Abstract

The purpose of this article was to review the current literature on psychosocial implications of Marfan syndrome (MFS) and its impact on adolescents, adults, their families and to provide important considerations for providers. Since the previous reviews in 2015, numerous studies have been published that are included in the current review. This literature review was conducted using PubMed, Medline, PsychINFO, ERIC, Web of Science, and Academic Search Premier databases and only articles that studied psychosocial factors that influence MFS patients as adolescents, adults, family members, or their interactions with providers were included in this review. Of the 522 articles reviewed, 41 were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All articles were peer-reviewed. MFS has various implications that can impact one's life; studies have shown that MFS causes a negative impact on an individual's formative years, quality of life, reproductive decision-making, work participation, and satisfaction with life. Clinicians and multidisciplinary teams should be aware of these factors to provide support focusing on coping strategies for the patient and their family.

Keywords: Marfan syndrome, quality of life, chronic pain, psychosocial factors, coping, caregivers

Introduction

Marfan syndrome (MFS) is an autosomal dominant connective tissue disorder that affects multiple organs including the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and ocular systems with a prevalence of approximately 1 in every 5,000 live births. 1 2 Secondary manifestations of MFS may also impact the skin, pulmonary, and nervous systems. 3 Aortic dilation can lead to aortic dissection, which is a life-threating condition. 1 Thus, most patients are closely monitored from childhood for serial assessment of the aorta, especially the aortic root. Since introduction of prophylactic aortic root surgery, their life expectancy has improved. 4

As MFS is a pleotropic disease (i.e., one mutation can cause multiple traits), not all patients present with the same symptoms or phenotypic presentation. Therefore, the experience of the disease will be unique to the individual and subject to psychosocial manifestations from the symptoms of the disease. Psychosocial factors can be described as the impact of social factors that influence an individual's mind or behavior. 5 Studies indicate that patients across all age groups can experience distress related to their physical characteristics of MFS. 6 7 This distress can impact a patient's overall health and experience, especially during their formative years. 1 8 9 Other studies have indicated a possible relationship between fatigue and chronic pain for individuals with MFS. 10 In addition, some MFS patients also have psychiatric symptoms such as depression and anxiety. 6 11 As with many genetic disorders, patients with MFS also have concerns with various aspects of life, such as family planning and finances related to health care. 12 Not surprisingly, caregivers of individuals with MFS report that financial instability is one of their largest stressors. 13 The combination of all these factors can lead to a diminished quality of life (QoL). 9 12

A few review studies on the psychosocial factors, chronic pain, and psychiatric manifestations of MFS have been published recently and many of our findings concur with theirs. 14 15 16 Since these three reviews, there have been an additional sixteen publications on various aspects of the psychosocial factors of MFS that add to the robustness of this topic that we identify in this manuscript. 11 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Many of these additional publications are noted in a fourth review that was recently conducted by Velvin et al and focused on the QoL of individuals with hereditary thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection diagnoses including MFS. 32

The purpose of this article was to review the current literature on psychosocial implications of MFS and other contributing factors that affect children and adolescents, adults, and their families. We aim to elaborate on previous published articles and provide a unique perspective regarding the relationship that family and caregivers have with MFS patients. We reviewed the literature and identified common themes that characterize concerns of patients with MFS and their families. Our goal is to raise awareness of the psychosocial implications and contributing factors of MFS at various life stages that may impact MFS patients, their families, and providers. This article will address the psychosocial aspects of MFS as well as identifying areas lacking in substantial research that could further our understanding and enhance possible treatments and protocols.

Methods

Study Design

A literature review was conducted according to the basis of guidelines in the established literature. 33 34 Because there are limited studies on MFS and its effects on psychosocial aspects, both qualitative and quantitative studies were included in this review. Common themes from the studies were identified via thematic analysis. 35

Literature Search

Article searches were conducted from 1989 to May 2019. Searches were conducted using PubMed, Medline, PsychINFO, ERIC, Web of Science, and Academic Search Premier databases searching for literature using the following search terms: Marfan syndrome and pain, family life, living, psychiatry, quality of life, psychosocial, or fatigue. Search terms were selected after reading prior studies. References were compared with previous reviews to maintain similar sources and highlight which articles are different.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies that focused on treatment or interventions on MFS were excluded except when the study specifically included psychosocial aspects of MFS. Studies that included other genetic connective tissue disorders or genetic cardiac disorders were excluded unless the studies included a sample of MFS patients. Conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries, correspondence, case reports, and case studies were excluded from this review. Articles published before 1989 were also excluded from the review.

The inclusion criteria consisted of articles that discussed the psychosocial aspects of MFS, related to either the individual with MFS or their families. Additionally, studies addressing living with MFS, quality of life, psychological distress, social adjustment, pain, fatigue, coping with MFS-specific symptoms, and overall physical and mental health of MFS were also included in this review. All age, gender, and ethnic groups of MFS patients were included in this study. Only peer-reviewed articles that have been published in English were included.

Screening Process

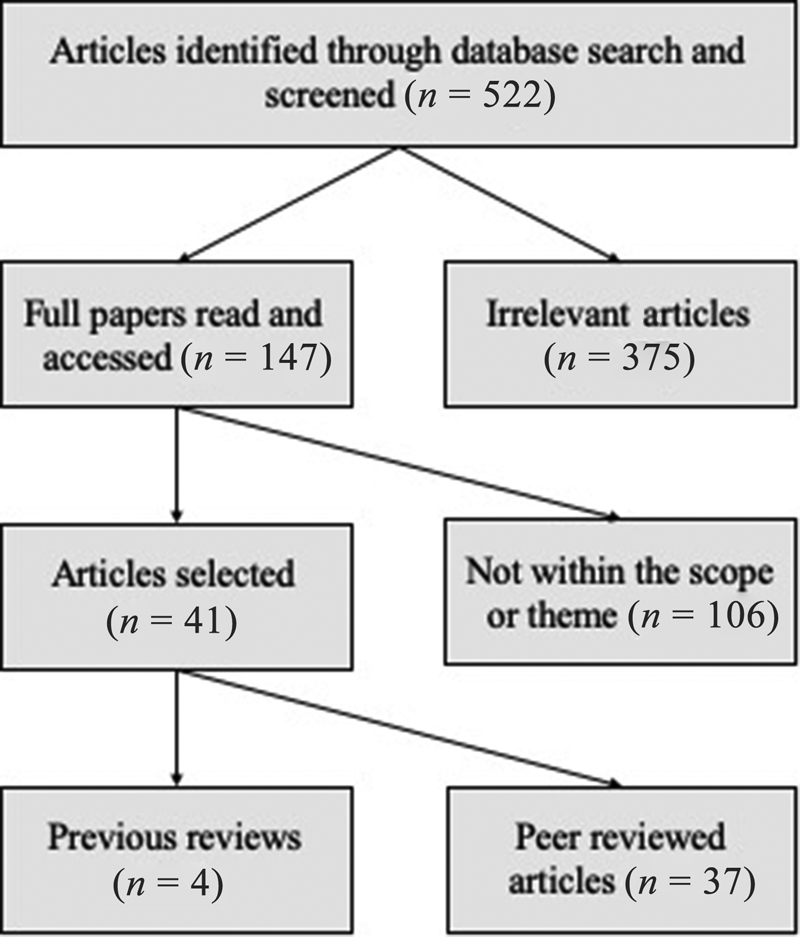

Fig. 1 provides a visual representation of the article screening process. The specific search criteria found 522 articles after duplicate articles were removed. These 522 articles were saved into EndNote X9. Of these 522 articles, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance to MFS. Case reports and case studies were excluded. If the title/abstract did not provide enough information to determine if it was to be excluded during this phase, the full article was retrieved. A total of 375 articles were excluded at this time based on exclusion criteria. At this point, 147 articles were collected and read by author C.N. Articles were further screened by the aforementioned inclusion criteria. After reading each article, a total of 41 articles were selected to be part of this review including four review studies. Table 1 lists the articles which were selected for this review.

Fig. 1.

Selection process . A total of 522 articles were identified through database search and were screened. One hundred forty-seven were articles read and accessed for eligibility to be in the review. One hundred fourteen did not fit the scope or theme of this review. Forty-one articles were selected; of which four were review articles and 37 were peer-reviewed articles.

Table 1. Selected articles.

| Author (Year) | N | Main findings |

|---|---|---|

| Handisides et al 18 (2019) | 321 | Children (5–18 y) with MFS scored lower than healthy population norms for physical and psychosocial domains of quality of life. |

| Stanišić et al 27 (2018) | 16 | MFS patients had higher than average satisfaction with life. |

| Treasure et al 28 (2018) | 119 MFS patients, 25 physicians | An active lifestyle was reported to be more important in male MFS patients, compared with female MFS patients. Patients placed more importance than doctors on not deferring surgery and on avoidance of anticoagulation in the interests of childbearing. |

| Ratiu et al 20 (2018) | 318 | Executive function difficulties and metal fatigue are associated with MFS symptoms and affect quality of life. |

| Speed et al 19 (2016) | 245 | 89% of respondents with MFS reported having pain while 28% of individuals reported pain as their presenting symptom of MFS. |

| Goldfinger et al 22 (2017) | 389 | College education, marital status, higher household income, private health insurance, full-time employment, moderate alcohol use, fewer prior surgeries, fewer comorbid conditions, absence of depression, and less severe MFS manifestations were all reported as positive predictors of quality of life in MFS patients. |

| Benninghoven et al 25 (2017) | 18 | MFS patients were highly satisfied with the inpatient rehabilitation program and resulted in significant positive changes for mental health, fatigue, nociception and vitality domains for quality of life. |

| Benke et al 11 (2017) | 45 | MFS patients experience increased trait anxiety compared with healthy individuals after acute life-saving surgery. |

| Velvin et al 49 (2016) | 73 | Adults with MFS experienced decreased satisfaction with life compared with the general Norwegian population. Only fatigue, aortic dissection, and having regular contact with psychologist showed significant effect on satisfaction with life. |

| Rao et al 21 (2016) | 230 | Across all quality of life domains, MFS patients scored significantly lower than United States population norms. |

| Mueller et al 17 (2016) | 42 | No significant overall reduction of quality of life was found in MFS patients from (4–18 y) of age. |

| Moon et al 23 (2016) | 218 | In patients with MFS, the quality of life was affected significantly by social support, disease-related factors, and biobehavioral factors, such as anxiety and depression. |

| Ghanta et al 24 (2016) | 49 | After life-saving aortic surgery, MFS patients reported slightly worse physical scores with slightly better mental scores than the general population. |

| Nelson et al 48 (2015) | 993 | 67% of MFS participants reported pain in the preceding 7 days. 56% of participants noted analgesic use to control pain related to MFS with 55% reporting <50% pain relief. |

| Velvin et al 57 (2015) | 70 | 59% of participants were employed or students, significantly lower work participation than the general Norwegian population. Age, lower educational level, and severe fatigue were significantly associated with low work participation; not MFS related health problems or chronic pain. |

| Kelleher et al 29 (2015) | 147 posts | Social media content related to MFS can identify various common emotions, such as anxiety and depression |

| Bathen et al 10 (2014) | 72 | Participants reported significantly higher prevalence of severe fatigue compared with the general Norwegian population and patients with rheumatoid arthritis, but lower than in other chronic conditions. |

| Johansen et al 26 (2013) | 11 children, 10 Caregivers | MFS was found to have a negative impact on the quality of life in these children, however, there was no impact identified in their caregiver's satisfaction with life. |

| Song et al 30 (2013) | 194 | MFS patients who had undergone emergent aortic surgery had a significantly lower quality of life. |

| Schoormans et al 31 (2012) | 121 | MFS patients' quality of life score was significantly lower in the physical domain which was weakly related to age and presence of scoliosis. |

| Rand-Hendriksen et al 55 (2010) | 84 | MFS patients, compared with the general population, demonstrated lower quality of life domains for social function, vitality, general health, bodily pain, and role physical. |

| Giarelli et al 80 (2010) | 37 | The frequency and range of self-monitoring increased with the age of the child with MFS. |

| Giarelli et al 38 (2008) A | 39 parents 37 adolescents (14–21y), 16 young adults (22–34y), health care professionals 15 |

Obstacles to transition self-management for MFS patients can believe related to three categories; person with MFS, parents, and healthcare professionals. |

| Giarelli et al 13 (2008) B | 39 parents 37 adolescents (14–21y), 16 young adults (22–34y), health care professionals 15 |

Caregivers of individuals with MFS reported that the financial concerns with one of their largest stressors. MFS adolescents were all involved in daily self-monitoring. The parent's fears and need to stay involved in the child's health care slowed the child's independent work on self-management responsibilities. |

| Van Dijk et al 52 (2008) | 59 | MFS patients reported fatigue which was significantly correlated with low orthostatic tolerance. There was no relationship between β-blocker use and fatigue. |

| Fusar-Poli et al 9 (2008) | 36 | MFS patients reported an impaired health-related quality of life in the psychological domain but not in the physical domain. Being male and older was significantly associated with a poorer perceived mental quality of life. |

| Percheron et al 50 (2007) | 21 | MFS patients had significantly higher fatigue than the controls. |

| Rand-Hendriksen et al 51 (2007) | 16 | Self-reported fatigue was comparable with fatigue reported in other severe chronic diseases and disabilities and was primarily in the mental/psychological domain. Psychological distress was higher than expected compared with the population at large. |

| Peters et al 40 (2005) | 174 | Fifty-six respondents (32%) reported feeling discriminated against or socially devalued because of having MFS. Endorsement of discrimination was significantly correlated with having depressive symptoms, low self-esteem, the view MFS has had significant negative consequences on one's life, striae, and perceptions of workplace discrimination. Instances of workplace discrimination were perceived by 20% of respondents, and 23% reported that they remained in a dissatisfying job due to having MFS. |

| Foran et al 53 (2005) | 22 | Symptoms associated with dural ectasia had a marked impact on the overall health of patients with MFS. |

| De Bie et al 57 (2004) | 857 | 61% of those who scored on the physical severity score as severely affected were designated as being mildly-moderately affected on subjective scoring. Two hundred-twenty women have carried 430 pregnancies (1.95 pregnancies/woman), with cardiovascular complications in 1.6%. A positive general self-image was reported by 91.5% of patients. However, more than 90% stated that MFS had a negative influence on their sexual relationships, which they ascribed to negative perception of their body image. |

| Peters et al 12 (2002) | 174 | Approximately 62% of the patients agreed that having MFS significantly affected their reproductive decision-making. 69% of MFS patients in the study reported personal interest in prenatal testing for MFS. Age, striae, back pain, and low quality of life were each independently correlated with lack of sex drive. |

| Verbraecken et al 56 (2001) | 15 | Health related quality of life scores were significantly lower in MFS patients compared with healthy controls, except for emotional problems. Sleep apnea was significantly increased in MFS patients compared with controls. |

| Peters et al 6 (2001) | 174 | The presence of cardiovascular symptoms and fatigue were positively correlated with medication use (β-blocker and calcium channel blocker) in MFS patients. |

| Peters et al 6 (2001) | 174 | 83% of the respondents perceived MFS as having had significant adverse consequences on their lives. Having striae, pain (sore joints), and depression were each independently correlated with this view. |

| Van Tongerloo et al 8 (1998) | 17 | During childhood, most MFS patients were insensitively teased by peers because of their typical phenotypic features. In female MFS patients, the risk associated with child bearing represented a major concern. |

| Schneider et al 7 (1990) | 22 | MFS patients perceived that their lives would be significantly better without MFS, especially in the areas of physical activities and self-image. Their medication compliance was suboptimal, similar to prior publications on description of compliance among teenagers with other chronic illnesses. |

| Reviews | ||

| Velvin et al 32 (2019) | N/A | |

| Velvin et al 49 (2016) | N/A | |

| Velvin et al 57 (2015) | N/A | |

| Gritti et al 16 (2015) | N/A |

Abbreviation: MFS, Marfan syndrome.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis was conducted on the selected articles to synthesize the data from both quantitative and qualitative studies, based on published guidelines. 35 36 37 Themes were identified by placing information acquired by population of participants in the articles reviewed; children and adolescents with MFS, adults with MFS, caregivers of individuals with MFS, and healthcare providers of patients with MFS. Microsoft Excel was utilized to organize and store themed data. The content in each theme was further refined and specified to determine subheadings of each section.

Results

The current review includes 16 publications on various aspects of the psychosocial factors of MFS that have been published since the aforementioned systematic reviews. 11 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Handisides et al, Johansen et al, and Mueller et al address QoL in children and adolescents. 17 18 26 Kelleher et al examined social media postings and identified common themes and topics posted along with MFS. 29 Speed et al examined pain in individuals with MFS. 19 Ratiu et al, Goldfinger et al, Rao et al, Schoormans et al, and Moon et al address the QoL in adults with MFS. 20 21 22 23 31 Benke et al, Song et al, and Ghanta et al examined the impact of surgery on MFS. 11 24 30 Stanišić et al address satisfaction with life and coping. 27 Treasure et al address the concerns of preserving QoL for MFS patients and its role in treatment decisions. 28 Lastly, Benninhoven et al found that rehabilitation programs for individuals with MFS can make a significant impact in their QoL. 25

Children and Adolescents

Social Interaction

Of the literature addressing children and adolescents, four articles mentioned social interaction as an important component of growing up with MFS. 7 8 13 38 An individual's ability to participate in social activities helps establish a sense of self and leads to the development of personal identity, starting in their formative years leading well into adulthood. 39 Schneider et al (1990) reported that adolescent MFS patients experience more difficulty fitting in with peers, dating, and believed that they would be more physically attractive without the disease. 7 Further, due to physical activity restrictions and some orthopedic limitations, these patients reported difficulty fitting in and participating in team sports during their formative years. 7 Van Tongerloo et al (1998) showed that 53% of the 17 MFS adolescents reported low self-esteem because of their physical appearance. 8 Of note, skin striae has been shown in adult populations to have a significant impact on negative views of appearance although it has not been studied in younger populations but likely has an impact as well. 40 Some MFS patients report that they do not follow the physical activity restriction recommendations, potentially to fit in better within their peer groups. 8 Further Giarelli et al found that embarrassment from being different and having a lack of peer support are possible social obstacles that could impede the transition to self-management. 38 Further research is needed to determine whether phenotypic manifestations impact transition from adolescence to adult care. These several challenges at school can ultimately lead to lower self-esteem during formative years.

In recent years, due to advancements in scientific research and the increased use of the internet, information on MFS has become more widely available. A recent study looked at both the positive and negative experiences related to MFS by reviewing posts from MFS patients on social media sites. Kelleher et al reported fatigue and depression as common symptoms discussed on social media by MFS patients. 29 This data can be useful in raising awareness for clinicians caring for these patients and facilitate appropriate adjustment of patient care. The use of social media can also help provide unity in the community and may help individuals become more comfortable sharing their experiences with MFS, creating a safe environment for encouragement and support. 29 Additionally, online self-management programs could be established for chronic genetic disorders like MFS to aid adolescents accept their condition and become more autonomous in their treatment. 13

Quality of Life

Of the literature addressing children and adolescents with MFS, three articles evaluated QoL. 17 18 26 QoL has been defined as a concept containing multiple domains that include physical, psychological, social, and existential dimension and well-being. 41 Living with a chronic illness can have an impact on one's ability to carry out daily life activities, therefore impacts QoL. Studies examining QoL have used different validated measurements and terminology. In this study, we used the term QoL and categorize other similar terms, such as “well-being,” “satisfaction with life” (SWL), and “health-related quality of life” (HRQoL) under the overarching theme of QoL. 42 43 44 A similar concept of combining terms of QoL was also utilized in the Velvin et al. 32 In this study, the authors focus on QoL and all age groups with hereditary thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection diagnoses. 32 The studies reviewed here used validated measurements to quantify QoL in the pediatric populations; either using the KINDL-R questionnaire or pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL) 4.0. 17 18 26

Studies examining QoL in young patients with MFS have found mixed results. Mueller et al conducted a study of 42 MFS adolescents, using the KINDL-R questionnaire, and found no significant overall reduction of QoL. 17 Additionally, they found that despite their distinctive phenotype, their QoL was unimpaired. It should be noted that in this study that patients diagnosed at 4 to 7 years had the same QoL scores as control participants; however, QoL scores were significantly higher for patients aged 8 to 16 years when compared with controls. 17

Johansen et al examined QoL of children in multiple different chronic illnesses, including MFS using PedsQL 4.0. 26 Although they had a small sample ( N = 11) of children and adolescents, they found that there was a significant negative impact of MFS on QoL in the domains of physical functioning, social functioning, and school functioning. However, there was no significant difference between those with MFS and controls in the domain of emotional functioning.

Handisides et al conducted a large-scale study on QoL in a sample of 321 children and adolescents with MFS, using the PedsQL. 18 They found that participants reported lower overall QoL in physical and psychosocial domains compared with healthy participants in children aged 5 to 18 years. 18 As one's formative years are associated with concern of body image, psychosocial QoL will be affected by chronic genetic disorders like MFS that have an effect on their phenotypic presentation. These results are more consistent with findings about QoL in the adult MFS population. Interestingly, Handisides et al also found that young adults with MFS had significant impairment in physical QoL, but had significantly greater total and psychosocial QoL compared with healthy participants. 18 Handisides et al noted a possible explanation for this finding is that young adults may have developed better coping skills. 18 Another possible explanation for their finding is that individuals in this age group who had aortic surgery were excluded from the data, which could exclude MFS individuals with lower QoL. As a side note, Handisides et al found that males more often reported negative psychosocial QoL compared with females. 18 Additional research using validated measurements for QoL in both children and adolescents can help shape the narrative and improve our understanding of areas that can be targeted for intervention. Although further research is required to determine the exact factors impacting the changes in QoL, individuals who are suffering from their body image may benefit from treatments designed to improve the other QoL domains. 45 46

Adults

Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Of the literature reviewed and categorized into the adults' theme, 13 articles examined the effects of pain and fatigue in MFS. 6 10 15 19 21 22 25 47 48 49 50 51 52 In the Velvin et al review of chronic pain, 18 articles were found and the review demonstrated that the prevalence of pain in MFS ranges widely from 47 to 92% and chronic pain limits daily function. 15 21 22 25 49 Four articles have been published since this review addressing pain. 19 21 22 25 More recently, Speed et al demonstrated that adult MFS patients experience pain with a prevalence of 89%. 19 Benninghoven et al studied the effects of rehabilitation in their MFS population and how it had an impact on minimizing the patient population's pain. 25 Rao et al noted that the most severe type of pain their respondents experienced was back pain followed by neck pain and headaches. 21 They also found that women with MFS experienced more severe headaches than men. 21 Dural ectasia, a characteristic of MFS, is associated with lower back pain, headache, and muscle weakness. 53 Dural ectasia, degenerative disk disease, kyphosis and, early osteoarthritis are noted to influence greater pain severity compared with MFS patients without these conditions. 51

There have been relatively few studies that describe treatment options for pain. Nelson et al noted that less than half of their respondents who use frequent analgesics have low treatment efficacy with analgesics and very few have utilized interventional procedures for pain. 48 Additionally, less than half of these respondents reported being “satisfied” with their current pain treatment. Speed et al noted that 41% of their respondents had not received a pain diagnosis. 19 Mismanagement of pain due to MFS could affect patients negatively. Although chronic pain in MFS has not been associated with reduced satisfaction with life, it can cause physical disability and an increased psychological burden. 19 Goldfinger et al argue that those who were unable to work due to chronic pain may belong to a category of more severe MFS manifestations. 22

Chronic pain of MFS has been found to be associated with fatigue, which has been a major complaint of individuals with MFS. 10 21 47 50 Bathen et al stated that MFS adults reported a higher prevalence of severe fatigue compared with the general Norwegian population and rheumatoid arthritis but did not significantly differ from other chronic disease populations. 10 Benninghoven et al found similar levels of fatigue in their prerehabilitation MFS population. 25 Patients with MFS who experience higher levels of fatigue report lower satisfaction with life. 49 Rao et al noted that fatigue was ranked as the third highest concern where cardiac and spine problems were ranked first and second, respectively. 21 Additionally, fatigue has been associated with diminished cognitive functioning, and the perception that MFS is a lethal condition. 6 Findings regarding fatigue in the MFS population are somewhat inconsistent. For example, Rand-Hendriksen et al noted in their study that MFS participants had a similar amount of fatigue compared with other severe chronic diseases. 51 However, Percheron et al did not observe a difference in objective muscle fatigue in MFS women when compared with controls. 50

Findings regarding pain and medication use are also mixed. Peters et al found that fatigue was positively correlated with medication use such as β-blocker and calcium channel blockers, while Rand-Hendriksen et al found no significant relationship between fatigue and β-blocker use in their study. 47 51 Van Dijk et al noted in their study that there was no significant relationship between fatigue and β-blocker use but did note a significant relationship between fatigue and orthostatic intolerance. 52 Bathen et al argued that further research is needed to examine the association between fatigue and blood pressure medications, like β-blockers, in MFS as there is conflicting data in the literature. 10 With regards to sex differences, fatigue was reported more in women suffering from MFS. 6 47 Rand-Hendriksen et al noted significantly higher amount of mental fatigue in MFS women. 51 However, it may be difficult to distinguish fatigue related to the disorder compared with fatigue related to treatment of MFS.

Further research is needed to determine the exact etiology of the pain and fatigue experienced by those with MFS, which could categorize features of MFS and their possible associations with fatigue and pain. Using treatment to control the symptoms of pain could improve individual's daily life. Focusing treatment and other management options that improve fatigue could potentially improve satisfaction with life and work participation. Further, clinicians need to be aware of not only the cardinal features of MFS but also consider these overlapping features that play a role in decreased satisfaction with life.

Factors that Impact Quality of Life

Of the literature reviewed and categorized into the adults theme, 23 articles evaluated either QoL directly or factors that impact QoL such as employment in adults. 9 11 12 14 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 27 28 30 31 32 40 49 53 54 55 56 57 Velvin et al and Velvin et al are two reviews that focus on QoL. 14 32 Stanišić et al, Velvin et al, Benke et al used the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). 11 27 49 Verbraecken et al, Foran et al, Fusar-Poli et al, Rand-Hendriksen et al, Song et al, Schoormans et al, Moon et al, Rao et al , Benninghoven et al, and Goldfinger et al all utilized the short form medical survey (SF-36) to quantify health-related quality of life (HRQOL) while Speed et al and Ghanta et al used short form medical survey (SF-12). 9 19 21 22 23 24 25 30 31 53 54 55 Peters et al utilized the Ferrans' and Powers' Quality of Life Index, cardiac version (QLI, cardiac III), and Ratiu et al used the Ferrans' Quality of Life Index (QLI). 12 20

Having a diagnosis of MFS alone will likely impact QoL. Velvin et al noted adults with MFS experienced decreased satisfaction with life compared with the general Norwegian population and found fatigue and aortic dissection negatively impacted satisfaction with life. 49 In contrast, Stanišić et al found that MFS patients had a higher than average satisfaction with life; however, they had a small sample ( N = 12). 27 Treasure et al found that men with MFS are particularly interested in having an active lifestyle. 28 These authors argue that patients may prefer the option of valve sparing aortic surgery and clinicians should take these preference into account as it may influence their satisfaction with life. 28 Further, Rao et al (2016) found that QoL was lower in all domains compared with the U.S. general population. 21 Goldfinger et al utilized the genetically triggered thoracic aortic aneurysms and cardiovascular conditions (GenTAC) registry participants and studied 389 adult MFS patients and demonstrated that QoL was lower than the general population average. 22 They found that predictors of better QoL were having college education, marital status, higher household income, private health insurance, and full-time employment. 22 Additionally, they demonstrated that having fewer surgeries, fewer comorbid conditions, absence of depression, and less severe manifestations of MFS were also associated with higher levels of QoL. 22 Moon et al found that depression, anxiety, fatigue, pain, and body were biobehavior variables that affect QoL. 23 Peters et al and Fusar-Poli et al demonstrated that the psychosocial subcategory of QoL was lower compared with a population with cardiovascular disease and the Italian general population, respectively. 9 12 Ratiu et al demonstrated that patients with MFS may experience specific difficulties in executive function, such as mental fatigue leading to diminished QoL. 20 Other studies identified several factors related to QoL in individuals with MFS, such as pain, employment, feelings of discrimination, and self-image. 40 53 57

A primary contributor to decreased QoL in individuals with MFS is pain, which is unsurprising given the findings related to pain in individuals with MFS. Rand-Hendriksen et al (2010) found that in the physical domain of QoL, patients with MFS report bodily pain at much higher rates than other chronic illness groups. 54 Foran et al studied the MFS feature dural ectasia and its association with pain, which could be contributing to the decrease in QoL. 53

Physical symptoms also impact QoL. Schoormans et al demonstrated in their study that physical QoL was diminished compared with the general population and was correlated with age and scoliosis. 31 Song et al demonstrated that individuals with MFS who underwent emergency surgery had lower QoL compared with those who had elective surgery. 30 In a study conducted by Ghanta et al, 24 patients with MFS who had undergone thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair were evaluated for QoL and reported slightly worse physical scores with slightly better mental scores compared with general population. 24

The impact of chronic illness on one's ability to work and build a career could influence overall QoL, illustrating the importance of this information in describing the psychosocial implications of MFS. Employment is associated with higher self-esteem and higher life satisfaction, thus leading to an increased level of one's well-being and QoL. 57 58 In the general population, psychological conditions such as depression, anxiety, ability to cope, and engaging in physical activity have been significantly associated with work participation. 59 60 Velvin et al reported that 41 to 58% of adults with MFS are employed compared with 79% in the general Norwegian population. 57 The authors also reported that many adults with MFS retire earlier than their peers. 57 This finding is consistent with other literature on the employment rate of MFS patients. 8 10 12 40 Further, decreased rates of employment have been associated with mental illness. 61 Peters et al noted that 20% of their respondents perceived instances of workplace discrimination. 40 Furthermore, Peters et al found that workplace discrimination was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms, low self-esteem, striae, negative outlook toward MFS, and perceptions of workplace discrimination. 40

Goldfinger et al argued that individuals who were unable to work due to disability were more likely to have more severe features of MFS. 22 Rao et al found in their study that 89% of their respondents had to reduce their weekly work hours; 45% stated this reduction was due to MFS. 21 Rao et al found that 82% of the respondents missed on average 6.5 ± 7 months of work because of their MFS-related treatment; of that 82%, 53% had aortic root surgery, 9.5% back surgery, and 6.3% aortic valve replacement. 21

Anticipation of potential aortic dissection could lead to decreased satisfaction with life and increased anxiety, even though it has yet to be associated with work participation. 11 49 57 Interestingly, even though aortic complications and surgery, vision problems, and chronic pain have not been found to be associated with work participation; fatigue, level of education, and age have been found to impact work participation. 57 Velvin et al concluded that the aortic complications may be underestimated by patients, vision problems may be due to improvements in optic devices and glasses, and MFS patient with chronic pain accept it as part of the disease; all of which may not impact work participation. 57

Perceptions of self are also related to various aspects of QoL and thus, are an important consideration for MFS given the phenotypic presentation. De Bie et al found that MFS participants generally reported to have positive self-image although 63% wished to have more self-confidence. 56 Adults with MFS also have negative views of their appearance, in particular the MFS features of striae and pectus deformity have been reported to cause negative self-image and self-esteem. 6 7 40 Of note, surgical correction of pectus deformities have been shown to improve QoL and self-esteem for patients in the general population. 62 De Bie et al also reported that 90% of the participants noted that MFS has had a negative impact on their sexual relationships and 50% of the participants claimed to be displeased with their body image. 56 Similarly, Peters et al reported that MFS patients with striae, back pain, or lower quality of life demonstrated problems with lack of sex drive which impacted QoL. 12 Both physical and cognitive interventions related to these issues of self-perception might improve QoL for MFS patients.

Psychiatric Aspects of MFS

Of the literature reviewed addressing the adult population with MFS, 16 articles mentioned psychiatric or psychological components of MFS. 6 7 8 11 12 14 16 19 21 22 23 29 40 49 51 56 Gritti et al reviewed 13 different case reports and other literature that dealt with psychiatric and neuropsychological issues. They found that psychiatric symptoms are an important consideration as it can impact patients QoL and adherence to treatment. 16 Therefore, they argued for a multidisciplinary approach to MFS. Excluding case studies and case reports, there have been an additional seven articles that examined the psychiatric and psychological components of MFS. 11 19 21 22 23 29 49 Because there is still debate on the exact relationship between certain psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and MFS, the prevalence of comorbidity is unknown. Additionally, it is difficult to determine the rate of comorbidity based on case studies or case reports (e.g., Gritti et al review). 16 Commonly prescribed antipsychotics can cause prolonged QTc (QT interval corrected for rate), which is an especially important consideration as MFS patients with the Fibrilin-1( FBN1 ) mutation, the most common mutation causing MFS, have an increased risk of developing prolonged QTc and ventricular arrhythmias. 63 64 Further, patients with schizophrenia have a greater mortality from cardiovascular disease and low rates of treatment and screening, which may be due to noncompliance with MFS recommended treatment. 65 66

Eight of the 16 articles specifically mention features of anxiety or depression. 6 11 19 21 22 23 29 51 Velvin et al found in their study that satisfaction with life was decreased in MFS individuals that met with a psychologist implying that these individuals could have some type of psychological distress. 49 A study by Peters et al found that patients with MFS reported overall higher rates of depression, 44% of their study population, and demonstrated a significant correlation between depression and mitral valve prolapse. 6 Rand-Hendriksen et al demonstrated in their study a relatively high level psychological distress, in particular high anxiety scores in female MFS patients. 51 Rao et al noted that female patients showed greater concern for depression. 21 These findings are consistent with Moon et al who found that both anxiety and depression were biobehavioral variables affecting QoL in MFS. 23 Moon et al also reported that 98% MFS patients experienced depression when including borderline depression. However, results are inconsistent as only 25% of the Goldfinger et al participants reported experiencing depression. 22 23 In a study conducted by Kelleher et al, suicide or suicidal posts were minimal, but health care providers should still be aware of this concern and conduct proper screening. 29 Trait anxiety also has been demonstrated in MFS patients who received acute life-saving surgery. 11 In these MFS patients with history of aortic dissection, patient have a negative view regarding the controllability of their disease.

Patients' subjective perceptions of the severity of the disease can have great impact on their lives, mainly in domains of mental well-being and willingness to adhere to treatment. 6 This demonstrates that patients who received acute life-saving surgery, and thus perceive the disease to be more severe, may require increased mental health screening and management. Additionally, the presence of pain in multiple locations on the body puts patients at risk for developing psychiatric illnesses such as depression and anxiety. 19 67 Therefore, screening for depression and/or anxiety may be important in patients with MFS.

Coping

Of the literature reviewed and categorized into adults theme, seven articles mentioned coping strategies adopted by individuals with MFS. 7 8 13 14 23 25 27 Young individuals coping with any chronic illness typically utilize maladaptive coping strategies, such as denial and isolation as their main coping mechanisms. Velvin et al, Van Tongerloo et al, Giarelli et al, and Schneider et al report that despite the psychologically distressing aspects of their diagnosis, most MFS patients are able to manage their psychological stressors after diagnosis. 7 8 13 14 In chronic illness patients, decreasing the level of uncertainty leads to increasing the activation of positive coping mechanisms, which can improve QoL. 68 Using the positive psychology model, focusing on positive traits and predispositions can be more effective than treating negative coping mechanisms. In particular, it has been demonstrated that individuals with chronic illness who possess traits of forgiveness and gratitude, have a higher QoL. 69 Stanišić et al argued in their study that the MFS individuals exhibited a higher than average satisfaction with life because they learn to cope with their circumstances and rely on self-efficacy as a form of coping. 27 Interventions that promote these traits could be beneficial in ameliorating maladaptive coping mechanisms, increasing a positive well-being, and enhancing the QoL.

In a recent pilot study, MFS patients received rehabilitation for physical fitness and psychological well-being, which resulted in improved physical fitness, QoL, and psychological wellbeing. 25 They specifically noted changes for anxiety and depression, fatigue, nociception, and vitality domains of QoL. 25 Incorporating physical fitness and well-being rehabilitation as coping skills in patients with MFS may prove to optimize both physical and mental health. Psychosocial support and coping mechanism development to cope with the fatigue and pain related to MFS might lead to increased QoL.

Family Environment and Social Support

Family Planning

Of the literature reviewed addressing the family environment and social support theme, three articles mention the aspects of family planning in consideration with MFS. 12 28 56 Family planning can be an important consideration for individuals with chronic genetic disorders like MFS. De Bie et al interviewed 220 women ≥ 25 years of age with MFS who had been pregnant. 56 Of the 430 pregnancies that were recorded, only seven were reported to have cardiac problems related to aortic or valvular disease. 56 Treasure et al (2018) argue that valve sparing surgery and anticoagulation after aortic surgery may be important considerations for individuals with MFS who are wanting to get pregnant. 28 Interestingly, De Bie et al found that women with MFS who had a positive family history of MFS became pregnant more often compared with the women with MFS without a family history. 56 Although the cause of this finding is unclear, it may indicate that women with de novo MFS may need additional support and exposition of their condition and reproductive decision-making. 12 56

Another consideration is the level of uncertainty MFS patients have toward passing on MFS to offspring and uncertainty of the course of disease which could potentially play a role in reproductive decision-making. Peters et al suggest that the patient perception of their family experience with MFS may influence their reproductive decision-making. 12 A possible explanation is that patients with a de novo mutation may have more uncertainty of the clinical course of the disease due to not being able to witness other family members cope with the same disease. Uncertainty with MFS has not been studied directly and needs more research to draw firm conclusions.

Peters et al found that 62% of their respondents state MFS affected their reproductive decision-making. 12 De Bie et al and Peters et al found that early diagnosis with MFS was associated with a lower pregnancy rate. 12 56 One possible explanation is that these patients with the de novo mutation were diagnosed at an earlier age compared with those with familial inheritance because families may dismiss the symptoms and phenotypic features as just familial aspects instead of being a facet of disease. 12 56 They also noted that individuals who were diagnosed at a younger age may have more severe symptoms, which could potentially have an impact on their reproductive decision-making. Additionally, female MFS patients express concerns about childbearing risks on their life and passing it on to their offspring which can influence the psychosocial QoL. 12 Despite the reproductive concerns and negative aspects of diagnosis, De Bie et al and Peters et al note participants have lived relatively normal family lives and approximately half of the adult participants with MFS have children. 12 56

Familial and Social Support

Of the literature reviewed addressing family environment and social support theme, six articles mention the use of familial or social support to reduce stress associated with MFS. 12 13 23 38 40 56 De Bie et al found that at least 58% of participants had one relative with MFS. 57 Peters et al found that the family environment for those that have MFS did not significantly differ from adults in the general population. 12 However, hospitalization, constant medical care, and frequent medical appointments can be emotionally taxing and stressful for caregivers. In many cases with chronic illnesses, uncertainty of the course of the disease has been reported to be a large stressor for a patient's mother resulting in psychological and physical symptoms. 70

Giarelli et al examined the transition to self-management for MFS adolescents as they become adults. 13 38 They identified some of the negative factors caused by parent or family circumstances that have an impact on MFS patients' ability to transition into managing their condition, such as the loss of a spouse or other family member due to MFS, denial of the severity of MFS, anxiety, over-protectiveness of the caregiver, lack of knowledge, lack of health insurance, disrupted family relations, and difference in opinion between parents on treatment. 38

Children with a chronic disorder and their families encounter the same attributes that affect their lives such as monitoring symptoms, daily treatment regimen, education of MFS, uncertainty related to MFS, implications of MFS that impact school, peer, and familial relationships. 13 Although an individual may be vulnerable to negative stressful outcome, this tendency can be mitigated by having significant relationships. This indicates that family members can have a drastic impact on a child's resilience depending on their bond and relationship with the child. Individuals at younger stages of adolescents rely on family for social support. 71 Many children with MFS have a sibling or other family member with the same condition. 8 These children may seek comfort with this individual in their family which can increase the child's resilience. Giarelli et al noted that children with cardiac involvement had a positive impact when provided with advice from an affected parent. 13 Interacting with someone at an older age with MFS who might share his/her experience with MFS may decrease the level of uncertainty-related stressors as it is easier to discern the outcome and progression of the disease. Future research could focus on a comparison of individuals with MFS and how siblings with and without MFS affect their coping.

In other illness uncertain populations, where the disease course across the lifespan is uncertain, social support interventions can have a positive impact on patient's psychological distress. 72 73 74 However, there may be sex related differences in social interaction with MFS patients. 9 18 Peters et al study found that 43% of their respondents spent time with others with MFS, but this was significantly correlated with being female. 40 Moon et al also demonstrated that social support had an impact on depression in MFS patients, although 62.8% of their study population was male. 23 Strong social support has been shown have a positive impact on functional impairment particularly for those suffering with depression. 75 Communities of individuals affected by MFS can make a significant impact by providing much needed social support.

Coping Mechanisms of the Caregiver

Of the literature reviewed addressing the family environment and social support theme, two articles mention coping mechanisms or concerns of the parent/caregiver of patients with MFS. 13 26 Johansen et al conducted a comparison of satisfaction with life of caregivers of children with MFS and found that there was no significant difference when compared with the general Norwegian population. 26 However, this study used a small size ( N = 10) and did not report whether these caregivers also had MFS or their children had a de novo mutation.

Nabors et al identified five factors that have been reported to be associated with maladaptive coping for caregivers of children suffering from chronic illness. These include being far from home, difficulty related to witnessing the child's medical problem/pain, emotional or financial stress, siblings not understanding the depth of care required for the severity of the illness, and difficulty interacting with medical personnel. 76 Although the difficulty of witnessing a child's medical problem has not been evaluated in MFS individuals, it may have an impact as there have been multiple cases of aortic dissection in patients with MFS under the age of 25. 77 Within the MFS population, emotional or financial stress and siblings not understanding the depth of care required for the severity of the illness have been examined. As such, only these maladaptive coping mechanisms will be discussed here.

A frequent stressor of the caregivers is financial strain. The MFS population overall has increased health care expenditure, likely related to prolonged length and frequency of inpatient stays, increased physician contact, and additional prescriptions compared with the control population. 78 Further, Giarelli et al noted that caregivers of MFS children reported health insurance was their greatest worry. 13 De Bie et al demonstrated that 30% of participants had difficulties obtaining life insurance and 16% obtaining medical insurance due to MFS. 56 Although this study was conducted with an adult sample, it is likely that caregivers and the pediatric MFS population might face similar difficulties of obtaining insurance which will increase financial strain.

A common emotional stressor on the caregiver is the impact of the chronic illness diagnosis on the siblings of the patient. 76 Many a times, siblings of the patient do not understand the medical situation and may not understand why, for instance, they are not getting as much attention as their sibling which can place stress on the caregiver. Patients with MFS report feeling able to share their feelings with siblings similarly compared with the general population. 12 It is possible that the MFS population and their caregivers do not experience this stressor as much as other populations because of the familial component of the disease. In future studies, it may be beneficial to evaluate caregiver's experience of de novo MFS patients compared with caregiver's experience of familial MFS patients. Due to the paucity of information on caregivers of individuals with MFS, further research is required to identify possible struggles that these caregivers may experience that can impact the overall care of the patient.

Providers Caring for Patients with MFS

Role of the Health Care Provider

Four articles categorized into the “Providers caring for patients with MFS” theme mention the impact or role a health care provider can have on MFS patients. 13 28 38 79 As MFS is a lifelong condition, it is important for the provider to be willing to aid in the transition of care as that patient grows and takes more responsibility for their own treatment and care. The health care provider should educate both the parent and children on the symptoms of MFS, reasoning behind pharmacotherapy and adherence, restriction in activity and monitoring of the progression of MFS. 38 The role of the health care provider is not only to provide clinical management but also to help the patient and family cope with the MFS diagnosis and its several manifestations. Giarelli et al suggested that the psychosocial process that constituted to the adolescent's ability to become physically fit and fitting in socially were influenced by the readiness of child to accept responsibility, the readiness of parents to relinquish and trust their child, and ability to pay and access to services. 13 This illustrates the importance of health care providers influencing the transition to self-management for individuals with MFS. Clinicians could help decrease uncertainty-related stress by comprehensively communicating with caregivers and patients regarding the expected trajectory of the condition. 73 80

Providing information on the course of the condition and addressing familial concerns may reduce stressors. Treasure et al also recommend that providers take patients preferences, such as child bearing and having an active lifestyle into account when considering aortic surgical inventions. 28 Von Kodlitsch et al illustrated the medical standards for each of the various disciplines that are involved with multidisciplinary health care teams for MFS. 81 Due to the potential risk on the mother with MFS and the risk of passing on the disorder to her children, providers should discuss family planning and pregnancy with affected couples, to ensure that every woman with MFS is aware of her own personal risk. 81 Providing adequate information about health care providers who specialize in MFS by age group may be beneficial to aid in patient care and educate patients on self-surveillance and self-management as they mature from a child to adult. 13 38 79 A multidisciplinary team can ensure the best approach to help establish a strong family unit and resilience for the patient and caregiver.

Medication Adherence

Four articles categorized into the “Providers caring for patients with MFS” theme mention the importance of adherence to medications. 7 8 13 47 However, the participants in these studies are primarily adolescents and additional studies are needed to determine other age groups' adherence. Clinicians can directly impact their patient's compliance with the medical treatment. The initial regimen discussion between the physician and the patient has been associated with both the patients' initiation of the medication and long-term adherence. Focusing on all aspects of the treatment including benefits and clinical course make a positive impact on adherence. 82 Adolescents may find it difficult to comply with physical limitations and medications when they did not experience physical discomfort or symptoms from the disease illustrating the importance of acceptance. 7 13 47 Peters et al found that the treatment adherence rate in MFS patients is higher than that of the general population. 47 In both adolescent and adult populations, the majority of MFS patients have compliant with their medications; however, noncompliance can occur due to an individual trying regain a sense of control over their life. 8 13 47 Adolescents tend to take more risks than adults and teens with MFS. They could potentially take a risk of noncompliance and comprise their cardiovascular health. 13 Therefore, adherence strategies such as peer groups should always be implemented and encouraged. 83 84 Parental support and engagement is important in increasing both adherence and a child's knowledge of condition. 85 Caregiver reminders have been reported to be a major contributor to improved compliance among adolescents with chronic conditions. 7

Conclusions

In this manuscript, we reviewed the literature on psychosocial factors that impact MFS patients and their families. Due to the phenotypic features of MFS and needing lifelong treatment starting at a young age, young individuals with MFS may experience difficulties with social interactions as a result. As such, studies have indicated that children and adolescents can have a negatively impacted QoL thus appropriate interventions should be made.

As MFS patients mature, other symptoms can have an impact of their life. Adults with MFS experience chronic pain, which negatively impacts QoL. Fatigue associated with MFS can have an impact of an individual's work participation and their satisfaction with life. Due to the nature of treatment and symptoms of MFS, psychiatric and psychological distress may develop. Coping with MFS and implementing positive coping mechanisms may be beneficial for physical fitness, QoL and psychological well-being. Understanding these various implications, targeted therapies can be designed to help improve emotional and psychological well-being, leading to increased QoL.

Individuals affected by MFS are likely to have their diagnosis influence family planning. Parents and siblings of MFS patients are exposed to different types of stressors due to the chronicity of MFS. These experiences may have long-term implications for patients and their family members. Thus, coping with the psychosocial stress in a timely fashion should be an important component of routine care for these patients.

QoL of family members related to someone with a chronic illness is lower, specifically, in self-expression, individual growth, and realization of their potentials. 86 Therapy inventions can target those identified areas to resolve emotional and personal conflicts which could prevent emotional burnout. 87 Individualized therapy could focus on other topics unique to the caregiver population, such as the stress between commitment to the sick relative and the needs of the other members in the family. Positive coping factors that have been shown to help caregivers are support from family and friends, assistance from hospital staff, and faith or religion. 76 Social and familial support could be key component to improving the life of patients with MFS and their caregivers. Patients and family members can be encouraged by physicians to incorporate positive coping mechanisms. Health care providers may improve quality of treatment by spending additional time with patients and their families to improve adherence and encourage the transition of care as the patient matures.

Limitations

This review is subject to the same limitations of the journal articles that were used in the synthesis of this manuscript, such as possible self-selection bias. Using systematic review criteria checklists, such as Cochrane or PRISMA could enhance the quality of the current review. C.N. was the only author who participated in study selection, study screening, and thematic analysis, which may be a possible limitation as this introduces more bias having a single participant in this section of the literature review. Having additional researchers contribute to the study selection, thematic analysis and conducting a critical analysis would reduce possible bias.

Search terms were used to provide a robust and thorough search of the literature. It is possible that the search databases do not include all articles on the topic of MFS; however, multiple search databases were used to address this. An additional concern when utilizing search terms is the possible bias in selecting search terms and possibly omitting other terms that would be beneficial for compiling articles on the potential topic. We aimed to avoid this by using multiple search terms and databases. Only articles that were published in English were included in this review.

Critical analysis was not conducted in the study, which is a possible limitation as this allows for possible introduction of articles with questionable or invalid study designs. It should be noted that many of the articles selected in this review have undergone critical analysis from one of the four previous reviews. While critical analysis was not conducted, we were able to include more articles as MFS is a rare genetic condition with limited studies that may have been eliminated in a critical analysis. As larger studies on MFS become available, critical analysis of those studies can be conducted. We did not include case studies and case reports in this review, which may be another possible limitation which may have caused us to overlook potentially informative findings.

Individuals willing to participate in MFS studies may be better able to cope with the disorder, whereas those who are not coping well might be less likely to seek treatment or participate in surveys/studies. As such, some studies did not stratify data based on age groups. Additionally, not all studies included verified diagnosis of MFS patients. Some of the studies were conducted across various countries, which may be impacted by different sociological and cultural interpretations of certain factors, such as pain or fatigue. 88 Due to the variety of studies included in this review, multiple validated measurements of QoL were used. Future studies should implement a specific validated instrument on QoL in MFS to control for variability between studies and allow for meta-analysis.

Recommendations

Clinicians may decrease the amount of psychological distress by spending additional time with these families to explain the course of the disease, potential complications, and management options. Formal pain management should be considered and implemented to improve both physical and mental health of these patients. Psychological and coping strategies can be offered to these patients to help manage the stress involved. Supportive groups and educational information may be supplied to family members and caregivers to ameliorate burnout and increase familial resilience.

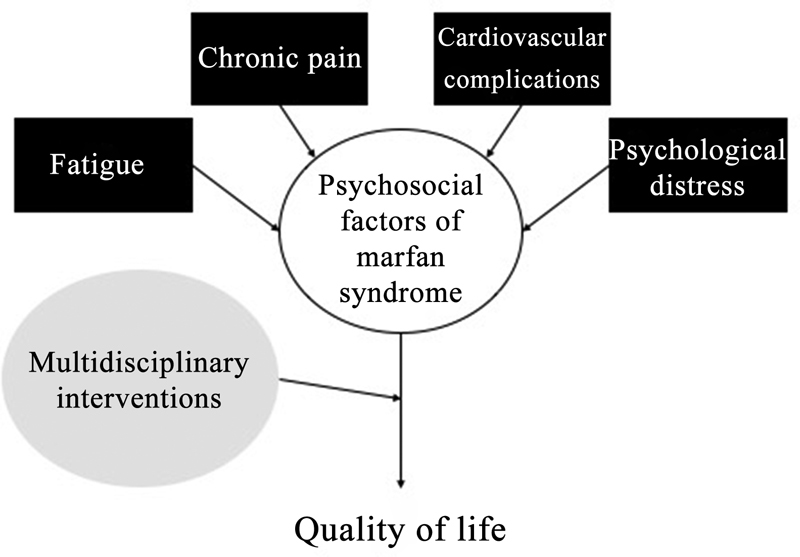

MFS affects multiple organ systems and each case can present with unique symptoms; therefore, this calls for further integration and awareness of medical professionals across multiple disciplines for optimal management as demonstrated in Fig. 2 . Consolidating and making a uniform and syndrome specific QoL, validated measurement instrument would be beneficial to allow for meta-analysis and further consolidation of studies. Utilizing questionnaires, surveys, or an inventory on coping mechanisms, such as the COPE Inventory during clinic visits could be beneficial to understand how MFS patients and their caregivers respond to stress and determine whether an intervention could be helpful. 89

Fig. 2.

Psychosocial factors associated with Marfan syndrome . There are several important psychosocial factors associated with Marfan syndrome. A multidisciplinary approach that target all these aspects may improve the quality of life in this population.

Conflict of Interest None declared.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures or relationship with industry.

References

- 1.Loeys B L, Dietz H C, Braverman A C et al. The revised Ghent nosology for the Marfan syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47(07):476–485. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.072785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judge D P, Dietz H C.Marfan's syndrome Lancet 2005366(9501):1965–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Paepe A, Devereux R B, Dietz H C, Hennekam R C, Pyeritz R E. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;62(04):417–426. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960424)62:4<417::AID-AJMG15>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Treasure T, Takkenberg J J, Pepper J. Surgical management of aortic root disease in Marfan syndrome and other congenital disorders associated with aortic root aneurysms. Heart. 2014;100(20):1571–1576. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martikainen P, Bartley M, Lahelma E. Psychosocial determinants of health in social epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(06):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters K F, Kong F, Horne R, Francomano C A, Biesecker B B. Living with Marfan syndrome I. Perceptions of the condition. Clin Genet. 2001;60(04):273–282. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider M B, Davis J G, Boxer R A, Fisher M, Friedman S B. Marfan syndrome in adolescents and young adults: psychosocial functioning and knowledge. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1990;11(03):122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Tongerloo A, De Paepe A. Psychosocial adaptation in adolescents and young adults with Marfan syndrome: an exploratory study. J Med Genet. 1998;35(05):405–409. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.5.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fusar-Poli P, Klersy C, Stramesi F, Callegari A, Arbustini E, Politi P. Determinants of quality of life in Marfan syndrome. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(03):243–248. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.49.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bathen T, Velvin G, Rand-Hendriksen S, Robinson H S. Fatigue in adults with Marfan syndrome, occurrence and associations to pain and other factors. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(08):1931–1939. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benke K, Ágg B, Pólos M et al. The effects of acute and elective cardiac surgery on the anxiety traits of patients with Marfan syndrome. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(01):253. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1417-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peters K F, Kong F, Hanslo M, Biesecker B B. Living with Marfan syndrome III. Quality of life and reproductive planning. Clin Genet. 2002;62(02):110–120. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giarelli E, Bernhardt B A, Mack R, Pyeritz R E. Adolescents' transition to self-management of a chronic genetic disorder. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(04):441–457. doi: 10.1177/1049732308314853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velvin G, Bathen T, Rand-Hendriksen S, Geirdal A O. Systematic review of the psychosocial aspects of living with Marfan syndrome. Clin Genet. 2015;87(02):109–116. doi: 10.1111/cge.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velvin G, Bathen T, Rand-Hendriksen S, Geirdal A O. Systematic review of chronic pain in persons with Marfan syndrome. Clin Genet. 2016;89(06):647–658. doi: 10.1111/cge.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gritti A, Pisano S, Catone G, Iuliano R, Salvati T, Gritti P. Psychiatric and neuropsychological issues in Marfan syndrome: a critical review of the literature. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2015;50(04):347–360. doi: 10.1177/0091217415612701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller G C, Steiner K, Wild J M, Stark V, Kozlik-Feldmann R, Mir T S. Health-related quality of life is unimpaired in children and adolescents with Marfan syndrome despite its distinctive phenotype. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(03):311–316. doi: 10.1111/apa.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handisides J C, Hollenbeck-Pringle D, Uzark K et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Young Adults with Marfan Syndrome. J Pediatr. 2019;204:250–2550. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speed T J, Mathur V A, Hand M et al. Characterization of pain, disability, and psychological burden in Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(02):315–323. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.38051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratiu I, Virden T B, Baylow H, Flint M, Esfandiarei M. Executive function and quality of life in individuals with Marfan syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(08):2057–2065. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1859-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao S S, Venuti K D, Dietz H C, III, Sponseller P D. Quantifying health status and function in Marfan Syndrome. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2016;25(01):34–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldfinger J Z, Preiss L R, Devereux R B et al. Marfan Syndrome and quality of life in the GenTAC Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(23):2821–2830. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon J R, Cho Y A, Huh J, Kang I S, Kim D K. Structural equation modeling of the quality of life for patients with Marfan syndrome. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:83. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0488-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghanta R K, Green S Y, Price M Det al. Midterm survival and quality of life after extent II thoracoabdominal aortic repair in Marfan Syndrome Ann Thorac Surg 2016101041402–1409., discussion 1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benninghoven D, Hamann D, von Kodolitsch Y et al. Inpatient rehabilitation for adult patients with Marfan syndrome: an observational pilot study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(01):127. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0679-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansen H, Dammann B, Andresen I-L, Fagerland M W. Health-related quality of life for children with rare diagnoses, their parents' satisfaction with life and the association between the two. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11(01):152. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanišić M-G, Rzepa T, Gawrońska A et al. Personal resources and satisfaction with life in Marfan syndrome patients with aortic pathology and in abdominal aortic aneurysm patients. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2018;15(01):27–30. doi: 10.5114/kitp.2018.74672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Treasure T, King A, Hidalgo Lemp L, Golesworthy T, Pepper J, Takkenberg J J. Developing a shared decision support framework for aortic root surgery in Marfan syndrome. Heart. 2018;104(06):480–486. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelleher E, Giampietro P F, Moreno M A. Marfan syndrome patient experiences as ascertained through postings on social media sites. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(11):2629–2634. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song H K, Kindem M, Bavaria J E et al. Long-term implications of emergency versus elective proximal aortic surgery in patients with Marfan syndrome in the Genetically Triggered Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Cardiovascular Conditions Consortium Registry. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(02):282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schoormans D, Radonic T, de Witte P et al. Mental quality of life is related to a cytokine genetic pathway. PLoS One. 2012;7(09):e45126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velvin G, Wilhelmsen J E, Johansen H, Bathen T, Geirdal A O. Systematic review of quality of life in persons with hereditary thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection diagnoses. Clin Genet. 2019;95(06):661–676. doi: 10.1111/cge.13522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winchester C L, Salji M. Writing a literature review. J Clin Urol. 2016;9(05):308–312. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pautasso M. Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9(07):e1003149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nowell L S, Norris J M, White D E, Moules N J. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(01):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(01):45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(03):398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giarelli E, Bernhardt B A, Pyeritz R E. Attitudes antecedent to transition to self-management of a chronic genetic disorder. Clin Genet. 2008;74(04):325–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barber B L, Eccles J S, Stone M R. Whatever happened to the Jock, the Brain, and the Princess?: Young adult pathways linked to adolescent activity involvement and social identity. J Adolesc Res. 2001;16(05):429–455. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peters K, Apse K, Blackford A, McHugh B, Michalic D, Biesecker B. Living with Marfan syndrome: coping with stigma. Clin Genet. 2005;68(01):6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kristofferzon M L, Lindqvist R, Nilsson A. Relationships between coping, coping resources and quality of life in patients with chronic illness: a pilot study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25(03):476–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(07):645–649. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medvedev O N, Landhuis C E. Exploring constructs of well-being, happiness and quality of life. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4903. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yildirim Y, Kilic S P, Akyol A D. Relationship between life satisfaction and quality of life in Turkish nursing school students. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15(04):415–422. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senín-Calderón C, Rodríguez-Testal J F, Perona-Garcelán S, Perpiñá C. Body image and adolescence: a behavioral impairment model. Psychiatry Res. 2017;248:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prazeres A M, Nascimento A L, Fontenelle L F. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a review of its efficacy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:307–316. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S41074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters K F, Horne R, Kong F, Francomano C A, Biesecker B B. Living with Marfan syndrome II. Medication adherence and physical activity modification. Clin Genet. 2001;60(04):283–292. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson A M, Walega D R, McCarthy R J. The incidence and severity of physical pain symptoms in marfan syndrome: a survey of 993 patients. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(12):1080–1086. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Velvin G, Bathen T, Rand-Hendriksen S, Geirdal A O. Satisfaction with life in adults with Marfan syndrome (MFS): associations with health-related consequences of MFS, pain, fatigue, and demographic factors. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(07):1779–1790. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1214-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Percheron G, Fayet G, Ningler T et al. Muscle strength and body composition in adult women with Marfan syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(06):957–962. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rand-Hendriksen S, Sørensen I, Holmström H, Andersson S, Finset A. Fatigue, cognitive functioning and psychological distress in Marfan syndrome, a pilot study. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(03):305–313. doi: 10.1080/13548500600580824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Dijk N, Boer M C, Mulder B J, van Montfrans G A, Wieling W. Is fatigue in Marfan syndrome related to orthostatic intolerance? Clin Auton Res. 2008;18(04):187–193. doi: 10.1007/s10286-008-0475-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foran J R, Pyeritz R E, Dietz H C, Sponseller P D. Characterization of the symptoms associated with dural ectasia in the Marfan patient. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;134A(01):58–65. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rand-Hendriksen S, Johansen H, Semb S O, Geiran O, Stanghelle J K, Finset A. Health-related quality of life in Marfan syndrome: a cross-sectional study of Short Form 36 in 84 adults with a verified diagnosis. Genet Med. 2010;12(08):517–524. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ea4c1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verbraecken J, Declerck A, Van de Heyning P, De Backer W, Wouters E F. Evaluation for sleep apnea in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and Marfan: a questionnaire study. Clin Genet. 2001;60(05):360–365. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Bie S, De Paepe A, Delvaux I, Davies S, Hennekam R C. Marfan syndrome in Europe. Community Genet. 2004;7(04):216–225. doi: 10.1159/000082265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Velvin G, Bathen T, Rand-Hendriksen S, Geirdal A O. Work participation in adults with Marfan syndrome: demographic characteristics, MFS related health symptoms, chronic pain, and fatigue. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(12):3082–3090. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reitzes D C, Mutran E J. Self and health: factors that encourage self-esteem and functional health. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(01):S44–S51. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.1.s44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]