Abstract

Background

Current coverage of mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries is very limited, not only in terms of access to services but also in terms of financial protection of individuals in need of care and treatment.

Aims

To identify the challenges, opportunities and strategies for more equitable and sustainable mental health financing in six sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries, namely Ethiopia, India, Nepal, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda.

Method

In the context of a mental health systems research project (Emerald), a multi-methods approach was implemented consisting of three steps: a quantitative and narrative assessment of each country's disease burden profile, health system and macro-fiscal situation; in-depth interviews with expert stakeholders; and a policy analysis of sustainable financing options.

Results

Key challenges identified for sustainable mental health financing include the low level of funding accorded to mental health services, widespread inequalities in access and poverty, although opportunities exist in the form of new political interest in mental health and ongoing reforms to national insurance schemes. Inclusion of mental health within planned or nascent national health insurance schemes was identified as a key strategy for moving towards more equitable and sustainable mental health financing in all six countries.

Conclusions

Including mental health in ongoing national health insurance reforms represent the most important strategic opportunity in the six participating countries to secure enhanced service provision and financial protection for individuals and households affected by mental disorders and psychosocial disabilities.

Declaration of interest

D.C. is a staff member of the World Health Organization.

Keywords: Low and middle income countries, mental health, mental health systems, financing

Service and financial coverage for mental health conditions

Addressing the large and growing burden of mental, neurological and substance use (MNS) disorders at the population level via scaled-up implementation of evidence-based treatment and prevention has been repeatedly called for over the past decade, and can be expected to place new resource demands on the health systems of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1–4 These demands include enhanced administration and governance arrangements, additional human resources, upgraded infrastructure, increased access to medicines and strengthened surveillance systems. Financing the budgetary implications of these extra claims on the health system is therefore a pressing policy concern for countries desiring to move towards universal health coverage for their populations in a manner that includes MNS disorders. Previous research studies have generated estimates of the projected costs of scaling up the availability of community-based mental health services in LMIC settings, based on economic analyses of the comparative cost-effectiveness of a range of intervention strategies and packages.1,3,5–7 Such analyses provide essential inputs into making the investment case for mental health as part of national health policy dialogue and system development.4,8 However, these analyses have not directly addressed the key financing question of who will pay for such service expansion and from what sources.

Current coverage of essential mental healthcare in LMICs is very limited, both in terms of access for those in need of services and in terms of financial protection or benefit inclusion.9–11 Such low levels of service and financial coverage are driven by both supply- and demand-side factors. On the demand side, people with these disorders may be unaware of their condition, may not know about appropriate treatment opportunities, may go undetected or may be unwilling to seek help on account of perceived or actual discrimination and stigmatisation. On the supply side, resources made available by governments for the provision of community-based, person-centred mental healthcare services are often very modest; the resources that are made available are typically directed towards more specialised, institutional services that are not easily accessible and are regularly associated with low standards of care or human rights violations.10,12 Without appropriate access to decent services and adequate protection, individuals with mental disorders and their families face a difficult choice: pay out of pocket for treatment of variable and sometimes poor quality – often by cutting other spending and investment, or by liquidating household assets or savings – or go without treatment altogether.

The often high and potentially catastrophic cost to households of securing the health services and goods they need is the fundamental concern underlying the drive towards universal health coverage. Direct, out-of-pocket payments represent a regressive form of health financing – they penalise those least able to afford care – and are an obvious channel through which impoverishment may occur or deepen. Prepayment mechanisms such as national or social insurance represent a more equitable mechanism for safeguarding at-risk populations from the adverse financial consequences of mental disorders. Accordingly, ongoing efforts to move towards universal health coverage are focused not only on improving service access and coverage but also on increasing the proportion of the population covered by some form of financial protection, and the proportion of total costs covered by some form of prepayment, such as an insurance premium.13

Emerald project on mental health system strengthening

Investigation of the economic impact of mental disorders on households, as well as the financial resources and strategies needed to alleviate these impacts and move towards universal health coverage for persons with mental disorders, has been a central element of the recently completed Emerald project (Emerging mental health systems in LMICs).14 This project was carried out in four African countries (Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda) and two South Asian countries (India and Nepal). Alongside other work streams dealing with different health system strengthening components – including governance, integrated care and health information systems for mental health – the Emerald project has pursued a multipronged investigation into mental health financing. To date, very little research has been undertaken to identify appropriate financing strategies for mental health service provision in LMICs; for example, little is known about current financing barriers, opportunities and configurations, and there is scant evidence of different financing options having been weighed up from the respective points of view of equity, efficiency and sustainability.15 Accordingly, the health system financing component of the Emerald project set out to address three interrelated questions: (a) what human, financial and other resources are needed to scale up prioritised services and reduce the existing treatment gap, (b) what are the economic consequences of mental ill health for households, and what is the level of financial protection for people with mental health problems, and (c) how can scaled-up mental health services best be paid for in a way that is feasible, fair and appropriate within the fiscal constraints and structures of different countries?

Aims of the study

The focus of this study is on the last of these financing questions, building on earlier work undertaken by the Emerald project consortium that addressed the other two questions relating to resource needs of scaled-up services and household-level economic consequences associated with MNS disorders.16,17 Specifically, the aim of this paper is to set out an analytical framework and then to identify key mental health financing challenges, opportunities and strategies in the participating countries of the Emerald project. A series of country-specific papers provide a more detailed and nuanced analysis of the policy context, strategic needs and identified financing strategies pertaining to each national context.18,19

Method

Analytical framework for sustainable mental health financing

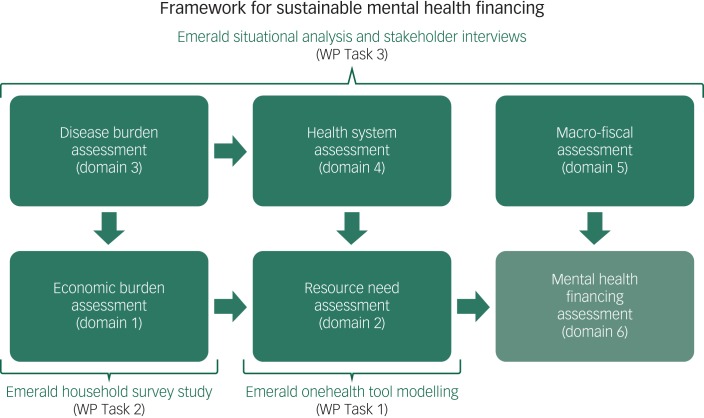

Informed by frameworks developed for other disease priorities in the health sector – such as HIV – the Emerald project developed a streamlined, stepped approach to informing and evaluating country-level financing needs in the area of mental health. Key domains of the Emerald sustainable financing framework include:

assessment of the private and public economic consequences of mental disorders;

assessment of projected resource needs for scaling up mental health services;

assessment of the disease burden of mental disorders;

assessment of the mental health and general health system;

assessment of the current and projected macro-fiscal situation; and

assessment and selection of appropriate financing mechanisms.

As shown in Fig. 1, the Emerald project has undertaken an interrelated series of specific research activities along the pathway to determining strategic financing needs for the future, some already reported. In support of domain 1, assessment of the economic burden of mental disorders has been accomplished via a household survey carried out in the six participating countries, which has provided new information on healthcare expenditures, income and production losses and coping mechanisms of households containing a member with MNS disorder.16 In support of domain 2, information on disease burden and health system capacities has been used to generate estimates of overall resource needs and costs associated with the scaled-up delivery of effective and cost-effective interventions in each of the Emerald countries, which has indicated the level of investment needed to move towards universal health coverage.17 Here in this and the associated country-specific papers, the remaining assessment domains of our framework are analysed.

Fig. 1.

Emerald project's conceptual framework for sustainable mental health financing.

Work package (WP) represents a main element of the Emerald project.

National assessments of disease burden, health system development and macro-fiscal situation

In each country, a detailed situational assessment was carried out to better understand the context, barriers and opportunities for more sustainable mental health financing. These national assessments were structured around several domains, subdomains and key indicators, and were subsequently aggregated into a synthesis report that highlighted strengths and weaknesses of the current system or situation, as well as opportunities for and threats to more equitable and sustainable mental health financing.

Disease burden assessment (domain 3)

Country-specific estimates of the public health consequences of mental disorders were obtained from local prevalence surveys as well as World Health Organization (WHO) global health estimates databases (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/), including rates of prevalence, suicide and disability-adjusted life years.

Health system assessment (domain 4)

WHO's health systems framework was used as a suitable structure for carrying out this assessment, which includes six functions or ‘building blocks’ for health system strengthening: governance; health workforce; financing; service delivery; essential health technologies; and information systems.20 Application of this framework to the mental health (and overall health) situation of each country provides relevant contextual information and raises important questions for sustainable financing, such as whether a strategic vision for the future of mental health system and service development is in place and, if so, whether appropriate laws and resources have been committed to enable its realisation. Each country's overall health system as well as mental health system was described and characterised, informed by nationally available reports and other documentation available through Ministries of Health, Finance and other relevant government departments concerning governance (policies, plans and laws), service availability and access (service organisation, programming and delivery), and financing, as well as health status or outcomes. Particular attention was given to understanding overall health expenditure trends and the contributions made by households towards the cost of healthcare, with reference made to WHO's global health expenditure database (http://www.who.int/health-accounts).

Macro-fiscal assessment (domain 5)

A further level of assessment involved building up an understanding of the broader macro-fiscal context within which scale-up plans and activities are to take place. A country that is experiencing and expecting a prolonged period of economic growth, with manageable levels of indebtedness and a robust tax collection system, is likely to have a very different set of policy options compared with a country with a stagnant economy and/or one with a high level of indebtedness and reliance on external development assistance. In other words, the former country can be expected to have fewer constraints on public spending and therefore more scope to expand services. Accordingly, measures of macroeconomic performance and progress were collated, including current and projected output (total and per capita gross domestic product (GDP)), levels of borrowing and debt (as a percentage of GDP), inflation (year-on-year change in consumer price levels) and (un)employment. Measures of poverty and income inequality provide important complementary information on the distribution of national wealth. Much of the cross-country comparison data were obtained from the World Bank's development indicators database (https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators).

In-depth interviews with health and financing expert stakeholders

A critical phase of development for identifying potentially feasible strategies for more sustainable mental health financing was the conduct of a series of semi-structured interviews with a range of relevant stakeholders. The Emerald project developed an in-depth mental health financing diagnostic tool, which consisted of four semi-structured interview questionnaires that were adapted for local country use to guide the qualitative interviews with key stakeholders (available at https://www.emerald-project.eu/tools-instruments). These stakeholder interviews were designed to: (a) gain a deeper understanding of the processes for (and potential opposition to) health financing reform, including for mental health, (b) validate emerging findings and implications of the (desk-based) national situational assessments, and (c) activate a participatory, consensus-building approach towards the articulation of sustainable financing mechanisms for mental health services in each country. Findings from the in-depth interviews were grouped under three overarching themes: (a) perceived challenges/constraints (to increased public health financing, including for mental health); (b) options for change (for increased financing for public health including mental health); and (c) key elements/criteria (for improved public health financing, including mental health).

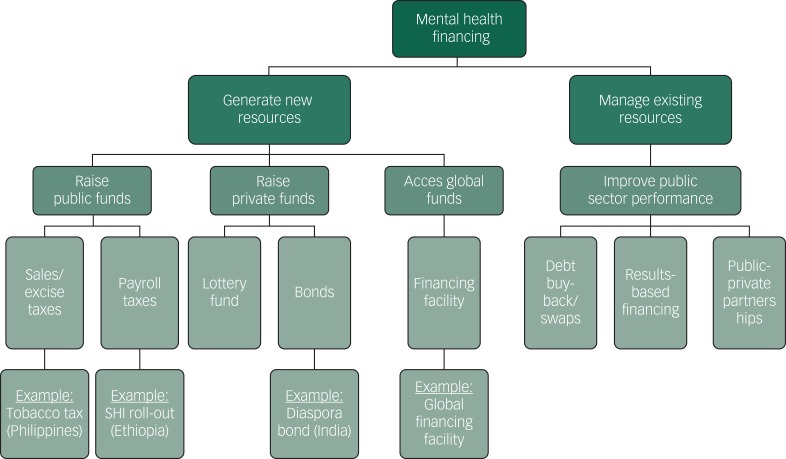

Identification of sustainable financing mechanisms

Findings and insights from the national assessments and in-depth interviews, together with other accrued project evidence and information relating to resource needs for scale up and the extent of inadequate mental health service access or coverage on household welfare, enabled country teams to identify a set of options for moving towards more sustainable mental health financing (domain 6 of the framework). A generic mental health financing algorithm was developed by the project team to facilitate identification of the main possible mechanisms through which new or existing resources for mental health could be realised (Fig. 2). This algorithm was then populated and adapted as required by the country teams. Emerging options were subsequently subjected to a set of criteria to better isolate those with the greatest utility and feasibility, including: the potential for raising revenue (for health and mental health); the potential for increased equity and financial/social protection; the potential for stable and/or sustainable financing; feasibility (cost, implementation, political acceptability); and links to or integration with other priority health programmes (for example maternal and child health, non-communicable diseases).

Fig. 2.

Emerald project's mental health financing algorithm.

SHI, social health insurance.

Results

Detailed findings from each country's analysis of the current situation, interviews with in-depth stakeholder and assessment of potential strategies are provided in separate country-specific reports.18,19 Here, we provide a cross-country comparison of key quantitative indicators underpinning the situational assessments, followed by a qualitative summary of the main challenges, opportunities and strategies for equitable and sustainable mental health financing identified by country teams.

National assessments of disease burden, health system development and macro-fiscal situation

Disease burden assessment

Emerald countries vary with respect to their access to nationally derived estimates of the prevalence of mental disorders. India, for example, recently completed a national mental health survey across 12 states,21 and Ethiopia, South Africa and Nigeria have each carried out nationally representative epidemiological studies of mental disorder or distress in the past, but in the low-income countries of Nepal and Uganda there are very limited local data upon which to assess the need for services beyond specific targeted populations affected, for example, by recent conflicts. An alternative – and comparable – source of data comes from global disease burden estimation exercises. Table 1 provides disease burden measures, which reveals that the public health consequences of mental disorders are already significant and steadily growing in all Emerald countries, although to differing degrees. The (age-standardised) suicide rate, for example, varies from 7.2 per 100 000 population in Nepal to more than 15 in India and Nigeria. As a proportion of total disease burden, MNS disorders account for between 3.4% (in Uganda) and 8.3% (in India and Nepal).

Table 1.

Cross-country comparison of disease burden, health system and macro-fiscal indicators

| Indicator | Ethiopia | India | Nepal | Nigeria | South Africa | Uganda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population in 2015 (millions) | 99.4 | 1311 | 28.5 | 182.2 | 54.5 | 39.0 |

| Disease burden indicatorsa | ||||||

| Age-standardised suicide rates (per 100 000) | 12.8 | 16.0 | 7.2 | 15.1 | 12.3 | 12.6 |

| DALYs due to MNS disorders, per 100 000 population, 2015 | 2833 | 3241 | 2818 | 2890 | 3190 | 2753 |

| Change in MNS DALY rate per 100 000, 2005–2015 | +140 | +31 | +180 | +91 | +32 | +61 |

| MNS disorders as % of total DALYs, 2015 | 5.9 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 3.4 | 6.3 | 5.2 |

| Health system indicators (governance for mental health)b | ||||||

| A stand-alone law for mental health | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| If no, mental health integrated into general health or disability law | No | NR | No | Yes | NR | NR |

| Atlas score (0–5) for compliance of law with human rights instruments | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | N/A |

| Current implementation status of mental health policy or plan | Partially | Partially | Partially | No | Partially | No |

| Atlas score (0–5) for compliance of policy with human rights instruments | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | N/A |

| Number of functional mental health prevention and promotion programmes | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| National suicide prevention strategy | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Health system indicators (health financing)c | ||||||

| Total health expenditure (THE) % gross domestic product (GDP) | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

| General government expenditure on health (GGHE) as % of THEd | 58 | 26 | 18 | 17 | 54 | 13 |

| GGHE as % of general government expenditure (Abuja target: 15%) | 6 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 6 |

| Out-of-pocket expenditure on health as % of THE | 38 | 65 | 60 | 72 | 8 | 41 |

| External resources on health as % of THE | 15 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 40 |

| Macro-fiscal indicatorse | ||||||

| Real GDP growth (annual %, 2016) | 7.6 | 7.1 | 0.6 | −1.5 | 0.2 | 4.6 |

| Inflation, consumer prices (annual %, 2015) | 10.1 | 4.9 | 7.9 | 9 | 4.6 | 5.2 |

| Total unemployment as % of total labour force, 2015 | 5.7 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 5 | 25.9 | 2.3 |

| General government revenue (% GDP) | 16.3 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 9.2 | 29.0 | 14.3 |

| General government total expenditure (% GDP) | 19.1 | 26.8 | 20.8 | 10.9 | 32.4 | 18.9 |

| General government gross debt (% GDP) | 21.8 | 63.3 | 22.3 | 11.2 | 48.2 | 40.0 |

DALYs, disability-adjusted life years; MNS, mental, neurological and substance use; NR, no response; N/A, not applicable.

Source: World Health Organization (WHO) Global Health Estimates, 2015 (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease).

Source: WHO Mental Health Atlas, 2014 (http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles-2014).

Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure database, 2015 (http://www.who.int/health-accounts).

Includes funds received from external donors or international partners.

Source: World Bank development indicators, 2015 (https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators).

Health system assessment

Detailed assessments covering governance, service provision and financing arrangements are given in the country-specific reports; here, only a selection of comparable summary indicators of mental health system governance and financing are shown for the six countries, but these alone provide important insights regarding the prospects for scaled-up mental health service delivery and investment (Table 1).

Concerning governance, only India and South Africa have a stand-alone mental health law, while current implementation of the national mental health policy or plan is rated by all countries as partial at best. The absence of any government-endorsed policy, plan and law for mental health – as is the case in Uganda for example, where such documents have long been drafted but never passed – indicates a weak environment in terms of attracting domestic or external financing for mental health service development. Inspection of health expenditure data across countries likewise provides clear pointers concerning the priority accorded to health in general, and the ability or willingness of governments to protect their citizens against the financial costs and potential hardship associated with the consumption of healthcare services and products. As shown in Table 1, Uganda and South Africa devote a considerably higher proportion of their GDP to health (7–8%) compared with other countries such as Ethiopia, India and Nigeria (4%). In South Africa, the main source of funding for this healthcare expenditure comes from the government (over 50% of the total), but elsewhere there remains a heavy reliance on private, out-of-pocket spending (40–70% of total health expenditures) and in the case of Ethiopia and Uganda, external sources of funding. South Africa alone is close to meeting the Abuja target of directing at least 15% of general government expenditure to health.

Macro-fiscal assessment

Some of the Emerald countries are currently experiencing strong economic growth of more than 5% per annum (Ethiopia and India), whereas others are stagnating or even in recession (Nepal, Nigeria, South Africa). A concern for some countries is the low revenue base that the government enjoys (notably Nepal, where it is below 10% of GDP) and the fact that government spending exceeds these revenues (all Emerald countries are running a deficit apart from Nepal). However, levels of unemployment are modest (<6%) except for South Africa where it has reached over 25%.

Identification of sustainable financing mechanisms

Key strategies for moving towards more equitable and sustainable financing, and therefore universal health coverage, for people with mental disorders are shown in the Appendix, along with a synthesis of the main contextual challenges and opportunities to which they respond.

Key challenges and opportunities

Based on the findings from the situational analysis, Emerald country teams identified key challenges facing the financing and provision of mental health services. The highlighted challenges resonate strongly with those already repeatedly articulated in the global mental health literature, namely a lack of prioritisation given to mental disorders and their prevention or treatment, leading to low levels of resource allocation and consequently large gaps in service availability and effective service coverage. A further common point of concern raised was that the overall sparsity of local mental health services leads to large inequalities in access, indicating that the poorer sections of society are particularly affected by their lower ability to pay for services (which are available only in remote specialist centres of care, especially in country contexts with high out-of-pocket spending levels). The high level of poverty existing in the populations of all Emerald countries generally was a further commonly identified concern and challenge. Weak economic growth, outdated legislation and inadequate information systems were also highlighted by some countries. On the positive side, assessment teams from several countries were able to point to renewed political interest or commitment to mental health service development, for example following the earthquake disaster in Nepal or as shown by the ratification of new mental health legislation in India. A number of country teams also identified relatively favourable economic conditions as a result of buoyant growth (for example Ethiopia) or public financing commitments (for example South Africa).

Emerging issues and insights

The in-depth stakeholder interviews confirmed many of the findings arising from the situational analysis concerning the inadequate levels of priority and funding accorded to mental health services, but also provided relevant new insights concerning existing barriers to change and how to overcome them. For example, senior health policy experts explained the gravity of other public health challenges in their countries, such as rates of HIV/AIDS in South Africa and Uganda, and the difficulties of adding or aligning priorities for overseas development assistance (for example for donors without an explicit focus on mental health). The issue of underutilisation of funds was also identified in the context of India and Nepal; the main challenge in India is not too few funds but a low utilisation rate of allocated funds, whereas in Nepal more funds are certainly needed but concerns were raised with respect to local capacity to absorb them. Expert stakeholders were in broad agreement that national health insurance provided an important opportunity for greater mental health service and financial coverage, and that demonstration of the link between mental disorders and prioritised programmes such as maternal health or other non-communicable diseases offered a strong basis for successful advocacy.

Proposed mental health financing strategies

The principal modes of health financing can be categorised into domestic financing (such as tax-based national health insurance schemes, as well as private, out-of-pocket spending), bilateral/multilateral funding (such as global funds for health) and other more innovative forms of financing (such as lottery funds or pay-for-success mechanisms such as social impact bonds). The pursuit of any of these modes of financing will be influenced by a number of considerations, including the amount of investment needed, the level of political will to raise new resources for health, the amount of fiscal space for raising new resources for health, eligibility for/availability of bilateral/multilateral funding and readiness/willingness to enter into innovative types of market-based financing.

Although there is appreciable variation across Emerald countries in terms of the actions that are proposed, as described in the country-specific analyses, there are also a number of recurring strategies, most notably the inclusion of mental health within planned or nascent health insurance schemes; this was identified as a key need in all six countries. Many of the Emerald countries are already moving forward with an overall reform of their national health insurance schemes, so the explicit inclusion of mental health conditions within this reform process was considered a critical pathway towards sustained and more integrated financing of mental health services. Other means of securing additional domestic resources for mental health – such as increased excise taxes on tobacco and alcohol products – were regarded as having less likelihood of success. With respect to external financing, the low-income countries of Ethiopia, Nepal and Uganda all recommended renewed engagement with new as well as existing development partners in the area of mental health, but stressing the need for a strong investment case as well as governmental buy-in. The Nigerian team proposed to leverage new support from the World Bank and the European Commission for mental health and psychosocial support in the conflict-affected North-East of the country.

In addition to securing new funding from domestic or external sources, more efficient and appropriately targeted use of existing resource allocations can also markedly improve the flow of funds towards the mental health system goals of increased service coverage and financial protection. A number of strategies were identified by country teams, including: better integration of mental health into primary care guidelines and practice (Ethiopia and Nigeria); higher utilisation of existing budgets via improved planning, capacity building or public–private partnerships (India and Nepal); introduction or exploration of performance- or results-based financing measures, such as through remuneration incentives in primary care (South Africa). Further explication of these strategies is documented in forthcoming country-specific papers.

Discussion

Methodological developments

Adequate and sustained financing has been described as ‘a critical factor in the creation of a viable mental health system’ and ‘a fundamental building block on which the other critical aspects of the system rest’.22 Across six LMICs in Africa and South Asia, the Emerald project set out to generate new information and evidence about what actually constitutes an adequate level of resourcing, to investigate the extent and impact of inadequate mental health service access or coverage on household welfare, and to explore options for more sustainable health financing in the future.

For the latter stream of enquiry, we developed an analytical framework and a structured, stepped approach to assessment across a range of relevant domains, so that an informed discussion about the most appropriate and feasible mechanisms for meeting the budgetary and other resource needs of scaled-up prevention and treatment could take place. This approach to the identification of financing mechanisms is based on a good understanding of the current and projected threats to public health and economic growth posed by mental disorder disorders; up-to-date knowledge about how well positioned the existing health system is to address and counter this threat (in terms of service delivery, financing and other critical functions); awareness of the wider macroeconomic context within which health and other sectoral development would need to take place; and a clearly articulated resource-needs plan that identifies the level of additional investment required to meet nationally agreed mental health goals and targets. We advocate the use of such an approach in assessing options for more equitable and sustainable mental health financing beyond those who participated in the Emerald project, and have developed a range of tools and materials to facilitate this process, including the mental health module of the OneHealth Tool (available at http://www.avenirhealth.org/software-onehealth.php), a household survey instrument and a mental health financing diagnostic tool (available at https://www.emerald-project.eu/tools-instruments).

Key elements of mental health financing

In terms of policy implications of the study, the broad international effort to embrace the goal of universal health coverage, reflected in national health insurance reforms in Emerald countries, undoubtedly represents the single most important strategic opportunity to secure greater financial protection over the longer term for individuals and households affected by mental disorders and psychosocial disabilities. The exact process through which mental health can be successfully integrated into overall health financing reform processes is of course highly context-specific – and is accordingly addressed in the accompanying series of national reports – but there are a number of generic components and requirements that are likely to be applicable, including a clear statement of need (based on best available data on treated prevalence as well as overall prevalence of prioritised mental disorders), a budgeted resource plan (based on a defined package of evidence-based and cost-effective interventions) and strong engagement and advocacy with partners in and outside government. Five of the six Emerald countries are also partners in the linked Programme for Improving Mental health care (PRIME) research study, which has systematically carried out these steps at the health district level and achieved significant changes in mental health system governance and service delivery as a result.23

Alongside such a move towards greater mandated financial protection, there is also an evident need to demonstrate more effective and efficient use of the resources that are already made available to the mental health sector. Health system strengthening strategies identified by the Emerald project – strengthened governance procedures, enhanced capacities and better monitoring and surveillance – offer appropriate strategies for attaining such systemic improvements.24–26 In particular, there is a need to further develop the case for – and show the benefits of – integrating mental healthcare into community and primary healthcare settings, ideally as part of an integrated chronic disease management approach. The projected impact on health and economic benefits of scaled-up delivery of mental healthcare have been previously documented4,8 but further evidence on the actualised effects of integrated care on patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment and health outcomes is still needed.

Investing in mental health

As identified through the stakeholder interviews, articulation of the investment or business case for mental healthcare represents a necessary component of efforts to enhance the interest and contribution of international partners and donors. Mental health currently makes up an inordinately low proportion of overall development assistance for health (less than 0.5%),27 but could be substantially increased if a clear, cogent and integrated case for investment is made by eligible countries to develop or transform their services in line with international evidence and human rights conventions. Such an investment case has been made at the global level for common mental disorders4 but could be usefully complemented by more contextualised assessments at the national level. The inclusion of mental health within the sustainable development goals provides eligible countries with an important additional justification for meaningful and sustained external support in service and system transformation.28

In summary, in striving to move towards universal health coverage for people with MNS disorders, LMICs need to not only improve access to a set of effective, efficient and affordable interventions, but also to offer protection against the risk of financial hardship for individuals and families affected by mental illness. Since mental disorders pose a threat to households’ well-being and economic viability, governments have a responsibility to ensure that incurred costs of care are largely or entirely met through appropriate financial protection mechanisms. In the participating countries of this project, that mechanism is most importantly through the inclusion of mental health in planned or nascent national health insurance schemes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following individuals who contributed towards one or more aspects of the work: Constanze Friedl (cross-country indicators); Caroline Whidden (cross-country indicators and Ethiopia situational assessment). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. D.C. is a staff member of the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy or views of the World Health Organization, the UK National Institute for Health Research, the University of Cape Town or the South African Medical Research Council.

Appendix.

Overview of country-specific challenges, opportunities and strategies for sustainable mental health financing

| Key opportunities and threats | Emerging issues and insights (in-depth interviews) | Proposed mental health financing strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Ethiopia | ||

|

|

|

| India | ||

|

The main problem is not too few funds but underutilisation of those funds; low prioritisation at this state level; health insurance/coverage for mental, neurological and substance use (MNS) disorders remains low |

|

| Nepal | ||

|

|

|

| Nigeria | ||

|

Low priority and funding for mental health; new policies and laws stuck; link mental health to other priority programmes and associated donors; efficiency in the utilisation of allocated resources need to be demonstrated |

|

| South Africa | ||

|

|

|

| Uganda | ||

|

|

|

Funding

The research leading to these results is funded by the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) under grant agreement n° 305968. S.D. is a PhD scholarship beneficiary funded by the South African Medical Research Council under the National Health Scholars Programme. G.T. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) South London and by the NIHR Applied Research Centre (ARC) at King’s College London NHS Foundation Trust, and the NIHR Applied Research and the NIHR Asset Global Health Unit award. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. G.T. receives support from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01MH100470 (Cobalt study). G.T. is supported by the UK Medical Research Council in relation the Emilia (MR/S001255/1) and Indigo Partnership (MR/R023697/1) awards. C.H. and C.L. are supported by PRIME, which is funded by the UK Department for International Development (201446). G.T., C.H., A.A. and C.L. are funded by the NIHR Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King's College London (GHRU 16/136/54) using UK aid from the UK Government. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. C.H. additionally receives support from AMARI as part of the DELTAS Africa Initiative (DEL-15-01).

References

- 1.Lancet Global Mental Health Group. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet 2007; 370: 1241–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: Scaling up Care for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders. WHO Press, 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 2015; 387: 1672–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, Cuijpers P, et al. Scaling up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016; 3: 415–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm D, Saxena S. Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat neuropsychiatric conditions in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. Br Med J 2012; 344: e609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gureje O, Chisholm D, Kola L, Lasebikan V, Saxena S. Cost-effectiveness of an essential mental health intervention package in Nigeria. World Psychiatry 2007; 6: 42–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strand KB, Chisholm D, Fekadu A, Johansson KA. Scaling-up essential neuropsychiatric services in Ethiopia: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Policy Plann 2015; 31: 504–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caddick H, Horne B, Mackenzie J, Tilley H. Investing in Mental Health in Low-Income Countries. ODI Research Reports and Studies. Overseas Development Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva MJ, Lee L, Fuhr DC, Rathod S, Chisholm D, Schellenberg J, et al. Estimating the coverage of mental health programmes: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol 2014; 43: 341–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornicroft G, Chatterji S, Evans-Lacko S, Gruber M, Sampson N, Augilar-Gaxiola S, et al. Undertreatment of people with major depressive disorder in 21 countries. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 210: 119–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2017. World Health Organization, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization and the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Innovation in Deinstitutionalization: a WHO Expert Survey. World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. World Health Report: Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. WHO Press, World Health Organization, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semrau M, Evans-Lacko S, Alem A, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chisholm D, Gureje O, et al. Strengthening mental health systems in low- and middle-income countries: the Emerald programme. BMC Med 2015; 13: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon A, McDaid D, Knapp M, Curran C. Financing mental health services in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plann 2006; 21: 171–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lund C, Docrat S, Abdulmalik J, Alem A, Fekadu A, Gureje O, et al. Household economic costs associated with mental, neurological and substance use disorders: a cross-sectional survey in six low and middle-income countries. Br J Psychiatry 2019; 5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chisholm D, Heslin M, Docrat S, Nanda S, Shidaye R, Upadhaya N, et al. Scaling-up services for psychosis, depression and epilepsy in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia: development and application of a mental health systems planning tool (OneHealth). Epidemiol Psychiatr Serv 2016; 19: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Docrat S, Lund C, Chisholm D. Sustainable financing options for mental health care in South Africa: findings from a situation analysis and key informant interviews. Int J Ment Health Syst 2019; 13: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ssebunnya J, Kangere S, Mugisha J, Docrat S, Chisholm D, Lund C, et al. Potential strategies for sustainably financing mental health care in Uganda. Int J Ment Health Syst 2018; 12: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. Framework for Monitoring and Evaluation of Health Systems Strengthening. World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-16: Summary. NIMHNS, 2016. (http://www.nimhans.ac.in/sites/default/files/u197/National%20Mental%20Health%20Survey%20-2015-16%20Summary_0.pdf). [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. Mental Health Financing. WHO Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund C, Tomlinson M, De Silva M, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, et al. PRIME: a programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med 2012; 9: e1001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen I, Marais D, Abdulmalik J, Ahuja S, Alem A, Chisholm D, et al. Strengthening mental health system governance in six low- and middle-income countries in Africa and South Asia: challenges, needs and potential strategies. Health Policy Plann 2017; 32: 699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semrau M, Alem A, Abdulmalik J, Docrat S, Evans-Lacko S, Gureje O, et al. Developing capacity-building activities for mental health system strengthening in low- and middle-income countries for service users and caregivers, service planners, and researchers. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2017; 27: 11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jordans MJ, Chisholm D, Semrau M, Upadhaya N, Abdulmalik J, Ahuja S, et al. Indicators for routine monitoring of effective mental healthcare coverage in low- and middle-income settings: a Delphi study. Health Policy Plann 2016; 31: 1100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlson F, Dieleman J, Singh L, Whiteford HA. Donor financing of global mental health, 1995—2015: an assessment of trends, channels, and alignment with the disease burden. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0169384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackenzie J, Kesner C. Mental Health Funding and the SDGs: What Now and Who Pays? ODI Research Reports and Studies. Overseas Development Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]