Abstract

Objective

Rebleeding remains a frequent and catastrophic event leading to poor outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Reduced platelet function after the initial bleed is associated with higher risk of early rebleeding. Desmopressin (DDAVP) is a well known hemostatic agent and recent guidelines already suggest its use in subjects exposed to antiplatelet drugs. The authors hypothesized that DDAVP administration to SAH patients at admission would be associated with lower risks of rebleeding.

Methods

The authors performed an observational cohort study of patients enrolled in the Columbia University SAH Outcome Project between August 1996 and August 2015. The authors compared the rate of rebleeding between patients who were and those who were not treated with DDAVP. After adjustment for known predictors, logistic regression was used to measure the association between treatment with DDAVP and risks of rebleeding.

Results

Among 1639 SAH patients, 12% were treated with DDAVP. The main indication for treatment was suspected exposure to an antiplatelet agent. The overall incidence of rebleeding was 9% (1% among patients treated with DDAVP compared to 8% among those not treated). After adjustment for antiplatelet use and known predictors, treatment with DDAVP was associated with a 45% reduction in the risks of rebleeding (adjusted OR 0.55 95% C.I. [0.27, 0.97]). DDAVP was associated with a higher incidence of hyponatremia, but not with thrombotic events or delayed cerebral ischemia.

Conclusions

Treatment with DDAVP was associated with a lower risk of rebleeding among patients with SAH. These findings support further study of DDAVP as first-line therapy for medical hemostasis in patients with SAH.

INTRODUCTION

Rebleeding is the most important complication contributing to early morbidity and mortality among patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). It is associated with a dismal prognosis, significantly reducing the chances of survival and functional independence[1] Despite a shift in paradigm towards swift coiling or clipping, rebleeding rates of 6% to 10% are still reported[2]. These catastrophic events occur within the first 24 hours but oftentimes within the first 3 hours after the initial bleed, emphasizing the crucial need for simple interventions that could be provided in a timely fashion[3].

Platelets are a crucial component of primary hemostasis and therefore constitute a potential target for prevention. In fact, SAH itself induces abnormal platelet aggregability[4] which, in turn, is strongly correlated to ultra-early rebleeding, even more so than classical risk factors such as initial neurological status[5]. Compounding this endogenous phenomenon, concurrent antiplatelet use could potentially further increase the risk of rebleeding, as one retrospective study found that exposure to aspiring multiplied by three the risks of rebleeding[6]. This data have compelled many centers to adopt targeted therapy among users of antiplatelet and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID), using platelet transfusions, desmopressin (DDAVP), or both to enhance hemostasis. However, according to a recently published randomized open-label trial[7], platelet transfusions seem to increase the risk of death or dependence when used to treat spontaneous cerebral hemorrhage patients taking antiplatelet therapy, leaving clinicians with few alternatives but DDAVP.

DDAVP is a synthetic analog of the hormone vasopressin which increases baseline plasma levels of von Willebrand factor and factor VIII three- to five-fold and is used to mitigate bleeding in multiple congenital or acquired platelet disorders[8]. DDAVP has been shown to reverse medication-induced platelet dysfunction in vitro and in intracranial hemorrhage patients[9], but the clinical utility of its use in SAH patients has not been explored. Despite the relative lack of evidence, the most recent guidelines from the Neurocritical Care Society suggests consideration of a single dose of DDAVP for acute intracranial hemorrhage of any type if the patient was exposed to antiplatelet agents[10]. This approach was adopted at Columbia University Medical Center starting in 2008, providing us with a unique opportunity to study the relationship between DDAVP treatment at admission and the risk of rebleeding in a prospective cohort of patients with SAH.

METHODS

Study Population

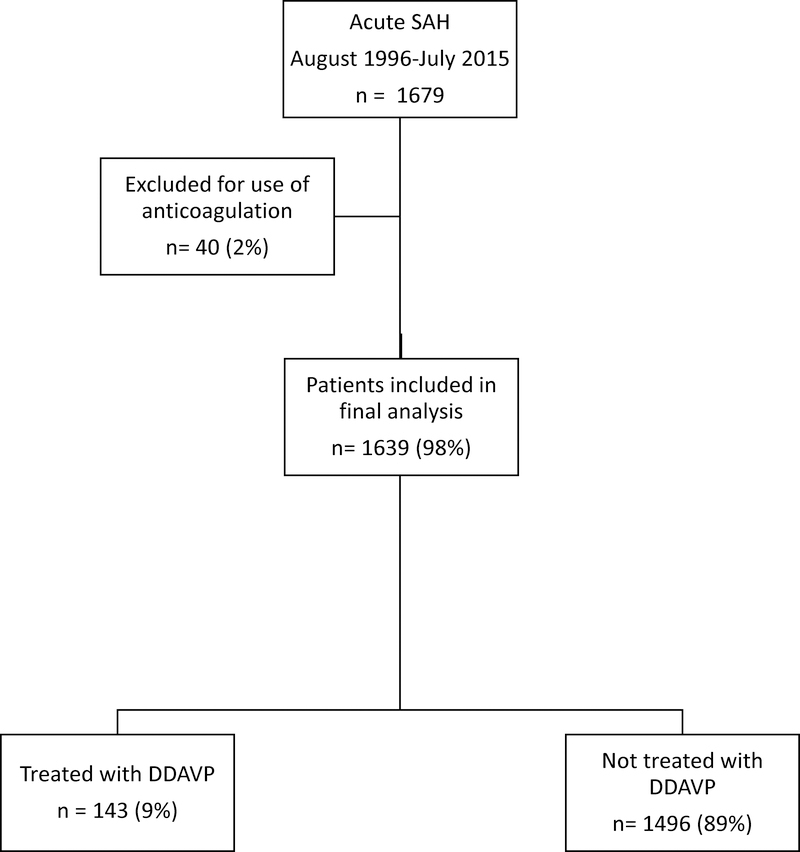

The Columbia University SAH Outcome Project (SHOP) is an ongoing prospective observational database that was established in August 1996. Every adult patient with a spontaneous aneurysmal or non-aneurysmal diagnosis of SAH is offered enrollment. Diagnosis is made by head CT or the presence of red blood cells and xanthochromia on cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Patients with secondary SAH related to trauma, rupture of an arteriovenous malformation or other structural lesions, as well as patients admitted > 14 days after SAH onset, are not included. For the purpose of this study, patients treated with anticoagulant were excluded (Figure 1). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient or a legally authorized representative prior to their inclusion in the study. The study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and therefore was in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

FIG 1.

Flow diagram of patients included in the treatment and control arms of the study.

Clinical Management

All patients were admitted to a dedicated neurocritical care unit and treated per contemporary guidelines. Briefly, they received 60 mg oral nimodipine every 4 hours as well as phenytoin or levetiracetam perioperatively for seizure prophylaxis. Angiography and surgical or endovascular treatment were performed as soon as possible. Aneurysm repair and a one- or two- week trial of critical care is offered to all but the most moribund grade 5 patients (e.g. brainstem failure). An external ventricular drainage shunt was inserted as needed for symptomatic hydrocephalus or intraventricular hemorrhage in patients with a reduced level of consciousness.

Clinical Information

Demographic data, social and medical history and clinical features at onset were obtained by interview with the patient and family members and review of the medical record shortly after admission. Data collected includes medication history, with antiplatelet use being prospectively recorded at admission as well as the use of anticoagulants. Clinical elements of interest at ictus include the occurrence of a sentinel headache, loss of consciousness, and seizures. Seizure was defined as any prehospital tonic-clonic activity based on accounts from eyewitnesses, and loss of consciousness as any alteration in alertness or responsiveness in the prehospital phase. Admission neurological status was evaluated with the Hunt Hess scale[11], administered by an emergency department health care professional or a study neurointensivist. Imaging characteristics including aneurysm size and location, modified Fisher grade and presence of intracerebral hematoma on initial CT were also collected.

Exposure and Outcome Assessment

All instances of DDAVP administration, the exposure of interest, were retrieved through interrogation of the hospital pharmacy database and merged with the SHOP database. DDAVP was given as a single 0.3 μg/kg intravenous dose. Rebleeding, the primary outcome, was defined as either an acute deterioration in neurologic status in conjunction with new hemorrhage apparent on a CT scan or an increase in hemorrhage burden on a repeat CT scan[12]. It was adjudicated in weekly meetings of the study team after review of all relevant clinical and imaging data. Head CT was performed for every episode of neurologic deterioration, defined as a loss of 2 points on the Glasgow Coma Scale. Known potential complications related to treatment with DDAVP, such as hyponatremia (defined as serum sodium < 135 mmol/L), delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) and thrombotic events (myocardial infarct, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism) were also recorded. Finally, a good neurological outcome was defined as a score of 0–3 (independent ambulation or better) on the modified Rankin Scale at 3 months.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression was used to measure the association between treatment with DDAVP and the odds of rebleeding. Univariable and multivariable logistic regressions were employed to investigate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Neurological status at admission, evaluated with the Hunt and Hess scale, and presence of a large aneurysm, defined as > 10mm, have already been demonstrated as predictors of rebleeding in the SHOP database[1], whereas loss of consciousness at onset, seizures before admission, sentinel headache, age, gender, presence of intracerebral hematoma and intraventricular hemorrhage were negative for such an association[13].

Antiplatelet use[6] and more recently, the admission modified Fisher score[14], have also been described as potential risk factors for rebleeding in different cohorts. Therefore, in line with the available literature[15], the following potential confounders were entered in the general model: antiplatelet use, aneurysm size, neurological status and modified Fisher grade. Antiplatelet use, platelet transfusion and aneurysm size (>10 mm) were coded as binary and neurological status (Hunt and Hess scale) and modified Fisher grade were coded as 5-level ordinal categorical variables.

An interaction term was generated between antiplatelet use and DDAVP administration, based on biological plausibility rather than mathematical correlation. The initial model was contracted according to the parsimony principle and highly non-significant variables (p > 0.25) were excluded, including the modified Fisher grade and the interaction term antiplatelet*DDAVP. We felt that antiplatelet use should be kept in the model as a co-variable, even if clearly above significance threshold, as it is unevenly distributed and is clinically relevant regarding DDAVP treatment decisions.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the following alternatives: 1) including only patients with proven aneurysm 2) assuming a missing at random mechanism for incomplete aneurysm size and hence using multiple imputation[16] 3) replacing missing outcome values with worst outcome 4) dichotomization of clinical grade (Hunt-Hess grade IV and V as being poor grades) and 5) including only patients admitted directly to the Columbia University Medical Center (i.e. excluding transfers). All analyses were performed using R version 3.3.1.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 1639 SAH patients were enrolled during the study period, of whom 12% were treated with DDAVP at admission. The intervention group had a worse initial neurological status (higher Hunt and Hess) and higher modified Fisher grade at admission compared to those who were not treated with DDAVP. They were also twice as likely to be using antiplatelet agents compared to the control group (21% vs 11%; p<0.0001). The DDAVP treatment arm had a significantly lower proportion of large aneurysms. Finally, no patient in the control arm received platelets transfusion whereas 44% of patients treated with DDAVP concomitantly received such a therapy (p<0.001). Otherwise, both groups shared similar demographics and clinical characteristics, including proportion of patients exposed to NSAIDs (Table 1). A total of 556 patients were recruited before the adoption in 2008 of DDAVP administration in patients with SAH who were suspected of having received antiplatelet medication. Only 5 of these patients (< 1%) received DDAVP compared with 138 (13%) after 2008. Antiplatelet use was more frequent after 2008 (16% vs 4%), as expected from secular trends on prescription after myocardial infarct[17], stroke or for primary prevention.

Table 1.

Distribution of baseline characteristics according to treatment with DDAVP

| Baseline characteristic | All patients (n=1639) | Patients Treated with DDAVP (n=143) | Control patients (n= 1496) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, y (mean, ±SD) | 55 ±15 | 55 ± 14 | 55 ± 15 | 0.81 |

| Male, n (%) | 538 (33) | 43 (30) | 495 (33) | 0.50 |

| Medical History | ||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 768 (47) | 79 (55) | 689(46) | 0.06 |

| Antiplatelet use, n (%) | 196 (12) | 42 (29) | 154 (10) | <0.001 |

| NSAID use, n (%) | 94 (6) | 18 (13) | 76 (5) | <0.001 |

| Clinical Presentation | ||||

| Sentinel bleed, n (%) | 315 (21) | 34 (27) | 281 (21) | 0.10 |

| Seizures, n (%) | 178 (11) | 16 (12) | 162 (11) | 0.89 |

| LOC, n (%) | 641 (40) | 51 (36) | 590 (40) | 0.39 |

| Hunt and Hess grade, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| I | 384 (24) | 13 (9) | 371 (25) | |

| II | 340 (21) | 44 (31) | 296 (20) | |

| III | 410 (25) | 32 (23) | 378 (25) | |

| IV | 231 (14) | 23 (16) | 208 (14) | |

| V | 269 (16) | 30 (21) | 239 (16) | |

| Imaging | ||||

| Proven aneurysm, n (%) | 1245 (87) | 112 (85) | 1133 (87) | 0.65 |

| Aneurysm >10mm, n (%) | 239 (17) | 11 (8) | 228 (17) | 0.008 |

| Intracerebral Hematoma, n (%) | 275 (17) | 18 (13) | 257 (17) | 0.17 |

| Modified Fisher, n (%) | 0.002 | |||

| 1 | 524 (32) | 47 (24) | 477 (33) | |

| 2 | 197 (12) | 16 (8) | 181 (13) | |

| 3 | 571 (35) | 74 (38) | 497 (35) | |

| 4 | 326 (20) | 57 (29) | 269 (19) | |

| Treatment | ||||

| Platelet transfusion | 87 (5) | 87 (44) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Median time from admission to diagnosis, days (IQR) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

LOC: Loss of consciousness

Missing Data

Data on treatment with DDAVP and on exposure to antiplatelet were complete. Primary outcome information on rebleeding and Hunt and Hess grades at admission were missing for < 1% of patients. However, data on aneurysm size were missing in 23% of patients, mainly in those who died before CT angiography or standard angiography could be performed. Neurological outcome data at 3 months were missing for 206 patients (13%).

Clinical Grade and Aneurysm Size

The final model included the following co-variables: antiplatelet use, presence of a large aneurysm, and neurological status at admission. Presence of a large aneurysm (defined as a maximal diameter of >10mm) was associated with higher odds of rebleeding (adjusted OR 1.61 95% C.I. [ 1.18, 2.17]), as was higher Hunt and Hess grade (that is, a worse neurological status) (adjusted OR 1.97 95% C.I. [1.10, 2.39] per grade). Both these findings are consistent with findings of previous studies.

Association between DDAVP treatment, antiplatelet or NSAID use and rebleeding

The frequency of rebleeding was 9%, representing a total of 143 patients. Treatment with DDAVP (Table 2) was associated with a 45% reduction in the odds of rebleeding (adjusted OR 0.55 95% C.I. [0.27, 0.97]) after adjustment for antiplatelet use, Hunt and Hess grade, and presence of a large aneurysm (Table 3). Contrary to what was expected, antiplatelet use before admission was not significantly associated with higher odds of rebleeding (adjusted OR 1.14 95% C.I. [0.75, 1.68]), nor was use of NSAIDs (adjusted OR 1.07 95% C.I. [0.47, 2.92]). We did not detect any significant interaction between antiplatelet use and DDAVP treatment, meaning that the effect of desmopressin was not limited to those who had received antiplatelet agents; however, our power to detect this effect may have been limited. Finally, platelet transfusion did not reduce the odds of rebleeding (adjusted OR 1.41 95% C.I. [0.24, 8.27]).

Table 2.

Rebleeding incidence in patients treated with DDAVP compared with controls

| Study Arm | Rebleeding n (%) | No Rebleeding n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDAVP | 6 (<1) | 135 (8) | 141 (9) |

| No DDAVP | 137 (8) | 1347 (83) | 1484 (91) |

| Total, n (%) | 143 (9) | 1482 (91) | 1625 (100) |

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted ORs for rebleeding in patients treated with DDAVP compared to controls

| Analysis | OR | 95% C.I. |

|---|---|---|

| Treated with DDAVP (unadjusted) | 0.56 | 0.28 – 0.95 |

| Treated with DDAVP (adjusted for antiplatelet use only) | 0.52 | 0.27 – 0.90 |

| Treated with DDAVP (adjusted for antiplatelet use & HH*) | 0.46 | 0.23 – 0.81 |

| Treated with DDAVP (adjusted for antiplatelet use, HH* and presence of a large aneurysm**) | 0.55 | 0.27 – 0.97 |

HH: Hunt and Hess grade on admission

> 10 mm

Sensitivity Analyses

Worse case scenario analyses concluded to similar association and CIs. Dichotomization of neurological status according to good (Hunt and Hess I-III) and poor (Hunt and Hess grades IV and V) did not have any impact on the association between DDAVP use and rebleeding risk. Analysis restricted to the 1245 patients with a proven aneurysm did not significantly alter the results, although it yielded a wider CI (adjusted OR 0.59 95% C.I. [0.29, 1.04]), as was the case for the analysis restricted to the 296 patients admitted directly to Columbia University Medical Center (adjusted OR 0.32 95% C.I. [0.04, 1.22]). The use of multiple imputation resulted in a much smaller effect size (adjusted OR 0.94 95% C.I. [0.89, 0.98]).

Adverse Effects

As expected, treatment with DDAVP was associated with a higher incidence of hyponatremia (Table 4). However, there was no statistically significant difference in incidence of thrombotic event (pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis or myocardial infarct) or DCI.

Table 4.

Complications associated with DDAVP treatment

| Complication | Patients Treated with DDAVP (n=196) | Control Patients (n= 1443) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyponatremia, n (%) | 30 (21) | 213 (14) | 0.03 |

| Pulmonary embolism, n (%) | 2 (1) | 15 (1) | 0.65 |

| Deep vein thrombosis, n (%) | 12 (9) | 72 (5) | 0.06 |

| Myocardial Infarct, n (%) | 10 (7) | 117 (8) | 0.73 |

| Delayed cerebral ischemia, n (%) | 21 (21) | 135(17) | 0.30 |

Neurological outcome

A total of 290 patients (18%) died during follow up, and good neurological outcome was recorded in 70% of survivors. As expected, rebleeding (OR 4.45 95% C.I. [3.19, 6.43]), poor clinical grade on admission (OR 10.02 95% C.I. [7.67, 13.22]) and presence of a large aneurysm (OR 2.71 95% C.I. [2.00, 3.69]) were all strongly associated with a poor 90-day outcome. After adjustment, treatment with DDAVP was associated with a 47% improvement in odds of good neurological outcome (OR 1.47 95% C.I. [1.06, 2.03]).

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that in patients with SAH, treatment with DDAVP at admission is associated with a significant reduction in odds of rebleeding. To the best of our knowledge, such a finding has not yet been published. If this association represents a real treatment effect, it has the potential to improve patient outcome tremendously. With an expected rate of events of 10%, the number needed to treat would be 16.8 to prevent 1 rebleeding incident.

In our cohort, this association held true after controlling for antiplatelet exposure, suggesting a potential benefit independent of medication-induced platelet dysfunction. It already has been demonstrated that patients with SAH show reduced platelet aggregability and thromboxane release after the index event, which is associated with higher risks of rebleeding[4]. It is plausible that DDAVP reverses, at least partially, these endogenous abnormalities by increasing plasma levels of von Willebrand factor and factor VIII. It suggests that we could consider treatment in all patients with SAH, independently of prior exposure to an antiplatelet.

In the SHOP database, although antiplatelet users were more than 3 times as likely to be treated with DDAVP, most patients that received DDAVP (70%) after 2008 were in fact not antiplatelet or NSAID users. Moreover, among patients with antiplatelet exposure, a significant proportion (60%) did not receive DDAVP. This observation held true in the subgroup of patients admitted directly from the Columbia University Medical Center emergency department, effectively ruling out the possibility of DDAVP administration prior to transfer that could have been missed as a reason for such erratic rates of treatment.

A possible explanation is that given the low risk of the therapy, it was provided on an emergent basis when there was even a remote clinical suspicion of exposure to any antiplatelet, including NSAIDs. Another possibility is a variation in practice among physicians caring for patients with SAH in our center. Interaction between antiplatelet use and DDAVP treatment on the additive scale was not explored since antiplatelet was not significantly associated with rebleeding[18]. However, the power to detect an association between aspirin use and rebleeding within our sample was approximately 20%, possibly due to the shrinking in effect size secondary to treatment with DDAVP.

Another important finding in our cohort is the absence of association between transfusion of platelets and rebleeding, even after adjustment for antiplatelet exposure. Coupled with the recent findings of worse outcome in patients with intracerebral hematoma receiving platelet transfusion[7], this is a strong argument to avoid use of this blood product, which is both costly and associated with multiple complications[19]. The lack of evidence supporting its use is a strong argument to revisit its role in hemostatic optimization in patients with SAH, including for those taking antiplatelet medication.

The strengths of our study include the following. The incidence of rebleeding in our cohort (9%), the prevalence of antiplatelet use (12%), as well as other clinical characteristics were comparable to what has been reported in previous studies. As explained above, the choice of covariables for adjustment was mainly based on prior published work defining risk factors for rebleeding in the same cohort. Aneurysm repair and delay to repair were not included as potential confounders because rebleeding was often a cause for not offering, or for delaying, repair. As such, in many cases, the causal relation was reversed.

Loss to follow-up was minimal, with information on exposure, primary outcome, and all predictors except aneurysm size available for 99% of patients, thereby minimizing selection bias. The prospective nature of data collection also limited information bias. Sensitivity analyses confirmed that the results were robust, and missing data on aneurysm size was handled with multiple imputation according to methodological guidelines from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute[20] (http://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards) and still yielded positive results, although with a weaker association.

Our study also has limitations. The main threat to validity in our observational study is confounding by indication. DDAVP administration was not protocolized or universally applied, and although it was given in higher proportion among antiplatelet users, the latter does not fully account for the decision process underlying its prescription. The potential component of confounding by severity was controlled by including neurological status at admission and aneurysm size in the regression modelling.

As stated above, another possible explanation for the observed inconsistencies is related to divergence of practice amongst treating physicians. Because it was not measured, we were unable to adjust; designs such as matching, or methods such as propensity scoring, would not allow control of this potential residual bias. For example, we would be unable to determine if this could be related to individual preferences or to other factors such as background training (e.g. emergency physician, neurosurgeon, or neurocritical care).

Although using the pharmacy database to retrieve all cases of DDAVP administration offers a near-perfect account of in-hospital treatments, it conveys no information on potential therapies given in another center before transfer. This nondifferential misclassification (underestimation) of DDAVP exposure biases the association towards the null. Moreover, our cohort study includes only patients from a tertiary, reference care center. DDAVP treatment itself is not a standard of care in most centers. Those factors might reduce the generalizability of our findings.

In addition, we lack information on rebleed incidence in patients that were not enrolled in our database. Thus we cannot exclude the possibility that patients with ultra-early rebleeding may have had earlier deaths and did not have a chance to enroll in SHOP. Although our results show a signal towards better neurological outcome in patients treated with DDAVP, the small number of patients in the treatment group does not confer enough power to reach statistical significance and firm conclusions regarding this association. Finally, information on exposure is limited in the sense that we do not have the exact medication or doses that were taken prior to admission, which might have had an association with rebleeding.

CONCLUSION

Rebleeding remains a frequent complication and the most serious threat to favorable outcome after SAH. Its prevention is a crucial component of early patient management. DDAVP is a well-known hemostatic agent with low rates of serious adverse events. Our findings suggest that a single intravenous dose of 0.3 mcg/kg at admission may be associated with a significant reduction in the risk of rebleeding, independent of prior exposure to antiplatelet medication. These findings support further inquiry on the potential role of DDAVP as first-line therapy for emergent medical hemostasis in patients with SAH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Laval University McLaughlin grant (CF) and the NIH K01 ES026833–02 (SP).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Naidech AMJN, Kreiter KT, Ostapkovich ND, Fitzsimmons BF, Parra A, Commichau C, Connolly ES, Mayer SA: Predictors and Impact of Aneurysm Rebleeding After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Arch Neurol 2005, 62:410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lantigua H, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Schmidt JM, Lee K, Badjatia N, Agarwal S, Claassen J, Connolly ES, Mayer SA: Subarachnoid hemorrhage: who dies, and why? Crit Care 2015, 19:309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Germans MR, Coert BA, Vandertop WP, Verbaan D: Time intervals from subarachnoid hemorrhage to rebleed. J Neurol 2014, 261(7):1425–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juvela S, Kaste M: Reduced platelet aggregability and thromboxane release after rebleeding in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of neurosurgery 1991, 74:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujii YTS, Sasaki O, Minakawa T, Koike T, Tanaka R: Ultra-early rebleeding in spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of neurosurgery 1996, 84:35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toussaint LG 3rd, Friedman JA, Wijdicks EF, Piepgras DG, Pichelmann MA, McIver JI, McClelland RL, Nichols DA, Meyer FB, Atkinson JL: Influence of aspirin on outcome following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of neurosurgery 2004, 101(6):921–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baharoglu MI, Cordonnier C, Salman RA-S, de Gans K, Koopman MM, Brand A, Majoie CB, Beenen LF, Marquering HA, Vermeulen M et al. : Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 2016, 387(10038):2605–2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franchini M: The use of desmopressin as a hemostatic agent: a concise review. American journal of hematology 2007, 82(8):731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapapa T, Rohrer S, Struve S, Petscher M, Konig R, Wirtz CR, Woischneck D: Desmopressin acetate in intracranial haemorrhage. Neurol Res Int 2014, 2014:298767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frontera JA, Lewin JJ, Rabinstein AA, Aisiku IP, Alexandrov AW, Cook AM, Del Zoppo GJ, Kumar MA, Peerschke EI, Stiefel MF et al. : Guideline for Reversal of Antithrombotics in Intracranial Hemorrhage : A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the Neurocritical Care Society and Society of Critical Care Medicine. Neurocritical care 2016, 24(1):6–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt WE, Hess RM: Surgical Risk as Related to Time of Intervention in the Repair of Intracranial Aneurysms. Journal of neurosurgery 1968, 28(1):14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LF A.S. Lord, Schmidt JM, Mayer SA, Claassen J, Lee K, Connolly ES, Badjatia N: Effect of rebleeding on the course and incidence of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology 2012, 78:31–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suwatcharangkoon S, Meyers E, Falo C, Schmidt JM, Agarwal S, Claassen J, Mayer SA: Loss of Consciousness at Onset of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage as an Important Marker of Early Brain Injury. JAMA Neurol 2016, 73(1):28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Donkelaar CE, Bakker NA, Veeger NJ, Uyttenboogaart M, Metzemaekers JD, Luijckx GJ, Groen RJ, van Dijk JM: Predictive Factors for Rebleeding After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Rebleeding Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 2015, 46(8):2100–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang C, Zhang TS, Zhou LF: Risk factors for rebleeding of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014, 9(6):e99536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enders C: Analyzing Longitudinal Data With Missing Values. Rehabilitation Psychology 2011, 56(4):267–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Mittleman MA, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC: Improvements in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction and increased use of cardiovascular drugs after discharge: a 10-year trend analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008, 51(13):1247–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL: Concepts of Interaction. In: Modern Epidemiology. Edited by Wilkins LW. Philadelphia; 2008: 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroncek DF, Rebulla P: Transfusion Medicine 2: Platelet transfusions. Lancet 2007, 370:427–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PCORI Methodology Standards. In: PCORI Methodology Standards. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; 2013: A1–A13. [Google Scholar]