Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Little is Known about real-world facility-level preferences for cardiac resynchronization therapy devices with (CRT-D) and without (CRT-D) defibrillator backup. We quantify this variation at the facility level and exploit this variation to compare outcomes of patients receiving these 2 devices.

METHODS AND RESULTS:

Claims data from fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries were used to identify new CRT-P and CRT-D implants, 2006 to 2012. We modeled factors associated with receipt of each device, and compared mortality, hospitalizations, and reoperations for patients receiving each using both logistic regression and instrumental variable analysis to account for confounding. Among 71 459 device recipients (CRT-P, 11 925; CRT-D, 59 534; 31% women), CRT-P recipients were older, more likely to be women, and had more comorbidities. Variation in device selection among facilities was substantial: After adjustment for patient characteristics, the odds of receiving a CRT-P (versus CRT-D) device were 7.6× higher for a patient treated at a facility in the highest CRT-P use quartile versus a facility in the lowest CRT-P use quartile. Logistic modeling suggested a survival advantage for CRT-D devices but with falsification end points indicating residual confounding. By contrast, in the instrumental variable analysis using facility variability as the proposed instrument, clinical characteristics and falsification end points were well balanced, and 1-year mortality in patients who received CRT-P versus CRT-D implants did not differ, while CRT-P patients had a lower probability of hospitalizations and reoperations in the year following implant.

CONCLUSIONS:

CRT-P versus CRT-D selection varies substantially among facilities, adjusted for clinical factors. After instrumental variable adjustment for clinical covariates and facility preference, survival was no different between the devices. Therefore, CRT-P may be preferred for Medicare beneficiaries considering new CRT implantation.

Keywords: cardiac resynchronization therapy, comorbidity, defibrillators, heart failure, Medicare

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is recommended for patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, a wide QRS complex, and symptomatic heart failure despite optimal medical therapy.1 CRT with or without defibrillator backup (CRT-D and CRT-P, respectively) both improve quality of life and reduce heart failure hospitalizations, but few studies have compared their relative impact on clinical outcomes in real-world populations.2 Despite this evidence gap and the higher costs and risk for complications with CRT-D devices,3 most patients in the United States receive CRT-D.4,5

Previous studies have documented variation in use of cardiac implantable electric devices, including variation across countries6,7 and the mediating role of geography in explaining racial differences in implantable cardio-verter-defibrillator (ICD) implants in the United States.8 Moreover, although facilities vary widely in use of single- and dual-chamber ICDs,9 less is known about factors that influence the choice between CRT-D and CRT-P in clinical practice. In a prior study, we obtained state level estimates of CRT-P implant rates in Medicare Advantage populations.5 Another study identified regional variation in CRT device selection,4 but was limited to inpatient procedures, which may differ from observation or outpatient cases.10 Accordingly, a more comprehensive assessment of variation in CRT choices and clinical outcomes among decision-making entities, such as facilities, is needed. These, more often than geographic units, are the targets of payment reform and quality improvement policies, which would also benefit from a clearer understanding of the comparative effectiveness of CRT-D versus CRT-P among older patients.

Thus, this study used claims from fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries to evaluate (1) CRT-D versus CRT-P implantation practice patterns at the facility and state levels and (2) the comparative effectiveness, in terms of survival, hospitalization, and reoperation rates, of CRT-D versus CRT-P.

METHODS

Data Sharing

The data, analytic methods, and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure. Because of the specific data use agreement applicable to this funded research, we are not able to make these available to outside parties for replication.

Data Source and Implant Identification

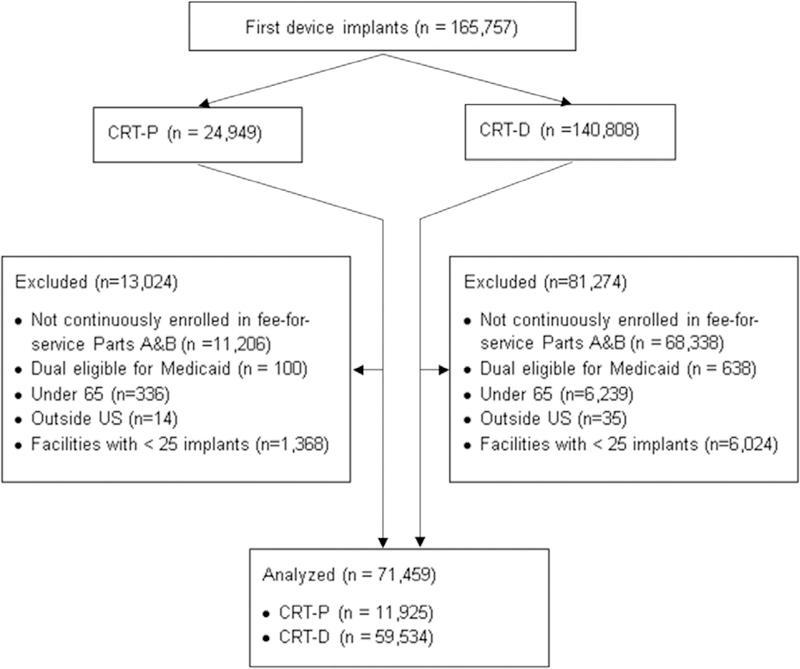

We obtained 100% inpatient and outpatient files, including facility and provider files, from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for 2005 to 2013 (Figure 1). We identified CRT-D and CRT-P implantation procedures using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and Current Procedural Terminology codes (see Appendix for details). First, we formed distinct clinical episodes, starting with an institutional claim that defined the setting (inpatient or outpatient) and dates of service. For inpatient episodes, we combined inpatient claims from the admission with carrier claims that occurred during the admission. For outpatient episodes, we similarly combined the institutional outpatient claim with carrier claims by date of service. Then, for each patient, we examined their first clinical episode (whether outpatient or inpatient) observed in the study period.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the sample creation process showing the numbers included and excluded by each criterion.

CRT-D indicates cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; and CRT-P, CRT pacemaker.

We excluded patients whose first episode included any codes that indicated removal, extraction, or revision (see Data Supplement) to identify patients with new implants only.5 We classified this first, new implant as CRT-D or CRT-P using ICD-9-CM and Current Procedural Terminology codes from all claims in the episode (CRT-P: 00.50±33207/8 and 33225; CRT-D: 00.51±33249 and 33225). Two implants of the same type in the same admission within 7 days were considered a single implant. If the 2 different devices were implanted in the same admission, within 7 days, we excluded the patient.

This study was deemed not human subjects research by the Health Care Policy Compliance Office at Harvard Medical School, in accordance with the Office of Human Research Administration, Harvard Longwood Medical Area policy, and federal regulations [45 CFR 46.102(f)]. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services granted approval for the use of the data under Data Use Agreement number 28630.

Study Population

Patients who received new CRT-P and CRT-D devices, as identified using the above procedure, were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). We excluded people with fewer than 12 months of preimplant and 12 months of postimplant continuous fee- for-service enrollment in parts A and B, limiting the study cohort to patients who received implants in 2006 to 2012. We excluded beneficiaries enrolled in Medicaid in the month of implant (dual eligible beneficiaries); beneficiaries who qualified for Medicare coverage because of disability and those aged <65; and excluded procedures at facilities performing fewer than 25 implants per year to ensure stable estimates of facility-level parameters.

Variables

Patient characteristics were measured from enrollment files and ICD-9-CM codes in the year before implantation. Demographics included year of implant, age at implant (categorized as 65–69, 70–74, 75–79 [reference group], 80–84, and 85 and older), sex, and race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, white [reference group], and other). Cardiac conditions included cardiac arrest, ischemic disease, arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, and conduction disorders. In addition, we computed the Charlson comorbidity score (see Appendix) and categorized each as 0, 1, 2, and ≥3.

Primary Study Outcomes

Hospitalizations in the year following implant were identified in Medicare claims. These were further classified as heart failure hospitalizations (primary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 428.x) and implant-related reoperations (generator reoperation, lead reoperation, pocket revision, or combinations of these; see Appendix). Deaths within 1 year were identified using enrollment files. This timeframe was selected for both outcomes to avoid loss to follow-up if patients transitioned out of fee-for-service coverage to Medicare Advantage programs.

Falsification Outcomes and Instrumental Variable Analysis

We anticipated that unobserved differences among patients receiving CRT-D and CRT-P devices might confound the outcome comparison in ways that logistic regression, which is limited only to known confounders, would not sufficiently address. Thus, we leveraged variation in facility-level tendency to use CRT-P versus CRT-D as an instrumental variable (IV), described in detail below.11

In addition, we specified 3 falsification outcomes, consistent with prior studies of cardiac implantable electric devices12: (1) discharge to nursing home (for inpatient implants only), (2) mortality at 30 days after implant, and (3) nontraumatic hip fracture in the year following implant (ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 820.xx or 733.14 and a related ICD-9-CM procedure code 78.55, 79.05, 79.15, 79.25, 79.35, or 79.65 or Current Procedural Terminology code 27230–27248). The goal is to use differences in these outcomes as a signal of bias because of residual con-founding.13 In this study, we chose hip fracture, discharge to nursing home, and 30-day mortality as outcomes unlikely to be affected by the choice of CRT-P versus CRT-D implant, but likely to reflect unobserved patient health status, a major concern as a source of bias in our analyses, because frail patients are more likely to receive CRT-P devices and also to experience the health outcomes of interest (eg, 1-year mortality).

Statistical Analysis

We computed descriptive statistics of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who receive CRT-P and CRT-D devices using proportions for categorical variables, compared using standardized mean differences.

To quantify factors associated with implantation of each device, we fit a logistic regression model for device type of patient i at facility j:

where dij=1 for CRT-P and 0 for CRT-D and x includes the patient characteristics described above. We assumed that the facility random effects come from a normal distribution To characterize variation in facility tendency to implant CRT-P versus CRT-D, we examined the estimated random effects from this model. We classified a facility as having a high tendency to use CRT-P (Cj = 1) if was significantly greater than 0. We present the results of this model as odds ratios and 95% CIs.

To quantify differences in outcomes (survival, all-cause hospitalizations, and heart failure hospitalizations) of patients who receive CRT-P versus CRT-D, we fit logistic regression models for each outcome (where yij=1 indicates occurrence of the outcome and 0 otherwise):

where states(j) is a fixed effect for the state in which facility j is located. We present the results of this model as odds ratios and 95% CIs.

These models rely on regression adjustment to account for confounders, that is, variables that affect both treatment (CRT-P versus CRT-D) and outcomes, such as age and health status. However, confounders that we do not observe, such as more detailed measures of health status, will bias these estimates. Therefore, we exploited the variation in each facility’s tendency to implant CRT-D versus CRT-P to reduce this confounding bias using an IV approach, similar to prior studies in cardiovascular outcomes research.14–16

To be valid, the proposed instrument (facility tendency to implant CRT-P) must satisfy 3 conditions. It must be related to treatment, have no direct causal relationship to the outcome, and be independent of unmeasured confounders of the treatment-outcome relationship. The first condition we demonstrate via a regression of device type on facility tendency, showing the facility tendency strongly predicts treatment received. The second 2 conditions are inherently untestable because they involve true causal relationships and unobserved confounders. In the Table of the Data Supplement, we compare the observable covariates across levels of the proposed instrument as in the Table for the actual treatment received. Although balance on the observables is not proof that the third assumption is met, it is reassuring to see good balance on observable patient characteristics in facilities with different tendencies to implant CRT-P versus CRT-D devices, with the possible exception of atrial fibrillation, which is more common in patients implanted at facilities that prefer CRT-P (48%) than in other facilities (42%). In the discussion section, we consider possible threats to the validity of our proposed instrument. In addition, to understand the possible impact of violations of these assumptions on our estimates, we fit the IV model to our 3 falsification outcomes. Any effects of CRT-P versus CRT-D on these outcomes indicate violations of the analysis assumptions because these outcomes should not be influenced by device type.

We fit the IV model using a 2-stage least squares approach, consistent with prior studies14–16 with the firststage model and second-stage model is the implant tendency estimated from the first stage. The coefficient βfac in the first-stage model quantifies the influence of facility tendency to implant CRT-P on the actual device received by a patient, conditional on patient characteristics, and thus signals the plausibility of the first assumption of the IV model. The coefficient βdev in the second-stage model quantifies the effect of device type (as identified from facility variation) on health outcomes.

All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The cohort consists of 71459 patients who received new implants in 2006 to 2012 of CRT-P (11 925) and CRT-D (59 534). The table summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort, both overall and separately for CRT-P and CRT-D recipients. Over-all, 31% were women, 60% were aged >75 years, and 93% were white. Characteristics that were more common among CRT-P recipients included age 80 years and older (54% versus 29%), female sex (44% versus 28%), atrial fibrillation (67% versus 39%), and arrhythmia (32% versus 26%). Characteristics more common among CRT-D recipients included ischemic disease (76% versus 62%) and cardiomyopathy (46% versus 31%). CRT-P implants increased over time: in 2006, only 10% of the sample received CRT-P devices; by 2012, that increased to 25%.

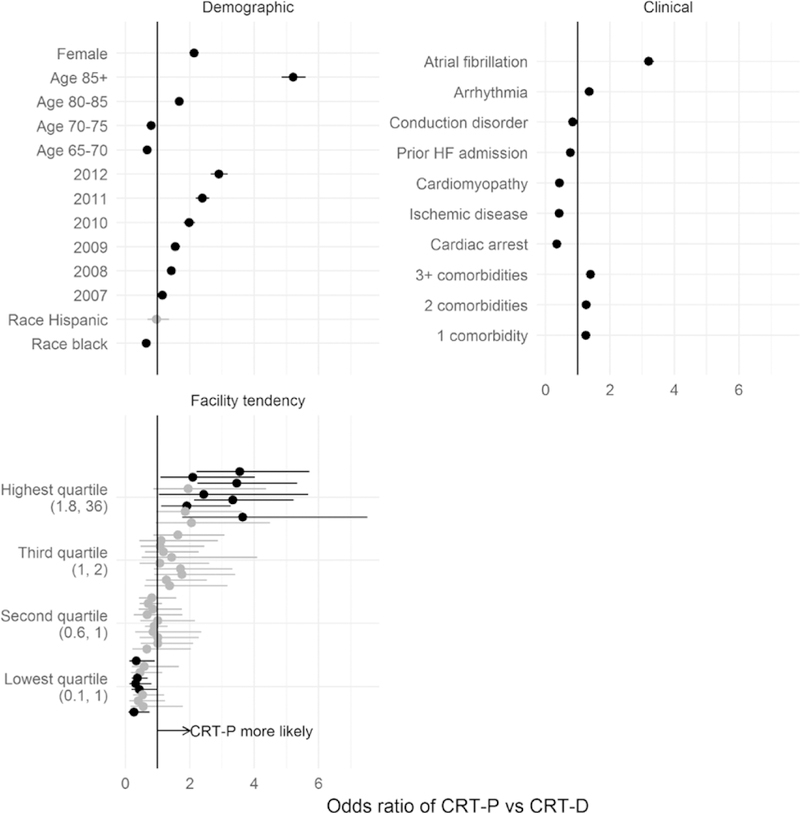

Factors Associated With Choice of Device

Because of the large sample size, all the differences were statistically significant except the difference between Hispanic and white (Figure 2). In addition to the differences noted above, patients who received CRT-P devices were more likely to have comorbidities and less likely to be black or have a history of conduction disorder, prior heart failure admission, and cardiac arrest.

Figure 2. Patient factors associated with receipt of cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) vs and defibrillator (CRT- D) device.

Odds ratios and 95% CIs are estimated from a logistic regression model that includes facility random effects. Intervals that exclude 1 are plotted in black. Estimated random effects for 10 randomly selected facilities from each quartile of the across-facility distribution are shown. Numbers in parentheses in the bottom left plot indicate the values of the odds ratios that define each quartile. HF indicates heart failure.

Variation in Tendency to Implant CRT-P Versus CRT-D Among Facilities

We categorized facilities into quartiles of case mix-adjusted rates of CRT-P versus CRT-D implantation (ie, their facility-level estimated random effects). Figure 2 shows 10 randomly selected facilities in each quartile. For 2 patients with the same characteristics, the odds of receiving a CRT-P (versus CRT-D) device were 7.6× higher for a patient treated at a facility in the highest quartile versus a facility in the lowest quartile. This effect was as large as that of the most important patient factors: For example, the odds of CRT-P implant were 7.7× higher in patients 85 years and older compared with those aged 65 to 70 years. The coefficient of variation (on the logit scale) of the facility tendency was −2.0.

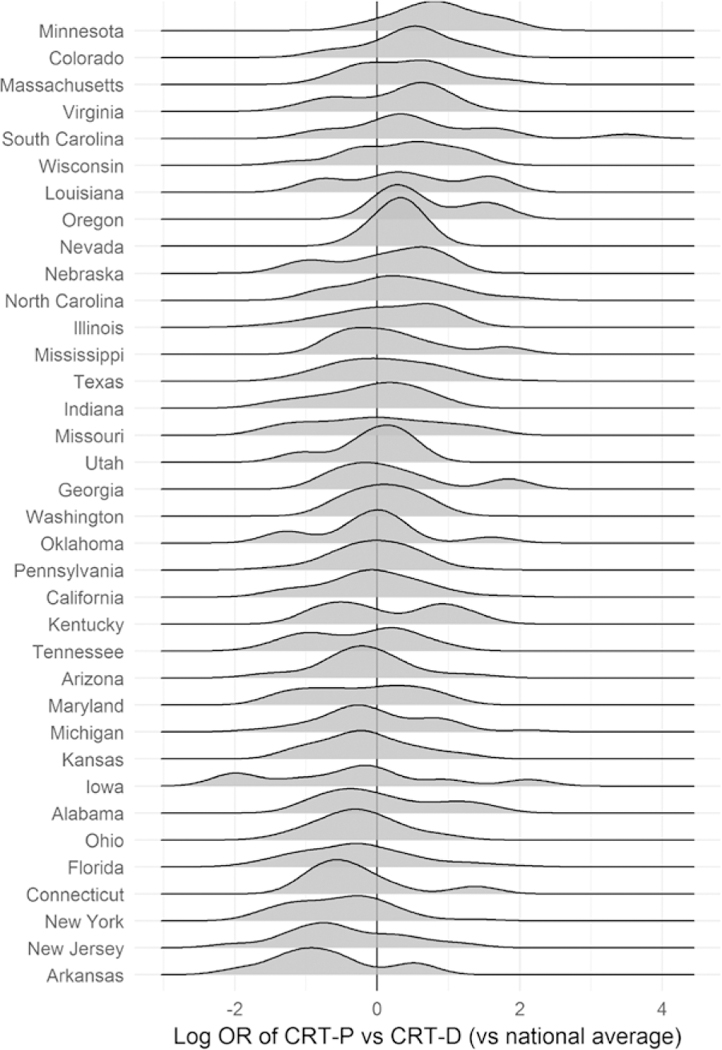

State-Level Variability in Device Selection

The variation across states was smaller than the variation across facilities, but across-state variation in median CRT-P rates spanned 77% of the distribution of across-facility variation (Figure 3). That is, moving from Arkansas’s median facility (the lowest state median at 0.4× the national average odds of CRT-P versus CRT-D) to Minnesota’s median facility (the highest state median at 2.4× the national average odds of CRT-P versus CRT- D) was equivalent to moving from an 11th percentile facility to an 88th percentile facility in the whole nation.

Figure 3. Distribution of facility tendency to implant CRT-P (vs CRT-D) in states with at least 5 facilities.

CRT-D indicates cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators; CRT-P, CRT pacemaker; and OR, odds ratio.

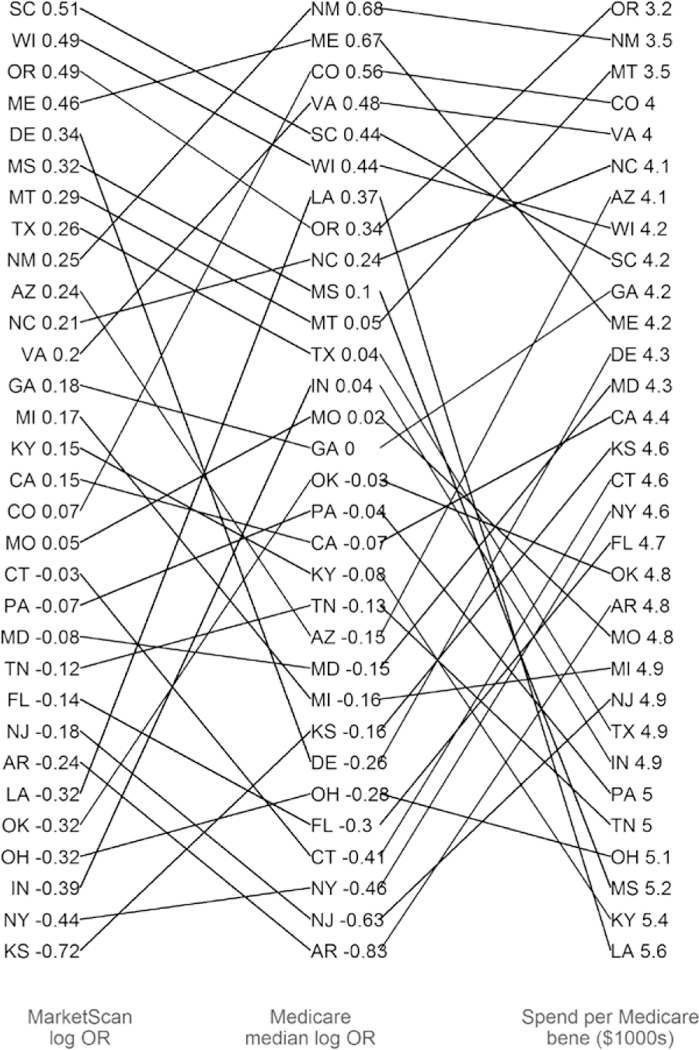

We compared this state-level analysis to other state-level measures of health care utilization. Figure 4 displays states ranked by their estimates from our previous analysis of CRT-P implant tendency at the state level among Medicare Advantage enrollees using Mar-ketScan data.5 The figure compares those state estimates and ranks to the median facility random effect in each state from the current analysis. We include only states with at least 5 facilities to estimate the median of facility-level effects in the state (current analysis) and at least 20 CRT-P implants to reliably estimate the state parameter (previous analysis). The state-level summaries were not very consistent across the 2 analyses; the correlation between the 2 sets of state summaries of CRT-P implant tendency was 0.54.

Figure 4.

Estimated state-level tendency (log odds ratio of cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker [CRT-P] versus defibrillator [CRT-D], relative to national average) from analyses of MarketScan and Medicare data.

We also compared these state estimates to state-level spending per Medicare beneficiary (adjusted for age, sex, race, and price) and found the same lack of a strong relationship in the state rankings. This indicates that geographic variation in these services is not consistent across populations with different insurance coverage (Medicare fee-for-service versus Medicare Advantage) and may be more driven by the facilities in each state than geography per se.

Associations Between Device Type and Outcomes

Comparing the unadjusted outcomes of patients receiving CRT-P and CRT-D devices illustrates the impact of the older age and greater comorbidity burden of CRT-P recipients and the more severe heart failure and more intensive treatment course of CRT-D recipients (Figure 5, right). As expected based on a presumption that more frail patients would receive CRT-P, patients who received CRT-P devices were much more likely to die within a year of implantation (12% versus 8%) and to be discharged to a skilled nursing facility following inpatient implants (8% versus 4%). However, CRT-D recipients were more likely to be readmitted for heart failure (15% versus 13%) and to have device-related reoperations (7% versus 5%). Thus, it seems that CRT-P recipients were in poorer health (higher mortality and discharge to postacute care) but had less heart failure-related care (fewer heart failure admissions and reoperations). Rates of all-cause admission (44% in CRT-D and 44% in CRT-P) and nontraumatic hip fractures (0.4% in CRT-D and 0.7% in CRT-P) were no different.

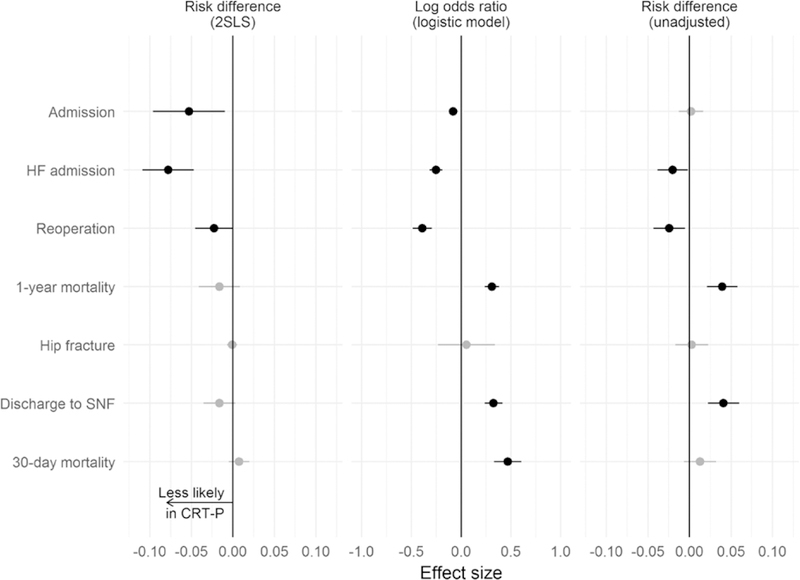

Figure 5. Adjusted and unadjusted differences in outcomes among recipients of cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker (CRT-P) versus cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) devices.

Negative values indicate lower risk of each outcome among CRT-P recipients. Intervals that exclude 0 are plotted in black. Unadjusted outcomes are shown in the right column. The middle column shows results of adjustment for patient characteristics, after which falsification end points (discharge to skilled nursing facility [SNF] and 30-day mortality) remained significantly different. Thus, the left column demonstrates the impact of including facility tendency as an instrumental variable in the model, which balances falsification end points as shown. HF indicates heart failure; and 2SRI, 2-stage residual inclusion.

After adjustment using logistic regression for patient characteristics (Figure 5, middle), the pattern of outcome differences was largely similar except that all-cause admission was now less likely among CRT-P recipients, and mortality at 30 days was more likely among CRT-P recipients. As in the unadjusted comparison, we observed more heart failure-related care and reoperations for CRT-D recipients and higher mortality and postacute care for CRT-P recipients. However, residual differences in discharge to skilled nursing facility and 30-day mortality suggest that the adjustment for patient characteristics was not sufficient to address confounding because of CRT-P recipients being in poorer health.

Thus, we turned to the IV analysis designed to address this unobserved confounding. The first-stage model predicted device receipt using patient characteristics and facility-level tendency to implant CRT-P versus CRT-D. The log odds of receiving CRT-P were 1.4 higher at a facility with significantly higher than average CRT-P tendency. This was the second-largest effect, following age 85 and older (1.62 greater log odds than age 75–80). The (McFadden’s) R2 for the model is 0.24, indicating reasonably good explanatory power for device choice. Table in the Appendix illustrates that patient characteristics were well balanced after this stage of analysis.

The second-stage model produced estimates of the effect of receiving CRT-P (versus CRT-D) on outcomes (Figure 5, left). As in the logistic model, the risk of admission (both heart failure-specific and all-cause) and reoperation was lower in recipients of CRT-P (versus CRT-D) devices.

However, the result for 1-year mortality reversed direction (lower in CRT-P recipients), but the CI included 0. The 3 falsification outcomes also now all had CIs that included 0, consistent with our assumption that the IV analysis successfully handled unobserved differences between CRT-P and CRT-D recipients.

DISCUSSION

This report describes the relative importance of patient characteristics and facility tendency to implant CRT- P versus CRT-D devices and leverages IV analysis to describe their comparative effectiveness among Medicare fee-for-service patients. Among 71 459 CRT recipients, we identified stark variation across facilities in CRT-P versus CRT-D utilization, not otherwise explained by measurable patient factors. We also found that, using this facility-level variation in device preference as an IV to control for residual confounding, there was no significant difference in 1-year mortality, while reoperations and hospitalizations favored patients receiving CRT-P devices. These findings suggest that CRT-P, with its lower cost, fewer complications, and similar 1-year survival outcomes, may be preferred for Medicare beneficiaries considering new CRT implantation.

Whether CRT-P versus CRT-D selection influences clinical outcomes in older patients remains a key clinical question with relatively little prior clinical data.3 The COMPANION trial (Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure) compared optimal medical therapy alone to the addition of CRT-D or CRT-P implantation in a 1:2:2 fashion among 1520 patients with New York Heart Association Class III-IV heart failure.17 Both devices reduced the combined primary end point (death or all-cause hospitalization), while only the CRT-D appeared to improve survival alone. However, the impact of defibrillator backup on survival likely depends in part on heart failure severity, patient age, and the presence of prior infarction as the cause of systolic dysfunction, as suggested by the recent Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure trial describing relatively low rates of sudden cardiac death among symptomatic systolic heart failure patients (58% receiving CRT).18 Similar results were found in a single-center cohort study of 686 CRT recipients in Belgium, with the specific focus on mode of death among octogenarians (N=178) at a mean follow-up of 38 months, with 21% of patients receiving CRT-D.19 Deaths were largely noncardiac (74%, compared with 50% among younger patients) and only 1 (3%) was due to tachyarrhythmia, compared with 11% tachyarrhythmic deaths in younger patients. From these findings, the authors concluded that CRT-D may have little practical value compared with CRT-P given the low incidence of arrhythmic death in older patients.20

Our data adds to this literature to further describe outcomes among contemporary older patients eligible for CRT. Many clinical factors that we cannot observe in claims data may affect the decision to implant CRT-P versus CRT-D. These include echocardiographic parameters, QRS morphology and duration, renal function, and more nuanced clinical details, such as frailty.20 Our logistic model, adjusting for known confounders, showed that 1-year mortality favored CRT-D recipients, but with evidence of residual confounding that is likely endemic to traditional comparative effectiveness assessments of CRT and ICDs. By contrast, we used the large variation among facilities in their use of CRT-P (versus CRT-D) devices, after controlling for patient characteristics, to construct an IV approach to estimate less-biased outcome comparisons among much larger numbers of patients than have been enrolled in clinical trials.

Using this approach, we found balanced clinical factors and no difference in falsification outcomes, which suggests more plausible control of confounding. This model showed similar 1-year mortality, lower hospitalization rates and fewer reoperations for CRT-P implants. While pivotal clinical trials of CRT21–24 were not specifically designed or powered to assess outcomes in older patients, and provide only limited evaluation of comorbid conditions, the results of our large, nationally representative study argue that at worst there is clinical equipoise between CRT-P and CRT-D among Medicare beneficiaries, and at best CRT-P may be preferred absent a compelling indication for an ICD, such as prior ventricular arrhythmia, positive EP study, or patient preference.

The need for evidence-based clarification of CRT outcomes is further anchored by the dramatic variability we identified among facilities, between states, and across insurance types that could not be readily explained by available covariates. One recent study of contemporary US CRT utilization based on claims (N=17 780) found that only 15% of implants were CRT-P, though an increase from 12% to 20% was seen from 2008 to 2013.5 Similarly, a separate analysis using only inpatient cases of CRT (2006–2012) found that 86% overall were CRT-D implants, including among those patients age >75 and those with multiple comorbidities, with substantial interhospital variability.4 At the same time, more than a third of all patients in the United States receiving ICDs also receive CRT,25 and this proportion increases to 40% among those over age 80.26 These proportions contrast with reports from Europe illustrating more reserved allocation of CRT-D systems,27 but accord with prior studies demonstrating marked variability in the use of single-versus dual-chamber ICDs in the United States.9 Our finding of >7-fold odds of receiving CRT-P when comparing the highest to lowest quartile facilities suggests a dire need for a clearer understanding of how CRT implantation decisions are made in real-world practice.

Our analysis includes potential limitations and rests on certain assumptions that require careful consideration. While billing claims have been widely used for observational research, they lack the clinical detail of registries, including laboratory and test data, as well as functional and physiological measures of heart failure cause and symptoms, such as left ventricular ejection fraction, QRS duration, and New York Heart Association class. However, the general indications for CRT implantation are consistent regardless of CRT-D versus CRT-P selection, and the variables we considered a priori to be most strongly associated with device choice (age and atrial fibrillation) were included in our models. Despite the large total sample size, it was not large enough to characterize individual physicians in terms of their tendency to implant CRT-P versus CRT-D devices with sufficient precision. We limited our outcomes ascertainment to 1 year to reduce the chances of patients transitioning out of fee-for-service to Medicare Advantage or other insurance plans. While this may partially limit the survival analysis between CRT-D and CRT-P, our large sample size (>70 000 patients, compared with 1000–2000 for typical CRT and ICD studies) should be sufficiently powered to detect the 2% to 6% annualized survival advantage typically ascribed to defibrillator treatment.28,29

An important assumption in our approach is the belief that facility tendency to implant CRT-P (estimated, as we do here, net of observable patient characteristics) is largely driven by idiosyncratic preferences of the providers rather than by factors that could influence patient health outcomes. However, possible threats to the validity of this proposed instrument do exist. One possibility is violation of the assumption that there is no direct causal relationship to outcomes except via the treatment. For the utilization outcomes, it may be that a facility preference for aggressive care or availability of local services may cause more discharge to skilled nursing facilities in particular. A second possibility is violation of the assumption that the instrument is uncorrelated with unmeasured confounders of the treatment-outcome relationship. In addition to unobservable patient preferences for aggressive care, unobserved health status is an important potential confounder. We cannot offer empirical evidence that facility tendency is uncorrelated with unobserved confounders. However, the near-zero estimates for the CRT-P effect on 30-day mortality in particular—contrasting with the strong signal for this end point seen in the logistic model—supports the assumption that the IV approach is not affected by this source of bias. Another potential limitation is our use of the 2SLS approach for the IV model. We provide an output, which was qualitatively similar, from an alternative model using residual inclusion in the Appendix.

In sum, our nationwide assessment of CRT utilization and outcomes accords with calls to apply real-world evidence to compelling clinical questions about medical devices.30 While consensus guidelines in device-based therapy historically have drawn only from randomized trials, none have yet been published specifically comparing CRT-P to CRT-D, and enrolling anything like the sample size included here would not be realistic. Efficiently randomizing even smaller numbers of patients without sacrificing generalizability would also be an important constraint on trial completion or applicability. Thus, rigorous comparative effectiveness methodology may well be the best source of evidence for comparing CRT-P to CRT-D, and at the least should provide context for clinicians and patients considering new CRT implantation, for whom productive shared decision-making rests on a reasonable understanding of likely clinical outcomes afforded by the available options.31 At the same time, prospective mixed-methods research identifying qualitative and quantitative elements of the decision-making process for CRT implantation will be needed to explain the stark variability identified here.

CONCLUSIONS

CRT-P versus CRT-D selection varies substantially among facilities, adjusted for clinical factors. While logistic regression did not seem to adequately account for confounding, after IV adjustment for clinical covari- ates and facility preference, 1-year survival did not differ between the devices, while other clinical outcomes favored CRT-P

Supplementary Material

Table.

Characteristics of the Study Sample, Separately for Patients Who Received CRT-P and CRT-D Devices

| CRT-P, N (%) |

CRT-D, N (%) |

SMD | All, N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 5285 (44) | 16 731 (28) | 0.34 | 22 016 (31) |

| Age 65–70 | 1039 (9) | 10 469 (18) | −0.265 | 11 508 (16) |

| Age 70–75 | 1889 (16) | 15 184 (26) | −0.240 | 17 073 (24) |

| Age 75–80 | 2616 (22) | 16 690 (28) | −0.141 | 19 306 (27) |

| Age 80–85 | 3152 (26) | 12 477 (21) | 0.129 | 15 629 (22) |

| Age 85+ | 3229 (27) | 4714 (8) | 0.521 | 7943 (1 1) |

| 2006 | 1229 (10) | 10 584 (18) | −0.216 | 11813 (17) |

| 2007 | 1339 (11) | 9401 (16) | −0.134 | 10 740 (15) |

| 2008 | 1472 (12) | 8518 (14) | −0.058 | 9990 (14) |

| 2009 | 1698 (14) | 8807 (15) | −0.016 | 10 505 (1 5) |

| 2010 | 2049 (17) | 8557 (14) | 0.077 | 10 606 (15) |

| 2011 | 2038 (17) | 7303 (12) | 0.137 | 9341 (13) |

| 2012 | 2100 (18) | 6364 (1 1) | 0.200 | 8464 (12) |

| Race white | 11 399 (96) | 55 145 (93) | 0.126 | 66 544 (93) |

| Race black | 346 (3) | 3403 (6) | −0.139 | 3749 (5) |

| Race Hispanic | 55 (0) | 267 (0) | 0.002 | 322 (0) |

| Race other | 118 (1) | 677 (1) | −0.014 | 795 (1) |

| Ischemic disease | 7339 (62) | 45 244 (76) | −0.316 | 52 583 (74) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 3641 (31) | 27 636 (46) | −0.331 | 31 277 (44) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7983 (67) | 23 086 (39) | 0.588 | 31 069 (43) |

| Conduction disorder | 3775 (32) | 21 845 (37) | −0.106 | 25 620 (36) |

| Arrhythmia | 3808 (32) | 15 235 (26) | 0.140 | 19 043 (27) |

| Prior HF admission | 1945 (16) | 12 194 (20) | −0.108 | 14 139 (20) |

| Cardiac arrest | 94 (1) | 1171 (2) | −0.101 | 1265 (2) |

| 3+ comorbidities | 5287 (44) | 25 842 (43) | 0.019 | 31 129 (44) |

| 2 comorbidities | 2642 (22) | 13 412 (23) | −0.009 | 16 054 (22) |

| 1 comorbidity | 2514 (21) | 11 880 (20) | 0.028 | 14 394 (20) |

| No comorbidities | 1482 (12) | 8400 (14) | −0.050 | 9882 (14) |

CRT-D indicates cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators; CRT-P, CRT- pacemaker; HF, heart failure; and SMD, standardized mean difference.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is commonly used in older patients with systolic heart failure, either with pacing only (CRT-P) or with defibrillator backup (CRT-D).

Most patients receiving new CRT systems in the United States receive CRT-D, which is more expensive and may have higher risk of complications.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

Using data from fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries (N=71 459, 2006–2012), we identified substantial variability among facilities in preference for CRT-P versus CRT-D implantation, unexplained by clinical factors.

Modeling using instrumental variable analysis suggested that there was no difference in survival between CRT-P and CRT-D recipients.

CRT-P may be preferred for Medicare beneficiaries considering new CRT implantation.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Drs Hatfield and Normand were supported by the Food and Drug Administration’s Medical Device Epidemiology Network Methodology Center (U01FD004493). Dr Kramer was supported by the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program in Bioethics.

Footnotes

The Data Supplement is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRC0UTC0MES.118.004763.

Disclosures

Dr Kramer serves as a consultant to the Baim Institute for Clinical Research on clinical trials related to medical devices (unrelated to current topic). The other authors report no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, DiMarco JP, Dunbar SB, Estes NA III, Ferguson TB Jr, Hammill SC, Karasik PE, Link MS, Marine JE, Schoenfeld MH, Shanker AJ, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Stevenson WG, Varosy PD, Ellenbogen KA, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hayes DL, Page RL, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society, [corrected]. Circulation. 2012; 126:1784–1800. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182618569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rickard J, Michtalik H, Sharma R, Berger Z, Iyoha E, Green AR, Haq N, Robinson KA. Use of Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy in the Medicare Population. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kramer DB, Reynolds MR, Mitchell SL. Resynchronization: considering device-based cardiac therapy in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:615–621. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindvall C, Chatterjee NA, Chang Y, Chernack B, Jackson VA, Singh JP, Metlay JP. National trends in the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy with or without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circulation. 2016;133:273–281. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatfield LA, Kramer DB, Volya R, Reynolds MR, Normand SL. Geographic and temporal variation in cardiac implanted electric devices to treat heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003532. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torbica A, Banks H, Valzania C, Boriani G, Fattore G. Investigating regional variation of cardiac implantable electrical device implant rates in European healthcare systems: what drives differences? Health Econ. 2017;26(suppl 1):30–45. doi: 10.1002/hec.3470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ovsyshcher IE, Furman S. Determinants of geographic variations in pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators implantation rates. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26(1 pt 2):474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groeneveld PW, Heidenreich PA, Garber AM. Trends in implantable cardio-verter-defibrillator racial disparity: the importance of geography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matlock DD, Peterson PN, Wang Y, Curtis JP, Reynolds MR, Varosy PD, Masoudi FA. Variation in use of dual-chamber implantable car- dioverter-defibrillators: results from the national cardiovascular data registry. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:634–641; discussion 641. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khera R, Angraal S, Couch T, Welsh JW, Nallamothu BK, Girotra S, Chan PS, Krumholz HM. Adherence to methodological standards in research using the national inpatient sample. JAMA. 2017;318:2011–2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brookhart MA, Rassen JA, Schneeweiss S. Instrumental variable methods in comparative safety and effectiveness research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:537–554. doi: 10.1002/pds.1908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Setoguchi S, Warner Stevenson L, Stewart GC, Bhatt DL, Epstein AE, Desai M, Williams LA, Chen CY. Influence of healthy candidate bias in assessing clinical effectiveness for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: cohort study of older patients with heart failure. BMJ. 2014;348:g2866. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Athey S, Imbens GW. The state of applied econometrics: causality and policy evaluation. J Econ Perspect. 2017;31:3–32.29465214 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh RW, Vasaiwala S, Forman DE, Silbaugh TS, Zelevinski K, Lovett A, Normand SL, Mauri L. Instrumental variable analysis to compare effectiveness of stents in the extremely elderly. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:118–124. doi: 10.1161/CIRC0UTC0MES.113.000476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wimmer NJ, Secemsky EA, Mauri L, Roe MT, Saha-Chaudhuri P, Dai D, McCabe JM, Resnic FS, Gurm HS, Yeh RW. Effectiveness of arterial closure devices for preventing complications with percutaneous coronary intervention: an instrumental variable analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTI0NS.115.003464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Secemsky EA, Kirtane A, Bangalore S, Jovin IS, Patel D, Ferro EG, Wimmer NJ, Roe M, Dai D, Mauri L, Yeh RW. Practice patterns and in-hospital outcomes associated with bivalirudin use among patients with non-ST- segment-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e003741. doi: 10.1161/CIRC0UTC0MES.117.003741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, Carson P, DiCarlo L, DeMets D, White BG, DeVries DW, Feldman AM; Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (C0MPANI0N) Investigators. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Køber L, Thune JJ, Nielsen JC, Haarbo J, Videb^ k L, Korup E, Jensen G, Hildebrandt P, Steffensen FH, Bruun NE, Eiskjær H, Brandes A, Thøgersen AM, Gustafsson F, Egstrup K, Videbæk R, Hassager C, Svendsen JH, Høf- sten DE, Torp-Pedersen C, Pehrson S; DANISH Investigators. Defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1221–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martens P, Verbrugge FH, Nijst P, Dupont M, Mullens W. Mode of death in octogenarians treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Card Fail. 2016;22:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer DB, Steinhaus DA. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in older patients: age is just a number, and yet .... J Card Fail. 2016;22:978–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L; Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) Study Investigators. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang AS, Wells GA, Talajic M, Arnold M0, Sheldon R, Connolly S, Hohnloser SH, Nichol G, Birnie DH, Sapp JL, Yee R, Healey JS, Rouleau JL; Resynchronization-Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial Investigators. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild- to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Klein H, Brown MW, Daubert JP, Estes NA III, Foster E, Greenberg H, Higgins SL, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD, Wilber D, Zareba W; MADIT-CRT Trial Investigators. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1329–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linde C, Abraham WT, Gold MR, St John Sutton M, Ghio S, Daubert C; REVERSE (Resynchronization Reverses Remodeling in Systolic Left Ventricular Dysfunction) Study Group. Randomized trial of cardiac resynchronization in mildly symptomatic heart failure patients and in asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction and previous heart failure symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1834–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein AE, Kay GN, Plumb VJ, McElderry HT, Doppalapudi H, Yamada T, Shafiroff J, Syed ZA, Shkurovich S; ACT Investigators. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator prescription in the elderly. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1136–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kremers MS, Hammill SC, Berul CI, Koutras C, Curtis JS, Wang Y, Beachy J, Blum Meisnere L, Conyers del M, Reynolds MR, Heidenreich PA, Al-Khatib SM, Pina IL, Blake K, Norine Walsh M, Wilkoff BL, Shalaby A, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld J. The national ICD registry report: version 2.1 including leads and pediatrics for years 2010 and 2011. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:e59–e65. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raatikainen MJ, Arnar D0, Merkely B, Camm AJ, Hindricks G Access to and clinical use of cardiac implantable electronic devices and interventional electrophysiological procedures in the European Society of Cardiology Countries: 2016 Report from the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2016;18 (suppl 3):iii1-iii79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH; Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Investigators. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:225–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML; Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Resnic FS, Matheny ME. Medical devices in the real world. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:595–597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1712001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kramer DB, Brock DW, Tedrow UB. Informed consent in cardiac resynchronization therapy: what should be said? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:573–577. doi: 10.1161/CIRC0UTC0MES.111.961680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.