in R2 for total child anxiety symptoms, ΔF(1, 98) = 13.42, ΔR2 = 0.05, p < .001, as did the FA-Modification × AS interaction, ΔF(1, 98) = 12.46, ΔR2 = 0.05, p = .001. Figure 1 illustrates the simple effects (regression lines) for both of these patterns. We next examined the slope of associations between both subscales of child-rated FA and child anxiety at different levels of child AS. For FA-Modification, the FA-child anxiety link was strongest among low-AS children [β = 3.01, t = 3.60, p < .001, 95% CI (1.36, 4.67)], weaker but still significant for average-AS children [β = 1.43, t = 2.59, p = .02, 95% CI (0.33, 2.52)], and non-significant for high-AS children [β = −0.15, t = −0.27, p = .78, 95% CI (−1.26, 0.94)]. A similar pattern emerged for FA-Participation, with the FA-child anxiety link emerging as strongest for low-AS children [β = 1.84, t = 3.71, p < .001, 95% CI (0.86, 2.83)] and as non-significant for average-AS [β = 0.72, t = 1.92, p = .06, 95% CI (−0.02, 1.46)] and high-AS children [β = −0.41, t = −0.87, p = .38, 95% CI (−1.34, 0.52)].

Fig. 1.

Child anxiety sensitivity moderates relations between child-reported family accommodation (modification, left; participation, right) and overall child anxiety symptom severity

Because AS moderated relations between both child-rated FA-Modification and FA-Participation and child overall anxiety symptom severity, we conducted additional hierarchical regressions to test whether these effects were specific to anxiety dimensions based on MASC2 sub-scales. The FA-Participation × AS interaction produced a significant change in R2 for severity of child separation anxiety, ΔF(1, 98) = 7.26, ΔR2 = 0.04, p = .008, and social anxiety, ΔF(1, 98) = 5.20, ΔR2 = 0.03, p = .02, but not for harm avoidance, physical symptoms, or generalized anxiety. Additionally, the FA-Modification × AS interaction produced a significant change in R2 for severity of child social anxiety, ΔF(1, 98) = 6.23, ΔR2 = 0.04, p = .02, and harm avoidance, ΔF(1, 98) = 5.51, ΔR2 = 0.04, p = .02, but not separation anxiety, physical symptoms, or generalized anxiety.

Regarding the roles of child sex and age in these moderation effects, neither child sex nor age remained significantly associated with child anxiety symptoms (total or any specific dimension) after accounting for the effects of FA-Participation, AS, and their interaction. Similarly, child age was not significantly associated to child anxiety symptoms after accounting for the effects of FA-Modification, AS, and their interaction. Child sex remained significantly associated with higher child anxiety symptoms (total and all specific dimensions) even after accounting for the effects of FA-Modification, AS, and their interaction.

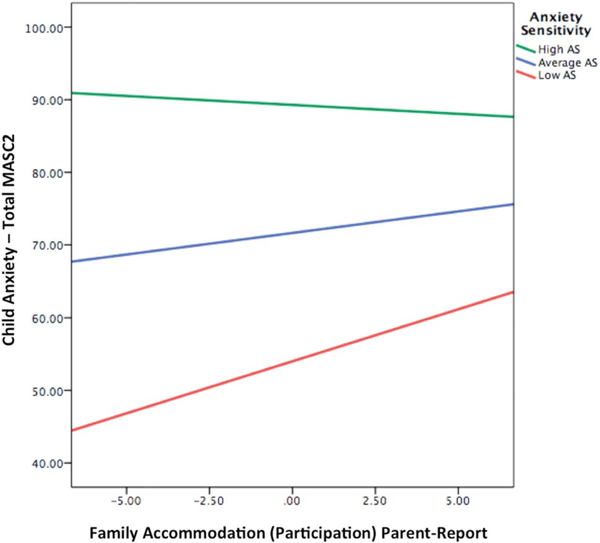

Moderation by AS: Mother-Report FA

Based on mother-rated FA, the interaction between FA-Modification and AS produced a non-significant change in R2 for total child anxiety symptoms, ΔF(1, 98) = 0.10, ΔR2 = 0.00, p = .75. However, the FA-Participation × AS interaction also produced a significant change in R2 for total child anxiety symptoms, ΔF(1, 98) = 4.77, ΔR2 = 0.02, p = .03. Figure 2 illustrates the simple effects (regression lines) for this pattern. Consistent with results based on child-reports of FA, the relation between mother-rated FA-Participation and child total anxiety was strongest among low-AS children [β = 1.43, t = 2.63, p = .009, 95% (0.35, 2.51)] and non-significant for average-AS children [β = 0.59, t = 1.57, p = .12, 95% CI (−0.15, 1.34)] and high-AS children [β = −0.25, t = −0.46, p = .64, 95% CI (−1.30, 0.81)]. We conducted additional hierarchical regressions to test whether this effect was specific to anxiety dimensions based on MASC2 subscales. The FA-Participation × AS interaction produced a significant change in R2 for severity of child social anxiety, ΔF(1, 98) = 4.60, ΔR2 = 0.03, p = .03, but not for any other anxiety subtypes.

Fig. 2.

Child anxiety sensitivity moderates relations between parent-reported family accommodation (participation) and overall child anxiety symptom severity

Regarding the roles of child sex and age in these moderation effects, neither child sex nor age remained significantly associated with child anxiety symptoms (total or any specific dimension) after accounting for the effects of mother-rated FA-Participation, AS, and their interaction.

Discussion

The present study is the first to examine AS as a potential moderator of the FA-child anxiety link in a clinically anxious child sample using mother and child ratings of FA. We examined two plausible, alternative hypotheses. One was that the FA-child anxiety severity link would be stronger for high-AS children than low-AS children. The other was that this link would be stronger for low-AS children than high-AS children. Results supported the latter hypothesis: FA was significantly associated with higher anxiety symptom severity in low-AS children but not high-AS children.

Although studies have suggested that maladaptive family patterns are associated with anxiety symptoms in high-AS children [19], FA differs from previously explored family factors (e.g., parent anxiety, parent hostility) in a critical way. FA most often leads to short-term alleviations in child anxiety. Thus, FA may operate in the typically observed fashion for low-AS children by alleviating child anxious distress in the short term, while inadvertently exacerbating anxiety in the longer-term. In high-AS children, FA may be less effective in alleviating anxious distress because of the children’s focus on, and negative cognitions about, internal anxiety-related sensations. Thus, high-AS children may experience distress in the face of anxiety-provoking stimuli regardless of their parents’ accommodation attempts. Experimental research is required to explore this possibility directly.

Relatedly, FA may differentially influence avoidance behaviors, which often underlie and help maintain anxiety symptoms and disorders, in low-versus high-AS children. Given their lower levels of a cognitive vulnerability that renders anxious feelings and thoughts particularly aversive, low-AS children may be less internally motivated to avoid threatening stimuli. Thus, environmental factors may emerge as primary contributors to these children’s tendencies to avoid (versus approach) stimuli they view as threatening. In contrast, avoidance behaviors in high-AS children may vary less as a function of external factors like FA.

The AS-anxiety severity link was significantly moderated by both parent- and child-reports of parental participation in child symptoms, though only by child reports of parental modification of routines. This pattern may have resulted, in part, from significantly higher mean levels of participation than modification in this sample. Previous research has also found participation is the more common form of FA in parents of children with anxiety disorders [2]. There are likely many more chances each day for parents to participate in their children’s symptoms (e.g., provide reassurance) than to modify routines (e.g., cancel a family vacation). This could create greater opportunity for parent participation, as opposed to parent modification, to shape the AS-anxiety severity link. Additionally, our use of child-report assessments for AS and anxiety symptoms may have increased the likelihood of detecting significant moderation effects based on child-rated FA as compared with parent-rated FA. Future research incorporating parent- and child-reports of FA subtypes may help ascertain the respective influences of participation and modification on AS and anxiety severity in children.

Regarding specific domains of anxiety, AS moderated the link between FA and severity of social anxiety (across informants); separation anxiety (based on child-rated FA); and harm avoidance (based on parent-report FA). In all cases, the FA-child anxiety link was strongest among low-AS children. These results contrast with our hypothesis that the moderation effect would be strongest for somatic symptoms because of their association with panic disorder. It is possible that the association between AS and panic is so robust that FA is unable to account for additional variance in symptom severity. Indeed, in the present sample AS showed high correlations with both physical symptoms and generalized anxiety symptoms, whereas correlations between AS and separation anxiety, social anxiety, and harm avoidance were somewhat smaller. These weaker associations indicate that AS alone could not fully account for variability in these symptom domains, and that they may be further influenced by environmental factors, such as FA. Behavioral avoidance is a core component of separation anxiety, social anxiety, and harm avoidance, providing ample opportunity for FA to exacerbate symptoms in these domains.

The robust, cross-informant moderating effect of AS on the FA Participation-child social anxiety link is especially notable. In past studies exploring FA and child anxiety, direct associations between FA and social anxiety symptoms have been modest to non-significant [4, 8]. Our findings suggest FA may be more strongly associated with social anxiety symptom severity, but only in children with low levels of AS. Similar to Watt et al.’s study on parental reinforcement of sick-role behavior [18], parental participation in child social anxiety symptoms (e.g., speaking for the child in public places) may constitute learning experiences that systematically reinforce the child’s social anxiety. These learning experiences may exert especially powerful impact on socially anxious children with fewer internal predispositions toward avoidance. Future research should continue to parse the circumstances under which FA is linked with more severe child anxiety across disorders.

The roles of child age and sex also merit comment, given both variables’ links to anxiety symptom severity, AS, and potentially, FA. Consistent with previous research, girls reported higher anxiety symptom severity and higher AS than boys, and younger children reported more severe separation anxiety symptoms than did older children [25, 26]. Girls also reported higher levels of FA-Participation, and younger child age was linked with higher FA-Participation across parent and child informants. Despite these associations, neither child sex nor child age remained significantly associated with child anxiety symptom severity after accounting for the effects of FA-Participation, AS, and their interaction, across parent- and child-reports of FA. This result suggests the applicability of the observed moderation effects regardless of child sex, and across a wide child age range. Research on child age and sex differences in FA has yielded mixed results overall, however [2, 8]; further research may help clarify whether and when FA differs by child age and gender, as well as the circumstances under which these differences might affect the FA-child anxiety severity link.

The present study has several limitations. First, because data were collected at a single time-point, causality and directionality of effects cannot be established. Longitudinal research is needed to investigate the temporal and causal pathways, and the likely reciprocal effects between AS and FA in relation to child anxiety. Second, as in most child psychopathology research, this sample focused on mothers. Additional work including mothers and fathers will clarify possible parent-specific effects. Third, we were unable to assess moderation effects as a function of child diagnosis due to low proportions of children with certain DSM 5 anxiety disorders. Future studies can assess whether specific diagnostic profiles shape relations between AS, FA, and anxiety symptom severity in children. Third, given the number of statistical tests conducted, the possibility of Type 1 errors cannot be fully discounted. The consistency of results across informants helps allay this concern, but future replications may further strengthen confidence in the observed effects. Finally, this study relied on questionnaire-based measures for all variables of interest. Our use of both child and parent ratings of FA mitigates shared informant variance, and again, the consistent pattern of results across both parent- and child-reports strengthens confidence in the findings. Future studies using observational and behavioral assessments of FA, child anxiety, and child vulnerability factors like AS could enhance our knowledge of relations among these variables [8].

Despite its limitations, this study advances past work by being the first to show a child vulnerability factor, AS, as a cross-informant moderator of the association between FA and child anxiety symptom severity—particularly social anxiety—and the importance of considering AS when working with anxious children and their families. Assessing AS at the start of treatment may help identify children for whom FA is more strongly linked to anxiety symptom severity, and in turn, those children who may be more likely to benefit from FA-targeted treatment approaches. Future studies may assess these possibilities directly, as well as the robustness of observed moderation effects over time and across clinical and community settings.

Summary

High levels of FA, or parental involvement in child anxiety symptoms, is consistently associated with more severe anxiety symptoms in children. However, the strength of this association has varied considerably across studies, indicating the need to identify variables that might modify observed links. The present study is the first to examine AS as a potential moderator of the FA-child anxiety link in a clinically anxious child sample, using both mother and child ratings of FA. We also examined whether moderation effects were consistent across younger and older children, and girls and boys, given potential age and sex differences in levels of anxiety severity and AS. Findings supported AS as a moderator of FA and child anxiety severity, across both mother and child reports of FA. This effect was particularly strong for social anxiety symptoms. Specifically, the FA-child anxiety severity link was significant for low-AS children, but not for high-AS children. All moderation effects held even after accounting for the effects of child age and sex on child anxiety severity. Findings suggest the value of assessing AS across research and clinical settings in order to identify clinically anxious children for whom FA might be more closely tied to anxiety symptom severity.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (Grant No. KL2TR000140) and National Institute of Mental Health (Grant Nos. K23MH103555, F31MH10820).

References

- 1.Flessner CA, Freeman JB, Sapyta J et al. (2011) Predictors of parental accommodation in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder: findings from the Pediatric Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Treatment Study (POTS) Trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:716–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebowitz ER, Woolston J, Bar-Haim Y, Calvocoressi L, Dauser C, Warnick E, Scahill L, Chakir AR, Shechner T, Hermes H, Vitulano LA (2013) Family accommodation in pediatric anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety 30:47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebowitz ER, Panza KE, Bloch MH (2016) Family accommodation in obsessive–compulsive and anxiety disorders: a five-year update. Expert Rev Neurother 16:45–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson-Hollands J, Kerns CE, Pincus DB, Comer JS (2014) Parental accommodation of child anxiety and related symptoms: range, impact, and correlates. J Anxiety Disord 28:765–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebowitz ER, Panza KE, Su J, Bloch MH (2012) Family accommodation in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Expert Rev Neurother 12:229–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman WK, Kurtines WM (1996) Anxiety and phobic disorders: a pragmatic approach. Plenum Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 7.Storch EA, Larson MJ, Muroff J, Caporino N, Geller D, Reid JM, Morgan J, Jordan P, Murphy TK (2010) Predictors of functional impairment in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord 24:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lebowitz ER, Scharfstein L, Jones J (2015) Child-report of family accommodation in pediatric anxiety disorders: comparison and integration with mother-report. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 46:501–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagan ER, Peterman JS, Carper MM, Kendall PC (2016) Accommodation and treatment of anxious youth. Depress Anxiety 33:840–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Settipani CA, Kendall PC (2016) The effect of child distress on accommodation of anxiety: relations with maternal beliefs, empathy, and anxiety. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 16:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schleider JL, Weisz JR (2017) Family process and youth internalizing problems: a triadic model of etiology and intervention. Dev Psychopathol 29:273–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiss S (1991) Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clin Psychol Rev 11:141–153 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pina AA, Silverman WK (2004) Clinical phenomenology, somatic symptoms, and distress in Hispanic/Latino and Euro-American youths with anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 33:227–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman WK, Fleisig W, Rabian B, Peterson RA (1991) Childhood anxiety sensitivity index. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 20:162–168 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lebowitz ER, Shic F, Campbell D, Basile K, Silverman WK (2015) Anxiety sensitivity moderates behavioral avoidance in anxious youth. Behav Res Ther 74:11–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scher CD, Stein MB (2003) Developmental antecedents of anxiety sensitivity. J Anxiety Disord 17:253–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein MB, Schork NJ, Gelernter J (2008) Gene-by-environment (serotonin transporter and childhood maltreatment) interaction for anxiety sensitivity, an intermediate phenotype for anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watt MC, Stewart SH, Cox BJ (1998) A retrospective study of the learning history origins of anxiety sensitivity. Behav Res Ther 36:505–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollock RA, Carter AS, Avenevoli S, Dierker LC, Chazan-Cohen R, Merikangas KR (2002) Anxiety sensitivity in adolescents at risk for psychopathology. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 31:343–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adelman CB, Lebowitz ER (2012) Poor insight in pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder: developmental considerations, treatment implications, and potential strategies for improving insight. J Obsessive–Compulsive Relat Disord 1:119–124 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK (2006) Anxiety sensitivity: prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology. J Psychiatr Res 40:691–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter R, Silverman WK, Jaccard J (2011) Sex variations in youth anxiety symptoms: effects of pubertal development and gender role orientation. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40:730–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLean CP, Anderson ER (2009) Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev 29:496–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olatunji BO, Wolitzky-Taylor KB (2009) Anxiety sensitivity and the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review and synthesis. Psychol Bull 135:974–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewinsohn PM, Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn M, Seeley JR, Allen NB (1998) Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol 107:109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zahn-Waxler C, Klimes-Dougan B, Slattery MJ (2000) Internalizing problems of childhood and adolescence: prospects, pitfalls, and progress in understanding the development of anxiety and depression. Dev Psychopathol 12:443–466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chorpita BF, Albano AM, Barlow DH (1996) Cognitive processing in children: relation to anxiety and family influences. J Clin Child Psychol 25:170–176 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weems CF, Hammond-Laurence K, Silverman WK, Ginsburg GS (1998) Testing the utility of the anxiety sensitivity construct in children and adolescents referred for anxiety disorders. J Clin Child Psychol 27:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Der Bruggen CO, Stams GJJ, Bögels SM (2008) Research review: the relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49:1257–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albert U, Bogetto F, Maina G, Saracco P, Brunatto C, Mataix-Cols D (2010) Family accommodation in obsessive–compulsive disorder: relation to symptom dimensions, clinical and family characteristics. Psychiatry Res 179:204–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman WK, Albano AM (1996) The anxiety disorders interview schedule for children for DSM-IV: (child and parent versions). Psychological Corporation, San Antonio [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS (2009) Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clinics N Am 32:483–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.March JS (2013) Multidimensional anxiety scale for children (MASC-2). Multi-Health Systems, North Tonawanda [Google Scholar]

- 34.March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK (1997) The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:554–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weems CF, Costa NM, Watts SE, Taylor LK, Cannon MF (2007) Cognitive errors, anxiety sensitivity, and anxiety control beliefs their unique and specific associations with childhood anxiety symptoms. Behev Modif 31:174–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howell DR (2002) Multiple regression In: Crockett C, Day A (eds) Statistical methods for psychology. Thomson Learning, Pacific Grove, pp 533–601 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V (2002) Analysis of variance frameworks in clinical child and adolescent psychology: issues and recommendations. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 31:130–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]