Abstract

Objective:

Detection of cognitive impairment suggestive of risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression is crucial to the prevention of incipient dementia. This study was performed to determine if performance on a novel object discrimination task improved identification of earlier deficits in older adults at risk for AD.

Method:

135 participants from the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center [Cognitively Normal, Pre- Mild Cognitive Impairment (PreMCI), amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI), Dementia] completed a test of object discrimination and traditional memory measures in the context of a larger neuropsychological and clinical evaluation.

Results:

The Object Recognition and Discrimination Task (ORDT) revealed significant differences between the PreMCI, aMCI, and dementia groups versus cognitively normal individuals. Moreover, relative risk of being classified as PreMCI rather than cognitively normal increased as an inverse function of ORDT score.

Discussion:

Overall, the obtained results suggest that a novel object discrimination task improves the detection of very early AD-related cognitive impairment, increasing the window for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Dementia, temporal lobe, memory, perirhinal cortex, visual perception, early diagnosis

Introduction

Numerous clinical trials involving Alzheimer’s disease (AD) therapeutics have failed due to an inability to reverse clinical symptoms and gross cellular dysfunction once they are present (Schneider et al., 2014). As a result, investigators have attempted to target groups of older adults earlier in the disease process, at an intermediate stage of cognitive decline between cognitively normal aging and clinical dementia. These older adults are at greater risk of progressing to AD-related dementia compared to cognitively normal individuals, and can be classified as “amnestic mild cognitive impairment (aMCI)” or “pre- mild cognitive impairment (PreMCI).” Individuals who meet research criteria for PreMCI may have subjective cognitive deficits with normal-range performance on cognitive assessments and, therefore, do not meet formal diagnostic criteria for aMCI. Individuals with PreMCI may also be identified by having non-normal performance on cognitive assessments without subjective cognitive decline, cognitive decline identified by knowledgeable informants, or clinically-identified impairment. Crucially, individuals with PreMCI are 6 times more likely to progress to aMCI or dementia over time compared to their cognitively normal peers (Loewenstein et al., 2012). Individuals with aMCI are 7 times more likely to progress to dementia compared to their cognitively normal counterparts (Duara et al., 2011). Identifying neurocognitive probes that are sensitive to decline at such early stages is a critical step in identifying patients who may benefit from therapeutics designed to prevent or delay AD onset (Snyder et al., 2014).

Memory impairment figures prominently into the diagnostic criteria of aMCI (Caselli et al., 2014), since the site of the earliest appearance of tangle pathology in AD is the transentorhinal cortex, or Area 35 of the perirhinal cortex, which is a major source of input into the hippocampal memory system (Braak & Braak, 1991; Khan et al., 2014). Notably, studies in patients diagnosed with prodromal aMCI revealed atrophy in the medial aspect of the perirhinal cortex prior to the lateral perirhinal cortex (Krumm et al., 2016). Additionally, regional tau deposition has been shown to correlate with atrophy of bilateral PRC in early AD (Sone et al., 2017), and has been shown to be relatively better than amyloid accumulation in predicting future cognitive decline (Huber, Yee, May, Dhanala, & Mitchell, 2017; Qiu et al., 2017). Therefore, investigating early sites of tau deposition like the PRC is critical to identifying early markers of AD-related cognitive decline.

The PRC is located on the ventral surface of the temporal lobe, lateral to the entorhinal cortex and anterior to the parahippocampal cortex. The PRC receives its primary inputs from unimodal sensory systems, such as the primary visual cortex and visual association cortices, which it then conveys to downstream brain regions as multimodal, three-dimensional object representations based on specific features of the perceived stimulus. The role the PRC plays in feature-binding is important in object recognition and discrimination, as this computation leads to the identification of objects based on unique configurations of features (Barense, Henson, Lee, & Graham, 2010; Devlin & Price, 2007). Results of primate and rodent experiments show that the PRC is more active when discriminating among objects that share common features (Buckley & Gaffan, 1997; Bussey, Saksida, & Murray, 2003; Cowell, Bussey, & Saksida, 2006). Interestingly, the medial PRC, which is more vulnerable to early AD disease processes, has been specifically shown to be associated with disambiguation of confusable object (Kivisaari, Tyler, Monsch, & Taylor, 2012). The perirhinal cortex has also been shown to support recognition of the same object presented from different viewpoints, allowing for the identification of a unique object that shares features with rotated copies of a non-target object in an oddity discrimination task in human (Lee, Barense, & Graham, 2005) and animal studies (Buckley, Booth, Rolls, & Gaffan, 2001). The location of the PRC at the anatomical nexus of cortical inputs to the medial temporal lobe memory system, as well as its involvement in processing 3D object representations, supports the involvement of the PRC in both mnemonic and visual-perceptual abilities (Bussey et al., 2003; Murray & Bussey, 1999). As a result, tasks that tap such ‘pre-mnemonic’ processes, like object recognition and discrimination, may have additional utility in the detection of incipient cognitive impairment. In fact, it has been argued that evaluating the structure and function of the ventral processing stream may reveal subtle deficits present in very early AD (Kurylo, Corkin, Rizzo Iii, & Growdon, 1996) and cognitively impaired aging (Fidalgo, Changoor, Page-Gould, Lee, & Barense, 2016).

In human clinical studies, when lure items share a high degree of featural similarity with the familiar target items, individuals at risk for AD present with high rates of false recognition, tending to recognize novel objects as familiar (Yeung, Ryan, Cowell, & Barense, 2013). These studies suggest that PRC dysfunction may underlie recognition memory and perceptual deficits that are common in early AD. However, few researchers have implemented object discrimination tasks in humans to aid in identification of risk of AD progression (Mason et al., 2017; Newsome, Duarte, & Barense, 2012), and no studies have investigated the sensitivity of these tasks to more subtle cognitive changes seen in PreMCI.

The Object Recognition and Discrimination Task (ORDT) used in this study is modeled after similar tasks used in rodent (Bartko, Winters, Cowell, Saksida, & Bussey, 2007; Johnson et al., 2017) and primate (Burke et al., 2011; Bussey et al., 2003) literature and adapted from a visual discrimination (“oddity”) task first used in humans by Devlin and Price (Devlin & Price, 2007). The purpose of the current investigation was to determine the utility of the ORDT in the identification of very early cognitive changes seen in PreMCI and aMCI participants. Our central hypothesis was that the ORDT would contribute to the prediction of current early cognitive change because it taps key functions of the PRC.

Method

One hundred forty-three (143) participants from the Wien Center for Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida were recruited as part of the NIA-sponsored 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (1Florida ADRC). The sample was 40% male and 56% Hispanic/Latino. IRB approval was obtained at the Mount Sinai Medical Center, and allowed for sharing of de-identified patient information with collaborators at the University of Florida. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and study partners.

Participants

All participants had an informant age 18 or older who could be present at the participant’s first appointment and provide reliable collateral information. Participants were able to read at the 6th grade reading level [Wide Range Achievement Test, 4th edition (WRAT-IV; (Wilkinson & Robertson, 2006) for English speakers, and the Woodcock-Muñoz Language Survey- Revised (WMLS-R; Woodcock, Muñoz-Sandoval, Ruef, & Alvarado, 2005) or Word Accentuation Test [WAT; Krueger, Lam, & Wilson, 2006) for Spanish speakers]. If on medications, participants were required to be on steady dosages for 2 months or longer, and participants were not excluded if they were on memory-enhancing drugs. This included acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or other related medications that are prescribed by physicians for the treatment of MCI. Additional demographic and descriptive data is contained in Table I.

Table I: Participant Demographic Information.

Participant demographic information illustrated for all 135 participants included in the final analyses. CN = Cognitively Normal; PreMCI = pre- Mild Cognitive Impairment; aMCI = amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment; E = English; S = Spanish; M = Male; F = Female; RT= Reaction Time. NOTE: Error terms included are standard deviation.

| CN (N =23) | preMCI(N =20) | aMCI(N = 76) | Dementia (N = 16) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72 +/− 4.38 | 74 +/− 5.15 | 75 +/− 6.83 | 76 +/− 6.66 |

| Years of Education | 15 +/− 3.28 | 16 +/− 3.32 | 14 +/− 3.42 | 16 +/− 2.78 |

| Primary Language (E/S/Other) | 10/13/0 | 11/7/2 | 32/41/3 | 7/7/2 |

| Genderof Participant(M/F) | 8/15 | 7/13 | 31/45 | 8/8 |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall | 7.35 +/− 3.06 | 6.53 +/− 4.48 | 1.96 +/− 2.81 | 0.31 +/− 1.25 |

| NACC-DR Delayed Recall | 11.43 +/− 3.80 | 11.85 +/− 4.34 | 7.40 +/− 4.07 | 2.53 +/− 3.54 |

| ORDT-DO % Accuracy | 86.5% +/− 8.04 | 78.0% +/− 15.93 | 68.03% +/− 17.28 | 60.63% +/− 17.02 |

| ORDT-DO Median RT | 2.81 +/− 0.62 | 3.07 +/− 0.81 | 3.19 +/− 0.64 | 3.53 +/− 0.83 |

Exclusion criteria included: (1) sensory loss or motor impairments significant enough to interfere with the participant’s ability to complete a battery of neuropsychological tests; (2) previous stroke or other unrelated neurological disorder known to affect cognition (i.e. moderate-severe Traumatic Brain Injury, seizure disorder, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, etc.); (3) current or past history of major psychiatric disturbance with hospitalization, active psychosis, bipolar disorder, current major depressive episode, or current or past history of alcohol or substance abuse within the six months prior to the first appointment; and (4) use of medications with anticholinergic properties (i.e. antipsychotics, sedatives, etc.).

Clinical Evaluation

As part of their participation in the Clinical Core at the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, each participant completed thorough clinical testing which included a physical and neurological exam performed by an experienced bilingual geriatric psychiatrist. Additionally, participants and their informants underwent a comprehensive interview designed to provide information sufficient for completing the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale (Rockwood, Strang, MacKnight, Downer, & Morris, 2000). Clinicians performing these evaluations were blinded to the participant’s neuropsychological test scores. Additional assessments, the results of which are not reported here, included the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center neuropsychological battery, and, whenever possible, neuroimaging studies including MRI and amyloid PET scans.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Participants were administered standardized memory measures, such as the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R; (Benedict, Schretlen, Groninger, & Brandt, 2010) and the NACC Delayed Paragraph Recall subtest (NACC-DR; (Elwood, 1991). Additional tests included the Trail Making Test (Tombaugh, 2004), Category Fluency (animals, fruits, and vegetables; (Loonstra, Tarlow, & Sellers, 2001), letter fluency (Lezak, Howieson, Loring, & Fischer, 2004) as well as WAIS-R Block Design (Snow, Tierney, Zorzitto, Fisher, & Reid, 1989) and Digit Span of the NACC UDS (Weintraub et al., 2009). As discussed below, age- and education-corrected delayed recall scores for the memory measures were used in determining final diagnosis.

Spanish language testing with equivalent standardized neuropsychological tests was completed for primary Spanish speakers. Primary language was determined by ascertaining the language the participant uses most often, feels more comfortable speaking, and used in completing the majority of their education. Tests given for primary Spanish speakers had appropriate age, education, and cultural/language normative data for the translated version. Testing was performed by proficient Spanish/English psychometricians.

Diagnostic Criteria

Participant diagnosis utilized the following criteria as well as NACC UDS criteria, with final diagnostic decisions being made by consensus diagnosis (see Table II)

Table II: Algorithmic diagnostic criteria.

Participant diagnosis was determined following completion of thorough clinical testing which included a physical and neurological exam performed by an experienced bilingual geriatric psychiatrist. Additionally, participants and their informants underwent a comprehensive interview designed to provide information sufficient for completing the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) scale. Clinicians performing these evaluations were blinded to neuropsychological test scores. Additional assessments, the results of which are not reported here, included the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center neuropsychological battery.

| Cognitively Normal | preMCI-Clinical | preMCI-Neuropsychological | aMCI | Dementia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory complaint? | X | ✓ | X | ✓ | ✓ |

| MMSE | ≥26 | ≥24 | ≥24 | ≥24 | ≥18 |

| Global CDR | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Delayed Recall (HVLT-R, LM- 1D) | ≤ 1.0 SD below normal | ≤ 1.0 SD below normal | ≥ 1.5 SD below normal one or both | ≥ 1.5 SD below normal | ≥ 2.0 SD below normal |

| Other Cognitive Domains | No scores ≤ −1.0 SD | No scores ≤ −1.0 SD | No scores ≤ −1.0 SD | No scores ≤ −1.0 SD | May be ≤ −1.5 SD |

| Functional Impairment | X | X | X | Some | ✓ |

| Major Neurocognitive Disorder | X | X | X | X | ✓ |

Cognitively Normal (CN):

(1) No subjective memory complaint evidenced from the participant or study partner; (2) MMSE score ≥ 26; (3) global Clinical Dementia rating (CDR) Scale of 0 [CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) = 0]; (4) scores less than 1 SD below expected levels on measures of delayed recall of the HVLT-R and NACC memory for passages based on appropriate age, educational, and cultural norms; (5) no reported functional impairment in independent activities of daily living by the participant or study partner; (6) does not meet Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) criteria for Minor or Major Neurocognitive Disorder; and (7) no scores less than −1 SD on any other neuropsychological test.

PreMCI-Clinical (Loewenstein et al., 2012):

(1) Evidence of subjective memory complaint and cognitive decline verified by study partner (2) MMSE ≥ 24; (3) global Clinical Dementia rating (CDR) Scale of 0.5 (CDR-SB = 0.5 – 2.0); (4) no neuropsychological impairment on measures of delayed recall of the HVLT-R and NACC memory for passages as specified in the criteria for the CN group; (5) no significant functional impairment in independent activities of daily living by the participant or study partner; (6) does not meet DSM-V criteria for Minor or Major Neurocognitive Disorder; and (7) no scores ≤ −1 SD on any other neuropsychological test.

PreMCI-Neuropsychological (Loewenstein et al., 2012):

(1) No evidence of subjective memory or cognitive decline after an extensive interview with the participant and the collateral informant; (2) MMSE score ≥ 24; (3) global Clinical Dementia rating (CDR) Scale of 0.0 (CDR-SB = 0); (4) scores −1.5 SD or below on measures of delayed recall of the HVLT-R and/or NACC memory for passages; (5) no significant functional impairment in independent activities of daily living; (6) does not meet DSM-V criteria for Minor or Major Neurocognitive Disorder

In the current study, the two PreMCI groups were combined for analysis, based on previous results indicating that the two groups had equivalent risk of progression to impairment (Loewenstein et al., 2012).

Amnestic MCI (aMCI):

(1) Evidence of subjective memory complaint verified by study partner (2) MMSE score ≥ 24; (3) global Clinical Dementia rating (CDR) Scale of 0.5 (0.5 < CDR-SB < 4); (4) scores −1.5 SD or below on measures of delayed recall of the HVLT-R and NACC memory for passages; (5) no significant functional impairment; (6) does not meet DSM-V criteria for Major Neurocognitive Disorder.

Dementia:

(1) Evidence of subjective memory complaint verified by study partner (2) MMSE score ≥ 18; (3) global Clinical Dementia rating (CDR) Scale of 1.0 (CDR-SB > 4); (4) scores 2 SD or more below expected levels on measures of delayed recall of the HVLT-R and NACC memory for passages; (5) significant functional impairment in activities of daily living; (6) meets DSM-V criteria for Major Neurocognitive Disorder; and (7) other neuropsychological scores may be 1.5 SD or more below expected levels.

Object Recognition and Discrimination Task

The Object Recognition and Discrimination Task (ORDT) was adapted from a visual discrimination (“oddity”) task used by Devlin and Price (Devlin & Price, 2007). Original stimuli were obtained with permission from the authors and were presented on a laptop or desktop computer using E-Prime software (Psychology Software Tools).

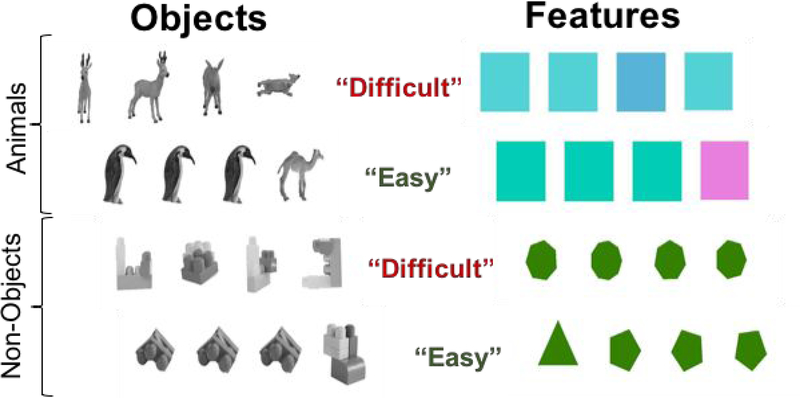

Sample stimuli from the ORDT are presented in Figure I. On each trial, participants were shown a horizontal array of four stimuli (Non-Objects, Shapes, Colors, Animals). Non-objects were photographs of models created from building blocks, resulting in entities that were not found in the real world. On each trial, three of the stimuli depicted the same object or entity, while the fourth stimulus was a different object/entity. The participant was asked to identify the different stimulus (the “target”) as quickly and as accurately as possible. Trial conditions included object type and difficulty level (Easy, Difficult). Trial difficulty and object type were varied throughout the test, such that the trial conditions were interspersed randomly within the stimulus train. In the “easy” condition, the three non-target stimuli were all presented in the same orientation. In the “difficult” condition, the three non-target stimuli are rotated individually (horizontally or vertically) in picture plane. In this way, success on the “difficult” condition requires the participant to recognize that the three non-target stimuli are the same entity even though their appearance is changed by rotation. This study reports performance on the “Difficult Objects” trials only (Difficult Animals and Difficult Non-Objects), since it was this condition that was specifically associated with bilateral perirhinal cortex activation in Devlin & Price’s original study (Devlin & Price, 2007). The decision to combine difficult objects trials was further supported by non-significant findings described in the Results section. Responses, as well as latency and accuracy of response, were logged with E-Prime software.

Figure I: Representation of Standard Trials of the Object Recognition and Discrimination Task.

On each trial, participants were shown a horizontal array of four stimuli (Non-Objects, Shapes, Colors, Animals). Non-objects were photographs of models created from building blocks, resulting in entities that were not found in the real world. Task conditions included object type and difficulty level (Easy, Difficult). In the “easy” condition, the three non-target items were all presented in the same orientation. In the “difficult” condition, the three non-target items are rotated individually (horizontally or vertically) in picture plane. In this way, success on the “difficult” condition requires the participant to recognize that the three non-target items are the same entity even though their appearance is changed by rotation.

The Introduction and Practice phase consisted of visually-presented instructions that were also spoken aloud by the test administrator. Then, the task began with 16 “easy” practice trials drawn from the stimulus sets described above. Participants had unlimited time to complete these trials.

The experimental task consisted of 40 trials in each test condition, presented for 6 seconds with a 1-second inter-trial interval. Stimuli for each trial remained on the screen for six seconds or until a participant response was recorded.

Analysis

Parametric analyses of variance were used to determine if there were significant group differences in age and years of education. Pearson chi-square tests were employed to determine if there were significant group differences in primary language and gender of participants between diagnostic subgroups.

Prior to completing the proposed analyses involving both the difficult animal and difficult non-object conditions in one score, a repeated- measures ANOVA was completed with Log-transformed, standardized versions (Z) of accuracy scores for each condition, separately. If no statistical difference was determined, then the conditions would be combined as was initially intended and shown in the original study (ORDT-DO; Devlin & Price, 2007). Diagnostic subgroup was included as a between-subjects factor and interaction term.

Following these analyses and combination of the ‘difficult objects’ trials, additional two-way ANOVAs were completed to assess the effect of primary language and gender on ORDT-DO performance, as well as interaction effects of either of these variables and diagnostic subgroup on ORDT-DO performance. An ANOVA was also completed to determine whether there were significant group mean differences in median reaction time on correct trials of the ORDT-DO across diagnostic subgroups.

We found unequal sample variance estimates across groups for the HVLT-R and ORDT-DO. Because of this, log-transformed standardized versions (Z) of the HVLT-R, NACC-DR, and ORDT-DO were used to determine if there were group differences in task performance related to clinical diagnosis. Following significant omnibus test findings, Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons were performed in order to elucidate specific group mean differences. Non-transformed means (M) and standard deviations (SD) were reported and presented graphically for ease of interpretability. Independent samples t-tests were also performed with these transformed Z-scores to determine differences in task performance between participants in the CN and PreMCI groups. Additionally, because the average of the delayed recall score on one of the standard memory tests (HVLT-R) suggested floor performance of the dementia group, all analyses of variance and chi-square tests were completed again, excluding the dementia group, to ensure that previously obtained relationships were preserved. Further analyses of demographic and neuropsychological variables were also completed for the PreMCI group separated into its subgroups (PreMCI-Clinical, PreMCI-Neuropsychological) in order to determine if these subgroups evidenced significant group mean differences that would merit their separation in future analyses.

A multinomial logistic regression was performed to determine whether task performance contributed to prediction of diagnostic group membership. The dependent variable was diagnostic subgroup, and all groups except the dementia group were included due to the aforementioned floor effect of the HVLT-R. The cognitively normal group was the reference category. Independent variables for the first version of this analysis included the transformed, standardized version (Z) of the HVLT-R, NACC-DR, and the ORDT-DO. A version of this analysis was also completed that included age and years of education as covariates due to the known relationship between both variables and memory and cognitive task performance in older adults.

P-values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the original 143 participants who were screened for task participation, eight participants were unable to complete the ORDT due to cognitive impairment (N = 4), visual impairment (N = 1), refusal to participate (N = 1), and computer error (N = 2). Overall, one hundred thirty-five participants were included in the final analyses (Table I; CN: N = 23; PreMCI: N = 20; aMCI: N = 76; Dementia: N = 16). Age of participants ranged from 65 to 97 years. Participant education ranged from 4 years to 20 years. No significant group differences were found in average age, years of education, primary language, or gender (Age: F[3,129] = 1.80, p = 0.15; Education: F[3,133] = 2.04, p = 0.11; Primary Language: X2[3] = 1.90, p = 0.59; Gender: X2[3] = 1.16, p = 0.76). There were more English speakers than Spanish speakers in each group and there were variable ratios of males to females.

Additional analyses indicate that the average scores of each diagnostic subgroup on the HVLT-R and NACC-DR mirror age-matched decline across diagnostic subgroups with increasing amnestic impairment, suggesting that findings from the following analysis most likely reflect normative performance of these populations.

ORDT-specific Analyses

First, analyses were completed to determine whether there were significant differences between ‘difficult non-objects’ and ‘difficult animals’ conditions on the ORDT. There was not a main effect of task condition (F[1,131] = 0.79, p = 0.37) or an interaction between task condition and diagnostic subgroup (F[3,131] = 0.37, p = 0.77). Therefore, a single “difficult objects” performance score (ORDT-DO) was used in subsequent analyses.

In terms of primary language, there was not a main effect of primary language or an interaction effect of primary language and diagnostic subgroup on ORDT-DO performance (F[1,120] = 0.06, p = 0.81; F[3,120] = 0.65, p = 0.56). In terms of participant gender, there was not a main effect of gender or an interaction effect of gender and diagnostic subgroup on ORDT-DO performance (F[1,127] = 0.07, p = 0.79; F[3,127] = 0.15, p = 0.93).

There was a significant difference in median reaction time for correct trials of the ORDT-DO across diagnostic subgroups (F[3,134] = 3.70, p = 0.01, ηp2 = 0.08). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed group mean differences between only the CN and dementia groups (CN: M = 2.81 seconds, SD = 0.62; Dementia: M = 3.53 seconds, SD = 0.83).

Group Differences

As would be expected due to the inclusion of traditional measures in defining diagnostic subgroups (incorporation bias; Weissberger et al., 2017), there were statistically significant differences between diagnostic subgroups in performance on both traditional memory measures, as well as the ORDT-DO (Figure II; HVLT-R: F[3,131] = 28.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.40; NACC-DR: F[3,133] = 25.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.37; ORDT-DO: F[3,134] = 8.74, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.17). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed group mean differences between the CN and the aMCI and dementia groups [HVLT-R (CN: M = 7.35, SD = 3.06; aMCI: M = 1.96, SD = 2.81; Dementia: M = 0.31, SD = 1.25); NACC-DR (CN: M = 11.43, SD = 3.80; aMCI: M = 7.40, SD = 4.07; Dementia: M = 2.53, SD = 3.54); ORDT-DO (CN: M = 86.5, SD = 8.04; aMCI: M = 68.03, SD = 17.28; Dementia: M = 60.63, SD = 17.02)]. Importantly, when an independent samples t-test was performed comparing the CN and PreMCI groups, only the ORDT-DO revealed significant group mean difference in test scores (t[23.93] = 2.18, p = 0.04, Cohen’s d = 0.61). The traditional neuropsychological measures failed to discriminate between these two groups, as would be expected based on diagnostic criteria for these subgroups (NACC-DR: t[41] = 0.43, p = 0.93; HVLT-R: t[28.29] = 1.33, p = 0.20).

Figure II: Graphical Representation of Performance of Clinical Diagnostic Subgroups Compared to the Cognitively Normal Group on Traditional Memory Measures and the Object Recognition and Discrimination Task.

There were statistically significant differences between diagnostic subgroups in performance on both traditional memory measures, and also the ORDT-DO (HVLT-R: F[3,131] = 28.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.40; NACC-DR: F[3,133] = 25.95, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.37; ORDT-DO: F[3,134] = 8.74, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.17). Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction revealed group mean differences between the CN and the aMCI and dementia groups [HVLT-R (CN: M = 7.35, SD = 3.06; aMCI: M = 1.96, SD = 2.81; Dementia: M = 0.31, SD = 1.25); NACC-DR (CN: M = 11.43, SD = 3.80; aMCI: M = 7.40, SD = 4.07; Dementia: M = 2.53, SD = 3.54); ORDT-DO (CN: M = 86.5, SD = 8.04; aMCI: M = 68.03, SD = 17.28; Dementia: M = 60.63, SD = 17.02)]. Importantly, when an independent samples t-test was performed comparing the CN and PreMCI groups, only the ORDT-DO revealed significant group mean difference in test scores (t[23.93] = 2.18, p = 0.04, Cohen’s d = 0.61). The traditional neuropsychological measures failed to discriminate between these two groups, as would be expected based on diagnostic criteria (NACC-DR: t[41] = 0.43, p = 0.93; HVLT-R: t[28.29] = 1.33, p = 0.20). CN = Cognitively Normal; PreMCI = pre- Mild Cognitive Impairment; aMCI = amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment; NACC Delayed Paragraph Recall (NACC-DR); Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R); Object Recognition and Discrimination Task Difficult Objects Trials (ORDT-DO). NOTE: Standard non-transformed scores compared to the cognitively normal group are presented, error bars equivalent to standard error of the mean.

When the dementia group was removed and previous analyses were rerun, all relationships were preserved.

Analyses of the PreMCI group revealed that 11 participants met criteria for PreMCI-Clinical (N = 11) and 9 participants met criteria for PreMCI-Neuropsychological (N = 9; Table III). There were no significant differences between the PreMCI subgroups in terms of primary language or gender of participants (Primary Language: X2[1] = 0.08, p = 0.78; Gender: X2[1] = 0.02, p = 0.89). Additionally, there were no significant differences between the PreMCI subgroups in terms of age or years of education (Age: F[1,18] = 0.03, p = 0.86; Years of Education: F[1,18] = 0.001, p = 0.97). Comparisons of the PreMCI subgroups across test variables revealed no significant group mean differences (ORDT-DO: F[1,19] = 0.10, p = 0.75; ORDT-DO Reaction Time Correct Trials: F[1,19] = 0.08, p = 0.79; NACC-DR: F[1,19] = 0.33, p = 0.58), although the difference between these subgroups on the HVLT-R trended toward significant (HVLT-R: F[1,18] = 3.91, p = 0.06). Taken together, these findings justified combining the PreMCI subgroups in subsequent analyses.

Table III: PreMCI subgroup specific demographic information.

PreMCI subgroup specific demographic information illustrated for all PreMCI participants. As is illustrated by the p-values included, there were no significant differences found between the PreMCI subgroups in terms of primary language, gender of participants, age, or years of education. Comparisons of the PreMCI subgroups across test variables also revealed no significant group mean differences, although the difference between these subgroups on the HVLT-R trended toward significant. PreMCI = pre-Mild Cognitive Impairment; E = English; S = Spanish; M = Male; F = Female; RT= Reaction Time. NOTE: Error terms included are standard deviation.

| PreMCI-Clinical (N = 11) | PreMCI-Neuropsychological (N = 9) | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 74 +/− 5.70 | 74 +/− 4.66 | 0.86 |

| Years of Education | 16 +/− 3.82 | 16 +/− 2.75 | 0.97 |

| Primary Language (E/S/Other) | 7/4/0 | 4/3/2 | 0.78 |

| Gender of Participant(M/F) | 4/7 | 3/6 | 0.89 |

| HVLT-R Delayed Recall | 8.40 +/− 3.50 | 4.44 +/− 4.69 | 0.06 |

| NACC-DR Delayed Recall | 12.18 +/− 4.22 | 11.44 +/− 4.72 | 0.58 |

| ORDT-DO % Accuracy | 78.64% +/− 14.33 | 77.22% +/− 18.56 | 0.75 |

| ORDT-DO Median RT | 3.12 +/− 0.88 | 3.02 +/− 0.75 | 0.79 |

Multinomial Regression

The first model included performance variables of the two traditional memory measures and the ORDT-DO. According to the model fitting information, the final model was statistically significant (X2[6] = 69.69, p < 0.001). Neither Pearson nor Deviance Chi-Square tests were significant, which also supports the goodness fit of the model (Pearson: X2[214] = 218.67, p = 0.40; Deviance: X2[214] = 140.02, p = 1.00). According to the tests of likelihood ratios, the traditional memory measures contributed to prediction of current diagnosis over the reduced model (HVLT-R: X2[2] = 18.60, p < 0.001; NACC-DR: X2[2] = 8.27, p = 0.02). The model, which includes all three measures, represented a significant increase in classification accuracy over accuracy achieved by chance alone (Classification Accuracy = 75.0%). The ORDT-DO was also a statistically significant predictor in the model (X2[2] = 15.92, p < 0.001).

According to the parameter estimates, only the ORDT-DO contributed to prediction of current PreMCI group membership compared to the CN group (Wald[1] = 5.26, p = 0.02, Exp(B) = 0.60). This finding suggests that, given a one-unit increase in standardized ORDT-DO score, there is a 40% reduction in the odds of a participant being identified in the PreMCI group when other variables in the model are held constant.

When predicting current aMCI group membership over CN group membership, HVLT-R and ORDT-DO were both significant (HVLT-R Wald[1] = 10.87, p < 0.001, Exp(B) = 0.45; ORDT-DO: Wald[1] = 9.52, p = 0.002, Exp(B) = 0.50), while NACC-DR was not significant (NACC-DR: Wald[1] = 2.77, p = 0.10)

When including age and education, the final model was statistically significant (X2[10] = 72.12, p < 0.001). According to the tests of likelihood ratios, HVLT-R, NACC-DR, and ORDT-DO remained statistically significant predictors in the model. However, age, and years of education were not significant (Age: X2[2] = 0.37, p = 0.83; Years of Education: X2[2] = 1.32, p = 0.52), suggesting that these variables did not provide unique contributions to the model. Therefore, this model was not considered in final discussion.

Discussion

Although traditional memory measures are sufficiently sensitive to general memory impairments found in later stages of AD (Petersen et al., 1999; Bilgel et al., 2014), use of such “blunt” measures and diagnostic methods may lead to high rates of over- and under-diagnosis of MCI (Edmonds et al., 2015; Edmonds et al., 2016). The current study suggests that a novel measure of object discrimination that assesses a primary function of the perirhinal cortex (PRC) increased the correct identification of individuals with subtle cognitive impairment associated with risk of AD progression. Moreover, using visual tasks like the ORDT that employ less culturally- or educationally-dependent paradigms and stimuli allows for the creation of linguistically and culturally valid normative scores, which is increasingly important as the older adult population in the US rapidly diversifies (Snyder et al., 2014). As the ORDT has in the current study, visual discrimination tasks have been investigated in international populations for the detection of early impairment related to MCI (Alegret et al., 2009).

Notably, the PRC has also been shown to be vulnerable to age-related physiological changes (Burke et al., in press; Burke et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2017; Maurer, Burke, Diba, & Barnes, 2017; Moyer, Furtak, McGann, & Brown, 2011). These changes have been shown to affect object discrimination performance in both animals (Gaynor et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2017) and humans (Ryan et al., 2012; Yeung et al., 2013). Because of this, it will be important to pursue further refinements of functionally specific tasks that are differentially sensitive to normal and pathological aging. The results of the current study provide an initial step in this regard, since the ORDT was able to differentiate the performance of cognitively normal older adults from those with PreMCI, aMCI, and dementia. These findings are similar to those found by Barense and colleagues (2012) who identified deficits in discrimination of high ambiguity objects within high interference stimulus trains in patients with medial temporal lobe damage including the perirhinal cortex. Although our study only considered performance on the target condition, target trials were interspersed in the stimulus train with both low and high ambiguity stimuli, suggesting that the declining performance of our participant groups with greater predicted medial temporal lobe dysfunction on target trials is at least partially related to the presence of highly interfering stimuli throughout the test.

Notably, we did not identify significant differences in ORDT-DO performance between PreMCI group participants that met criteria for either PreMCI-Neuropsychological or PreMCI-Clinical, suggesting that ORDT-DO deficits are present in PreMCI with or without impaired performance on traditional memory measures. The even ratio of PreMCI-Neuropsychological and PreMCI-Clinical participants most likely impacted the calculated average performance of this group on traditional memory measures. However, we did not identify significant differences in the performance of these groups on traditional memory measures, although there was one trend toward significance that suggested the PreMCI-Neuropsychological group performed worse on the HVLT-R compared to the PreMCI-Clinical group. The current sample is not large enough to have power to investigate these diagnostic groups separately. In future studies, when we have accrued a larger group of participants meeting criteria for PreMCI-Neuropsychological and PreMCI-Clinical, we will investigate these subgroups and their relationship to neuroimaging measures and risk of progression. We are most interested in investigating the ORDT-DO in identification of the PreMCI-Clinical subgroup, as we would like to examine whether the ORDT can detect cognitive impairment prior to traditional memory measures.

The utility of the ORDT in detecting very early cognitive change may depend on the presence of ‘typical’ pathological spread, starting in the transentorhinal cortex and affecting the hippocampus and its efferent targets (Kurylo et al., 1996). If true, this would suggest that the ORDT would show less early sensitivity to onset of non-AD pathology or AD pathology that begins atypically in other brain regions. Performance on the ORDT is currently being evaluated in our laboratory in the context of structural and functional neuroimaging data on these participants in order to determine if ‘typical’ disease progression is predictive of ORDT task performance.

Unfortunately, measures such as structural MRI volumes or cortical thickness may show minimal changes in the PreMCI state (Duara et al., 2013). Specifically, cognitive aging studies support the presence of functional neurophysiological change prior to pathological neurodegeneration in older adults exhibiting cognitive impairment (Burke & Barnes, 2006). This suggests the need for considering other measures of the integrity of the functional brain connectome such as fMRI, amyloid or tau PET (Brooks & Loewenstein, 2010). It will be particularly important to determine how connections of the PRC to other task-relevant structures affects ORDT performance. For example, because “difficult” discriminations are achieved by rotation of non-target stimuli, it is possible that posterior parietal cortex, which has reciprocal connections with the PRC and medial temporal lobe, also supports task completion (Harris et al., 2018). If this is true, the ORDT-DO may be capturing the combined insult of both early pathological tau and amyloid plaque accumulation, supporting its impressive sensitivity to the earliest brain changes related to AD. However, as was mentioned previously, the PRC has been shown to support identification of same stimuli presented at different viewpoints, and may be primarily involved in ORDT-DO task performance as was suggested by Devlin and Price in their original study (2007). Other structures that likely contribute to object recognition and discrimination abilities include the hippocampus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex.

A potential weakness of the study is that primary analyses involved assessing the ORDT-DO against traditional memory measures in identification of significant differences between diagnostic subgroups. These traditional memory measures were used for constructing diagnostic subgroups, which would be assumed to give them an advantage in predicting group differences. In fact, the ORDT was also able to identify differences between the CN group and both the dementia and aMCI groups, as well as the identification of PreMCI group membership compared to CN group membership, when controlling for all other measures. Thus, findings from the current study support the superiority of the ORDT in comparison to traditional memory measures in identifying individuals with subtle cognitive decline.

Another important limitation to consider in the current study is that it is cross-sectional, so the object discrimination deficits were evaluated across individuals at only one-time point. Since the data reported here are part of a longitudinal study, follow-up evaluation of these participants is ongoing and will allow us to determine whether ORDT performance predicts case-wise longitudinal decline in performance over time and, specifically, progression to clinical Alzheimer’s disease (verified by amyloid PET and, where available, autopsy).

Although the study supports the use of an object discrimination task as an independent measure of early cognitive impairment related to AD, performing well alongside traditional memory measures actually used in the diagnostic process, accurate diagnosis or prediction of cognitive decline will likely not be provided by any single measure of performance, anatomy, or pathology. Creating a composite medial temporal lobe functioning score, in which performance data is combined with pre-mortem measures of AD structural changes and pathology may emerge as the most useful approach to identifying incipient impairment (Schneider et al., 2014). The success of such a composite depends on identifying the most sensitive and process-specific cognitive measures available. This is especially important in determining the true underlying pathology of individuals in the current study diagnosed as PreMCI or aMCI. Future studies will employ the ORDT as well as other cognitive, anatomical, and pathological measures of early impairment [i.e., recovery from proactive semantic interference (Loewenstein et al., 2018; Loewenstein et al., 2016), volumetric measures of temporal lobe anatomy, PRC thinning and amyloid load]. Employing a composite score will refine our ability to provide early detection of those patients at risk for development of AD, thus expanding opportunities for targeted therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgements

Funding Sources

This research is supported by the efforts of Kevin Hanson, Luz Arazo, and other members of the 1Florida ADRC Project II research coordinator and psychometrician staff. This work was supported by the 1Florida Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (National Institute on Aging Grants; grant number 5 P50 AG047726602), the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute (grant number NCATS UL1TR001427), and by grant number 1 R01 AG047649-01A1 to D.A.L.

Footnotes

Conflicts

None of the Authors have conflict of interest involving this manuscript.

Citations

- Alegret M, Boada-Rovira M, Vinyes-Junque G, Valero S, Espinosa A, Hernandez I, … Tarraga L (2009). Detection of visuoperceptual deficits in preclinical and mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 31(7), 860–867. Retrieved from 10.1080/13803390802595568. doi: 10.1080/13803390802595568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Henson RN, Lee AC, & Graham KS (2010). Medial temporal lobe activity during complex discrimination of faces, objects, and scenes: Effects of viewpoint. Hippocampus, 20(3), 389–401. Retrieved from 10.1002/hipo.20641. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barense MD, Ngo JK, Hung LH, & Peterson MA (2012). Interactions of memory and perception in amnesia: the figure-ground perspective. Cereb Cortex, 22(11), 2680–2691. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22172579. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartko SJ, Winters BD, Cowell RA, Saksida LM, & Bussey TJ (2007). Perirhinal cortex resolves feature ambiguity in configural object recognition and perceptual oddity tasks. Learn Mem, 14(12), 821–832. Retrieved from 10.1101/lm.749207. doi: 10.1101/lm.749207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, & Brandt J (2010). Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised: Normative Data and Analysis of Inter-Form and Test-Retest Reliability http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/clin.12.1.43.1726 . Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/clin.12.1.43.1726https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1076/clin.12.1.43.1726. Retrieved from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1076/clin.12.1.43.1726. doi:The Clinical Neuropsychologist, February 1998, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 43–55 [Google Scholar]

- Bilgel M, An Y, Lang A, Prince J, Ferrucci L, Jedynak B, & Resnick SM (2014). Trajectories of Alzheimer disease-related cognitive measures in a longitudinal sample. Alzheimers Dement, 10(6), 735–742.e734. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.520. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, & Braak E (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol, 82(4), 239–259. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks LG, & Loewenstein DA (2010). Assessing the progression of mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: current trends and future directions. Alzheimers Res Ther, 2(5), 28 Retrieved from 10.1186/alzrt52. doi: 10.1186/alzrt52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MJ, Booth MC, Rolls ET, & Gaffan D (2001). Selective perceptual impairments after perirhinal cortex ablation. J Neurosci, 21(24), 9824–9836. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MJ, & Gaffan D (1997). Impairment of visual object-discrimination learning after perirhinal cortex ablation. Behav Neurosci, 111(3), 467–475. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=9189261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, & Barnes CA (2006). Neural plasticity in the ageing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci, 7(1), 30–40. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16371948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke SN, Maurer AP, Nematollahi S, Uprety A, Wallace JL, & Barnes CA (in press). Advanced age dissociates dual functions of the perirhinal cortex. Journal of Neuoscience, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Burke SN, Wallace JL, Hartzell AL, Nematollahi S, Plange K, & Barnes CA (2011). Age-Associated Deficits in Pattern Separation Functions of the Perirhinal Cortex: A Cross-species Consensus. Behavioral Neuroscience, 125(6), 836–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, & Murray EA (2003). Impairments in visual discrimination after perirhinal cortex lesions: testing ‘declarative’ vs. ‘perceptual-mnemonic’ views of perirhinal cortex function. Eur J Neurosci, 17(3), 649–660. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=12581183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli RJ, Locke DE, Dueck AC, Knopman DS, Woodruff BK, Hoffman-Snyder C, … Reiman EM (2014). The neuropsychology of normal aging and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 10(1), 84–92. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowell RA, Bussey TJ, & Saksida LM (2006). Why does brain damage impair memory? A connectionist model of object recognition memory in perirhinal cortex. J Neurosci, 26(47), 12186–12197. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17122043. doi:26/47/12186 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2818-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, & Price CJ (2007). Perirhinal contributions to human visual perception. Curr Biol, 17(17), 1484–1488. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.066. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Greig MT, Potter E, Barker W, Raj A, … Potter H (2011). Pre-MCI and MCI: neuropsychological, clinical, and imaging features and progression rates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 19(11), 951–960. Retrieved from 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107c69. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182107c69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Shen Q, Barker W, Potter E, Varon D, … Buckley C (2013). Amyloid positron emission tomography with (18)F-flutemetamol and structural magnetic resonance imaging in the classification of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 9(3), 295–301. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Clark LR, Jak AJ, Nation DA, McDonald CR, …Bondi MW (2015). Susceptibility of the conventional criteria for mild cognitive impairment to false-positive diagnostic errors. Alzheimers Dement, 11(4), 415–424. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.005. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Jak AJ, Galasko DR, Salmon DP, & Bondi MW (2016). “Missed” Mild Cognitive Impairment: High False-Negative Error Rate Based on Conventional Diagnostic Criteria. J Alzheimers Dis, 52(2), 685–691. Retrieved from 10.3233/jad-150986. doi: 10.3233/jad-150986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood RW (1991). The Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised: psychometric characteristics and clinical application. Neuropsychol Rev, 2(2), 179–201. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo CO, Changoor AT, Page-Gould E, Lee AC, & Barense MD (2016). Early cognitive decline in older adults better predicts object than scene recognition performance. Hippocampus, 26(12), 1579–1592. Retrieved from 10.1002/hipo.22658. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor LS, Johnson SA, Mizell JM, Campos KT, Maurer AP, Bauer RM, & Burke SN (2018). Impaired Discrimination with Intact Crossmodal Association in Aged Rats: A Dissociation of Perirhinal Cortical-Dependent Behaviors. In (Vol. 132, pp. 138–151): Behavioral Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris IM, Egan GF, Sonkkila C, Tochon-Danguy HJ, Paxinos G, & Watson JDG (2018). Selective right parietal lobe activation during mental rotationA parametric PET study. Brain, 123(1), 65–73. Retrieved from https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-pdf/123/1/65/17874280/1230065.pdf. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.1.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber CM, Yee C, May T, Dhanala A, & Mitchell CS (2017). Cognitive Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease: Amyloid-Beta versus Tauopathy. J Alzheimers Dis Retrieved from 10.3233/jad-170490. doi: 10.3233/jad-170490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson SA, Sacks PK, Turner SM, Gaynor LS, Ormerod BK, Maurer AP, … Burke SN (2016). Discrimination performance in aging is vulnerable to interference and dissociable from spatial memory. In Learn Mem (Vol. 23, pp. 339–348). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SA, Turner SM, Santacroce LA, Carty KN, Shafiq L, Bizon JL, … Burke SN (2017). Rodent age-related impairments in discriminating perceptually similar objects parallel those observed in humans. Hippocampus, 27(7), 759–776. Retrieved from 10.1002/hipo.22729. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan UA, Liu L, Provenzano FA, Berman DE, Profaci CP, Sloan R, … Small SA (2014). Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci, 17(2), 304–311. Retrieved from 10.1038/nn.3606. doi: 10.1038/nn.3606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivisaari SL, Tyler LK, Monsch AU, & Taylor KI (2012). Medial perirhinal cortex disambiguates confusable objects. Brain, 135(Pt 12), 3757–3769. Retrieved from 10.1093/brain/aws277. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger KR, Lam CS, & Wilson RS (2006). The Word Accentuation Test - Chicago. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 28(7), 1201–1207. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. doi: 10.1080/13803390500346603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumm S, Kivisaari SL, Probst A, Monsch AU, Reinhardt J, Ulmer S, … Taylor KI (2016). Cortical thinning of parahippocampal subregions in very early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging, 38, 188–196. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.001. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurylo DD, Corkin S, Rizzo JF Iii, & Growdon JH (1996). Greater relative impairment of object recognition than of visuospatial abilities in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology, 10(1), 74–81. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.10.1.74 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AC, Barense MD, & Graham KS (2005). The contribution of the human medial temporal lobe to perception: bridging the gap between animal and human studies. Q J Exp Psychol B, 58(3–4), 300–325. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16194971. doi:M507323452325H62 [pii] 10.1080/02724990444000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW, & Fischer JS (2004). Neuropsychological assessment USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, DeKosky S, Bauer RM, Rosselli M, Guinjoan SM, … Duara R (2018). Utilizing semantic intrusions to identify amyloid positivity in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology, 91(10), e976–e984. Retrieved from 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006128. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000006128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Curiel RE, Greig MT, Bauer RM, Rosado M, Bowers D, … Duara R (2016). A Novel Cognitive Stress Test for the Detection of Preclinical Alzheimer Disease: Discriminative Properties and Relation to Amyloid Load. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 24(10), 804–813. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.02.056. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.02.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein DA, Greig MT, Schinka JA, Barker W, Shen Q, Potter E, … Duara R (2012). An investigation of PreMCI: subtypes and longitudinal outcomes. Alzheimers Dement, 8(3), 172–179. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.002. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loonstra AS, Tarlow AR, & Sellers AH (2001). COWAT metanorms across age, education, and gender. Appl Neuropsychol, 8(3), 161–166. Retrieved from 10.1207/s15324826an0803_5. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an0803_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason EJ, Hussey EP, Molitor RJ, Ko PC, Donahue MJ, & Ally BA (2017). Family History of Alzheimer’s Disease is Associated with Impaired Perceptual Discrimination of Novel Objects. J Alzheimers Dis, 57(3), 735–745. Retrieved from 10.3233/jad-160772. doi: 10.3233/jad-160772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer AP, Burke SN, Diba K, & Barnes CA (2017). Attenuated Activity across Multiple Cell Types and Reduced Monosynaptic Connectivity in the Aged Perirhinal Cortex. J Neurosci, 37(37), 8965–8974. Retrieved from 10.1523/jneurosci.0531-17.2017. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0531-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer JR Jr., Furtak SC, McGann JP, & Brown TH (2011). Aging-related changes in calcium-binding proteins in rat perirhinal cortex. Neurobiol Aging, 32(9), 1693–1706. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.10.001. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, & Bussey TJ (1999). Perceptual-mnemonic functions of the perirhinal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci, 3(4), 142–151. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome RN, Duarte A, & Barense MD (2012). Reducing perceptual interference improves visual discrimination in mild cognitive impairment: implications for a model of perirhinal cortex function. Hippocampus, 22(10), 1990–1999. Retrieved from 10.1002/hipo.22071. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, & Kokmen E (1999). Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol, 56(3), 303–308. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu WY, Yang Q, Zhang W, Wang N, Zhang D, Huang Y, & Ma C (2017). The Correlations Between Postmortem Brain Pathologies and Cognitive Dysfunction in Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Alzheimer Res Retrieved from 10.2174/1567205014666171106150915. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666171106150915 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rockwood K, Strang D, MacKnight C, Downer R, & Morris JC (2000). Interrater reliability of the Clinical Dementia Rating in a multicenter trial. J Am Geriatr Soc, 48(5), 558–559. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan L, Cardoza JA, Barense MD, Kawa KH, Wallentin-Flores J, Arnold WT, & Alexander GE (2012). Age-related impairment in a complex object discrimination task that engages perirhinal cortex. Hippocampus, 22(10), 1978–1989. Retrieved from 10.1002/hipo.22069. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N, Feldman H, Giacobini E, Jones R, … Kivipelto M (2014). Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med, 275(3), 251–283. Retrieved from 10.1111/joim.12191. doi: 10.1111/joim.12191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow WG, Tierney MC, Zorzitto ML, Fisher RH, & Reid DW (1989). WAIS-R test-retest reliability in a normal elderly sample. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol, 11(4), 423–428. Retrieved from 10.1080/01688638908400903. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder PJ, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Brannan S, Miller DS, Schindler RJ, DeSanti S, … Carrillo MC (2014). Assessing cognition and function in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: do we have the right tools? Alzheimers Dement, 10(6), 853–860. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.158. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone D, Imabayashi E, Maikusa N, Okamura N, Furumoto S, Kudo Y, … Matsuda H (2017). Regional tau deposition and subregion atrophy of medial temporal structures in early Alzheimer’s disease: A combined positron emission tomography/magnetic resonance imaging study. Alzheimers Dement (Amst), 9, 35–40. Retrieved from 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.07.001. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN (2004). Trail Making Test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 19(2), 203–214. Retrieved from 10.1016/s0887-6177(03)00039-8. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6177(03)00039-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, Ferris S, Graff-Radford NR, Chui H, … Morris JC (2009). The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): The Neuropsychological Test Battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord, 23(2), 91–101. Retrieved from 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberger GH, Strong JV, Stefanidis KB, Summers MJ, Bondi MW, & Stricker NH (2017). Diagnostic Accuracy of Memory Measures in Alzheimer’s Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol Rev, 27(4), 354–388. Retrieved from 10.1007/s11065-017-9360-6. doi: 10.1007/s11065-017-9360-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GS, & Robertson G (2006). Wide Range Achievement Test 4 professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources

- Woodcock RW, Muñoz-Sandoval AF, Ruef ML, & Alvarado CG (2005). Woodcock language proficiency battery--Revised Retrieved from Itasca, IL: [Google Scholar]

- Yeung LK, Ryan JD, Cowell RA, & Barense MD (2013). Recognition memory impairments caused by false recognition of novel objects. J Exp Psychol Gen, 142(4), 1384–1397. Retrieved from 10.1037/a0034021. doi: 10.1037/a0034021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]