Abstract

Background

Studies from different Western countries have reported a rapid increase in spinal surgery rates, an increase that exceeds by far the growing incidence rates of spinal disorders in the general population. There are few studies covering all lumbar spine surgery and no previous studies from Norway.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to investigate trends in all lumbar spine surgery in Norway over 15 years, including length of hospital stay, and rates of complications and reoperations.

Design

A longitudinal observational study over 15 years using hospital patient administrative data and sociodemographic data from the National Registry in Norway.

Setting and participants

Patients aged ≥18 years discharged from Norwegian public hospitals between 1999 and 2013.

Outcome measures

Annual rates of simple (microsurgical discectomy, decompression) and complex surgical procedures (fusion, disc prosthesis) in the lumbar spine.

Results

The rate of lumbar spine surgery increased by 54%, from 78 (95% CI (75 to 80)) to 120 (107 to 113) per 100 000, from 1999 to 2013. More men had simple surgery whereas more women had complex surgery. Among elderly people over 75 years, lumbar surgery increased by a factor of five during the 15-year period. The rates of complications were low, but increased from 0.7% in 1999 to 2.4% in 2013.

Conclusions

There was a substantial increase in lumbar spine surgery in Norway from 1999 to 2013, similar to trends in other Western world countries. The rise in lumbar surgery among elderly people represents a significant workload and challenge for health services, given our aging population.

Keywords: neurosurgery, orthopaedic and trauma surgery, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study covers all lumbar spine surgery in Norwegian public hospitals across 15 years, and all annual rates during the time period were adjusted for age and gender.

In order to minimise the risk of misclassification, surgical procedure codings were used in combination with diagnoses to group all surgery into two main categories; simple surgery such as microdiscectomy and decompression, and complex surgery such as fusion and disc prosthesis.

This study did not include data from private clinics, which currently cover ~7% of the elective surgery in Norway.

Cases for non-lumbar indications, cancer, trauma, infection, pregnancy and inflammation were excluded.

The design and material of this study did not allow us to adjust for all potential confounding factors, that might have influenced the multivariate analyses of complications due to surgery.

Introduction

Low back pain is the leading cause of years lost to disability worldwide, and this burden is increasing as our population ages.1 Low back pain was responsible for 60.1 million disability-adjusted life years in 2015, an increase of 54% since 1990, with the largest increase seen in low-/middle-income countries.1 The economic burden is extensive, mostly due to sickness absence costs, but also due to the high cost of diagnostic tests and, in particular, spinal surgery.1 The use of spinal surgery has increased considerably in many Western countries over the last 20 years.2–11 This increase cannot be explained by higher incidence or prevalence rates of spinal disorders,2–7 and there are marked variations in spinal surgery rates between and within countries.7 11

National administrative databases provide important information regarding health services, which is crucial for planning and allocating healthcare resources. Many previous studies on the rates of all types of lumbar surgery come from the USA.2 4 7 9 There are also studies from Germany,6 UK,10 Sweden3 and Denmark,5 but none from Norway. Moreover, none of the published studies provide an overview of all types of lumbar spinal surgery including simple surgical procedures such as microsurgical discectomy and/or decompression, and complex procedures such as fusions and disc prosthesis. An overview of all spinal surgery, including complication and reoperation rates, will provide important information for the evaluation of current public health services, as well as the planning of future services.

Hence, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the longitudinal trends in hospital discharges of all surgical procedures for lumbar spine disorders in Norway from 1999 to the end of 2013. Further, length of hospital stay, and rates of complications and reoperations over the 15-year period were investigated.

Material and methods

Design

This was a retrospective, longitudinal, observational study comprising all discharges from Norwegian public hospitals over a 15-year period (1999–2013). Norway (population of 4.46 million in 1999 and 5.05 million in 2013)12 has a national healthcare system divided into four health regions (South-East, West, Middle and North). Private surgery, primarily day surgery, became available after 2007. It is estimated that currently ~7% of all elective spinal surgeries take place in the private sector.13

Data source

Hospital patient administrative data were retrieved from a national database located at the Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services. The database was initially established as a part of the project ‘Post-hospitalization survival rates in Norway as indicators of hospital quality’. A detailed description of the methods employed in data collection is published elsewhere.14 Patient administrative data for the period 1999–2009 were extracted directly from all Norwegian public hospitals, and, for the period 2010–2013, from the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR). Norwegian hospitals were mandated to submit data to the NPR since 2010. Each hospitalisation record contains a personal identifier, codes for diagnoses, medical procedures, and date and time of admission and discharge. Data from the National Registry provided by Statistics Norway made it possible to link the NPR data to patients’ age, sex and municipality of residence. Each entry in the database represents a single hospitalisation record including diagnoses based on International Classification of Disease, version 10 (ICD-10) and surgical procedure codes based on the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP).15 The NOMESCO Classification has been used in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland and Estonia since 1999. The NSCP algorithm used in this study has been validated by the Norwegian registry for spine surgery (NORspine)16 and the NPR under the Norwegian Directorate of Health.17

Patient and public involvement

Due to the use of administrative data in this study patients or public were not involved in this project.

Selection of sample and classification of outcome

Inclusion criteria were age ≥18 years and a lumbar spine diagnosis code (ICD-codes from M40 to M54). Exclusion criteria were diagnoses related to the cervical, thoracic or an unspecified region of the spine, as well as diagnoses indicating cancer, trauma, spinal fractures, pregnancy, spinal infections and inflammatory diseases.

For identifying discharges with simple surgical procedures defined as discectomy and/or decompression, the following NCSP ABC codes were used15: ABC07, ABC16, ABC26, ABC28, ABC36, ABC40, ABC56, ABC66 and ABC99. The complex surgical procedures included procedure codes for fusion surgery (NAG and NAN), disc prosthesis (NAB and NAC) and revision surgery (NAT and NAU).15 Further, NAE, NAF, NAH, NAM, NAT and NAU procedure codes were included if coexisting with NCSP codes indicating a complex procedure. This is similar to the algorithm used in the NORspine16 and the NPR.17 A list of all included procedure codes can be delivered by contacting the corresponding author.

Complications were identified by the following ICD-10 codes occurring within 30 days after a discharge: postoperative haematoma (T81.0), postprocedural shock (T81.1), unintentional puncture/laceration (T81.2), disruption of wound/wound dehiscence (T81.3), infection following a procedure (T81.4), foreign body accidentally left in body following procedure (T81.5), acute reaction to foreign body accidentally left during a procedure (T81.6), vascular complications following a procedure (T81.7), unspecified or other complications of procedure, either on initial surgical admission or on readmission (T81.8–9) and complications during anaesthesia (T88.4–5). NAW (reoperation) and AW (reoperations of the nervous system) procedure codes that occurred within 30 days after the initial surgery were also classified as complications. NAW and AW procedure codes occurring later than 30 days after an initial procedure were classified as reoperations.

Background characteristics

Patient age, gender, length of hospital stay and number of operations were included. Age was categorised as 18–39, 40–59, 60–75 or >75 years.

Statistical analyses

Annual surgical incidence rates were calculated per 100 000 inhabitants based on the size of the total Norwegian population on 1 January of each analysed year, retrieved from Statistics Norway.12 Surgical incidence rates across age groups, gender and type of surgery (simple/complex) were compared with χ2-test and z-test. Length of hospital stay over the time period and in relation to background characteristics was compared using a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Possible associations between complications and background characteristics were analysed using a multivariate logistic regression. All tests were two-sided and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using SPSS V.25.0 and STATA V.MP15.

Results

A total of 67 855 discharges for 57 081 individual patients were identified. A total of 56 764 (83.7%) discharges were for simple surgical procedures and 11 091 (16.3%) discharges were for complex surgical procedures. Most of the complex surgical procedures were fusion surgeries (94.0%). Further, 48 495 individual patients (71.5%) had only one discharge due to spinal surgery. The mean age of the patients was 52.3 (SD 15.9), and 51.4% were men. Background characteristics of all included discharges are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 67 855 lumbar spine operations in 57 081 patients in Norway, 1999–2013

| No. of operations (%) | Length of stay, days, median (range, IQR) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18-39 | 16396 (24.2) | 4.2 (724, 4.4) |

| 40-59 | 28237 (41.7) | 6.3 (618, 4.7) |

| 60-75 | 16160 (23.9) | 5.9 (250, 5.8) |

| > 75 | 6910 (10.2) | 7.2 (226, 6.7) |

| Missing | 152 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 34902 (51.4) | 4.7 (239, 4.4) |

| Female | 32801 (48.3) | 6.0 (724, 5.8) |

| Missing | 152 | |

| Year of operation | ||

| 1999 | 3460 (5.1) | 7.1 (149.9, 6.0) |

| 2000 | 3996 (5.9) | 7.0 (420, 6.0) |

| 2001 | 4200 (6.2) | 7.0 (138, 6.0) |

| 2002 | 3865 (5.7) | 6.2 (202, 6.0) |

| 2003 | 4557 (6.7) | 6.1 (238, 5.4) |

| 2004 | 4396 (6.5) | 6.1 (250, 5.8) |

| 2005 | 4572 (6.7) | 6.0 (724, 5.3) |

| 2006 | 4422 (6.5) | 5.8 (138, 5.5) |

| 2007 | 4255 (6.3) | 5.1 (618, 5.0) |

| 2008 | 4164 (6.1) | 4.9 (179, 4.3) |

| 2009 | 4449 (6.6) | 4.2 (142, 4.9) |

| 2010 | 5130 (7.6) | 4.1 (183, 4.8) |

| 2011 | 5241 (7.7) | 4.0 (210, 4.2) |

| 2012 | 5597 (8.2) | 4.1 (165, 4.2) |

| 2013 | 5551 (8.2) | 3.8 (219, 4.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Simple | 56764 (83.7) | 4.3 (724, 4.3) |

| Complex | 11091 (16.3) | 8.2 (420, 5.7) |

| No. of operations | ||

| 1 | 57029 (84.0) | 5.1 (724, 5.0) |

| 2 | 8623 (12.7) | 5.2 (618, 5.1) |

| 3 | 1602 (2.4) | 6.2 (205, 6.0) |

| ≥ 4 | 467 (0.7) | 6.9 (115, 4.4) |

| Missing | 134 | 134 |

The median length of hospital stay for all patients undergoing spinal surgery decreased from 7.1 (IQR 6.0) days in 1999 to 3.8 (IQR 4.1) in 2013 (table 1). For those undergoing a complex procedure, the median length was nearly double that of those who underwent a simple procedure (8.2 (IQR 4.3) days vs 4.3 (IQR 5.7)). In the simple surgery group, the length of hospital stay was reduced from a median of 6.2 (IQR 5.0) days in 1999 to 3.1 (IQR 3.1) in 2013, and in the complex surgery group there was a reduction from a median of 11.0 (IQR 6.1) in 1999 to 7.0 (IQR 4.0) in 2013.

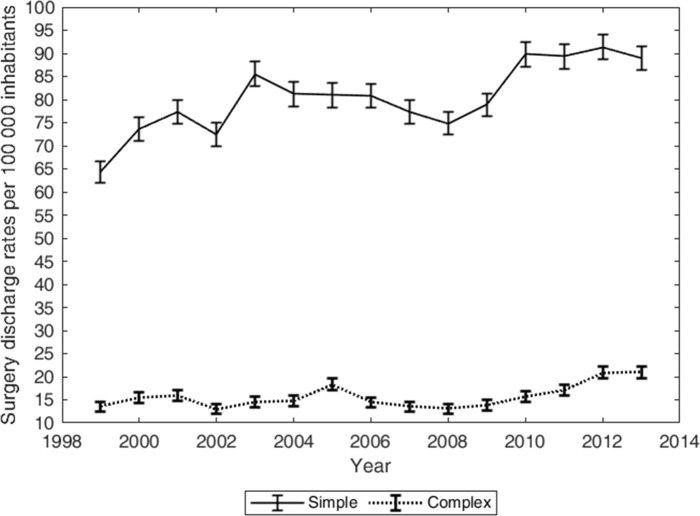

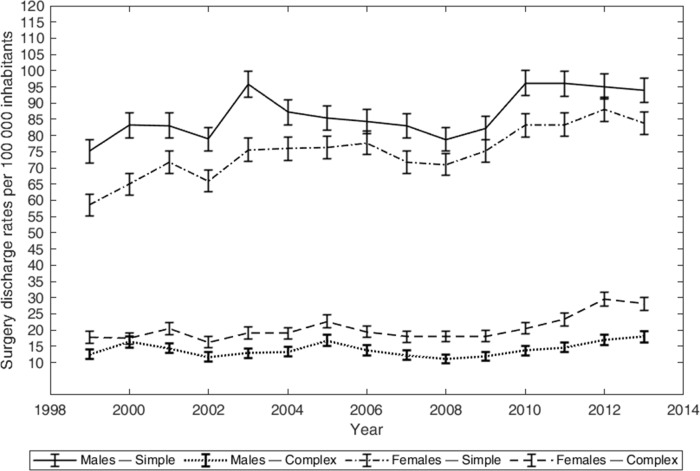

The annual surgical rate including both simple and complex procedures increased from 77.8 (95% CI (75.2 to 80.4)) per 100 000 in 1999 to 119.9 (95% CI (107.0 to 112.8)) in 2013 (figure 1). The rate of simple procedures increased by 138% (from 64.3 to 88.9 per 100 000 inhabitants for 1999 and 2013, respectively), and the rate of complex procedures increased by 154% (from 13.6 to 21.0 per 100 000). During the 15-year study period, significantly more males underwent simple surgical procedures, whereas more females underwent complex surgical procedures (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Annual surgery rates per 100 000 population of simple and complex lumbar surgical procedures in Norway from 1999 to 2013.

Figure 2.

Annual incidence per 100 000 population of simple and complex lumbar surgery in Norway from 1999 to 2013, according to sex.

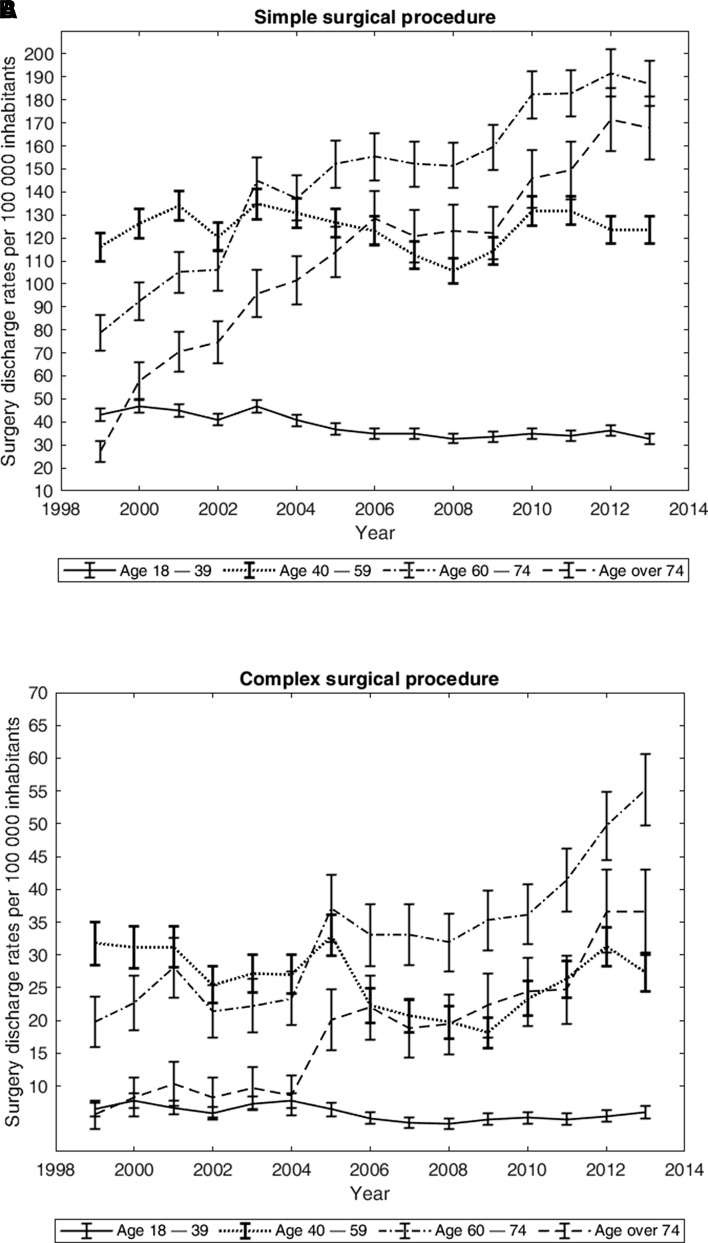

Most surgeries were performed on patients aged 40–59 years (figure 3A and B). A substantial shift towards operations performed on the older age groups is apparent for both simple and complex surgery. Among those aged 75 years and above, the rate of simple surgery increased by more than a factor of five by 2013, reaching 167.8 (154.3–181.3) (figure 3A). A similar shift was also apparent for the complex procedures (figure 3B). In 1999 only 7.8 (30.3–42.9) operated patients per 100 000 inhabitants were in the oldest age group, whereas in 2013 this rate had increased to 36.6 (30.3–42.9). In the younger age groups, the complex surgery rate remained stable over the 15-year period.

Figure 3.

Annual incidence per 100 000 inhabitants of simple and complex surgery in Norway from 1999 to 2013, according to age groups.

The occurrence of complications was generally low. During the 15-year period, a total of 977 (1.4%, 95% CI (1.38 to 1.56)) discharges were coded with diagnoses or procedures indicating complications. Of these, 42% occurred during the index stay and 68% underwent reoperation within 30 days. During the 15-year period, there was an increase in reoperations within 30 days, leading to a large increase in the complication rate, from 0.7% in 1999 to 2.4% in 2013. The multivariate analysis showed that complications were significantly associated with younger and middle-aged groups, receiving complex surgery and having an extended hospital stay (table 2). There was no statistically significant interaction between type of surgery (simple vs complex) and length of hospital stay (p=0.296), or between age groups and type of surgery (p=0.678).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression model of factors associated with complications (including reoperation within 30 days) due to lumbar spine surgery in Norway from 1999 to 2013 (n=67 855)

| Complications (n=977) |

OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18-39 | 250 | Ref | ||

| 40-59 | 460 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.13 |

| 60-75 | 198 | 0.61 | 0.50 | 0.74 |

| > 75 | 69 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.67 |

| Missing | 152 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 510 | Ref | ||

| Female | 467 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.02 |

| Missing | 152 | |||

| Length of stay (days) | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.02 | |

| Type of surgery | ||||

| Simple | 659 | Ref | ||

| Complex | 318 | 2.34 | 2.04 | 2.69 |

| Year of operation | ||||

| 1999 | 24 | Ref | ||

| 2000 | 29 | 0.98 | 0.57 | 1.71 |

| 2001 | 29 | 1.03 | 0.60 | 1.77 |

| 2002 | 33 | 1.31 | 0.77 | 2.22 |

| 2003 | 44 | 1.52 | 0.92 | 2.50 |

| 2004 | 41 | 1.46 | 0.88 | 2.43 |

| 2005 | 67 | 2.23 | 1.39 | 3.57 |

| 2006 | 60 | 2.25 | 1.40 | 3.63 |

| 2007 | 58 | 2.25 | 1.39 | 3.64 |

| 2008 | 56 | 2.29 | 1.42 | 3.71 |

| 2009 | 80 | 3.12 | 1.97 | 4.94 |

| 2010 | 89 | 3.03 | 1.93 | 4.78 |

| 2011 | 93 | 3.03 | 1.93 | 4.77 |

| 2012 | 140 | 4.31 | 2.79 | 4.67 |

| 2013 | 134 | 4.16 | 2.68 | 6.44 |

| Missing | 134 |

A total of 10 015 (14.8%, 95% CI (14.5 to 15.0))) discharges were reoperations; 517 (0.8%, 95% CI (0.8 to 0.9)) occurred between 30 and 90 days after the index discharge, 2611 (3.8%, 95% CI (3.7 to 4.0)) between 91 days and 12 months, and 2429 (3.6%, 95% CI (3.5 to 3.7)) between the first and second year. There was a large decrease in the proportion of patients who received reoperations during the 15-year period: from 21.6% in 1999 to 2.3% in 2013.

Discussion

This national study identified a significant increase in lumbar spine surgery in Norway from 1999 to 2013. This increase was most marked in the use of simple surgical procedures like microsurgical discectomy and/or decompression surgery, in particular among elderly patients above 75 years of age. The increase in complex surgery, for the most part fusion surgery, was also most prevalent in the oldest age group.

The main strength of the current study is that it covers all spinal surgery procedures carried out in public hospitals in Norway during a 15-year period, except for surgery due to red flag diagnoses (cancer, spinal infections, inflammatory diseases and so on) or trauma. A potential weakness is the risk of misclassification of diagnoses or procedures.18 The lack of accuracy of diagnosis in such registries has been reported and a systematic review on this field has showed that procedure coding might be more accurate than coding based on diagnosis.19 In order to reduce misclassification in the current study, we used the surgical procedure coding in combination with diagnoses when classifying the types of surgery provided. Further, we argue that the risk of misclassification is minor in this study as we assessed two large and different types of spinal surgery (simple vs complex spinal surgery procedures). As expected, the two groups differ with respect to length of hospital stay, complications and reoperations. We considered classifying spinal surgery into simple and complex procedures useful when reporting trends in spinal surgery within a large and heterogeneous dataset such as hospital administrative data used in this study. Finally, the present material did not include surgery conducted in private clinics/hospitals. Private for-profit hospitals in Norway perform currently ~7% of the total number of elective surgical procedures,13 usually as day surgeries. This might have contributed to the increase in complications in public hospitals after private surgery became common in 2007. Private surgery would leave the public hospitals to deal with the more complex cases and procedures during this portion of the study period (2007–2013). A previous study comparing surgery due to disc herniation in public and private hospitals in Norway, showed that patients operated by simple procedures due to lumbar disc herniation in public hospitals were older, and had more comorbidity and other risk factors associated with unfavourable outcomes compared with those operated in the private clinics.20

There are very few published papers that provide an overview of all types of spinal surgery for lumbar degenerative disorders over an extended time period. Davis21 reported that hospitalisation rates for all types of lumbar surgery (including fusion and decompression) increased markedly in the USA from 1979 to 1990. In line with Davis, our results demonstrate that more men than women received lumbar spine surgery. Several studies on the rates of different types of spinal surgery, such as disc herniation and spinal fusion surgery, have been published.2–11 22 In general, the findings in the present paper are in accordance with the other studies from Scandinavian countries3 5 and Germany,6 which show increased rates for lumbar disc herniation and spinal stenosis surgery. The increase reported in most of the western-European countries is not as large as that found in the USA2 4 7 9 11 and UK.10 Furthermore, these results also fit with the overall national healthcare expenditure across countries; in Norway it is 10.4% of the GDP, which is similar to other western-European countries such as Germany and Sweden, as compared with 17.1% in the USA.23

The increase in public lumbar spine surgery in Norway is difficult to understand, because only minor increases in the incidence and severity of low back pain have been reported in the Norwegian population.24 However, parts of the increase may be explained by the growing number of elderly patients and the increase of hospital surgeons in general.25 In addition, there has been a substantial rise in the use of radiographic examinations such as MRI, which might have led to more surgery.26 The large variations in spinal surgery rates may also be explained by a lack of uniform and consensus-based criteria for surgery, financial incentives for surgical interventions and new technology.7–10 27 There is a large need for high-quality scientific evidence as well as clinical consensus regarding an optimal use of resource-demanding investigations and treatments connected to spinal disorders. Many of the new technologies and more complex procedures have questionable clinical or cost–benefit efficacy. Furthermore, we need stronger scientific evidence with respect to the selection of patients to surgical treatment. Both in a clinical and societal perspective, non-surgical management might be an appropriate option for patients who wish to defer or avoid surgery.28 The mean complication rate during the study period was low, but it increased to 2.4% at the end of the period. This increase may be explained by the increase in reoperations within 30 days at the end of the 15-year period. Hence, there seems to be a trend towards a shorter timeframe for reoperations by the end of this 15-year time period, a trend which is also reported in the Swedish study of lumbar disc herniation surgery between 1987 and 1999.3 Our finding that older patients were less likely to experience complications and receive reoperations compared with the younger and middle-aged groups is hard to explain. It may be that surgeons are more hesitant to reoperate older people, and are more selective with respect to other potential risk factors for complications after surgery.

Concusion

There was a substantial increase in spinal surgery in Norway from 1999 to 2013. The rise in number of surgeries, in particular among elderly people, represents a significant workload for hospitals in Norway, and a challenge to the public healthcare system in terms of meeting the increased burden associated with low back pain in an ageing population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MG, JH and J-AZ designed the study. MG and MCS analysed the data. J-AZ, OF, LG, KS and TKS contributed in discussion of analyses and results presentation. MG wrote the manuscript with all authors contributing in reading, commenting and approving the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health 3 Authority, grant number 2013030.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (2014/14413) and the 8 Norwegian Regional Ethics Committee (2013/1662, REC south-east D).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin BI, Mirza SK, Spina N, et al. Trends in Lumbar Fusion Procedure Rates and Associated Hospital Costs for Degenerative Spinal Diseases in the United States, 2004 to 2015. Spine 2019;44:369–76. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jansson KA, Németh G, Granath F, et al. Surgery for herniation of a lumbar disc in Sweden between 1987 and 1999. An analysis of 27,576 operations. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rajaee SS, Bae HW, Kanim LE, et al. Spinal fusion in the United States: analysis of trends from 1998 to 2008. Spine 2012;37:67–76. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31820cccfb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rasmussen S, Jensen CM, Iversen MG, et al. [Lumbar fusion surgery for degenerative conditions in Denmark 2005-2006]. Ugeskr Laeger 2009;171:2804–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steiger HJ, Krämer M, Reulen HJ. Development of neurosurgery in Germany: comparison of data collected by polls for 1997, 2003, and 2008 among providers of neurosurgical care. World Neurosurg 2012;77:18–27. 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.05.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, et al. United States' trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992-2003. Spine 2006;31:2707–14. 10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim P, Kurokawa R, Itoki K. Technical advancements and utilization of spine surgery – international disparities in trend-dynamics between Japan, Korea, and the USA. Neurol Med Chir 2010;50:853–8. 10.2176/nmc.50.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoshihara H, Yoneoka D. National trends in the surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative disc disease: United States, 2000 to 2009. Spine J 2015;15:265–71. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sivasubramaniam V, Patel HC, Ozdemir BA, et al. Trends in hospital admissions and surgical procedures for degenerative lumbar spine disease in England: a 15-year time-series study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009011 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. An international comparison of back surgery rates. Spine 1994;19:1201–6. 10.1097/00007632-199405310-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Statistics Norway. Available: https://www.ssb.no/en/statbank 10.1371/journal.pone.0136547 [DOI]

- 13. Pedersen M, Kalseth B, Lilleeng SE, et al. Private aktører i spesialisthelsetjenesten. Omfang og utvikling 2010-2014. Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2016. Available: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/1159/Private%20akt%C3%B8rer%20i%20spesialisthelsetjenesten.%20Omfang%20og%20utvikling%202010-2014.%20IS-2450.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hassani S, Lindman AS, Kristoffersen DT, et al. 30-Day Survival Probabilities as a Quality Indicator for Norwegian Hospitals: Data Management and Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136547 10.1371/journal.pone.0136547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nordic Centre for Classifications in Health Care. NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP). Available: http://www.nordclass.se/ncsp_e.htm

- 16. Solberg T. NORspine Annual report. 2013. Available: https://www.kvalitetsregistre.no/sites/default/files/http-/www.kvalitetsregistre.no/getfile.php/Norsk/Bilder/Offentliggj-C3-B8ring-2014/-C3-rsrapport_NKR_2013-2-.pdf

- 17.https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/statistikk-registre-og-rapporter/helsedata-og-helseregistre/norsk-pasientregister-npr/innhold-og-kvalitet-i-npr/_/attachment/download/e2e96893-e676-4a56-be07-7a37589c4e83:d4503aa7adeb89ec661a9a44ee12b44cb9167add/17-9624-2%20Dekningsgrad_rapport_NKR_2015-16.pdf

- 18. Gavrielov-Yusim N, Friger M. Use of administrative medical databases in population-based research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:283–7. 10.1136/jech-2013-202744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burns EM, Rigby E, Mamidanna R, et al. Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health 2012;34:138–48. 10.1093/pubmed/fdr054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grotle M, Solberg T, Storheim K, et al. Public and private health service in Norway: a comparison of patient characteristics and surgery criteria for patients with nerve root affections due to discus herniation. Eur Spine J 2014;23:1984–91. 10.1007/s00586-014-3293-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davis H. Increasing rates of cervical and lumbar spine surgery in the United States, 1979 – 1990. Spine 1994;19:1117–22. 10.1097/00007632-199405001-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grøvle L, Fjeld OR, Haugen AJ, et al. The Rates of LSS Surgery in Norwegian Public Hospitals: A Threefold Increase From 1999 to 2013. Spine 2019;44:E372–8. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm

- 24. Kinge JM, Knudsen AK, Skirbekk V, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders in Norway: prevalence of chronicity and use of primary and specialist health care services. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:75 10.1186/s12891-015-0536-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Welle-Watne C. Utviklingen for leger og legestillinger i primær- og spesialisthelsetjenesten – Rapport 2014. Norwegian Directorate of Health, 2014. Avilable: https://helsedirektoratet.no/Lists/Publikasjoner/Attachments/957/Utviklingen-for-leger-og-legestillinger-i-prim%C3%A6r-og-spesialisthelsetjenesten-2014-IS-2252.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26. Børretzen I, Lysdahl KB, Olerud HM. Diagnostic radiology in Norway trends in examination frequency and collective effective dose. Radiat Prot Dosimetry 2007;124:339–47. 10.1093/rpd/ncm204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chou R, Baisden J, Carragee EJ, et al. Surgery for low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Spine 2009;34:1094–109. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a105fc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018;391:2368–83. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.