Abstract

Several Latin American countries have made remarkable strides towards offering community mental health care for people with psychoses. Nonetheless, mental health clinics generally have a very limited outreach in the community, tending to have weaker links to primary health care; rarely engaging patients in providing care; and usually not providing recovery-oriented services. This paper describes a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Critical Time Intervention-Task Shifting (CTI-TS) aimed at addressing such limitations. The pilot RCT was conducted in Santiago (Chile) and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). We included 110 people with psychosis in the study, who were recruited at the time of entry into community mental health clinics. Trial participants were randomly divided into CTI-TS intervention and usual care. Those allocated to the intervention group received usual care and, in addition, CTI-TS services over a 9-month period. Primary outcomes include quality of life (WHO Quality of Life Scale – Brief Version) and unmet needs (Camberwell Assessment of Needs) at the 18-month follow-up. Primary outcomes at 18 months will be analyzed by Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE), with observations clustered within sites. We will use three-level multilevel models to examine time trends on the primary outcomes. Similar procedures will be used for analyzing secondary outcomes. Our hope is that this trial provides a foundation for planning a large-scale multi-site RCT to establish the efficacy of recovery-oriented interventions such as CTI-TS in Latin America.

Keywords: Community Mental Health Services, Psychotic Disorders, Randomized Controlled Trial, Global Health

BACKGROUND

Community care for people with psychoses in Latin America

The Declaration of Caracas in 1990 marked the beginning of a new era in mental health care in Latin America 1, and remains a crucial touchstone for mental health reform in the region. The advent of this era closely overlapped with a political shift toward democratic governments in much of the region. The Caracas Declaration put forth a multifaceted progressive agenda, within which one of the key goals was to shift the major locus of care for people with psychoses and other severe mental disorders from psychiatric hospitals to community settings. As noted in the more recent Lima Declaration 2, several Latin American countries have developed broad societal legislation and made remarkable strides toward offering care in the community. This progress, however, has been uneven across countries 3.

Community Mental Health Centers (CMHCs) are now the primary locale for outpatient treatment of individuals with psychoses in most countries of Latin America 3. Henceforth we use CMHC as a generic term for community locales that offer specialized mental health services for adults with psychoses and other severe mental disorders, although the nature of these services and the terms used to designate them vary somewhat across and within countries of Latin America.

We describe here a pilot randomized clinical trial (RCT) (Registration number: NCT01995864) of a recovery-oriented, task-shifting intervention for individuals with psychosis that was conducted at CMHCs in two Latin American cities: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Santiago, Chile. The goal of this paper is two-fold: i) describe the study protocol of the pilot RCT, and ii) discuss some implementation challenges and lessons learned when implementing it. Although unorthodox in its format, this piece can be of value for those who plan to design and conduct a pragmatic trial of this novel kind of intervention in Latin America and elsewhere in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). By describing what we planned to do and what was finally implemented, we hope to shed some light on the difficulties of such endeavors often face

Both Brazil and Chile are among the most advanced in Latin America with respect to mental health care 3. For instance, Chile now has a minimal number of beds in asylums 4 and Brazil is moving toward that goal 5. In addition, both countries have a growing number of CMHCs and have paid some attention to the links between CMHCs and primary health care. We note, however, that many other countries, such as Panama, Cuba, and Uruguay, have also made substantial and growing investment to facilitate transition from hospital to community care 6. The intervention tested in this pilot RCT was designed to be delivered at CMHCs and to be adaptable for those countries.

Generally, CMHCs in Chile and Brazil, and elsewhere in Latin America, provide basic, crucial clinical services, including medications and psychosocial interventions. Nonetheless, there are still fewer CMHCs than there is need, and even in Chile and Brazil, a single CMHC might be designated to serve hundreds of thousands of people. Partly as a result of their large catchment areas, the services offered tend to have significant limitations, four of which are especially relevant to the design of this RCT. First, they tend to have minimal resources for the provision of “in vivo” community services, that is, services provided outside the clinic in the user’s home or other community settings 7. Second, they face several challenges in providing coordinated care between different types of services (i.e., primary care, other specialized mental health services, emergency services, etc.) 8. Third, they rarely engage (and almost never employ) users themselves (i.e., peer workers) in planning or providing mental health care 9. Fourth, despite the fact that recovery-oriented approaches have been increasingly adopted in many high-income countries (HICs) 10, such services are rarely offered in Latin America and in no way are they part of universal health care services. In this context, a recovery-oriented approach focuses on expanding the ability of people to rebuild a positive sense of self and social identity despite the challenge of continuing to deal with mental health problems or related disabilities 11. Engagement in this process does not require full remission of symptoms or absence of deficits.

A series of studies has rigorously documented some of these limitations in Chile and Brazil 12–14. In Chile, nationwide studies of psychosocial interventions offered by CMHCs to serve users with psychoses found that only a minority (<25%) were receiving any systematic evaluation or plan for psychosocial intervention 12. Similar findings were reported in Brazil in a systematic review that included 35 studies on mental health service assessment 13. Most reports highlighted the lack of training among professionals at CMHCs to provide outreach interventions and coordinate mental healthcare with primary care and other services. Also, a study that evaluated 21 CMHCs in Sao Paulo reported that almost none included users or ex-users (as peers) in the provision of mental healthcare 14.

Nevertheless, there is progress. The pace might well be accelerated by leveraging the World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 15 in conjunction with the 2016 Lima Declaration on mental health reform in the Latin American context 2. For example, Chile and Brazil have legislated the provision of disability payments and free clinic services for individuals with mental illness, and have legally mandated that mental health services should promote social integration 16,17. At the same time, a small but rapidly growing advocacy movement of users and their families is applying pressure for these mandates to be enforced 6. Another signal development is the widespread improvement in primary health care systems, again with Chile and Brazil playing leading roles. The growing infrastructure of mental health and primary health clinics and the legislative and political environment create favorable conditions for widespread implementation of improvements in community care. The intervention tested here, as described below, was built upon this advantageous platform.

CTI-TS to strengthen community care and promote recovery

This pilot RCT of Critical Time Intervention-Task Shifting (CTI-TS) was conceived as a crucial step toward a broader objective of encouraging regional efforts to address the aforementioned limitations in community care. One of the reasons for conducting the trial in two urban areas was to verify that CTI-TS is applicable to the marginalized poor urban communities where many people in Latin America reside.

The RCT was conducted under the auspices of “RedeAmericas”, a Regional Network for Mental Health Research in the Americas (NIMH U19MH095718). RedeAmericas is one of five such “collaborative hubs” funded by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in Latin America, Africa, and South Asia. A key feature of all hubs was the inclusion of a task-shifting component where non-professionals would be involved in the delivery of mental health services. RedeAmericas brought together an interdisciplinary group of investigators from urban centers in Argentina (Buenos Aires, Córdoba, and Neuquén), Brazil (Rio de Janeiro), Chile (Santiago), Colombia (Medellín), and also from New York City in the United States. The investigators at all sites had decades of experience in developing and adapting interventions in a Latin American context. At the time of this project’s initiation, however, no other RCT had focused on community care for people with psychotic disorders in the Latin American context.

CTI-TS had roots in the evidence-based Critical Time Intervention (CTI) used in high-income countries 18. CTI is a well-known, time-limited psychosocial model designed to mobilize support for vulnerable populations during critical periods. Originally developed and tested with individuals during the transition from shelters for the homeless to community housing, CTI has since been applied during many other critical periods, for example, the months following discharge from inpatient psychiatric treatment, the time when a person is first offered services at a mental health clinic, or, when a person first seeks to reconnect with a mental health clinic after a long lapse. The CTI model has been used with different marginalized communities such as veterans, people with mental illness, people who have been homeless or in prison, people who have suffered serious trauma, among other groups. A number of studies, including randomized controlled trials, have demonstrated the effectiveness of the model 18–20 (see a full list of publications here: https://www.criticaltime.org/). A noteworthy finding is that the positive impact of this time-limited intervention can yield sustained benefits.

The formulation of CTI-TS was a joint effort of three RedeAmericas sites: Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, University of Chile in Santiago, and Columbia University in New York. Colleagues from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro had conducted a series of previous studies to implement CTI in Rio de Janeiro: first, qualitative and quantitative studies of service users, their family members, and service providers at mental health clinics 21,22; next, adaptation and translation of CTI informed by these data 23; followed by a study to test feasibility and acceptability 23; and finally, the initial formulation of CTI-TS. The pilot studies included the marginal communities of Rio de Janeiro, where about 30% of the city’s population lives. In these communities, basic infrastructure, such as transportation, is often inadequate; formal jobs are scarce; and violence is endemic 24. Many other urban areas in Latin America include similarly marginal communities. A major challenge in developing the final version of CTI-TS was to ensure that it would be applicable to these marginal communities as well as to the majority of the population.

In the broadest terms, CTI-TS seeks to improve the lives of people with psychoses who lives in the community and receives mental health care at CMHCs. It is delivered by lay Community Mental Health Workers (CMHWs) and Peer Support Workers (PSWs) based in CMHCs and supervised by mental health professionals. In this trial, both the CMHWs and PSWs were paid employees; they worked in pairs, in a synergistic manner that utilized their distinct capabilities and expertise. CTI-TS addresses the four limitations of existing CMHC care noted earlier by: i. providing in vivo community services, ii. enhancing ties between care provided by primary care centers for general health conditions and secondary mental health center care for mental disorders, iii. using paid peer support workers to deliver mental healthcare; and iv. offering recovery-oriented services. It is offered at a crucial point of transition, that is, at the time of entry into mental health services. Finally, CTI-TS is designed to be a readily adaptable, short-term intervention with a lasting impact, having the potential to improve community care across a wide swath of the region. In a context of limited resources, a 9-month intervention can be scaled up to reach virtually all individuals with psychotic disorders.

CTI-TS does not replace usual care but rather complements it. CTI-TS is a 9-month intervention with a hypothesized lasting impact at 18 months. Therefore, its efficacy depends upon sustained improvement. We hypothesized that participants of this pilot RCT who received CTI-TS as compared to usual care alone would show a trend toward improved health-related quality of life and reporting fewer unmet needs at 18 months after the initiation of the 9-month CTI-TS intervention. We also planned to examine secondary outcomes, such as recovery orientation, disability, continuity of care and substance use.

METHODS/DESIGN

Trial design

This pilot RCT was conducted from 2014 to 2017. While the primary data collection for the trial is over, we are still gathering supplementary information from medical records and qualitative interviews about the trial’s implementation. We believe this will enhance our interpretation and understanding of the findings. We hope to utilize such data for the main reports.

Trial participants were randomized to one of the two groups, either usual care plus the CTI-TS intervention (intervention group) or usual care alone (control group), in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by city (Rio de Janeiro: N= 50; Santiago: N= 60).

Settings

In both cities, the trial was conducted in specified CMHCs and their catchment areas, including CMHCs in marginalized communities, as described briefly below. Participants in Santiago were recruited from five CMHCs, which served a population of 1,245,000 inhabitants corresponding to about 18% of Santiago’s population of 7,037,000 million 25. In these catchment areas, the percentage of people living below the poverty line ranged between 20.7% and 42.2% (average estimate for Chile is 20.9) based on a multidimensional measure of poverty that includes education, health, and housing 26. In Rio de Janeiro the participants were recruited from three CMHCs, which were the primary adult mental health services for areas with approximately 2,400,000 residents representing about 37.2% of Rio’s total population 27. The city is characterized by major social and economic contrasts, with some neighborhoods presenting high rates of robbery, violence and poverty, including neighborhoods where some of the participating CMHCs were located 28.

Study participants and recruitment

Originally, we sought to recruit people with psychotic disorders and their primary caregivers. We were unable, however, to recruit caregivers given a series of obstacles in each city such as limited human resources, administrative complications, and contextual barriers such as limited transportation.

Eligibility criteria for Trial Participants

21–65 years of age.

Any psychotic disorder (chart diagnosis) based on ICD-10 criteria including nonaffective (e.g., schizophrenia) and affective psychosis (e.g., bipolar disorder).

No longer than 3 months since the first visit to the CMHC.

Not expressing active suicidal ideation.

Not presenting cognitive or other sensorial impairment which is likely to preclude reliable assessment via our interview procedures.

Recruitment and screening

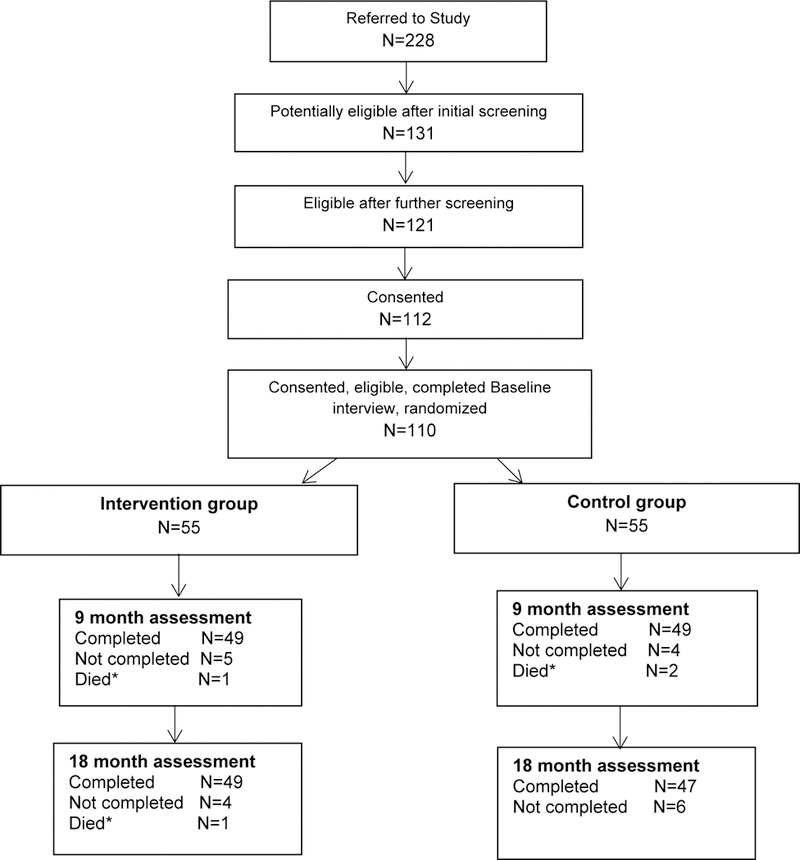

There were 110 trial participants recruited as seen in Figure 1 who were enrolled at five CMHCs in Santiago and at three CMHCs in Rio de Janeiro.

Figure 1. Flowchart of recruitment and allocation.

*Causes of death: lung infection, pulmonary embolism, brain tumor, cardiac event.

Each CMHC designated a CMHC staff member to identify potential trial participants; this person was called the referral professional. When a potential trial participant was identified, the referral professional filled out a referral form and proceeded to conduct a screening interview to confirm eligibility or exclusion. For those individuals who met the inclusion criteria, a CMHC health professional, who was not part of the research team, evaluated capacity for consent by using an adapted form based on the MacArthur competence assessment tool for clinical research (reference). This professional was generally a psychiatrist or psychologist. After capacity for consent was verified, a first contact between the potential trial participant and a research interviewer was scheduled. Research interviewers had also undergone specific training in the protection of human research subjects. In this meeting, the research interviewer verified eligibility and then informed the potential trial participant about the nature of the study, including describing randomized assignment to the intervention or control group, the potential risks and benefits, and the process of evaluation that included assessments at baseline, 9 months’ follow-up and 18 months’ follow-up. The importance of interviewers remaining “blind” to group assignment was explicitly discussed, and participants were asked not to report information that could indicate to which group they were assigned. An unblinded person called ‘registration designee’ was in charge of ensuring the research team (including interviewers) remained blind in each city. His/her tasks included a) handling the ‘randomization log’, which served as the on-site link between the study ID, the randomization assignment, and the information needed to identify the participant such as name, sex, age; b) notifying the intervention team once a participant was randomized to CTI-TS; c) communicating the study ID and name of an incoming participant to the research interviewer; d) examining and reporting any adverse events if that occurred during the trial; and e) reporting any drop outs from the study. This person was trained on NIH guidelines to assure data quality management in clinical research. He/she only used ID/s when talking and communicating with principal investigators and research team in order to maintain the blind. Only she/he had access to the randomization log, which was an encrypted sheet stored in a protected computer in each city.

Randomization and treatment allocation

Sequence generation and allocation concealment

Randomization took place after the baseline interview was completed and eligibility had again been confirmed, using the web-based randomization assignment program provided by the Columbia University Data Coordinating Center (CU DCC). We randomized separately within the study cities to reach good balance between groups (e.g. block randomization) to reduce imbalance (i.e., block randomization). A four-digit study code (henceforth referred to as the study ID) was assigned to each consented trial participant as the basis for collecting de-identified data. The registration designee in each city was designated to enter information in a digital Randomization Log after randomization. When a new participant was randomized to CTI-TS, the local intervention team received a notification containing the trial participant’s name. The intervention team retrieved contact details from the referral professional and kept a confidential list of trial participants assigned to CTI-TS.

INTERVENTIONS

Intervention arm

Personnel: selection and recruitment

The intervention was delivered by pairs who comprised a peer support worker (PSW) and a community mental health worker (CMHW). The approach to selecting and recruiting the paid-PSWs was specially tailored given the novelty of the intervention and was intended to: a) identify potential peers at CMHCs and follow a series of steps to select those most suitable for the role of peer support worker, and b) train those selected before training them together with CMHWs in order to provide them with some advantage and increase personal confidence prior to interacting with CMHWs and mental health professionals.

While the criteria were the same, the process in which the PSWs and CMHWs were recruited and trained in the two sites varied slightly, due to differences in the sociocultural contexts and service systems of the two cities. For instance, the Santiago team opted to recruit PSWs from the CMHCs where the RCT was carried out. Some advantages of this approach were that the PSWs were very familiar with the culture and operations of the CMHCs, had relationships with the CMHC professionals, and resided in the communities served by the CMHCs, where the RCT participants also lived. In Rio de Janeiro, on the other hand, the team decided to recruit potential PSWs from CMHCs that were not included in the trial, and query users’ organizations or groups (e.g., “User’s Voice” and “Transversões”) to propose individuals who might have the potential to become peers for CTI-TS. One advantage of the latter approach was that members of these groups were already familiar with recovery-oriented principles and with ways in which users could assist one another. In terms of recruiting CMHWs, the Santiago team recruited individuals who had no prior formal training in conducting health or mental health interventions. They selected CMHWs based on their experience with and passion for working with vulnerable populations, their familiarity with the areas surrounding the CMHCs and their community services. In Rio, however, CMHWs were recruited from a pool of graduates of a training course at the Escola Politécnica Joaquim Venâncio of Rio de Janeiro for community health workers with previous experience working with people with severe mental illness.

Personnel: training and supervision

CMHWs and PSWs were trained on CTI-TS via a first phase of didactic training and a second phase of on-the-job training which took around 9 months. The training in both phases was guided by a CTI-TS Training Manual that was developed, pilot tested, and then refined over a period of one year 29. The development of the manual posed a series of challenges. For instance, we had to translate the manual from English to Portuguese and Spanish, and vice versa. In other words, we had to standardize concepts across three different languages. Some of those concepts were particularly difficult to translate such as ‘recovery orientation’, given that the word ‘recuperacion’ or ‘recuperação’ had a different meaning in Spanish and Portuguese (e.g., reduction or absence of symptoms). Another challenge related to specifying and distinguishing the core components of CTI-TS from the components that should be adaptable to each setting. That requested several discussions with local stakeholders including CMHWs and PSWs themselves. Our goal was to keep the ingredients that make CTI-TS an effective approach (e.g., shared-decision making) but at the same time add contextual-dependent modifications (e.g., meeting with clients at CMHCs instead of their homes).

The Manual specified the components of CTI-TS that should remain the same across a broad range of contexts; and standardized the process of training for these components. It also specified the components of CTI-TS that could be adapted according to the particular sociocultural context and service system in which CTI-TS is being used.

The didactic phase comprised 54 hours of training sessions. The sessions covered concepts as well as practices, but with a greater emphasis on developing practical skills for CTI-TS. It was followed by on-the-job training with intensive supervision, in which each PSW/CMHW pair conducted the full nine-month CTI-TS intervention with one (Santiago) or two (Rio de Janeiro) users who were eligible for but not included in the RCT.

Ongoing regular supervision of PSWs and CMHWs was a requisite component of CTI-TS. In the RCT, the supervisors were psychiatrists or psychologists. They were trained in CTI-TS by the persons who originally developed it. This occurred over the course of weeklong meetings in New York, Santiago, and Rio de Janeiro over a period of several years.

Participants: CTI-TS intervention.

For purposes of an overview, the intervention can be considered in terms of two broad objectives. One is to help the individual to develop durable connections to support systems. This includes connections to both formal and informal supports, such as mental health services, primary care clinics, family, and friends. The other is to provide practical and emotional support to help the individual to overcome a critical time period of transition during which s/he felt especially vulnerable. The first request for CMHC services generally signified such a critical time period.

In this trial, the work of CTI-TS focused on selected areas identified as crucial to strengthening the individual’s continuum of services and forming enduring links with his or her community supports. As in the original CTI, the role of the CTI-TS worker is specifically designed to avoid becoming the primary source of care for the individual. Also as in the original CTI, the phases of CTI-TS are Initiation, Try-Out, and Transfer of Care. Initiation involves intensive in vivo work and the elaboration of a recovery-oriented plan focused on a few selected areas (eg., family, CMHCs, primary care). Try-out considers lessening involvement and observing how the plan made in the prior phase worked in practice. Finally, Transfer of Care is devoted primarily to ensuring the durability of what was achieved in the previous phases. The user, the CTI-TS workers, and other key formal and informal supports meet to specifically review longer-term responsibilities and goals.

Control arm

Participants: control intervention.

Usual care corresponded to the care that was typically delivered in each city and was provided for both groups (usual care and CTI-TS plus usual care). Usual care was, overall, similar in both cities. For instance, CMHCs in both Rio and Santiago usually 1) served a population enrolled in the public health care system; 2) provided mental health care to adults with psychoses and other severe mental disorders; and 3) had a diverse team of professionals that included psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, and family counselors. CMHCs offered a wide range of services such as psycho-pharmacological treatment, individual psychotherapy and psychoeducation, family therapy, counseling, and, some of them, rehabilitation programs. However, as was stated before, the provision of services outside the clinic was limited in terms of building users’ connections with primary care and community resources 12,14. Providers at primary care, who had some training on mental health, were responsible to identify people with psychosis and refer them to their respective CMHC in each city. CMHCs could also refer users to their primary care centers for more general health and social services, but, as noted above, this was not done sufficiently 13,17.

Fidelity assessment

The fidelity of the intervention was assessed by applying the CTI fidelity scale30. It includes 20 items that evaluate the degree to which providers implemented the key elements of the CTI model. Item-level ratings can be combined to compute an overall fidelity score 30. The score-scale is based on two kinds of assessments: i) quantitative, which includes the quantitative sections of the forms filled out by the CTI-TS team; and ii) qualitative, which were based on the qualitative sections of two of the intervention team forms, as well as on data collected by the fidelity assessors via interviews with the intervention supervisor and fieldwork coordinator and a focus group with the CMHWs and PSWs. The fidelity score uses a 5-point Likert scale (from 1= not at all implemented, to 5= ideally implemented).

Outcomes

A description of assessments included in this trial is provided below (see Table 1). When measures had not been translated and adapted to each context, we translated these from English to Spanish/Portuguese, and vice versa, following the World Health Organization’s guidelines 31. Assessments were conducted by blinded and external interviewers, who had sufficient experience in conducting clinical evaluations. These interviewers received a two-week training, and ongoing supervision, on how to administer and code each measure by our research team.

Table 1.

List of assessments included in the CTI-TS RCT.

| Outcome | Assessment | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of Life | WHO Quality of Life—Brief Version | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Unmet needs | Camberwell Assessment of Needs | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Level of Disability | WHO Disability Assessment | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Recovery Orientation | Recovery Assessment Scale | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Continuity of Care | CONNECT: A Measure of Continuity of Care | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Course of illness | Life Chart Schedule | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Public stigma | Perceived Devaluation and Discrimination | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Internalized stigma | Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness | Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

| Alcohol, smoking, substance use |

WHO Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test |

Baseline, 9 months, 18 months |

Primary outcomes

They are health-related quality of life and unmet needs at 18 months. Further analyses consider changes over time across the three time points of baseline, 9 months, and 18 months for these two outcomes as noted below.

Health-related quality of life was assessed by using the WHO Quality of Life – Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) 32. This instrument has 26 items and measures the following domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment, with two additional general questions. The Camberwell Assessment of Needs (CAN) 33 was used to measure unmet needs. This instrument evaluates 22 areas of need such as accommodation, food, safety to self, among others.

Secondary outcomes

Six secondary outcomes are included in this study: Level of Disability (WHODAS 2.0) 34; Orientation toward self-directed recovery (Recovery Assessment Scale, RAS) 35; Continuity of care and course of illness (CONNECT and the Life Chart Schedule) 36,37; perceived stigma (Perceived Discrimination and Devaluation Scale, PDD) 38 and self-stigma (Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness, ISMI) 39; and substance use (WHO Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test Schedule) 40.

Sample size (based on precision of confidence intervals)

We have calculated our sample size based on the precision (or margin of error) of our estimators. There are three main reasons why we chose to calculate sample size based on precision rather than conventional statistical power. First, the estimation of sample size based on precision is well known in the literature (reference). Second, for pilot trials this method is preferred because our sample size is too small for us to conduct a full powered study. Third, the purposes of this pilot RCT included the estimation of key mission-critical parameters for designing a subsequent regional, phase III RCT. Those parameters include subject accrual rates, retention and attrition rates, prevalence of discrete outcomes, means of continuous outcomes, standard deviations of outcome measures, and, in the case of longitudinal data, intra-class correlations measuring within-subject correlations over time. While the sample size in the pilot study might be too small to estimate the intervention effect adequately, large sample sizes are not required to sufficiently estimate these mission-critical parameters for planning a future RCT with an appropriate sample size based on conventional computation of statistical power analysis.

We describe here how precision was calculated for the WHO-QOL BREF. This formula uses the standard deviation (SD=15) for WHO-QOLBREF as previously reported in the literature and an intra-class correlation coefficient of .01.

If we consider 30 subjects in treatment group in Santiago are correlated No of independent observations in treatment group in Santiago = = 23

Similarly, 25 subjects in treatment group in Rio are correlated No of independent observations in treatment group in Rio = =20

Total number of independent observations per arm = 43

Width of confidence interval* = = 6.3

Data Management and Analysis

Data management

A tracking system was implemented in each city, for recording contacts with participants and caregivers, and tracking the screening process and follow-up procedures. Data from each assessment was recorded on paper forms, and then entered via web-based data entry screens to a secure database built and maintained by the CU DCC. Data entry screens for all instruments were available in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Regardless of site and language of entry, data were transmitted securely via the internet and stored in a SIR/XS relational database maintained by the CU DCC. Online reports updated nightly allowed central and local monitoring of participant accrual, data completeness and study termination as needed for Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reports.

Plan for Data Analysis

We will conduct descriptive analyses including frequency distributions, and measures of central tendency and dispersion with 95% confidence intervals. Bivariate analyses will be based on chi-square, Fisher’ s exact, Student’s t-test or rank-sum tests, as appropriate. We will then perform multiple imputation for missing data by using 20 imputations and a fully conditional model based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo.

Our main analyses of outcomes will be conducted using multiple imputation as described above and the intention-to-treat sample (i.e. based on the group that a participant was allocated in). Primary outcomes at 18 months will be analyzed by using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) with observations clustered within sites. For longitudinal analyses to examine trends over time in primary outcomes (with measures from baseline, 9-month follow-up, and 18-month follow-up), we will use three-level multilevel models, with observations at different times clustered within observations, which are in turn clustered within sites. Similar procedures will be used for analyzing secondary outcomes.

Ethical considerations

This study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Columbia University National, the local IRB at University of Chile, the local IRB at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro local IRB, and the Brazil National Ethical Committee. Additionally, the NIMH Global Mental Health DSMB monitored the study. The role of the DSMB was to ensure that research and intervention team members in Rio and Santiago understood the processes in place to protect the safety of study participants, and to verify that the study protocol and procedures were being followed correctly.

Discussion

We have described the study protocol of a pilot RCT of CTI-TS and some of the lessons we learned while implementing it. To our knowledge, this was the first RCT of a recovery-oriented intervention for people with psychoses conducted in Latin America, and elsewhere in any low-and-middle income country. As noted previously, CTI-TS was designed to address gaps in the provision of mental health care for people with psychoses by providing in vivo community services, promoting continuity of care between health service providers, employing peers and community workers, and promoting recovery-oriented services that encourage empowerment and positive sense of self among people with psychoses despite having certain mental and physical deficits. Although major mental health reforms have taken place over the last years in countries such as Brazil and Chile, recovery-oriented interventions are not generally offered and have not been tested in these countries.

We note the potential value of using non-professionals such as CMHWs and PSWs in the delivery of CTI services and mental health services, more generally. They can offer some of the services delivered by professionals (i.e. medication monitoring), but also provide support and promote recovery orientation among people with psychosis. PSWs in particular have the unique experience of developing strategies to overcome their own mental health difficulties. Therefore, they can provide role modelling in a way that only a person with lived-experience can do. For a vulnerable group such as individuals with serious mental disabilities, the employment of such workers has the potential to facilitate the process of bringing people into social and health services, as well as connecting them with community resources and family members. We hope this trial contributes to legitimize and institutionalize their role in mental health services in Latin America as occurred in the U.S. and some other HICs, where peer services are frequently offered for people with psychoses as part of regular care 41.

Finally, our experience suggests that regionally generated research evidence can be key to dissemination and widespread adoption of effective mental health reforms. Evidence derived from HICs on interventions for people with psychotic disorders often cannot be universally implemented in Latin American countries. Some of these interventions are costly and complex, and/or ill-suited to the service systems and sociocultural contexts of the marginalized communities where so many people live. A regional evidence base would surely be more applicable and likely more persuasive to those who promote and implement mental health policies. As noted above, the RCT of CTI-TS was specifically tailored to help meet this challenge. Our hope is that this trial provides a foundation for planning a large-scale multi-site RCT to establish the efficacy of recovery-oriented intervention such as CTI-TS in Latin America.

References

- 1.Levav I, González Uzcátegui R: The roots of the Caracas Declaration; in Mental Health Care Reform: 15 Years After Caracas [in Spanish]. Edited by Rodriguez J Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC;2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Salud del Perú Ministerio. Regional Conference on Community Mental Health, Lima, 2016. http://www.paho.org/per/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3187:2016-01-05-21-23-09&Itemid=900. Accessed Aug 17, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Informe Regional sobre los Sistemas en Salud Mental en América Latina y el Caribe. 2013. www.paho.org/per/images/stories/FtPage/2013/WHO-AIMS.pdf. Accessed Aug 17, 2017.

- 4.Minoletti A, Sepúlveda R, Horvitz-Lennon M. Twenty years of mental health policies in Chile: lessons and challenges. Int J Ment Health. 2012;41(1):21–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loch AA, Gattaz WF, Rössler W. Mental healthcare in South America with a focus on Brazil: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Psychiatr. 2016;29(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minoletti A, Galea S, Susser E. Community mental health services in Latin America for people with severe mental disorders. Publ Health Rev. 2012;34(2):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldas de Almeida JM, Horvitz-Lennon M. Mental health care reforms in Latin America: an overview of mental health care reforms in Latin America and the Caribbean. Psych Serv. 2010;61(3):218–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldas de Almeida JM. Mental health services development in Latin America and the Caribbean: achievements, barriers and facilitating factors. Int. Health. 2013;5(1):15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stastny P Introducing peer support work in Latin American mental health services. Cad Saude Colet. 2012;20(4):473–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Boutillier C, Leamy M, Bird VJ, Davidson L, Williams J, Slade M. What does recovery mean in practice? A qualitative analysis of international recovery-oriented practice guidance. Psychiatric services. 2011;62(12):1470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson L, O’connell MJ, Tondora J, Lawless M, Evans AC. Recovery in serious mental illness: A new wine or just a new bottle?. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36(5):480. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markkula N, Alvarado R, Minoletti A. Adherence to guidelines and treatment compliance in the Chilean national program for first-episode schizophrenia. Psych Serv. 2011;62(12):1463–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa PH, Colugnati FA, Ronzani TM. Mental health services assessment in Brazil: systematic literature review. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20(10):3243–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nascimento AD, Galvanese AT. Evaluation of psychosocial healthcare services in the city of Sao Paulo, Southeastern Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mateus MD, Mari JJ, Delgado PG, Almeida-Filho N, Barrett T, Gerolin J, Goihman S, Razzouk D, et al. The mental health system in Brazil: Policies and future challenges. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarado R, Minoletti A, González FT, Küstner BM, Madariaga C, Sepúlveda R. Development of community care for people with Schizophrenia in Chile. Int J Ment Health 2012;41:48–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, Felix A, Tsai WY, Wyatt RJ. Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a” critical time” intervention after discharge from a shelter. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):256–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herman D, Conover S, Felix A, Nakagawa A, Mills D. Critical time intervention: An empirically supported model for preventing homelessness in high risk groups. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007;28:295–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman D, Conover S, Gorroochurn P, Hinterland K, Hoepner L, Susser E. A randomized trial of critical time intervention in persons with severe mental illness following institutional discharge. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(7):713–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Souza FM, Valencia E, Dahl C, Cavalcanti MT. A Violência urbana e suas consequências em um centro de atenção psicossocial na zona norte do município do Rio de Janeiro. Saúde Soc. 2011;20(2):363–76. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva TFC, Abelha L, Lovisi GM, Calavacanti MT, Valencia ES. Quality of life assessment of patients with schizophrenic spectrum disorders from Psychosocial Care Centers. J. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2011;60:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tavares Calvacanti M, Araújo Carvalho M, Valencia E, Magalhães Dahl C, Mitkiewicz de Souza F. Adaptação da “Critical Time Intervention” para o contexto brasileiro e sua implementação junto a usuários dos Centros de Atenção Psicossocial do município do Rio de Janeiro. Cienc. Saude Colet. 2011;16(12):4635–4642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lovisi G, Mari J, Valencia E, eds. The Psychological Impact of Living under Violence and Poverty in Brazil. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goverment of Chile . Secretaría Regional Ministerial de Salud de la Region Metropolitana. http://www.asrm.cl/archivoContenidos/poblacion-total-rm-2013.pdf. Accessed Aug 17, 2017.

- 26.Goverment of Chile. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social de Chile http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/casen-multidimensional/casen/casen_2015.php. Accessed Aug 17, 2017.

- 27.da Saúde Ministério . Secretaria Executiva. Informações de Saúde. Saúde Suplementar http://www.ans.gov.br/anstabnet/#. Accessed Aug 17, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendes Ribeiro J, Inglez-Dias A. Políticas e inovação em atenção à saúde mental: limites ao descolamento do desempenho do SUS. Cienc. Saude Colet. 2011;16(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conover S and Restrepo-Toro ME. CTI-TS Training the Trainers Manual. New York; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.da Silva TF, Lovisi GM, Conover S. Developing an instrument for assessing fidelity to the intervention in the Critical Time Intervention–Task Shifting (CTI-TS)–preliminary report. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2014;1:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization (WHO) Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments guidelines. http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/

- 32.The WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychological Medicine, 1998; 28: 551–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phelan M, Slade M, Thornicroft G, Dunn G, Holloway F, Wykes T, Strathdee G, Loftus L, McCrone P, Hayward P. The Camberwell Assessment of Need: the validity and reliability of an instrument to assess the needs of people with severe mental illness. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;167(5):589–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Rehm J, Kennedy C, Epping-Jordan J, Saxena S, Korff MV, Pull C. Developing the World Health Organization disability assessment schedule 2.0. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:815–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corrigan PW, Salzer M, Ralph RO, Sangster Y, Keck L. Examining the factor structure of the recovery assessment scale. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2004;30(4):1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ware NC, Dickey B, Tugenberg T, McHorney CA. CONNECT: a measure of continuity of care in mental health services. Mental health services research. 2003;5(4):209–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Susser E, Finnerty M, Mojtabai R, Yale S, Conover S, Goetz R, Amador X. Reliability of the life chart schedule for assessment of the long-term course of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;42(1):67–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American sociological review. 1989:400–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry research. 2003;121(1):31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Group WH. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chinman M, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, Swift A, Delphin-Rittmon ME. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(4):429–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]