Abstract

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) may reflect a dementia prodrome or modifiable risk factor such as sleep disturbance. What is the association between sleep and SCD? Cross-sectional design, from two studies of older adults: the WHICAP in the USA, and the HELIAD in Greece. 1576 WHICAP and 1456 HELIAD participants, without mild cognitive impairment, dementia, or severe depression/anxiety were included. Participants were mostly women, with 12 (WHICAP) and 8 (HELIAD) mean years of education. Sleep problems were estimated using the Sleep Scale from the Medical Outcomes Study. SCD was assessed using a structured complaint questionnaire that queries for subjective memory and other cognitive symptoms. Multinomial or logistic regression models were used to examine whether sleep problems were associated with complaints about general cognition, memory, naming, orientation, and calculations. Age, sex, education, sleep medication, use of medications affecting cognition, comorbidities, depression and anxiety were used as covariates. Objective cognition was also used estimated by summarizing neuropsychological performance into composite z-scores. Sleep problems were associated with two or more complaints; WHICAP:β=1.93(95%CI: 1.59–2.34),p≤0.0001, HELIAD:β=1.48(95%CI:1.20–1.83),(p≤0.0001). Sleep problems were associated with complaints in all the cognitive sub-categories except orientation for the WHICAP. The associations were noted regardless of objective cognition. At any given level of objective cognition, sleep disturbance is accompanied by subjective cognitive impairment. The replicability in two ethnically, genetically, and culturally different cohorts adds validity to our results. Results have implications for the correlates, and potential etiology of SCD, which should be considered in the assessment and treatment of older adults with cognitive complaints.

Keywords: sleep problems, subjective cognitive decline, elderly, healthy aging

Introduction

Sleep quality has been associated with objective cognitive performance in many studies, especially in the elderly population (Jaussent, Bouyer et al. 2012, Xu, Jiang et al. 2014, Tsapanou, Gu et al. 2015). Moreover, specific sleep problems have been found to be significant risk factors for developing both Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) and dementia, mostly Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) type (Jelicic, Bosma et al. 2002, Yaffe, Laffan et al. 2011, Ju, McLeland et al. 2013, Tsapanou, Gu et al. 2015). Objective cognitive performance is often, but not always, related to subjective cognitive decline (SCD), which is the self-perception of cognitive changes in comparison to a previously normal state (Tandetnik, Farrell et al. 2015).

SCD may be an early indicator for impending cognitive impairment in older adults, including conversion to MCI and then dementia (Jessen, Wiese et al. 2010, Jacinto, Brucki et al. 2014). However, other studies found no link between SCD and cognition (Jungwirth, Fischer et al. 2004). The inconsistency of findings across studies likely reflects variability in the measurement of both SCD and objective cognition, as well as the multidimensional nature of SCD; indeed, SCD has been linked to negative affect (Dux, Woodard et al. 2008), personality (Hanninen, Reinikainen et al. 1994), self-perceived physical functioning (Lautenschlager, Cox et al. 2008), and a variety of indicators of well-being (Verhaeghen, Geraerts et al. 2000). Very little is known about the link between SCD and sleep in older adults, a modifiable factor that could play an important role in contributing to SCD, and in general cognition.

Of the studies that have examined sleep in relation to SCD, one study using both sleep questionnaire and polysomnography, as well as an extensive evaluation for SCD and the Immediate-Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing battery showed that sleep loss was associated with increased severity of SCD (Stocker, Khan et al. 2017). Poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness were also linked to SCD in older adults, in two different studies, one using an objective neuropsychological battery (CERAD-KN), a subjective memory complaints questionnaire, and a subjective sleep questionnaire (Pittsburg sleep index) (Kang, Yoon et al. 2015), and the other using both objective and subjective sleep measurement, a cognitive neuropsychological assessment and an SCD scale ( Tardy, Gonthier et al. 2015). Furthermore, in a systematic review of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), increased subjective sleepiness was associated with more SCD (Vaessen, Overeem et al. 2015). However, another study using both actigraphy and sleep questionnaires, examining only complaints about memory (with the Memory assessment Complaint Questionnaire), and without using objective cognitive measures showed that subjective sleep quality did not predict memory SCD, in contrast with objective sleep quality (Cavuoto, Ong et al. 2016).

There are, thus, gaps in the existing literature on the association between sleep and SCD. Most of the studies have used relatively small sample sizes, have included younger age groups, or have considered older participants of a very narrow age group (i.e. 63–68), limiting the generalizability of the results. Notably, the majority of previous reports did not incorporate an extensive questionnaire covering a large range of SCD. Existing research on this topic typically has also not incorporated a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation, which would allow for detailed differential diagnosis and an accurate description of the cognitive status of each participant, eliminating patients with MCI or AD from the analyses. There is no existing work on sleep and SCD that has included a replication group, and, most of the existing studies do not consider the objective cognitive performance of the participants.

In the current study we tried to bridge the gaps of the existing literature. We aimed to examine the hypothesis that sleep problems are associated with SCD in the elderly. Such investigation would provide important information about the cognitive status of participants and would raise the awareness of clinicians for people without objective cognitive decline who report subjective cognitive deficits. We examined the association between self-reported sleep problems and SCD in cognitively healthy older adults, not only in one study as previous designs, but with a replication large cohort, with similar design, but yet, different population. The two studies were the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP), and the HEllenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD).

Methods

Cohorts-Participants

WHICAP is a community-based research study aimed at identifying risk factors and biomarkers for aging and AD in a multi-ethnic cohort that includes Non-Hispanic White, African-American, and Hispanic participants (Tang, Stern et al. 1998, Tang, Cross et al. 2001, Manly, Bell-McGinty et al. 2005). The age of enrollment of the participating pool was 65 years or older. Volunteers were recruited irrespectively of their cognitive status. The evaluation was conducted in English or Spanish. Informed consent, as approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute was obtained prior to study participation.

HELIAD is a population-based, multidisciplinary study designed to estimate the prevalence and incidence of MCI, AD, other types of dementia, as well as other neuropsychiatric conditions of aging in the Greek population (65 years or older). HELIAD’s design is similar to WHICAP. The study measures demographic, medical, social, environmental, clinical, nutritional, and neuropsychological determinants as well as the lifestyle activities of each participant. The evaluation was conducted in Greek. HELIAD has been approved by the IRB of Aeginition Hospital, at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, as well as by the IRB of the University of Thessaly. More detailed information about the specific study can be found in previously published work (Dardiotis, Kosmidis et al. 2014, Anastasiou, Yannakoulia et al. 2017, Ntanasi, Yannakoulia et al. 2017).

Clinical and cognitive evaluations

A structured, in-person interview, consisting of a medical history report, was conducted for each participant, in both studies. All participants provided information about their current health status, any neurological conditions, past medical problems, surgical procedures, hospitalizations, and any current use of medication. Information regarding their daily activities, physical exercise, and diet was also collected. Examination was conducted by well-trained physicians and/or neuropsychologists.

All participants were examined with a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, which, based on a previously reported factor analysis in WHICAP (Siedlecki, Manly et al. 2010), was summarized in the following cognitive domains: memory, executive functioning, language, and speed of processing-attention. For the purposes of the current study, we created a general objective cognition variable, which was the mean composite score of the scores from each cognitive domain. The HELIAD battery and composite summary score was similar to the WHICAP battery (Kosmidis HM. 2017, Tsapanou, Gu et al. 2017). For both studies, z-scores for each cognitive domain were derived based on the means and standard deviations (SD) of participants without dementia. The z-scores were averaged to derive the composite cognitive score. Higher z-score indicates better cognitive performance.

All participants in both studies underwent a thorough diagnostic examination to determine cognitive and functional status. Changes in performance of daily activities due to a perceived decline in memory or non-memory were recorded using relevant questions in the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale for the HELIAD and from the Blessed Dementia Scale for the WHICAP study. We matched the questions used to both studies as accurately as possible. The diagnosis of MCI or dementia was based on standard research criteria, using all available information at a consensus conference consisting of at least one neurologist and one neuropsychologist. The diagnosis of dementia required evidence of cognitive deficit, impairment in social or occupational function, and cognitive and socio-occupational functional decline, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Revised Third Edition. The National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association were used for the diagnosis of probable or possible AD.

As the awareness of people with MCI varies, while demented individuals tend to underestimate their cognitive or general health status due to poor insight, their answers in both sleep and cognitive complaints questions most likely will not reflect their actual situation (Farias, Mungas et al. 2005). Moreover, demented patients are more likely to refer both more sleep and SCD, most likely due to the neurodegenerative disease. For these reasons, participants with MCI or dementia were excluded from our analysis. We made a further exclusion of participants having severe depression or anxiety, as there is evidence that these disorders significantly affect sleep regulation, SCD, and cognitive performance. Depression and anxiety in WHICAP were measured using the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD), a screening test for depression and depressive disorder defined by the American Psychiatric Association DSM-V. Possible answers were no/yes, with a rating of 0–1 respectively. Participants with a score ≥4, indicating severe depression/anxiety disorder, were excluded. Depression in HELIAD was determined on the basis of the consensus diagnosis, the use of antidepressants or the score of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), which is a 15-item self-reported questionnaire. In the analysis, GDS was used as a dichotomous variable, with a cut-off score of 6 (Yesavage 1988,). Assessment of anxiety in HELIAD was based on the Hospital anxiety and depression scale. This is a 7-item self-reported questionnaire. The specific scale was used dichotomously, with a cut-off score of 8 (Zigmond and Snaith 1983, Bjelland, Dahl et al. 2002, Michopoulos, Douzenis et al. 2008).

Sleep measures

In both studies, sleep problems were assessed with the Sleep Scale from the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS-SS) (Hays, Martin et al. 2005). Based on the existing literature, self-reported sleep efficiency has been found to be as accurate as the objective sleep measure of polysomnography and actigraphy (Kushida, Chang et al. 2001). The MOS-SS is a self-reported 12-item questionnaire (Spritzer 2003, Hays, Martin et al. 2005). Sleep problems were examined using the Sleep Index II (Hays 1995) including the following questions: During the past 4 weeks: 1. “How long did it usually take for you to fall asleep?” How often did you: 2. “Feel that your sleep was not quiet (moving restlessly, feeling tense, speaking, etc., while sleeping)?” 3. “Get enough sleep to feel rested upon waking in the morning?” 4. “Awaken short of breath or with a headache?” 5. “Feel drowsy or sleepy during the day?” 6. “Have trouble falling asleep?” 7. “Awaken during your sleep time and have trouble falling asleep again?” 8. “Have trouble staying awake during the day?” 9. “Get the amount of sleep you needed?”. Each of the questions has a possible rating of 1–6, based on the frequency of the sleep problem. The sum of the sleep problems variable had a range of 1–54. Based on the manual, we reverse-scored pre-specified sleep items so that higher scores indicate more sleep problems. For the purposes of the specific analyses, and based on the MOS-SS manual, the Sleep Index II variable (from now on referred as “sleep problems” variable) was derived by averaging the sum of the scores from the above questions, and had a range of 1–6. Information regarding the reliability and validity of the MOS-SS in the Greek population can be found in a previous publication (Tsapanou, Gu et al. 2017).

Subjective Cognitive Decline

In both studies, participants were interviewed about forgetfulness and specific cognitive problems by means of a structured cognitive/functional complaint questionnaire, starting with a query about whether or not they have memory problems in general. Items on this scale were answers from combined functional questions to ensure coverage of SCD across various cognitive domains. The domains of the subjective complaints were the following: memory, naming, orientation, and calculation. The possible rating for each one of the SCD items was 0–1. Subjective memory decline score was based on one question (dichotomous variable, 0–1). Subjective naming decline score was based on 2 questions. A positive answer to at least one of them, resulted in a subjective naming decline score of 1 (dichotomous variable, 0–1). Subjective orientation decline score was based on 5 questions. A positive answer to at least one of them, resulted in a subjective orientation decline score of 1 (dichotomous variable, 0–1). Subjective calculation decline score was based on 3 questions. A positive answer to at least one of them, resulted in a subjective orientation decline score of 1 (dichotomous variable, 0–1) (see Appendix).

The total SCD was the sum of the subjective cognitive sub-categories, and had a possible rating of 0–4, with higher scores indicating more SCD. To ensure greater homogeneity of the categories given the sample size as scores of 3 or 4 were relatively rare, we created a trichotomous total SCD variable: 0 for no complaint, 1 for expressing one complaint, and 2 for expressing two or more complaints.

In the main analysis we used the sum of the SCD. Then, we ran further exploratory analyses for the association between sleep and the specific subjective cognitive sub-categories. All questions were asked similarly in both studies.

Covariates

Age and numbers of years of education were used as continuous variables. As sleep medication and other medications can affect both sleep and cognitive performance, especially among the elderly, we created a continuous variable for the total number of medications taken as a covariate. The specific variable consisted of the following: narcotics, hypnotics, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, anticholinergics, and phenobarbital. Sex was used as a dichotomous variable. We also created a covariate of comorbidities that may act as risk factors for cognitive decline, including the following Boolean variables: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (including myocardial infarction), congestive heart failure, and stroke. We then added depression and anxiety as continuous variables. We further used as a continuous covariate the global objective cognitive performance, which was the mean composite score based on the performance in the cognitive domains, as previously described. Covariates were used the same way in both studies.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 23 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois). Nominally significant alpha values were defined as p < 0.05. We ran the analyses in the two cohorts separately.

We used multinomial regression models with sleep problems as the predictor and SCD (0, 1, 2) as the outcome, with no complaints (0) as the reference category. The models were first unadjusted and then adjusted for age, sex, education, sleep medication/medication affecting cognition, and comorbidities. We further controlled for general objective cognition, using the variable described at the neuropsychological evaluation section.

In further exploratory analyses, we examined the associations between sleep problems and specific subjective complaints regarding memory, naming, orientation, and calculation difficulties. We used logistic regression models, with sleep problems variable as the predictor, and each of the SCD domains as the outcome (0–1). The models were adjusted for age, sex, education, sleep medication and medication affecting cognition, as well as comorbidities.

Results

Our initial sample in WHICAP consisted of 2993 participants having sleep or cognitive data. We excluded those with MCI (N=516), dementia (N=243), severe depression or anxiety (N=306), and after excluding participants with missing data (N=352), the final sample consisted of 1576 participants. Our initial sample in HELIAD consisted of 1847 participants. After excluding participants with MCI (N=219), those with dementia (N=89), those with severe depression or anxiety (N=28) and those with missing data (N=55), the final sample consisted of 1456 participants. Compared to those with missing data, our samples did not differ significantly in the demographic characteristics.

Most of the WHICAP participants did not have any complaint of SCD, while most of the HELIAD participants reported at least one complaint of SCD. In both studies, the majority of participants were women, and the mean age of the total sample was 73–74 years old. The mean education level was 12 years for WHICAP, while 8 years for HELIAD (Tables 1 and 2). The number of participants [N (%)] having complaints for each of the subjective sub-cognitive category was as follows: WHICAP: Memory: 292 (18.6), Naming: 401 (25.5), Orientation: 7 (0.4), Calculations: 18 (1.2). HELIAD: Memory: 408 (28.1), Naming: 378 (26), Orientation: 78 (5.4), Calculations: 38 (2.6).

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the WHICAP participants, by groups (SCD=0, SCD=1, SCD≥2).

| Characteristics | SCD (0) (N=891) |

SCD (1) (N=344) |

SCD (≥2) (N=341) |

F, p | All (N=1576) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 74 (6) | 74 (6) | 74 (5) | 0.446, 0.640 | 74 (5.7) |

| Sex, women, Ν (%) | 570 (65.5) | 222 (61.2) | 245 (71.4) | 4.183, 0.015 | 1037 (65.8) |

| Education (years), Mean (SD) | 11 (5) | 13 (5) | 13 (5) | 15.066, ≤0.0001 | 12 (4.8) |

| Comorbidities, Mean (SD) | 1.12 (0.94) | 1.08 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.93) | 0.515, 0.598 | 1.12 (0.9) |

| Sleep/cogn meds, yes, N (%) | 92 (10.6) | 44 (12.1) | 61 (17.7) | 5.942, 0.003 | 197 (12.5) |

| Obj. cognition, z-score, Mean (SD) | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.4) | 23.851, ≤0.0001 | 0.585 (0.5) |

| Sleep problems, Mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.9 (0.7) | 18.018, ≤0.0001 | 1.8 (0.6) |

Table 2:

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the HELIAD participants, by SCD groups (SCD=0, SCD=1, SCD≥2).

| Characteristics | SCD (0) (N=388) |

SCD (1) (N=617) |

SCD (≥2) (N=451) |

F, p | All (N=1456) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 72 (5) | 73 (5) | 73 (5) | 4.848, 0.008 | 73 (5.2) |

| Sex, women, Ν (%) | 220 (56.7) | 359 (58.2) | 297 (65.9) | 3.244, 0.039 | 880 (60.5) |

| Education (years), Mean (SD) | 9.3 (5.5) | 7.2 (4.3) | 8.3 (4.6) | 22.449, ≤0.0001 | 7.8 (4.7) |

| Comorbidities, Mean (SD) | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.9) | 8.820, ≤0.0001 | 1.05 (0.88) |

| Sleep/cogn meds, yes, N (%) | 54 (13.9) | 108 (17.5) | 95 (21.1) | 6.569, 0.001 | 257 (17.7) |

| Obj. cognition, z-score, Mean (SD) | 0.14 (0.6) | −0.16 (0.72) | −0.02 (0.66) | 19.172, ≤0.0001 | −0.078 (0.7) |

| Sleep problems, Mean (SD) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.9) | 12.467, ≤0.0001 | 1.96 (0.8) |

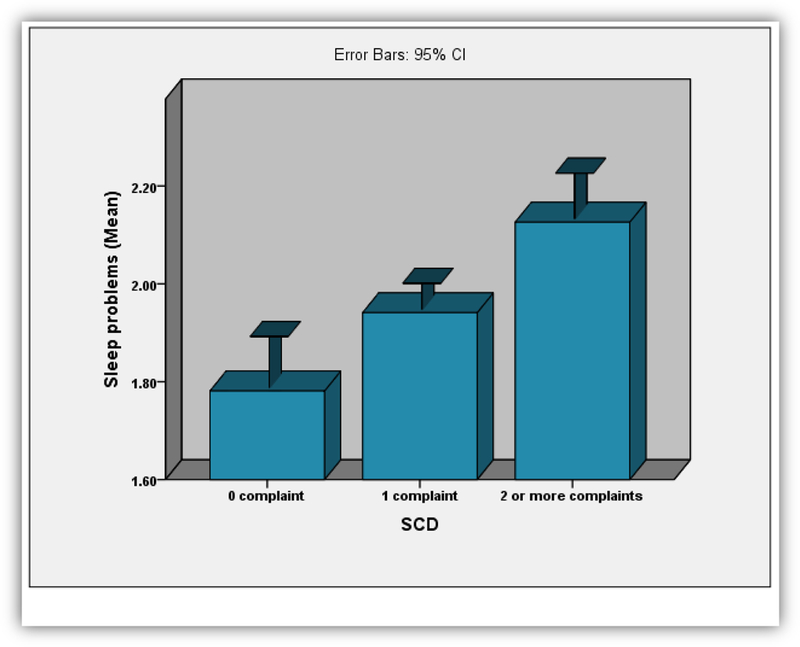

In the unadjusted multinomial regression model, more sleep problems were associated with more total SCD in WHICAP, for both one complaint: β=1.515 (95% CI: 1.248–1.839), p≤0.0001, and two or more complaints: β=1.965 (95% CI: 1.625–2.370), p≤0.0001 (Figure 1). Associations between sleep problems and SCD were similar for the HELIAD study: one complaint: β=1.287 (95% CI: 1.064–1.557), p=0.009, and two or more complaints: β=1.632 (95% CI: 1.328–2.005), p≤0.0001 (Figure 2). In the adjusted models, associations remained significant between more sleep problems and more total SCD in both studies (Table 3). Results remained significant even after adding as covariates depression and anxiety, so that more complaints about general cognition were associated with more sleep problems in both studies; WHICAP: SCD and sleep problems: 1 complaint: β=1.44 (1.179–1.772), p≤0.0001, ≥2 complaints: β= 1.66 (1.357–2.032), p≤0.0001. HELIAD: SCD and sleep problems: 1 complaint: β=1.51 (1.143–2.004), p=0.004, ≥2 complaints: β=2.06 (1.550–2.726), p≤0.0001. The associations between sleep problems and SCD remained significant after adding global objective cognition as an additional covariate (Table 3).

Figure 1:

Bar graph depicting the association between SCD and Sleep Problems among cognitively healthy older adults from the WHICAP study. More SCD (0=0 complaints, 1=1 complaint, 2=2 or more complaints) was associated with more sleep problems

Figure 2:

Bar graph depicting the association between SCD and Sleep Problems among cognitively healthy older adults from the HELIAD study. More SCD (0=0 complaints, 1=1 complaint, 2=2 or more complaints) was associated with more sleep problems

Table 3:

Regression models for the association between Sleep Problems and SCD in the two cohorts. Models adjusted for age, sex, education, comorbidities, sleep medication and medication affecting cognition. Further adjustment for general objective cognitive performance. SCD reference category=0. 1=1 complaint, 2=2 or more complaints.

| SCD | Sleep Problems | |

|---|---|---|

| WHICAP β (95% CI), (p) |

HELIAD β (95% CI), (p) |

|

| SCD (total) |

1: 1.55 (1.274–1.890), ≤0.0001 ≥2: 1.93 (1.592–2.344), ≤0.0001 |

1: 1.16 (0.953–1.411), 0.138 ≥2: 1.48 (1.201–1.829), ≤0.0001 |

| SCD adjusted also for general objective cognition |

1: 1.54 (1.258–1.874), ≤0.0001 ≥2: 1.91 (1.577–2.323), ≤0.0001 |

1: 1.17 (0.962–1.434), 0.115 ≥2: 1.48 (1.196–1.836), ≤0.0001 |

| Subjective Complaints by Cognitive Domain | ||

| Memory | 1.38 (1.146–1.661), 0.001 | 1.27 (1.109–1.458), 0.001 |

| Naming | 1.66 (1.402–1.970), ≤0.0001 | 1.23 (1.070–1.408), 0.004 |

| Orientation | 1.07 (0.347–3.324), 0.901 | 1.79 (1.419–2.270), ≤0.0001 |

| Calculations | 1.85 (1.059–3.243), 0.031 | 1.78 (1.282–2.472), 0.001 |

Further exploratory analysis revealed that increased sleep problems were associated with subjective complaints about memory, naming, and calculations for both studies, and orientation for HELIAD (Table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the association between self-reported sleep problems and subjective cognitive decline in two large cohorts of cognitively healthy older adults. Increased sleep problems were associated with increased SCD, independent of demographic, clinical factors, and an index of global objective cognition. Sleep problems were associated with complaints regarding memory, naming, and calculations in both cohorts and with orientation complaints in HELIAD only. More sleep problems were associated with more complaints for all the cognitive sub-categories.

Our results are in accordance with a relatively scarce literature showing an association between sleep problems and SCD (Kang, Yoon et al. 2015, Vaessen, Overeem et al. 2015, Stocker, Khan et al. 2017). Socioeconomic factors could play a significant role to the above association. Poor sleep quality is more frequent among women, those with lower occupational status, and advanced age (Beck, Leon et al. 2009, Hoefelmann, Lopes Ada et al. 2013). Demographics and more specifically, the higher proportion of women could partly explain such associations, as many demographic factors and more precisely the hormonal profile of women have been linked to both SCD and sleep problems. Menstrual cycles, and menopause can alter sleep architecture and self-perception as well, and have a direct influence on general health. However, after adjusting for age, sex, education, comorbidities, depression and anxiety, the association between sleep problems and SCD remained statistically significant in both cohorts, a fact showing that other probable socioeconomic factors that we did not have the opportunity to account for in the current study (i.e. income, substance abuse) could also play a significant role to the association between sleep and SCD.

We could hypothesize that sleep problems may be causing more SCD. Poor sleep quality has been associated with low cognitive performance, especially in the elderly (Yaffe, Laffan et al. 2011, Tsapanou, Gu et al. 2015). Although we considered only individuals without objective cognitive deficits, participants with more sleep problems could feel less cognitively effective during the day, therefore, expressing more SCD. Considering SCD as a possible consequence of poor sleep quality, future clinical interventions directed at sleep could help addressing the subjective cognitive complaints. Further longitudinal research on this topic could provide us with more accurate information on the directionality of the above association.

Reverse causality cannot be excluded. An alternative explanation of our findings is that both SCD and sleep dysregulation are initial symptoms of an undetected subclinical neurodegenerative disease. Indeed, MCI and dementia -especially AD- have been both associated with increased sleep dysregulation (Lim, Kowgier et al. 2013, Tsapanou, Gu et al. 2015), and existing literature points to the presence of AD biomarkers in adults expressing SCD. Overall, therefore, although we were careful to exclude subjects with dementia or even MCI, and to additionally adjust for objective cognition, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that both sleep problems and the self-perception of the cognitive performance could still be an indication of preclinical cognitive alterations which could lead to future dementia. Longitudinal research could help identify whether SCD is a very early symptom followed by objective cognitive decline and dementia.

The association between sleep and SCD could partially be explained by mood, personality, or attitudinal factors. Many studies have shown that SCD is associated with depressive symptoms and personality traits. For example, high neuroticism has been significantly associated with SCD. Depression and high neuroticism have also been linked to sleep dysregulations. Although we excluded participants with significant depression and anxiety, it is still possible that certain psychological characteristics not captured by our psychiatric scales could influence the association between sleep and SCD. Broad attitudes or perceptions about health may contribute to the link between SCD and subjective reports of sleep problems. Recent evidence suggests that people with subjective cognitive difficulties are more likely to report difficulties in physical functioning, independent of objective functioning in these areas, perhaps reflecting broad attitudes or perceptions about health; such attitudes may pertain to sleep as well.

There are some limitations in the present study. First, we did not have the opportunity to use objective measures of sleep such as polysomnography or actigraphy. Moreover, the answers to the sleep questionnaire referred to the last four weeks before the evaluation, and may not accurately represent long-term sleep patterns. The questions for SCD did not derive from a previously widely accepted, validated questionnaire. The cross-sectional design of the study is another limitation, in so far as elucidating the directionality of the associations; further longitudinal analyses should be conducted.

There are several strengths of the current study. To our knowledge, this is the first examination of sleep problems and SCD that includes a replication study, increasing the confidence of the findings and the generalizability of the noted associations. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the largest sample size study examining the association between sleep and subjective cognitive complaints in the elderly. The Mediterranean is a region with considerably different sleep habits and patterns than other regions (i.e. frequent napping during the day); additional information and enhanced variability on sleep is considered with the inclusion of the HELIAD Mediterranean population. Another strength of the study is that we were able to examine not only subjective cognitive complaints in total, but also the specific categories of the complaints. Clinical evaluation was conducted in a systematic way by dementia experts, permitting a fine-tuned classification of the cognitive status of our participants and exclusion from the analyses of all subjects with MCI and dementia. We also conducted comprehensive neuropsychological assessment of all participants, which gave us the opportunity to control for global objective cognitive performance.

Based on the present findings, clinicians should be aware of potentially co-existing sleep problems when cognitive complaints are reported. Early complaints about cognitive deficits, with sleep problems, before the presence of objective cognitive impairment, could be an ominous sign for participants in high risk of developing a cognitive decline. Subjective complaints should not be underestimated; on the contrary, they should sound a note of warning and urge these adults for a more precise follow-up. These results encourage further longitudinal research with objective sleep assessments to clarify the directionality underlying the association between sleep and SCD. By improving understanding of the way in which these important factors interact, such research will serve to enhance the quality of life of older adults.

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by the following grants:

WHICAP: P01AG007232, R01AG037212, RF1AG054023, R00AG042483 funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, United States, through Grant Number UL1TR001873.

HELIAD: IIRG-09-133014 from the Alzheimer’s Association; 189 10276/8/9/2011 from the ESPA-EU program Excellence Grant (ARISTEIA), which is co-funded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, ΔΥ2β/οικ.51657/14.4.2009 from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece), “IKY/Siemens Research excellence programs fellowship”.

Appendix

Summarized questions used to create the SCD in both studies. The score for dichotomous variables (MC, NC, OC, CC) is 0 if all answers are negative for SCD and 1 in case of at least one positive answer; the score for the quantitative metric (SCD) is the sum of all positive responses regarding memory, naming, orientation and/or calculation complaints (scores of 4 or 3 were relatively rare and merged with 2 into a score of 2).

| SCD definition | Questions/topics | |

|---|---|---|

| MC | Memory Complaint (0–1) | Do you have any problems with your memory? |

| NC | Naming Complaints (0–1) | • Do you have difficulty remembering the names of people in your family or close friends? (do not include transient mistakes) • Do you often have to stop in the middle of saying something because you have difficulty or problems remembering the right word? |

| OC | Orientation Complaints (0–1) | • Inability to find way about indoors • Inability to find way about familiar streets • Inability to interpret surroundings; for example, to recognize whether in hospital or at home; to discriminate between patients, doctors, nurse, relatives, other hospital staff, etc. • Do problems with your memory make it difficult for you to go outside by yourself? • Can you travel independently on public transportation or drive your car? |

| CC | Calculation Complaints (0–1) | • Inability to cope with small sums of money • Do problems with your memory make it difficult for you to keep track of your personal business like paying bills and handling money? • Can you manage your financial matters independently (budgets, write checks, pay rent, bills, go to bank), collect and keep track of your income? |

| SCD | Sum of Complaints in All domains | MC + NC + OC + CC |

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no financial or personal conflicts.

References

- Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M, Kosmidis MH, Dardiotis E, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Sakka P, Arampatzi X, Bougea A, Labropoulos I and Scarmeas N (2017). “Mediterranean diet and cognitive health: Initial results from the Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Ageing and Diet.” PLoS One 12(8): e0182048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck F, Leon C, Pin-Le Corre S and Leger D (2009). “[Sleep disorders: Sociodemographics and psychiatric comorbidities in a sample of 14,734 adults in France (Barometre sante INPES)].” Rev Neurol (Paris) 165(11): 933–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT and Neckelmann D (2002). “The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review.” J Psychosom Res 52(2): 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavuoto MG, Ong B, Pike KE, Nicholas CL, Bei B and Kinsella GJ (2016). “Better Objective Sleep Quality in Older Adults with High Subjective Memory Decline.” J Alzheimers Dis 53(3): 943–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardiotis E, Kosmidis MH, Yannakoulia M, Hadjigeorgiou GM and Scarmeas N (2014). “The Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD): rationale, study design, and cohort description.” Neuroepidemiology 43(1): 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dux MC, Woodard JL, Calamari JE, Messina M, Arora S, Chik H and Pontarelli N (2008). “The moderating role of negative affect on objective verbal memory performance and subjective memory complaints in healthy older adults.” J Int Neuropsychol Soc 14(2): 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farias ST, Mungas D and Jagust W (2005). “Degree of discrepancy between self and other-reported everyday functioning by cognitive status: dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy elders.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20(9): 827–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis KN1, T. M., Iacovides A, Yesavage J, O’Hara R, Kazis A, Ierodiakonou C. (1999). “The validation of the short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece.” Aging (Milano). 11(6): 367–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanninen T, Reinikainen KJ, Helkala EL, Koivisto K, Mykkanen L, Laakso M, Pyorala K and Riekkinen PJ (1994). “Subjective memory complaints and personality traits in normal elderly subjects.” J Am Geriatr Soc 42(1): 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Martin SA, Sesti AM and Spritzer KL (2005). “Psychometric properties of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep measure.” Sleep Med 6(1): 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM (1995). “User’s Manual for the Medical Outcomed Study (MOS) Core Measures of Health-Related Quality of Life.” (Published by RAND; ). [Google Scholar]

- Hoefelmann LP, Lopes Ada S, da Silva KS, Moritz P and Nahas MV (2013). “Sociodemographic factors associated with sleep quality and sleep duration in adolescents from Santa Catarina, Brazil: what changed between 2001 and 2011?” Sleep Med 14(10): 1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto AF, Brucki SM, Porto CS, Arruda Martins M and Nitrini R (2014). “Subjective memory complaints in the elderly: a sign of cognitive impairment?” Clinics (Sao Paulo) 69(3): 194–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaussent I, Bouyer J, Ancelin ML, Berr C, Foubert-Samier A, Ritchie K, Ohayon MM, Besset A and Dauvilliers Y (2012). “Excessive sleepiness is predictive of cognitive decline in the elderly.” Sleep 35(9): 1201–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelicic M, Bosma H, Ponds RW, Van Boxtel MP, Houx PJ and Jolles J (2002). “Subjective sleep problems in later life as predictors of cognitive decline. Report from the Maastricht Ageing Study (MAAS).” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17(1): 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, Eifflaender-Gorfer S, Haller F, Kolsch H, Luck T, Mosch E, van den Bussche H, Wagner M, Wollny A, Zimmermann T, Pentzek M, Riedel-Heller SG, Romberg HP, Weyerer S, Kaduszkiewicz H, Maier W, Bickel H, German C Study on Aging and G. Dementia in Primary Care Patients Study (2010). “Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 67(4): 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju YE, McLeland JS, Toedebusch CD, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Duntley SP, Morris JC and Holtzman DM (2013). “Sleep quality and preclinical Alzheimer disease.” JAMA Neurol 70(5): 587–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungwirth S, Fischer P, Weissgram S, Kirchmeyr W, Bauer P and Tragl KH (2004). “Subjective memory complaints and objective memory impairment in the Vienna-Transdanube aging community.” J Am Geriatr Soc 52(2): 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Yoon IY, Lee SD, Kim T, Lee CS, Han JW, Kim KW and Kim CH (2015). “Subjective memory complaints in an elderly population with poor sleep quality.” Aging Ment Health: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmidis HM., V. G. S., Anastasiou CA, Yannakoulia M, Dardiotis E, Hadjigeorgiou G, Sakka P, Scarmeas N (2017). “Dementia prevalence in Greece: the Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD).” (under review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushida CA, Chang A, Gadkary C, Guilleminault C, Carrillo O and Dement WC (2001). “Comparison of actigraphic, polysomnographic, and subjective assessment of sleep parameters in sleep-disordered patients.” Sleep Med 2(5): 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, Foster JK, van Bockxmeer FM, Xiao J, Greenop KR and Almeida OP (2008). “Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial.” JAMA 300(9): 1027–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim AS, Kowgier M, Yu L, Buchman AS and Bennett DA (2013). “Sleep Fragmentation and the Risk of Incident Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline in Older Persons.” Sleep 36(7): 1027–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Bell-McGinty S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y and Mayeux R (2005). “Implementing diagnostic criteria and estimating frequency of mild cognitive impairment in an urban community.” Arch Neurol 62(11): 1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michopoulos I, Douzenis A, Kalkavoura C, Christodoulou C, Michalopoulou P, Kalemi G, Fineti K, Patapis P, Protopapas K and Lykouras L (2008). “Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): validation in a Greek general hospital sample.” Ann Gen Psychiatry 7: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntanasi E, Yannakoulia M, Kosmidis MH, Anastasiou CA, Dardiotis E, Hadjigeorgiou G, Sakka P and Scarmeas N (2017). “Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Frailty.” J Am Med Dir Assoc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedlecki KL, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Schupf N, Tang MX and Stern Y (2010). “Do neuropsychological tests have the same meaning in Spanish speakers as they do in English speakers?” Neuropsychology 24(3): 402–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spritzer KH,R (2003). “MOS Sleep Scale: a manual for use and scoring, Version 1.0. Los Angeles, CA; .” [Google Scholar]

- Stocker RP, Khan H, Henry L and Germain A (2017). “Effects of Sleep Loss on Subjective Complaints and Objective Neurocognitive Performance as Measured by the Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing.” Arch Clin Neuropsychol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandetnik C, Farrell MT, Cary MS, Cines S, Emrani S, Karlawish J and Cosentino S (2015). “Ascertaining Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Comparison of Approaches and Evidence for Using an Age-Anchored Reference Group.” J Alzheimers Dis 48 Suppl 1: S43–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, Merchant C, Lantigua R, Costa R, Stern Y and Mayeux R (2001). “Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan.” Neurology 56(1): 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, Andrews H, Feng L, Tycko B and Mayeux R (1998). “The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics.” JAMA 279(10): 751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardy M, Gonthier R, Barthelemy JC, Roche F and Crawford-Achour E (2015). “Subjective sleep and cognitive complaints in 65 year old subjects: a significant association. The PROOF cohort.” J Nutr Health Aging 19(4): 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsapanou A, Gu Y, Manly J, Schupf N, Tang MX, Zimmerman M, Scarmeas N and Stern Y (2015). “Daytime Sleepiness and Sleep Inadequacy as Risk Factors for Dementia.” Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 5(2): 286–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsapanou A, Gu Y, O’Shea D, Eich T, Tang MX, Schupf N, Manly J, Zimmerman M, Scarmeas N and Stern Y (2015). “Daytime somnolence as an early sign of cognitive decline in a community-based study of older people.” Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsapanou A, Gu Y, O’Shea DM, Yannakoulia M, Kosmidis M, Dardiotis E, Hadjigeorgiou G, Sakka P, Stern Y and Scarmeas N (2017). “Sleep quality and duration in relation to memory in the elderly: initial results from the Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Ageing and Diet.” Neurobiol Learn Mem. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsapanou A, Gu Y, O’Shea DM, Yannakoulia M, Kosmidis M, Dardiotis E, Hadjigeorgiou G, Sakka P, Stern Y and Scarmeas N (2017). “Sleep quality and duration in relation to memory in the elderly: Initial results from the Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet.” Neurobiol Learn Mem 141: 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaessen TJ, Overeem S and Sitskoorn MM (2015). “Cognitive complaints in obstructive sleep apnea.” Sleep Med Rev 19: 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Geraerts N and Marcoen A (2000). “Memory complaints, coping, and well-being in old age: a systemic approach.” Gerontologist 40(5): 540–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Jiang CQ, Lam TH, Zhang WS, Cherny SS, Thomas GN and Cheng KK (2014). “Sleep duration and memory in the elderly Chinese: longitudinal analysis of the Guangzhou Biobank Cohort Study.” Sleep 37(11): 1737–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Laffan AM, Harrison SL, Redline S, Spira AP, Ensrud KE, Ancoli-Israel S and Stone KL (2011). “Sleep-disordered breathing, hypoxia, and risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older women.” JAMA 306(6): 613–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA (1988). “Geriatric Depression Scale.” Psychopharmacol Bull 24(4): 709–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS and Snaith RP (1983). “The hospital anxiety and depression scale.” Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6): 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]