Abstract

Introduction

Methamphetamine misuse is classified as a ‘likely’ risk factor for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Nevertheless, the actual prevalence of and a screening strategy for PAH in methamphetamine users have not been established. We plan to study the prevalence of PAH and identify its independent risk factors among methamphetamine users.

Methods and analysis

The Screening Of Pulmonary Hypertension in Methamphetamine Abusers (SOPHMA) study will be a multicentre, cross-sectional screening study that will involve substance abuse clinics, hospitals and rehabilitation facilities in Hong Kong that cater to more than 20 methamphetamine users. A total of 400 patients who (1) are ≥18 years at enrolment; (2) report methamphetamine use in the last 2 years; (3) are diagnosed with methamphetamine use disorder; and (4) voluntarily agree to participate by providing written informed consent will be included. Patients will undergo standard echocardiography-based PAH screening procedures recommended for those with systemic sclerosis. Right heart catheterisation will be offered to participants with intermediate or high echocardiographic probability of PAH. For participants with a low echocardiographic probability of PAH, rescreening will be performed within 1 year. The primary measure will be the prevalence of PAH in methamphetamine users. The secondary measures will be the risk factors and a prediction model for PAH in methamphetamine users.

Ethics and dissemination

The SOPHMA study has been approved by the institutional review board. The findings of this study will provide the necessary evidence to establish universal guidelines for screening of PAH in methamphetamine users. Our results will be disseminated through immediate feedback to study participants, press release to the general public, as well as presentation in medical conferences and publications in peer-reviewed journals to healthcare providers and academia worldwide.

Keywords: methamphetamine, pulmonary hypertension, screening

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Screening Of Pulmonary Hypertension in Methamphetamine Abusers study will be the first to evaluate the prevalence of and identify the risk factors for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) among methamphetamine users.

This study will apply a current guideline-recommended PAH screening algorithm for systemic sclerosis to unselected methamphetamine users.

The screening strategy is an echocardiography-based protocol.

Right heart catheterisation will be confined to those with a high echocardiographic probability of PAH in accordance with guideline recommendations.

The restricted application of right heart catheterisation to those with high echocardiographic probability of PAH may underestimate the ‘true’ prevalence of PAH in methamphetamine users.

Introduction

Methamphetamine is a potent central nervous system stimulant originally prescribed for individuals with a neuropsychiatric disorder, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Due to its highly addictive nature, illicit methamphetamine use is emerging as a major public health problem worldwide. In 2013 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reported that 0.7% of the global population aged between 15 and 64 years, that is, 33.8 million individuals, reported use of methamphetamine and/or related compounds in 2010.1 This illicit methamphetamine use is expected to increase.1 In addition to the infamous methamphetamine use disorder, which is primarily a psychiatric condition due to the neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine,2 methamphetamine also affects the cardiovascular system. Chronic sympathetic activation leads to hypertension, cardiac dysrhythmias, ischaemic strokes and myocardial infarction. As methamphetamine can be inhaled in a vapourised form and smoked or snorted, serious respiratory complications can also ensue, including pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH).

PAH is a devastating and often life-threatening condition. It is haemodynamically defined as an elevated mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥25 mm Hg and elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) ≥3 Wood units combined with a normal pulmonary artery wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg in the absence of significant lung disease and/or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. The association of PAH with methamphetamine use was first described in a case report in 1993.3 In a subsequent retrospective cohort, patients with idiopathic PAH were found to have a much higher prevalence of prior use of methamphetamine and/or its related compounds (28.9%), compared with patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (4.3%) or pulmonary hypertension due to a known associated condition (3.8%).4 Although current international guidelines recognise methamphetamines as a ‘likely’ cause of drug-induced PAH,5 almost nothing is known about its prevalence and incidence among methamphetamine users.

In the REVEAL registry (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management),6 a 55-centre longitudinal USA-based PAH registry, the estimated 5-year survival from diagnosis of PAH was 49%. Since patients with PAH often remain asymptomatic in the early phase, the diagnosis is often made late in the course of the disease, when most small pulmonary arteries have been obliterated, rendering therapy ineffective.7 As such, international guidelines recommend routine screening with resting transthoracic echocardiography and biomarkers to promptly detect PAH in asymptomatic high-risk individuals such as those with systemic sclerosis.5 8 Although the prognosis of patients with methamphetamine-associated PAH appears to be much worse than for those with idiopathic PAH,9 international guidelines5 and expert consensus10 have not considered screening for PAH in asymptomatic methamphetamine users. The lack of a screening effort for PAH among methamphetamine users is due to the unknown prevalence of PAH in this population that adversely affects the cost-effectiveness of any screening procedure.8 This hampers the prospect of identifying risk factors of PAH11 and developing a prediction model for the occurrence of PAH in methamphetamine users.

The Screening Of Pulmonary Hypertension in Methamphetamine Abusers (SOPHMA) study is a cross-sectional screening study that will apply a current guideline-recommended echocardiography-based PAH screening algorithm to a large cohort of unselected methamphetamine users in Hong Kong.5 12 The study objectives include the following:

To describe the prevalence of PAH among methamphetamine users using a current guideline-recommended echocardiography-based PAH screening algorithm.

To identify independent risk factors for PAH in methamphetamine users.

To develop a prediction model for PAH in methamphetamine users.

Methods and analysis

Study design

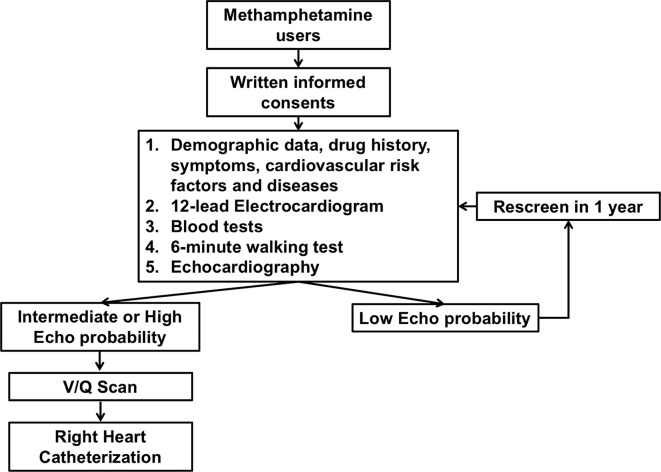

SOPHMA is a multicentre, cross-sectional screening study based in Hong Kong. Participating centres must have a specialised substance abuse service with a minimum of 20 methamphetamine users being actively followed up. The study protocol is summarised in figure 1. Box 1 summarises the five items included in the study screening procedure. According to the guidelines,5 standard right heart catheterisation will be performed on patients with intermediate or high echocardiographic probability of pulmonary hypertension. For those with a low echocardiographic probability, screening will be repeated within 1 year to ensure true negativity of the original scan.

Figure 1.

Study flow. V/Q, ventilation and perfusion.

Box 1. Screening procedure for pulmonary hypertension.

Items.

Demographic data, data pertinent to methamphetamine use and other cardiovascular risk factors/conditions.

Standard 12-lead ECG.

Plasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide and other biomarkers.

6 min walking distance.

Echocardiography.

Patients and patient recruitment strategy

Participants who fulfil the following criteria will be invited to participate in the study: (1) age ≥18 years at enrolment; (2) report of methamphetamine use in the last 2 years; (3) diagnosed with methamphetamine use disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition)13; and (4) voluntary agreement to participate by providing written informed consent. Patients who attend the substance abuse clinic with a diagnosis of methamphetamine use disorder between 1 July 2019 and 30 June 2021 and are capable of providing an informed consent will be contacted by a research nurse. The design and objectives of the study will then be explained to the patient. An invitation information leaflet detailing the study will be provided to the candidate patients at the same time. Patients who refuse to provide written informed consent will be excluded.

Demographic and serum data collection

Demographic data and a detailed history of methamphetamine use will be recorded. In addition, cardiovascular risk factors, history of other cardiovascular diseases, investigative results in the last 3 months including N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP), liver and renal function, as well as serum urate will be recorded. Table 1 summarises the demographic data and other cardiovascular risk factors and/or conditions to be collected.

Table 1.

Demographic data and data pertinent to methamphetamine use and cardiovascular diseases

| Items | |

| Demographic | Age, gender. |

| Drug history | Quantification of methamphetamine use: duration of regular use, time of first and last use, frequency of use, routes of administration, quantity consumed per day (if available). |

| Documentation and quantification of other regularly used drugs, including all self-purchased, prescribed or over-the-counter medications. | |

| Symptoms | Shortness of breath, chest pain, syncope, presyncope, dizziness, decreased exercise tolerance, bilateral lower limb swelling, New York Heart Association classification. |

| Cardiovascular risk factors and diseases | Risk factors: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, smoking, alcohol use. |

| Diseases: coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, other conduction abnormalities, prior deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism. | |

| Blood tests | Complete blood count, renal function test, liver function test, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide/Brain natriuretic peptide, high-sensitive troponin I, creatine kinase/creatine kinase-MB, urate. |

Echocardiographic examination

Detailed quantitative transthoracic echocardiography examination including two-dimensional, M-mode and Doppler flow studies will be performed in all patients. Standard two-dimensional and M-mode measurements will be performed according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography.14 Valvular regurgitation will be classified as mild, moderate or severe using a semiquantitative method.15 A standard Doppler echocardiographic method will be used to estimate cardiac output.16 For calculation of cardiac output, an average of five consecutive ventricular systoles during sinus rhythm, or an average of 13 beats in case of atrial fibrillation, will be obtained.17 Simultaneous blood pressure measurements will be recorded with a calibrated non-invasive semiautomatic device (Dinamap 1846XT; Critikon, Tampa, Florida) during the determination of cardiac output. Total vascular resistance in dyne/s/cm5 will be calculated using the following formula:

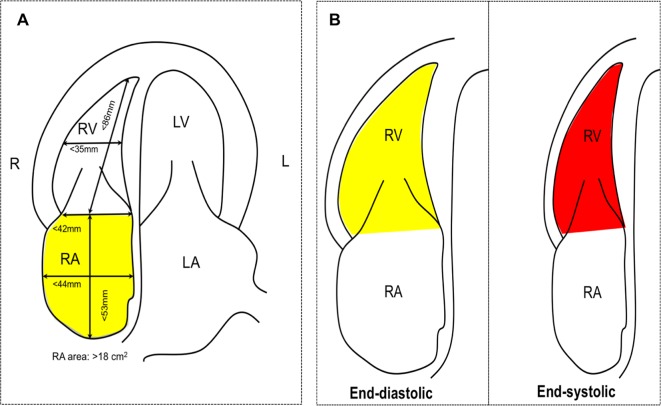

For the right heart, specific transthoracic echocardiographic measurements will be performed based on the Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of the Right Heart in Adults from the American Society of Echocardiography that are endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography.18 Specifically, right atrial (RA) dimension will be assessed using RA area (normal <18 cm2), RA length (normal <53 mm) and RA diameter (normal <44 mm). Right ventricular (RV) dimension will be estimated at the base (normal: <42 mm) and at the mid-level (normal: <35 mm) as well as the longitudinal dimension (normal: <86 mm) at end diastole from an RV-focused, apical four-chamber view with images demonstrating the maximum diameter of the RV without foreshortening (figure 2). An additional RV dimension at the RV outflow tract (RVOT) will be measured: (1) proximal RVOT diameter at the left parasternal long-axis view for the proximal portion of the RVOT (normal <33 mm) and (2) distal RVOT diameter at the left parasternal short-axis view demonstrating RVOT at the level of the pulmonic valve (normal <27 mm) (figure 2). RV wall thickness will be measured at the left parasternal view in diastole (normal <5 mm). In addition, RV systolic function will be assessed using (1) tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and RV fractional area change (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Echocardiography view. (A) Apical four-chamber view for right atrial and ventricular dimension and (B) right ventricular fractional area change. Yellow area: RV end-diastolic area; red area: RV end-systolic area. . LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; RA, right atrial; RV, right ventricular.

Right ventricular systolic pressure will be determined using continuous-wave Doppler echocardiography. Additional parameters to estimate RA will include (1) inferior vena cava diameter and (2) caval index which measures the respiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava.19 20 Additional echocardiographic signs of pulmonary hypertension include (1) dilated RV with RV to left ventricular basal diameter >1.0; (2) flattening of the interventricular septum; (3) dilated pulmonary artery; (4) dilated inferior vena cava; and (5) dilated RA. The echocardiographic probability of pulmonary hypertension will be classified as low, intermediate or high according to the 2015 European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension5 (table 2).

Table 2.

Echocardiographic probability of pulmonary hypertension5

| RVSP (mm Hg) | Peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity (m/s) | Other ECHO PAH sign | ECHO probability of PAH |

| 31 | 2.8 or not measurable | No | Low |

| 31 | 2.8 or not measurable | Yes | Intermediate |

| 32–46 | 2.9–3.4 | No | Intermediate |

| 32–46 | 2.9–3.4 | Yes | High |

| >46 | >3.4 | Not required | High |

ECHO, echocardiography; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure.

Right heart catheterisation and other investigations

In accordance with the guidelines,5 standard right heart catheterisation will be performed on participants with high echocardiographic probability of pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary hypertension is defined by a mean pulmonary artery pressure ≥25 mm Hg. The type of pulmonary hypertension will be further classified into group 1 to group 5 according to haemodynamic findings of the right heart catheterisation, clinical presentation, radiological investigation results and other pathological findings.5 PAH, also known as group 1 pulmonary hypertension, is defined by a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure ≤15 mm Hg and PVR >3 Wood units in the absence of significant left-sided heart disease, severe lung disease or chronic thromboembolic disease. For those who have PAH diagnosed, additional work-up will be performed to look for other contributory factors of PAH, including connective tissue disorder, HIV infection and chronic liver disease.

Study measures

The primary measures will be the prevalence of PAH in methamphetamine users. The secondary measures will be the risk factors for occurrence of PAH and prognostic performance and the final prediction model for PAH in methamphetamine users.

Sample size calculation

As there are no clinical data to enable estimation of the prevalence of pulmonary hypertension among methamphetamine users, a convenience sample will be used in the SOPHMA study. In 2017, the number of reported methamphetamine users in Hong Kong was 1727. Given that the estimated proportion of dependent users in a specialist substance abuse clinic is approximately 10%–20%, the target sample size will be 400.

Patient and public involvement

The study design was informed by discussion with management and practitioners of substance abuse services in Queen Mary Hospital, Castle Peak Hospital and Kwai Chung Hospital. The study design relied on their advice, as they have both close interactions with the patients and understanding of their medical conditions, and can represent patients’ wishes and medical needs. Their advice also determined our patient recruitment as well as result dissemination strategies.

Once the study is completed, we will disseminate our findings to the study participants by immediate feedback. Patients who are diagnosed to have PAH will be referred to local cardiology clinics for long-term follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables will be expressed as mean±SD. Statistical comparisons between methamphetamine users with and without PAH will be performed using Student’s t-test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. HR and 95% CIs for each variable to predict PAH will be determined using a multivariate Cox regression model with a p value <0.1 for inclusion. The prognostic performance of models in predicting PAH will be assessed using c-statistics. The c-statistics for receiver operating characteristic curve will be calculated using Analyse-It for Excel, with the Delong-Delong comparison for c-statistics. A p value <0.05 will be considered significant. Calculations will be performed using SPSS (V.12.0) and MedCal (V.13.1.2) software.

Ethics and dissemination

Written consent will be obtained from each participant and the study will be performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

PAH is a devastating, often life-threatening condition. In randomised control trials, new pharmacological treatments specifically targeting the molecular pathway of PAH have been shown to improve the morbidity and mortality of patients with PAH. Nonetheless, in real-world clinical registries, the prognosis of PAH remains poor. This is at least partly related to the delay in diagnosis. Early diagnosis of PAH is associated with improved long-term survival. As a result, detection of PAH in high-risk patients such as those with connective tissue disease12 has been regarded as a crucial next step to further improve the clinical outcomes. In the DETECT study of patients with systemic sclerosis, a multimodal approach that included echocardiography and biomarker was shown to be a sensitive, non-invasive means to identify PAH with minimal false negative results,8 and is recommended for screening of PAH in patients with systemic sclerosis.5 Nonetheless, apart from the setting of systemic sclerosis, systematic screening has not been recommended for other candidate patient groups potentially at high risk of PAH.

In the REVEAL registry, drug-induced PAH accounted for 10.5% of all cases of pulmonary hypertension.6 Historically, drugs used in the treatment of anorexia that have a chemical structure similar to amphetamines such as aminorex, fenfluramine, benfluorex and phenylpropanolamine have been shown by several epidemiological studies to be associated with the development of PAH. Illicit use of methamphetamine, currently classified as a ‘likely’ cause of drug-induced PAH by international guidelines,5 has been reported in 33.8 million individuals globally.1 Nonetheless, due to the unknown prevalence of PAH in methamphetamine users, it remains uncertain whether a systematic screening approach is appropriate to detect PAH in the early asymptomatic phase. Experience obtained from PAH screening in systemic sclerosis may serve as a model for PAH screening among methamphetamine users.

In this cross-sectional screening study, we will apply a current guideline-recommended echocardiography-based PAH screening algorithm to a cohort of unselected methamphetamine users. The strength of the SOPHMA study is that we will be the first group to use an established systematic approach to screen for PAH and study the risk factors for PAH among methamphetamine users. The weakness of this study is that only those with intermediate or high echocardiographic probability of PAH will undergo right heart catheterisation. This is because right heart catheterisation is not without risk, and current guidelines advocate limiting the procedure to those with intermediate or high probability of PAH based on echocardiographic measurements.5 The major drawback of this approach is that false negative results based on a low echocardiographic probability of PAH may underestimate the ‘true’ prevalence of PAH in methamphetamine users. Nevertheless, we believe that the false negative rate will be low since the DETECT study confirmed that non-invasive assessment is capable of identifying PAH in patients with systemic sclerosis with minimal false negatives.8

The SOPHMA study will provide information about the prevalence of and risk factors for the occurrence of PAH in methamphetamine users, followed by development of a prediction model. Our results will provide scientific evidence to enable psychiatric and cardiovascular professional bodies to establish universal guidelines for the screening of PAH among patients with methamphetamine use disorder, and form the foundation for academia to study the mechanisms, treatment and outcomes of methamphetamine-associated PAH. In addition, symptoms of PAH, such as reduced exercise tolerance and fatigability, are frequently attributed by patients and healthcare professionals to methamphetamine use, which can partly explain the exceptionally advanced disease status at diagnosis and poor clinical outcomes of methamphetamine-associated PAH.9 21 The results of this study will alert patients and healthcare providers to this serious complication of methamphetamine use, such that patients who develop suspicious symptoms will promptly report and be referred for specialist assessment. Our results will also benefit the society by raising public awareness of this debilitating and potentially lethal consequence of methamphetamine use.

There are five key audiences for this research: (1) psychiatric and cardiovascular professional bodies; (2) academia; (3) healthcare providers; (4) participating methamphetamine users; and (5) the general public. We will use multiple vehicles to disseminate the results of this study to our targeted audiences. First, we will present our research findings at international medical conferences and publish our results in peer-reviewed journals. Second, we will dispense information leaflets, accompanied by inperson discussion and immediate feedback to our study participants. Third, we will hold a press conference, followed by publication of a series of feature reports in key news media, in order to announce our results to the general public. This proactive dissemination strategy will ensure effective dissemination of our results and is a crucial part of efforts to improve prevention and management of the condition.

In summary, the SOPHMA study will explore the application of the PAH screening strategy that is currently recommended for high-risk patients in methamphetamine users. The findings of this study will provide the necessary evidence for professional bodies to establish universal guidelines for screening of PAH in methamphetamine users.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: This study was initially designed by C-WS, W-CC and AKKC. DH and PHC contributed by performing literature review, and YC and JJH jointly prepared the manuscript. C-KT, W-WL and ML have given invaluable comments and suggestions regarding the study design, taken into account the logistics and feasibility of the study, and result dissemination strategies. JJH was responsible for coordinating all parties, holding meetings and discussions, as well as incorporating all comments into the manuscript. All authors contributed to revision and critical appraisal of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Hong Kong and Hong Kong West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong (No. UW 19-359).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. (UNODC) UNOoDaC. World Drug Report 2013. Vienna: United Nations, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Panenka WJ, Procyshyn RM, Lecomte T, et al. . Methamphetamine use: a comprehensive review of molecular, preclinical and clinical findings. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;129:167–79. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schaiberger PH, Kennedy TC, Miller FC, et al. . Pulmonary hypertension associated with long-term inhalation of "crank" methamphetamine. Chest 1993;104:614–6. 10.1378/chest.104.2.614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chin KM, Channick RN, Rubin LJ. Is methamphetamine use associated with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension? Chest 2006;130:1657–63. 10.1378/chest.130.6.1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. . 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McGoon MD, Miller DP. REVEAL: a contemporary US pulmonary arterial hypertension registry. Eur Respir Rev 2012;21:8–18. 10.1183/09059180.00008211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Launay D, Sitbon O, Hachulla E, et al. . Survival in systemic sclerosis-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1940–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coghlan JG, Denton CP, Grünig E, et al. . Evidence-based detection of pulmonary arterial hypertension in systemic sclerosis: the DETECT study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1340–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zamanian RT, Hedlin H, Greuenwald P, et al. . Features and outcomes of methamphetamine-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197:788–800. 10.1164/rccm.201705-0943OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khanna D, Gladue H, Channick R, et al. . Recommendations for screening and detection of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:3194–201. 10.1002/art.38172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tselios K, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus and pulmonary arterial hypertension: links, risks, and management strategies. Open Access Rheumatol 2017;9:1–9. 10.2147/OARRR.S123549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang D, Cheng YY, Chan PH, et al. . Rationale and design of the screening of pulmonary hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus (SOPHIE) study. ERJ Open Res 2018;4 10.1183/23120541.00135-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Battle DE. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM). Codas 2013;25:191–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheitlin MD, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, et al. . ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 Guideline Update for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:1091–110. 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00685-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Helmcke F, Nanda NC, Hsiung MC, et al. . Color doppler assessment of mitral regurgitation with orthogonal planes. Circulation 1987;75:175–83. 10.1161/01.CIR.75.1.175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evangelista A, Garcia-Dorado D, Garcia del Castillo H, et al. . Cardiac index quantification by Doppler ultrasound in patients without left ventricular outflow tract abnormalities. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;25:710–6. 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00456-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dubrey SW, Falk RH. Optimal number of beats for the doppler measurement of cardiac output in atrial fibrillation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1997;10:67–71. 10.1016/S0894-7317(97)80034-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. . Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the american society of echocardiography endorsed by the european association of echocardiography, a registered branch of the european society of cardiology, and the canadian society of echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685–713. quiz 86-8 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kircher BJ, Himelman RB, Schiller NB. Noninvasive estimation of right atrial pressure from the inspiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava. Am J Cardiol 1990;66:493–6. 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90711-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Siu CW, Zhang XH, Yung C, et al. . Hemodynamic changes in hyperthyroidism-related pulmonary hypertension: a prospective echocardiographic study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1736–42. 10.1210/jc.2006-1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao SX, Kwong C, Swaminathan A, et al. . Clinical characteristics and outcome of methamphetamine-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension and dilated cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:209–18. 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.