Abstract

Background

Human reproductive disorders consist of frequently occurring dysfunctions including a broad range of phenotypes affecting fertility and women’s health during pregnancy. Several female-related diseases have been associated with hypofertility/infertility phenotypes, such as recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL). Other occurring diseases may be life-threatening for the mother and foetus, such as preeclampsia (PE) and intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR). FOXD1 was defined as a major molecule involved in embryo implantation in mice and humans by regulating endometrial/placental genes. FOXD1 mutations in human species have been functionally linked to RPL’s origin.

Methods

FOXD1 gene mutation screening, in 158 patients affected by PE, IUGR, RPL and repeated implantation failure (RIF), by direct sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. Plasmid constructs including FOXD1 mutations were used to perform in vitro gene reporter assays.

Results

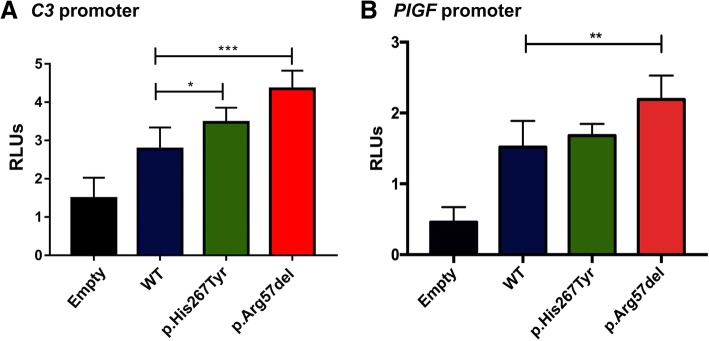

Nine non-synonymous sequence variants were identified. Functional experiments revealed that p.His267Tyr and p.Arg57del led to disturbances of promoter transcriptional activity (C3 and PlGF genes). The FOXD1 p.Ala356Gly and p.Ile364Met deleterious mutations (previously found in RPL patients) have been identified in the present work in women suffering PE and IUGR.

Conclusions

Our results argue in favour of FOXD1 mutations’ central role in RPL, RIF, IUGR and PE pathogenesis via C3 and PlGF regulation and they describe, for the first time, a functional link between FOXD1 and implantation/placental diseases. FOXD1 could therefore be used in clinical environments as a molecular biomarker for these diseases in the near future.

Keywords

Recurrent pregnancy loss, Preeclampsia, Intra-uterine growth restriction, FOXD1

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s10020-019-0104-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Background

Human reproductive disorders consist of frequently occurring dysfunctions including a broad range of phenotypes affecting fertility and women’s health during pregnancy. Several female-related diseases have been associated with hypofertility/infertility phenotypes, most of which can affect the ovaries (e.g. primary ovarian insufficiency-POI), the hormonal system (e.g. polycystic ovary syndrome-PCOS), the fallopian tubes (e.g. obstruction) and/or the endometrium (e.g. recurrent pregnancy loss-RPL- and endometriosis) (Laissue, 2018; Smith et al., 2003). Other commonly occurring diseases may be life-threatening for the mother and foetus, such as preeclampsia (PE) and intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR) both of which causes important physiological changes during pregnancy.

RPL (which affects 2–5% of all pregnancies) has been clinically defined as being at least three pregnancy losses occurring before the 20th week of gestation (El Hachem et al., 2017). Its aetiology is still poorly understood as, although several causes have been described, > 50% of cases are considered idiopathic; such scenario pinpoints the potential participation of a genetic component related to its origin. Various tools have been used for identifying loci and sequence variants related to this disease’s aetiology, such as genome-wide association studies (GWAS), Sanger and next generation sequencing (NGS), linkage analysis and DNA methylation status assessment (Kolte et al., 2011; Li Wang et al., 2010; Pereza et al., 2017; Vaiman, 2015). However, the definitive association of genetic variants or epigenetic modifications with the phenotype has rarely been validated by functional tests.

PE is another frequently occurring disease (~ 5% of pregnancies) which is clinically characterised by pregnancy-induced hypertension and proteinuria, making it one of the main causes of pregnancy-related maternal and foetal morbimortality. Although various pathophysiological mechanisms have been described, PE’s precise aetiology remains unknown (Chaiworapongsa et al., 2014). Identifying early diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers has become a relevant focus for research as PE’s clinical signs and symptoms appear during the third trimester of gestation. More than 15 loci have been mapped and positional cloning has led to interesting PE candidates being identified, such as ACVR2A, TNFSF13B, EPAS1 and STOX1 (Chelbi et al., 2013; Jebbink et al., 2012) (and references therein). STOX1, a transcription factor, has been defined as a key regulator of placental genes and its mutations have been related to PE pathogenesis (van Dijk et al., 2010; Vaiman and Miralles, 2016). Interestingly, Stox1 overexpression in mice has led to placental and endothelial cell dysfunction, PE, IUGR and cardiovascular injury (Collinot et al., 2018; Ducat et al., 2016). Some sequence variants located on additional genes (e.g. SERPINA8, MMP9, VEGF and TNFα) have been found to increase the risk of PE (Chelbi et al., 2013). Regarding IUGR, maternal placental and foetal genes have been proposed as relevant pathophysiology actors (SERPINA3, PlGF, BCL2, BAX, IGF1/IGF2, VEGF, STOX1, FV, SVCAM1 and ADMA) (Sharma et al., 2017).

Interestingly, the participation of common genes and molecular pathways in IUGR, PE and RPL pathophysiology argues in favour of the potential existence of central regulatory actors (e.g. transcription factors) involved in these disorders’ aetiopathology.

A series of studies using a genetic mouse model of interspecific congenic strains allowed us to map quantitative trait loci (QTL) related to embryo resorption (a phenotype analogous to RPL in humans) to short chromosome regions (Laissue et al., 2016, 2009; Vatin et al., 2012). One of these regions was found to contain FOXD1, encoding a forkhead transcription factor, shown to be involved in the regulation of embryo implantation in mice (Laissue et al., 2016, 2009; Quintero-Ronderos and Laissue, 2018). The mouse Foxd1-Thr152Ala variant (carried naturally by the Musspretus species), when expressed in the C57BL/6 J genetic background, was associated to embryo resorption and massive deregulation of the expression of placental and endometrial genes (Laissue et al., 2016). FOXD1 mutations in humans have now been functionally linked to RPL’s origin, thereby constituting a diagnostically useful molecular biomarker (Laissue et al., 2016; Quintero-Ronderos and Laissue, 2018).

Herein, we describe novel FOXD1 gene mutations identified through the screening of 158 patients affected by PE, IUGR, RPL and repeated implantation failure (RIF) following in vitro fertilisation. Nine non-synonymous sequence variants were identified, two of which (p.His267Tyr found in one RIF patient and p.Arg57del in one IUGR woman) represented novel and coherent candidates for in vitro testing. Functional experiments revealed that both led to an increased C3 (complement C3) promoter transcriptional activity. In addition, we found increased FOXD1-p.Arg57del variant transactivation capacity on the PlGF (placental growth factor) promoter. The FOXD1 p.Ala356Gly and p.Ile364Met mutations (previously found in RPL patients) have also been identified in the present work in women with PE and IUGR and with isolated IUGR, respectively.

Our results provide new evidence of FOXD1’s central role in endometrium and placental physiology as we show, for the first time, that besides its involvement in RPL its mutations contribute to RIF, IUGR and PE. FOXD1 could therefore be used in clinical environments as a molecular biomarker for these diseases in the near future.

Methods

Patients and controls

The study population consisted of 158 women suffering from different reproductive disorders: RPL (n = 31), RIF (n = 30), IUGR (n = 39), PE (n = 31), PE and IUGR (PE/IUGR) (n = 27). The RPL and RIF patients were from Colombian origin, whilst those suffering IUGR, PE or PE/IUGR were French (Table 1). The control groups consisted of 203 Colombian and 361 French women lacking a clinical history of reproductive disorders (also see below).

Table 1.

FOXD1 ORF sequencing in RPL, RIF, IUGR and PE patients

| Colombian RPL patients | ||||||||

| DNA | Protein | Rs | Patients | Controls* | MAF (gnomAD)*** | SIFT | PolyPhen | Evolutive conservation |

| c.263C > G | p.Ala88Gly | rs7705335 | 5/31 | 11/203 | 0.1080 | Tolerate (0,52) | Benign (0) | Yes |

| c.308G > A | p.Gly103Asp | rs1369199745 | 1/31 | 2/203 | 0.0000 | Tolerate (0,46) | Benign (0,334) | Yes |

| Colombian RIF patients | ||||||||

| DNA | Protein | Rs | Patients | Controls* | MAF (gnomAD)*** | SIFT | PolyPhen | Evolutive conservation |

| c.263C > G | p.Ala88Gly | rs7705335 | 2/30 | 11/203 | 0,1080 | Tolerate (0,99) | Benign (0) | Yes |

| c.308G > A | p.Gly103Asp | rs1369199745 | 1/30 | 2/203 | 0.0000 | Tolerate (0,46) | Benign (0,334) | Yes |

| c.799C > T | p.His267Tyr | ___ | 1/30 | 0/203 | __ | Deleterious (0,04) | Possibly deleterious (0,69) | Yes |

| c.976G > A | p.Ala326Thr | rs552595262 | 1/30 | 5/203 | 0.0000 | Deleterious (0,07) | Possibly deleterious (0,69) | Yes |

| French IUGR patients | ||||||||

| DNA | Protein | Rs | Patients | Controls** | MAF (gnomAD)*** | SIFT | PolyPhen | Evolutive conservation |

| c.168_170delGCG | p.Arg57del | rs750578392 | 1/39 | 0/361 | 0.0001 | __ | __ | Yes |

| c.263C > G | p.Ala88Gly | rs7705335 | 4/39 | 31/361 | 0.1080 | Tolerate (0,99) | Benign (0) | Yes |

| c.976G > A | p.Ala326Thr | rs552595262 | 1/39 | 11/361 | 0.0000 | Deleterious (0,07) | Possibly deleterious (0,69) | Yes |

| c.1092C > G | p.Ile364Met | rs992724147 | 1/39 | 0/361 | 0.0000 | Deleterious (0) | Deleterious (0,99) | Yes |

| c.1146_1158delCAGGCCGCCGCC | p.Gln383_Ala387delQAAA | rs771204220 | 4/39 | 18/361 | 0.0308 | __ | __ | NA |

| French PE patients | ||||||||

| DNA | Protein | Rs | Patients | Controls** | MAF (gnomAD)*** | SIFT | PolyPhen | Evolutive conservation |

| c.263C > G | p.Ala88Gly | rs7705335 | 6/31 | 31/361 | 0.1080 | Tolerate (0,99) | Benign (0) | Yes |

| c.976G > A | p.Ala326Thr | rs552595262 | 2/31 | 11/361 | 0.0000 | Deleterious (0,07) | Possibly deleterious (0,69) | Yes |

| French PE + IUGR patients | ||||||||

| DNA | Protein | Rs | Patients | Controls** | MAF (gnomAD)*** | SIFT | PolyPhen | Evolutive conservation |

| c.263C > G | p.Ala88Gly | rs7705335 | 1/27 | 31/361 | 0.1080 | Tolerate (0,99) | Benign (0) | Yes |

| c.1067C > G | p.Ala356Gly | rs917127030 | 1/27 | 0/361 | 0.0000 | Deleterious (0,01) | Benign (0,001) | Yes |

| c.1187C > T | p.Pro396Leu | rs540644822 | 1/27 | 2/361 | 0,0042 | Tolerate (0,2) | Benign (0,1) | Yes |

*Colombian controls, **French controls, ***gnomAD v2.1.1 (controls)

Bold data are significant

The unrelated Colombian RPL patients (n = 31) attended the Centre for Research in Genetics and Genomics (CIGGUR-Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia). They had suffered 3 or more consecutive pregnancy losses and had normal 46, XX karyotypes. They had no clinical history of coagulation dysfunction, uterine anomalies, autoimmunity (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome), infection, endocrine and/or metabolic disorders (excluded by biochemical tests). All cases had no background of consanguinity or reproductive diseases.

The Colombian RIF patients (n = 30) were attending the Colombian Fertility and Sterility Centre (Cecolfes, Bogotá, Colombia). The inclusion criteria referred to women having suffered two or more RIF after at least 2 consecutive cycle of IVF or ICSI in which a high-quality embryo had been transferred during each cycle (Rinehart, 2007). β-HCG serum levels were followed-up for monitoring implantation success. Maternal > 40 year-old patients suffering uterine anomalies, miomatosis, hydrosalpinx, having an abnormal karyotype, male-related abnormality factors (e.g. oligospermia, azoospermia), suffering endocrine and coagulation and autoimmunity diseases were excluded from the study.

The French IUGR (n = 39), PE (n = 31) and PE and IUGR (PE/IUGR (n = 27)) patients were attending The Institut Cochin (Paris, France). Inclusion criteria for PE were systolic pressure above 140 mmHg, diastolic pressure above 90 mmHg and proteinuria above 0.3 g per day. The inclusion criteria used for IUGR were reduction of fetal growth during gestation with a birth weight below the 10th percentile according to Lubchenco growth curves. The exclusion criteria included diabetes, chromosomal and fetal malformations, maternal infections, aspirin treatment. The control group for Colombian patients consisted of 203 women (from the same ethnical origin) over 50 years-old having had at least one live birth child without antecedents of medical complications during pregnancy and lacking hypertensive disorders. Regarding the French controls, we used data previously reported by our group (Laissue et al., 2016). In that study, FOXD1 was sequenced in 271 French controls lacking antecedents of obstetrical disorders. In the present study we have increased the amount of French controls to 361 using the same DNA bank. Blood samples were collected from all patients and controls using standard procedures.

All participating individuals signed an informed consent form. All this study’s experimental steps were approved by the Universidad del Rosario’s and Institut Cochin’s Ethics Committees and the study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

FOXD1 sequencing and bioinformatics analysis

DNA was extracted from all patients and controls’ whole blood samples using the salting-out method. FOXD1 amplification and sequencing has been described previously (Laissue et al., 2016). Amplicons were purified using shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I. Internal primers were used for sequencing. The sequences were compared to that of the FOXD1 wild type version (ENSG00000251493). Primer sequences, PCR and sequencing technical conditions have been included as supplementary information (Additional file 1). The novel variants were screened in the gnomAD database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). We also compared the variants’ allele frequencies identified in patients to those from their ethnically-matched controls (Colombian population). SIFT and PolyPhen-2 bioinformatics tools were used for assessing the novel FOXD1-p.His267Tyr missense variant’s potentially harmful effects. FOXD1 proteins from orthologous species (Monodelphis domestica, Pan troglodytes, Sus scrofa, Cebus capucinus imitator, Odobenus rosmarus divergens, Delphinapterus leucas) were aligned to determine potential conservation of His 267 during evolution.

Plasmid constructs and in vitro gene reporter assays

The complete FOXD1 ORF WT and mutant versions (p.His267Tyr and p.Arg57del) were inserted into the pcDNA 3.1 Zeo (+) vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The C3 promoter (− 792 to − 63 bp upstream of the initial ATG start codon) was inserted into pGL4.22[luc2CP/Puro] (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A digestion-ligation protocol was used for FOXD1 and C3 promoter cloning, using 5′-KpnI and XhoI-3′ endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen). The construct containing the PlGF promoter region was previously described (Laissue et al., 2016). All constructs were sequenced to exclude potentially unexpected PCR-induced mutations.

COS-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/Ham’s Nutrient Mixture F12 (DMEM/F12, Gibco) containing 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS-Biowest) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen-Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells were seeded at 50,000 cells/well in 24-well culture dishes and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells were co-transfected using Fugene (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) reagent in a serum-free medium with 800 ng of constructs including the C3 or PlGF promoters, 500 ng FOXD1-WT or mutant versions (c.168_170delGCG; p.Arg57del or c.799C > T-p.His267Tyr) and 30 ng Renilla for 48 h. Negative control involved co-transfection with pcDNA 3.1 Zeo (+) empty vector.

C3 and PlGF transcriptional activities, in response to the WT or mutant versions of FOXD1, were measured 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The luciferase activity reported for each experiment was divided by Renilla activity to obtain RLUs values. Each experiment was repeated three times in sixplicate. Student’s t-test was used for estimating the statistical significance between WT and mutant conditions.

Results

FOXD1 genotyping and bioinformatics analysis

Sequence analysis revealed 9 heterozygous non-synonymous sequence variants (Table 1 gives FOXD1 genotyping results). Among those, four, c.168_170delGCG (p.Arg57del), c.799C > T (p.His267Tyr), c.1067C > G (p.Ala356Gly) and c.1092C > G (p.Ile364Met) were rare as they displayed a very low minor allele frequency (MAF) in public databases of SNPs (e.g. gnomAD). In addition, they were absent in the control group described by Laissue et al., (2016) nor in the present work’s control groups. The c.168_170delGCG (p.Arg57del) and c.799C > T (p.His267Tyr) variants had not been described previously. The p.His267Tyr variant was found in a Colombian RIF patient whilst the p.Arg57del variant was carried by a French IUGR patient. The c.1067C > G (p.Ala356Gly) and c.1092C > G (p.Ile364Met) variants have been previously reported in RPL women (Laissue et al., 2016). Here, one French IUGR/PE patient had the p.Ala356Gly mutation while one IUGR woman carried the p.Ile364Met mutation. The remaining variants were considered to be polymorphisms, having > 1% MAF in the gnomAD SNP database and/or were present in control populations (i.e. 361 French or 203 Colombian women from the present research) (Laissue et al., 2016). SIFT and PolyPhen prediction tools gave scores compatible with a harmful effect for the p.His267Tyr variant (Table 1). This variant’s protein sequence alignment suggested strict His267 residue conservation during the species’ evolution (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Luciferase gene reporter assays

The FOXD1-WT version overexpression allowed to transactivate the C3 and PlGF promoters in luciferase gene reporter assays (C3: WT vs empty vector, 1.9-fold, p = 0.0024; PlGF: WT vs empty vector, 3-fold, p = 1.3 × 10− 5), as reported before by Laissue et al. (Laissue et al. 2016) (Fig. 1). Compared to that of the WT version, the FOXD1 p.His267Tyr and p.Arg57del mutations increased significantly C3 transcriptional activity (1.25-fold, p = 0.03 and 1.5-fold, p = 0.0004, respectively). The FOXD1-p.Arg57del mutation increased PlGF transcriptional activity (1.4 fold, p = 0.002) compared to that for the FOXD1-WT counterpart.

Fig. 1.

Transactivation properties of FOXD1-WT and mutant versions on C3 and PlGF promoters. The FOXD1-WT version overexpression allowed to transactivate the C3 and PlGF promoters in luciferase gene reporter assays (C3: WT vs empty vector, 1.9-fold, p = 0.0024; PlGF: WT vs empty vector, 3-fold, p = 1.3 × 10− 5) (a and b panels). a Compared to that of the WT version, the FOXD1 p.His267Tyr and p.Arg57del mutations increased significantly C3 transcriptional activity (1.25-fold, p = 0.03 and 1.5-fold, p = 0.0004, respectively). b The FOXD1-p.Arg57del mutation increased PlGF transcriptional activity (1.4 fold, p = 0.002) compared to that for the FOXD1-WT counterpart. RLU: relative luciferase units. (*): p < 0.05; (***): p < 0.001

Discussion

IUGR and PE are two complex diseases which are frequently associated with maternal and foetal complications during pregnancy. A clear association between these disorders has been documented, as women suffering PE have an increased risk (up to 4-fold) of being affected by IUGR (Fox et al., 2014; Srinivas et al., 2009). Conversely, IUGR-affected individuals have an increased risk of being affected by PE (Mitani et al., 2009). PE and IUGR share pathophysiological mechanisms affecting the placenta and endometrial tissues, such as hypoxia, thrombosis, ischemia, impaired angiogenesis and inflammation (Armaly et al., 2018; Collinot et al., 2018; Garrido-Gomez et al., 2017; Gurugubelli and Vishnu, 2018; Shamshirsaz et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2017). Several molecular pathways thus become simultaneously dysregulated, which may partly result from the dysfunction of key transcription factors acting in the endometrium and the placenta. Particular interest in FOXD1 has been highlighted as it has been shown to play a central role in mammalian embryo implantation and pregnancy maintenance (Laissue et al., 2016, 2009). FOXD1 mutations have led to embryo resorption in mice and RPL in humans by perturbing transcriptional networks in the endometrium and placenta. It was thus considered that FOXD1 was a coherent candidate gene in the present study as it is potentially related to other female reproductive phenotypes, such as RIF, IUGR and PE.

We focused our attention on FOXD1-p.His267Tyr and p.Arg57del from the 9 non-synonymous sequence variants identified in the present study since they are rare and had not been described previously in RPL women (Laissue et al., 2016) (Table 1). The c.799C > T (p.His267Tyr) variant was carried by a Colombian RIF patient. Since the Colombian population consists of a particular ethnic admixture, and its genetic composition/variability is not widely represented in public SNP databases, we screened this variant in a panel of 203 ethnically-matched controls. The variant was not found in this control population, thereby arguing in favour of an association with the disease’s aetiology. Furthermore, the His267 residue has been conserved during mammalian species’ evolution, strongly suggesting functional relevance (Additional file 1). Accordingly, SIFT and PolyPhen bioinformatics’ prediction tools gave scores compatible with a harmful effect (Table 1). Furthermore, replacing a histidine (His) with a tyrosine (Tyr) has been predicted to be potentially deleterious, since as His is an amino acid which is electrically charged with basic side chains, whilst Tyr is a large aromatic polar uncharged molecule. The p.His267Tyr mutation could thus have led to local or global changes regarding FOXD1’s physiochemical properties, thereby contributing to transcriptional disturbances.

We used a gene reporter system to explore this hypothesis as it facilitated assessing FOXD1’s transactivation capability regarding the C3 and PlGF promoters. C3 belongs to the complement system family of proteins which has at least 50 members and can be activated in several tissues by different mechanisms (Regal et al., 2015). Interestingly, complement factors (including C3) act at the crossroads of endometrium/placenta development and physiology, meaning that they can be considered key molecules potentially involved in various female reproductive disorders (Laissue et al., 2016; Regal et al., 2017, 2015). Recurrent studies in animal models hint to a central effect of C3 deregulation in placental pathophysiology (Girardi, 2018; Girardi et al., 2015; Qing et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012).

In vitro, we showed that the protein’s WT version was able to transactivate the C3 promoter (1.9-fold, p = 0.024) (Fig. 1). The FOXD1-p.His267T and the pArg57del mutations led to statistically significant increases in C3 transcription activity compared to that induced by the WT version. This finding reinforced those described previously for the FOXD1-p.Ile364Met and p.429AlaAla mutations identified in RPL women, arguing in favour of this variant’s functional contribution to the phenotype (Laissue et al., 2016).

High C3 levels have been recorded in women having suffered three pregnancy losses, which might be linked to other inflammatory-related molecules’ local (endometrium and placental tissues) expressional disturbances. Interestingly, increased complement activation has been recorded in human placentas following spontaneous abortion, while CD46 and CD55 (complement regulators) became reduced (Banadakoppa et al., 2014; Regal et al., 2015). Here, we have identified the FOXD1-p.His267Tyr mutation in a RIF patient consistently with the hypothesis that FOXD1 plays an essential role in early pregnancy maintenance. This is consistent with our previous observations where the 66H-IRCS strain of mice (which carries the M. spretus–derived Foxd1-Thr152Ala mutation) presents with high rates of early embryonic death (Laissue et al., 2009).

Regarding the FOXD1-p.Arg57del mutation (which we identified in an IUGR patient), we also considered it as potentially having a functional impact because it had a low MAF in the gnomAD database. Similarly to other harmful FOXD1 missense mutations, FOXD1-p.Arg57del may lead to the protein’s three-dimensional conformational changes and functional disturbances. The FOXD1-p.Arg57del mutation increased 1.5-fold C3 promoter transcriptional activity. Although C3 levels have not been widely studied in women affected by IUGR, due to its relevant role during placental physiology we consider that the transcriptional increase observed in our experiments might also be found in vivo.

FOXD1 has already been shown to be a regulator of PlGF in mice and humans (Zhang et al., 2003, Laissue et al., 2016). We observed increased PlGF transcriptional activity (1.4 fold, p = 0.002) with the FOXD1-p.Arg57del mutation compared to that for the FOXD1-WT counterpart, thereby arguing in favour of a potential placental dysfunction leading to IUGR. Low plasmatic PlGF levels have been reported in PE women and it has been seen that FOXD1 mutations have led to reduced induction capacity on the PlGF promoter in recurrent pregnancy loss patients, whilst PlGF overexpression has been linked to enhanced angiogenesis in tumours (Laissue et al., 2016, Chau et al., 2017 and references therein). These findings and the results of the present work, suggest that fine-tuning PlGF expression is an essential condition contributing to placental/endometrial physiology; indeed its transcriptional dysregulation may contribute to different diseases pathogenesis.

Interestingly, two FOXD1 previously identified mutations (p.Ile364Met, p.Ala356Gly) were re-identified in the present study in IUGR patients. We have previously found them in RPL women and shown that they led to C3 promoter transactivation disturbances (Laissue et al., 2016). Indeed, similarly to that observed in our present FOXD1-p.His267Tyr and p.Arg57del experiments, the FOXD1-p.Ile364Met mutation also increased C3 promoter transcription activity ~ 5 fold (Laissue et al., 2016). These findings argue in favour of FOXD1 mutations possibly contributing to IUGR pathogenesis.

Surprisingly, contrary to that observed for the FOXD1-p.Arg57del mutation, FOXD1-p.Ala356Gly has been reported to decrease C3 promoter transcription activity (Laissue et al., 2016). Although complement cascade activation has been observed in PE patients, it has been postulated that the fine tuning of C3 expression may be an important factor regarding physiological gestation in mice and humans (Chow et al., 2009; Laissue et al., 2016; Lynch et al., 2012, 2011, 2008; Regal et al., 2017). C3 expression disturbances (up or down-regulation) due to FOXD1 mutations over/under specific thresholds might therefore contribute to RPL, PE, and/or IUGR. The functional differences amongst FOXD1 mutations might be related to specific physicochemical modifications triggered by particular amino acid changes and/or secondary to regulatory networks’ inherent downstream complexity. It should be also taken into account that other genetic (e.g. variants in other genes) and epigenetic (e.g. imprinting of paternal alleles, or consequences to variable environmental exposures) changes may modify FOXD1 mutations’ phenotypic effect.

Taken together, our results argue in favour of FOXD1 mutations’ central role in RPL, RIF, IUGR and PE pathogenesis via C3 regulation (Laissue et al., 2016). We consider that FOXD1 should be genotyped in larger panels of patients to establish an accurate genotype-phenotype correlation and to justify proposing it as a reliable, clinically useful biomarker.

Conclusions

Taken together, our results argue in favour of FOXD1 mutations’ central role in RPL, RIF, IUGR and PE pathogenesis via C3 regulation [18]. Although several functionally harmful FOXD1 mutations have been described, a well-documented genotype-phenotype correlation remains to be discovered. This should help clinicians in making more accurate diagnosis/predicting several pregnancy-related disorders. Identifying new mutations and their functional impact may lead to using FOXD1 in the near future as a clinically useful biomarker.

Additional files

Supplementary Methods. DNA extraction, FOXD1 amplification and direct sequencing. (DOCX 19 kb)

Figure S1. Interspecific alignment of FOXD1 in vertebrate species. The His267 residue is highlighted in pink. (PDF 417 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- His

Histidine

- IUGR

Intra-uterine growth restriction

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- NGS

Next generation sequencing

- PCOS

Polycystic ovary syndrome

- PE

Preeclampsia

- POI

Primary ovarian insufficiency

- RIF

Repeated implantation failure

- RPL

Recurrent pregnancy loss

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- Tyr

Tyrosine

- WT

Wild-type

Authors’ contributions

PQ, EM, DV, JCG, DF, CE, HM, DAO, EL, PL analysed the data and revised the paper. PL designed and directed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

Grant: CS/ABN062/GENIUROS 019, Universidad del Rosario. Laissue’s Lab was supported by the Universidad del Rosario.

Availability of data and materials

The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All of this study’s clinical and experimental steps were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of both participating institutions (number: DVN021–1-063). The clinical investigation was performed according to the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1996. All of the women had given their informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Paula Quintero-Ronderos, Email: quinteropaula@gmail.com.

Karen Marcela Jiménez, Email: karenmjrom@gmail.com.

Clara Esteban-Pérez, Email: ciesteban@hotmail.com.

Diego A. Ojeda, Email: d.ojeda.msc@gmail.com

Sandra Bello, Email: sbellouyaban@yahoo.es.

Dora Janeth Fonseca, Email: dora.fonseca@urosario.edu.co.

María Alejandra Coronel, Email: aleja.coronelg@gmail.com.

Harold Moreno-Ortiz, Email: harmor73@gmail.com.

Diana Carolina Sierra-Díaz, Email: diana.sierra@urosario.edu.co.

Elkin Lucena, Email: cecolfes@cecolfes.com.

Sandrine Barbaux, Email: sandrine.barbaux@inserm.fr.

Daniel Vaiman, Email: daniel.vaiman@inserm.fr.

Paul Laissue, Phone: +57 1 3474570, Email: paul.laissue@urosario.edu.co.

References

- Armaly Z, Jadaon JE, Jabbour A, Abassi ZA. Preeclampsia: novel mechanisms and potential therapeutic approaches. Front Physiol. 2018;9. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Banadakoppa M, Chauhan MS, Havemann D, Balakrishnan M, Dominic JS, Yallampalli C. Spontaneous abortion is associated with elevated systemic C5a and reduced mRNA of complement inhibitory proteins in placenta. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177:743–749. doi: 10.1111/cei.12371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiworapongsa T, Chaemsaithong P, Yeo L, Romero R. Pre-eclampsia part 1: current understanding of its pathophysiology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:466–480. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelbi ST, Veitia RA, Vaiman D. Why preeclampsia still exists? Med Hypotheses. 2013;81:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow W-N, Lee Y-L, Wong P-C, Chung M-K, Lee K-F, Yeung WS-B. Complement 3 deficiency impairs early pregnancy in mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:647–655. doi: 10.1002/mrd.21013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinot H, Marchiol C, Lagoutte I, Lager F, Siauve N, Autret G, et al. Preeclampsia induced by STOX1 overexpression in mice induces intrauterine growth restriction, abnormal ultrasonography and BOLD MRI signatures. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1399–1406. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducat A, Doridot L, Calicchio R, Méhats C, Vilotte J-L, Castille J, et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction and cardiac hypertrophy in the STOX1 model of preeclampsia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19196. doi: 10.1038/srep19196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hachem H, Crepaux V, May-Panloup P, Descamps P, Legendre G, Bouet P-E. Recurrent pregnancy loss: current perspectives. Int J Women's Health. 2017;9:331–345. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S100817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Nathan S., Saltzman Daniel H., Oppal Sandip, Klauser Chad K., Gupta Simi, Rebarber Andrei. The relationship between preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction in twin pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014;211(4):422.e1-422.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Gomez T, Dominguez F, Quiñonero A, Diaz-Gimeno P, Kapidzic M, Gormley M, et al. Defective decidualization during and after severe preeclampsia reveals a possible maternal contribution to the etiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114:E8468–E8477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706546114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi G. Complement activation, a threat to pregnancy. Semin Immunopathol. 2018;40:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s00281-017-0645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi G, Fraser J, Lennen R, Vontell R, Jansen M, Hutchison G. Imaging of activated complement using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide particles (USPIO) - conjugated vectors: an in vivo in utero non-invasive method to predict placental insufficiency and abnormal fetal brain development. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1017–1026. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurugubelli Krishna R, Vishnu BB. Molecular mechanisms of intrauterine growth restriction. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2018;31:2634–2640. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1347922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jebbink Jiska, Wolters Astrid, Fernando Febilla, Afink Gijs, van der Post Joris, Ris-Stalpers Carrie. Molecular genetics of preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome — A review. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2012;1822(12):1960–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolte AMM, Nielsen HSS, Moltke I, Degn B, Pedersen B, Sunde L, et al. A genome-wide scan in affected sibling pairs with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage suggests genetic linkage. MHR Basic Sci Reprod Med. 2011;17:379–385. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laissue P. The molecular complexity of primary ovarian insufficiency aetiology and the use of massively parallel sequencing. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;460:170–180. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laissue P, Burgio G, L’Hote D, Renault G, Marchiol-Fournigault C, Fradelizi D, et al. Identification of quantitative trait loci responsible for embryonic lethality in mice assessed by ultrasonography. Int J Dev Biol. 2009;53:623–629. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082613pl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laissue P, Lakhal B, Vatin M, Batista F, Burgio G, Mercier E, et al. Association of FOXD1 variants with adverse pregnancy outcomes in mice and humans. Open Biol. 2016;6:160109. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch AM, Eckel RH, Murphy JR, Gibbs RS, West NA, Giclas PC, et al. Prepregnancy obesity and complement system activation in early pregnancy and the subsequent development of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:428.e1–428.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch AM, Gibbs RS, Murphy JR, Giclas PC, Salmon JE, Holers VM. Early elevations of the complement activation fragment C3a and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:75–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fc3afa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch AM, Murphy JR, Byers T, Gibbs RS, Neville MC, Giclas PC, et al. Alternative complement pathway activation fragment Bb in early pregnancy as a predictor of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:385.e1–385.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.10.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani M, Matsuda Y, Makino Y, Akizawa Y, Ohta H. Clinical features of fetal growth restriction complicated later by preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:882–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereza N, Ostojić S, Kapović M, Peterlin B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of genetic association studies in idiopathic recurrent spontaneous abortion. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:150–159.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing X, Redecha PB, Burmeister MA, Tomlinson S, D’Agati VD, Davisson RL, et al. Targeted inhibition of complement activation prevents features of preeclampsia in mice. Kidney Int. 2011;79:331–339. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero-Ronderos P, Laissue P. The multisystemic functions of FOXD1 in development and disease. J Mol Med. 2018;96:725–739. doi: 10.1007/s00109-018-1665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regal JF, Burwick RM, Fleming SD. The complement system and preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19:87. doi: 10.1007/s11906-017-0784-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regal JF, Gilbert JS, Burwick RM. The complement system and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:56–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamshirsaz AA, Paidas M, Krikun G. Preeclampsia, hypoxia, thrombosis, and inflammation. J Pregnancy. 2012;2012:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2012/374047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D, Sharma P, Shastri S. Genetic, metabolic and endocrine aspect of intrauterine growth restriction: an update. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2017;30:2263–2275. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1245285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Pfeifer SM, Collins JA. Diagnosis and Management of Female Infertility. JAMA. 2003;290:1767. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas SK, Edlow AG, Neff PM, Sammel MD, Andrela CM, Elovitz MA. Rethinking IUGR in preeclampsia: dependent or independent of maternal hypertension? J Perinatol. 2009;29:680–684. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaiman D. Genetic regulation of recurrent spontaneous abortion in humans. Biom J. 2015;38:11. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.133777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaiman D, Miralles F. Targeting STOX1 in the therapy of preeclampsia. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:1433–1443. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2016.1253682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk M, van Bezu J, van Abel D, Dunk C, Blankenstein MA, Oudejans CBM, et al. The STOX1 genotype associated with pre-eclampsia leads to a reduction of trophoblast invasion by α-T-catenin upregulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2658–2667. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatin M, Burgio G, Renault G, Laissue P, Firlej V, Mondon F, et al. Refined mapping of a quantitative trait locus on chromosome 1 responsible for mouse embryonic death. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Wang ZC, Xie C, Liu XF, Yang MS. Genome-wide screening for risk loci of idiopathic recurrent miscarriage in a Han Chinese population: a pilot study. Reprod Sci. 2010;17:578–584. doi: 10.1177/1933719110364248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Irani RA, Zhang Y, Ramin SM, Blackwell SC, Tao L, et al. Autoantibody-mediated complement C3a receptor activation contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2012;60:712–721. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.191817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Hong, Palmer Rachel, Gao Xiaobo, Kreidberg Jordan, Gerald William, Hsiao Lili, Jensen Roderick V., Gullans Steven R., Haber Daniel A. Transcriptional Activation of Placental Growth Factor by the Forkhead/Winged Helix Transcription Factor FoxD1. Current Biology. 2003;13(18):1625–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Methods. DNA extraction, FOXD1 amplification and direct sequencing. (DOCX 19 kb)

Figure S1. Interspecific alignment of FOXD1 in vertebrate species. The His267 residue is highlighted in pink. (PDF 417 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.