Abstract

The VA Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) provides landmark support for family caregivers of post-9/11 veterans. This study examines PCAFC support for veterans with and without PTSD and assesses whether program effect differs by PTSD status using a pre-post, non-equivalent, propensity score weighted comparison group design (n = 24,280). Veterans with and without PTSD in PCAFC accessed more mental health, primary, and specialty care services than weighted comparisons. PCAFC participation had stronger effects on access to primary care for veterans with PTSD than for veterans without PTSD. For veterans with PTSD, PCAFC support might enhance health service use.

Keywords: Veteran, Family caregiver, PTSD, Mental illness, Department of Veteran Affairs policy, Outpatient service use

Introduction

Family members perform a significant service caring for veterans with severe physical, mental, and cognitive impairments. In the U.S., 1.1 million family members provide care for veterans who served after September 11, 2001 (Ramchand et al. 2014). In recognition of the importance of these individuals to the wellbeing of many veterans, the U.S. Congress enacted P.L. 111–163, the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act of 2010, which established the Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) in the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). The program is a landmark effort to support family caregivers1 of veterans seriously injured in the line of duty on or after September 11, 2001 and improve the recovery trajectory of these veterans. Caregivers enrolled in PCAFC participate in a mandatory training addressing topics related to self-care, caregiving skills, managing challenging behaviors, and VA resources. PCAFC caregivers also receive a stipend, access to mental health services, respite care, and travel support. Further, caregivers without health insurance are eligible for VA healthcare coverage under CHAMPVA (Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veteran Affairs). PCAFC families also receive an initial home visit, quarterly contacts via home, telephone or telehealth, and an annual home visit from VA healthcare providers; during these home-based visits and contacts, providers may give veterans referrals to needed health services. All veteran family caregivers, including those not enrolled in PCAFC, have access to Caregiver Support Coordinators, the Caregiver Support Line, an interactive website, respite care services (benefits are more limited than those awarded to PCAFC caregivers), and mental health services (when indicated as part of the veteran’s treatment plan) (Miller et al. 2015; Van Houtven et al. 2017).

While recent work examined the overall effect of PCAFC participation on veteran service use (Van Houtven et al. 2017) there is also a need to assess whether these effects are different among veteran sub-populations. If specific groups benefit more than others, program administrators and staff can target outreach efforts and tailor program services to meet the needs of groups for whom the program has relatively greater benefits. The present study examines whether there are differences in program effects and access to outpatient services between veterans with a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis compared to veterans without PTSD.

PTSD is highly prevalent (73%) among veterans whose caregivers are enrolled in PCAFC (Van Houtven et al. 2017). Further, research suggests that post-9/11 veterans with PTSD have substantial unmet mental and physical health needs (Elbogen et al. 2013; Tanielian and Jaycox 2008). Veteran-perceived barriers, including negative treatment bias, stigma, and PTSD symptoms (e.g. avoidance) are related to underuse of care (Elbogen et al. 2013; Hoge et al. 2008). Among veterans with self-reported mental health concerns, fewer than half reported interest in seeking mental health care and only 23–40% actually used psychiatric services (Hoge et al. 2008) even though VA provides mandatory PTSD screening and evidenced-based mental health treatment (Karlin et al. 2010). Therefore, many veterans do not receive enough treatment visits to qualify as evidence-based psychotherapy (Seal et al. 2010; Tanielian and Jaycox 2008). Veterans with PTSD also have more physical health needs than veterans without PTSD that require medical care (Frayne et al. 2011; Hoge et al. 2007). Family members might provide instrumental (i.e. care coordination, transportation to medical appointments) (Van Houtven et al. 2011) and emotional support, thereby increasing access to health services and treatment engagement for veterans with PTSD (Gros et al. 2013). Thus, supporting family members of VA-users who meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD is a potential strategy to narrow health service gaps specific to veterans with a PTSD diagnosis.

A few studies have considered the impact of policy interventions for family caregivers on outcomes for care recipients with cognitive limitations and severe mental illness (Van Houtven et al. 2011). However, no literature has examined the effect of such institutional policies and supportive services for family members on health service outcomes of individuals with PTSD in the civilian or veteran population (Shepherd-Banigan et al. 2017). Currently, interventions to support family caregivers are limited to tax credits in certain states, Medicaid Home and Community-based waiver funds (Alliance for the Betterment of Citizens with Disabilities 2016), and small scale training programs (Feinberg and Newman 2006). The PCAFC is the first national effort to systematically provide supports and services to qualifying family caregivers to improve outcomes for care recipients. This study is part of a comprehensive initiative to examine the effect of the PCAFC on caregiver outcomes, including veteran access to service, veteran and caregiver wellbeing, and caregiver perspectives about the use and value of the PCAFC. Papers that present information about caregiver outcomes and perspectives are forthcoming. The present study uses a retrospective study design to examine whether the PCAFC has a differential impact on access to outpatient health services among veterans with and without PTSD. Specifically, this study examines three related questions: (1) is a PTSD diagnosis associated with the probability of receiving mental health, primary care, and specialty care outpatient services among veterans in the sample? (2) is PCAFC participation associated with probability of receiving mental health, primary care, and specialty care outpatient services among veterans in the sample? And, (3) does PTSD diagnosis moderate the relationship between participation in the PCAFC and receipt of mental health, primary care and specialty care outpatient health services?

It is hypothesized that PCAFC participation will increase access to, and therefore use of, outpatient care for individuals with PTSD through several potential mechanisms. First, the mandatory caregiver training might improve the ability of a caregiver to navigate the VA health care system. Second, the quarterly visits and contacts might result in immediate referrals to services for unmet needs. Third, increased access to care for the caregiver might improve his/her health and ability to address the veteran’s service needs. Finally, the stipend might enhance the caregiver’s ability to accompany the veteran to health care appointments. However, it is unclear whether PTSD status will moderate the effect of the program on the probability of receiving outpatient services. Individuals with PTSD have unmet needs (Elbo-gen et al. 2013; Hoge et al. 2008), and moderation could occur if the program specifically targeted mechanisms to address those unmet needs. Moderation could also occur if the groups had different levels of unmet need and the program simply increased the proportion of need that was met in both groups. Veterans with PTSD do use more services than veterans without PTSD (Calhoun et al. 2002; Frayne et al. 2011), but it is unclear whether the two groups differ in terms of unmet needs.

Methods

Study Design, Sampling Frame, and Analytical Sample

This study uses a retrospective, pre-post, non-equivalent comparison group design to examine if PCAFC participation has a differential impact on the odds of outpatient health service use among veterans by PTSD status. Baseline was defined as the date of application to the PCAFC for each veteran and applying caregiver in the study and established the pre-post timeframe in the analytic models.

The sampling frame included individuals who applied to the PCAFC between May 1, 2011 and March 31, 2014; to be included in the treatment group, individuals needed to have applied and been approved by March 31, 2014. Family caregivers are eligible for the PCAFC if they provide care for a veteran family member or friend who sustained serious injury in the line of duty on or after September 11, 2001 and the veteran needs caregiver assistance to perform activities of daily living or needs supervision and protection due to the residual effects of his/her war-related injuries for a minimum of 6 months (Public Law: 111–163). It is probable that veterans with a traumatic injury (e.g. spinal injury, traumatic brain injury) would have co-occurring PTSD and be more likely to require caregiver assistance. Caregivers were denied PCAFC services more often on the basis of administrative (n=4913/8626) as opposed to clinical (3713/8626) reasons, such as caring for a veteran injured before September 11, 2001 or caring for a veteran with an illness not related to military service. Specifically, based on administrative records, of the 8626 individuals denied, 13% were denied because they did not serve in the post-9/11 era and 5.5% were denied because they had a non-service related illness. It is possible that reasons for denial, including not having a qualifying service-related injury, would make the treatment and comparison groups less equivalent. In this case, these applicants would not have been excluded from the comparison arm of our study, although statistical methods to account for such differences were applied. Veterans and caregivers not approved for the program were provided standard VA benefits, including case management, and/or home and community-based services if clinically eligible, as well as the standard VA family caregiver services and supports described above.

The analytical sample was subject to additional exclusion criteria. Veterans were excluded from the treatment group if their caregiver was enrolled in the program for fewer than 90 consecutive days (because of disenrollment or possibly death), and from the study if their identification number could not be matched to VA data, were over the age of 65 years as of 9/1/2001, had a home zip code outside of the US or Puerto Rico at the time of application (veterans with a Puerto Rico zip code were included), or had a missing Nosos score. The Nosos score is a comorbidity index developed for VA-users (Online Appendix A) (Wagner et al. 2016). Our exclusion criteria were designed to ensure that the comparison group resembled the treatment group. Therefore, we also excluded from the comparison group individuals who at the time of application were older than 68, the oldest age of anyone who applied and was approved for PCAFC participation. For greater detail about inclusion/ exclusion criteria, please see (Van Houtven et al. 2017). The treatment group comprised veterans whose caregiver applied to and was approved for participation in the PCAFC. Median time between application and approval date was 54 days. The comparison group was comprised of veterans whose caregiver applied to the PCAFC during the same timeframe, but was determined to be ineligible. This comparison group was chosen because veterans had a caregiver that self-identified as needing support.

Data

VA electronic health record data for use of VA and VA-purchased care between May 1, 2010 and September 30, 2014 was obtained from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy & Planning (ADUSH), and the Vital Status Mini file. Data about application date, program eligibility determination, and caregiver relationship to the veteran were obtained from the Caregiver Application Tracker (CAT).

Variables

Three outpatient access to care outcomes were examined: (1) any VA-provided or VA-purchased outpatient mental health service use; defined by an algorithm using mental health diagnosis codes and/or clinic stop codes (designation used by VA to identify workload) (McCarthy and Blow 2004); (2) any VA-provided specialty care; defined by a medical specialty clinic stop codes (e.g., allergy immunology, dermatology, diabetes, cardiology, nephrology, hepatology, etc.); (3) any VA-provided primary care; defined using VA primary care clinic stop codes. Specialty care did not include visits to primary care, mental health clinics, respite care, adult day health, or institutional care. VA-purchased care is care paid for by VA and provided in the community by non-VA providers; VA-purchased care was only defined for mental health care because those services were identified using a mental health diagnosis code whereas primary and specialty care were identified by VA-specific clinic stop codes pertaining only to VA-provided care.

Each service outcome described above was measured as a binary indicator of service use during each of eight 6-month intervals; application date was the index date for each participant. Two 6-month periods occurred prior to application date so that we could compare pre-post application date trends. Service use for veterans who died during a specific interval was included in the analysis, but the veteran was subsequently censored. Death rates were low (< 1%) and were similar in the treatment and comparison groups. Application dates differed among caregivers; therefore, the number of post-application intervals varied by veteran and ranged from one to six. Due to varying application dates, fewer veterans had the full 36-month follow-up compared with veterans who had at least 12 months of follow-up, but all veterans had at least one 6-month follow-up interval (Online Appendix B). Other than a small number of deaths, there was no loss to follow up. Veterans not receiving any VA or VA-purchased care were considered to have received no care.

Treatment was defined as the veteran’s caregiver having ever been accepted into the PCAFC. The moderating variable, PTSD diagnosis, was defined by the presence of an ICD-9 code (309.81) in VA medical files in the year prior to and including the application date.

Propensity Score Weighting

This analysis relied on observational data in which caregivers of veterans were not randomized to receive PCAFC support, therefore, baseline differences in veteran characteristics between program participants and non-participants were observed. To address observed baseline differences between participants and non-participants, propensity score weights were applied to the analytic models (Austin and Stuart 2015; Rubin 1974, 2010). We constructed the propensity score weights to balance characteristics between veterans who were accepted and those not accepted into the PCAFC; specifically, variables used to construct propensity score weights were chosen to account for observable factors that influenced eligibility and service use outcomes, such as veteran need, prior health service use, caregiver/veteran relationship, demographic characteristics, and institutional factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Unweighted sample characteristics

| Veteran characteristics | Unweighted characteristics (trimmed sample) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | No PTSD | |||||||||

| Treatment (n = ll,510) |

Comparison (n = 4941) |

Standardized differencesa |

Treatment (n = 4144) |

Comparison (n = 3685) |

Standardized differencesa |

|||||

| Age at application date, mean (standard deviation SD) | 36.13 | 8.70 | 37.60 | 9.94 | −16.14 | 36.53 | 9.54 | 40.95 | 11.16 | −42.76 |

| Caregiver is a veteran, proportion | 0.12 | 0.10 | 3.50 | 0.12 | 0.13 | −1.85 | ||||

| Male, proportion | 0.93 | 0.91 | 9.60 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 10.67 | ||||

| Housing instability in past 12 months, proportionb | 0.07 | 0.09 | −6.84 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.14 | ||||

| Veteran race, proportion | ||||||||||

| White | 0.71 | 0.63 | 16.14 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 31.29 | ||||

| Black | 0.17 | 0.25 | −21.19 | 0.22 | 0.37 | −32.22 | ||||

| Other | 0.07 | 0.06 | 2.72 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 5.81 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −8.21 | ||||

| Ethnicity, proportion | ||||||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.14 | 0.10 | 11.35 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 11.34 | ||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 0.83 | 0.87 | −10.54 | 0.83 | 0.85 | −6.04 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −6.11 | ||||

| Veteran insurance status, proportion | ||||||||||

| Non-VA insurance coveragec | 0.15 | 0.11 | 12.11 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 17.92 | ||||

| Means test status, proportion | ||||||||||

| Copay required | 0.11 | 0.11 | −2.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.77 | ||||

| Copay not required | 0.72 | 0.71 | 3.78 | 0.60 | 0.57 | 7.82 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.17 | 0.18 | −2.74 | 0.26 | 0.30 | −9.17 | ||||

| Enrollment priority group, proportion | ||||||||||

| Group 1 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 12.91 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 8.31 | ||||

| Group 2–4 | 0.08 | 0.09 | −5.66 | 0.13 | 0.15 | −5.85 | ||||

| Group 5–8 or missing | 0.04 | 0.11 | −12.86 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −4.99 | ||||

| Service connectedd | ||||||||||

| High (≥70%) | 0.75 | 0.68 | 16.21 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 15.61 | ||||

| Medium high (50–69%) | 0.12 | 0.15 | −7.75 | 0.10 | 0.15 | −13.09 | ||||

| Medium low (10–49%) | 0.07 | 0.09 | −8.78 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1.22 | ||||

| Low (< 10%) | 0.07 | 0.19 | −8.78 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 1.22 | ||||

| Caregiver’s relationship to veteran, proportion | ||||||||||

| Spouse/partner | 0.83 | 0.78 | 15.88 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 1.49 | ||||

| Mother or father | 0.08 | 0.08 | −2.09 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 18.37 | ||||

| Other non-relative/not available | 0.04 | 0.08 | −17.89 | 0.04 | 0.08 | −15.09 | ||||

| Other relative | 0.05 | 0.07 | −6.79 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −10.12 | ||||

| Marital status, proportion | ||||||||||

| Married | 0.70 | 0.66 | 8.45 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.00 | ||||

| Divorced/separated | 0.12 | 0.14 | −7.43 | 0.10 | 0.12 | −4.60 | ||||

| Never married/single/widowed | 0.17 | 0.19 | −3.45 | 0.20 | 0.14 | 14.33 | ||||

| Unknown | 0.01 | 0.05 | −1.54 | 0.01 | 0.09 | −15.89 | ||||

| Physical health diagnoses, proportion | ||||||||||

| Diabetes | 0.08 | 0.10 | −6.68 | 0.08 | 0.13 | −14.21 | ||||

| Hearing: loss, pain, other | 0.21 | 0.18 | 8.83 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 3.43 | ||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.30 | 0.30 | −0.12 | 0.22 | 0.26 | −7.50 | ||||

| Hypertension | 0.26 | 0.27 | −3.47 | 0.21 | 0.27 | −13.22 | ||||

| Obesity | 0.21 | 0.20 | 2.06 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 1.18 | ||||

| Pain, not including back or joint | 0.53 | 0.47 | 10.98 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 11.35 | ||||

| Neoplasm | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1.10 | 0.07 | 0.09 | −7.64 | ||||

| Headache | 0.23 | 0.19 | 10.77 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 6.33 | ||||

| Joint pain, not including back | 0.45 | 0.42 | 4.89 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 2.09 | ||||

| Musculoskeletal disorder | 0.71 | 0.68 | 6.64 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 4.76 | ||||

| Traumatic brain injury (TBI) | 0.38 | 0.28 | 22.62 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 32.45 | ||||

| Chest pain/acute myocardial infarction | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.41 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −3.62 | ||||

| Mental health diagnoses, proportion | ||||||||||

| Adjustment reaction | 0.10 | 0.11 | −3.42 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 9.58 | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.28 | 0.29 | −1.31 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 7.76 | ||||

| Bipolar | 0.12 | 0.11 | 1.80 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 7.38 | ||||

| Depression | 0.60 | 0.59 | 1.78 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 11.18 | ||||

| Other mental healthe | 0.19 | 0.17 | 5.38 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 10.00 | ||||

| Tobacco use | 0.26 | 0.25 | 2.46 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 5.21 | ||||

| Alcohol or substance abuse disorder | 0.26 | 0.27 | −4.12 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 1.68 | ||||

| Nosos score, mean (SD)f | 1.44 | 1.63 | 1.35 | 2.55 | 5.20 | 1.48 | 1.70 | 1.01 | 1.61 | 21.36 |

| Number of VA primary care clinic stops in 6 months | 1.71 | 1.76 | 1.55 | 1.67 | 9.09 | 1.17 | 1.63 | 1.05 | 1.51 | 7.45 |

| prior to application, mean (SD) | ||||||||||

| Number of mental health visits in 6 months prior to | 6.58 | 9.82 | 5.83 | 9.38 | 7.65 | 2.41 | 7.00 | 1.62 | 5.78 | 11.71 |

| application, mean (SD) | ||||||||||

| FY2011 facility complexity level, proportiong | ||||||||||

| Facility complexity level la | 0.37 | 0.38 | − 1.99 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 2.60 | ||||

| Facility complexity level lb | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.89 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 2.01 | ||||

| Facility complexity level lc | 0.20 | 0.23 | −7.54 | 0.18 | 0.21 | −7.81 | ||||

| Facility complexity level 2 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 1.71 | 0.19 | 0.20 | −1.83 | ||||

| Facility complexity level 3 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 9.05 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 6.11 | ||||

| Miles from nearest VA Medical Center, mean (SD)h | 39.17 | 35.41 | 40.61 | 35.31 | −4.15 | 37.91 | 33.23 | 38.94 | 32.37 | −3.02 |

| VISN (Veteran Integrated Service Network) of closest VA Medical Center, proportionh | ||||||||||

| Upstate New York | 0.02 | 0.02 | 3.74 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 6.02 | ||||

| New England | 0.03 | 0.02 | 6.76 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 9.04 | ||||

| Midwest | 0.02 | 0.01 | 7.27 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 10.02 | ||||

| Desert Pacific | 0.07 | 0.04 | 11.97 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 11.65 | ||||

| Sierra Pacific | 0.05 | 0.03 | 11.17 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 10.58 | ||||

| Northwest | 0.07 | 0.05 | 6.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 7.27 | ||||

| Rocky Mountain | 0.04 | 0.07 | −14.67 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −7.28 | ||||

| Southwest | 0.07 | 0.04 | 12.30 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 7.57 | ||||

| Heart of Texas | 0.06 | 0.12 | −19.61 | 0.07 | 0.12 | −17.02 | ||||

| South Central | 0.04 | 0.10 | −25.42 | 0.05 | 0.09 | −17.18 | ||||

| Heartland | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.50 | ||||

| Great Lakes | 0.03 | 0.02 | 5.61 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 9.39 | ||||

| Veterans in partnership | 0.04 | 0.03 | 2.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 4.23 | ||||

| Ohio | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.52 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.79 | ||||

| Mid-South | 0.07 | 0.06 | 5.61 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 6.31 | ||||

| Sunshine | 0.09 | 0.08 | 3.62 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 5.79 | ||||

| Southeast | 0.07 | 0.14 | −26.34 | 0.08 | 0.20 | −33.86 | ||||

| Mid-Atlantic | 0.08 | 0.08 | 3.45 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 4.18 | ||||

| Capitol | 0.02 | 0.01 | 5.09 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 8.92 | ||||

| Stars and stripes | 0.04 | 0.02 | 9.76 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 11.05 | ||||

| New York/New Jersey | 0.03 | 0.01 | 13.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 11.30 | ||||

The standardized difference for continuous variables is calculated as, where T refers to the treatment group and C refers to the comparison group For discrete variables, where PT and Pc refer to the proportion of the treatment group and the proportion of the comparison group, respectively, having a given characteristic

Assessed in the year prior to and including application date

Veterans may have more than one type of insurance

Low category includes veterans with no service connection record or with a record found but had missing data for service connection status; veterans who are not service connected; and veterans who are service connected but have missing data for service connection percentage

Other mental health includes a large number of diagnoses

If available, the Nosos score from the fiscal year prior to Application Date fiscal year was used. If not available, the current fiscal year Nosos data was used. If neither the year prior nor the current fiscal year Nosos data was not available, Nosos data from prior years was used. Nosos scores are new measures of medical complexity derived from existing risk scores plus additional factors used in a regression model to model annual VA costs per patient

Facilities are categorized according to complexity level which is determined on the basis of the characteristics of the patient population, clinical services offered, educational and research missions and administrative complexity. Facilities are classified into three levels with Level 1 representing the most complex facilities, Level 2 moderately complex facilities, and Level 3 the least complex facilities. Level 1 is further subdivided into categories 1a–1c. Reference: http://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/2012_VHA_Facility_Quality_and_Safety_Report_FINAL508.pdf

Closest VAMC or Independent Outpatient Clinic at time of application, based upon distance from veteran’s zip code

Propensity scores were estimated within PTSD diagnosis strata (Green and Stuart 2014) (Online Appendix A). Individuals in the comparison group were assigned weights based on how representative their characteristics were of individuals in the treatment group to enhance observed comparability across the two groups. The purpose of this evaluation was to assess the effect of the PCAFC on those enrolled, therefore the average treatment effect among the treated (ATT) was of primary interest. To estimate the ATT, individuals in the treatment group were assigned a weight of 1 and individuals in the comparison group were assigned a weight of (propensity score)/(1 - propensity score). To assess overlap on observed baseline covariates, graphical depictions of the propensity score distribution and standardized differences stratified by treatment group and PTSD diagnosis were examined (Online Appendix C). To further improve balance, individuals whose propensity scores did not overlap with scores observed in the other treatment group were trimmed from the sample (Austin 2009). Thus, individuals in the PTSD diagnosis group who had a propensity score > 0.95 or < 0.25 and individuals in the no PTSD diagnosis group with a propensity score > 0.95 or < 0.10 were excluded from the sample [total trimmed n = 662 (3%); comparison n = 480 (5%); treated n = 182 (1%)]. Propensity score trim thresholds differ by PTSD status because the propensity score model was estimated within PTSD diagnosis strata. The final analytical sample included 15,654 veterans in the treatment group (n = 11,510 with PTSD; n = 4144 without PTSD) and 8626 veterans in the comparison group (n = 4941 with PTSD; n = 3685 without PTSD) (Online Appendix D).

Analytic Strategy

Generalized linear models were fit using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with a logit link, binomial variance structure, and empirical sandwich standard errors. At the suggestion of the reviewer, we also fit log binomial models (Spiegelman and Hertzmark 2005; Williamson et al. 2013) (i.e., binomial variance structure with a log link) using GEEs with the otherwise same specification as described below to produce risk ratios. Logistic regression models are a standard analytic approach to binary outcome data and are consistent with the analyses presented in related papers (Van Houtven et al. 2017), and thus we report the results from the logistic regression models. The results of the log binomial models produced slightly different results and are available from the authors.

Service use outcome models included a term for treatment, PTSD diagnosis, time dummy coded for each 6-month interval and all possible two- and three-way interaction terms. Models were weighted by the propensity score weights, defined above, to estimate both (1) differences in probability of receiving outpatient services at baseline and over time by PTSD status for veterans enrolled and not enrolled in PCAFC and (2) the effect of treatment on the probability of receiving outpatient services for veterans with and without a PTSD diagnosis. To test the hypotheses of research questions 1 and 2 stated in the Introduction, four joint score tests were conducted for each service use outcome (i.e. score tests for PTSD effect within each treatment arm and score tests for treatment effect within PTSD subgroup). Joint score tests for PTSD effect within each treatment arm (research question 1) and treatment effect within PTSD subgroups (research question 2) included two-way interactions between all six post-application time periods and treatment or PTSD status.

These models were also used to estimate whether base-line PTSD diagnosis moderated the association between program participation and service use outcomes (research question 3). To test the hypothesis of question 3 that there was a difference in program effect between individuals with and without a baseline PTSD diagnosis over time on the odds of each outpatient service use outcome, a joint score test of the sum of the PTSD and PCAFC interaction and each three-way interaction term incorporating the effect of PTSD, treatment, and post-application time period was conducted. As a sensitivity analysis suggested by the reviewer, we also conducted joint score tests consisting solely of each three-way interaction term incorporating the effect of PTSD, treatment, and post-application time period. This is equivalent to testing whether baseline PTSD diagnosis moderated the association in a difference- in-difference analysis, comparing the difference within each treatment-PTSD status group between the proportion incurring service use at each follow-up time point with the proportion incurring in the first 6-month time interval prior to application and assessing whether this difference-in-difference differed by baseline PTSD diagnosis. A statistically significant Chi Square statistic would suggest that PTSD diagnosis modified the association in at least one time point while controlling for an inflated type 1 error rate by simultaneously testing multiple time points.

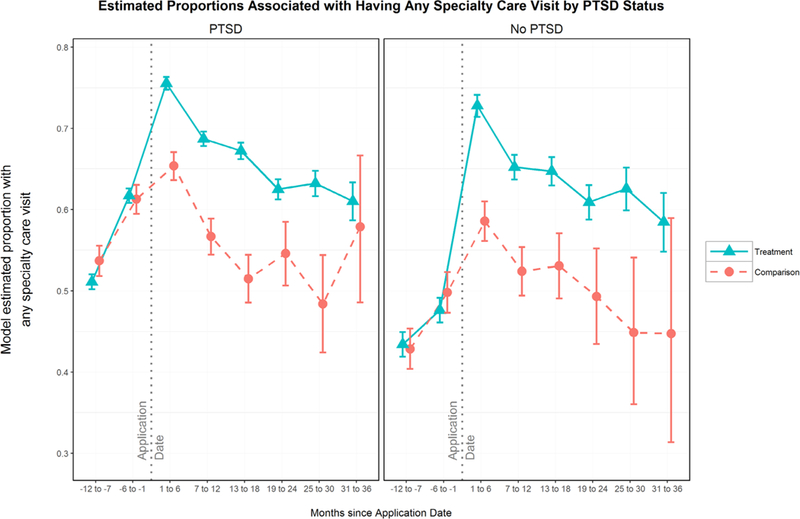

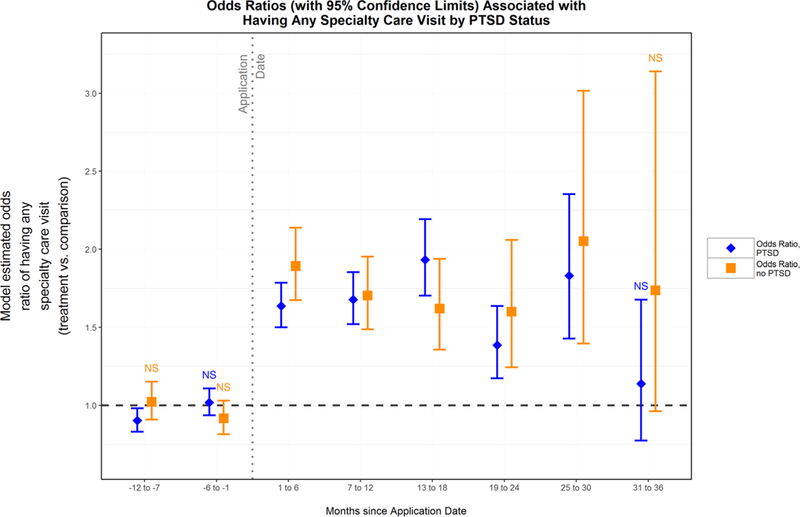

Trends in access to care are presented in graphical form and represent the weighted model-estimated proportions and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the three types of service outcomes by treatment condition and PTSD diagnosis over time. The modeled associations between program participation and any of each type of outpatient service use are represented by odds ratios (OR) and associated 95% CIs. To improve comparability of health service use by treatment group, the graphs display model-estimated proportions and ORs by PTSD-subgroup.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis where the small number of individuals who died during the follow up period were removed from the analytical models. Statistical significance levels set at 0.05; SAS 9.4 and SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 were used (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). This work was a quality improvement project for VA operational partners in the VA Caregiver Support Program and was not subject to VA Internal Review Board review.

Results

Descriptive

At baseline prior to weighting, veterans in the PCAFC were slightly younger, used more health services, had higher levels of service connection, and had more pain- and mental health-related diagnoses. Further, a higher proportion of veterans in PCAFC were White, Hispanic, and male (Table 1). PTSD diagnosis was more prevalent among veterans enrolled in the PCAFC (74% in treatment group, 57% of comparison group). The vast majority (98%) of veterans with a PTSD diagnosis had at least one additional physical or mental health comorbidity. Rates of any mental health service use at baseline were highest among veterans with PTSD. See Online Appendix E for number of outcome events at each time point.

Most variables achieved greater overlap across treatment group after propensity score weights were applied; all weighted standardized differences were well below ten (Online Appendix A, Table 2a), and weighted pre-application trends (12–1 months prior to application date) in service use between treated and comparisons were not statistically different across PTSD strata.

Outcome Models

Mental Health Service Use

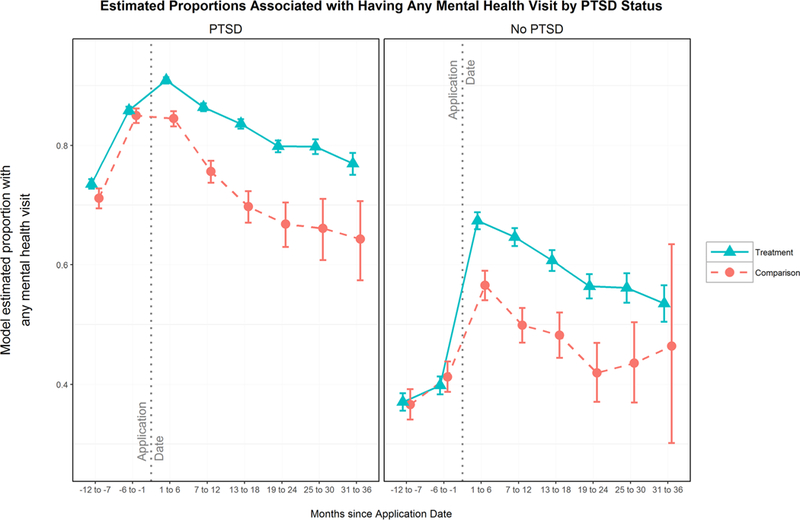

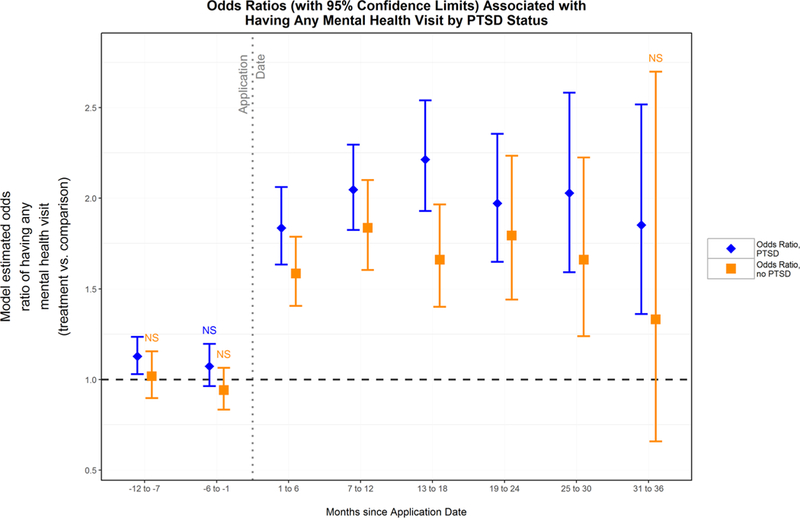

Regardless of treatment condition, a higher proportion of veterans with a PTSD diagnosis used any mental health services during at-least one time point than veterans without a PTSD diagnosis (Table 2; Fig. 1). Among veterans with PTSD and without PTSD, those in the treatment group were more likely to use any mental health services than those in the comparison group (Table 1; Fig. 2). However, the association between participation in the PCAFC and any mental health service use was not moderated by PTSD diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Joint score Chi Square, test statistics and p values from logistic regression analytical models

| Treatment vs. com parison by PTSD diagnosisa |

PTSD vs. no PTSD by treatment conditiona |

Treatment vs. com parison moderated by PTSDa |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | No-PTSD | Treatment | Comparison | - | |

| Mental health service use | 198.47** | 105.48** | 1017.75** | 416.69** | 8.68 |

| Primary care service use | 254.60** | 165.10** | 107.43** | 29.88** | 13.55* |

| Specialty care service use | 232.88** | 141.52** | 22.33* | 26.58** | 9.65 |

Degrees of freedom for all joint tests = 6

Denotes statistical significance at p < 0.05

Denotes statistical significance at p < 0.001

Tested all timepoints after baseline

Fig. 1.

Estimated proportions associated with having any mental health visit by PTSD status. Figures 1, 3, and 5 represent the model-estimated proportion in each group (treatment and comparison) by PTSD diagnosis receiving any of the specified type of care at each 6-month interval, with 95% confidence intervals at each time point

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios (with 95% confidence limits) associated with having any mental health visits by PTSD status. Figures 2, 4 and 6 represent the model-estimated odds ratios, comparing the odds of someone in the treatment group receiving that type of care compared to a similar individual in the comparison group. An odds ratio of 1.0 indicates no difference between groups. 95% confidence intervals are provided at each time point, and periods without statistically significant differences are denoted with ‘NS’

Primary Care Service Use

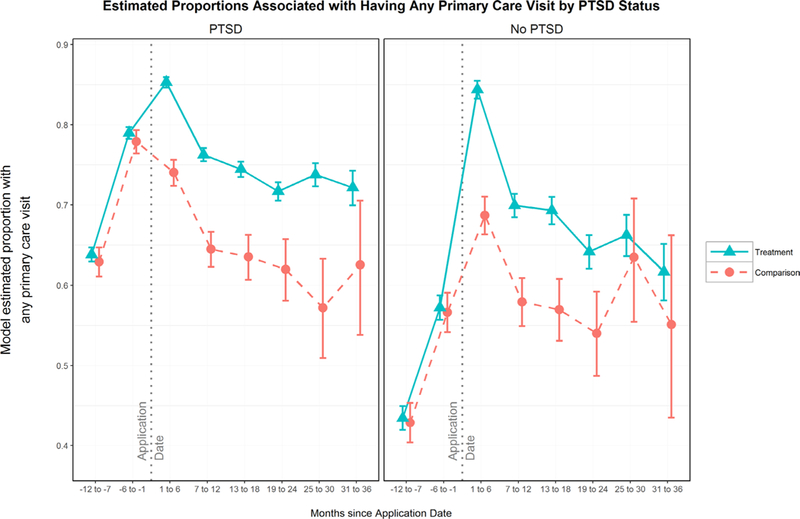

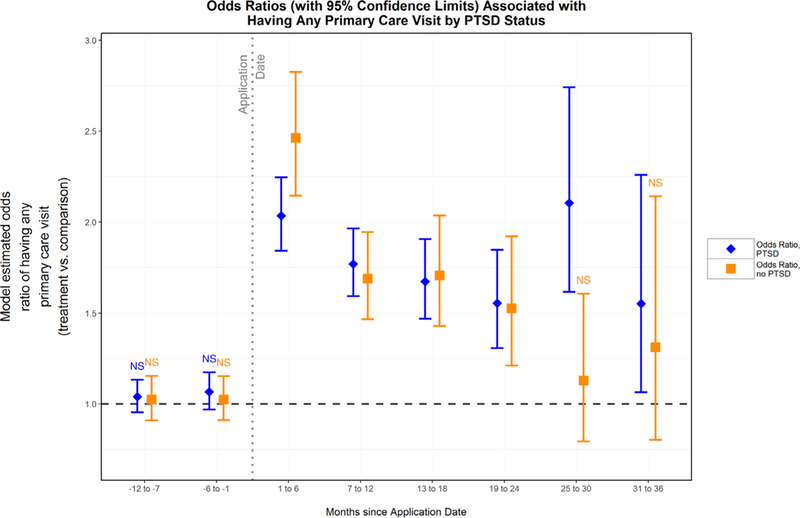

Regardless of treatment condition, veterans with PTSD had a higher likelihood of any primary care service use (Table 2; Fig. 3). Among veterans with PTSD and without PTSD, those in the treatment group were more likely to use any primary care compared with veterans in the comparison group (Table 2; Fig. 4). Further, PTSD diagnosis did moderate the association between participation in PCAFC and any primary care use (Table 2); this result was confirmed in the difference-in-difference sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 3.

Estimated proportions associated with having any primary care visit by PTSD status

Fig. 4.

Odds ratios (with 95% confidence limits) associated with having any primary care visits by PTSD status

Specialty Service Use

Independent of treatment condition, veterans with PTSD had a statistically significant higher probability of any specialty care use over time (Table 2; Fig. 5). Among veterans with PTSD and without PTSD, those in the treatment group were more likely to use any specialty care after baseline compared with veterans in the comparison group (Table 2; Fig. 6). However, the association between program participation and any specialty service use was not moderated by PTSD diagnosis when testing all time points jointly (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Estimated proportions associated with having any specialty care visit by PTSD status

Fig. 6.

Odds ratios (with 95% confidence limits) associated with having specialty care visits by PTSD status

Sensitivity Analysis

Results from the sensitivity analysis without the individuals who died during follow up were nearly identical to results from the main models.

Discussion

This study examined the associations between PTSD diagnosis and the odds of outpatient service use, PCAFC participation and the odds of outpatient service use, and whether PTSD diagnosis moderated the association between PCAFC participation and the odds of outpatient service use. Results indicate that veterans with PTSD may have a higher like-lihood of accessing services compared to veterans with-out PTSD, which is consistent with prior work (Calhoun et al. 2002). This is important considering that veterans with a PTSD diagnosis may have a greater need for mental and physical health care compared to veterans without PTSD (Crawford et al. 2015; Elbogen et al. 2013; Frayne et al. 2011; Schnurr and Green 2004; Tanielian and Jaycox 2008). Participation in PCAFC was also associated with an increased use of any outpatient mental health, primary care, and specialty care for veterans with PTSD. Hence, these findings suggest that engaging family members in VA through multiple means, including education, interaction with VA Caregiver Support Coordinators, etc. may be an important mechanism by which to address barriers to treatment initiation and possibly adherence problems observed among post 9/11 service era veterans (Crawford et al. 2015; Elbogen et al. 2013).

However, this study did not identify a differential effect of PCAFC participation on access to outpatient services among veterans with PTSD, except for primary care. First, it is possible that there was no differential unmet need for mental and specialty health services between veterans with and without PTSD. We assumed that veterans with PTSD would have higher unmet health care needs than veterans without PTSD because PTSD symptoms are related to poor treatment-seeking behaviors (Hundt et al. 2014; Ouimette et al. 2011; Spoont et al. 2014). However, within the Department of Defense (DoD) and VA there exist multiple opportunities for individuals with PTSD to be screened and ushered into VA services, increasing the likelihood that veterans with PTSD are already engaged in these services. Second, PCAFC participation was related to higher use of any primary care services for veterans with PTSD. While veterans with PTSD in this sample more frequently accessed health care services than veterans without, it is possible that veterans with PTSD have a higher medical burden (Frayne et al. 2011; Hoge et al. 2007; Possemato et al. 2010) and may have a greater unmet need for primary care services that is addressed through family engagement in PCAFC. If this is the case, it is possible that referrals through program-related eligibility visits and/or increased PCAFC caregiver knowledge about primary care services may have increased access to primary care more for veterans with PTSD who do not seek a sufficient number of services to meet their medical needs.

Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations must be considered. First, as the comparison group was defined by their exclusion from PCAFC, we assume that the comparison and treatment groups are systematically different. Second, it is possible that the propensity score method did not address unobserved confounding associated with this non-equivalent comparison group. Potential unmeasured confounders may have included education, income, employment status, and caregiver health. While our team considered other methodologies to address unobserved confounding, such as instrumental variable estimation, with concerns about identifying a valid instrument, propensity score methods were determined to be the most practical approach. The balance (between PCAFC and non- PCAFC veterans and by PTSD strata) in service use trends prior to application suggests that unobserved differences were likely not present at baseline, reducing concerns that unobserved differences were associated with the outcomes (Brooks and Ohsfeldt 2013). Also, our dataset is extremely rich and we used over 70 variables to construct the propensity score. Third, due to varying application dates, few individuals contributed 3 years of post-application data and this may have hindered the ability to detect significant moderation effects in later time periods (Online Appendix E). Fourth, PCAFC provides quarterly program visits/contacts to all PCAFC participants, yet there is not a specific clinic stop code to designate these program-related visits/contacts. While subsequent work will entail exploring avenues to better identify program-related visits, through close collaboration with operational partners, we identified and systematically excluded visits that corresponded to the codes most commonly used to designate initial eligibility and quarterly visits, specifically home-based primary care. Nevertheless, study outcomes might still include some program-driven care, thus overstating the observed association between PCAFC participation and service use. Fifth, as we used electronic health record data, we were unable to assess whether increased access resulted in high value and needed care, improved health outcomes, and improved veteran and caregiver-reported outcomes, such as satisfaction, quality of life and wellbeing. Another paper is forthcoming that uses survey data to assess the relationship between PCAFC participation and caregiver-reported satisfaction with care and depressive symptoms. Finally, we were unable to examine the underlying mechanisms linking program participation and access; therefore, future research is needed to examine the effect of PCAFC participation on health and recovery outcomes and to understand the underlying mechanisms that link family member support with increased service use for veterans with PTSD. However, this analysis uses rigorous comparative effectiveness methods to address an important gap in the evidence about how support for family members might increase health service use for individuals with PTSD.

Conclusions

Consistent with goals outlined in VA’s Blueprint for Excellence (Veterans Health Administration 2014) to increase innovative patient-centered care, VA committed an exceptional amount of resources to support family caregivers as they aid the recovery and reintegration of post-9/11 veterans. This study is the first to explore the impact of VA support for caregivers on health service use among veterans with PTSD. For many veterans with a PTSD diagnosis, informed and supportive family members could be a key resource to promote recovery. In fact, the results of this study indicate that while PCAFC may not increase access more for veterans with PTSD relative to veterans without PTSD for some services, veterans with PTSD experience increased use of health care as a result of PCAFC services for family members. However, more evidence is needed to understand how policies that support family members of individuals with mental illness outside of the VA could be targeted to maximize positive health and recovery outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project is funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Caregiver Support Program, and Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (PEC 14–272) and also received support from the Center of Innovation in Health Services Research in Primary Care (CIN 13–410). Megan Shepherd-Banigan is supported by a VA OAA HSR&D PhD Fellowship TPP 21–000. Dr. Maciejewski reported ownership of Amgen stock due to his spouse’s employment. He has also received funding from the Department of Veteran Affairs HSR&D (CRE 12–306) to test methods for doing heterogeneity treatment effects analysis in three VA trials. The authors have no additional conflicts of interest to disclose. The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors gratefully acknowledge the programming assistance of Merritt Schnell and contributions of Drs. Eugene Oddone and Maren Olsen.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488–017-0844–8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

The term “family caregiver” is used by the PCAFC to designate a veteran-identified family member or friend who supports him/her because he/she is unable to perform activities of daily living or needs supervision and protection due to the residual effects of his/her war-related injuries.

References

- Alliance for the Betterment of Citizens with Disabilities. (2016). Supporting family caregiving via the federal waiver. Retrieved from http://www.abcdnj.org/publications/community-based-services/supporting-family-caregiving-via-the-federal-waiver.

- Austin PC (2009). Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in Medicine, 28(25), 3083–3107. 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC, & Stuart EA (2015). Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statistics in Medicine. https://doiorg/10.1002/sim.6607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JM, & Ohsfeldt RL (2013). Squeezing the balloon: Propensity scores and unmeasured covariate balance. Health Services Research, 48(4), 1487–1507. https://doiorg/10.1111/1475-6773.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun PS, Bosworth HB, Grambow SC, Dudley TK, & Beckham JC (2002). Medical service utilization by veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(12), 2081–2086. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford EF, Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Kudler H, Calhoun PS, Brancu M, & Straits-Troster KA (2015). Surveying treatment preferences in U.S. Iraq-Afghanistan Veterans with PTSD symptoms: A step toward veteran-centered care. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 118–126. 10.1002/jts.21993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, Kinneer P, Kang H, Vasterling JJ, … Beckham JC (2013). Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random-sample survey. Psychiatric Services, 64(2), 134–141. 10.1176/appi.ps.004792011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg LF, & Newman SL (2006). Preliminary experiences of the states in implementing the National Family Caregiver Support Program: A 50-state study. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 18(3–4), 95–113. 10.1300/J031v18n03_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayne SM, Chiu VY, Iqbal S, Berg EA, Laungani KJ, Cronkite RC, … Kimerling R (2011). Medical care needs of returning veterans with PTSD: Their other burden. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(1), 33–39. 10.1007/s11606-010-1497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, & Stuart EA (2014). Examining moderation analyses in propensity score methods: Application to depression and substance use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(5), 773–783. 10.1037/a0036515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Price M, Yuen EK, & Acierno R (2013). Predictors of completion of exposure therapy in OEF/OIF veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 50(11), 1107–1113. 10.1002/da.22207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI,& Koffman RL (2008). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. U.S. Army Medical Department Journal, 7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, Messer SC, & Engel CC (2007). Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visits, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(1), 150–153. 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt NE, Barrera TL, Mott JM, Mignogna J, Yu HJ, San-sgiry S, … Cully JA (2014). Predisposing, enabling, and need factors as predictors of low and high psychotherapy utilization in veterans. Psychological Services, 11(3), 281–289. 10.1037/a0036907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin BE, Ruzek JI, Chard KM, Eftekhari A, Monson CM, Hembree EA, … Foa EB (2010). Dissemination of evidence- based psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(6), 663–673. 10.1002/jts.20588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JF, & Blow FC (2004). Older patients with serious mental illness: Sensitivity to distance barriers for outpatient care. Medical Care, 42(11), 1073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KM, Kabat M, Henius J, & Van Houtven CH (2015). Engaging, supporting, and sustaining the invisible partners in care: Young caregivers of veterans from the post-9/11 era. North Carolina Medical Journal, 76(5), 320–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Vogt D, Wade M, Tirone V, Greenbaum MA, Kimerling R, … Rosen CS (2011). Perceived barriers to care among veterans health administration patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services, 8(3), 212–223. 10.1037/a0024360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Possemato K, Wade M, Andersen J, & Ouimette P (2010). The impact of PTSD, depression, and substance use disorders in disease burden and health care utilization among OEF/OIF veterans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 218–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Tanielian T, Fisher MP, Vaughan CA, Trail TE, Batka E, … Ghosh-Dastidar B (2014). Hidden heroes: America’s military caregivers. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1974). Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomzied studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (2010). Propensity score methods. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 149(1), 7–9. 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, & Green BL (2004). Understanding relationships among trauma, post-tramatic stress disorder, and health outcomes. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine, 20(1), 18–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Maguen S, Cohen B, Gima KS, Metzler TJ, Ren L, … Marmar CR (2010). VA mental health services utilization in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the first year of receiving new mental health diagnoses. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(1), 5–16. 10.1002/jts.20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd-Banigan M, McDuffie JR, Shapiro A, Brancu M, Sperber N, Mehta NN, … Williams JWJ (2017). Interventions to support caregivers or families of patients with TBI, PTSD, or polytrauma: A systematic review (09 – 001). Retrieved from https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/reports.cfm. [PubMed]

- Spiegelman D, & Hertzmark E (2005). Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. American Journal of Epidemiology, 162(3), 199–200. 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoont MR, Nelson DB, Murdoch M, Rector T, Sayer NA, Nugent S, & Westermeyer J (2014). Impact of treatment beliefs and social network encouragement on initiation of care by VA service users with PTSD. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 654–662. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian T, & Jaycox L (2008). Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org/pubs/mono-graphs/MG720.html.

- Van Houtven CH, Smith VA, Stechuchak KM, Shepherd-Banigan M, Hastings SN, Maciejewski ML, … Oddone EZ (2017). Comprehensive support for family caregivers. Medical Care Research and Review. 10.1177/1077558717697015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, & Weinberger M (2011). An organizing framework for informal caregiver interventions: Detailing caregiving activities and caregiver and care recipient outcomes to optimize evaluation efforts. BMC Geriatrics, 11, 77 10.1186/1471-2318-11-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veterans Health Administration. (2014). Blueprint for excellence. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner TH, Upadhyay A, Cowgill E, Stefos T, Moran E, Asch SM, & Almenoff P (2016). Risk adjustment tools for learning health systems: A comparison of DxCG and CMS-HCC V21. Health Services Research. 10.1111/1475-6773.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson T, Eliasziw M, & Fick GH (2013). Log-binomial models: Exploring failed convergence. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 10(1), 14 10.1186/1742-7622-10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.