Abstract

Background

Pharmacy syringe access may be an opportunity to provide HIV prevention resources to persons who inject drugs (PWID). We examined the impact of a pharmacy-randomized intervention to reduce injection risk among PWID in New York City.

Methods

Pharmacies (n=88) were randomized into intervention, primary control, and secondary control arms. Intervention pharmacies received in-depth harm reduction training, recruited syringe customers who inject drugs into the study, and provided additional services (i.e., HIV prevention/medical/social service referrals, syringe disposal containers, and harm reduction print materials). Primary control pharmacies recruited syringe customers who inject drugs and did not offer additional services, and secondary control pharmacies did not recruit syringe customers (and are not included in this analysis) but participated in a pharmacy staff survey to evaluate intervention impact on pharmacy staff. Recruited syringe customers underwent a baseline and 3-month follow-up ACASI. The intervention effect on injection risk/protective behavior of PWID was examined.

Results

A total of 482 PWID completed baseline and follow-up surveys. PWID were mostly Hispanic/Latino, male, and mean age of 43.6 years. After adjustment, PWID in the intervention arm were more likely to report always using a sterile syringe vs. not (PR=1.24; 95% CI: 1.04–1.48) at 3-month follow-up.

Conclusions

These findings present evidence that expanded pharmacy services for PWID can encourage sterile syringe use which may decrease injection risk in high HIV burdened Black and Latino communities.

Keywords: persons who inject drugs (PWID), HIV prevention, structural interventions, pharmacies, risk behavior

1. INTRODUCTION

One of the most successful HIV prevention efforts to date has been increased access to sterile syringes for the purposes of injecting drugs when cessation of drug use is unattainable (Des Jarlais et al., 2009; Institute of Medicine, 2006). Despite the successes of syringe access through syringe exchange programs, racial disparities in HIV have persisted with Black and Latino individuals who inject drugs carrying a disproportionately higher burden of HIV than their White counterparts (Des Jarlais et al., 2009; Kottiri et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2013). In 2001, the Expanded Syringe Access Program (ESAP) allowed the legal sale of syringes without a prescription in pharmacies in New York State to help reduce blood-borne disease transmission among persons who inject drugs (PWID). Racial/ethnic disparities in ESAP participation has been observed with Black and Latino PWID reporting lower rates of pharmacy use as a syringe source than whites when the law was initially passed (Cooper et al., 2009; Fuller et al., 2002).

To address this disparity, multilevel-targeted interventions in New York City (NYC) aimed at improving pharmacy use were implemented and showed positive intervention effects. For example, targeting PWID, pharmacy staff, pharmacy practice, and community norms revealed increased pharmacy use, particularly among Black PWID (Fuller et al., 2007; Rudolph et al., 2010). Building upon these successes, a large-scale pharmacy-randomized trial was implemented with the goal of expanding pharmacy services to PWID by offering HIV prevention, medical, and social services information during the syringe sale transaction (Pharmacy As Resources Making Links to Community Services “PHARM-Link” study). The overall goal of PHARM-Link was to evaluate the impact of training pharmacy staff in HIV prevention and harm reduction such that pharmacy practice extended into HIV prevention during the syringe sale transaction with PWID and examining this new pharmacy training and practice on two outcome categories: 1) pharmacy staff and practice, and 2) injection behaviors among PWID. An intervention effect was observed among pharmacy staff in the intervention pharmacies compared to those in the control pharmacies, namely increased ESAP support (Crawford et al., 2013) and decreased belief that selling syringes to PWID causes community loitering (Crawford et al., 2014). In this paper, we will present the PHARM-Link intervention impact on the second outcome category, injection behaviors among PWID.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

ESAP-registered pharmacies were selected from disadvantaged neighborhoods in Upper Manhattan, Lower Manhattan, Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. Neighborhood selection, ESAP-pharmacy eligibility, and recruitment have been described elsewhere (Rivera et al., 2010). In brief, 325 pharmacies were screened, 172 were eligible (i.e., willingness to sell nonprescription syringes without additional requirements, at least one new syringe customer per month, and at least one new syringe customer who becomes a regular customer), 31 did not maintain eligibility, and 11 declined to participate following the screener yielding 130 pharmacies with all pharmacy staff interacting with syringe customers agreeing to undergo a baseline survey. A total of 42 pharmacies declined to participate resulting in 88 ESAP-pharmacies randomized into three arms: intervention arm (n=26), primary control arm (n=29), and secondary control arm (n=33). Intervention pharmacies received in-depth harm reduction training and training on how to engage their syringe customers who inject drugs for study enrollment. In addition, they provided these customers with needle/syringe disposal Fitpacks® and print materials on HIV prevention and other medical/ social services specific to their community. Primary control pharmacies received training on how to engage their syringe customers who inject drugs to schedule appointments for study enrollment but did not provide these customers with any additional services. Secondary control pharmacies underwent surveys only and did not engage any customers for enrollment or receive training of any sort. While there were slightly fewer pharmacies in the intervention arm, pharmacy and pharmacy staff characteristics did not differ by attrition (e.g., race gender, position, and pharmacy location).

At the point of syringe sale, pharmacy staff in the intervention and primary control arms were trained in how to discreetly describe the study to their non-prescription syringe customers and if customers expressed interest in participating, to offer a study appointment (within one week of recruitment). At the study appointment, research staff met the participant at the pharmacy and escorted them to a nearby eatery, park, or library for study activities. If the participant was at least 18 years of age (ascertained through photo identification) the participant was considered eligible and underwent informed consent and a 45-minute Audio Computer Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) on a study laptop using touchscreen technology in a private area of the pharmacy or a nearby café. The survey, available in both English and Spanish, ascertained socio-demographic characteristics, drug use history, HIV risk behaviors, syringe access and disposal, drug treatment history, and use of case management for social services utilization. Participants who reported injection of an illicit drug within the past 6 months were eligible for a 3-month follow-up ACASI survey. Participants were compensated $20 and a roundtrip Metrocard for completion of the baseline survey and $25 for completion of the follow-up survey. Baseline data were collected between March 2009 and October 2010. The PHARM-Link study was approved by the institutional review boards of Columbia University Medical Center and the New York Academy of Medicine.

2.2. Measures

The outcomes of interest were as follows: HIV testing uptake, pharmacy syringe purchase frequency and barriers, safe syringe disposal, and drug abuse treatment/ medical care utilization reported at three-month follow-up. The main predictor of interest was pharmacy arm (intervention vs. primary control). Socio-demographic characteristics were considered as potential confounders and included sex (male vs. female), age (continuous), race/ethnicity (Black vs. White/other, Hispanic/Latino vs. White/other), education level (high school graduate or equivalent vs. less than a high school graduation/equivalent), homelessness in past three months (yes vs. no), full or part-time employment in past three months (yes vs. no), and baseline self-reported HIV status (positive vs. negative/unknown).

2.2.1. Injection risk/protective behaviors

At baseline and three-month follow-up, participants were asked their frequency of: illicit drug injection, receptive syringe sharing, non-receptive syringe sharing, and 100% sterile syringe use (i.e., always using a sterile syringe and not reusing the same syringe). Responses were asked using a likert scale (always, more than half the time, half the time, less than half the time, never) and dichotomized as ever vs. never for sharing variables and always vs. not always for the 100% syringe use variable based on the past 3 months.

2.2.2. HIV testing uptake

Participants were asked if they were tested for HIV in the past three months (yes vs. no).

2.2.3. Syringe exchange and purchases

Participants were asked about their syringe sources in the past three months and the frequency of using each source indicated. Frequency of syringe exchange program use, pharmacy syringe purchases (at least weekly vs. less than weekly), pharmacy as the primary syringe source (most frequent syringe source vs. not), and having encountered any barriers to pharmacy syringe purchases in the past three months (yes vs. no) were examined. The following syringe purchase barriers were considered: asked to sign a logbook, asked what the syringes would be used for, declined a single syringe purchase, declined any type of syringe purchase, and charged more than $1.00 for a single syringe (yes vs. no).

2.2.4. Syringe disposal

Safe syringe disposal practices was ascertained by the question, „In the past three months, when you finished using a needle or syringe, what did you do with it when you were ready to get rid of most of the time?‟. Safe syringe disposal was defined as either 1) bringing the needle or syringe to a syringe exchange program (SEP), hospital, nursing home, clinic or health department, doctor‟s office, or pharmacy or 2) throwing the needle or syringe away in a sharps container, Fitpacks®, soda/laundry bottle, red medical container/ sharps box, or red disposal mailbox. Safe syringe disposal in the past three months was included in analyses as a dichotomous variable (yes vs. no).

2.2.5. Medical care access

In terms of medical care access, we obtained current health insurance status (insured vs. uninsured) and having a usual source of care (yes vs. no). We also ascertained drug treatment uptake (excluding detoxification), detoxification uptake, and any case management services uptake in the past three months (yes vs. no).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The analysis was restricted to those who completed both baseline and three-month follow-up surveys. Baseline differences by study arm were calculated using chi-squares for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. To test pre/post differences in outcomes of interest, McNemar‟s tests were used. In order to test whether there was an intervention effect on the outcomes of interest, unadjusted associations between study arm and outcomes of interest at three months were obtained. For associations with p<0.10 we used log-binomial regression to obtain prevalence ratios of non-rare study outcomes and logistic regression for rare study outcomes at three-month follow-up between study arms using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering of participants within pharmacies while adjusting for baseline measures of the outcome and potential confounders. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3.

3. RESULTS

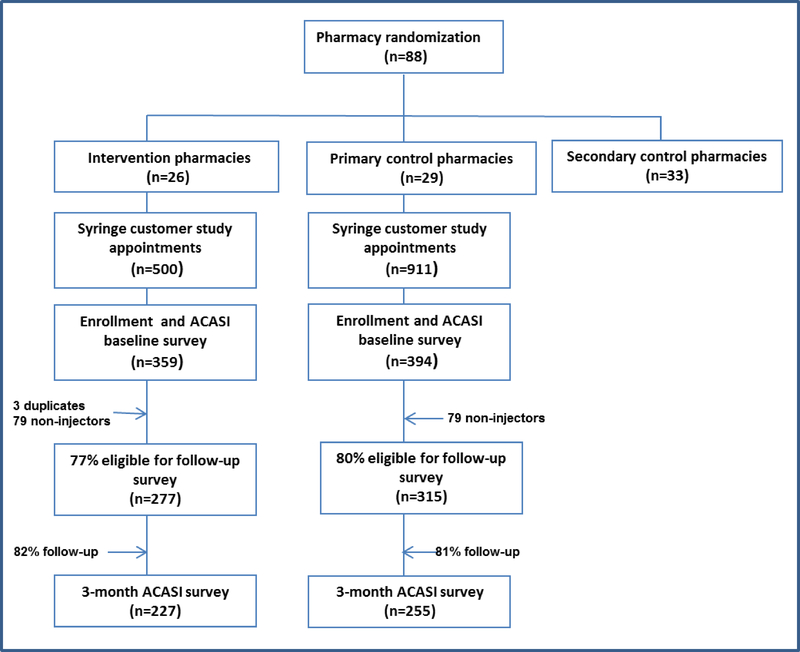

Figure 1 depicts detail on study enrollment and retention by study arm. A total of 1411 study appointments were made, of which 753 participants were enrolled and completed a baseline survey. Of those that completed the baseline survey, 78.9% (n=592) reported injection in the past 6 months and were eligible for the follow-up survey. There was a follow-up rate of 81.4% with a total of 482 participants completing the follow-up survey. Among those who were lost to follow-up, those from the control arm were less likely to have health insurance than those from the intervention arm; there were no difference by study arm.

Figure 1:

Study enrollment and retention by study arm, PHARM-Link, 2009–2010

Participants were mostly male (68.7%), Hispanic/Latino (51.1%), and unemployed (86.9%) with a mean age of 43.6 years. At baseline, participants in the intervention arm were more likely to be employed (p<0.0001) and less likely to have used case management (p=0.0220) in the past three months. There were no other baseline differences by study arm.

Pre/post differences are shown in Table 1 which includes two comparisons: (1) differences between pre/post measures by study arm (i.e., comparison within study arm), and (2) differences between 3-month follow-up measures by study arm (i.e., comparison between study arm) with the latter directly informing the subsequent final adjusted models. In the primary control arm, the frequency of participants purchasing syringes from pharmacies and using pharmacies as a primary syringe source significantly decreased at follow-up while these practices remained unchanged in the intervention arm. Participants in the intervention arm also indicated an increase in report of always using a sterile syringe where no change was seen in the primary control arm at follow-up. Risk behaviors improved in both arms at follow-up, namely drug injection, receptive syringe sharing, and non-receptive syringe sharing decreased, and HIV testing uptake increased. Both baseline and follow-up results indicated high drug treatment access overall (75–85%), remaining unchanged over time in both study arms. Finally, while safe syringe disposal was modest ranging between 33–46% for participants in each arm, there was a significant increase observed in the intervention arm (33–41%; p<0.04), and no change in the control arm. Fitpacks® (provided to syringe customers in the intervention arm) were rarely used and remained unchanged across each study arm, over time.

Table 1.

Pre- and post-intervention risk behaviors, syringe practices, and medical care access among PWID by study arm, PHARM-Link, 2009–2011.

| Control Arm (n=255) |

Intervention Arm (n=227) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3-month | Baseline | 3-month | ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | Pre/post p-value | n (%) | n (%) | Pre/post p-value | I vs Cc p-value | |

| Demographics | |||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 177 (69.4) | 154 (67.8) | |||||

| Female | 77 (30.2) | 70 (30.8) | |||||

| Transgender | 1 (0.39) | 3 (1.3) | |||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 125 (49.2) | 121 (53.3) | |||||

| Black | 78 (30.7) | 60 (26.4) | |||||

| White/Other | 51 (20.8) | 46 (20.3) | |||||

| Age (mean, SD) | 43.3 (9.3) | 44 (9.2) | |||||

| High school graduate | 157 (61.6) | 150 (66.1) | |||||

| HIV positive | 37 (14.5) | 30 (13.5) | |||||

| Homeless | 88 (34.5) | 64 (25.1) | 0.0012 | 63 (27.8) | 49 (21.6) | 0.0704 | 0.3636 |

| Employed | 19 (7.5) | 14 (5.5) | 0.4049 | 44 (19.4) | 23 (10.1) | <.0001 | 0.0576 |

| Risk behaviorsa | |||||||

| Injected drugs | 251 (98.4) | 203 (79.6) | <.0001 | 223 (98.2) | 179 (78.9) | <.0001 | 0.8387 |

| Daily drug injection | 85 (33.3) | 58 (22.8) | <.0001 | 74 (32.6) | 54 (24.0) | 0.0078 | 0.7456 |

| Receptive syringe sharing | 54 (21.2) | 35 (13.7) | 0.0110 | 44 (19.3) | 20 (8.8) | <.0001 | 0.0903 |

| Non-receptive syringe sharing | 69 (27.1) | 50 (19.6) | 0.0204 | 64 (28.2) | 40 (17.6) | 0.0012 | 0.5764 |

| 100% sterile syringe useb | 127 (50.8) | 99 (48.8) | 0.5716 | 118 (52.7) | 113 (63.1) | 0.0257 | 0.0048 |

| HIV test (among negatives only) | 100 (46.7) | 149 (69.3) | <.0001 | 101 (51.8) | 130 (66.3) | 0.0015 | 0.5187 |

| Syringe disposal and purchasea,b | |||||||

| Safe syringe disposal | 96 (39.5) | 91 (46.4) | 0.1263 | 74 (33.5) | 72 (42.1) | 0.0400 | 0.4057 |

| Fitpack use | 2 (0.80) | 6 (3.0) | 0.2188 | 12 (5.4) | 7 (3.9) | 0.7744 | 0.6075 |

| Syringe exchange program use | 141 (55.7) | 121 (59.6) | 0.3222 | 109 (48.7) | 100(55.9) | 0.1352 | 0.4601 |

| Weekly pharmacy syringe purchase | 150 (59.8) | 97 (47.8) | <.0001 | 123 (55.2) | 89 (49.7) | 0.1439 | 0.7054 |

| Pharmacy syringe purchase barrier | 69 (31.2) | 68 (39.5) | 0.5044 | 63 (30.9) | 49 (30.8) | 0.7552 | 0.0974 |

| Pharmacy primary syringe source | 139 (55.4) | 91 (45.3) | 0.0043 | 112 (50.5) | 96 (54.2) | 0.4426 | 0.0836 |

| Medical care access | |||||||

| Current health insurance | 207 (81.2) | 216 (85.0) | 0.1539 | 197 (86.8) | 202 (89.0) | 0.4049 | 0.2002 |

| Usual source of care | 159 (62.4) | 170 (66.7) | 0.2543 | 141 (62.1) | 155 (68.9) | 0.0869 | 0.6033 |

| Received drug treatmenta (excluding detox) | 210 (82.7) | 190 (74.5) | 0.0031 | 191 (84.5) | 178 (78.4) | 0.0488 | 0.3140 |

| Received detoxa | 50 (19.6) | 36 (14.1) | 0.0649 | 28 (12.4) | 30 (13.2) | 0.8555 | 0.7738 |

| Received case managementa | 175 (68.6) | 161 (63.1) | 0.1702 | 133 (58.6) | 128 (56.4) | 0.6646 | 0.1312 |

in past 3 months

among PWID who injected in past 3 months only

I vs C p-values represent between group differences of the intervention and control study arms at 3-month study visit.

In unadjusted analyses comparing outcomes at three-month follow-up by study arm, participants in the intervention arm were more likely to report 100% sterile syringe use and somewhat less likely to experience a barrier at a pharmacy syringe sale. Other borderline associations by study arm included employment, receptive syringe sharing, and using a pharmacy as primary syringe source.

Based on the unadjusted comparisons, four injection risk/protective behaviors (i.e., receptive syringe sharing, pharmacy as primary syringe source, 100% sterile syringe use, and experiencing a pharmacy syringe purchase barrier) were selected as outcome measures to further examine the presence of an independent intervention effect given the strong measurable differences observed. All outcomes were examined after adjustment for their baseline value, employment status, and accounting for clustering. Those who reported 100% sterile syringe use were more likely to be in the intervention arm (PR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.04–1.48) than those who did not report 100% sterile syringe use (Table 2). Borderline associations remained between two outcomes of interest: receptive syringe sharing and intervention status (OR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.33–1.09), and use of a pharmacy as a primary syringe source and intervention status (PR: 1.20; 95% CI: 0.99–1.44) (Table 2). Finally, no significant association was found between experiencing a pharmacy syringe purchase barrier and study arm.

Table 2.

Adjusted intervention effect on injection behavior outcomes among PWID, PHARM-Link, 2009–2010

| Receptive syringe sharing | Pharmacy primary syringe source | 100% sterile syringe use | Pharmacy syringe purchase barrier | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | |||

| Study arm: | ||||

| Intervention | 0.60 (0.33–1.09) | 1.20 (0.99–1.44) | 1.24 (1.04–1.48)* | 0.82 (0.62–1.09) |

| Control | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Adjusted for baseline value, baseline employment, and clustering of PWID within pharmacies

p<0.05

4. DISCUSSION

These data are among the few structural HIV prevention intervention studies where an independent intervention effect was observed with solid evidence of this effect being attributed to the intervention activities, given the randomized study design. One outcome in particular, 100% sterile syringe use, was significantly reported by PWID in intervention pharmacies where pharmacy staff were trained in HIV prevention and harm reduction to help extend pharmacy practice into delivery of HIV prevention and related services for PWID.

These data, coupled with our earlier intervention effect reported among pharmacy staff in the PHARM-Link study, provide strong evidence supporting the importance of targeting both individual behavior and structural features to enhance in intervention research and public health practice. For example, providing PWID with HIV prevention information and referrals during the syringe sale (i.e., individual intervention target), and training pharmacy staff in HIV prevention and harm reduction to help facilitate extension of pharmacy practice into HIV prevention and public health practice (i.e., structural intervention target) revealed complimentary intervention effects. Thus, the consistency of these multilevel data provide clear evidence supporting the likelihood of these observed effects being attributed to the intervention activities.

It is important to note a few limitations and features of this study. First, due to both practical and ethical reasons, we could not randomize individual PWID to study arms and instead, randomized the pharmacies. Interestingly, when comparing PWID by study arm, few differences surfaced including employment status which was accounted for during adjustment.

A second noteworthy drawback of this study is the short follow-up period of 3 months. It is unknown if these differences would sustain over time. Conversely, some risk or protective behaviors may not have had an opportunity to surface over a 3-month period. However, these data provide clear evidence supporting the utility of a structural, multilevel intervention to help facilitate individual uptake of and access to a public health prevention program.

A third limitation in this study is the reduced power to detect more than one adjusted intervention effect due to lower than expected sample yield of PWID (i.e., N=922 expected sample size). However, even in the presence of limited power (<80%), a significant intervention effect was observed with “always use of sterile syringes”, and a borderline significant effect was observed with “receptive syringe sharing”, and “use of pharmacies as a primary syringe source” (p<0.10).

Finally, the external validity of the study is worthy of more in-depth discussion. Pharmacies in high drug-active neighborhoods in New York City (NYC) are likely to be characterized by more public health-minded pharmacy staff given the extensive evaluations that have been conducted among ESAP pharmacies since the state program began (Amesty et al., 2012; Coffin et al., 2006; Fuller et al., 2002; New York Academy of Medicine, 2003). And yet, the observation of an intervention effect in the face of pharmacy selection bias and high baseline ESAP support is rather remarkable. Furthermore, while positive public health attitudes toward ESAP such as support for ESAP and belief in the importance of ESAP in preventing the spread of HIV have been relatively high among pharmacy staff in NYC (70%−80%) (Crawford et al., 2014, 2013, 2011), it is likely that the positive pharmacy attitudes were not what differentially impacted PWID by study arm. For example, both intervention and control pharmacies were trained in engaging PWID syringe customers and scheduling study appointments. Pharmacy randomization arms were better distinguished by the pharmacy “context”, namely the risk reduction study posters and pharmacy practices including provision of risk and harm reduction, medical, and social services information and referrals in the intervention pharmacies vs. no accompanying materials or information in the control pharmacies. These materials primarily included “Safety Insert Packets” or SIPS, a prevention package of harm reduction materials, condoms, and multilingual medical/social services information booklets – 1,423 were distributed throughout the intervention. This level of contact and discussion during the syringe sale may have enhanced rapport between pharmacy staff and syringe customers, which subsequently influenced the outcomes measured in this study.

In terms of public health impact, it is clear that continuing such activities in NYC is a sensible public health strategy given these empiric findings and should be considered for scale-up by local health departments. Yet, there may be some uncertainty in other states with similar pharmacy syringe access programs. While there is no reason to suspect that training pharmacy staff and extending pharmacy practice into HIV prevention would not similarly impact PWID in other states and municipalities, feasibility could be an issue if there are lower levels of pharmacy staff support (Hammett et al., 2014; Lutnick et al., 2012). However, other states in which evaluations are taking place have clear potential to realize similar increases in support for nonprescription syringe sales to PWID and an expanded pharmacy role into public health practice for their syringe customers who inject drugs (Hammett et al., 2014; Meyerson et al., 2013; Zaller et al., 2013). Pharmacies are frequently encountered in urban centers, and even moderate levels of support can still translate into a sizeable number of pharmacies serving as HIV prevention outlets. Thus, identifying supportive pharmacists is worthy of effort and exploration to help tackle individual and structural barriers to HIV prevention services for those who require these services most is warranted and long overdue.

Highlights.

Racial disparities in HIV burden persist among persons who inject drugs (PWID).

We conducted a pharmacy-randomized trial coupling HIV services with syringe buys.

At follow-up, we found a positive intervention effect on sterile syringe use.

Expanded pharmacy services may decrease injection risk in HIV burdened communities.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA022144). Ms. Rivera was funded by the National Institute on General Medical Sciences Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (5R25GM06245410).

The authors thank study participants for their time and research staff for their data collection efforts.

Author Disclosures

Role of Funding Source

This study was funded by National Institutes on Drug Abuse (1R01DA022144). Ms. Rivera was funded by the National Institute on General Medical Sciences Initiative for Maximizing Student Development (5R25GM06245410). NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Amesty S, Blaney S, Crawford ND, Rivera AV, Fuller C, 2012. Pharmacy staff characteristics associated with support for pharmacy-based HIV testing. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 52, 1–9, 472–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin PO, Blaney S, Fuller C, Vadnai L, Miller S, Vlahov D, 2006. Support for buprenorphine and methadone prescription to heroin-dependent patients among New York City physicians. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 32, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HL, Bossak BH, Tempalski B, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, 2009. Temporal trends in spatial access to pharmacies that sell over-the-counter syringes in New York City health districts: relationship to local racial/ethnic composition and need. J. Urban Health 86, 929–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ND, Amesty S, Rivera AV, Harripersaud K, Turner A, Fuller CM, 2013. Randomized, community-based pharmacy intervention to expand services beyond sale of sterile syringes to injection drug users in pharmacies in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 103, 1579–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ND, Amesty S, Rivera AV, Harripersaud K, Turner A, Fuller CM, 2014. Community impact of pharmacy-randomized intervention to improve access to syringes and services for injection drug users. Health Educ. Behav. 41, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford ND, Blaney S, Amesty S, Rivera AV, Turner AK, Ompad DC, Fuller CM, 2011. Individual- and neighborhood-level characteristics associated with support of in-pharmacy vaccination among ESAP-registered pharmacies: pharmacists‟ role in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in influenza vaccinations in New York City. J. Urban. Health 88, 176–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Hagan H, McKnight C, Perlman DC, Friedman SR, 2009. Persistence and change in disparities in HIV infection among injection drug users in New York City after large-scale syringe exchange programs. Am. J. Public Health 99 Suppl. 2, S445–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Ahern J, Vadnai L, Coffin PO, Galea S, Factor SH, Vlahov D, 2002. Impact of increased syringe access: preliminary findings on injection drug user syringe source, disposal, and pharmacy sales in Harlem, New York. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. (Wash). 42, S77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Galea S, Caceres W, Blaney S, Sisco S, Vlahov D, 2007. Multilevel community-based intervention to increase access to sterile syringes among injection drug users through pharmacy sales in New York City. Am. J. Public Health 97, 117–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett TM, Phan S, Gaggin J, Case P, Zaller N, Lutnick A, Kral AH, Fedorova EV, Heimer R, Small W, Pollini R, Beletsky L, Latkin C, Des Jarlais DC, 2014. Pharmacies as providers of expanded health services for people who inject drugs: a review of laws, policies, and barriers in six countries. BMC Health Serv. Res. 14, 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, 2006. Preventing HIV Infection among Injecting Drug Users in High Risk Countries: An Assessment of the Evidence. National Academies Press, Washington DC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottiri BJ, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Curtis R, Des Jarlais DC, 2002. Risk networks and racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of HIV infection among injection drug users. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 30, 95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutnick A, Case P, Kral AH, 2012. Injection drug users‟ perspectives on placing HIV prevention and other clinical services in pharmacy settings. J. Urban Health 89, 354–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson BE, Ryder PT, von Hippel C, Coy K, 2013. We can do more than just sell the test: pharmacist perspectives about over-the-counter rapid HIV tests. AIDS Behav. 17, 2109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York Academy of Medicine, 2003. New York State Expanded Syringe Access Demonstration Program Evaluation: Evaluation Report to the Governor and the New York State Legislation. New York City. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera AV, Blaney S, Crawford ND, White K, Stern RJ, Amesty S, Fuller C, 2010. Individual- and neighborhood-level factors associated with nonprescription counseling in pharmacies participating in the New York State Expanded Syringe Access Program. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 50, 580–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph AE, Standish K, Amesty S, Crawford ND, Stern RJ, Badillo WE, Boyer A, Brown D, Ranger N, Orduna JM, Lasenburg L, Lippek S, Fuller CM, 2010. A community-based approach to linking injection drug users with needed services through pharmacies: an evaluation of a pilot intervention in New York City. AIDS Educ. Prev. 22, 238–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C, Eisenberg M, Becher J, Davis-Vogel A, Fiore D, Metzger D, 2013. Racial disparities in HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among injection drug users and members of their risk networks. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 63 Suppl 1, S90–S94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaller ND, Yokell MA, Green TC, Gaggin J, Case P, 2013. The feasibility of pharmacy-based naloxone distribution interventions: a qualitative study with injection drug users and pharmacy staff in Rhode Island. Subst. Use Misuse 48, 590–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]